Tech “Solutions” Are Pushed By Fossil Fuel Industry To Delay Real Climate Action

This month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world authority on the state of Earth’s climate, released the first installment of its Sixth Assessment Report on global warming. It was signed off by 195 member governments. It spells out, in no uncertain terms, the stakes we are up against — and why we have no time to waste in taking dramatic steps to build a green economy.

The IPCC has been publishing reports on the state of the climate and projections for climate change since 1990. The first IPCC report surmised that human activities were behind global warming, but that further scientific evidence was needed. By the time the Fourth Assessment Report came out in 2007, the evidence for human-caused global warming was described as “unequivocal,” with at least a 9 out of 10 chance of being correct. The report confirmed that the warming of the Earth’s surface to record levels was due to the extra heat being trapped by greenhouse gases and called for immediate action to combat the challenge of global warming.

The Sixth Assessment Report finally states in absolute terms that anthropogenic emissions are responsible for the rising temperatures in the atmosphere, lands and the oceans. In other words, the fossil fuel industry is destroying the planet. And, in a similar tone to some of its previous reports, the IPCC warns that time is running out to combat global warming and avoid its worse effects. Without sharp reduction in emissions, we could easily exceed the 2 degrees Celsius (2°C) temperature threshold by the middle of the century.

Of course, we are already in a climate crisis. Heat waves have broken records this summer in many parts of the world, including the Pacific Northwest of the United States and western Canada; wildfires have ravaged huge areas in southern Europe, causing “disaster without precedent” in Greece, Spain and the Italian island of Sardinia; and deadly floods have upended life in China and Germany. Global average temperatures stand now at 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels. A global warming increase of 1.5°C would have a much greater effect on the probability of extreme weather effects like heat waves, floods, droughts and storms, and at 2°C, things get a lot nastier — and for a much larger percentage of the world’s population.

At current trends, it’s most unlikely that global warming can be held at 1.5°C. We have already emitted enough greenhouse gases into the atmosphere to cause 2°C of warming, according to a group of international scientists who published their findings in Nature Climate Change. Even a 3°C increase or more is plausible. In fact, the Network for Greening the Financial System (a group of central banks and supervisors) is already considering climate scenarios with over 3°C of warming, labeling it the “Hot House World.”

Yet, in spite of all the dire climate warnings by IPCC and scores of other scientific studies, the world’s political and corporate leaders continue with their “business-as-usual” approach when it comes to tackling the climate crisis.

Almost immediately after the release of the new IPCC report, the Biden administration urged the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to increase oil production because higher prices threaten global economic recovery. In fact, Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, actually criticized the world’s major oil producers for not producing enough oil. Naturally, Republicans responded by demanding that the Biden administration should encourage U.S. oil producers to boost production instead of turning to OPEC.

Preposterously, the Biden administration seems to think that the best way to tackle global warming caused by anthropogenic emissions is through increasing levels of combustion of fossil fuels.

This must also be the thinking behind China’s affinity for coal, as the world’s biggest carbon polluter is actually financing more than 70 percent of coal plants built globally.

Or perhaps this is all part of a framework that assumes, “We are doomed, so let’s get it over with quickly.”

In either case, one suspects that political inaction and the prospect of losing the battle against the climate emergency may be the reason why the new IPCC climate report has fully embraced the idea of carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere with the aid of technology as a necessary strategy to contain global warming.

The need for carbon removal was also addressed in the IPCC’s 2018 special report on the 1.5°C temperature limit, both through natural and technological carbon dioxide removal strategies. And an IPCC special report on carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS) dates all the way back to 2005. But it seems that IPCC is now placing greater emphasis than before on innovation and carbon-removal technologies, especially through the process known as direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS).

The actual rationale for the emphasis on a technological fix (geoengineering, by the way, which involves large-scale intervention in and manipulation of the Earth’s natural system, is not included in the IPCC’s latest report) lies in the belief that we can no longer hope to limit global warming to 1.5°C without carbon dioxide removal of greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere, which will then be stored into underground geologic structures or deep under the sea.

Unfortunately, there is a long history of technological promises to address the climate crisis, and the main result is delaying action towards decarbonization and a shift to clean energy, as researchers from Lancaster University have so convincingly argued in a published article in Nature Climate Change.

As things stand, technological solutions to global warming are largely procrastination methods favored by the fossil fuel industry and its political allies. The carbon removal industry is still in its infancy, costs are extremely high, and the methods are unreliable. Nonetheless, both governments and the private sector are investing billions of dollars in the industry and attempts are being made to sell the idea to the public as a necessary step in avoiding a climate catastrophe. A Swiss company called Climeworks is just finishing the completion of a new large-scale direct air capture plant in Iceland, and a similar project is in the works in Norway with hopes that it would actually lead to the creation of “a full-scale carbon capture chain, capable of storing Europe’s emissions permanently under the North Sea.” South Korea is also working on a carbon capture and storage project that may become the biggest in the world.

In the U.S., Republican lawmakers have also been very aggressive in touting carbon capture and storage technologies since the introduction of the Green New Deal legislation by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Edward Markey in 2019.

It all adds up. Relying on technology to attempt to meet climate targets at this stage of the game is meant to obstruct the world from moving away from the use of fossil fuels. If we emphasize those false “fixes,” we are simply quickening the pace of a complete climate collapse with utterly catastrophic consequences for all life on planet Earth.

Our only hope to tackle effectively the climate crisis and save the planet rests not with technological solutions but, instead, with a Green International Economic Order. We need a Global Green New Deal (GGND) to reach net zero emissions by 2050. And this means a world economy without fossil fuels and the industry behind them that is destroying life on the planet.

Decarbonizing the global economy and shifting to clean energy is not an easy task, but it is surely feasible both from a financial and technical standpoint, as numerous studies have shown. According to leading progressive UMass-Amherst economist Robert Pollin, we need to invest between 2.5 to 3 percent of global GDP per year in order to attain a clean energy transformation. Moreover, while 250 years of growth based on the use of fossil fuels have delivered (unequal) economic benefits to the world, a world economy run on clean energy will bring environmental, social and economic benefits. One major study released out of Stanford University shows that a GGND would create nearly 30 million more long-term, full-time jobs than if we remained stuck with what it calls “business-as-usual energy.”

The latest IPCC report, just like previous ones released by the organization, predicts disaster if we do not radically — and immediately — curb carbon dioxide emissions. But we know by now that we cannot rely on our political leaders to do what must be done to save the planet. Nor can we expect technology to solve the climate emergency. Carbon removal and carbon capture technologies won’t solve global warming in time, if ever. Only a roadmap calling for a complete transition away from fossil fuels will save planet Earth.

Pressures from below — led by those on the front lines, labor unions, environmental groups, civil rights movements and students — are our only hope for the necessary changes in the way we produce, deliver and consume energy.

And change is happening. We are moving forward.

Think of how a climate awareness protest by a Swedish teenager turned into a global movement. Or the impact that the Sunrise Movement has had on U.S. politics on account of its activism on the climate crisis within only a few years after it was founded. Or the fact that we have 20 labor unions in California (including two representing thousands of oil workers) endorsing a clean energy transition report produced by a group of progressive economists at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. Or of the great work that the Labor Network for Sustainability is doing in engaging workers and communities in the mission of “building a transition to a society that is ecologically sustainable and economically just.”

The future belongs to the green economy. It can happen. It will happen.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

Chomsky And Pollin: We Can’t Rely On Private Sector For Necessary Climate Action

The new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) climate assessment report, released on August 9, has finally stated in the most absolute terms that anthropogenic emissions are the cause behind global warming, and that we have no time left in the effort to keep temperature from crossing the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold. If we fail to take immediate action, we can easily exceed 2 degrees Celsius by the middle of the century.

Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that while the IPCC report underscores the point that the planet is warming faster than expected, it does not directly mention fossil fuels and puts emphasis on carbon removal as a necessary means to tame global warming even though such technologies are still in their infancy.

In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Noam Chomsky, one of the world’s greatest scholars and leading activists, and Robert Pollin, a world-leading progressive economist, offer their own assessments of the IPCC report. Chomsky and Pollin are co-authors of Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (Verso, 2020).

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, the new IPCC climate assessment report, which deals with the physical science basis of global warming, comes in the midst of extreme heat waves and devastating fires taking place both in the U.S. and in many parts around the world. In many ways, it reinforces what we already know about the climate crisis, so I would like to know your own thoughts about its significance and whether the parties that have “approved” it will take the necessary measures to avoid a climate catastrophe, since we basically have zero years left to do so.

Noam Chomsky: The IPCC report was sobering. Much, as you say, reinforces what we knew, but for me at least, shifts of emphasis were deeply disturbing. That’s particularly true of the section on carbon removal. Instead of giving my own nonexpert reading, I’ll quote the MIT Technology Review, under the heading “The UN climate report pins hopes on carbon removal technologies that barely exist.”

The IPCC report

offered a stark reminder that removing massive amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere will be essential to prevent the gravest dangers of global warming. But it also underscored that the necessary technologies barely exist — and will be tremendously difficult to deploy…. How much hotter it gets, however, will depend on how rapidly we cut emissions and how quickly we scale up ways of sucking carbon dioxide out of the air.

If that’s correct, and I see no reason to doubt it, hopes for a tolerable world depend on technologies that “barely exist — and will be tremendously difficult to deploy.” To confront this awesome challenge is a task for a coordinated international effort, well beyond the scale of John F. Kennedy’s mission to the moon (whatever one thinks of that), and vastly more significant. To leave the task to private power is a likely recipe for disaster, for many reasons, including one brought up by The New York Times report on the idea: “there are risks: The very idea could offer industry an excuse to maintain dangerous habits … some experts warn that they could hide behind the uncertain promise of removing carbon later to avoid cutting emissions deeply today.” The greenwashing that is a constant ruse.

The significance of the IPCC report is beyond reasonable doubt. As to whether the necessary measures will be taken? That’s up to us. We can have no faith in structures of power and what they will do unless pressed hard by an informed public that prefers survival to short-term gain for the “masters of the universe.”

The immediate U.S. government reaction to the IPCC report was hardly encouraging. President Joe Biden sent his national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, to censure the main oil-producing countries (OPEC) for not raising oil production high enough. The message was captured in a headline in the London Financial Times: “Biden to OPEC: Drill, Baby, Drill.”

Biden was sharply criticized by the right wing here for calling on OPEC to destroy life on Earth. MAGA principles demand that U.S. producers should have priority in this worthy endeavor.

Bob, what’s your own take on the IPCC climate assessment report, and do you find anything in it that surprises you?

Robert Pollin: In total, the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report on the physical basis of climate change is 3,949 pages long. So there’s a whole lot to take in, and I can’t claim to have done more than initially review the 42-page “Summary for Policymakers.” Two things stand out from my initial review. These are, first, the IPCC’s conclusion that the climate crisis is rapidly become more severe and, second, that their call for undertaking fundamental action has become increasingly urgent, even relative to their own 2018 report, “Global Warming of 1.50C.” It is important to note that this hasn’t always been the pattern with the IPCC. Thus, in its 2014 Fifth Assessment Report, the IPCC was significantly more sanguine about the state of play relative to its 2007 Fourth Assessment Report. In 2014, they were focused on a goal of stabilizing the global average temperature at 2.0 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, rather than the 1.5 degrees figure. As of 2014, the IPCC had not been convinced that the 1.5 degrees target was imperative for having any reasonable chance of limiting the most severe impacts of climate change in terms of heat extremes, floods, droughts, sea level rises and biodiversity losses. The 2014 report concluded that reducing global CO2 emissions by only 36 percent as of 2050 could possibly be sufficient to move onto a viable stabilization path. In this most recent report, there is no equivocation that hitting the 1.5 degrees target is imperative, and that to have any chance of achieving this goal, global CO2 emissions must be at zero by 2050.

This new report does also make clear just how difficult it will be to hit the zero emissions target, and thus to remain within the 1.5 degrees of warming threshold. But it also recognizes that a viable stabilization path is still possible, if just barely. There is no question as to what the first and most important single action has to be, which is to stop burning oil, coal and natural gas to produce energy. Carbon-removal technologies will likely be needed as part of the overall stabilization program. But we should note here that there are already two carbon-removal technologies that operate quite effectively. These are: 1) to stop destroying forests, since trees absorb CO2; and 2) to supplant corporate industrial practices with organic and regenerative agriculture. Corporate agricultural practices emit CO2 and other greenhouses gases, especially through the heavy use of nitrogen fertilizer, while, through organic and regenerative agriculture, the soil absorbs CO2. That said, if we don’t stop burning fossil fuels to produce energy, then there is simply no chance of moving onto a stabilization path, no matter what else is accomplished in the area of carbon-removal technologies.

I would add here that the main technologies for building a zero-emissions economy — in the areas of energy efficiency and clean renewable energy sources — are already fully available to us. Investing in energy efficiency — through, for example, expanding the supply of electric cars and public transportation systems, and replacing old heating and cooling systems with electric heat pumps — will save money, by definition, for all energy consumers. Moreover, on average, the cost of producing electricity through both solar and wind energy is already, at present, about half that of burning coal combined with carbon capture technology. At this point, it is a matter of undertaking the investments at scale to build the clean energy infrastructure along with providing for a fair transition for the workers and communities who will be negatively impacted by the phase-out of fossil fuels.

The evidence is clear that human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide are behind global warming, and that warming, according to the IPCC report, is taking place faster than predicted. Most likely because of the latter, the Sixth Assessment report provides a detailed regional assessment of climate change, and (for the first time, I believe) includes a chapter on innovation and technology, with emphasis on carbon-removal technologies, which Noam, coincidentally, found “deeply disturbing.” As one of the leading advocates of a Global Green New Deal, do you see a problem if regional climate and energy plans became the main frameworks, at least in the immediate future, for dealing with the climate emergency?

Pollin: In principle, I don’t see anything wrong with regional climate and energy plans, as long as they are all seriously focused on achieving the zero emissions goal and are advanced in coordination with other regions. The big question, therefore, is whether any given regional program is adequate to the requirements for climate stabilization. The answer, thus far, is “no.” We can see this in terms of the climate programs in place for the U.S., the European Union and China. These are the three most important regions in addressing climate change for the simple reason that these three areas are responsible for generating 54 percent of all global CO2 emissions — with China at 30 percent, the U.S. at 15 percent and the EU at 9 percent.

In the U.S., the Biden administration is, of course, a vast improvement relative to the four disastrous years under Trump. Soon after taking office, Biden set out emissions reduction targets in line with the IPCC, i.e., a 50 percent reduction by 2030 and net zero emissions by 2050. Moreover, the American Jobs Plan that Biden introduced in March would have allocated about $130 billion per year in investments that would advance a clean energy infrastructure that would supplant our current fossil fuel-dominant system.

This level of federal funding for climate stabilization would be unprecedented for the U.S. At the same time, it would provide maybe 25 percent of the total funding necessary for achieving the administration’s own emission reduction targets. Most of the other 75 percent would therefore have to come from private investors. Yet it is not realistic that private businesses will mount this level of investment in a clean energy economy — at about $400 billion per year — unless they are forced to by stringent government regulations. One such regulation could be a mandate for electric utilities to reduce CO2 emissions by, say, 5 percent per year, or face criminal liability. The Biden administration has not proposed any such regulations to date. Moreover, with the debates in Congress over the Biden bill ongoing, the odds are long that the amount of federal government funding provided for climate stabilization will even come close to the $130 billion per year that Biden had initially proposed in March.

The story is similar in the EU. In terms of its stated commitments, the European Union is advancing the world’s most ambitious climate stabilization program, what it has termed the European Green Deal. Under the European Green Deal, the region has pledged to reduce emissions by at least 55 percent as of 2030 relative to 1990 levels, a more ambitious target than the 45 percent reduction set by the IPCC. The European Green Deal then aligns with the IPCC’s longer-term target of achieving a net zero economy as of 2050.

Beginning in December 2019, the European Commission has been enacting measures and introducing further proposals to achieve the region’s emission reduction targets. The most recent measure to have been adopted, this past June, is the NextGenerationEU Recovery Plan, through which €600 billion will be allocated toward financing the European Green Deal. In July, the European Commission followed up on this spending commitment by outlining 13 tax and regulatory measures to complement the spending program.

But here’s the simple budgetary math: The €600 billion allocated over seven years through the NextGenerationEU Recovery Plan would amount to an average of about €85 billion per year. This is equal to less than 0.6 percent of EU GDP over this period, when a spending level in the range of 2 to 3 percent of GDP will be needed. As with the U.S., the EU cannot count on mobilizing the remaining 75 percent of funding necessary unless it also enacts stringent regulations on burning fossil fuels. If such regulations are to have teeth, they will mean a sharp increase in what consumers will pay for fossil fuel energy. To prevent all but the wealthy from then experiencing a significant increase in their cost of living, the fossil fuel price increases will have to be matched by rebates. The 2018 Yellow Vest Movement in France emerged precisely in opposition to President Emmanuel Macron’s proposal to enact a carbon tax without including substantial rebates for nonaffluent people.

The Chinese situation is distinct from those in the U.S. and EU. In particular, China has not committed to achieving the IPCC’s emission reduction targets for 2030 or 2050. Rather, as of a September 2020 United Nations General Assembly address by President Xi Jinping, China committed to a less ambitious set of targets: emissions will continue to rise until they peak in 2030 and then begin declining. Xi also committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2060, a decade later than the IPCC’s 2050 target.

We do need to recognize that China has made major advances in support of climate stabilization. As one critical case in point, China’s ambitious industrial policies are primarily responsible for driving down the costs of solar energy worldwide by 80 percent over the past decade. China has also been the leading supplier of credit to support clean energy investments in developing economies. Nevertheless, there is no getting around the fact that if China sticks to its stated emission reduction plans, there is no chance whatsoever of achieving the IPCC’s targets.

In short, for different reasons, China, the U.S. and the EU all need to mount significantly more ambitious regional climate stabilization programs. In particular, these economies need to commit higher levels of public investment to the global clean energy investment project.

The basic constraint with increasing public investment is that people don’t want to pay higher taxes. Rich people can, of course, easily afford to pay higher taxes, after enjoying massive increases in their wealth and income under neoliberalism. That said, it is still also true that most of the funds needed to bring global clean energy investments to scale can be made available without raising taxes, by channeling resources from three sources: 1) transferring funds out of military budgets; 2) converting all fossil fuel subsidies into clean energy subsidies; and 3) mounting large-scale green bond purchasing programs by the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the People’s Bank of China. Such measures can be the foundation for tying together the U.S., EU and Chinese regional programs that could, in combination, have a chance of meeting the urgent requirements for a viable global climate stabilization project.

Noam, I argued recently that we should face the global warming threat as the outbreak of a world war. Is this a fair analogy?

Chomsky: Not quite. A world war would leave survivors, scattered and miserable remnants. Over time, they could reconstruct some form of viable existence. Destruction of the environment is much more serious. There is no return.

Twenty years ago, I wrote a book that opened with biologist Ernst Mayr’s rather plausible argument that we are unlikely to discover intelligence in the universe. To carry his argument further, if higher intelligence ever appears, it will probably find a way to self-destruct, as we seem to be bent on demonstrating.

The book closed with Bertrand Russell’s thoughts on whether there will ever be peace on Earth: “After ages during which the earth produced harmless trilobites and butterflies, evolution progressed to the point at which it has generated Neros, Genghis Khans, and Hitlers. This, however, I believe is a passing nightmare; in time the earth will become again incapable of supporting life, and peace will return.”

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

Average Global Temperature Has Risen Steadily Under 40 Years Of Neoliberalism

Since the advent of neoliberalism 40 years ago, societies virtually all over the world have undergone profound economic, social and political transformations. At its most basic function, neoliberalism represents the rise of a market-dominated world economic regime and the concomitant decline of the social state. Yet, the truth of the matter is that neoliberalism cannot survive without the state, as leading progressive economist Robert Pollin argues in the interview that follows. However, what is unclear is whether neoliberalism represents a new stage of capitalism that engenders new forms of politics, and, equally important, what comes after neoliberalism. Pollin tackles both of these questions in light of the political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, as most governments have implemented a wide range of monetary and fiscal measures in order to address economic hardships and stave off a recession.

Robert Pollin is distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and author of scores of books, including Back to Full Employment (2012), Greening the Global Economy (2015) and Climate Crisis and the Global Green new Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (co-authored with Noam Chomsky, 2020).

C.J. Polychroniou: Neoliberalism is a politico-economic project associated with policies of privatization, deregulation, globalization, free trade, austerity and limited government. Moreover, these principles have reigned supreme in the minds of most policymakers around the world since the early 1980s, and continue to do so. Is neoliberalism a new stage of capitalism?

Robert Pollin: Let’s first be clear on what we mean by “neoliberalism.” The term neoliberalism draws on the classical meaning of the word “liberalism.” Classical liberalism is the political philosophy that embraces the virtues of free-market capitalism and the corresponding minimal role for government interventions. According to classical liberalism, free-market capitalism is the only effective framework for delivering widely shared economic well-being. In this view, only free markets can increase productivity and average living standards while delivering high levels of individual freedom and fair social outcomes. Policy interventions to promote economic equality within capitalism — through, for example, taxing the rich, big government spending on social programs, or regulating market activities through, for example, decent minimum wage standards and regulations to prevent financial markets from becoming gambling casinos — will always end up doing more harm than good, according to this view.

For example, establishing living wage standards as the legal minimum — at, say $15 an hour or higher — would cause unemployment to rise, since, according to classical liberalism, employers won’t be willing to pay unskilled workers more than what the free market determines they are worth. Similarly, regulating financial markets will inhibit capitalists from undertaking risky investments that can raise living standards. Classical liberals will argue that the Wall Street Masters of the Universe are infinitely more qualified than government bureaucrats in deciding what to do with their own money. And if the Wall Street investors make dumb decisions, then so be it; let them fail. In that way, [classical liberalism says] the free market rewards smart decisions and punishes bad ones, all to the greater benefit of the whole society.

Now to neoliberalism: Neoliberalism is a contemporary variant of classical liberalism that became dominant worldwide around 1980, beginning with the elections of Margaret Thatcher in the U.K. and Ronald Reagan in the United States. At that time, it was certainly a new phase of capitalism. Thatcher’s dictum that “there is no alternative” to neoliberalism became a rally cry, supplanting what had been, since the end of World War II, the dominance of Keynesianism and social democracy in global economic policymaking. In the high-income countries of Western Europe and North America along with Japan, in particular, this Keynesian/social democratic version of capitalism featured, to varying degrees, a commitment to low unemployment rates, decent levels of support for working people and workplace conditions, extensive regulations of financial markets, public ownership of significant financial institutions and high levels of public investment.

Of course, this was still capitalism. Disparities of income, wealth and opportunity remained intolerably high, along with the social malignancies of racism, sexism and imperialism. Ecological destruction, in particular global warming, was also beginning to gather force over this period, even though few people took notice at the time. Nevertheless, all told, Keynesianism and social democracy produced dramatically more egalitarian as well as more stable versions of capitalism than the neoliberal regime that supplanted these models.

It is critical to understand that neoliberalism was never a project to replace social democracy with true free-market capitalism. Rather, contemporary neoliberals are committed to free-market policies when they support the interests of big business and the rich as, for example, with lowering regulations in the workplace and financial markets. But these same neoliberals become far less insistent on free market principles when invoking such principles might damage the interests of big business, Wall Street and the rich.

An obvious example is the historically unprecedented levels of support provided during the COVID recession to prevent economic collapse. Just in 2020 in the U.S. for example, the federal government pumped nearly $3 trillion into the economy, equal to about 14 percent of total economic activity (GDP) to prevent a total economic collapse. On top of that, the U.S. Federal Reserve injected nearly $4 trillion — equal to about 20 percent of GDP — to avoid a Wall Street meltdown. Of course, pumping government money into the U.S. economy, at a level equal to roughly one-third of total GDP, all in no more than one year’s time, completely contradicts any notion of free-market, minimal government capitalism.

How would you assess the effects of neoliberal practices on the U.S. economy and society at large?

How neoliberalism works in practice, as opposed to rhetoric, was powerfully illustrated over the past year during the COVID-19 pandemic and recession. That is, due to the public health emergency, employment and overall economic activity throughout the world fell precipitously, since major sections of the global economy were forced into lockdown mode. In the U.S., for example, nearly 50 percent of the entire labor force filed for unemployment benefits between March 2020 and February 2021. However, over this same period, the prices of Wall Street stocks — as measured, for example, by the Standard and Poor’s 500 index, a broad market indicator — rose by 46 percent, one of the sharpest one-year increases on record. Similar interventions throughout the world achieved similar results elsewhere. Thus, according to the International Monetary Fund, overall economic activity (GDP) contracted by 3.5 percent in 2020, which it describes as a “severe collapse … that has had acute adverse impacts on women, youth, the poor, the informally employed and those who work in contact-intensive sectors.” At the same time, global stock markets rose sharply — by 45 percent throughout Europe, 56 percent in China, 58 percent in the U.K. and 80 percent in Japan, and with Standard & Poor’s Global 1200 index rising by 67 percent.

But, of course, these patterns of relentless rising inequality didn’t begin with the COVID recession. Consider, for example, the relationship between corporate CEOs and their workers over the course of neoliberalism. As of 1978, just prior to the rise of neoliberalism, the CEOs of the largest 350 U.S. corporations earned $1.7 million, which was 33 times the $51,200 earned by the average private-sector nonsupervisory worker. As of 2019, the CEOs were earning 366 times more than the average worker, $21.3 million versus $58,200. Under neoliberalism, in other words, the pay for big corporate U.S. CEOs has increased more than tenfold relative to the average U.S. worker.

Of course, there are real lives hovering behind these big statistical patterns. For example, recent research by Anne Case and Angus Deaton has documented powerfully an unprecedented rise, pre-COVID, in what they term “deaths of despair” — i.e., a decline in life expectancy through rising increases in suicide, alcoholism and drug addiction among white working-class people in the U.S. Case and Deaton explain this rise of deaths by despair to the decline in decent-paying and stable working-class jobs that has resulted from neoliberalism. In short, neoliberalism is fundamentally a program of champagne socialism for big corporations, Wall Street and the rich, and “let them eat cake” capitalism for almost everyone else.

Amid our current summer of unprecedented wildfires and flooding, the consequences of global warming are now everywhere before us. But we need to be clear on the extent to which global warming and the rise of neoliberal dominance have been intertwined. Indeed, as of 1980, the year Ronald Reagan took office, the average global temperature was still at a safe level, equal to that of the preindustrial period around 1800. Under 40 years of neoliberalism, the average global temperature has risen relentlessly, to where it is now 1.0 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial average. Climate scientists have insisted that we cannot allow the global average temperature to exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial level. Moreover, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) just released its Sixth Assessment Report, which projects we will be breaching this 1.5-degree threshold by 2040 unless we enact fundamental changes in the way the global economy operates. Step one must be to stop burning oil, coal and natural gas to produce energy. Under neoliberalism, we have allowed fossil fuel companies to continue profiting off of destroying the planet.

Large-scale government interventions are considered an anathema to neoliberal policymakers. Yet, as you and your colleague Jerry Epstein have argued, neoliberalism seems to rely extensively on the state for its own survival. Can you talk a bit about the connection between neoliberalism and government support?

The extraordinary bailout policies that were enacted during the COVID recession were by no means an aberration from what has been standard practice throughout the 40 years that neoliberalism has dominated global economic policymaking.

Indeed, it was only 13 years ago, in 2008, that Wall Street hyper-speculation brought the global economy to its knees during the Great Recession. To prevent a 1930s-level depression at that time, economic policymakers throughout the world — including the United States, the countries of the European Union, Japan, South Korea, China, India and Brazil — all enacted extraordinary measures to counteract the crisis created by Wall Street. As in 2020, these measures included financial bailouts, monetary policies that pushed central bank-controlled interest rates close to near-zero and large-scale fiscal stimulus programs financed by major expansions in central government deficits.

In the United States, the fiscal deficit reached $1.4 trillion in 2009, equal to 9.8 percent of GDP. The deficits were around $1.3 trillion in 2010 and 2011 as well, amounting to close to 9 percent of GDP in both years. These were the largest peacetime deficits prior to the 2020 COVID recession. As with the 2020 crisis, the interventions led by the Federal Reserve to prop up Wall Street and corporate America were even more extensive than the federal government’s deficit spending policies. Moreover, this total figure does not include the full funding mobilized in 2009 to bailing out General Motors, Chrysler, Goldman Sachs and the insurance giant AIG, all of which were facing death spirals at that time. It is hard to envision the form in which U.S. capitalism might have survived at that time if, following true free-market precepts as opposed to the actual practice of neoliberal champagne socialism, these and other iconic U.S. firms would have been permitted to collapse.

Bailout operations of this sort have occurred with near-clockwork regularity throughout the neoliberal era, starting with Ronald Reagan. Thus, in 1983 under Reagan, the U.S. government reached a then peacetime high in the U.S. for federal deficit spending, at 5.7 percent of GDP. At the time, the U.S. and global economy were still mired in the second phase of the severe double-dip recession that lasted from 1980 to ‘82. Reagan was also facing a reelection campaign in 1984. Of course, both as a political candidate and all throughout his presidency, Reagan preached loudly that big government was always the problem, never the solution. Yet Reagan did not hesitate to flout his own rhetoric in overseeing a massive fiscal bailout when he needed it.

If neoliberalism is bad economics and there is a continued need to bailout the current system from recurring crises and disasters, why is it still around after 40 or so years? What keeps it in place? And how likely is it that the return to “emergency Keynesianism” may spell the end of the neoliberal nightmare?

Neoliberalism is not “bad economics” for big corporations, Wall Street and the rich. To the contrary, neoliberalism has been working out extremely well for these groups. The regular massive bailout operations have been neoliberalism’s life-support system. It is due to these bailouts, first and foremost, that neoliberalism remains today as the dominant economic policy framework globally. But it is also true that neoliberalism can be defeated, and supplanted by a policy framework that is committed to high levels of social and economic equality as well as ecological justice — which is to say, a project that has a reasonable chance of protecting human life on earth as we know it. Many people, including myself, like the term “Global Green New Deal” to characterize this project. It’s fine if other people prefer different terms. The point is that this project will obviously require massive and sustained levels of effective political mobilization throughout the world. Whether such mobilizations can be mounted successfully remains the open question moving forward. I myself am inspired by the extent to which the environmental and labor movements, in the U.S. and elsewhere, are increasingly and effectively joining forces to make this happen.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

The Middle East Union Festival I

Berliner Literarischen Aktion

Berliner Literarischen Aktion

Digitale Panels (als Streams) und LIVEMUSIK (vor Ort)

Mit Georges Khalil, Prof. Ella Shohat, Alaa Obeid, Sami Awad Rina Kedem, Maytha Alhassen, Natasha Kermani, Eden Cami und das Kayan Project

Kann und darf man aus dem heutigen Berlin einen friedlich vereinten Nahen Osten imaginieren? Über nationale Grenzen, Kriege, religiöse und sprachliche Unterschiede hinweg? Das Middle East Union Festival der Berliner Literarischen Aktion lässt mit Literatur, Diskurs und Musik diese Vision zum Greifen nah erscheinen. Das von Hila Amit und Mati Shemoelof kuratierte Festival gastiert im Kino Babylon (12.8.), der NoVilla (15.8.) und an zwei Tagen mit digitalen Panels und einem abendlichem Liveprogramm im LCB.

Arabisch-jüdisches Schreiben: Überlegungen zu Verdrängung und nahöstlicher Diaspora

Mit Georges Khalil und Prof. Ella Shohat digital (engl.)

https://lcb.de/programm/the-middle-east-union-festival-i/

Das gesamte Festivalprogramm auf www.middle-east-union.de

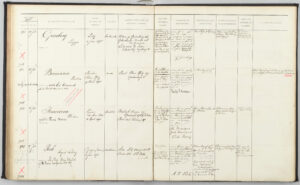

Félix Fénéon, kunstcriticus en anarchist

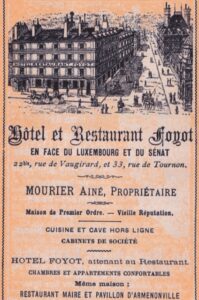

Dat de Franse dichter Laurent Tailhade behalve zijn avondmaaltijd een oog moest missen, was een meer dan sneu gevolg van de bomaanslag die kunstkenner en –criticus Félix Fénéon op 4 april 1894 pleegde op het restaurant van Hôtel Foyot aan de Rue de Tournon in Parijs.

Het was vooral sneu omdat Tailhade Fénéon persoonlijk kende en ook diens anarchistische opvattingen deelde. Zijn verwondingen weerhielden Tailhade er echter niet van in de jaren daarna in zijn werk het anarchisme volop uit te dragen.

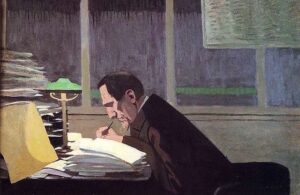

Ministerie

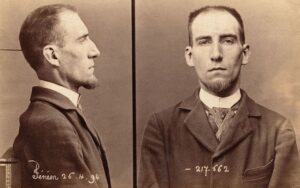

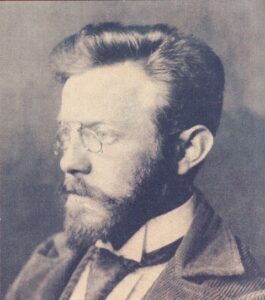

Félix Fénéon (1861-1944) groeide op in de Bourgogne maar vertrok al snel naar Parijs. Op zijn twintigste kreeg hij een baan als klerk op het Ministerie van Oorlog. Hij zou er dertien jaar blijven werken. Daarnaast redigeerde hij voor uitgeverijen werk van Arthur Rimbaud en Lautréamont. Met zijn dandyachtige voorkomen – puntbaard, wandelstok, zwarte cape – was hij in kunstkringen een opvallende verschijning. Wekelijks bezocht hij de populaire kunstsalon van Stéphane Mallarmé. Naast zijn baan op het ministerie werd hij kunstcriticus bij het tijdschrift La Libre Revue. Ook schreef hij gezaghebbende artikelen over kunst en literatuur voor bladen als La Vogue en La Revue wagnérienne. Hij was de ontdekker van de schilder Georges Seurat en was bevriend met de schilder Paul Signac, die hem op een schilderij vereeuwigde. Ook de kunstenaars Toulouse-Lautrec en Félix Valleton maakte portretten van Fénéon. Hij was een onvermoeibaar promotor van het werk Seurat en Signac, die beiden gezien worden als de wegbereiders van het pointillisme. Voor deze stijl en andere daaraan gelieerde kunststromingen bedacht Fénéon de term neonimpressionisme.

Anarchisten

Fénéon kreeg eveneens contacten in anarchistische kringen en hij ging schrijven voor het toonaangevende anarchistische tijdschrift L’En-Dehors van de anarchist Zo d’Axa en voor Revue anarchiste. Toen Zo d’Axa zijn toevlucht zocht in Londen nam Fénéon de redactie van L’En-Dehors over. Aan het tijdschrift werd onder meer meegewerkt door Octave Mirbeau. Jean Grave, Sébastien Faure, Bernard Lazare, Tristan Bernard en de Belgische anarchist Émile Verhaeren. Hij raakte bevriend met de Nederlandse anarchist Alexander Cohen en met ‘anarchist van de daad’ Émile Henry, die later de beruchte bomaanslag op het Café Terminus zou plegen. Soms logeerde Henry bij Fénéon of bij Cohen thuis. Al eerder had Fénéon Henry al eens aan een jurk geholpen, om in vermomming de politie te kunnen ontlopen.

Aanslagen

De uit Leeuwarden afkomstige Cohen (1864-1961) was na een redacteurschap bij Recht voor Allen van Domela Nieuwenhuis overhaast naar Parijs verhuisd. In Nederland werd hij gezocht wegens majesteitsschennis. Tijdens een rijtour van Koning Willem III had hij geroepen: ‘Leve Domela Nieuwenhuis! Leve het socialisme! Weg met Gorilla!’.

In Parijs ging hij schrijven voor de anarchistische bladen L’En-Dehors en Le Père peinard en werd hij correspondent voor Recht voor Allen. In de Franse hoofdstad werden Fénéon en Émile Henry zijn beste vrienden.

Henry wilde in 1892 de eisen van stakende mijnarbeiders bij de Carmoux mijnmaatschappij kracht bijzetten en plaatste een bom bij het kantoor van de maatschappij in Parijs. De bom werd echter ontdekt en meegenomen naar een politiebureau in de Rue des Bons-enfants. Daar ontplofte de bom alsnog waarbij vijf politiemannen om het leven kwamen.

Zijn volgende aanslag was een wraakneming voor de executie van de anarchist Auguste Vailllant, ter dood veroordeeld wegens het plegen van een bomaanslag op de Chambre des Députés, de Kamer der Afgevaardigen. Op 12 februari 1894 plaatste Henry een bom onder een tafeltje in het drukbezochte Café Terminus bij het Gare St. Lazare. Eén persoon kwam om het leven en twintig mensen raakten gewond. Henry werd gearresteerd en in mei 1894 terechtgesteld.

Restaurant

Restaurant

Fénéon, die vond dat zijn eigen schriftelijke bijdragen aan het verkondigen van de anarchistische boodschap niet voldoende effect hadden, nam zich voor de vertegenwoordigers van de bourgeoisie in het hart te treffen. Op 4 april 1894 verstopte hij een bom in een bloempot en toog ermee naar de zetel van de Franse senaat, gevestigd in het paleis in de Jardin du Luxembourg. Daar bleek hij echter niet in de buurt van het bewaakte gebouw te kunnen komen, waarop hij besloot de bom te plaatsen bij het tegenover gelegen Hôtel Foyot, een door veel parlementariërs bezochte eetgelegenheid. Hij plaatste de bloempot in de vensterbank van het restaurant, stak de lont aan en wandelde rustig naar de Place de l’Odéon, waar hij op de bus richting Clichy sprong. Door de ontploffing sneuvelden ramen en stortten kroonluchters van het plafond omlaag. Alleen de dichter Tailharde raakte gewond, het kostte hem een oog.

Huiszoeking

Vanwege zijn anarchistische activiteiten werd Fénéon al enige tijd door de politie in de gaten gehouden. Een dag na de aanslag doorzocht de politie zijn woning maar kon daar geen verdachte aanwijzingen ontdekken. De huiszoeking moest wel op een misverstand berusten, concludeerde de politie-inspecteur en bood excuses aan. Op het politiebureau ondertekende Fénéon een verklaring waarin hij ontkende aanhanger van het anarchisme te zijn, en vertrok naar zijn kantoor op het Ministerie van Oorlog. Daar bewaarde hij in een la van zijn bureau een fles kwikzilver en enige ontstekers – hem door Henry in bruikleen gegeven – die echter door de politie werden ontdekt. Dit en zijn anarchistische activiteiten waren voldoende om hem te arresteren. Met de aanslag op het Hôtel Foyot is hij echter nooit meer in verband gebracht.

Proces

Proces

De Franse regering was de aanslagen beu en vaardige een serie strenge wetten uit waarbij iedere anarchistische activiteit strafbaar werd gesteld. Dertig vooraanstaande anarchisten werd ‘organisatie van criminele activiteiten’ ten laste gelegd, onder wie Sébastien Faure, Jean Grave, Paul Reclus, Félix Fénéon en Alexander Cohen. Voor de Franse staat draaide dit ‘Procès des trente’ echter uit op een mislukking. Slechts acht beklaagden werden veroordeeld, vier van hen bij verstek, onder wie Reclus en Alexander Cohen. De laatste had inmiddels de wijk naar Londen genomen. Pas in 1899 zou hij naar Parijs terugkeren.

Tijdens het proces wist Fénéon op vaak humoristische wijze aanklachten tegen hem te pareren. Bij een beschuldiging van een ‘nauw contact’ met de Duitse anarchist Kampfmeyer, antwoordde hij: ‘Ik spreek geen Duits en Kampfmeyer spreekt geen Frans. Hoe nauw moet dat contact dan geweest zijn?’ En toen hij beticht werd een vooraanstaande anarchist te hebben gesproken ‘achter een gaslantaarn’, was zijn antwoord: ‘Neem me niet kwalijk, Monsieur le Préfect, maar wat is de achterkant van een gaslantaarn?’ Fénéon werd vrijgesproken maar zijn baan op het ministerie moest hij wel opgeven.

Drie regels

Als redacteur kon hij aan de slag bij het vooraanstaande kunsttijdschrift La Revue Blanche. Ook daarin vestigde hij voortdurend de aandacht op het werk van Seurat en Signac en in 1900 organiseerde hij de eerste overzichtstentoonstelling van schilderijen van Seurat. In het tijdschrift publiceerde hij ook werk van Marcel Proust, Appolinaire, Paul Claudel en vertaalde hij Jane Austen en brieven van Edgar Allen Poe.

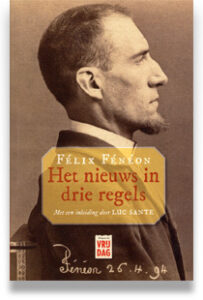

In 1906 ging hij voor de krant Le Matin de dagelijkse pagina faits divers samenstellen: berichten uit stad en provincie, die –zo was de opdracht – in de krant niet langer dan drie regels mochten zijn. Nieuwtjes over inbraken, ongelukken, crimes passionnel, moorden, branden en ander leed, werden door Fénéon geminimaliseerd tot gevatte beschrijvingen van het gebeurde, vaak met een kwinkslag of woordspeling, soms met kort commentaar. Hij puzzelde met woorden, zoals een dichter of liedjesschrijver. Ieder bericht vormt een verhaal op zich en roept vragen op over het hoe en waarom. Intrigerende, vermakelijke of hilarische, tragische of ontroerende berichten die in veel gevallen de aanzet tot een roman zouden kunnen zijn. De berichten zijn te vergelijken met de collages die Picasso en Braque jaren later uit gescheurde kranten samenstelden, maar doen ook denken aan de collages van Kurt Schwitters en aan de wijze waarop William Burroughs in de jaren vijftig kranten verknipte en omsmeed tot een roman. Dankzij het knipwerk van Fénéons vriendin zijn twaalfhonderd stukjes bewaard gebleven en in 2009 in boekvorm verschenen. Fénéon schreef de stukjes om in zijn onderhoud te voorzien, maar wellicht vond hij ook voldoening bij het in kaart brengen van het verval in de Franse samenleving. De lezer kon zelf zijn conclusie trekken.

In 1906 ging hij voor de krant Le Matin de dagelijkse pagina faits divers samenstellen: berichten uit stad en provincie, die –zo was de opdracht – in de krant niet langer dan drie regels mochten zijn. Nieuwtjes over inbraken, ongelukken, crimes passionnel, moorden, branden en ander leed, werden door Fénéon geminimaliseerd tot gevatte beschrijvingen van het gebeurde, vaak met een kwinkslag of woordspeling, soms met kort commentaar. Hij puzzelde met woorden, zoals een dichter of liedjesschrijver. Ieder bericht vormt een verhaal op zich en roept vragen op over het hoe en waarom. Intrigerende, vermakelijke of hilarische, tragische of ontroerende berichten die in veel gevallen de aanzet tot een roman zouden kunnen zijn. De berichten zijn te vergelijken met de collages die Picasso en Braque jaren later uit gescheurde kranten samenstelden, maar doen ook denken aan de collages van Kurt Schwitters en aan de wijze waarop William Burroughs in de jaren vijftig kranten verknipte en omsmeed tot een roman. Dankzij het knipwerk van Fénéons vriendin zijn twaalfhonderd stukjes bewaard gebleven en in 2009 in boekvorm verschenen. Fénéon schreef de stukjes om in zijn onderhoud te voorzien, maar wellicht vond hij ook voldoening bij het in kaart brengen van het verval in de Franse samenleving. De lezer kon zelf zijn conclusie trekken.

In Rouen heeft M. Colombe zich gisteren met één kogel gedood. In maart had zijn vrouw hem er drie in het lijf geschoten en de echtscheiding was op handen.

Met haar tachtig jaren werd Mme Saout uit Lambézellec stilaan bang dat de dood haar zou overslaan. Toen haar dochter even de deur uit was, knoopte zij zich op.

In Falaise verwelkomde oud-burgemeester M. Ozanne de deurwaarder Vieillot met geweerschoten om zich, na één treffer, het leven te benemen.

Jacquot, eerste bediende bij een kruidenier in Les Maillys, heeft zich en zijn vrouw om het leven gebracht. Hij was ziek, zij niet.

Zittend in de vensterbank van het open raam, reeg G. Laniel, negen, uit Meaux haar laarsjes dicht. Bijna. Tot zij achterover op de keien smakte.

(uit: Félix Fénéon, Het nieuws in drie regels, Antwerpen 2009)

Geruchten

Jarenlang deden nog geruchten de ronde dat de aanslag bij Hôtel Foyot het werk van Fénéon was geweest. Fénéon zelf heeft er nooit in het openbaar over gesproken en besteedde er geen aandacht aan. Slechts eenmaal bevestigde hij dat hij de dader was, in een gesprek met Kaya Batut, de vrouw van Alexander Cohen.

Noot

1. Vorig jaar werd in het Moma in New York een grote tentoonstelling aan Fénéon gewijd, waarop onder meer werk van Seurat en Signac te zien was.

Literatuur

Alexander Cohen, In opstand, Amsterdam 1932

John Merriman, The Dynamite Club, New Haven/London 2009

Félix Fénéon, Het nieuws in drie regels, Antwerpen 2009

Joan Ungersma Halperin, Félix Fénéon, Aesthete & Anarchist in Fin-de-Siècle Paris, New Haven/London 1988