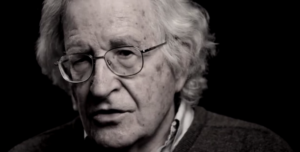

Noam Chomsky

Irrational political panic is as American a phenomenon as apple pie. It often arises as a result of a potential inability on the part of the powers-that-be to control the outcome of developments that may pose challenges to the interests of the existing socioeconomic order or to the status quo of the geostrategic environment. The era of the Cold War speaks volumes about this phenomenon, but it’s also evident in earlier periods — for example, the first Red Scare in the wake of World War I — and we can see clear parallels in the present-day situation with reactions to Ukraine and the rise of China as a global power.

In the interview that follows, world-renowned public intellectual Noam Chomsky delves into the phenomenon of irrational political panics in the U.S., with an emphasis on current developments on the foreign policy front — and the dangers of seeking to maintain global hegemony in a multipolar world.

C.J. Polychroniou: The political culture in the United States seems to have a propensity toward alarmism when it comes to political developments that are not in tune with the economic interests, ideological mindset and strategic interests of the powers-that-be. Indeed, from the anti-Spanish panic of the late 1890s to today’s rage about Russia’s security concerns over Ukraine, and China’s growing role in world affairs and everything in between, the political establishment and the media of this country tend to respond with full-blown alarm to developments that are not in alignment with U.S. interests, values and goals. Can you comment about this peculiar state of affairs, with particular emphasis on what’s happening today in connection with Ukraine and China?

Noam Chomsky: Quite true. Sometimes it’s hard to believe. One of the most significant and revealing examples is the rhetorical framework of the major internal planning document of the early Cold War years, NSC-68 of 1950, shortly after “the loss of China,” which set off a frenzy in the U.S. The document set the stage for huge expansion of the military budget. It’s worth recalling today when strains of this madness are reverberating — not for the first time; it’s perennial.

The policy recommendations of NSC-68 have been widely discussed in scholarship, though avoiding the hysterical rhetoric. It reads like a fairytale: ultimate evil confronted by absolute purity and noble idealism. On one side is the “slave state” with its “fundamental design” and inherent “compulsion” to gain “absolute authority over the rest of the world,” destroying all governments and the “structure of society” everywhere. Its ultimate evil contrasts with our sheer perfection. The “fundamental purpose” of the United States is to assure “the dignity and worth of the individual” everywhere. Its leaders are animated by “generous and constructive impulses, and the absence of covetousness in our international relations,” which is particularly evident in the traditional domains of U.S. influence, the Western hemisphere, long the beneficiary of Washington’s tender solicitude as its inhabitants can testify.

Anyone familiar with history and the actual balance of global power at the time would have reacted to this performance with utter bewilderment. Its State Department authors couldn’t have believed what they were writing. Some later gave an indication of what they were up to. Secretary of State Dean Acheson explained in his memoirs that in order to ram through the huge planned military expansion, it was necessary to “bludgeon the mass mind of ‘top government’” in ways that were “clearer than truth.” The highly influential Sen. Arthur Vandenberg surely understood this as well when advising [in 1947] that the government must “scare the hell out of the American people” to rouse them from their pacifist backwardness.

There are many precedents, and the drums are beating right now with warnings about American complacency and naivete about the intentions of the “mad dog” Putin to destroy democracy everywhere and subdue the world to his will, now in alliance with the other “Great Satan,” Xi Jinping.

The February 4 Putin-Xi summit, timed with the opening of the Olympic games, was recognized to be a major event in world affairs. Its review in a major article in The New York Times is headlined “A New Axis,” the allusion unconcealed. The review reported the intentions of the reincarnation of the Axis powers: “The message that China and Russia have sent to other countries is clear,” David Leonhardt writes. “They will not pressure other governments to respect human rights or hold elections.” And to Washington’s dismay, the Axis is attracting two countries from “the American camp,” Egypt and Saudi Arabia, stellar examples of how the U.S. respects human rights and elections in its camp — by providing a massive flow of weapons to these brutal dictatorships and directly participating in their crimes. The New Axis also maintains that “a powerful country should be able to impose its will within its declared sphere of influence. The country should even be able to topple a weaker nearby government without the world interfering” — an idea that the U.S. has always abhorred, as the historical record reveals.

Twenty-five hundred years ago, the Delphi Oracle issued a maxim: “Know Thyself.” Worth remembering, perhaps.

As in the case of NSC-68, there is method in the madness. China and Russia do pose real threats. The global hegemon does not take them lightly. There are some striking common features in how U.S. opinion and policy are reacting to the threats. They merit some thought.

The Atlantic Council describes the formation of the New Axis as a “tectonic shift in global relations” with plans that are truly “head spinning”: “The sides agreed to more closely link their economies through cooperation between China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Putin’s Eurasian Economic Union. They will work together to develop the Arctic. They’ll deepen coordination in multilateral institutions and to battle climate change.”

We should not underestimate the grand significance of the Ukraine crisis, adds Damon Wilson, president of the National Endowment for Democracy. “The stakes of today’s crisis are not about Ukraine alone, but about the future of freedom,” no less.

Strong measures have to be taken right away, says Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell: “President Biden should use every tool in his tool box and impose tough sanctions ahead of any invasion and not after it happens.” There is no time to dilly-dally with Macron-style appeals to the raging bear to temper his violence.

Received doctrine is that we must confront the formidable threat of China and stand firm on Ukraine, while Europe wavers and Ukraine asks us to tone down the rhetoric and pursue diplomatic measures. Luckily for the world, Washington is unflinching in its dedication to what is right and just, even if it is almost alone, as when it righteously invades Iraq and strangles Cuba in defiance of virtually uniform international protest, to take just two from a plethora of examples.

To be fair, adherence to the doctrine is not uniform. There’s deviation, most forcefully on the far right: Tucker Carlson, probably the most influential TV voice. He’s said we shouldn’t be involved in defending Ukraine against Russia — because we should be devoting all our resources to confronting the far more awesome China threat. Have to get our priorities straight in combating the Axis.

Warnings about Russia’s mobilization to invade Ukraine have been an annual media event since the crises of 2014, with regular reports of tens or hundreds of thousands of Russian troops preparing to attack. Today, however, the warnings are far more shrill, with a mixture of fear and ridicule for so-called Mad Vlad, whom the New York Times’s Thomas Friedman describes as a “one-man psychodrama, with a giant inferiority complex toward America that leaves him always stalking the world with a chip on his shoulder so big it’s amazing he can fit through any door,” or from another perspective, the Russian leader seeking in vain for some response to his repeated requests for some attention to Russia’s expressed concerns. An analysis by MintPress found that 90 percent of the opinion pieces in the three major national newspapers have adopted a hawkish militant stance, with a bare scattering of questioning — a familiar phenomenon, as in the days before the Iraq invasion and, in fact, routinely when the state has delivered the word.

As in the case of the Sino-Soviet conspiracy to gain “absolute authority over the rest of the world” in 1950, the word now is that the U.S. must act decisively to counter the threat of the New Axis to the “rule-based global order” that is hailed by U.S. commentators, an interesting concept to which I’ll return briefly.

The “tectonic shift” is not a myth, and it does pose a threat to the U.S. It threatens U.S. primacy in shaping world order. That’s true of both of the crisis areas, on the borders of Russia and of China. In both cases, negotiated settlements are within reach: regional settlements. If they are achieved, the U.S. will only have an ancillary role, which it may not be willing to accept even at the cost of inflaming extremely hazardous confrontations.

In Ukraine, the basic outlines of a settlement are well-known on all sides; we’ve discussed them before. To repeat, the optimal outcome for security of Ukraine (and the world) is the kind of Austrian/Nordic neutrality that prevailed through the Cold War years, offering the opportunity to be part of Western Europe to whatever extent they chose, in every respect apart from providing the U.S. with military bases, which would have been a threat to them as well as to Russia. For internal Ukrainian conflicts, Minsk II provides a general framework.

As many analysts observe, Ukraine is not going to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in the foreseeable future. George W. Bush rashly issued an invitation to join, but it was immediately vetoed by France and Germany. Though it remains on the table under U.S. pressure, it is not an option. All sides recognize this. The astute and knowledgeable Central Asia scholar Anatol Lieven comments that “the whole issue of Ukraine’s NATO membership is in fact purely theoretical, so that, in some respects, this whole argument is an argument about nothing — on both sides, it must be said, Russian as well as the West.”

His comment brings to mind [Argentinian writer Jorge Luis] Borges’s description of the Falkland/Malvinas war: two bald men fighting over a comb.

Russia pleads security concerns. For the U.S., it is a matter of high principle: We cannot infringe on the sacred right of sovereignty of nations, hence the right to join NATO, which Washington knows is not going to happen.

On the Russian side, a formal pledge of non-alignment hardly increases Russian security, any more than Russian security was enhanced when Washington guaranteed to Gorbachev that “not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction,” soon abrogated by Clinton, then more radically by W. Bush. Nothing would have changed if the promise had risen from a gentlemen’s agreement to a signed document.

The U.S. plea hardly rises to the level of comedy. The U.S. has utter disdain for the principle it proudly proclaims, as recent history once again dramatically confirms.

For Washington, there is a deeper issue: A regional settlement would be a serious threat to the U.S. global role. That concern has been simmering right through the Cold War years. Will Europe assume an independent role in world affairs, as it surely can, perhaps along Gaullist lines: Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals, revived in Gorbachev’s 1989 advocacy of a “common European home,” a “vast economic space from the Atlantic to the Urals”? Even more unthinkable would be Gorbachev’s broader vision of a Eurasian security system from Lisbon to Vladivostok with no military blocs, shot down without discussion in the negotiations 30 years ago over a post-Cold War settlement.

The commitment to maintain the Atlanticist order in Europe, in which the U.S. reigns supreme, has had policy implications that reach beyond Europe itself. One crucial example was Chile in 1973, when the U.S. was working hard to overthrow the parliamentary government, finally succeeding with the installation of the murderous Pinochet dictatorship. A prime reason for destroying democracy in Chile was explained by its prime architect, Henry Kissinger. He warned that parliamentary social reforms in Chile might provide a model for similar efforts in Italy and Spain that might lead Europe on an independent path, away from subordination to U.S. control and the U.S. model of harsher capitalism. The domino theory, often derided, never abandoned, because it is an important instrument of statecraft. The issue arises again with regard to a regional settlement of the Ukraine conflict.

Much the same is true in the confrontation with China. As we’ve discussed earlier, there are serious issues concerning China’s violation of international law in the neighboring seas — though as the one maritime country that refuses even to ratify the UN Law of the Sea, the U.S. is hardly in a strong position to object. Nor does the U.S. alleviate these problems by sending a naval armada through these waters or providing Australia with a fleet of nuclear submarines to enhance the already overwhelming military superiority of the U.S. off the coasts of China. The issues can and should be addressed by the regional powers.

As in the case of Ukraine, however, there is a downside: The U.S. will not be in charge.

Also as in the case of Ukraine, the U.S. professes its commitment to high principle in taking the lead to confront the threat of China: its horror at China’s human rights abuses, which are doubtless severe. Again, it is easy enough to assess the sincerity of this stand. One revealing index is U.S. military aid. At the top, in a category by themselves, are Israel and Egypt. On the Israeli record on human rights, we can now refer to the detailed reports of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, reviewing the crimes of what they describe as the world’s second apartheid state. Egypt is suffering under the harshest dictatorship of its tortured history. More generally, for many years, there has been a striking correlation between U.S. military aid and torture, massacre, and other severe human rights abuses.

There is no more need to tarry on Washington’s concern for human rights than on its dedication to the sacred principle of sovereignty. The fact that these absurdities can even be discussed illustrates how deeply the rhetorical flights of NSC-68 permeate the intellectual culture.

Hebrew University lecturer Guy Laron usefully reminds us of another facet of the Ukraine crisis: the long struggle between the U.S. and Russia over control of Europe’s energy, again in the headlines today. Even before Russia was a player, the U.S. sought to shift Europe (and Japan) to an oil-based economy, where the U.S. would have the hand on the spigot. Much of Marshall Plan aid was directed to this end. From George Kennan to Zbigniew Brzezinski commenting on the invasion of Iraq (which he opposed, but felt might confer advantages to the U.S. with the anticipated control over major oil resources), planners have recognized that control over energy resources could provide “critical leverage” over allies. Later years saw many struggles in the Cold War framework Laron describes, now very prominent. Ukraine has had a large part in these confrontations.

Throughout, the shape of world order has of course been a driving concern of policy makers. For post-World War II Washington, there is only one acceptable form: under its leadership. And it must be a particular form of world order: the “rule-based international order,” which has displaced an earlier commitment to the “UN-based international order” established under U.S. lead after World War II. It’s not hard to discern the reasons for the transition in policy and accompanying commentary. In the rule-based order, the U.S. sets the rules.

The same was true in the UN-based order in the early years after World War II. U.S. global dominance was so overwhelming that the UN served virtually as a tool of U.S. foreign policy and a weapon against its enemies. Not surprisingly, the UN was highly regarded in U.S. popular and intellectual culture, along with the UN-based international order, guided by Washington.

That turned out to be a passing phase. The UN began to fall out of favor in U.S. elite opinion as it lurched out of control with the recovery of other industrial societies but particularly with decolonization, which brought discordant voices into the UN and also in independent structures such as the Non-Aligned Movement and many others — all very vocal and active, though effectively barred from the international information order dominated by the traditional imperial societies.

Within the UN there were calls for a “New International Economic Order” that would offer the Global South something better than a continuation of the large-scale robbery, violent intervention and subversion that the colonized world had enjoyed during the long reign of Western imperialism. There were other threats, such as a call for a New International Information Order that would provide some opportunity for voices of the former colonies to enter the international information system, a near monopoly of the imperial powers.

The masters of the world undertook vigorous campaigns to beat back these efforts, a major though largely ignored chapter of modern history — though not completely; there is some fine work of exposure and analysis.

One effect of the Global South’s disruptive efforts was to turn U.S. practice and elite opinion against the UN, no longer a reliable agency of U.S. power as it had been in the early Cold War years. Furthermore, the foundations of modern international law in the few UN treaties that the U.S. ratified became completely unacceptable as the years passed, particularly the banning of “the threat or use of force” in international affairs, a practice in which the U.S. is far in the lead. It is conventional to say that the U.S. and Russia engaged in proxy wars during the Cold War years — omitting the fact that with rare exceptions, these were conflicts in which Russia provided some support to victims of U.S. attack. All topics that should have far more prominence.

In this context, the “rule-based international order” became the favored pillar of world order, and there is much annoyance when China calls instead for the UN-based international order as it did at the rancorous March 2021 China-U.S. summit in Alaska (putting aside the sincerity of these pronouncements).

It’s intriguing to see how the conflict with China plays out in U.S. policy and discourse in other domains. A front-page story in The New York Times is headlined: “House Passes Bill Adding Billions to Research to Compete With China; The vote sets up a fight with the Senate, which has different recommendations for how the United States should bolster its technology industry to take on China.” The official name of the bill is “The America Competes Act of 2022” — meaning “compete” with China.

The passage of the bill was hailed in the left-liberal press: “The House gave President Joe Biden another reason to celebrate on Friday with the passage of a bill aimed at boosting competitiveness with China.”

Could Congress support research and development because it would help American society, as this bill surely would? Apparently not; only because it would “take on China.” Republicans reflexively opposed the bill as usual, in this case because it “concedes too much to China.” Republicans also opposed what they called “far left” initiatives such as addressing climate change. The bill was derided by House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy as the “coral reefs bill.” How does saving humanity from self-destruction help to compete with China?

A side comment: An amendment to the bill was introduced by Pramila Jayapal, chair of the Progressive Caucus, a call to release the near-$10 billion of the Afghan government held in New York banks, so as to help relieve the horrendous humanitarian crisis facing the population. It was voted down. Forty-four Democrats joined Republican brutality. It appears that the China-based Shanghai Cooperation Organization might be planning aid, more of the China threat.

There is no denying that China is a rising superpower confronting the U.S. Reporting a study of Harvard’s Belfer Center of International Affairs, Graham Allison argued further that the so-called Thucydides Trap is likely to lead to a U.S.-China war.

That cannot happen. U.S.-China war means simply: game over. There are critical global issues on which the U.S. and China must cooperate. They will either work together, or collapse together, bringing the world down with them.

One of the most striking developments in the international arena today is that while the U.S. is pulling back from the Mideast, and elsewhere, China is moving in but with a different strategic approach and overall agenda. Instead of bombs, missiles and coercive diplomacy, China is expanding its influence with the use of “soft power.” Indeed, U.S. overseas expansion was always overwhelmingly dependent on the use of hard power, and, as result, it would only leave black holes behind after its withdrawal. To what extent, as some might argue, is this the result of a young nation ignorant of history and with lack of experience in global affairs (although it would be hard to find any examples of benign imperialism)?

I don’t think the U.S. has forged new paths in Western imperial brutality. Simply consider its immediate predecessors in world control. British wealth and global power derived from piracy (such heroic figures as Sir Francis Drake), despoiling India by guile and violence, hideous slavery, the world’s greatest narcotrafficking enterprise, and other such gracious acts. France was no different. Belgium broke records in hideous crimes. Today’s China is hardly benign within its much more limited reach. Exceptions would be hard to find.

The two cases you mention have highly instructive features, brought out clearly, if unintentionally, by how they are depicted. Take an article in The New York Times about the growing China threat. The headline reads: “As the U.S. Pulls Back from the Mideast, China Leans in; expanding its ties to Middle Eastern states with vast infrastructure investments and cooperation on technology and security.”

That’s accurate; it’s one example of what’s happening all over the world. The U.S. is withdrawing military forces that have battered the Mideast region for decades in traditional imperial style. The evil Chinese are exploiting the retreat by expanding China’s influence with investment, loans, technology, development programs. What’s called “soft power.”

Not just in the Mideast. The most extensive Chinese project is the huge Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that is taking shape within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which incorporates the Central Asia states, India, Pakistan, Russia, now Iran, reaching to Turkey and with its eye on Central Europe. It may well include Afghanistan if it can survive its current catastrophe. Chinese aid and development might manage to shift the Afghan economy from heroin production for Europe, the core of the economy during the U.S. occupation, to exploitation of its rich mineral resources.

The BRI has offshoots in the Middle East, including Israel. There are accompanying programs in Africa, and now even Latin America, over strenuous U.S. objections. Recently, China announced that it’s taking over the manufacturing facilities in São Paulo that Ford abandoned, and will initiate large-scale electric vehicles production, an area in which China is far ahead.

The U.S. has no way to counter these efforts. Bombs, missiles, special forces raids in rural communities just don’t work.

It’s an old dilemma. Sixty years ago in Vietnam, U.S. counterinsurgency efforts were stymied by a problem that was despairingly recognized by U.S. intelligence and by Province Advisers: the Vietnamese resistance — the Viet Cong (VC), in U.S. discourse — were fighting a political war, a domain in which the U.S. was weak. The U.S. was responding with a military war, the arena in which it is strong. But that couldn’t overcome the appeal of VC programs to the peasant population.

The only way the Kennedy administration could react to the VC political war was by U.S. Air Force bombing of rural areas, authorizing napalm, large-scale crop and livestock destruction and other programs to drive the peasants to virtual concentration camps where they could be “protected” from the guerillas who the U.S. knew they were supporting. The consequences we know.

Earlier, the dilemma had been explained by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, addressing the National Security Council about U.S. problems with Brazil, where elites, he said, are “like children, with no capacity for self-government.” Worse still, in his words, the U.S. is “hopelessly far behind the Soviets in developing controls over the minds and emotions of unsophisticated peoples” of the Global South, even educated elites. Dulles lamented to the president about the Communist “ability to get control of mass movements, … something we have no capacity to duplicate. The poor people are the ones they appeal to and they have always wanted to plunder the rich.”

Dulles left unsaid the obvious: The poor people somehow don’t respond well to our appeal of the rich to plunder the poor, so with great reluctance we have to turn to the arena of violence, where we dominate.

That’s not unlike the dilemma posed when China “leans in” to the Global South by “expanding its ties with vast infrastructure investments and cooperation on technology and security.” That is one central element of the China threat that is eliciting such fears and anguish.

The U.S. is reacting to this growing China threat in the arena where it is strong. The U.S. of course has overwhelming military dominance worldwide, even right off the coast of China. But it’s being enhanced. Last December, military analyst Michael Klare reports, President Biden signed the National Defense Authorization Act. It calls for “an unbroken chain of U.S.-armed sentinel states — stretching from Japan and South Korea in the northern Pacific to Australia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore in the south and India on China’s eastern flank” — meant to encircle China.

Klare adds that, “Ominously enough Taiwan too is included in the chain of armed sentinel states.” The word “ominously” is well chosen. China of course regards Taiwan as part of China. So does the U.S., formally. The official U.S. one-China policy recognizes Taiwan as part of China, with a tacit agreement that no steps will be taken to forcefully change its status. Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo chipped away at this formula. It’s now being driven to the brink. China has the choice of either succumbing or resisting. It is not going to succumb.

This is only one component of the program to defend the U.S. from the China threat. A complementary element is to undermine China’s economy by means too well-known to review. In particular [in the U.S.’s eyes], China must be prevented from advancing in the technology of the future — actually extending its lead in some areas, such as electrification and renewable energy, the technologies that might save us from our race to destroy the environment that sustains life.

One aspect of these efforts to undermine China’s progress is to pressure other countries to reject superior Chinese technology. China has found a way to get around these efforts. They are planning to establish technical schools in countries of the Global South to teach advanced technology — Chinese technology, which graduates will then use. Again, the kind of aggression that is hard to confront.

U.S. influence is clearly declining across the international system, but one would not easily reach this conclusion by looking at the current U.S. National Security Strategy, which is still designed around the principle of the “two-war” doctrine even without expressly saying so. In this context, could it be argued that the U.S. empire is weakening in the 21st century, and that the end of the U.S. empire might not be a peaceful event?

It has been widely predicted in foreign policy circles for many years that China is poised to surpass the U.S. and to dominate world affairs, a dubious prospect, in my opinion, unless the U.S. continues on its current course of self-destruction, probably to be accelerated with the predicted congressional victory of the denialist party in November.

As we have discussed before, for some years the former Republican Party has been more accurately described as a “radical insurgency” that has abandoned normal parliamentary politics, to borrow the terms of political analysts Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute a decade ago — when Trump’s takeover of the insurgency was not yet a nightmare.

The Trump administration established a two-war doctrine in all but name. A war between two nuclear powers can quickly get out of control, meaning the end.

A step towards utter irrationality was taken last December 27, perhaps in celebration of Christmas, when President Biden signed the National Defense Authorization Act, discussed earlier, enhancing the policy of “encirclement” of China, “containment” being out of date. That includes formation of the Quad: U.S.-India-Japan-Australia, supplementing the AUKUS alliance (Australia, U.K., U.S.) and the Anglosphere’s Five Eyes, all of them strategic-military alliances confronting China. China has only a troubled hinterland. As discussed earlier, the radical military imbalance in favor of the U.S. is being enhanced by other provocative acts, carrying great risk. Apparently we cannot let down our guard with the Axis powers on the march once again.

It’s all too easy to sketch a likely trajectory that is far from a pleasant prospect. But we should never forget the usual proviso. We do not have to be passive spectators, thereby contributing to potential disaster.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

CJ Polychroniou

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

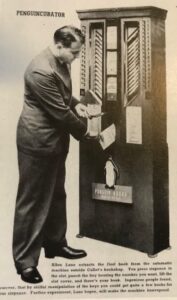

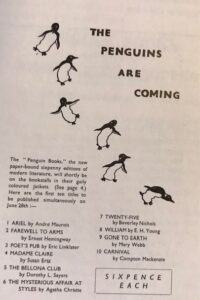

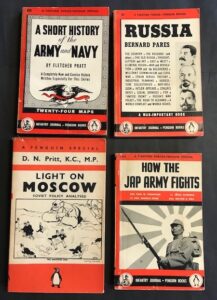

Volgens de gangbare legende ontstond het idee voor de bekende Penguin pockets bij de stationskiosk op het station van Exeter, in zuidwest Engeland. Allen Lane, redacteur bij de vermaarde uitgeverij The Bodley Head, wilde daar op een avond in 1935 de trein naar Londen nemen, na een logeerweekend in Devon te hebben doorgebracht bij detectiveschrijfster Agatha Christie en haar man, de archeoloog Max Mallowan. Hij verbaasde hij zich erover dat in de stationskiosk geen goedkope goede boeken te koop waren, in een voor een reiziger handzaam formaat, makkelijk mee te nemen dus, in de jaszak of reistas. Hij verwonderde zich ook over de abominabele inhoud van de aangeboden titels en de oppervlakkigheid van de genres in het assortiment. Ter plekke moet Lane bedacht hebben dat de markt rijp was voor het uitgeven van een serie voor iedereen betaalbare boeken in een handig formaat, die zich qua inhoud konden meten met de uitgaven van gevestigde Britse uitgeverijen. Literatuur, biografieën, poëzie, wetenschap en kunst, niet duurder dan de aanschaf van een pakje sigaretten.

Volgens de gangbare legende ontstond het idee voor de bekende Penguin pockets bij de stationskiosk op het station van Exeter, in zuidwest Engeland. Allen Lane, redacteur bij de vermaarde uitgeverij The Bodley Head, wilde daar op een avond in 1935 de trein naar Londen nemen, na een logeerweekend in Devon te hebben doorgebracht bij detectiveschrijfster Agatha Christie en haar man, de archeoloog Max Mallowan. Hij verbaasde hij zich erover dat in de stationskiosk geen goedkope goede boeken te koop waren, in een voor een reiziger handzaam formaat, makkelijk mee te nemen dus, in de jaszak of reistas. Hij verwonderde zich ook over de abominabele inhoud van de aangeboden titels en de oppervlakkigheid van de genres in het assortiment. Ter plekke moet Lane bedacht hebben dat de markt rijp was voor het uitgeven van een serie voor iedereen betaalbare boeken in een handig formaat, die zich qua inhoud konden meten met de uitgaven van gevestigde Britse uitgeverijen. Literatuur, biografieën, poëzie, wetenschap en kunst, niet duurder dan de aanschaf van een pakje sigaretten. Uitgevers

Uitgevers Kleuren

Kleuren Verzamelen

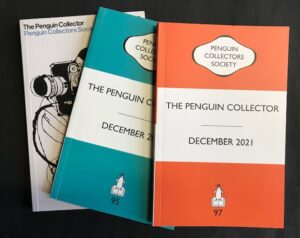

Verzamelen Genootschap

Genootschap Cartoonist

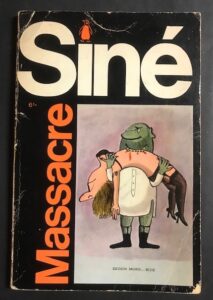

Cartoonist Godslasterlijk

Godslasterlijk