Noam Chomsky

Since World War I, propaganda has played a crucial role in warfare. Propaganda is used to increase support for the war among citizens of the nation that is waging it. National governments also use targeted propaganda campaigns in an attempt to influence public opinion and behavior in the countries they are at war with, as well as to influence international opinion. Essentially, propaganda, whether circulated through state-controlled or private media, refers to techniques of public opinion manipulation based on incomplete or misleading information, lies and deception. During World War II, both the Nazis and the Allies invested heavily in propaganda operations as part of each side’s overall effort to win the war.

The war in Ukraine is no different. Both Russian and Ukrainian leaders have undertaken a campaign of systematic dissemination of warfare information that can easily be designated as propaganda. Other parties with a stake in the conflict, such as the United States and China, are also engaged in propaganda operations, which work in tandem with their apparent lack of interest in diplomatic undertakings to end the war.

In the interview that follows, leading scholar and dissident Noam Chomsky, who, along with Edward Herman, constructed the concept of the “propaganda model,” looks at the question of who is winning the propaganda war in Ukraine. Additionally, he discusses how social media shape political reality today, analyzes whether the “propaganda model” still works, and dissects the role of the use of “whataboutism.” Lastly, he shares his thoughts on the case of Julian Assange and what his now almost certain extradition to the United States for having committed the “crime” of releasing public information about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq says about U.S. democratic principles.

Chomsky is internationally recognized as one of the most important intellectuals alive. His intellectual stature has been compared to that of Galileo, Newton and Descartes, as his work has had tremendous influence on a variety of areas of scholarly and scientific inquiry, including linguistics, logic and mathematics, computer science, psychology, media studies, philosophy, politics and international affairs. He is the author of some 150 books and the recipient of scores of highly prestigious awards, including the Sydney Peace Prize and the Kyoto Prize (Japan’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize), and of dozens of honorary doctorate degrees from the world’s most renowned universities. Chomsky is Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT and currently Laureate Professor at the University of Arizona.

C.J. Polychroniou: Wartime propaganda has become in the modern world a powerful weapon in garnering public support for war and providing a moral justification for it, usually by highlighting the “evil” nature of the enemy. It’s also used in order to break down the will of the enemy forces to fight. In the case of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Kremlin propaganda seems so far to be working inside Russia and dominating Chinese social media, but it looks like Ukraine is winning the information war in the global arena, especially in the West. Do you agree with this assessment? Any significant lies or war-myths around the Russia-Ukraine conflict worth pointing out?

Noam Chomsky: Wartime propaganda has been a powerful weapon for a long time, I suspect as far back as we can trace the historical record. And often a weapon with long-term consequences, which merit attention and thought.

Just to keep to modern times, in 1898, the U.S. battleship Maine sank in Havana harbor, probably from an internal explosion. The Hearst press succeeded in arousing a wave of popular hysteria about the evil nature of Spain. That provided the needed background for an invasion of Cuba that is called here “the liberation of Cuba.” Or, as it should be called, the prevention of Cuba’s self-liberation from Spain, turning Cuba into a virtual U.S. colony. So it remained until 1959, when Cuba was indeed liberated, and the U.S., almost at once, undertook a vicious campaign of terror and sanctions to end Cuba’s “successful defiance” of the 150-year-old U.S. policy of dominating the hemisphere, as the State Department explained 50 years ago.

Whipping up war myths can have long-term consequences.

A few years later, in 1916, Woodrow Wilson was elected president with the slogan “Peace without Victory.” That was quickly transmuted to Victory without Peace. A flood of war myths quickly turned a pacifist population to one consumed with hatred for all things German. The propaganda at first emanated from the British Ministry of Information; we know what that means. American intellectuals of the liberal Dewey circle lapped it up enthusiastically, declaring themselves to be the leaders of the campaign to liberate the world. For the first time in history, they soberly explained, war was not initiated by military or political elites, but by the thoughtful intellectuals — them — who had carefully studied the situation and after careful deliberation, rationally determined the right course of action: to enter the war, to bring liberty and freedom to the world, and to end the Hun atrocities concocted by the British Ministry of Information.

One consequence of the very effective Hate Germany campaigns was imposition of a victor’s peace, with harsh treatment of defeated Germany. Some strongly objected, notably John Maynard Keynes. They were ignored. That gave us Hitler.

In a previous interview, we discussed how Ambassador Chas Freeman compared the postwar Hate Germany settlement with a triumph of statesmanship (not by nice people): The Congress of Vienna, 1815. The Congress sought to establish a European order after Napoleon’s attempt to conquer Europe had been overcome. Judiciously, the Congress incorporated defeated France. That led to a century of relative peace in Europe.

There are some lessons.

Not to be outdone by the British, President Wilson established his own propaganda agency, the Committee on Public Information (Creel Commission), which performed its own services.

These exercises also had a long-term effect. Among the members of the Commission were Walter Lippmann, who went on to become the leading public intellectual of the 20th century, and Edward Bernays, who became a prime founder of the modern public relations industry, the world’s major propaganda agency, dedicated to undermining markets by creating uninformed consumers making irrational choices — the opposite of what one learns about markets in Econ 101. By stimulating rampant consumerism, the industry is also driving the world to disaster, another topic.

Both Lippmann and Bernays credited the Creel Commission for demonstrating the power of propaganda in “manufacturing consent” (Lippmann) and “engineering of consent” (Bernays). This “new art in the practice of democracy,” Lippmann explained, could be used to keep the “ignorant and meddlesome outsiders” — the general public — passive and obedient while the self-designated “responsible men” will attend to important matters, free from the “trampling and roar of a bewildered herd.” Bernays expressed similar views. They were not alone.

Lippmann and Bernays were Wilson-Roosevelt-Kennedy liberals. The conception of democracy they elaborated was quite in accord with dominant liberal conceptions, then and since.

The ideas extend broadly to the more free societies, where “unpopular ideas can be suppressed without the use of force,” as George Orwell put the matter in his (unpublished) introduction to Animal Farm on “literary censorship” in England.

So it continues. Particularly in the more free societies, where means of state violence have been constrained by popular activism, it is of great importance to devise methods of manufacturing consent, and to ensure that they are internalized, becoming as invisible as the air we breathe, particularly in articulate educated circles. Imposing war-myths is a regular feature of these enterprises.

It often works, quite spectacularly. In today’s Russia, according to reports, a large majority accept the doctrine that in Ukraine, Russia is defending itself against a Nazi onslaught reminiscent of World War II, when Ukraine was, in fact, collaborating in the aggression that came close to destroying Russia while exacting a horrific toll.

The propaganda is as nonsensical as war myths generally, but like others, it relies on shreds of truth, and has, it seems, been effective domestically in manufacturing consent.

We cannot really be sure because of the rigid censorship now in force, a hallmark of U.S. political culture from far back: the “bewildered herd” must be protected from the “wrong ideas.” Accordingly, Americans must be “protected” from propaganda which, we are told, is so ludicrous that only the most fully brainwashed could possibly keep from laughing.

According to this view, to punish Vladimir Putin, all material emanating from Russia must be rigorously barred from American ears. That includes the work of outstanding U.S. journalists and political commentators, like Chris Hedges, whose long record of courageous journalism includes his service as The New York Times Middle East and Balkans bureau chief, and astute and perceptive commentary since. Americans must be protected from his evil influence, because his reports appear on RT. They have now been expunged. Americans are “saved” from reading them.

Take that, Mr. Putin.

As we would expect in a free society, it is possible, with some effort, to learn something about Russia’s official position on the war — or as Russia calls it, “special military operation.” For example, via India, where Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov had a long interview with India Today TV on April 19.

We constantly witness instructive effects of this rigid indoctrination. One is that it is de rigueur to refer to Putin’s criminal aggression in Ukraine as his “unprovoked invasion of Ukraine.” A Google search for this phrase finds “About 2,430,000 results” (in 0.42 seconds).

Out of curiosity, we might search for “unprovoked invasion of Iraq.” The search yields “About 11,700 results” (in 0.35 seconds) — apparently from antiwar sources, a brief search suggests.

The example is interesting not only in itself, but because of its sharp reversal of the facts. The Iraq War was totally unprovoked: Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld had to struggle hard, even to resort to torture, to try to find some particle of evidence to tie Saddam Hussein to al-Qaeda. The famous disappearing weapons of mass destruction wouldn’t have been a provocation for aggression even if there had been some reason to believe that they existed.

In contrast, the Russian invasion of Ukraine was most definitely provoked — though in today’s climate, it is necessary to add the truism that provocation provides no justification for the invasion.

A host of high-level U.S. diplomats and policy analysts have been warning Washington for 30 years that it was reckless and needlessly provocative to ignore Russia’s security concerns, particularly its red lines: No NATO membership for Georgia and Ukraine, in Russia’s geostrategic heartland.

In full understanding of what it was doing, since 2014, NATO (meaning basically the U.S.), has “provided significant support [to Ukraine] with equipment, with training, 10s of 1000s of Ukrainian soldiers have been trained, and then when we saw the intelligence indicating a highly likely invasion Allies stepped up last autumn and this winter,” before the invasion, according to NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg.

The U.S. commitment to integrate Ukraine within the NATO command was also stepped up in fall 2021 with the official policy statements we have already discussed — kept from the bewildered herd by the “free press,” but surely read carefully by Russian intelligence. Russian intelligence did not have to be informed that “prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the United States made no effort to address one of Vladimir Putin’s most often stated top security concerns — the possibility of Ukraine’s membership into NATO,” as the State Department conceded, with little notice here.

Without going into any further details, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was clearly provoked while the U.S. invasion of Iraq was clearly unprovoked. That is exactly the opposite of standard commentary and reporting. But it is also exactly the norm of wartime propaganda, not just in the U.S., though it is more instructive to observe the process in free societies.

Many feel that it is wrong to bring up such matters, even a form of pro-Putin propaganda: we should, rather, focus laser-like on Russia’s ongoing crimes. Contrary to their beliefs, that stand does not help Ukrainians. It harms them. If we are barred, by dictate, from learning about ourselves, we will not be able to develop policies that will benefit others, Ukrainians among them. That seems elementary.

Further analysis yields many other instructive examples. We discussed Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Tribe’s praise for President George W. Bush’s decision in 2003 to “aid the Iraqi people” by seizing “Iraqi funds sitting in American banks” — and, incidentally, invading and destroying the country, too unimportant to mention. More fully, the funds were seized “to aid the Iraqi people and to compensate victims of terrorism,” for which the Iraqi people bore no responsibility.

We didn’t go on to ask how the Iraqi people were to be aided. It is a fair guess that it is not compensation for U.S. pre-invasion “genocide” in Iraq.

“Genocide” is not my term. Rather, it is the term used by the distinguished international diplomats who administered the “Oil-for-Food program,” the soft side of President Bill Clinton’s sanctions (technically, via the UN). The first, Denis Halliday, resigned in protest because he regarded the sanctions as “genocidal.” He was replaced by Hans von Sponeck, who not only resigned in protest with the same charge, but also wrote a very important book providing extensive details of the shocking torture of Iraqis by Clinton’s sanctions, A Different Kind of War.

Americans are not entirely protected from such unpleasant revelations. Though von Sponeck’s book was never reviewed, as far as I can determine, it can be purchased from Amazon (for $95) by anyone who has happened to hear about it. And the small publisher that released the English edition was even able to collect two blurbs: from John Pilger and me, suitably remote from the mainstream.

There is, of course, a flood of commentary about “genocide.” By the standards used, the U.S. and its allies are guilty of the charge over and over, but voluntary censorship prevents any acknowledgment of this, just as it protects Americans from international Gallup polls showing that the U.S. is regarded as by far the greatest threat to world peace, or that world public opinion overwhelmingly opposed the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan (also “unprovoked,” if we pay attention), and other improper information.

I don’t think there are “significant lies” in war reporting. The U.S. media are generally doing a highly creditable job in reporting Russian crimes in Ukraine. That’s valuable, just as it’s valuable that international investigations are underway in preparation for possible war crimes trials.

That pattern is also normal. We are very scrupulous in unearthing details about crimes of others. There are, to be sure, sometimes fabrications, sometimes reaching the level of comedy, matters that the late Edward Herman and I documented in extensive detail. But when enemy crimes can be observed directly, on the ground, journalists typically do a fine job reporting and exposing them. And they are explored further in scholarship and extensive investigations.

As we’ve discussed, on the very rare occasions when U.S. crimes are so blatant that they can’t be dismissed or ignored, they may also be reported, but in such a way as to conceal the far greater crimes to which they are a small footnote. The My Lai massacre, for example.

On Ukraine winning the information war, the qualification “in the West” is accurate. The U.S. has always been enthusiastic and rigorous in exposing crimes of its enemies, and in the current case, Europe is going along. But outside of U.S.-Europe, the picture is more ambiguous. In the Global South, the home of most of the world’s population, the invasion is denounced but the U.S. propaganda framework is not uncritically adopted, a fact that has led to considerable puzzlement here as to why they are “out of step.”

That’s quite normal too. The traditional victims of brutal violence and repression often see the world rather differently from those who are used to holding the whip.

Even in Australia, there’s a measure of insubordination. In the international affairs journal Arena, editor Simon Cooper reviews and deplores the rigid censorship and intolerance of even mild dissent in U.S. liberal media. He concludes, reasonably enough, that, “This means it is almost impossible within mainstream opinion to simultaneously acknowledge Putin’s insupportable actions and forge a path out of the war that does not involve escalation, and the further destruction of Ukraine.”

No help to suffering Ukrainians, of course.

That’s also nothing new. That has been a dominant pattern for a long time, notably during World War I. There were a few who didn’t simply conform to the orthodoxy established after Wilson joined the war. The country’s leading labor leader, Eugene Debs, was jailed for daring to suggest to workers that they should think for themselves. He was so detested by the liberal Wilson administration that he was excluded from Wilson’s postwar amnesty. In the liberal Deweyite intellectual circles, there were also some who were disobedient. The most famous was Randolph Bourne. He was not imprisoned but was barred from liberal journals so that he could not spread his subversive message that “war is the health of the state.”

I should mention that a few years later, much to his credit, Dewey himself sharply reversed his stand.

It is understandable that liberals should be particularly excited when there is an opportunity to condemn enemy crimes. For once, they are on the side of power. The crimes are real, and they can march in the parade that is rightly condemning them and be praised for their (quite proper) conformity. That is very tempting for those who sometimes, even if timidly, condemn crimes for which we share responsibility and are therefore castigated for adherence to elementary moral principles.

Has the spread of social media made it more or less difficult to get an accurate picture of political reality?

Hard to say. Particularly hard for me to say because I avoid social media and only have limited information. My impression is that it is a mixed story.

Social media provide opportunities to hear a variety of perspectives and analyses, and to find information that is often unavailable in the mainstream. On the other hand, it is not clear how well these opportunities are exploited. There has been a good deal of commentary — confirmed by my own limited experience — arguing that many tend to gravitate to self-reinforcing bubbles, hearing little beyond their own beliefs and attitudes, and worse, entrenching these more firmly and in more intense and extreme forms.

That aside, the basic news sources remain pretty much as they were: the mainstream press, which has reporters and bureaus on the ground. The internet offers opportunities to sample a much wider range of such media, but my impression, again, is that these opportunities are little used.

One harmful consequence of the rapid proliferation of social media is the sharp decline of mainstream media. Not long ago, there were many fine local media in the U.S. Mostly gone. Few even have Washington bureaus, let alone elsewhere, as many did not long ago. During Ronald Reagan’s Central America wars, which reached extremes of sadism, some of the finest reporting was done by reporters of the Boston Globe, some close personal friends. That has all virtually disappeared.

The basic reason is advertiser reliance, one of the curses of the capitalist system. The founding fathers had a different vision. They favored a truly independent press and fostered it. The Post Office was largely established for this purpose, providing cheap access to an independent press.

In keeping with the fact that it is to an unusual extent a business-run society, the U.S. is also unusual in that it has virtually no public media: nothing like the BBC, for example. Efforts to develop public service media — first in radio, later in TV — were beaten back by intense business lobbying.

There’s excellent scholarly work on this topic, which extends also to serious activist initiatives to overcome these serious infringements on democracy, particularly by Robert McChesney and Victor Pickard.

Nearly 35 years ago, you and Edward Herman published Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. The book introduced the “propaganda model” of communication which operates through five filters: ownership, advertising, the media elite, flak and the common enemy. Has the digital age changed the “propaganda” model?” Does it still work?

Unfortunately, Edward — the prime author — is no longer with us. Sorely missed. I think he would agree with me that the digital age hasn’t changed much, beyond what I just described. What survives of mainstream media in a largely business-run society still remains the main source of information and is subject to the same kinds of pressures as before.

There have been important changes apart from what I briefly mentioned. Much like other institutions, even including the corporate sector, the media have been influenced by the civilizing effects of the popular movements of the ‘60s and their aftermath. It is quite illuminating to see what passed for appropriate commentary and reporting in earlier years. Many journalists have themselves gone through these liberating experiences.

Naturally, there is a huge backlash, including passionate denunciations of “woke” culture that recognizes that there are human beings with rights apart from white Christian males. Since Nixon’s “Southern strategy,” the GOP leadership has understood that since they cannot possibly win votes on their economic policies of service to great wealth and corporate power, they must try to direct attention to “cultural issues”: the false idea of a “Great Replacement,” or guns, or indeed anything to obscure the fact that we’re working hard to stab you in the back. Donald Trump was a master of this technique, sometimes called the “thief, thief” technique: when you’re caught with your hand in someone’s pocket, shout “thief, thief” and point somewhere else.

Despite these efforts, the media have improved in this regard, reflecting changes in the general society. That’s by no means unimportant.

What do you make of “whataboutism,” which is stirring up quite a controversy these days on account of the ongoing war in Ukraine?

Here again there’s a long history. In the early postwar period [World War II], independent thought could be silenced by charges of comsymp: you’re an apologist for Stalin’s crimes. It’s sometimes condemned as McCarthyism, but that was only the vulgar tip of the iceberg. What is now denounced as “cancel culture” was rampant and remained so.

That technique lost some of its power as the country began to awaken from dogmatic slumber in the ‘60s. In the early ‘80s, Jeane Kirkpatrick, a major Reaganite foreign policy intellectual, devised another technique: moral equivalence. If you reveal and criticize the atrocities that she was supporting in the Reagan administration, you’re guilty of “moral equivalence.” You’re claiming that Reagan is no different than Stalin or Hitler. That served for a time to subdue dissent from the party line.

Whataboutism is a new variant, hardly different from its predecessors.

For the true totalitarian mentality, none of this is enough. GOP leaders are working hard to cleanse the schools of anything that is “divisive” or that causes “discomfort.” That includes virtually all of history apart from patriotic slogans approved by Trump’s 1776 Commission, or whatever will be devised by GOP leaders when they take command and are in a position to impose stricter discipline. We see many signs of it today, and there’s every reason to expect more to come.

It’s important to remember how rigid doctrinal controls have been in the U.S. — perhaps a reflection of the fact that it is a very free society by comparative standards, hence posing problems to the doctrinal managers, who must be ever alert to signs of deviation.

By now, after many years, it’s possible to utter the word “socialist,” meaning moderately social democrat. In that respect, the U.S. has finally broken out of the company of totalitarian dictatorships. Go back 60 years and even the words “capitalism” and “imperialism” were too radical to voice. Students for a Democratic Society President Paul Potter, in 1965, summoned the courage to “name the system” in his presidential address, but couldn’t manage to produce the words.

There were some breakthroughs in the ‘60s, a matter of deep concern to American liberals, who warned of a “crisis of democracy” as too many sectors of the population tried to enter the political arena to defend their rights. They counseled more “moderation in democracy,” a return to passivity and obedience, and they condemned the institutions responsible for “indoctrination of the young” for failing to perform their duties.

The doors have been opened more widely since, which only calls for more urgent measures to impose discipline.

If GOP authoritarians are able to destroy democracy sufficiently to establish permanent rule by a white supremacist Christian nationalist caste subservient to extreme wealth and private power, we are likely to enjoy the antics of such figures as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who banned 40 percent of children’s math texts in Florida because of “references to Critical Race Theory (CRT), inclusions of Common Core, and the unsolicited addition of Social Emotional Learning (SEL) in mathematics,” according to the official directive. Under pressure, the State released some terrifying examples, such as an educational objective that, “Students build proficiency with social awareness as they practice with empathizing with classmates.”

If the country as a whole ascends to the heights of GOP aspirations, it will be unnecessary to resort to such devices as “moral equivalence” and “whataboutism” to stifle independent thought.

One final question. A U.K. judge has formally approved Julian Assange’s extradition to the U.S. despite deep concerns that such a move would put him at risk of “serious human rights violations,” as Agnès Callamard, former UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions, had warned a couple of years ago. In the event that Assange is indeed extradited to the U.S., which is pretty close to certain now, he faces up to 175 years in prison for releasing public information about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Can you comment on the case of Julian Assange, the law used to prosecute him, what his persecution says about freedom of speech and the state of U.S. democracy?

Assange has been held for years under conditions that amount to torture. That’s fairly evident to anyone who was able to visit him (I was, once) and was confirmed by the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture [and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment] Nils Melzer in May 2019.

A few days later, Assange was indicted by the Trump administration under the Espionage Act of 1917, the same act that President Wilson employed to imprison Eugene Debs (among other state crimes committed using the Act).

Legalistic shenanigans aside, the basic reasons for the torture and indictment of Assange are that he committed a cardinal sin: he released to the public information about U.S. crimes that the government, of course, would prefer to see concealed. That is particularly offensive to authoritarian extremists like Trump and Mike Pompeo, who initiated the proceedings under the Espionage Act.

Their concerns are understandable. They were explained years ago by the Professor of the Science of Government at Harvard, Samuel Huntington. He observed that, “Power remains strong when it remains in the dark; exposed to the sunlight it begins to evaporate.”

That is a crucial principle of statecraft. It extends to private power as well. That is why manufacture/engineering of consent is a prime concern of systems of power, state and private.

This is no novel insight. In one of the first works in what is now called political science, 350 years ago, his “First Principles of Government,” David Hume wrote that,

Nothing appears more surprising to those, who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than the easiness with which the many are governed by the few; and the implicit submission, with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers. When we enquire by what means this wonder is effected, we shall find, that, as Force is always on the side of the governed, the governors have nothing to support them but opinion. It is therefore, on opinion only that government is founded; and this maxim extends to the most despotic and most military governments, as well as to the most free and most popular.

Force is indeed on the side of the governed, particularly in the more free societies. And they’d better not realize it, or the structures of illegitimate authority will crumble, state and private.

These ideas have been developed over the years, importantly by Antonio Gramsci. The Mussolini dictatorship understood well the threat he posed. When he was imprisoned, the prosecutor announced that, “We must prevent this brain from functioning for 20 years.”

We have advanced considerably since fascist Italy. The Trump-Pompeo indictment seeks to silence Assange for 175 years, and the U.S. and U.K. governments have already imposed years of torture on the criminal who dared to expose power to the sunlight.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

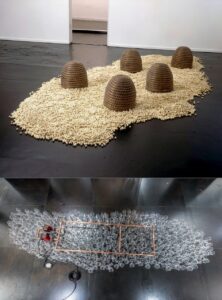

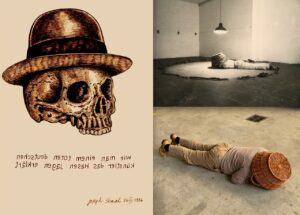

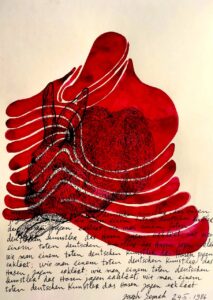

On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV – How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist

On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV – How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist In het werk van kunstenaar Joseph Beuys is de christelijke iconografie een van de belangrijkste thema’s, met name de Christus impuls.

In het werk van kunstenaar Joseph Beuys is de christelijke iconografie een van de belangrijkste thema’s, met name de Christus impuls.