Noam Chomsky

Since the mid-1990s, the United Nations has been launching global climate summits — called COPs — which stands for Conference of the Parties. Last year was the 26th annual summit and took place in Glasgow. COP26 was supposed to be “a pivotal moment for the planet,” but the outcomes fell way short of the action needed to stop the climate crisis from becoming utterly catastrophic. This year, COP27 will be held in Egypt in the midst of an energy crisis and a war that is reshaping the global order.

Will COP27 end up as yet another failure on the part of world leaders to slow or stop global warming? Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin share their thoughts and insights on the climate crisis conundrum by dissecting the current state of affairs and what ought to be done to stop humanity’s march to the climate precipice.

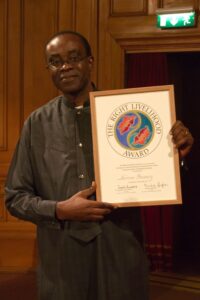

Noam Chomsky is institute professor emeritus in the department of linguistics and philosophy at MIT and laureate professor of linguistics and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Program in Environmental and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. One of the world’s most cited scholars in modern history and a critical public intellectual regarded by millions of people as a national and international treasure, Chomsky has published more than 150 books in linguistics, political and social thought, political economy, media studies, U.S. foreign policy and world affairs, and climate change.

Robert Pollin

Robert Pollin is distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. One of the world’s leading progressive economists, Pollin has published scores of books and academic articles on jobs and macroeconomics, labor markets, wages, and poverty, environmental and energy economics. He was selected by Foreign Policy Magazine as one of the “100 Leading Global Thinkers for 2013.” Chomsky and Pollin are coauthors of Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (2020).

C.J. Polychroniou: The 27th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP27) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) will take place in Egypt from November 6-18, 2022. Nearly 200 countries will come together in yet another attempt to tackle climate breakdown. COP26, held in Glasgow about the same time last year had been hailed as “our last best hope,” but it did not achieve much as too many compromises were made. The hope for COP27 is that the world will set more stringent greenhouse gas emissions reduction requirements considering the ever-clearer consequences of global warming. Noam, is this a significant climate meeting? Can we expect a breakthrough, or will it end up yet another futile international effort to reverse climate change? Indeed, what’s standing on the way of governments’ failure to slow or even reverse global warming? Isn’t the evidence already overwhelming that the world stands on a climate precipice? What prevent us from stepping back from the abyss?

Noam Chomsky: Decisions by governments tend to reflect the distribution of power in the society. As Adam Smith phrased this virtual truism in his classic work, “the masters of mankind” — in his day, the merchants and manufacturers of England — are the “principal architects” of government policy and act to ensure that their own interests will be “most peculiarly attended to” no matter how “grievous” the effects on the general welfare. Insofar as governments have failed to act in the ways that will prevent catastrophe, it is because the principal architects of policy have higher priorities.

Let’s take a look. The U.S. government has just passed a climate bill, a pale shadow of what was proposed by the Biden administration under the impact of popular climate activism, which in the end could not compete with the power of the true masters in the corporate sector. The final shadow is not meaningless. It is, however, radically insufficient in its reach, and also burdened with measures to ensure that the interests of the masters are “most peculiarly attended to.”

The bill that the masters were willing to accept includes vast government subsidies that “are already driving forward large oil and gas projects that threaten a heavy carbon footprint, with companies including ExxonMobil, Sempra and Occidental Petroleum positioned for big payouts,” the Washington Post reports. One device to satisfy the needs of the masters is “a vast wad of money” for carbon capture — a phrase that means: “Let’s keep poisoning the atmosphere freely and maybe someday someone will figure out a way to remove the poisons.”

That’s too kind. It’s much worse. “The irony of carbon capture is that the place it has proven most successful is getting more oil out of the ground. All but one major project built in the United States to date is geared toward fossil fuel companies taking the trapped carbon and injecting it into underground wells to extract crude.”

The actual cases would be comical if the consequences were not so grave. Thus “The subsidies give companies lucrative incentives to drill for gas in the most climate-unfriendly sites, where the concentration of CO2 in the fuel is especially high. The CO2, a potent greenhouse gas, is useless for making fuel, but the tax credits are awarded based on how many tons of it companies trap.”

It’s hard to believe that this is real. But it is. It’s capitalism 101 when the masters are in charge.

Other cases illustrate the same priorities. Arctic permafrost contains huge amounts of carbon and is beginning to melt as the Arctic heats much faster than the rest of the world. Scientists of one oil major, ConocoPhillips, discovered a way to slow the thawing of the permafrost. To what end? “To keep it solid enough to drill for oil, the burning of which will continue to worsen ice melt,” according to the New York Times.

The exuberant race to destruction is far more general. New fields are being opened to exploration. There is a huge expansion of oil pipelines, with “more than 24,000km of pipelines planned around world, showing ‘an almost deliberate failure to meet climate goals.’”

Corporate lobbyists are even pressing states to punish corporations (by withdrawing pension funds etc.) that dare even to provide information on environmental impacts of their policies. No stone is left unturned. Every opportunity to destroy must be exploited, no matter how slight, following Marx’s script of capitalism going berserk.

It is not really surprising that once Reagan and Thatcher launched the current era of savage class war, removing all constraints, the masters used the opportunity to pursue their “vile maxim, all for ourselves and nothing for anyone else,” as Smith advised us 250 years ago.

There is a certain logic behind it. The rules of the game are that you expand profit and market share, or you lose out. For self-delusion, it suffices to hold out the thin hope that maybe our technical culture will find some answers.

There is an alternative to the resolute march toward suicide. The distribution of power can be changed by an aroused public with its own very different priorities, such as surviving in a livable world. The current masters can be controlled on a path toward elimination of their illegitimate authority. The rules of the game can be changed, in the short term modified sufficiently to enable humankind to adopt the means that have been spelled out in detail to “step back from the abyss.”

Polychroniou: Bob, can you give us an estimate of where we stand on climate change and what needs to be done for the world to become carbon neutral by 2050?

Robert Pollin: Where we stand with climate change is straightforward and was expressed clearly in the most recent two massive reports, of this past February and April 2022, from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the most authoritative mainstream resource on climate change research. In summarizing its February report, the IPCC said that “Human-induced climate change is causing dangerous and widespread disruption in nature and affecting the lives of billions of people around the world, despite efforts to reduce the risks. People and ecosystems least able to cope are being hardest hit.” The February report describes how “Increased heatwaves, droughts and floods are already exceeding plants’ and animals’ tolerance thresholds, driving mass mortalities in species such as trees and corals. These weather extremes are occurring simultaneously, causing cascading impacts that are increasingly difficult to manage. They have exposed millions of people to acute food and water insecurity, especially in Africa, Asia, Central and South America, on Small Islands and in the Arctic.” I would note that reputable climate scientists regularly criticize the IPCC for understating our dire ecological condition.

What we need to do to have any chance of stabilizing the climate is also straightforward. By far, the biggest driver of climate change is burning oil, coal and natural gas to produce energy. This is because burning fossil fuels to produce energy generates CO2 emissions. These emissions, in turn, are the main cause of heat being trapped in our atmosphere and warming the planet. This is why, in its landmark 2018 special report, “Global Warming of 1.5° Celsius,” the IPCC set out the overarching goals of cutting global CO2 emissions by about 50 percent as of 2030 and for the globe to reach net zero emissions by 2050. The IPCC concluded in the 2018 report, and emphasized even more emphatically in its 2022 studies, that stabilizing the global climate at 1.5 degrees Celsius (1.5°C) above pre-industrial average temperature levels is imperative for having any chance of reducing significantly, much less preventing the “dangerous and widespread disruption in nature affecting the lives of billions of people around the world.”

It is clear then that the single most important project for advancing a viable climate stabilization program is to phase out the consumption of oil, coal and natural gas for energy production. As the fossil fuel energy infrastructure phases out to zero by 2050, we concurrently have to build an entirely new global energy infrastructure whose centerpieces will be high efficiency and clean renewable energy sources — primarily solar and wind power. People are obviously still going to need to consume energy, from any available source, to light, heat and cool buildings, to power cars, buses, trains and airplanes, and to operate computers and industrial machinery, among other uses. Moreover, any minimally decent egalitarian program climate stabilization program — what we may call a Global Green New Deal — will entail a significant increase in energy consumption for lower-income people throughout the world.

The other major driver of climate change is corporate industrial agriculture in its multiple manifestations. This includes the heavy reliance on natural gas-based fertilizers along with synthetic pesticides and herbicides to increase land productivity. It also includes deforestation, whose main purpose is to increase available land for cattle grazing and still more industrial farming. Addressing these causes of climate change is, at least in principle, also straightforward. It requires replacing industrial agriculture with organic farming practices that rely on crop rotation, animal manures and composting for fertilizer and biological pest control. It means humans eating less beef, and thereby freeing up the cattle-grazing land to be used for organic crop cultivation. It then also means stopping deforestation, most especially in the Amazon rainforest i.e., “the Earth’s lungs.” This is why, as Noam emphasized in a previous recent interview, it is absolutely imperative, just on the climate issue alone, that Lula defeats Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil’s presidential election on October 30. Bolsonaro has no compunctions about obliterating the Amazon rainforest if there is money to be made, while Lula is committed to rainforest preservation and reforestation.

So, in response to both of your questions — where we stand today on climate change and what needs to be done — we will have a clearer picture after Brazil’s October 30 election. We can also generalize from Brazil’s situation. That is, everywhere in the world, we need to elect people like Lula and to defeat all climate deniers and apologists for the fossil fuel industry, that is, all the Bolsonaros in all regions of the world.

At the same time, electoral politics by itself is never going to be a sufficient action program. Even principled political leaders like Lula can become susceptible to backsliding from a robust Green New Deal program in the face of the enormous pressures from fossil fuel corporations who continue to cash in on destroying the planet. The only solution here is mass organizing that is capable of holding all politicians accountable. There has been tremendous climate activism throughout the world in recent years, led by young people. This activism simply needs to intensify and continue to become increasingly impactful.

In terms of some specifics, the investments required to dramatically increase energy efficiency standards and equally dramatically expand the global supply of clean energy sources will be a major source of new job creation, in all regions of the world. This is excellent news, as far as it goes. But there is no guarantee that these new jobs will be good jobs. After all, we are still operating within capitalism. Climate activists therefore need to join forces with unions and other labor organizers to fight for good wages, benefits and working conditions for these millions of new clean energy jobs. At the same time, the phasing out of the global fossil fuel industry will mean large-scale losses for workers and communities that are presently dependent on the fossil fuel industry. Providing a just transition for these workers and communities also needs to be at the center of the Global Green New Deal.

There have been some recent positive developments with respect to the energy transition. Clean renewable energy investments have increased for the past two years, at a rate of about 12 percent per year. This contrasts sharply with the five years immediately after the major COP21 conference in Paris in 2015, during which global clean energy investments rose by a paltry 2 percent annual rate.

This recent spike in clean energy investments is being fueled by the fact that the costs of solar and wind power are falling dramatically and are now lower than those for fossil fuels and nuclear. Thus, as of 2020, the average cost for fossil fuel-generated electricity ranged between 5.5-14.8 cents per kilowatt hour in the high-income economies. These cost figures then rose sharply in 2021, due to the post COVID lockdown supply-chain breakdowns in the fossil fuel industry and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. By contrast, as of 2021, solar photovoltaic installations generate electricity at 4.8 cents per kilowatt hour and onshore wind is at 3.3 cents. Moreover, average solar costs fell by roughly 90 percent between 2010-2021. The average cost figures for solar and wind should continue to decline still further as advances in technology proceed as long as the rapid global expansion of these sectors continues.

At the same time, these positive developments must be weighed against the grim bottom-line reality that, to date, there is still no evidence that global CO2 emissions have begun falling. A modest reduction did occur in 2020 due to the global COVID lockdown. But as of 2019, global CO2 emissions stood at 37 billion tons. This is a 50 percent increase relative to 2000 and a 12 percent increase relative to just 2010. Overall, the transition from a fossil fuel dominant to a high-efficiency and renewables dominant global energy infrastructure, to rainforest preservation and an organic farming dominant agricultural infrastructure needs to be dramatically accelerated for there to be any chance of hitting the IPCC’s climate stabilization targets.

We also need to recognize that this transition needs to occur everywhere, in all countries, regardless of their current emissions or income levels. This becomes clear through some simple global emissions accounting. As of now, China and the U.S. are by far most responsible for current total emissions. China’s emissions represent 31 percent of the current global total and the United States accounts for another 14 percent. So, adding emissions from China and the U.S. alone gets us to 45 percent of the global total. But we can look at this same statistic from the opposite direction: Even after combining the emissions levels for China and the U.S., we still haven’t accounted for fully 55 percent of total global emissions. We can then include the emissions totals for the 27 countries of the European Union along with China and the U.S. This adds another 8 percent to current total emissions, getting us to 53 percent in total. This means that if we only pay attention to China, the U.S. and the European Union countries, we still are neglecting the countries responsible for generating nearly half of current total global emissions. The point is that every place does matter if we really are going to hit the target of net zero global emissions by no later than 2050. Zero emissions has to really mean zero, everywhere.

Polychroniou: COP27 has been called Africa’s COP. Indeed, Africa contributes only 3 percent to greenhouse gas emissions but suffers disproportionately from its negative effects. To be sure, the issue of who should pay for “loss and damages” from the climate crisis will occupy center stage at COP27. What are your thoughts on this matter? We already know, for instance, that the EU won’t back climate damage funds talks at COP, and I don’t think we should expect a different attitude from the United States. Is there a case to be made for climate reparations? Is there a better alternative?

Pollin: From an historical perspective, the high-income countries, starting with the U.S. but also including Canada, Western Europe, Europe and Australia are almost entirely responsible for loading up the atmosphere with greenhouse gas emissions and causing climate change. They therefore should be primarily responsible for financing the Global Green New Deal. But more recently, as I noted above, China is producing much larger emissions than any other country. China can therefore not be let off the hook as a source of climate financing.

But we also need to recognize that high-income people in all countries and regions have massively larger carbon footprints than everyone else. The average carbon footprint of someone in the richest 10 percent of the global population is 60 times greater than of someone in the poorest 10 percent. From this perspective, the financing of a Global Green New Deal must fall disproportionately on the rich in all countries.

However, more generally, it is not accurate or constructive to consider the issue of financing the energy system transformation as simply a question of who bears how much of the overall burden. We also need to recognize that the overall burden is actually not excessively large and that building a global green economy will also generate huge benefits and opportunities. Consider, for example, just the following:

1. According to my own research and that of others, a global climate stabilization program capable of achieving the zero emissions goal by 2050 will entail clean energy investment spending of roughly $4.5 trillion per year through 2050. This totals to about $120 trillion over the full period. These are eye-popping numbers from one angle. Yet they amount to an average of only about 2.5 percent of total global income (GDP) between now and 2050. In other words, we can transform the global energy system and save the planet while still spending something like 97 percent of total global income on everything besides clean energy investments. This is also while average incomes are rising over time.

2. Creating a clean global energy infrastructure will pay for itself over time and save money for all energy consumers. This is because energy efficiency investments, by definition, mean spending less money to get the same amount of energy services — like keeping one’s home well-lit and warm in the winter. Moreover, as I noted above, the costs of delivering a kilowatt of electricity from renewable energy sources is already lower, on average, than getting the same kilowatt from fossil fuels or nuclear power sources, and the costs of renewable energy are falling.

3. Building the clean energy infrastructure will be more decentralized than the current highly capital-intensive and big corporate dominated fossil fuel infrastructure. Solar energy systems can be installed on rooftops and parking lots and in one’s neighborhood. Wind turbines can be located on farmland without sacrificing productivity in crop or livestock cultivation. This, in turn, will create opportunities to expand access to energy into low-income communities throughout the world, including in the rural regions of low-income countries. Roughly half the people living in these regions do not currently have access to electricity at all.

Overall then, building the global clean energy economy should be understood as a great opportunity for investors and consumers, including especially small-scale investors such as both public and private cooperative enterprises.

That said, it will of course still be necessary to deliver the up-front money to pay for the initial investments. There is no shortage of big pots money that can be tapped in equitable ways for this purpose. We can start with transferring funds out of military budgets for all countries. Since the U.S. military budget amounts to 40 percent of global military spending, transferring, say, 5 percent of all military spending into global climate investments will mean that the U.S. share of the funds will also amount to about 40 percent of the global total. We can also eliminate existing fossil fuel subsidies in all countries and convert them into clean energy subsidies. The central banks of rich countries can purchase green bonds to support investments both within their own countries as well as globally. They then will receive the revenues that will be generated by these investments. The central banks of rich countries did not hesitate to provide massive bailout funding to financial markets during the COVID lockdown, at levels of 10 percent or more of their countries’ respective GDPs. The global green bond fund could amount to perhaps one-tenth the size of these bailout programs. Finally, carbon taxes can be a viable source of funds as long as the tax burden falls mostly on high-income consumers and most of the revenue generated by the tax is rebated back to middle and low-income energy consumers.

The global financing project will then also need to be supported by private investors, at a level at least equal to that of government funds. Yet we know that private investors will never deliver sufficient funds without public policies in place that enforce hard limits on profit opportunities through fossil fuel investments, if not eliminating such profit opportunities altogether. The windfall tax on oil company profits proposed in the U.S. Congress by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse and Rep. Ro Khanna is one good place to start.

The need for such measures has become ever clearer since the fiasco surrounding the pledges made by major private financial institutions coming out of last year’s COP26 climate conference in Glasgow. Perhaps the biggest single story coming out of the Glasgow conference was the formation of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), a group of roughly 500 financial sector firms holding $130 trillion in overall assets — i.e., something like one-third of total global private financial assets. At the conference, GFANZ members committed their institutions to supporting investments that will deliver a zero-emissions global economy by 2050. But now many of the biggest players in the coalition are abandoning their pledges. The explanation is simple, as reported in Bloomberg Green: “The revived fortunes of fossil fuels, especially coal, may explain some of the weakened resolve for decarbonization. Global bank lending to fossil fuel companies is up 15 percent to over $300 billion in the first nine months of this year from the same period in 2021.” Justin Guay, director of climate finance strategy at the Sunrise Project summed up the matter perfectly in commenting: “Banks were happy to sign up to a big pageantry contest at COP26 and get a bunch of applause. But when they realized the world expected them to make good on what they said they would do, they have looked for convenient excuses to wiggle out of that responsibility.”

Polychroniou: Noam, what do you think about this matter? The so-called “triple crisis” — i.e., responsibility, mitigation and adaptation — need to be addressed by the countries most responsible for climate breakdown, according to both climate activists and various governments of the Global South, including Egypt, the host of COP27.

Chomsky: We can refine the question. More accurately it is the rich in the rich countries who are most responsible for climate breakdown, and much more. Right now, working people in the super-rich United States are suffering from severe inflation, much of which is caused by the sharp rise in oil prices triggered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Meanwhile the profits of the fossil fuel industrial complex are booming. One short-term remedy would be a tax on their rapacious pursuit of the vile exam, proposed in legislation aimed at oil price gouging introduced by Senators Sherrod Brown and Sheldon Whitehouse, with receipts going directly to consumers. Much more far-reaching steps can easily be envisioned.

These questions should be considered against the background of the neoliberal class war of the past 40 years, which has transferred some $50 trillion to the pockets of the super-rich 1 percent. Bob Pollin reminds us that the steady rise in real wages ended in the ‘70s as the business campaign against working people and the poor was taking shape, with the floodgates opened by Reagan and Thatcher. If real wages had continued to track productivity gains, “the average worker’s hourly wage in 2021 would have been $61.94, not $25.18.” And if the assault on the public had been curbed, big corporate CEO pay would not have risen “from being 33 times higher than the average worker in 1978 to 366 times higher in 2019—i.e., a more than tenfold increase in relative pay.” That’s only one part of the serious blows against working people and the poor that we expect, on institutional grounds, once the reins are cast off.

All of this is background for considering the “triple crisis.” The Global Green New Deal should confront these issues directly and forcefully, not just by proper concern for the countries that have been victimized by global warming but also by dismantling the class basis of the depredations of past centuries, sometimes taking truly savage forms as in the recent neoliberal years.

The immediate crisis is too urgent for the radical social change that we should seek, but efforts to carry it forward should proceed in tandem with addressing urgent demands. If basic capitalist institutions remain in place, the Global Green New Deal will not proceed as far as it must if we are to have a livable world that values freedom and justice.

Polychroniou: The Global Green New Deal may represent our only hope for an effective opportunity to address the challenge of global warming while also setting the world economy on a new course of sustainable development. Yet, it wasn’t part of COP26’s decarbonization concerns and it doesn’t figure in the agenda of COP27. Why?

Chomsky: Who meets in the stately halls where agendas are devised?

Let’s return to our discussion of the achievements of COP26. The most exciting, eliciting much euphoria, was the commitment of the great private financial institutions to devote up to $130 trillion to such noble projects as wiring Africa for solar power. The market to the rescue! — with a small footnote, as political economist Adam Tooze was unkind enough to add. The giants of finance will gladly make their lavish contribution to the Global Green New Deal if the International Monetary Fund and World Bank “derisk” the loans by absorbing losses and “there is a carbon price that gives clean energy a competitive advantage.”

As long as the vile maxim is firmly in place, their munificence has no bounds.

We return to the same conclusions. The Global Green New Deal cannot be delayed, but it must go hand in hand with raising consciousness and implementing measures to constrain and ultimately dismantle the institutional structures of capitalist autocracy.

Polychroniou: Bob, you are one of the leading advocates of global Green New Deal. Why isn’t this project gaining traction? Too idealistic for the taste of the real world where national interests still reign supreme? If so, what needs to be done?

Pollin: As I have tried to convey in my responses above, I don’t see the Global Green New Deal as idealistic. I rather see it as the only viable program that can achieve the IPCC’s climate stabilization goals in a way that also expands decent job opportunities and raises mass living standards in all regions of the world, at all levels of development. That includes increasing peoples’ access to low-cost energy throughout the world. As such, the Global Green New Deal should attract overwhelming support, both among people who are committed around climate issues as well as those whose primary focus may be paying rent and keeping food on the table.

Achieving this level of support can only be achieved through organizing and educating. To take one example, for over a decade, labor and environment activists, such as those associated with the Labor Network for Sustainability and the BlueGreen Alliance in the U.S., have been working to build strong coalitions. Against steep odds, they have started to win some significant victories. This includes the endorsement of a robust green investment and just transition program in California by the union representing the state’s oil refinery workers.

Of course, these and similar initiatives face relentless opposition from fossil fuel corporations and the full spectrum of interests aligned with them. A clear and coherent global Green New Deal program will serve as one useful tool in the ongoing struggle to save the planet.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).