The French Are Going, But The War In The Sahel Continues

On February 9, 2023, around 100 armed men drove to Dembo, Burkina Faso, on motorcycles and in pickup trucks. They opened fire on a militia group called Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP), which works with the Burkinabé military to protect the areas of northwest Burkina Faso near its border with Mali. These men killed seven members of the VDP. Three days later, on February 12, at the other end of Burkina Faso near the border with Ghana and Togo, armed men entered Yargatenga and killed 12 people, including two VDP fighters. Meanwhile, in another incident that took place from February 9 night until the next day—further north of Burkina Faso near the border with Mali—men on motorcycles arrived at the Sanakadougou village and killed 12 people, burning homes, and looting “the few goods and livestock of the villagers,” reported a survivor to Agence France-Presse. These are not isolated incidents. They have become commonplace in Burkina Faso, where about 40 percent of the country is now largely controlled by a wide range of armed groups who began to target the Sahel after 2012.

Captain Ibrahim Traoré, who leads the Burkinabé government, came to power through a coup d’état in September 2022. He ousted Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, who had himself come to power through a coup in January 2022. Neither of these coups was a surprise. Both followed after the two coups in neighboring Mali (in 2020 and 2021), where the military took over out of frustration with the civilian government’s inability to quell the armed violence. Much of the same dynamics that propelled Mali’s interim President Colonel Assimi Goïta to power pushed Damiba and Traoré to their successive coups. Pressure has been mounting on the military establishment in Mali and Burkina Faso, which are controlled by men in their late 30s and early 40s, to defeat the armed violence that has wracked their region for the past 10 years. Part of the motivation for these coups was the desire to remove the presence of the French military, which intervened in the Sahel region in 2013 to end the violence, but instead—it is widely believed—actively participated in inflaming the violence further. In May 2022, Mali’s Goïta told the French to leave the country, a move repeated by Traoré in January 2023.

Armed Men

When the Algerian civil war (1991-2002) ended, members of the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria (GIA) fled southward and set up bases in Mali, Niger, and southern Libya. Attempts to restart a war by GIA failed, since the Algerian population was exhausted after the decade-long civil war. In 2007, some hardened former elements of the GIA formed Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), which—as I experienced firsthand in the northern Sahel—became an integral part of the trans-Sahara smuggling networks. AQIM members began to work with a group called Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MOJWA), led by Hamada Ould Mohamed El Khairy. Everything changed for these groups with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) war on Libya in 2011, which destroyed the Libyan state and provided Al Qaeda-aligned groups free rein in the region (many of them are now being armed by NATO’s Arab allies in the Gulf). By 2012, AQIM joined hands with many of the Arabs who had been brought to Libya during the war as well as with Tuareg groups from the northern Sahel who had been pursuing their own territorial aims against the government in Mali.

France, which had driven the NATO war against Libya, intervened militarily in Mali to block the rapid movement of these jihadist forces south toward Bamako, Mali’s capital. Operation Serval, the name of the first French mission, pushed these forces out of the major cities of central Mali. Then-French President François Hollande went to Bamako to celebrate these gains in 2013, but said, “the fight is not over.” France established Operation Barkhane thereafter, which expanded through the Sahel region and operated alongside the massive U.S. military presence in the region (which includes one of the world’s largest military bases in Agadez, Niger, not far from France’s garrison at the uranium mine in Arlit, Niger). The inability of France to halt the onrush of these armed groups into the heart of the Sahel has led—largely—to the anti-French sentiment in the region.

Rooted in the Countryside

In March 2017, many of these armed Islamic groups affiliated to Al Qaeda formed the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM), whose leader Iyad Ag Ghali participated in the Tuareg fight against the Malian state (in 1988, he founded the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Azawad). The JNIM rooted itself in the local struggles in the region, capitalizing on the separatist sensibility of the Tuareg people and in the Fulani clashes with the Bambara people of the center of the country. A year after the founding of the JNIM, one of its emirs, Yahya Abu al-Hammam, released a video message that France’s retreat into the cities left the countryside in the hands of the JNIM and its allied forces, who will win “with patience.”

By rooting themselves in the smuggling networks and in the local conflicts over land and resources, the various armed groups affiliated to Al Qaeda made themselves a difficult target. The new governments in Mali and Burkina Faso accuse the French of both bringing these wars into their territory from Libya and exacerbating these conflicts by making deals with the armed groups to prevent attacks on French military bases. Rather than break the insurgency, the French war in the region has resulted in the creation of the Islamic State Sahel Province in March 2022 with the group extending its operations in Burkina Faso’s Oudalan and Seno provinces, Mali’s Gao and Ménaka regions, and Niger’s Tahoua and Tillaberi regions. Now, France departs, leaving behind military governments ill-equipped to deal with what appears to be an unending war.

Russia

In December 2022, Burkina Faso’s Prime Minister Apollinaire Kyélem de Tambèla visited Moscow to apparently seek assistance from Russia in the war against the Al Qaeda insurgency. During his visit, he told RT that he visited the Soviet Union in 1988 and regretted that Russian-Burkinabé relations have weakened. It is likely that more Russian aid will enter these countries, provoking a reaction from the West, but this aid by the Kremlin is unlikely to help the Sahel in breaking away from the entrenched set of conflicts that trouble the region, set in motion under France’s colonial supervision.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

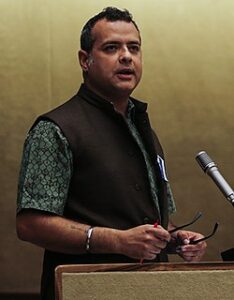

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

Source: Globetrotter

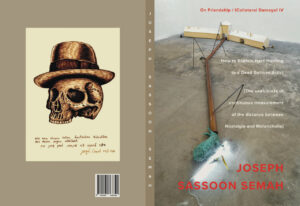

Joseph Sassoon Semah: On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV – How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist

The richly illustrated publication:

Joseph Sassoon Semah: On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV – How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist [The usefulness of continuous measurement of the distance between Nostalgia and Melancholia] will be published in March 2023 on Joseph Beuys and post-war West German art history.

Published by Metropool Internationale Kunstprojecten, final editing: Linda Bouws & Joseph Sassoon Semah, design + layout: kunstburo geert schriever, A4, 208 pages, full colour – ISBN 9789090368399

The publication can now be ordered € 49.95 and € 5 shipping costs: Stichting Metropool Internationale Kunstprojecten, account number NL 42 INGB 0006 9281 68 stating On Friendship IV, name and address.

With contributions from

Joseph Sassoon Semah, Linda Bouws (curator), David de Boer (general practitioner and gallery owner), Albert Groot (psychiatrist), Paul Groot (art historian) Arie Hartog (director Gerhard-Marcks-Haus, Bremen), Bas Marteijn (Chief Country Officer Deutsche Bank Netherlands), Eelco Mes (curator), Markus Netterscheidt (artist), Ton Nijhuis (director Duitsland Instituut/UvA), Hans Peter Riegel (author of the four-volume biography Beuys, Die Biographie), Mati Shemoelof (author), Rick Vercauteren (former director Museum Bommel van Dam, publicist and historian), Andreas Wöhle (President Evangelical Lutheran Synod in the Protestant Church).

Brief description

The publication highlights Beuys’ work and thought from different perspectives and his relationship to post-war culture and politics in particular.

Joseph Sassoon Semah’s (1948, Baghdad) work – drawings, paintings, sculptures, installations, performances and texts – provides ample space for critical reflection on identity, history and tradition and is part of the artist’s long research into the relationship between Judaism and Christianity as sources of Western art and culture and of politics.

Joseph Beuys (1921, Krefeld -1986, Düsseldorf) is one of Germany’s most influential post-war artists, who became particularly famous for his performances, installations, lectures and Fluxus concerts. In 2021/22, Joseph Beuys’ 100th birthday was celebrated extensively with the event ‘Beuys 2021. 100 years’.

But who was Beuys really? Joseph Beuys mythologised his wartime past as a national socialist and Germany’s problematic and post-traumatic past. After WWII, Beuys transformed from perpetrator to victim. How should we interpret Beuys in the future?

Joseph Beuys and Joseph Sassoon Semah, two ex-soldiers, two artists. Joseph Beuys was a former gunner and radio operator in the German air force during WWII; Joseph Sassoon Semah served in the Israeli air force. Who is the (authentic) victim and who is the Victimiser?

Asking The Oppressed To Be Nonviolent Is An Impossible Standard That Ignores History

In January 2023, after five police officers killed Tyre Nichols, President Joe Biden quickly issued a statement calling on protesters to stay nonviolent. “As Americans grieve, the Department of Justice conducts its investigation, and state authorities continue their work, I join Tyre’s family in calling for peaceful protest,” said Biden. “Outrage is understandable, but violence is never acceptable. Violence is destructive and against the law. It has no place in peaceful protests seeking justice.”

In June 2022, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Biden made the same call to protesters. “I call on everyone, no matter how deeply they care about this decision, to keep all protests peaceful. Peaceful, peaceful, peaceful,” Biden said. “No intimidation. Violence is never acceptable. Threats and intimidation are not speech. We must stand against violence in any form, regardless of your rationale.”

It is a curious spectacle to have the head of a state, with all the levers of power, not using that power to solve a problem, but instead offering advice to the powerless about how to protest against him and the broken government system. Biden, however, showed no such reluctance to use those levers of power against protesters. During the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 after the murder of George Floyd, when Biden was a presidential candidate, he made clear what he wanted to happen to those who didn’t heed the call to nonviolence: “We should never let what’s done in a march for equal rights overcome what the reason for the march is. And that’s what these folks are doing. And they should be arrested—found, arrested, and tried.”

In the face of murderous police action, Biden called on protesters to be “peaceful, peaceful, peaceful.” In the face of non-nonviolent protesters, Biden called on police to make sure the protesters were “found, arrested, and tried.”

Are protesters in the United States (and perhaps other countries where U.S. protest culture is particularly strong, like Canada) being held to an impossible standard? In fact, other Western countries don’t seem to make these demands of their protesters—consider Christophe Dettinger, the boxer who punched a group of armored, shielded, and helmeted French riot police until they backed off from beating other protesters during the yellow vest protests in 2019. Dettinger went to jail but became a national hero to some. What would his fate have been in the United States? Most likely, he would have been manhandled on the spot, as graphic footage of U.S. police behavior toward people much smaller and weaker than Dettinger during the 2020 protests would suggest. If he survived the encounter with U.S. police, Dettinger would have faced criticism from within the movement for not using peaceful methods.

There is a paradox here. The United States, the country with nearly 800 military bases across the world, the country that dropped the nuclear bomb on civilian cities, and the country that outspends all its military rivals combined, expects its citizens to adhere to more stringent standards during protests compared to any other country. Staughton and Alice Lynd in the second edition of their book Nonviolence in America, which was released in 1995, wrote that “America has more often been the teacher than the student of the nonviolent ideal.” The Lynds are quoted disapprovingly by anarchist writer Peter Gelderloos in his book How Nonviolence Protects the State, an appeal to nonviolent protesters in the early 2000s who found themselves on the streets with anarchists who didn’t share their commitment to nonviolence. Gelderloos asked for solidarity from the nonviolent activists, begging them not to allow the state to divide the movement into “good protesters” and “bad protesters.” That so-called “antiglobalization” movement faded away in the face of the post-2001 war on terror, so the debate was never really resolved.

For the U.S., the UK, and many of their allies, the debate over political violence goes back perhaps as far as the white pacifists who assured their white brethren, terrified by the Haitian Revolution, which ended in 1804, that abolitionism did not mean encouraging enslaved people to rebel or fight back. While they dreamed of a future without slavery, 19th-century abolitionist pacifists understood, like their countrymen who were the enslavers, that the role of enslaved people was to suffer like good Christians and wait for God’s deliverance rather than to rebel. Although he gradually changed his mind, 19th-century abolitionist and pacifist William Lloyd Garrison initially insisted on nonviolence toward enslavers. Here Garrison is quoted in the late Italian communist Domenico Losurdo’s book Nonviolence: A History Beyond the Myth: “Much as I detest the oppression exercised by the Southern slaveholder, he is a man, sacred before me. He is a man, not to be harmed by my hand nor with my consent.” Besides, he added, “I do not believe that the weapons of liberty ever have been, or ever can be, the weapons of despotism.” As the crisis deepened with the Fugitive Slave Law, Losurdo argued, pacifists like Garrison found it increasingly difficult to call upon enslaved people to turn themselves back to their enslavers without resistance. By 1859, Garrison even found himself unable to condemn abolitionist John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

The moral complexities involved in nonviolence in the antiwar movement were acknowledged by linguist, philosopher, and political activist Noam Chomsky in a 1967 debate with political philosopher Hannah Arendt and others. Chomsky, though an advocate for nonviolence himself in the debate, concluded that nonviolence was ultimately a matter of faith:

“The easiest reaction is to say that all violence is abhorrent, that both sides are guilty, and to stand apart retaining one’s moral purity and condemn them both. This is the easiest response and in this case I think it’s also justified. But, for reasons that are pretty complex, there are real arguments also in favor of the Viet Cong terror, arguments that can’t be lightly dismissed, although I don’t think they’re correct. One argument is that this selective terror—killing certain officials and frightening others—tended to save the population from a much more extreme government terror, the continuing terror that exists when a corrupt official can do things that are within his power in the province that he controls.”

“Then there’s also the second type of argument… which I think can’t be abandoned very lightly. It’s a factual question of whether such an act of violence frees the native from his inferiority complex and permits him to enter into political life. I myself would like to believe that it’s not so. Or at the least, I’d like to believe that nonviolent reaction could achieve the same result. But it’s not very easy to present evidence for this; one can only argue for accepting this view on grounds of faith.”

Several writings have sounded the warning that nonviolence doctrine has caused harm to the oppressed. These include Pacifism as Pathology by Ward Churchill, How Nonviolence Protects the State and The Failure of Nonviolence by Peter Gelderloos, Nonviolence: A History Beyond the Myth by Domenico Losurdo, and the two-part series “Change Agent: Gene Sharp’s Neoliberal Nonviolence” by Marcie Smith.

Even the historic victories of nonviolent struggles had a behind-the-scenes armed element. Recent scholarly work has revisited the history of nonviolence in the U.S. civil rights struggle. Key texts include Lance Hill’s The Deacons for Defense, Akinyele Omowale Umoja’s We Will Shoot Back, and Charles E. Cobb Jr.’s This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed. These histories reveal continuous resistance, including armed self-defense, by Black people in the United States.

Even before these recent histories, we have Robert Williams’s remarkable and brief autobiography written in exile, Negroes With Guns. Williams was expelled from the NAACP for saying in 1959: “We must be willing to kill if necessary. We cannot take these people who do us injustice to the court. … In the future we are going to have to try and convict these people on the spot.” He bitterly noted that while “Nonviolent workshops are springing up throughout Black communities [, n]ot a single one has been established in racist white communities to curb the violence of the Ku Klux Klan.”

As they moved around the rural South for their desegregation campaigns, the nonviolent activists of the civil rights movement often found they had—without their asking—armed protection against overzealous police and racist vigilantes: grannies who sat watch on porches at night with rifles on their laps while the nonviolent activists slept; Deacons for Defense who threatened police with a gun battle if they dared turn water hoses on nonviolent students trying to desegregate a swimming pool. Meanwhile, legislative gains made by the nonviolent movement often included the threat or reality of violent riots. In May 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama, for example, after a nonviolent march was crushed, a riot of 3,000 people followed. Eventually a desegregation pact was won on May 10, 1963. One observer argued that “every day of the riots was worth a year of civil rights demonstrations.”

As Lance Hill argues in The Deacons for Defense:

“In the end, segregation yielded to force as much as it did to moral suasion. Violence in the form of street riots and armed self-defense played a fundamental role in uprooting segregation and economic and political discrimination from 1963 to 1965. Only after the threat of black violence emerged did civil rights legislation move to the forefront of the national agenda.”

Biden’s constant calls for nonviolence by protesters while condoning violence by police are asking for the impossible and the ahistorical. In the crucial moments of U.S. history, nonviolence has always yielded to violence.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

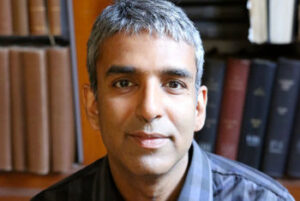

Justin Podur is a Toronto-based writer and a writing fellow at Globetrotter. You can find him on his website at podur.org and on Twitter @justinpodur. He teaches at York University in the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change.

Source: Globetrotter

Chomsky And Prashad: Cuba Is Not A State Sponsor Of Terrorism

Cuba, a country of 11 million people, has been under an illegal embargo by the United States government for over six decades.

Cuba, a country of 11 million people, has been under an illegal embargo by the United States government for over six decades.

Despite this embargo, Cuba’s people have been able to transcend the indignities of hunger, ill health, and illiteracy, all three being social plagues that continue to trouble much of the world.

Due to its innovations in health care delivery, for instance, Cuba has been able to send its medical workers to other countries, including during the pandemic, to provide vital assistance. Cuba exports its medical workers, not terrorism.

In the last days of the Trump administration, the U.S. government returned Cuba to its state sponsors of terrorism list.

This was a vindictive act. Trump said it was because Cuba played host to guerrilla groups from Colombia, which was actually part of Cuba’s role as host of the peace talks.

Cuba played a key role in bringing peace in Colombia, a country that has been wracked by a terrible civil war since 1948 that claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. For two years, the Biden administration has maintained Trump’s vindictive policy, one that punishes Cuba not for terrorism but for the promotion of peace.

Biden can remove Cuba from this list with a stroke of his pen. It’s as simple as that. When he was running for the presidency, Biden said he would even reverse the harsher of Trump’s sanctions. But he has not done so. He must do so now.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter

Noam Chomsky is a linguist, philosopher, and political activist. He is the laureate professor of linguistics at the University of Arizona. His most recent books are Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet and The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

Source: Globetrotter

We’ve Never Been Closer To Nuclear Catastrophe—Who Gains By Ignoring It?

Antiwar and environmental activist Dr. Helen Caldicott warns that policymakers who understate the danger of nuclear weapons don’t have the public’s best interest at heart.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length. A video of the description of nuclear war from the interview can be viewed on Vimeo. Listen to the entire interview, available for streaming on Breaking Green’s website or wherever you get your podcasts. Breaking Green is produced by Global Justice Ecology Project.

This interview took place on January 25, 2023, one day after the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists advanced the hands of the Doomsday Clock to 90 seconds before midnight—in large part due to developments in Ukraine. Dr. Helen Caldicott, an Australian peace activist and environmentalist, discussed the extreme and imminent threat of a nuclear holocaust due to a proxy war between the U.S. and Russia in Ukraine. She also addressed the announcement by the U.S. Department of Energy of a controlled nuclear reaction and outlines the relationship between the nuclear power industry and nuclear weapons.

Caldicott is the author of numerous books and is a recipient of at least 12 honorary doctorates. She was nominated for the Nobel Prize by physicist Linus Pauling and named by the Smithsonian as one of the most influential women of the 20th century. Her public talks describing the horrors of nuclear war from a medical perspective raised the consciousness of a generation.

Caldicott believes that the reality of destroying all of life on the planet has receded from public consciousness, making doomsday more likely. As the title of her recent book states, we are “sleepwalking to Armageddon.”

Steve Taylor: The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists recently set the Doomsday Clock to 90 seconds to midnight. What is the Doomsday Clock, and why is it now set to 90 seconds to midnight?

Helen Caldicott: For the last year, it’s been at 100 seconds to midnight, which is the closest it’s ever been. Each year they reset the clock according to international problems, nuclear problems. Ninety seconds to midnight—I don’t think that is close enough; it’s closer than that. I would put it at 20 seconds to midnight. I think we’re in an extremely invidious position where nuclear war could occur tonight, by accident or by design. It’s very clear to me, actually, that the United States is going to war with Russia. And that means, almost certainly, nuclear war—and that means the end of almost all life on Earth.

ST: Do you see similarities with the 1962 Cuban missile crisis?

HC: Yes. I got to know John F. Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, later in his life. He was in the Oval Office at the time of the Cuban missile crisis. He once told me, “Helen, we came so close to nuclear war—three minutes.” Three minutes. We’re in a similar situation now.

ST: So back then, though, famously, the world held its breath during the missile crisis.

HC: Oh, we were terrified. Terrified, absolutely terrified.

ST: That doesn’t seem to be the case today.

HC: Today, the public and policymakers are not being informed adequately about what this really means—that the consequences would be so bizarre and so horrifying. It’s very funny; New York City put out a video as a hypothetical PSA in July 2022 showing a woman in the street, and it says the bombs are coming, and it’s going to be a nuclear war. It says that what you do is go inside, you don’t stand by the windows, you stand in the center of the room, and you’ll be alright. I mean, it’s absolutely absurd.

ST: That is what you were fighting against back in the ’70s and ’80s—this notion that a nuclear war is survivable.

HC: Yes. There was a U.S. defense official called T.K. Jones who reportedly said, don’t worry; “if there are enough shovels to go around,” we’ll make it. And his plan was if the bombs are coming and they take half an hour to come, you get out the trusty shovel. You dig a hole. You get in the hole. Someone puts two doors on top and then piles on dirt. I mean, they had plans. But the thing about it is that evolution will be destroyed. We may be the only life in the universe. And if you’ve ever looked at the structure of a single cell, or the beauty of the birds or a rose, I mean, what responsibility do we have?

ST: During the Cuban missile crisis, the U.S. did not want missiles pointed at it from Cuba, and the Soviet Union did not want missiles pointed at it from Turkey. Do you see any similarities with the conflict in Ukraine?

HC: Oh, sure. The United States has nuclear weapons in European countries, all ready to go and land on Russia. How do you think Russia feels—a little bit paranoid? Imagine if the Warsaw Pact moved into Canada, all along the northern border of the U.S., and put missiles all along the northern border. What would the U.S. do? She’d probably blow up the planet as she nearly did with the Cuban missile crisis. I mean, it’s so extraordinarily unilateral in the thinking, not putting ourselves in the minds of the Russian people.

ST: Do you feel we’re more at risk of nuclear war now than we were during the Cold War?

HC: Yes. We’re closer to nuclear war than we’ve ever been. And that’s what the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists indicated by moving the clock to 90 seconds to midnight.

ST: Does it seem like political leaders are more cavalier about nuclear exchange now?

HC: Yes, because they haven’t taken in what nuclear war would really mean. And the Pentagon is run by these cavalier folks who are making millions out of selling weapons. Almost the whole of the U.S. budget goes to killing and murder, rather than to health care and education and the children in Yemen, who are millions of them starving. I mean, we’ve got the money to fix everything on Earth, and also to power the world with renewable energy. The money is there. It’s going into killing and murder instead of life.

ST: You mentioned energy. The Department of Energy has announced a so-called fusion breakthrough. What do you think about the claims that fusion may be our energy future?

HC: The technology wasn’t part of an energy experiment. It was part of a nuclear weapons experiment called the Stockpile Stewardship Program. It is inappropriate; it produced an enormous amount of radioactive waste and very little energy. It will never be used to fuel global energy needs for humankind.

ST: Could you tell us a little bit about the history of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, where scientists developed this fusion technology?

HC: The Lawrence Livermore Laboratory was where the first hydrogen bombs were developed. It was set up in 1952, by Edward Teller, a wicked man.

ST: There is this promotion of nuclear energy as a green alternative. Is the nuclear energy industry tied to nuclear weapons?

HC: Of course. In the ’60s, when people were scared stiff of nuclear weapons, there was a Pentagon psychologist who said, look, if we have peaceful nuclear energy, that will alleviate the people’s fear.

ST: At the end of your 1992 book If You Love This Planet, you wrote, “Hope for the Earth lies not with leaders, but in your own heart and soul. If you decide to save the Earth, it will be saved. Each person can be as powerful as the most powerful person who ever lived—and that is you, if you love this planet.” Do you stand by that?

HC: If we acknowledge the horrifying reality that there is an extreme and imminent threat of nuclear war, it’s like being told that as a planet, we have a terminal disease. If we’re scared enough, every one of us can save the planet. But we have to be very powerful and determined.

Author Bio:

Steve Taylor is the press secretary for Global Justice Ecology Project and the host of the podcast Breaking Green. Beginning his environmental work in the 1990s opposing clearcutting in Shawnee National Forest, Taylor was awarded the Leo and Kay Drey Award for Leadership from the Missouri Coalition for the Environment for his work as co-founder of the Times Beach Action Group.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

How Complicit Governments Support The Drug Trade

John P. Ruehl

Several governments or government entities play a double game of enforcing some drug laws while ignoring others. Their reasons vary, and history proves it will be difficult to stop.

The modern globalized world has made it easier and far more lucrative to facilitate and enable international drug networks, and several governments, or elements within them, actively work with criminal groups to support the flow of drugs around the world. This has led to a surge in drug usage among people worldwide, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s World Drug Report 2022, with 284 million people between the ages of 15 and 64 using drugs globally in 2020, which amounts to “a 26 [percent] increase over the previous decade.”

State involvement in the drug trade occurs for a variety of reasons. The allure of profiteering can entice state actors to produce and transport drugs, particularly if their country is under financial duress. Producing drugs or merely taxing drug routes can bring in much-needed funds to balance budgets, create sources of “black cash,” or enrich elites. Allowing the drug trade may also be deemed necessary to ensure regional economic stability and can prevent criminal groups from confronting the state.

In other instances, government agencies and institutions might be “captured” by criminal elements that have gained extreme influence over political, military, and judicial systems through corruption and violence. Government entities also often become too weak or compromised to stop criminal groups, which “have never before managed to acquire the degree of political influence now enjoyed by criminals in a wide range of African, [Eastern] European, and Latin American countries.”

Finally, some governments use the drug trade to promote foreign policy objectives as a form of hybrid warfare. Supporting criminal groups in rival or hostile countries can help challenge the authority of the governments in these states, but it is also an effective way to promote social destabilization. Introducing drugs to other countries fuels local criminal activity, plagues their court and prison systems, induces treatment and rehabilitation costs, and causes immense psychological stress and societal breakdown through addiction.

The Complicity of State Actors in the Drug Trade

The Russian government’s involvement in the international drug trade is due to several reasons. Russian state entities have sought to raise cash for their own benefit but have also historically worked with powerful criminal groups due to corruption and to avoid bloodshed (though the Kremlin has steadily absorbed Russia’s criminal elements under Russian President Vladimir Putin). Additionally, with the West imposing sanctions on the Kremlin after its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Kremlin is seeking to punish some EU countries for supporting Kyiv by bringing drugs into the bloc, leveraging its connections to the Eurasian underworld to do so.

The Kremlin’s role in the drug trade has provided it with influence over former Soviet states in Central Asia, which have also facilitated the drug trade from Afghanistan to Europe for decades. The criminal elements that control this northern route have immense influence over the political and security elites of Central Asian states and rely on cooperation with Russian intelligence services.

Much of the drug trade provides funding for Russian intelligence services, and the Kremlin appears to have approved an increase in drug trafficking in 2022 largely because of the financial difficulties stemming from its invasion of Ukraine.

The Balkans are also a key gateway for drugs entering Europe. In Bulgaria, corruption has seen high-level politicians implicated in drug smuggling, in addition to officials in Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia. The Council of Europe, meanwhile, accused Hashim Thaçi, the former prime minister and president of Kosovo, as well as his political allies, of exerting “violent control over the trade in heroin and other narcotics” “and [occupying] important positions in ‘Kosovo’s mafia-like structures of organized crime’” in 2010. Kosovan politicians continue to face allegations of corruption.

Morocco’s government has largely accepted drug networks to support national economic livelihood, which serves “as the basis of a parallel economy,” while this relationship is reinforced by corruption in the country. Libya had more of a state-backed drug production and export apparatus under former leader Muammar Gaddafi, though this mechanism broke down following the civil war in 2011. However, the close relationship between Guinea-Bissau’s “political-military elites” and drug smugglers has made it Africa’s greatest example of state complicity in aiding international drug networks. The country’s importance in the international drug trade stems from its proximity to Latin America and Guinea-Bissau’s geographic use as a transit stop for criminal groups seeking access to the European market.

In recent years, politicians from Venezuela, Paraguay, Peru, Bolivia, and other Latin American countries have been accused or suspected of aiding and abetting criminals involved in the drug trade. United States officials have also accused former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández and his political allies of “state-sponsored drug trafficking,” as he awaits trial in the United States.

But there has been a decades-long involvement of the United States in the drug trade. In the 1950s, for example, the CIA gave significant support to anti-communist rebel groups involved in the drug trade in the Golden Triangle, where the borders of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar meet. The cooperation lasted into the 1970s, and ongoing corruption in the region means state authorities continue to permit criminal groups a degree of operability.

The CIA also admitted to ignoring reports about Nicaraguan Contra rebels selling drugs in the United States to fund their anti-communist campaign in the 1980s. The United States permitted Afghan farmers to grow opium poppy during the Obama administration’s handling of the War in Afghanistan in 2009 and has been suspected of cultivating Latin America’s drug networks to control the region.

Drug deaths in the United States have, meanwhile, been rising significantly since 2000 and hit record highs during the pandemic, with fentanyl responsible for two-thirds of total deaths. China has been accused by Washington of allowing and enabling domestic criminal groups to import fentanyl into the United States.

While this trade partially diminished after pressure from Washington, fentanyl exports from China now often make their way to Mexico first before crossing the U.S. border. China’s willingness to cooperate with U.S. authorities, as well as authorities in Australia, where Chinese drugs are also imported, has declined as relations between Beijing and Western states have worsened. China’s government is also mildly complicit in the Myanmar government’s far more active and direct role in facilitating the drug trade in Southeast Asia. This is due to Myanmar’s need to both raise funds and control militant groups in the country.

Drug Trade Supporting Economies in Some Countries

Drug production and exporting also give regimes an option for long-term survival. A 2014 report from the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea indicates that after North Korea defaulted on its international debts in 1976, its embassies were encouraged to “‘self-finance’ through ‘drug smuggling.’” In the 1990s, this gave way to state-sponsored drug production to further increase access to foreign currency.

Most of the suspected or arrested drug traffickers from North Korea over the last three decades have been diplomats, military personnel, or business owners. In 2003, Australian authorities busted a North Korean state-sponsored heroin smuggling operation while following Chinese suspects. But by 2004, China was also admitting to problems with North Korean drugs crossing their mutual border. And in 2019, Chinese authorities arrested several people with connections to the North Korean government who were involved in a drug smuggling ring near the border.

The Syrian government has produced and exported drugs for decades. But sanctions and civil war since 2011 have severely weakened Syria’s leadership, prompting it to drastically increase its drug operations to raise funds and maintain power. Exports of Captagon and hashish now generate billions of dollars a year for the Syrian government and far exceed the value of the country’s legal exports.

In neighboring Iran, government officials, as well as state-affiliated groups like Hezbollah, are also complicit in profiting off the drug trade, which also implicates Lebanese officials. Involvement in the drug trade by state-sponsored groups like Hezbollah or Turkey’s Grey Wolves reveal attempts by Tehran and Ankara respectively to make these groups self-sustaining when state support withers.

Overt participation in the drug trade by certain states is likely to continue. Sanctions help fuel the drug trade by making states more inclined to resort to these networks to make up for lost economic opportunities. Additionally, most efforts to combat the drug trade are largely domestic initiatives. Less corrupt law enforcement agencies are often unwilling to work with their counterparts in other countries through forums like Interpol, for fear of their complicity in illegal drug networks. The drug trade also remains a valuable geopolitical tool for states.

Nonetheless, state involvement in the drug trade is a risky venture. It emboldens criminal actors, often involves inviting drugs into national territory, and can result in enormous public backlash. While preventing the involvement of state actors in these practices will be a difficult task, the most overt instances should be scrutinized more thoroughly to ensure these policies are given greater attention.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

John P. Ruehl is an Australian-American journalist living in Washington, D.C. He is a contributing editor to Strategic Policy and a contributor to several other foreign affairs publications. His book, Budget Superpower: How Russia Challenges the West With an Economy Smaller Than Texas’, was published in December 2022.

Source: Globetrotter

- Page 2 of 3

- previous page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- next page