04-03-2024 ~ “Instead of seizing the chance to close schools… communities across the country are pushing their districts to think about schools differently and the possibilities this moment gives us.”

04-03-2024 ~ “Instead of seizing the chance to close schools… communities across the country are pushing their districts to think about schools differently and the possibilities this moment gives us.”

Judging by a rash of news reports beginning in late 2023, communities across the country may be gearing up for a massive wave of school closures in 2024. “A school closure cliff is coming,” warned an article in the Hechinger Report in August 2023. The headline of a January 2024 article in the 74 read, “Exclusive Data: Thousands of Schools at Risk of Closing Due to Enrollment Loss.” Also in January, an article in Education Week with the headline, “Pressure to Close Schools Is Ramping Up. What Districts Need to Know,” highlighted potential or confirmed closures in Boston, Memphis, Tennessee, Wichita, Kansas, Jackson, Mississippi, Missouri, and Indiana.

The standard narrative in these reports is that the COVID-19 pandemic pushed families into online learning in 2020 and emptied school buildings. This was such a massive disruption that parents turned to alternative education options such as charter schools, private schools, microschools, and homeschooling. That transfer of students, along with the drying up of emergency relief funds that the federal government gave to schools to address the impact of the pandemic, have stressed state and local education budgets to the point of having to cut costs, including closing school buildings.

Both education reporters and policy experts tend to frame stories about school closures as “difficult” but “inevitable.” Justifications for closures are steeped in the language of business and economics with words like “efficiency” and “rightsizing” dominating the discourse. District leaders tend to be portrayed as pragmatic realists doing what’s best for children, while efforts to include parents and teachers in decisions over how many schools to close and where are often cast as “placating the adults.”

At the end of the typically torturous process of closing schools almost no one is pleased, especially in low-income Black and brown communities where closures most often occur.

Students, both those whose schools were closed and those in schools receiving an influx of students from the closed schools, are often negatively impacted by closures. And numerous studies about school closures for financial reasons have found that the promised savings from closing school buildings generally never materialize.

Because of the mostly negative results of closing schools, educators and public school advocates that Our Schools recently spoke with want school and policy leaders to rethink why and how they decide to close schools.

Many question the narrative about the need to close schools. They call for district and policy leaders to take steps to ensure families and community members are more involved in closure decisions. They also believe that school district leaders should be more proactive in avoiding school closures by implementing policies and programs that are more likely to attract and hold onto families.

Moreover, school closure skeptics are calling for policy leaders to change their thinking about schools and to regard them as permanent community assets rather than fleeting enterprises that come and go. Their strategy of choice for transitioning to an education system with long-term sustainability is for districts to adopt what’s called the community schools approach.

It’s a big ask, but one that might be perfectly positioned for a moment when policy leaders and government officials are faced with decisions over how to ensure every student has access to a high-quality neighborhood school.

‘An Absolute Failure of Leadership’

“School closures are an absolute failure of leadership,” said Cecily Myart-Cruz, “especially when the closures are in the most marginalized areas of the district.” Myart-Cruz is president of United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA), the main representative organization for educators and school staff in the Los Angeles Unified School District, where talk of closing schools has been ramping up.

“The question that should be asked is how did [district leaders] let things get to this point?” she said.

“We don’t believe that school closures are inevitable,” said Moira Kaleida, the director of the Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools (AROS), a coalition of labor organizations, policy shops, and grassroots groups that advocate for public schools. Her organization is working with community groups in Pittsburgh, where the district is considering a plan to close and consolidate schools.

“We know that in the past, the schools that have been closed were those in Black and brown neighborhoods, or rapidly gentrifying areas—to be converted to condos,” she said. “We have been demanding a seat at the table.”

“Texas schools are being hit by a perfect storm of financial disinvestment from the state and student transfers to charter schools,” said Patti Everitt, a consultant who works with school districts and pro-public education organizations, including the Texas chapter of the American Federation of Teachers.

School districts across the Lone Star State have announced or are actively discussing school closures for a variety of reasons, including enrollment declines and loss of students to charter schools.

“When districts realize the losses due to charters, they propose closing local neighborhood schools which infuriates parents,” Everitt said. “Closures are a big problem for parents, and district officials will always get the blame rather than state officials or charter companies.”

“Districts that start closing schools may very well find they are acting in haste,” warned Carol Burris, the executive director of the Network for Public Education, a national group that is pro-public schools. “Homeschoolers will trickle back, and more immigrants are arriving. It is the public school that will take care of them,” she said.

What the Data Says

Public school advocates are skeptical of the media narrative about the need to close schools. They point to data from the U.S. Census Bureau showing that enrollments nationwide rebounded to pre-pandemic levels in 2022; although, they still remain lower than the 2018 levels.

Also, enrollment trends are uneven depending on grade level, as Education Week reported, as there have been increasing enrollments of older students, while enrollments have fallen in younger grades.

And, the idea that falling enrollments are mainly due to parents choosing to homeschool their children or sending them to privately operated schools is questionable.

Since schools have reopened after the worst years of the pandemic, charter enrollments have been “flat,” Chalkbeat reported. “Private school enrollment has remained level,” Burris noted, pointing to government data.

Burris acknowledged that there was a “surge in charter enrollment” due to the pandemic but attributed a lot of that surge to the explosive growth of enrollment in online charters, especially during the worst years of the pandemic. However, these online schools often have higher rates of student attrition than brick and mortar schools, and families leaving them will likely need the public system to fall back on.

“What has increased since the pandemic is homeschooling,” Burris said.

Indeed, a 2023 study by the Urban Institute found that “between the 2019–20 and the 2021–22 school years, homeschool enrollment increased by 30 percent.” But more than a third of students who are missing from public school enrollments are missing from the education system altogether. Are they homeschooling or “no schooling,” said Burris, during her interview.

Indeed, some of the “trickle back” Burris predicted has been happening. According to a March 2024 Brookings study, in the 2022-2023 school year, “traditional public schools gained back one out of 5 percentage points in the share school-age children they lost between 2019–20 and 2021–22.”

While the Brookings analysis found enrollment gains in the public sector during 2022-2023 are “not uniform,” especially when declines among rural schools are accounted for, it concluded that “The dwindling student counts in some schools signal opportunities to strengthen community and school supports.”

‘A False Narrative’

Because of these uncertainties over enrollment trends and the impact privately operated schools have on them, public school advocates are wondering if current calls for school closures are efforts to advance hidden agendas.

“As soon as there is any inkling of a conversation about enrollment declines, district leadership will present closures as the only solution,” said Myart-Cruz. “They’ll say that what’s causing closures is something they have no control over. But that’s a false narrative,” she said.

“Those who oppose public education are seizing the opportunity [provided by] the pandemic as a chance to further dismantle it,” said Kaleida. “This is just another repeat of the same plays we see every 10 years—San Antonio, Jackson, Mississippi, and Pittsburgh—where they are using an almost identical plan from their last attempt to close [public] schools.”

In the many school districts where Everitt has worked, she has noticed a recurring pattern in which school leaders who were grappling with enrollment and demographic changes, which strain school budgets, brought in outside consultants specializing in helping districts navigate the school closure process.

Armed with a consultant-authored report, which predictably recommends closing schools, district leaders present closures as a forgone conclusion and limit discussions to deciding which schools, listed by the consultant, to close.

This strategy effectively fractures any opposition to the closure plan, as parents, frontline educators, and public school advocates find themselves arguing about how to whittle down the list of possible closures rather than challenging the need to close any schools at all. Invariably, schools where parents and teachers are better organized and empowered are more likely to get taken off the list while schools with the most marginalized families end up on the chopping block.

Educators and public school advocates want that practice to end and want to broaden discussions to questions about how to create a system in which schools are more sustainable and adept at acclimating to the changing needs of their surrounding communities.

An Alternative to a Market-Based Approach

“Instead of seizing the chance to close schools,” Kaleida said, “communities across the country are pushing their districts to think about schools differently and the possibilities this moment gives us.”

One such possibility that educators and public schools advocates want to see coming out of the dialogue over school closures is for more districts to adopt an increasingly popular approach to school operations called community schools.

In the community schools approach, schools are treated as essential hubs in the community for student and family services that go beyond academics, including taking care of their physical and mental health, nutrition, afterschool care, and career education.

Inherent in the community schools approach is a reliance on collaborative leadership that includes a wider circle of stakeholders in the school to determine policies and programs.

The community schools idea is a significant departure from what is called—by both critics and proponents—a market-based approach that has been in vogue for the last two decades or more. A market-based approach assumes that schools should operate more like businesses, competing for resources and “customers,” and they should open and close based on market conditions.

The thinking is that when schools experience market conditions that constrain their financials—because, for example, the surrounding neighborhood’s demographics change, or parents choose to send their children to the private sector—the ones that exhibit the most financial difficulties should close and the more adaptable schools should survive.

In contrast, the community schools approach considers schools to be essential infrastructure that communities rely on—much like they depend on parks, libraries, sanitation services, public works, and fire and police protection. And any consideration to closing a school would be determined through a democratic process with consideration of the multiple impacts that such closures would have on families and the community.

‘Public Schools Belong to the People’

One place where this clash in the community schools approach is challenging the entrenched market-based ideology is the San Antonio Independent School District. A proposal by the district administration to “rightsize” the district by shuttering 15 schools and shrinking the district’s building capacity by more than 15 percent was approved in November 2023 by the district board of trustees.

Shortly after the district’s plans for closing schools came to light, groups representing teachers, school staff, parents, students, and public school advocates formed the Schools Our Students Deserve Coalition in June 2023 to challenge what they called a “rushed” decision-making process and what they saw as the lack of community engagement in the closure plan.

“We knew a plan that would include school closures was coming down the pike,” said Alejandra Lopez in an interview with Our Schools. Lopez is a school teacher and president of the San Antonio Alliance of Teachers and Support Personnel, the elected employee union in the San Antonio Independent School District. She also leads the Schools Our Students Deserve Coalition.

“Other districts around us have closed schools,” Lopez said. “We knew the central office’s perspective was to favor school closures. We knew most board members already had their minds made up to close schools. Our superintendent, who was hired in 2022, had been here for less than a year when he announced the rightsizing effort. He had previously served in Denver, Los Angeles, and Rochester [New York], which are all districts that follow the portfolio model. San Antonio also follows the portfolio model.”

The portfolio model Lopez is referring to is an example of a market-based approach to school operations that relies heavily on an influx of charter schools. The basic idea is that school boards should invite competition from charters into the district and treat schools as if they were individual investments in a stock portfolio. Board members should be agnostic about who runs individual schools, and the role of the elected board becomes more about tracking the performance of each school, based on test scores, and closing schools—similar to selling off underperforming stocks—at the bottom or turning them over to other private contractors.

But rather than digging in and opposing closures outright, Lopez and her allies favor a more nuanced approach in which they focus their opposition on what she described as a top-down process driven by the administration that did not adequately consider the voices of students, parents, teachers, and others in the community.

“We acknowledged the need to close schools,” Lopez said, referring to the district’s plans to shut schools that her organization held negotiations for. “We were more interested in attending to what community members wanted.”

What community members want, according to Lopez, is to have more control over which schools close and why.

“Our district has done better than most,” she said, “but it still came to the community with a list of schools to close rather than discussing with the community the factors that would put schools on the list.”

In a November 2023 letter supporting the Schools Our Students Deserve Coalition’s call for the district board of trustees to vote no on the rightsizing plan, the Advancement Project, a civil rights organization that is pro-public schools, accused the district administration of ignoring the coalition’s demands, following “the advice of school privatization consultants who have an agenda to close schools,” and building the case for closure on “redundant metrics” that created “a veneer of objectivity” to justify an “agenda and foregone conclusion to close schools.”

“Each community should be allowed to vote on a closure plan. Public schools belong to the people and people should get to decide,” Lopez said. And her coalition wants the metrics for school success to come from students, parents, and school staff perspectives and not just from the central office.

She and her allies also want a community-wide dialogue about how school leaders are prepared to address the negative effects of closures; how closures will affect class size, teacher planning time, and graduation rates; and what will happen to the shuttered buildings.

Lopez and her coalition members have also pushed for the district to adopt the community schools approach.

“Our coalition believes that adopting a community schools model would both ensure that our schools are meeting the needs of our students and communities in the aftermath of closures and would mitigate what the research says are some of the negative consequences of closure. Plus, we also believe that a community schools model would attract more students to our district.”

‘A Great Solution’

Another advantage of the community schools approach is that it helps build a system of structures into the school administration—such as governance committees, assessments, and decision-making processes—that resist reform fads and the pet projects of school leaders who often use their tenures to job hop their way to evermore prestigious positions.

For example, Everitt described a situation in Austin, Texas, in which a coalition she helped organize had formed to counter district proposals to close a high school for academic underperformance. The coalition’s effort successfully staved off the closure for a number of years, but it took an incredible commitment from parent organizers and volunteers who routinely showed up at public meetings, brought in experts to critique the district’s plans, and worked doggedly to gain strategic access to district leaders.

But because the resistance to closure relied on the strength and stamina of individuals rather than a more resilient system of governance, it proved to be unsustainable, and when the district’s superintendent departed, and a new leader who had other interests came in, the work the coalition had managed to achieve was thrown out, and the closure process restarted.

“The community schools approach is a great solution for giving parents what they want,” Everitt said, yet she conceded that the approach’s success is reliant on district leaders having access to sustainable resources and a willingness to reach out to parents and community and use the results of the outreach to shape policy.

“Most parents and community members just don’t know the assets of their local public schools,” she said.

‘What Is Our Marketing Plan?’

“Community schools are the transformation we need,” said Myart-Cruz.

She acknowledged that Los Angeles schools face a challenging terrain that includes an aging city population, declining birth rates, and market competition from charter schools, all while dealing with the lingering impact of pandemic disruptions. But rather than responding to those challenges by closing schools in the most marginalized communities, she argued that district leaders need to take a lesson from charter schools and develop a plan for attracting parents back to district schools using the promise of the community schools approach.

“District leaders should ask themselves, ‘Are we being effective marketers to bring back families who’ve left and keep the families we have? What will hold families and foster a sense of belonging in a loving and safe space?’”

As evidence that the community schools model can be an effective strategy to woo back families to public schools, she pointed to the resurgence of Baldwin Hills Elementary School.

The school had experienced significant enrollment declines, so much so that the district determined Baldwin’s building was underutilized and decided to colocate a charter school there in 2016. The charter colocation led to more parents leaving the school when space that had been used for a computer lab, a yoga room, an orchestra program, and special education services, was taken over by the charter, according to KCRW.

But after the school adopted the community schools idea, enrollment rebounded, according to Myart-Cruz.

In the 2021-2022 school year, when Baldwin started its first year of the community schools implementation, it had 391 in attendance, according to district records. By 2023-2024, attendance levels had risen to 433, justifying the school’s demand to reclaim some of its lost space from the charter, which prompted the charter management company to leave the building for another location in the fall of 2023.

Another school, Miramonte Elementary, which had experienced significant enrollment declines in the wake of a horrendous sexual abuse scandal, also experienced an attendance rebound after implementing the community schools approach in 2021. According to district data, the number of students attending the school increased from 639 students in 2021-2022 to 683 in 2023-2024.

“Charters know they have to market to survive,” said Everitt, noting that an independent audit of the IDEA charter management company in Texas found the organization’s advertising budget was more than $15 million annually, as of June 2022.

“When charters want to increase enrollment they have a marketing plan,” said Lopez. “What is our marketing plan? If the main issue is enrollment declines, then there’s never been a better opportunity for the community to come together to create a plan to boost enrollment and to empower public school parents to voice their support for the public schools they want.”

By Jeff Bryant

Author Bio: This article was produced by Our Schools.

Jeff Bryant is a writing fellow and chief correspondent for Our Schools. He is a communications consultant, freelance writer, advocacy journalist, and director of the Education Opportunity Network, a strategy and messaging center for progressive education policy. His award-winning commentary and reporting routinely appear in prominent online news outlets, and he speaks frequently at national events about public education policy. Follow him on Twitter @jeffbcdm.

Source: Our Schools

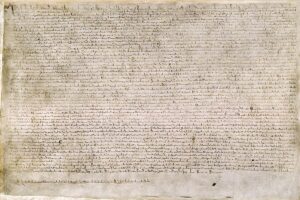

04-03-2024 ~ Political polarization—the inability of groups such as political parties, religious sects, and cultural identity groups to cooperate even in basic, essential matters—has been a worry and a threat since American democracy began, and for many centuries before. James Madison called it “faction,” and in The Federalist, No. 10, he

04-03-2024 ~ Political polarization—the inability of groups such as political parties, religious sects, and cultural identity groups to cooperate even in basic, essential matters—has been a worry and a threat since American democracy began, and for many centuries before. James Madison called it “faction,” and in The Federalist, No. 10, he  04-03-2024 ~ “Instead of seizing the chance to close schools… communities across the country are pushing their districts to think about schools differently and the possibilities this moment gives us.”

04-03-2024 ~ “Instead of seizing the chance to close schools… communities across the country are pushing their districts to think about schools differently and the possibilities this moment gives us.”

03-31-2024 ~ Thailand’s lower house endorses historic same-sex marriage bill, paving the way for southeast Asia’s first marriage equality law amid evolving LGBTQ+ rights landscape.

03-31-2024 ~ Thailand’s lower house endorses historic same-sex marriage bill, paving the way for southeast Asia’s first marriage equality law amid evolving LGBTQ+ rights landscape.