Chapter 4: A Land Of Opportunity And Challenge ~ Irish Investment In China. Setting New Patterns

Introduction

Introduction

Li and Li (1999: 11) contend that ‘for potential foreign investors, a omprehensive understanding of the investment environment in China – including its unique history, culture, political system, socio-economic regime, legal system, infrastructure, and consumer behaviour is essential for the establishment of successful ventures in China’.

This paper will draw together the data generated by this research and identify the locational advantages and disadvantages which China holds for Irish investors. Initially the locational advantage which China offers will be considered as a means of appreciating the opportunity which China offers Irish investors.

This will be followed by a consideration of the locational disadvantages which China poses in the areas identified in the literature and through this research, namely the regulatory, cultural and legal frameworks. The literature review identified the legal framework as challenging, so issues raised in this research, namely contract law and intellectual property rights, will be considered.

Finally the effects of regionalism will be discussed with both locational advantages and disadvantages identified. At the conclusion of this paper we will be in a position to answer the question posed in the sub-hypothesis as to whether or not the business environment in China is different from that experienced by Irish investors in other markets. If this is the case, this analysis will also assist in providing an answer to our prescriptive research question as to the desirability of state involvement in the facilitation of Irish FDI into China.

Locational Advantages which China offers

The literature review points to the considerable advances which China has made in attracting inward FDI since the opening-up policy was introduced in 1979. MNEs continue to recognise the locational advantage which China offers and are seeking to exploit their ownership and internalisation advantages by investing in China.

China’s overall record since reforms began in 1979 is dazzling, and its performance is in many ways improving. Annual real GDP has grown about 9% a year, on average, since 1978 – an aggregate increase of some 700%. Foreign trade growth has averaged nearly 15% over the same period, or more than 2,700% in aggregate. Foreign direct investment has flooded into the country, especially throughout the past decade… The country has developed a powerful combination – a disciplined low-cost labor force; a large cadre of technical personnel; tax and other incentives to attract investment; and infrastructure sufficient to support efficient manufacturing operations and exports. (Lieberthal and Lieberthal, 2004: 3-4)

Associated with this rapid economic growth is an ever-increasing domestic consumer market. ‘Host countries with larger market size, faster economic growth and higher degree of economic development will provide more and better opportunities for industries to exploit their ownership advantages and therefore, will attract more market-oriented FDI’. (OECD, 2000: 11) ‘Survey evidence suggests that the main motives for Irish companies investing abroad are to enter new foreign markets and acquire new technologies rather than to

lower the cost base’. (Forfás, 2001: 4) This view is supported by this research, with the vast majority of executives clearly identifying the locational advantage which China offers as market opportunity. This research among both Irish and non-Irish MNEs also supports the views of Li and Li (1999), who argue that MNEs from developed economies which invest in China will be attracted by the large and growing consumer market and the significant potential for future development rather than the relatively cheap labour pool which China also offers. We can say therefore that the size and growth of the Chinese economy has been identified by Irish investors as offering a significant locational advantage, within the meaning of Dunning’s eclectic paradigm model.

While China has a population of 1.3 billion, the literature indicates that the consumer market is primarily along the eastern seaboard and numbers in the region of 300-350 million. This research supports this finding. This is equivalent to the population of the European Union before the ten central and eastern states joined in 2004. A market of this size in one country, greater than the domestic market of the US, represents a considerable locational advantage. While China’s eastern seaboard does not obviously have the purchasing power to be found in developed economies, the consumer market is segmented and growing rapidly. China’s upper middle class is not dissimilar to the size of Germany’s population, with GDP continuing to grow at close to double digit levels. In this environment of continuing high economic growth and increasing consumer spending power, foreign MNEs see the attractiveness of investing in China. Lieberthal and Lieberthal (2004: 4) give an indication of the magnitude of the locational advantage available to investors in China.

Four to six million new cell phone subscribers are signing up every month. Computer use is spreading more rapidly than in any other country. The automotive market is surging, making China the one place in the coming decade where carmakers can compete for a pie that is growing rather than fight over one that is not. In the early 1990s, almost all retail outlets in China were small shops and wet markets. Now, at least in major cities, hypermarkets are common… Long-term trends in China, moreover, promise continued growth.

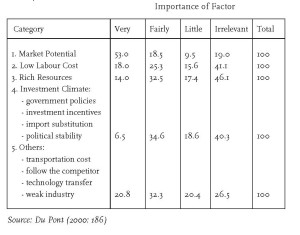

The findings of this research support an attitudinal study undertaken among foreign investors in China by Du Pont (2000). In a survey of 100 investors in China, each firm with an investment in excess of USD1 million[i],Du Pont (2000) found market potential to be the prime motivator driving FDI.

Some interesting data emerges from Du Pont’s study. There is a clear identification among investors of the market potential which China offers. Over half of those surveyed (the highest result for any category) identify market potential as ‘very important’. This is clearly corroborated by our research findings. Slightly over half see little or no importance in low labour costs. Again, Du Pont’s study is supported by this research. Rich resources emerged as relatively important in Du Pont’s study but this is not surprising given that the car and cement industries were included. In Du Pont’s research, over half see government policies and incentives as of little or no importance. This would seem to indicate that those surveyed are broadly content with the political environment and level of incentives available.

A second reason why MNEs from developed economies are investing, and identified by this research, is that as more MNEs invest, MNEs which have supply contracts with the initial investor must also invest in China in order to protect their supply contracts. This was identified by both Irish and non-Irish MNEs. This phenomenon appears to be particularly prevalent in the electronics industry and is likely to increase in importance in China for two reasons. Firstly, large electronics manufacturers want to gain an increasing share of the domestic Chinese market.[ii]Secondly, as more and more firms locate, a critical mass is created, which means that other MNEs in this sector have little

choice but to follow. This reason was cited by an Irish MNE which operates in the electronics sector.

China also offers other locational advantages. The OECD (2004) has identified the considerable resources which China has committed to the development of its physical, financial and technological infrastructure, which has resulted in a higher standard than that in many of China’s east and south-east Asian competitors. In addition, since China acceded to the WTO it has sought to display an openness to international trade and access to its markets. This is exemplified by the reduction in ‘the average level of applied import tariffs from more than 50% in 1982 to just under 10% in 2005. Compared to many developing countries, China’s average import tariff is relatively low’. (Bergsten et al, 2006: 81) While the removal of barriers to trade can remove one of the incentives to invest, countries which are more open to trade tend to receive higher levels of inward FDI. (Lipsey, 2000)

Some commentators cite the relatively low cost and productivity of labour as a key locational advantage which China offers. (Although, as indicated earlier, there are significant regional variations in this regard. If an investor wishes to avail of low labour costs, then the centre and western parts of the country are more appropriate then the eastern seaboard.) As a reason for investing, this is not particularly relevant for Irish investors, with only 10% of Irish MNEs citing this locational advantage as a key determinant. Low labour costs are an important consideration for investments from some countries, but not those from Ireland.

The executives who participated in this research referred to the level of incentives available. However, these incentives did not feature prominently in the decision to invest. What was evident was the need for MNEs to locate in a Special Economic Zone to benefit from preferential tax treatment. Also, investing MNEs should be cognisant of the significant inter-regional competition to attract inward FDI. In particular, MNEs in hi-tech industries are likely to receive offers of attractive incentives. Generous land-use permits are one of the most important fiscal incentives available to local authorities. All land is owned by the State and land-use permits grant a 50-year lease in the case of an enterprise or a 70-year lease in the case of a private dwelling. The Detailed Implementation Act of the Equity Joint Venture Law provides that provincial level governments have the power to determine the scale of rent for land-use fees.

Foreign investments are entitled to tax exemptions and reductions e.g. there are tax exemptions for profits for the first two years; 50% reduction for the next three years; and an additional ten years of 15-30% tax reduction for those located in economically deprived areas. The average tax rate for foreign investments is typically of the order of 15%, while indigenous enterprises face a rate of 33%. However, in order to comply with its WTO obligations on non-discrimination, in March 2007 the National People’s Congress announced that corporation tax for all entities, both foreign and domestic, will be amended to 25% for new investments. However, tax breaks will still be permitted in Special

Economic Zones. This movement in rates appears to have done little to dampen inward investment. Presumably this is because the economy’s large-scale inward FDI, coupled with the country’s substantial trade balance, has created excess liquidity in the economy.

As the focus of Irish investment into China is the exploitation of market opportunity, changes in the tax code are unlikely to significantly affect the levels of Irish inward FDI. This research found that executives did not place particular emphasis on taxation policies in their decision to invest. This supports the relevant literature, which found that taxation is part of a package of measures which investors find attractive (Moosa, 2002; Agarwal, 1980) and shows that incentives are considered as part of the risk and return considerations. If changes in tax codes are to affect inward FDI, it is likely to be in those industries where low-cost labour rates are the motivating factor behind the FDI. In the case of China, this type of FDI originates mainly in east and south-east Asia.

Overall, Irish MNEs which have invested in China to date conform to Li and Li’s (1999) categorisation of investment by MNEs from developed economies. They also conform to the general trend in Irish outward FDI, which focuses on market opportunity. (O’Toole, 2007) While accepting the limited nature of this study, it is interesting to note that no significant motivational variations between Irish and non-Irish MNEs included in this research have been found, a fact which lends weight to the view that Irish investment in China appears to conform with investment patterns from other developed economies.

Locational Disadvantages which China Poses

The Regulatory Framework

Luo (2000) contends that the peculiarity of China’s economic system generates uncertainties for international firms that operate there. The OECD (2005) calls for significant reforms in public and corporate governance, observing that laws and regulations are sometimes applied in an unsystematic manner and can be skewed by special interests.

It is important to be aware of the developing nature of the Chinese economy and the relatively recent creation of the framework governing FDI. China has put in place a legal and regulatory infrastructure in a relatively short space of time, with institution building starting only in 1979. The Law on Joint Ventures Using Chinese and Foreign Investment, which is also known as the Equity Joint Venture Law, was promulgated in July 1979. This legislation is brief and contains only 15 articles. Since it was sketchy and its wording was vague, it left latitude for divergent interpretations and a lack of legal certainty. Many important operational issues, such as market access, taxation, foreign exchange and land use, were not dealt with or were defined in ambiguous terms. This allowed provincial governments to interpret the law and laid the foundation for the strong inter-provincial competition to attract inward FDI which still exists today. In addition, the name of the Equity Joint Venture Law spells out the investment model permitted in the early stages i.e. only joint ventures between a foreign investor and a Chinese partner.

Between 1984 and 1990 the three most important elements of the enlarged legal framework were the Provisions for the Encouragement of Foreign Investment, the Law on Wholly Foreign-owned Enterprises (the WFOE Law) and the Law on Cooperative Joint Ventures (the CJV Law). The permitted movement from Joint Venture companies to Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprises (WFOE) is significant. Executives included in this research indicated a strong preference for a WFOE structure rather than a joint venture arrangement. These findings are supported by the views of Shenkar (1990) and Teagarden and Von Glinow (1990), both of whom express a high level of performance difficulties in joint venture arrangements. In this study there was a perception that the Joint Venture arrangement existed to serve the requirements of the Chinese partner first and the foreign investor second.

Depending on the size and location of the FDI project, the foreign investor must approach the relevant authorisation agency. China has a three-tiered structure for approval of FDI projects: the central government, provincial governments, and county governments, depending on the size of the financial investment. The State Council (the central government level) has the authority to approve projects above USD 100 million. The State Planning Commission and Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation (MOFTEC) have the authority to decide on FDI projects between USD 30 million and USD 100 million. Provincial governments have the authority to approve projects up to and including USD 30 million; local government (the county level) has the authority to decide on projects below USD 10 million. The OECD (2003: 19) has called for a ‘raising of [the] FDI project value limit above which approval has to be submitted to central government departments at national level and increasing the approval powers of local governments accordingly’.

In the evaluation procedure, relevant government agencies have the duty to examine whether the capital subscribed to the project has been assured; whether the proposed project does not require additional allocation of raw materials by the State; and whether the project does not adversely affect the national balance of fuel, power, transportation and export quotas (Implementing Regulations on the EJVL, art 8(1) and (2)). FDI projects are required to promote and benefit the development of China’s economy (Implementing Regulations on the EJVL, art 3 and WFOEL, art 3). These requirements indicate the added-value dimension which the Chinese Government requires of foreign investments i.e. that they should bring in advanced technology and equipment or generate foreign currency. It is important for Irish investors to be aware of such regulations as foreign investors are required to set out how they comply with these requirements.

Executives of non-Irish MNEs found the business licence process to be bureaucratic but manageable. Irish investors found the process more challenging, which is understandable given the lack of such requirements in Ireland. Interviewees referred to particular sectoral licensing issues. It can be expected that China will continue to liberalise the investment regime as it continues to meet its WTO obligations. Unless there are issues relating to national security, or the continuity of supply, or there is a natural monopoly, it is difficult to justify sectoral restrictions on FDI. A role exists for state involvement in lobbying for the removal of such restrictions because ‘government restrictions on who can do business in which sectors were specifically designed to protect domestic producers from international competition’. (Breslin, 2005: 739)

A regulatory restriction is in place on the availability of capital, but it has to be acknowledged that this is constantly evolving. Local banking systems and equity

markets are underdeveloped in China and venture capital is particularly limited. (Khanna, 2005) Foreign currency restrictions were also an issue raised during this research. While China has made moves to liberalise its currency, it is not a freely convertible currency. Investors can repatriate profits but only with the consent of the State Administration for Foreign Exchange. This consent is granted provided one’s tax affairs are in order, but delays can be experienced.

Investors should also be aware of particular requirements relating to the transfer of technology. Given the predominantly hi-tech nature of Irish industry,such requirements are of relevance. Borensztein et al (1995) developed a crosscountry regression framework for testing the effect of FDI on economic growth by drawing on investment flow data from industrialised economies to sixty-nine developing economies over a twenty-year period. Their results show that FDI is an important vehicle for the transfer of technology from developed to developing countries. The effects of the conclusion reached by Borensztein et al are evident in the Chinese Government’s focus on seeking a transfer of technology when investors are negotiating inward FDI. A potential spin-off of this is an upgrading of local industry. In addition to the transfer of technology, there is an expectation that the transfer will lead to an increase in social capital skills. The effect of this policy was made clear by the executive of the automotive MNE, which had in effect to double its anticipated level of investment by installing the most up-to-date technology in its manufacturing plant. The requirement to affect a transfer of technology can have adverse implications for an MNE’s ownership advantage if sufficient precautions are not taken to protect intellectual property rights. (See below for a discussion of this issue.)

In summary, the regulatory regime can be described as complex but by no means impossible to deal with and, as such, cannot be described as a significant locational disadvantage. However, as will be argued below, the regulatory requirements regarding the transfer of technology combined with the lack of protection for intellectual property rights represents a potential threat to an MNE’s ownership advantage.

China’s Culture

Culture can be a form of location-specific disadvantage within the context of Dunning’s eclectic paradigm and has the potential to dissipate other location specific advantages. While China is in rapid economic transition, it still has a strong cultural heritage. ‘Although the history of China has been marked by periodic upheavals, its majority of Han people have experienced the longest span of homogenous cultural development of any society in the world… Since the Chinese culture and social structure are very different from the western world, it is essential for potential investors in China to develop a comprehensive understanding of these differences’. (Li and Li, 1999: 130)

With China’s 5,000 years of civilization history, Chinese culture, tradition, and its value system have a significant impact on the operations of all Chinese businesses, as well as on joint ventures. (Yin and Stoianoff, 2004) Li et al (2001) argue that foreign investors can encounter problems not only of an institutional nature but also informal constraints such as culture and ideology. In this regard Yin and Stoianoff (2004) contend that an understanding of Chinese social and cultural background is necessary for foreign investors because it can help them to handle the differences in Chinese society. The core of Chinese culture is directly related to Confucianism[iii]and the key traits of Chinese culture emphasise relationships, face saving, and reliance on the group. Although formal laws and regulations have always existed in traditional Chinese society, they could be amended to favour people in different situations. In order to obtain such a favourable amendment, Chinese culture has formed a special institutionalised system of personal relationships called guanxi. Traditionally, guanxi was used as an alternative path to formal bureaucratic processes and procedures. Guanxi operates both within and outside the official economy and involves the cultivation of personal networks of mutual dependence and trust. (Yang, 1986; Smart, 1993)

China’s cultural uniqueness and the role of guanxi were exploited in the early phase of the reform process, when much of the FDI came from countries or regions that have large overseas Chinese populations, notably Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Singapore. This wave of FDI was focused on the Pearl River Delta (the hinterland surrounding Hong Kong) and Xiamen. A strategic decision was taken to exploit this relationship.

‘[T]he predominance of Hong Kong investment in China may be largely due to use of guanxi and the dramatic reduction in costs that it facilitates (Smart and Smart, 1991)’. (Jones, 1994: 201) Overseas Chinese from Hong Kong and Macao have a similar dialect and culture similar to those to be found in the Guangdong Province. Jones (1994) points to a general cultural preference for relational rather than formal legal and impersonal ties, which is shared by both mainland and overseas Chinese, and which has practical economic effects.

[T]he Chinese economy is still characterised by undeveloped market structures, poorly specified property rights and a weak production market. In this situation, the guanxi network often substitutes for government instituted, formal channels of resource allocation and dispersal. (Luo, 1998: 173)

Davies et al (1995) point to the importance of business networks, arguing that they enhance comparative advantage by providing access to the resources of other network members and are particularly important in respect of market entry. This research found that the executives of MNEs recognise a particular cultural environment in China and its distinct attributes. Even in the advanced Yangtze River Delta region, the executives spoke of a quasi-normal cultural milieu but also spoke of the need to develop strong relationships with relevant government officials. It was recognised that the level of relationship required in China extends beyond that normally encountered in the West. Executives spoke of the need to develop stronger guanxi links the further one goes from the eastern seaboard region, which represents a regional variation in the conduct of business affairs. Overall, the view presented was one where stronger relationships are required than Western business people are traditionally accustomed to. This research also corroborates the view of Macauley (1963) that relationships are central to business transactions. His views on the importance of honouring one’s commitments and the perceptions of the individuals within one’s industry are particularly relevant given the importance of not ‘losing face’ in Chinese culture.

An observation made by several interviewees was that one of the most important barriers to the development of guanxi by foreign businesspeople is the Chinese language. This view is supported by Bjorkman and Kock (1995), who point out that, while western businesspeople take part in discussions with their Chinese counterparts, it is impossible to develop a personal relationship as they do not speak the language. While some foreign business people speak Mandarin, they tend to be in the minority.

Guthrie (1998) argues that perspectives on guanxi vary directly with a firm’s position in the industrial hierarchy: the higher a firm is in the hierarchy, the less likely the firm is to view guanxi practice as important; the lower a firm’s hierarchical position, the more likely it is to view guanxi practice as important to its success. The reason for this is that firms in the higher levels of the industrial hierarchy already have privileged access to those with whom they have to deal, which they derive from their economic strength e.g. they have easier access to resources, and already have a strong relationship with the relevant government economic agency. Firms with a lower hierarchical position cannot enjoy similar privileges. This view is supported by this research. Those from particularly large MNEs did not place particular emphasis on guanxi or building strong relationships. This is to be expected as, given the economic importance of the MNEs concerned, they presumably enjoy easy access to senior officials. When the author asked further questions about this, one executive replied that ‘We have a very smooth relationship with the local government’. It can be deduced that executives associated with large-scale foreign investments are likely to enjoy high-level access to local authorities and are somehow granted guanxi by virtue of the scale of the investment.

Guanxi also poses certain risks to a firm. Employees’ personal networks may become liabilities when they return favours from guanxi contacts, whether within the firm or at competing firms. (Van Honacker, 2004) To obviate this threat, MNEs should seek to bring transparency to relationships and prevent conflicts of interest from developing. Guanxi can also be disrupted by staff mobility. When a staff member leaves an MNE the nature of relationships with third parties may change because the former employee had constructed relationships with customers and suppliers. Given the difficulty associated with the retention of staff, as identified by this research, this is a dimension which foreign investors should be aware of and see as a potential locational disadvantage. Van Honacker (2004) proposes a team-based selling approach to avoid customer contacts being concentrated on a single individual, but such an approach may not always be practical.

This research points to a strong cultural milieu in China, which a foreign investor must be cognisant of. The importance of building strong relationships was acknowledged by interviewees, in particular the need to build relationships with relevant officials. While this can also be of importance to business people in the West, it is probably fair to say that it is only of particular importance in regulated industries. The need to develop such relations in China is a cultural divergence from the business situation in the West and one which needs to be taken into consideration by investors. Those who have invested away from the developed eastern seaboard spoke of the need to develop traditional guanxi relationships. As argued above, China’s cultural environment can become a locational disadvantage within the context of Dunning’s model if due account is not taken of the cultural variations which exist. Accordingly, China’s cultural environment can be seen as presenting unique challenges which Irish investors would be unaccustomed to and which they should take into consideration.

Given the large-scale level of foreign investment and the introduction of Western business practices, the question has to be asked as to whether the unique Chinese culture and guanxi will persist. Arias (1998) argues that the economic and structural conditions that make guanxi relevant for conducting business in China are changing. While this research identified a regional variation in the intensity of guanxi, it was found that, executives continue to place an emphasis on the development of relationships even in economically developed regions. A study by McGrath et al (1992) found little breakdown of traditional Chinese cultural values in Taiwan, despite fifty years of exposure to western business practices. McGregor (2007) points to a resurgence in Confucianism, with the implicit approval of the Chinese authorities. He argues that this revival fits comfortably into the Communist party’s effort to reframe its single-party rule as part of a long-standing tradition of benevolent government. The influence of China’s culture is likely to remain an important component of doing business in China for the foreseeable future. Failure to take account of cultural norms is likely to lead to an increase in transaction costs in terms of the time spent in negotiating unnecessary obstacles.

Jones (1994) poses the question of whether or not the persistence of guanxi means that Chinese society is resistant to the globalisation of the Rule of Law. ‘This may indeed be the case, but we should also note that globalisation has singularly failed to eliminate cultural networks (such as “old boy” connections) from Western capitalism’ (Jones, 1994: 204). Accordingly, it is to the issue of the Rule of Law that we shall now turn our attention.

Contract Law

Macauley (1963) identifies the relative unimportance generally attached to contracts in the business world as emanating from an understanding on both sides of an agreement as to the nature and quality of a seller’s performance and the value of the relationship underlying the transaction. This research has identified an apparent paradox among Irish and non-Irish investors alike as to their views on the use of contracts in China. On the one hand they seek to negotiate contracts with a greater level of detail than they would do in the West, with provisions on obligations and penalties set out in a forthright manner, and on the other they recognize the general non-enforceability of contracts. One executive, though, spoke of his opposition to agreeing contracts with suppliers. His reluctance accords with the view of Graham and Lam (2003), who state that trust and harmony are more important to conducting business in China than having a legal contract.

Why is there an apparent paradox in the views of executives? Perhaps it emerges from the underdeveloped nature of law in China, as identified by one of the lawyers. He suggested that in developed economies the law can interpret intentions, whereas there is no developed body of case law in China. Therefore, foreign MNEs may be attempting to create comprehensive contracts so that, should a dispute emerge, they can point to the clear and unambiguous detail of the contract. However, there are two difficulties with this approach. Firstly, as identified by executives, the likelihood of obtaining a satisfactory outcome in the courts is not great. Secondly, as identified by one of the lawyers and several executives, contracts are ultimately linked to relationships. This research supports the view of Macauley (1963) that the ultimate non-legal tie is the maintenance of a successful relationship. However, this research is at odds with his assertion that business people are reluctant to engage in negotiating contracts. The research tends to support the view of Jones (1994) that a distinctive form of capitalism has developed in China, dominated by the Rule of Relationships rather than the Rule of Law.

This research provides evidence to support Jones’ (1994) view that China may be the ‘fifth little dragon’ in Asia, which demonstrates that the persistence of guanxi is not contradictory to the logic of capitalism. It also supports her observation that guanxi and relationships provide an alternative mechanism to the Rule of Law in China. This is not to state that China is a legal wasteland. Rather, this research shows that a ‘full legal order’ is absent and investors must place considerable emphasis on building strong relations with officials and business contacts.

This research also identifies the difficulty of enforcing contracts, which emanates from the lack of a tradition of resorting to court proceedings to oblige a party to fulfill contractual obligations. And it identifies the importance which executives place on approaching the executive branch of government in seeking to resolve disputes. One lawyer spoke on several occasions of using this route and expressed a preference for liaising with government at a provincial rather than at a local level. This approach flies in the face of the concept of the separation of powers, but Deng Xiaoping, the architect of the opening-up policy, never envisaged such a separation of powers. Perhaps, then, one should not be surprised that there is no strong tradition of the Rule of Law in China.

‘In the final analysis trust and harmony are more important to Chinese businesspeople than any piece of paper. Until recently, Chinese property rights and contract law were virtually non-existent – and are still inadequate by western standards. So it’s no wonder that Chinese businesspeople rely more on good faith than on tightly drafted deals’. (Graham and Lam, 2004:45) It is unlikely that the current legal framework will alter significantly in the short term, but that the situation will continue to improve incrementally.

Within the context of Dunning’s eclectic paradigm, the absence of the Rule of Law represents a locational disadvantage for Irish investors. Irish MNEs, in common with other firms in the West, do not place considerable emphasis on the negotiation of contracts when conducting business in the West. (Macauley, 1963) However, this research has identified that they do negotiate detailed contracts when conducting business in China. This represents a cost to the MNEs in terms of legal fees. A picture emerges of the need to build a strong network of relations and in the event of a legal dispute, adequate redress is more likely to be obtained in this manner than through legal channels.

Intellectual Property Rights

In 1979 virtually no legal protection was offered to intellectual property rights. Since then, legislation on trademarks was enacted in 1982, on patents in 1984, and on copyright in 1990. ‘China’s intellectual property rights protection, although strong in theory, are in fact almost impossible to enforce in much of the country’. (Lieberthal and Lieberthal, 2004:15) This research found that executives express concern at the lack of respect for IPR. These findings are supported by IBEC (2006: 3), which found that ‘the lack of intellectual property protection continues to be viewed as a significant barrier to trade in China and also, to a lesser extent, in some other Asian markets such as India and South Korea’.

Within the context of Dunning’s eclectic paradigm, the lack of respect for IPR raises issues in respect of all three advantages. The absence of legal protection is a locational disadvantage which China poses for investors. Peerenboom (2002) points to evidence that suggests that the lack of the Rule of Law and clear property rights have already taken a toll and will become an impediment to future investment and growth. ‘Anecdotal evidence confirms that some companies were scared away or chose to minimise their investment or to deliver second-grade technology rather than the most up-to-date technology’. (Peerenboom, 2002: 474) This view was evident in the case of the food sector MNEs. A chemical sector MNE executive was opposed to the introduction of the firm’s latest technology into China, given the previous experience which the MNE had suffered.

This IPR issue also creates a risk for the ownership advantages which MNEs possess. Intangible assets, including technology or patents, are of central importance for MNEs. (Markusen, 1985) Due to the lack of the strict enforcement of patent and trademark laws in China, the transfer of advanced technology is a concern for MNEs. Du Pont (2000) identifies reluctance on the part of MNEs to transfer technology due to the ‘copycat phenomenon’. Such a view is corroborated by the findings of this research.

Internalisation advantage refers to the manner in which the MNE organizes its activities in third-country markets. A legal system that protects intellectual property rights can create confidence in the use of independent subcontractors; while in the absence of protection, the MNE will tend to internalise production. Buckley and Casson’s (1976) internalisation theory contends that the protection of ownership advantage is a reason to retain production within the firm. Multinationality, therefore, can be a response to weaknesses in a legal system. This view is evident in the reluctance of executives to enter into joint venture arrangements because of the potential leakage of intellectual property to a competitor. While the use of a joint venture arrangement or M&A can hasten entry into a third country market, the findings of this research indicate that the use of either mechanism poses challenges in the case of China.

While executives from Irish MNEs which have invested in Eastern Europe have little direct experience of investing in China, the threat to the MNE’s intellectual property was cited as giving rise to a general reluctance to invest in China. One executive spoke of little hope of redress should such violation occur. He asserted that intellectual property is the core ownership advantage which the MNE possesses. Should this be compromised, it could have significant adverse implications for the MNE. The MNE was therefore unwilling to invest in China despite the market opportunity which China represents.

Another executive stated that the MNE would approach the executive arm of government should IPR violations occur. This reinforces the notion of the importance of guanxi and the under-developed nature of the legal system. In summary, it can be deduced from this research and the relevant literature that the lack of respect for intellectual property rights and the associated challenge of obtaining suitable redress through the legal system pose a potential locational disadvantage for investors.

In a professional capacity, the author has attended briefings in Shanghai’s High Court on the judicial efforts taken to protect the intellectual property rights of MNEs. Despite the efforts of the authorities, the evidence from senior executives is that counterfeiting continues. It is probably fair to say that it is becoming more controlled in the larger population centres, but such manufacturing would appear to continue, particularly in Guandong Province. It is in the long-term interest of the Chinese authorities to address this issue.

‘Addressing IPR issues more effectively will enable China to attract more long-term investment, especially in high-tech areas where technology transfer is more likely to occur in an environment in which IPRs are well protected. It will also encourage domestic creativity’. (OECD, 2003: 28)

Corruption and the Giving of Gifts

It is fair to say that corruption exists, to varying degrees, in all economies, both developed and developing. There is little information available on the level or scale of corruption in China. Had corruption been a major pre-occupation, it is fair to say that it would have been reflected in the interviews particularly with the non-Irish MNEs, because US companies (some of the non-Irish MNEs included in this research fall into this category) are subject to the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, 1977 (FCPA). The FCPA could be described as a reflection of the basic principles of Western business ethics, which seek to separate business dealings from the government officials with jurisdiction over those dealings. Breaches of the FCPA can have serious consequences for MNEs with American headquarters, even when the corruption takes place in a foreign subsidiary.

One should not confuse corruption with the necessity to offer a gift on meeting a new client for the first time. Gift giving is an important dimension of Chinese culture and it is expected that gifts will be offered. The etiquette of gift exchange distinguishes it from bribery and corruption. (Smart, 1993) ‘In bribery, the two parties enter into an impersonal relationship, linked by mutual materialistic utility. Such manipulative exchanges are geared up to shortterm immediate gain. Guanxi, on the other hand, is geared towards the cultivation of long-term mutual trust and the strengthening of relationships’. (Jones, 1994: 205) Jones (1994) points out that if foreign investors do not appreciate the role of guanxi, they will offer gifts as bribes. ‘On the other hand, long-term relationships of trust can help investors resolve problems faster, cutting through red tape and assisting with long and complicated negotiating procedures’. (Jones, 1994: 205)

Looking to future legal developments, Economy (2004: 98) argues that middle-class Chinese will want effective legal institutions to protect their newfound assets. She suggests that the new focus on home-ownership will assist in the development of the Rule of Law. Recognising the absence of a Weberian concept of law in China, Peerenboom (2002) develops a theoretical framework which argues that China is in transition from ‘Rule by Law’ to the ‘Rule of Law’. However, the version of the ‘Rule of Law’ which China will develop will most likely not be a liberal democratic version of the Rule of Law as it is found in Western economies. He proposes that one needs to bear in mind the differences in political and economic institutions and in cultural practices and values. He suggests that it is possible that China may develop an alternative to the Rule of Law concept as understood in the West and instead what may emerge is a form of the ‘Rule of Law with Chinese characteristics’.

However, even the creation of a culture of the ‘Rule of Law with Chinese characteristics’ cannot be achieved in a short period of time. The OECD (2003: 16) suggests that China ‘is striving to develop an impartial and effective court system, but, for institutional and manpower reasons, this work will take years, rather than months, to achieve’.

Regionalism – Advantages and Disadvantages for FDI

Even within China there are regional locational advantages and disadvantages to be considered within the context of Dunning’s eclectic paradigm. While an observer might consider China to be a homogenous unitary state, the de facto situation is that provincial governments have considerable devolved powers. Defence and foreign policy are the preserve of central government, but most other matters fall within the competence of local legislators. Mo (1997) contends that, in the area of FDI, local regulations often seek to fill the vacuum left by national legislation or supplement national laws in areas where they are silent. Eng (2005: 5) argues that ‘China’s rapidly changing environment makes it difficult for the central government to maintain regulatory uniformity across the land. Therefore, local rules could be at odds with those promulgated by the central government in, for instance, bank lending, consumer rights, factory operations and environmental protection’.

In transiting from a command economy to ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’, there was a decentralisation of decision-making power. This evolution not only increased enthusiasm for for eign investment at the local level, but also led to understandable competition between competing provinces and municipalities. ‘The fastest way for a leader at the local level to rise to a higher position is to oversee successful economic growth in the locality… this has produced a lot of de facto flexibility and initiatives at all levels, even in an authoritarian system with a socialist planning heritage’. (Lieberthal and Lieberthal, 2004: 15) It is important, therefore, to take cognisance of local regulations when considering the locational advantages which each province or municipality can offer. Indeed, incentives also vary at sub-municipal level. It is worth recalling a previously-used example on this point. One of the executives interviewed described his experience of negotiating with officials at district level in Shanghai when considering a location for a corporate headquarters. Given the prestigious nature of the MNE, local officials were keen to win agreement on locating the headquarters in their particular district (the local authority level). The result of these negotiations was that the firm effectively built their headquarters at little or no cost, when the additional fiscal incentives on offer were taken into consideration.

Investment has not been spread uniformly across China, with significant regional imbalances in FDI trends. Zhang (2002) points out that in the period 1983 to 2002 the eastern region of China received almost 88% of the overall FDI in China, the central region 9%, and the western region only 3%.[iv]In addition, the center of China’s FDI absorption has moved from the Pearl River Delta to the Yangtze River Delta. Du Pont (2000) identifies three distinct investment areas in the country: the four special economic zones favoured in the experimental period, the fourteen Open Coastal Cities, the three Open Economic Zones established in the Gradual Development Period, and the inland provinces, which he describes as requiring attention in terms of their economy and infrastructure. It is not surprising that investment is skewed in favour of the eastern seaboard. The reformers targeted China’s coastal areas in the early phases of the opening-up policy as the appropriate destination for inward FDI. Indeed, in the early phase FDI was permitted only in specially designated zones in this region. Regional variations are also evident in consumer purchasing power and income levels. ‘The average income in poorest Gansu or Guizhou is only less than 1/8 of that in the richest Shanghai or Guangzhou, and the gap is getting larger’. (Wang, 2006: 47) The east coast is where the highest income levels are to be found. Household size in the cities is 3.1, whereas it is 5.6 in rural areas, pointing to higher levels of disposable income in urban areas.

Investors from Ireland are more likely to select a location in the coastal region as this is where market opportunities are to be found. Another reason why Irish MNEs would be likely to focus on the eastern seaboard is the sectoral composition of the investment, with the emphasis likely to be on hi-tech, service or complex manufacturing sectors. These are predominately to be found in this region. In addition, if the investing firm is supplying another MNE which has invested in China, this MNE is also likely to be located in the coastal region. This view is supported by the National Council for US-China Trade (1990), which found that production bases for labour-intensive industries are shifting from coastal to inland regions.

This research found that the executives of Irish MNEs have identified regional locational disadvantages which one should be aware of. The executives spoke of the need to develop stronger guanxi links, the further one travels from the eastern seaboard region. Referring back to our earlier discussion on the legal system, Clarke (1995) points to considerable difficulties in having court judgments enforced in civil and economic cases. He points to the problem which ‘local protectionism’ poses, whereby local governments want to protect local enterprises. This problem was cited by one executive, who referred to particular problems when seeking to take legal action outside the province where its manufacturing facilities are located.

Although the Chinese Government has called for an increase of FDI in the central and western regions of the country, the flow of FDI to these areas still lags far behind that directed towards the coastal region. (Luo, 1998) While there have been high profile investments, Breslin (2005: 750) contends that the ‘much vaunted “look West” strategy aimed at encouraging more investment into non-coastal areas has largely failed to pull in significant new investors’.

Therefore, in considering an investment in China, Irish MNEs should take cognisance of the regional variations and seek to exploit regional locational advantages. If the object of the investment is to exploit market opportunity, then the eastern coastal region is where the highest disposable income is to be found. Also, when negotiating incentives, one should be aware of the differing levels of incentives available. This, of course, will be related to the nature of the investing MNE, with a premium placed on hi-tech MNEs.

Conclusion

It is generally agreed that increased knowledge of a foreign country reduces both the cost and the uncertainty of operating there. (Buckley and Casson, 1985) Irish investors need to be aware of potential challenges and include them in their business planning. Some are capable of rectification while others are more difficult to ameliorate. It is important that investors recognize that they are not conducting business in a developed economy and include contingencies to overcome obstacles.

This research has identified the principal locational advantage which China offers for Irish investors as being market opportunity. The overall experience of Irish MNEs could be described as very positive. While they recognise the existence of locational disadvantages they are keen to exploit the market opportunity which China offers.

Several locational disadvantages were identified, the most significant being the lack of protection for intellectual property rights. This is of importance for Irish MNEs given the general hi-tech nature of Irish industry. Failure to protect ownership advantages through the utilisation of appropriate internalisation advantages could place the ownership advantage of an Irish MNE at risk.

We can conclude that our sub-hypothesis holds and that the business environment in China is different from that experienced by Irish investors in traditional destinations for Irish outward FDI, particularly in the legal domain. Therefore, it can be argued that market imperfections exist, which distort the operation of the market, with a role existing for the state in removing such obstacles.

NOTES

[i] The firms surveyed were in four industries: agricultute, food-processing, car manufacture, and paper and cement.

[ii] Announcing a US2.5 billion investment in Dalian, north-east China, on 27 March 2007, Chief Executive Ortelli of Intel cited the increasing market opportunity which China represents as a key consideration underlying the multinational’s investment.

[iii] The teachings of Confucius (551-479 BC) have moulded Chinese civilisation. His teachings were the officially recognised imperial ideology for over 2,000 years, from 136 BC to 1905 AD.

[iv] The Eastern region of China includes Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and the provinces of Hebei, Liaoning, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guandong, Guangxi and Hainan. The Central region of China includes the provinces of Shanxi, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei and Hunan. The Western region of China includes Chongqing and the provinces of Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet Autonomous region, Shanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan are not included.

Previously published in: Nicholas O’Brien – Irish Investment in China – Setting New Patterns. Amsterdam, 2011