Budget Monitoring And Citizen Participation In The Netherlands

My name is Noureddine and I am a member of the training group that deals with budget monitoring. We have examined the prospects paper for 2013. On page 26 of the bill it is stated that in 2013 there will be 197 million euros in expenses. We’ve got an overview of the financial statements of 2011, which states that the district spent 243 million euros in 2011. Are we correct in understanding that over the next three years, spending will be cut by 46 million euro? In 2016, the expenditure is budgeted at 179 million. Meaning a 64 million difference. Was that the intention?

The expenditure in the social domain in 2011 was 68.7 million euros. If you look at the budget in the perspectives note, you end up with a total of 59 million for the social domain (counted are: work, income and economy, education and youth, welfare and care, sports and recreation, culture and monuments). This means that the social issues will receive almost 10 million euros less in the next 3 years.

Introduction

Thus spoke Noureddine Oulad el Hadj Sallam, one of the participants in the experiment Budget monitoring in the Indische Buurt (Indische Neighborhood) in Amsterdam during the meeting of the Council Committee Social of the municipality of Amsterdam (city district east) in June 2012. His speech addressed the content of the municipality’s perspective paper for 2013.

Noureddine’s speech signifies a unique moment in the Netherlands. Not only because a citizen without a financial educational background commented on the expenditure of the budget made by a governmental organization. But also because it led to a change in the way the local government determines the priorities of the prospective budget for 2014; namely, in co-creation with citizens. Co-creation entails collaborative decision-making concerning the allocation of the budget by citizens and civil servants. It is an important contribution to the enhancement of civil society within the Netherlands.

This paper describes the methodology of budgetmonitoring and its operationalization via the project in the Indische Neighborhood. The 12-month pilot project was realized by The Centre for Budget Monitoring and Citizen Participation, in collaboration with E-motive, University of Applied Science in Amsterdam (HvA), MOVISIE and members of local communities in the neighborhood.

Participants of the conference on budget monitoring in the Indische Neighborhood

Photo: Nills Delzenne

The launch of the Center for Budget Monitoring and Citizen Participation in the Netherlands

The idea to implement budget monitoring in the Netherlands was initiated by E-Motive of Oxfam-Novib. E-Motive connects knowledge and expertise from developing countries to Dutch professionals. In 2010, E-Motive introduced a group of social professionals in the Netherlands to INESC (Institute of Socioeconomic Studies), the expert on budget monitoring in Brazil. A year-long intense co-operation between active citizens and social workers from the Netherlands and INESC led to the launch of the Center for Budget Monitoring and Citizen Participation (Stichting Centrum voor Budgetmonitoring en Burgerparticipatie) in Amsterdam in December 2011.

The collaboration with INESC has played a significant role in developing the method of budget monitoring for the Netherlands. INESC has more than three decades of activism and research in Brazil and worldwide and believes that social participation is crucial in making governments accountable and promoting social justice. Since 1991, INESC has chosen public budget as a strategic tool to increase social participation in policy and in controlling the spending of budgets. INESC is specifically concerned with the allocation of public budget to promote social justice and human rights. They have developed their own methodology entitled Budget and Human Rights with the aim to verify the realization of human rights and their sustainability. Relying on education as a strategy, INESC targets schools located in poor urban neighborhoods (favelas) where they teach students the method of budget monitoring, the fundamental importance of active citizenship and influencing government policy.

INESC has achieved many positive results with this approach. One example is the ONDA project. Students participating in the project monitored the budget of their local government. They found out that two million reales was assigned for the renovation of their school. But the school never received the money. So the students attended a public hearing and managed to get an amendment for all public schools in the federal republic. Examples like this underline the strong impact that budget monitoring and civic participation can have on the allocation of public budgets.

INESC’s method was created for the context of Brazil and needed to be adjusted to the Dutch context. In comparison to INESC’s method, which focuses on human rights, our emphasis lies on social justice and civic participation. In addition, within the context of the Netherlands, the method of budget monitoring seems to fit active neighborhood organizations best as well as those communities that want to get a grip on the utilization of available resources in their neighborhoods.

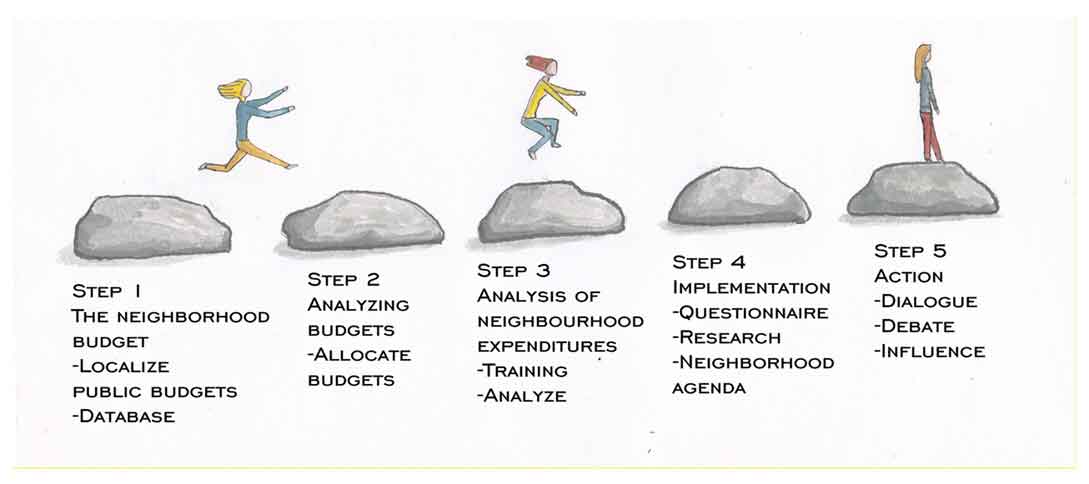

Roadmap of budget monitoring

The University of Applied Science in Amsterdam (HvA) collaborated with us in creating the roadmap of budget monitoring for the Dutch context. Below is the illustration of the roadmap and its five steps:

Graphic design: Merijn Bram Rutgers

Setting the ground for the pilot project

In 2011, we started to prepare the ground for the pilot project by choosing a specific neighborhood and collecting financial data of the local government.

The Indische Neighborhood

The context of the Indische Neighborhood in Amsterdam provided solid ground for the implementation of budget monitoring. Since 2008 many active citizen groups, called communities, have been working hard to improve the livability of this neighborhood and to develop instruments in order to improve social participation. In addition, these communities take on a very specific starting point in their work; namely, the citizen and his right to ambition. Budget monitoring contributes to civic participation because it facilitates citizens to screen, assess, and actively participate in decisions on public policy-making and government expenditure. Budget monitoring can act as a catalyst to start dialogues between citizens and (local) government about priorities, needs and tackling problems and therefore serves the right to ambition.

The struggle for transparency of financial data

Transparency of the financial data of local governments is required in order to implement budget monitoring. During the preparation phase in 2011, collaboration with the local government (Amsterdam, city district East) was difficult because civil servants and politicians did not share the same policy on budget monitoring. One of the major issues of co-operation, for example, was transparency in budgets. Specifically the information on the neighborhood budget was not present, so we had to find it ourselves. In 2012, the local district finally made the decision to publish financial data in a user-friendly way in the form of infographics. In October that same year, the government launched a website including the neighborhood budget. It is a pity that the local district decided to create this website without the co-operation with the communities. Co-creation would have made it possible for active citizens and civil servants to share information about the neighborhood. The system could also immediately have been tested on its user friendliness. Nevertheless, it is a start.

Putting the roadmap into practice the Indische Neighborhood

Step 1. The neighborhood budget

The first step in budget monitoring is to figure out the neighborhood budget. Different institutions invest in the neighborhood, but it is not always clear how much money is spent and on what. Examples of enterprises or institutions investing in the neighborhood are the local government and social housing corporations. Yet, access to the public budget is not always easy; therefore, it is important to come up with a strategy beforehand (in collaboration with the local government).

In this preparatory phase, we tried to localize public budgets. This was not easy because budgets and information about spending are not (yet) transparent in the Netherlands. So, we had to search for information in PDF-documents, found on the website of the local municipality. After a lot of research, we built a simple database.

Step 2. Analysis of budget allocations

Once the budget is public it is important to find out what the money is spent on. An example of the questions in this phase is: ‘How much of the budget is allocated to environmental issues, to social housing, or to youth issues?’

We analyzed the database to understand the budget for the Indische Neighborhood. We were unable to find all the budgets that were spent in the neighborhood. This turned out to be a common problem. As one civil servant told us: ‘We don’t know the budget for the Indische Neighborhood, every civil servant just knows their own budget’.

Step 3. Analysis of neighborhood expenditures

In this phase, the aim was to check if the public budget (not only governmental budgets, but also budgets from public housing corporations and other organizations with public money) is spent with reason. Is the money allocated to the correct funds? Some of the issues to be expected in this phase are:

– Funds are made available, but are not spend.

– Funds are spent on other things than spoken for.

– Funds are spent in areas and programs that do not prioritize social justice.

– Funds are spent in programs that do not correspond with the communities’ demands and needs.

Step 1 and 2 can be done without the communities. But budget monitoring is meant to be used by active citizens and communities in their participation process. This implied that people who never studied budgets before had to be trained to monitor budgets. In May 2012, we organized a series of trainings. The subject matters were: Budget cycle, annual report, and annual budget. Part of the training was the practice and theory of budget monitoring in Brazil, by trainers of INESC who made the group aware of the emphasis on advocacy and gaining political influence.

The participants of the training were spokespersons of communities as well as other community members. During the training we started analyzing the available public budget data. For example, we compared the 2011 budget to the 2013 budget. We also studied a list of subsidies for the Indische Neighborhood and we noticed that civil servants (and sometimes politicians) are the ones who decide which organizations received subsidies. We asked the local district to provide us with more financial data.

Step 4 Implementation

The fourth step is to weave budget monitoring into the participation process in the form of a neighborhood agenda (in cooperation with the communities). A neighborhood agenda is a social analysis of what is more or less important for the inhabitants. Questions to be asked are:

– What is important for the neighborhood, the communities and the inhabitants?

– What can we as inhabitants do ourselves?

– In what way we work together with institutions in order to influence policy?

– How are results to be communicated?

In this step all the necessary elements are collected and analyzed to prepare a dialogue with the local municipality.

To make a proper agenda the group decided they had to know the priorities of the citizens. What do citizens want for their neighborhood? A questionnaire was made based on the results of several participation events in the Indische Neighborhood. The participants went into the neighborhood to ask the opinion of 150 inhabitants, which were systematically archived and analyzed. The results: People gave a high ranking to projects for youngsters without school or work; projects and support for people in need, and the elderly.

One of the questions was: ‘Which budgets should be cut?’ and the most common aanswer was: The budget for civil servants.

After finding out the priorities of citizens, we re-monitored the budget of the local district and re-analyzed the annual report of 2011. We noticed that there was a big difference in 2011 between the budget and the spending of the budget on education, youth, and welfare. Altogether the difference was over 3,2 million euros.

Step 5. Action

Communities and experts on budget monitoring do a comparison of the neighborhoods wishes (neighborhood agenda) and the analysis of the spending. What is the budget? Has it been spent, and if not, why not. What is the discrepancy? This step creates a lot of opportunities that can be used by the communities:

– Using partnerships to reinforce the dialogue with the local government.

– Organizing meetings with the neighborhood stakeholders.

– Advocacy (participation in public hearings, talking to civil servants, public campaigning, media strategy etc.)

– Co-creation – draw up the budget together with local government

– The power of communication and publishing data visualization (using digital media).

The training group used the financial data that was gathered and went to the political board of the local district to ask questions about budgeting and spending. (The answers were given 3 months later.) In addition, on the basis of the findings from the training and questionnaire, the community members decided to write their own perspective paper, with a long-term policy, instead of an agenda for the neighborhood.

Conclusion

The project held in the Indische Neighborhood in Amsterdam shows how budget monitoring can act as a catalyst to start dialogues between communities and government on priorities and where public money comes from and how it is spent. It is an important initiative towards a more democratic society: Major decisions on public budget are made in collaboration with civil society organizations, governments are held accountable, and the budget as well as its allocation becomes transparent.

Moreover, the outcomes of the project on budget monitoring are not interesting for just the Netherlands; they correspond with important shifts that are taking place on an international scale. Citizen participation and transparency are two issues that rank high on the agenda of many civil society organizations, governments and governmental institutions worldwide. Numerous initiatives try to facilitate a dialogue between citizens and governmental institutions, such as the Open Government Partnership established in 2011. In the light of these social and political trends, budget monitoring is an efficient tool that can be implemented to achieve such aims in the Netherlands and abroad.

For more information: http://www.budgetmonitoring.nl/english

and: http://www.inesc.org.br

About the authors:

Zeynep Gündüz is project coordinator at the Centrum for Budget Monitoring and Citizen Participation. She gives workshops and training on budget monitoring in the Netherlands and abroad. She has currently completed her Ph.D on the impact of technology in arts and society.

Marjan Delzenne is founder of the Centrum for Budget Monitoring and Citizen Participation. She gives lectures and trainings on budget monitoring in the Netherlands and abroad.

She also works at the family-business Delzenne as consultant or interim manager for governmental and civil society organizations.