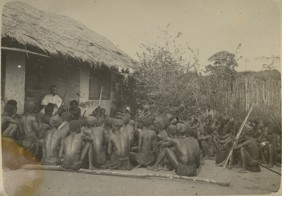

Primitive School, Mission area MSC, location and date unknown

“I have been interested in the Congo all my life, because I always wanted to be a missionary in the Congo, even as a little child. And so in a way I paid some attention to it, but only the achievements of my heroes at the time – a number of family members were missionaries and the mission exhibitions, the missionary action. The Congo came to us through missionary work and it was very heroic. …I remember the moment to the minute when I discovered the background or the ‘depths’ of the colonisation of the Belgian Congo. And then I got the feeling, which I still have today, that during my training, my education, I had been deceived about the Congo.“[1]

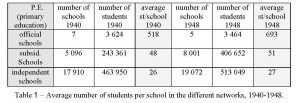

Flemish and, by extension, Belgian missionaries left for the Belgian Congo in droves. The Statistical Yearbook of the N.I.S., which had a separate section for the colony, recorded a few tables with data about the ‘white’ population. As well as divisions on the basis of nationality, gender and place of residence, for a number of years it also included a “class division“. In this table, the population was divided into three categories: ‘civil servant’, ‘missionaries’ and ‘general public’. The presence of a separate category for missionaries points to the fact that they were very important in colonial society. On the basis of the available figures it can be posited that during the interbellum period, religious workers comprised 10 to 15% of the white population. This percentage was certainly not only men, the proportion of female religious workers was fairly stable throughout the colonial period and amounted to over 40%.[2]

The above quote, from an ‘experienced expert’, indicates that the conceptual world of the missionaries was not an empty page, that they did not leave without expectations and that they did not work in a vacuum. The colonial attitude in general has frequently been the subject of analysis. The question raised in this chapter is more specific: what can be said about the conceptions and attitudes with which the missionaries left for the colonies? A number of aspects of missionary life have been the subject of research in recent years. Jean Pirotte, who wrote an important work on the mission periodicals in Belgium, gives a good overview of relevant research questions about the missionaries during the colonial period.[3] He divides these questions into a number of categories, more specifically: the interest in the missions, the ‘agents’ of missionary work, the support on the home front, the use of time and space, the missionary ‘conscience’ and the dialogue between societies. Further, a number of works have recently appeared which try to capture the missionary spirit, at least partially. It is certainly not the intention to deal with all these questions systematically in the framework of this thesis, let alone to answer all of them.

In any case, it is with the necessary reservation and some caution that we attempt the assessment of the ‘intellectual baggage’ of the missionaries who left for the colonies. Indeed, the difficulty with which this specific theme is dealt in the existing scientific literature is striking. When Depaepe and Van Rompaey discussed the ideas of the missionaries they talked predominantly about the appreciation of the black intellect and character and they supported themselves, necessarily, with the views of a pair of figures considered influential, namely Pierre Charles and Gustaaf Hulstaert.[4] Thus when, by way of conclusion concerning the missionary attitude after the Second World War, they make a pronouncement like “Even so, most missionaries could still only muster very little appreciation for the traditional milieu“,[5] this can serve as the necessary correction to the still dominant view of the missionary as the ‘friend of the Congolese’. Even so, the statement must at the same time be interpreted itself. The reality was, after all, more complex than that. It is not appropriate to paint all missionaries as uncompromising, dogmatic people, who did not want to learn about their surroundings, or at least did not try to understand them.

Moreover, it appears from the available literature that it is very difficult to pursue certain conclusions or hypotheses to the level of daily practice. Concretely, scientific literature about missionary work and mission history speaks a lot about ‘missiology’ itself. Missiology counts as the scientific approach to missionary work, which itself developed during the colonisation of Belgian Congo. This scientific transformation occurred at the University in Leuven as a result of the Jesuit Pierre Charles’ initiative and the Semaines missiologiques de Louvain, which he organised. The question of whether these theories and ideas actually found their way into the field is far harder to answer.

As an example: the CREDIC (Centre de Recherches et d’Echanges sur la Diffusion et l’Inculturation du Christianisme), connected to the University of Lyon, organised a colloquium in the early nineties of the twentieth century on the subject of the training of missionaries.[6] In the different contributions offered in the presentations of the colloquium, however, no clear link was established between the missiological science and work in the field. The question of whether there was an influence from the Missiological Weeks on the formation of missionaries is only formulated explicitly by one participant: “Ultimately, what influence could the Missiological Weeks in Leuven have had on the preparation for missionary work given to the Misionary Sisters of Our Lady of Africa? It is truly very difficult to establish this. Perhaps it may be labelled ‘vital interaction’.” The mission sister in question subsequently posited that the possible influences that came from missiology or from the themes discussed during the Missiological Weeks were, in any event, very indirect. In any case, they are not to be found explicitly in the archives.[7] There were various training initiatives covering the needs in the field but the same author mentioned that even after the Second World War “the people responsible for training realised that all the Sisters had little culture: years of study were required before they could carry out the profession: nursing diplomas, primary school teachers, domestic education, English (necessary in Anglophone Africa). There was a sense of an immense need for training.” Taking into account that these assertions were made in the framework of a French congregation of sisters, which was active in other parts of Africa, we must ask ourselves if this tendency also recurs in the information and documentation about the formation of (primarily) Belgian missionaries in congregations which were active in the missionary region of Coquilhatville.

Lesson by a Father in the Equator area

Closer to home, it also appears from recent research that the truth is certainly not to be found in the missiological discourse. Carine Dujardin, who did extensive research into the missionary work of Scheut in China, asked a number of former missionaries about the influence of the Semaines Missiologiques, which seemed to have been of national and even international renown at the time.[8] The answers she received confirm that this influence was almost non-existent. Dujardin cites a number of reasons for this: the rather more elitist character of the missiological movement, the isolation of most active missionaries, the seniority principle which obliged new missionaries to adhere to certain rules of obedience and the practically focused and even anti-intellectualist profile of most missionaries. She also gives a fifth reason: the education of the missionaries themselves, which was usually very elementary.[9]

If it is thus already clear that there is no necessary connection between the scientific mission discourse and that of the people in the field, how is a researcher to try and deal with this problem concretely? He or she can try to observe these people themselves and to look at their ideas in detail. I have in this case chosen to work in two phases. In the first phase, the situation with which the missionaries were confronted in the period preceding their ‘career choice’ was analysed. Firstly, as an introduction, I will give a short general sketch of colonial conceptualisation in the mother country. The image formed by a person about an in se unknown, distant and removed phenomenon will after all be greatly influenced by the ideas about it circulating in the society in which he or she lives. Secondly, a more specific examination will be made of the image that was entwined with that situation: the image of the missionaries themselves and of their activity. From this, presumably, it will be possible to deduct in a general way which considerations formed the basis for a person to leave for the Congo as a missionary. Logically, the question of where these images and ideas come from must also be asked. The answer to this question leads to the second phase: considering that conceptualisation is fundamentally influenced by education and training, the analysis of the general situation is followed by the analysis of the specific context in which the aspiring missionary was educated and trained. As part of this subject, a more specific examination will be made of the education of the people working in the vicariate of Coquilhatville. Furthermore, an attempt has been made to complement and complete the written documentation as much as possible by means of personal testimonies.

1. The broader societal context as an influential factor

1.1. Promotion of the colony and missionary activity in Belgian education[10]

In any case, conceptualisation about the colony and missionary activity was clearly related to training at school and in particular with the intellectual framework given with this training. In his research into the origin of the vocation of missionaries, Claude Soetens posits that it was not the school as such that created missionary interest for the majority. According to him, school was an environment dominated by the religious workers. He posits that primarily through this, feelings of responsibility, service and selflessness could be developed in the young. That these values played a big role in choosing a missionary vocation can hardly be denied, although this statement, in our opinion, does not put enough emphasis on the power of societal pressure. The connection between the two is therefore not an automatism. As the Jesuit Joseph Masson said when asked in an interview about his memories of the beginning of the Missiological Weeks: “In 1923, I was a pupil in third year Latin at the St-Servais College in Liège. I was undoubtedly already enrolled for the missions: sorting out stamps, collecting and dragging away old paper to help them.“[11] This statement suggests that the environment in which people lived influenced the children to develop in a certain way, without this having to be decisive as such.

1.1.1. The government and the promotion of the colony at school

We can assume that the missionaries received the same schooling as the majority of other children and consequently also concerning their vision of Africa, the colonies and the Africans. There are clear indications that conscious effort was made early on to ‘steer’ the Belgian population in its view of Belgium’s presence in the Congo. One of the themes discussed at the Congrès colonial national, organised in 1920, was how to imprint the population with a favourable stance towards the colony. It was posited: “In order to educate the nation, encourage vocations, in short to form public opinion in a colonial regard, it is of primary importance to organise colonial education in the schools of all levels in an interesting and intuitive way.”[12] Much earlier, in 1905, Leopold II had made his own attempt to impart more international sensitivity to his subjects via education. In that year, the Belgian government organised an international scientific conference in Mons on L’expansion économique mondiale (so-called ‘world expansion’) and this at the instigation of the King.

Colonial politics as part of a broader expansionist idea was one of the central themes of the world expansion conference. One of the sub-commissions at the conference was, in fact, devoted to education. The central idea put forward there was to adapt the school curriculum in such a way as to make people more amenable to everything taking place outside their own direct and limited social environment. The possibility of emigrating abroad was then also included (for example to the colony). That this was not merely a gratuitous remark made at a conference can be seen from the fact that a brochure about the proposed reforms to the education system was published after the conference.[13] The option to make world expansion a permanent focus point in schools fitted a certain tradition.[14] For the time being it remains difficult to ascertain how far the proposed reforms were actually introduced. From the studies available on the subject it can be concluded that this certainly did not happen as planned by the government. However, it does appear that the colony was placed on the school curriculum. This can be deduced, for example, from the fact that at that time song lyrics about the Congo circulated in pedagogical periodicals on the home front.[15]

1.1.2. The Catholic Church and the promotion of the mission at school

The colony was also present in education via another route. The official mission propaganda was strongly connected to and interested in education. The ‘Heilige Kindsheid’ or ‘Holy Childhood’, founded in 1843, was an official organ of the Catholic Church[16] aimed at the education of children to the missionary spirit and cooperation, through prayer and material aid, to relieve the suffering of less fortunate children in mission countries. I refer to it because for years this organisation was responsible for the missionary idea being present very strongly in Belgian society and especially in education. In Flanders, it developed particularly quickly and was present in every Catholic primary school. By means of specific periodicals and pedagogical instructions it certainly had an influence in the classroom: The Priests’ mission union, periodicals such as ‘Annaaltjes van de Heilige Kindsheid’, ‘Tam-Tam’, mission poems, mission songs, the ‘Romereis’ (trip to Rome), the ‘Hemeltrap’ (stairway to heaven), etc. The arsenal of pedagogical aids intended to produce support, respect and money for the missions was impressive. Apart from this, the mission idea was promoted on a large scale.

In a very extensive article in De Vloed, a periodical for missionaries in training, the MSC Joris Vlamynck sketched an image of what was happening in Flanders in the field of missionary action in the second half of the 1930’s. Vlamynck described both in-school and extra-curricular activities which were organised for the benefit of the missions or the theme of which was at least missionary. In the first part, about the Holy Childhood, it was stated that their proceeds for the Diocese of Mechelen were nearly one million Belgian francs in 1931, an enormous amount for that time. The article refers to the annual membership contribution of the Holy Childhood, to contribution cards, to offertory boxes. Furthermore, aside from the financial information in the article it is apparent that a lot of attention was paid to the missions. Missionary duty was, according to Vlamynck, forced upon educational personnel in pedagogical periodicals and at annual educational conferences.

Situated further outside the school environment were the ‘Eucharistische Kruistochten’ or ‘Eucharistic Crusades’, established by the Norbertines of Averbode in 1920.[17] The aim was, at first glance, primarily to keep the fire and enthusiasm for the missions burning through frequent prayer. However, Vlamynck posits that means other than prayer could be employed: “Even the material mission action is included in the E.K. (Eucharistic Crusades) life: in the mission sewing circles the crusaders find a way to turn their apostles’ spirits into deeds.” The financial aspect was not forgotten either: “Through the E.K. management collecting boxes were made available from the E.K. departments; the profits, which were deposited by the members, went to the S.P.L. for training native priests in the mission.” The Eucharistic Crusades were apparently a well-structured organisation with 200 000 members at the time of Vlamynck’s article. The movement must of course be situated in the broader societal context as part of the Catholic reaction to the progression of moral corruption. The Crusades were aimed at the whole population and had youth divisions and adult divisions, both supported by a solid press infrastructure. Among others, Zonneland and other publications from the Goede Pers (the editing house of the Norbertines in Averbode) were aimed at children. For the other groups there were also specific publications. Vlamynck furthermore mentions the organisation of divisions in the Congo, for which the Crusades on the home front supplied the necessary materials: “To ease the task of the missionaries in establishing and leading the movement, the E.C. centrel of Averbode will provide all the necessary information about spirit and method and provides them with rich E.C. documentation and literature: books, brochures, papers, etc.”

1.2. The Belgian Congo in schoolbooks

In the framework of this research the schoolbook can be considered the supplier of relevant information in two different ways. On the one hand, it was a tool used by the ‘coloniser’ to bring ideas, concepts and values across to the ‘colonised’. We will come back to this concept later. On the other hand, of course, the schoolbook was at the same time used in the western education system, also to communicate ideas, concepts and values. Both these cases raise the following question: How much relevant information can we obtain concerning the formation of ideas as a result of the content of these schoolbooks? We will start here with the discussion of the schoolbook in Belgian education as a tool for the formation of ideas about an unknown culture, in this case, the Congolese.

1.2.1. Conceptualisation in schoolbooks

Scientific research concerning the formation of ideas about other cultures using the medium of Belgian schoolbooks is rather limited to date. The most extensive study available is the doctoral dissertation of Antoon De Baets, from 1988, about the influence of history textbooks on Flemish public opinion concerning non-Western cultures, using a study of the content of history textbooks from secondary education in the period 1945-1984. This study is interesting in this context for at least two reasons: Firstly, because it contains an overview of previous research on conceptualisation in history books in Flanders. Information on this subject gathered by the author confirms and strengthens for Belgian Congo what is generally applicable for other regions: very little scientific research has been carried out into conceptualisation in schoolbooks.[18] Secondly, the study is important because the author questions how what is learned at school influences the way people think about other cultures. Here he convincingly shows that research into the influence of a schoolbook on the formation of ideas puts this influence into perspective. On the one hand, it is clear that it is difficult to ascertain how certain ideas are retained from the texts of schoolbooks and the extent to which they are representative for more broadly applicable values and thoughts within a society. On the other hand, the medium of schoolbooks almost vanishes completely when the multitude of other media and influences affecting the children during and after their time at school are also taken into account.[19]

Schoolbooks can only provide information about the transference of values on a general level. The conclusions that can be drawn from the research into schoolbooks are never final, they are only indicative. The manner in which schoolbooks deal with particular themes therefore only reveals something about what the makers of the book think. It does not necessarily tell us what the pupils who used the book did think. It can be assumed, however, that the information given in schoolbooks did, in general, fit with what was thought about those things in a broader social context. The producers of the schoolbook thereby functioned as a kind of mirror, reflecting current ideas via the book. The conclusion may be drawn that the same types of information or the same kinds of messages circulated via other media and other means and thus also reached the pupils.

1.2.2. The image of the Belgian Congo

As far as the Belgian Congo is concerned, there are strong indications that the same types of information circulated in various ways and that particular images and ideas were part of a whole concept that was fairly generally present in Belgian and Flemish society. This statement can be reinforced, for example, by investigating the ideas and concepts about the same themes in different milieus. For the missionaries, the strong interrelationship of education and church must have unmistakeably contributed to the unity of conceptualisation within certain social groups from which the missionaries were recruited. We have already pointed out that the image given of missionaries at school could largely have been created (and maintained) by the missionaries themselves. It suffices to point out parallels between the image given in mission periodicals and that shown in schoolbooks.

There is very little material available on the way in which the colony was presented in Belgian schools. One study was devoted to the aforementioned ‘world expansion conference’ (a very inadequate translation of congrès d’expansion économique mondiale). It is a master’s thesis which examines the impact the plans, made in preparation for the conference on world expansion, had on the primary school curriculum. This research was done on the basis of reports from conferences on education and periodicals on education. In another master’s thesis the phenomenon was approached on the basis of schoolbooks.[20] This research concerned the manner in which the colonial period was written about in a number of history books used in secondary education in the period between 1900 and 1980. The conclusions of this study, based on the contents of about sixty different textbooks, can be summarised as follows:

In the first period, from the beginning of colonisation until the First World War, hardly any attention was paid to the colony in the fatherland’s history books. Some events concerning the King were mentioned, of which the most prominent was about the protection and civilisation of the Congolese, the war against Arabian slave traders, evangelisation and the tapping of new markets. In the interbellum period, the approach changed to a more contextual one, in the sense of heightened interest, and the results of colonial action were further discussed. Devoting entire lessons to the colony only became the norm after the Second World War. A more detached approach to the first years of colonisation was introduced, especially compared to the heroic proportions the deeds of King Leopold II had taken on in earlier periods.[21]

In addition, there is also a study by Edouard Vincke from 1985 on the image of foreign cultures. This concentrated on Belgian French language geography textbooks, published in the period 1880-1980. His research, based on a representative sample of schoolbooks, also provides information on the image that Belgian pupils received about foreign peoples in distant lands. It is primarily a study about ethnocentrism, tracing the evolution of the concepts of ‘race’ and ‘primitivism’ over a period of 100 years. Vincke also researched a number of concepts that concerned the image of the Congolese. Regarding the assessment of the phenomenon of colonisation by the authors studied he states: “It is possible to follow the changes of position regarding colonisation. During the first period, there is a direct panegyric for the possession and exploitation of riches. Then there is a panegyric for the humanitarian and economic work, the valuation of the spiritual and material welfare. Finally there is a panegyric for development in the modern sense. A fashionable polemicist (P. Bruckner) vehemently criticises Western culpability in relation to its old colonies and the Third World. This is a criticism from which the analysed authors escaped.” [22]

Marc Depaepe also paid attention to data about ‘the colony at school’ in the study and exhibition ‘Congo, a second fatherland’. Based on his assertions, I can only draw the following conclusions from the above studies, which correspond strongly in a global sense. Though the emphasis was on progress and the results achieved through the civilising action, the basic position towards the Congolese remained fundamentally racist, even though this position was based on so-called scientific premises. The Congolese were stuck, according to this conceptualisation, between actual progress and inherent inferiority. This justified the continued presence of the colonisers, whose bravery and achievements, of course, were also endlessly praised. The Congolese were also praised insofar as they achieved the image that the colonisers themselves wanted of them.[23]

The Groupe Scolaire Building in Coquilhatville

A striking example of this very ambiguous position is to be found in ‘Taalwerkboek 5‘, a textbook in Dutch for the sixth year of primary school, published in 1960. In this textbook, over a total of thirty reading lessons, three texts are devoted to the Congo. The first of the three is entitled “Pioneering work in the Belgian Congo” and deals with the creation of the colony, the role played by King Leopold II and the memory of a number of colonial heroes (De Bruyne and Lippens, Dhanis and Jacques). The heroic sacrifice of the missionaries is also discussed. Furthermore, it is posited that Leopold gifted the Congo to Belgium, to fulfil his initial purpose. The second lesson has the title “A metropolis grows” and considers the growth and prospects of Leopoldville. Finally, the third text describes a remote mission post. It is entitled “Where the tam-tams drum“. Through their choice of vocabulary, these last two texts clearly illustrate the contrast created in the depiction of the colonial undertaking. Numerous strengthening adjectives were used in these texts to show this image as sharply as possible. In Leopoldville, at the ‘wide’ Congo River, ‘spacious, beautiful’ avenues formed a ‘modern’ city, with ‘tasteful’ buildings, ‘luxurious’ hotels, ‘magnificent’ bank buildings and ‘well-kept’ gardens, ‘sober’ school complexes and ‘proper’ hospitals. By contrast, many dangers had to be risked to get to the mission post in the bush, over ‘winding, narrow’ roads. However, the mission post itself was an oasis of civilisation, as literally stated, because “the remaining, extensive mission territory is located even further away: thick woods along the hills and swamps in the valley. (…) Far away the dull, heavy beat of the tam-tams is heard. Over there, in that mysterious distance it is hard work; the fetish servants and the sorcerers still have great, ill-fated influence over the population. They are the worst enemies of the civilisation of Congo. Slowly we come to understand what mission work means.”[24] Naturally, this kind of description shows how the authors, consciously or unconsciously, represented Congo as a distant exotic place. It was described as a place where only hardworking, motivated people could go to take part in a heroic but far from completed mission to alleviate the misery of the totally different people who lived there.

An important marginal note here: Congo and everything that had to do with the colony was, of course, only one of the topics considered in these books. Relatively speaking, the attention devoted to this topic was not so large.[25] This realisation also applies to the political interest in the Congo and perhaps to society in general. The colonial idea must have remained strange and mysterious in public opinion, far from the daily reality. Although the colonial propaganda reached even the smallest villages through education and missionary action, there is no doubt whatsoever that the image of the colony, as it came about through missionary and state propaganda, was essentially ethnocentric and certainly persisted until after independence. This image perfectly corresponds to the descriptions generally spread by the colonial propaganda services.[26]

1.3. Where did the missionary vocation come from?

The concrete situation that brought young people to the point of becoming missionaries can partially explain their intellectual frame of mind and the worldview from which they approached their job as missionaries. Since the beginning of the 1980s scientific investigation in this area has made clear progress in collecting and analysing the testimonies of those involved. However, there are as yet no coordinated studies published.[27] For the period preceding missionary life, including the motivational factors and the surroundings in which those involved grew up, two research projects can be cited in the Belgian context. In the first case there are a hundred testimonies from missionaries that were collected by the Centre Vincent Lebbe in French-speaking Belgium during the mid-eighties. This project had a historical nature; the intention was to determine what memories those involved still had of their lives as missionaries. The results of this research were seen as an initiative towards the creation of a ‘database’ of missionary testimonies. The second case concerns a survey of one hundred missionaries throughout Belgium at the end of the 1980s by Carine Dujardin. She was aiming specifically at the value pattern of the missionary population in the year 1989 and their position in the context of changes made after Vatican II.

In both cases those interviewed were mainly African missionaries. Each time a number of general questions were asked concerning motivation, attitude, descent and such, that can offer us useful information in the context of our investigation. In both cases the researchers reached the conclusion that there are no general lines to be drawn concerning the descent or motivations of missionaries, although there are a few trends. For instance, it was found that the great majority of missionaries came from what was described as ‘the higher middle class’. In the second investigation, which was geographically conducted over the whole country, there was also an overwhelming representation of people from the countryside.

The class-bound division of the missionaries may not seem significant but from the results of the two investigations it is apparent that the ideological base was clearly present in many cases, and this in a variety of ways. The Catholic action, which was fully developed during the interbellum period, was a meaningful framework of reference for very many missionaries during their youth. Catholic action and missionary action overlapped through this. School was also, in a great majority of the cases, taken into account as a stimulating factor when deciding to become a missionary. The Catholicism of the private life seems to connect to this easily in most cases.[28] From Soetens’ research it is further apparent that there were many practical reasons to start work as a missionary. In this way the author emphasizes that school is often named as a stimulus in general but that there were mostly other, more exact factors that were mentioned: a particular religious person who exercised a decisive influence; older friends who took the same road; missionaries who came to give talks at school.

For Soetens, one of the most important conclusions is that among the reasons given there was almost nothing said about a broader church project. As a possible explanation he puts forward that the specific missionary training before departure was very brief or lacking entirely. Of course it is also possible that the nature of the research method used could have something to do with this: no doubt interviewees will sooner answer with facts to specific questions. When they are questioned about their motivation they might not spontaneously talk about a system or broader phenomenon but call on an individual person or concrete occurrences. Finally, it is a noteworthy conclusion that school had as good as no influence on religious women. The shorter school career and the fact that most orders of teaching sisters had their own recruiting system and only had missions quite late (or not at all) would have been the cause.[29]

What was the image of the missionaries themselves in society? This too is a complex question. Keeping in mind the influence of the church structures on people’s everyday lives, and considering the decisive influence of other missionaries at the origin of new vocations, it is likely that the image of the missionaries was shaped by the actions of missionaries. Also, this kind of literature, including the mission periodicals (and therefore the Catholic propaganda in the strict sense), was itself a part of the influence on the creation of vocations in the younger generations of priests. In his study on the shifting mentality of Belgian mission periodicals during the first half of the twentieth century, Pirotte suggests that few countries had more different mission periodicals than Belgium.

According to Pirotte, the main aims of missionary action that were emphasised in the mission periodicals were proclaiming the message of salvation and establishing the church community in a strange territory. On the subject of the missionaries, Pirotte concluded: “Firstly, there is an excessive simplification in the presentation of the missionary. This simplification is not only manifested in the absence of profound reflection but also in the dichotomy used between the good and the bad; the missionary, shown as the hero of good, facing the forces of evil represented by the enemies of God’s work. A second conclusion is of diffuse romanticism which may be seen in the periodicals throughout the period studied.” From there, he appropriately concluded: “Undoubtedly, a large number of missionary qualities may be exact and we certainly may not ignore their generosity and endurance; but, in part, this image appears tailored with a view to being shown as attractive to young people avid in their devotion and self-sacrifice” Nevertheless, at the end of the interbellum period a critical tendency came about in the periodicals that opened themselves to deeper reflection (these were a minority) and turned against the overly sentimental, romantic and heroic image of the missionary and his task in a strange land. These kinds of periodicals are situated on the side of missiological science. After a global quantitative investigation Pirotte decided that in the mission periodicals, in general, the emphasis was sooner placed upon proselytism, the gospel and spiritual welfare rather than moral and humanitarian objectives. This conclusion was even more true of the Catholic than the Protestant periodicals.

2. Specific training for missionaries

2.1. General

Dujardin states that specific training for missionaries in the nineteenth century was very limited and was practically nonexistent. Most congregations only provided the normal priest training consisting of the noviciate, a number of years of philosophy and a theological education. Apart from this a distinction had to be made between the specific mission congregations and other religious congregations. For specific mission congregations, attention was only given to the place and circumstances in which the missionaries would find themselves in the future but this attention was very fragmented and certainly not scientific in nature. In the other congregations, particularly the women’s congregations, the level was even lower. The ideas of missionary work and education did evolve over the course of the twentieth century, also influenced by a number of papal encyclicals (namely Rerum ecclesiae from 1926, Saeculo exeunte from 1940, Evangelii praecones from 1951 and Princeps pastorum from 1959). Apart from the fact that three of these four encyclicals could only have had an influence after the Second World War, it must be stated that Dujardin did not announce any changes in the condition of the missionary training and thus it seems that the nineteenth century situation endured in the twentieth. The development at or around Leuven University in terms of missionary training shall be considered in what follows. There are two reasons for this: firstly, MSC will be considered in particular with regard to the treatment of the concrete training initiatives in congregations. They undertook a great deal of their training in Heverlee, close to Leuven. Secondly, as a Catholic university, the University of Leuven was noticeably at the forefront in this regard. Pierre Charles has already been referred to, but to what extent his ideas and the activities he organised were applied in ‘the field’ will have to be investigated in more detail.

2.1.1. Towards a central missionary training?

Playground Girls School Sainte Thérèse in Coquilhatville, 1950s.

There were several attempts to create a general training institute for missionaries in Belgium. At the start of the colonisation of the Congo by Leopold II an African seminary was founded in Leuven at the request of the King himself as part of the negotiations with and the search for Belgian missionaries. The seminary received the task, analogous to that of the American seminary, to train future missionaries for Africa. It functioned as a general training establishment for missionaries from December 1886 onwards but always suffered from a lack of resources and, particularly, a lack of students. In May 1888 it was taken over by the congregation of Scheut. According to Marcel Storme, courses in theology and the basics of African and Arabic languages were taught.[30] It may be assumed that, considering the early stage of the colonisation and the missionary work in the free state of Congo, there was no place for other subjects. The curriculum also included “The concepts of hygiene and essential medicine in an equatorial climate.”[31]

A second attempt to set up a general training for missionaries took place in the 1920s. In March 1923 the so-called ‘militia law’ was passed in the parliament. This allowed missionaries to be released in part from military service, on the condition that they “(…) spent one school year in higher education in a nurse-missionary training programme that is accepted by the Minister of Colonies and whose curriculum has received his approval“.[32] This centre for higher education was situated in Leuven and opened in November 1923. Strictly speaking the training was not a part of the university curriculum since it was very practical. The principle behind it can be seen from the words of Rector Ladeuze, who noted in early March 1923: “The house has just voted that missionaries shall be relieved from military service on the condition of doing a year of colonial studies (in addition to a few months in the field). Reason: services that they may provide in the colony during wartime, or in the absence of doctors“.

It is clear from the existence of a complete curriculum that there were plans for a specific missionary training at Leuven University. This curriculum made a fairly global and wide impression and paid attention to history and languages, ethnology and teaching, agriculture, transport and engineering, besides a more traditional focus on the elements of medicine and hygiene. It was actually a slight extension of an already existing curriculum. Like other universities, the Catholic University played to the demand for staff with higher education when the Congo went over to the Belgian state in 1908. Training in colonial sciences was introduced, as in Brussels and Liege, in the framework of the Ecole supérieure de sciences commerciales et consulaires, where a degree in the Sciences coloniales could be attained in one or two years. Considering its place in the organisation chart the training was more situated in the ‘economic’ or ‘commercial’ area.

One of the professors in this training course was Edouard De Jonghe. It has already become clear that he played an important role in shaping the colonial education system. However, De Jonghe was also very taken with colonial education at home in “the metropolis” and undoubtedly played an active role in the decision-making on this subject. At the same time it can be seen from his correspondence with Ladeuze that these two maintained very good relations. The question also arises as to whether the nurse-missionary training was set up following demands from Leuven University. This cannot yet be answered definitively on the basis of the available information.

The education in the colonial sciences mentioned here should also have formed the basis for the new ‘missionary’ study option, which Ladeuze and De Jonghe were aiming for. It appears from the correspondence between them that they had been planning this for some time. In a letter of September 1922 there was reference to the programme du cours pour missionnaires that would go together with the existing curriculum (“notre programme“, which referred to colonial science), supplemented by current medicine, history of evangelisation methods and psychology, applied to the education of children. The intention was to have the missionaries receive one extra year of training in order to give them a real scientific and practical background: “If they agree to sacrifice one year of apostolate this would be in view of a truly solid scientific and practical training.“[33] A number of congregations were positive about this type of training, although there were a number of complaints and uncertainties with regard to founding a general educational course. The Jesuits thought the curriculum too general in intent and too specifically intended for the Congolese situation. After some negotiation and lobbying, in which Ladeuze participated, the coordinating committee of missionary superiors did consent.[34]

The rector of Leuven University was apparently not opposed to such an initiative, although he did emphasise to De Jonghe that everything would have to be feasible, also financially. It was not the first time that De Jonghe found himself in this situation; he was also involved in plans to start anthropological training in Leuven. The key factor in finally deciding against teaching missionary studies at Leuven University is not clear from the few fragments that can be found on this subject in the De Jonghe papers. The only possible explanation that comes out from this exchange of letters is the opposition of Alphonse Broden,[35], the director of the still starting Instituut voor Tropische Geneeskunde (Institute for Tropical Medicine) (at that time still in Forest near Brussels). Asked for his cooperation, De Jonghe is said to have received a principle promise from Broden, who was a well-known figure in scientific circles at the time.[36] However, in a later letter Broden showed some objections to founding a tropical medicine training section in Leuven. It is probable that this was due in part to his desire to protect his own department.[37]

Although this missionary training never came about there was an alternative: Broden had already written to De Jonghe in 1922 with a proposal for the education of missionnaires-brancardiers. As already mentioned, the work continued in this direction. After the approval of the militia law in 1923 De Jonghe and Ladeuze started work on the creation of the curriculum. It was approved by the Minister for the Colonies, Louis Franck, in August. In the following months there were negotiations with various professors but to start with the medical training would be almost exclusively provided by one person, Dr. Dubois, who was recommended to Ladeuze by Mgr. Rutten,[38] the Bishop of Liege. The training was started in the 1923-24 academic year, although the year started late on the third of November due to practical preparations and negotiations. Around fifteen missionaries were enrolled, including a number of Scheutists, a few Jesuits and also 4 MSC: Willem Huygh, Jan De Kerck, Paul Trigalet and Edouard Hulstaert.[39] It is also clear that the last three completed the year. All three of them received a distinction. The centre for nurse-missionaries had a wavering start. In the following years there were no more students but halfway through the thirties this changed and the number of registered students went far above fifty.

However, it was clear that there had been more potential. Although the status of the training remained vague, which is clear from the fact that at one time it could be found under ‘medical training’ in the university curricula brochure and at another occasion under ‘economics’, it was originally the intention to give this very medical education the title of ‘master’s’. At the end of the first academic year there was a discussion in which several professors took part and of which there are several visible traces in the rector’s correspondence. In a letter of 20 June 1924 to Ladeuze, Professor Michotte questioned whether it was necessary to give a master’s degree for a one-year course with an incomplete curriculum at that.[40] Doctor Dubois, who taught almost all the subjects in the first year, declared that he did not want to examine the students on pathology but could just give them a certificate that they had taken the course. He thought the level of the course much too high for them and that they did not have enough prior knowledge, therefore making it impossible to examine them.[41] De Jonghe also took this up in a letter to Ladeuze and said that he had sorted out the matter after a conversation with Dubois and Broden, who supervised the exams as the government representative.[42]

The original concept of a complete area of study for missionaries, rewarded by a ‘real’ degree, was now fulfilled in a different way. A degree of ‘Bachelor in Colonial Sciences’ was created in which the nurse-missionary would follow a number of options in addition to the normal courses. During the first period there was the choice between a limited number of subjects that were part of other disciplines. A subject of De Jonghe’s, Ethnologie et ethnographie du Congo – politique indigène, a history subject Histoire et législation du Congo by P. Coppens, and Organisation industrielle du Congo given by P. Fontainas. Apart from these two subjects, the following were provided on education: Méthodologie générale, taught by François Collard, and Organisation de l’enseignement primaire, taught by Raymond Buyse.[43] Apart from this obligatory package one of the following three topics had to be chosen: Langues coloniales, Géographie physique du Congo or Botanique des plantes tropicales. De Jonghe suggested a further step: the possibility to achieve the title of Docteur en Sciences colonials after a stay of three years in the colony and the defence of a thesis on an adapted topic. This was never put into practice however.[44]

The real impact of the training for the MSC seems to have been limited. The bachelor education, for which a number of non-medical subjects had to be taken, was never really successful. During the peak year of 1938-1939 ten missionaries were awarded this degree. This result was never equalled: the number of graduates constantly fluctuated between zero and ten. Only a handful of MSC achieved the degree over the years. Things were slightly better with the medical training. This could be expected because of the accompanying exemption from military service. However, the number of people that completed the training fluctuated considerably, there can be no definite number given. The only conclusion that can be drawn is that both training programmes gained in popularity during the second half of the thirties. This was the busiest period of participation at the MSC as well. It is no coincidence that this was also the period in which the Catholic missions in the Belgian Congo flourished.

2.1.2. Home education

The missionary’s preparation for their work in Africa remained essentially a matter for the congregations. In relation to this it can be asked how this took place in the congregations that were active in the MSC mission area. The information available on this is very scarce. Generally, it can be said that there were no strict rules for education and that education was in no sense required. For the majority of these congregations there are only indications that future missionaries were housed together during a certain period, in the nineteenth century tradition of being isolated from the outside world. This was, for instance, the case for the Daughters of the Precious Blood, who had a central house in Holland from 1891 where a noviciate was organised. The Brothers of the Christian Schools were probably an exception as they were specifically a teaching order, with systematic training in a teacher training college.

To illustrate this: even an outspoken and large missionary congregation like Scheut kept to the classical division. An information brochure from 1925 states: “The trainee missionary first has a noviciate year in Scheut. During the noviciate the scheutists receive their first training, wholly based on obedience and following Jesus Christ. … Great emphasis is placed on the supernatural in everything: devout piety, independent strength of character, unwavering love for the call and congregation, all encompassing “brotherly love”. After the noviciate the vows are made and the mission country is made known. In principle, they then stayed in Belgium for another six years in order to complete the usual two years of philosophy and four years of theology in Leuven. The brochure stated that, once arrived in the mission area, the missionary spent a year at the central post where he would “acquaint himself further with the language” and was taught the rest of the practical matters.[45] As an extension of what was the case in the African Seminary, the Scheut missionaries already received training in Chinese and Congolese languages in Belgium.[46] The entrance requirements for the candidates were not very high: they had to have completed their studies successfully. However, “(…) If there was anything lacking in this regard but he was accepted to study philosophy in his diocese – if he had applied for this – then he may still have the chance of also being accepted by us.”

2.2. The education of the MSC

According to Honoré Vinck, these conclusions largely correspond with the accepted practice of the MSC.[47] The large majority of the MSC working in the Belgian Congo had not received any more education than the aforementioned philosophical and theological training (the normal priestly training). Of those who worked in the Belgian Congo and were still living at the time of my research, to my knowledge only one possessed a university degree: Frans Maes, who had a Bachelor in Education.[48]

2.2.1. Philosophical and theological training

An aspect that is hard to grasp is the influence of the philosophical and theological training of the MSC on their positions concerning missionary work, being a missionary, Africa, the Congolese and everything to do with their future. The MSC organised their own education. This happened in two steps. In the first phase, the aspiring missionaries spent some years in Gerdingen in the province of Limburg, where the congregation had a training house. They received two years of philosophical training and the first year of their theological education. Subsequently, the students moved to Heverlee near Leuven, where they received three more years of theology. The curriculum (the Ratio studiorum) consisted of a number of subjects, although none of these paid any specific attention to foreign cultures. According to Vinck, educational theory and psychology were only studied in a very limited fashion. The vast majority of the curriculum consisted of theological and philosophical material. A course on ethnology was written by Edmond Boelaert but was certainly not used before the end of the 1950s.[49] Boelaert had already taught classes on ethnology when he was in Belgium, such as in the autumn of 1948. They cannot have been systematically organised courses, however, considering that he never stayed in Belgium for long.[50] Information about the Congo and about missionary life was chiefly an extracurricular activity, given during the activities organised by the community.

Classroom front view

The community life in the training house is perhaps best shown through the chronicles kept by the students. These chronicles were summary reports of the most important events in the monastery or training house. They were published under various titles (Kronijk, Kronieken, Uit ons Leuven) in magazines that the students made and distributed themselves. In Bree the magazine was called De Vloed (‘the flood’), in Leuven De Toekomst (‘the future’). The ‘chronicle’, usually to be found at the back of the magazine, was almost always signed with a pseudonym, its’ tone always flowed well and it briefly sketched the events organised, those that had taken place, who had died and was buried, who had visited, who had been appointed, etc. In the first issue of De Toekomst (1927), for example, it was stated: “10 August: Opening of the missiological week, scholars were present from all countries. The papal nuncio opened the first meeting.“[51] Whether or not many MSC aspirants were present was not mentioned. Later, active participation in this event was reported: “Missionary work finds eager students at our school, to such an extent that a number of them went to the AUCAM to brave the conferences of Dr. Rodhain from Brussels about ‘La situation médicale au Congo’ and of Mr. Olivier Lacombe from Paris about ‘La spiritualité Hindoue’.“[52] In another article about missionary action, another aspirant, Joris Vlamynck, mentioned the AUCAM (Academica Unio Catholicas Adjuvans Missiones), which was more or less connected to student life and the university.[53] He found that in student associations there was too little attention for the M.V.S. (Missiebond Vlaamse Studenten – Mission Union of Flemish Students), the academic mission union of which professors were also part: “The number of members, 400 in 1935 went back to 200 in 1937. Too small a percentage of the 1 600 Flemish students at the College of Higher Education in Leuven“. He was apparently more enthusiastic about the AUCAM about which he said: “Against the pernicious influence of many modern theories in the scientific milieu, the AUCAM is looking for a way to enter that world and to break the inaccessibility of ‘scholarly’ heathenism and its prejudices.”

Although Vlamynck considered the working and action of AUCAM fairly extensively, he gave no further indications concerning the possible participation of MSC in this organisation. There are, however, some indications that this was the case in the second half of the 1930s. In June 1935 it was stated that “Brother Van Kerckhove, using the lessons he had taken with P. Charles, S.J., spoke to us about ‘The goal of the Church and the essence of missionary work’” and two years later the mission club was divided into an ethnological and a missiological department, in which the recently published missiological articles were discussed. During the school year 1935-1936, there were suddenly huge numbers of enrolments for the courses at the university missionary centre. At the start of the school year it was noted in the report that good organisation would be needed because “(…) half the students would become soldiers and would have their hands full“. However, during November it was announced there would be no festivities on the occasion of the Mgr. Verius day, “because of the pressures involved in attending university.”[54] That year there were indeed a record number (17) MSC Members enroled for the courses.[55]

From the magazine chronicles it further appears that initially a missionary only came by ocassionally to talk about the Congo, sometimes with a film or slides. In 1930 the chronicle writer remarked: “19 May: Understandably enough we welcomed the conference with light images that Father Lefèvre came to give us about our Congo mission – everything about the mission awakens our interest and this also brought immeasurable satisfaction.”[56] There was a great need and demand for information about the future place of work in the Congo. Later, this need also appeared sporadically in the records. In February 1932 the training house in Leuven was visited by a number of missionaries who were on a holiday to the motherland. The chronicle reported: “To our great joy, Father Yernaux arrived here very early. We lived with the ‘charcoal artist’ in Mondombe, we heard about the hard ‘labour’ of the development and establishing of the mission post, of the great expenses and hardships, etc.; We got to know the great heart of ‘Fafa Joseph’ and many a wise lesson for later, among others about our contact with the whites, good confirmation of one of our previous lessons from the mission club.”[57] It was phrased even more strongly in 1945: “On 10 (October, JB), Fr. Moeyens, recently returned to the Congo, gave us a captivating talk about the Watuzi tribe in Rwanda (where he had spend some leisure time); he also spoke to us, as a person with true knowledge, of ‘our’ blacks (those of our Mission) and the depopulation of the Congo. It is useful to state how much such conferences are favourable to the missionary spirit of the Scholastic, which is too long frustrated of the good influence emanating from the direct relations with out dear Missions and those returning.“[58] Here, of course, there was an allusion to the war circumstances, which had reduced the contact between Belgium and Congo to a minimum. The need for more information about the future workplace was also expressed at other times. From the second half of the 1930s, the number of meetings increased considerably and in 1950 Father Standaert, when looking back on the period, noted that: “Ample use is also made of the retired missionaries. Too much sometimes, because our own activity is sometimes forgotten.“[59] After the Second World War, the colleagues were still called on to contribute to the meetings regularly. A report of the mission club from 1948 reported: “This year we were often given the opportunity to hear holidaying missionaries, among others Fr. Van Linden, Fr. De Rijck, Fr. Meeuwese, Fr. Wauters, etc. Others gave us studies about missionary work, Fr. Hulstaert, Fr. Geurtjens, Fr. Boelaert, etc. The striking highlight was reached this year on the grand mission day with the staging of the mission play ‘Under the Cross of Tugude’ by Fr. Boelaert and with the striking lecture of Fr. Jan Cortebeeck about the scholasticate and Mission’.”[60]

That same Jan Cortebeeck also wrote the foreword to the text of Boelaert’s play, which was published in 1930 by Davidsfonds as the first part of a new series of children’s books. The tone and style of Cortebeeck’s writing, though a barely concealed attempt at mission propaganda, also illustrate well what the missionaries thought about the mission activity: “For you, youths, this missionary life is easier to understand than for the old. You have a young, fresh, spring soul that can sympathise and empathise with ambitious, cheerful, daring, creative spirits, who can carve from a rough stone artwork which experts will regard with admiration. A missionary is such a daring force. Going to unknown, foreign lands, not knowing what one will find there except many miseries not yet taken into account, to live there away from all the comfort of modern European civilisation, this European civilisation where nothing is left to coincidence, where there are no unforeseen circumstances and requirements, where all the needs of the spirit can be met with the greatest ease, where there is no more distance, transport no longer necessary, where it suffices to lie, in a comfy chair and to turn a button to see and hear the enchantment of all arts, all over the civilised world.”

The valiant and heroic element was still at the fore here, together with an aversion towards the ‘modernisation’ that society was undergoing at home. With the presupposition that the missions should thus be different, the question of how the missionaries saw this was of course raised: “He dreams of a reversal of the heathenism and sees his primitives, his country and people recreated into a cultured society of people singing peace without even one single police helmet; of laughing prosperity and restful sufficiency, where every family can live well on the fruits of their own labour, in their own house, on their own estate without import or export; an ideal society where one is more sustained from lively, fresh virtues than from bread and where one doesn’t see or know money: a society with no banks and no poverty, where one lives happily and dies happy and goes straight to Heaven.”[61] This message directly criticises the situation as it was being experienced in Europe. For many people in the period in which this text first appeared, this type of discourse would probably have been experienced as a way out of the bad economic crisis they were confronted with. It is not coincidental that ‘banks’ and ‘money’ were named as things to be avoided in a new, ideal society.

Boelaert’s own play, which he had already written in 1926, is vaguely situated in the MSC mission in Papua New Guinea and is characterised by heroism and drama. ‘Tugude’ is about a missionary who is confronted with a number of local customs which he opposes, quite correctly according to the story. The local tribes wish to hold a dance party behind his back. The missionary knows that these dance parties always end in tribal quarrels and fist fights. He tries to stop the various tribal chiefs from taking part in the party but does not succeed. When the party does end in murder and manslaughter the missionary is threatened with being held guilty of the death of one of the women who must be avenged. Thanks to the level-headedness of the missionary, and the sacrifice of the good, converted primitive, he manages to retain his life. In this the local people are described as primitives who can be dealt with because the white missionary is more intelligent and can confuse them by his faster reasoning. The indecisiveness and inconstancy of the local chieftains is heavily emphasised. The self-sacrificing love, taught by the missionaries, is victorious and eventually converts all the natives.

The chronicles and similar columns only make up a small section of the scholasticate periodicals. The principle part was made up of articles that were almost exclusively written by the students themselves and which dealt with a variety of theological, philosophical, moral or social subjects. The tone of these articles was generally very serious. The subjects were mainly the extension of the training itself and so they were often theological or philosophical in impact. The choice of certain topics makes it clear that the students themselves chose the topics and that the content of these periodicals was not being dictated from above, although they regularly contain devout professions of thanks to superiors. However, it is likely that this would be an established practice in such an environment. The articles are an interesting way of finding out more about the points of view and ideas that the future missionaries generally had, especially concerning missionary activity and colonisation. Before going further into the content it is best to further situate the articles and the periodicals in the context in which they appeared. They are, after all, closely attached to the particulars of the ‘mission club’.

2.2.2. The Mission Club

The specific missionary aspect of the education of the young religious students was covered in a number of meetings which were organised around specific topics. This was the so-called ‘mission club’. According to the information available there must certainly have been two clubs in the MSC: one in the scholasticate in Leuven and one in that of Bree, where the philosophical training of the missionaries took place (but on which much less information is preserved). The name ‘mission club’ is perhaps representative of the atmosphere in which this training aspect took place. From the descriptions that may be found in the MSC Archives they appear sometimes to be meetings of adventurously inclined youths, who came to listen to exciting stories about exotic situations. It will become apparent later that the voluntary and free character of this initiative still has to be somewhat interpreted. In any event, other ‘clubs’ also existed within the community in the training house, such as the ‘Thomas club’, a philosophical study club.

Meetings of the mission club began to be organised (again) after the First World War. On this occasion one of those taking part wrote: “At the start of the school year 1918-1919 we began with setting up the previously flourishing ‘mission club’ again. This has always had as a goal (and it shall, if it pleases God, continue to strive to meet its goals with diligence) the holy fire of the mission, to awaken the extremely mighty help of the apostolate and to enrich our future missionaries with everything that may be of use to us later in the mission”[62] From a ‘report of the meetings’ that was made about this time: “Every Tuesday after the walk we should come together to talk about the interests of the club, or to attend a lecture, or to practice the English language, since this is so widespread and always comes in useful to the missionary.“[63] Apparently, not everything went without difficulties. At the start of the new academic year in October 1919 the composition of the new club was recorded in the minutes. There were at that moment twelve members, including Hulstaert (who was the secretary) and Boelaert. In December 1919 the reporter finished his report with the announcement: “After the lecture it was also suggested by our chairman that an association for prayer and fasting should be made of the mission club.” This proposal would also be accepted promptly. The mission club remained for the following years a combination of religious exercise and passing on of know-how. In the following years the subjects covered included the following: ”The attitude of the Catholic missionaries towards the Protestants”; ”An interesting study of ethnology, a subject that is relatively neglected by us”; ‘The Pygmies‘; ‘Conference by Fr. Hulstaert on the Dutch East Indies; ‘The mission thought’; ‘Malaria fever’; ‘The actions of the Protestants in their missions’; ‘The use of catechists‘.

At the start of the academic year 1923-1924 the club was again suspended, only to start up again after the first term of the following academic year. The activities and the rhythm of the meetings were perhaps very dependent on other preoccupations of the Fathers. Besides this it indicates that, certainly in this period (early 1920), the club was not really a priority. Again in the early thirties the club went into hibernation from time to time. As has been reported earlier, there were years when only the (scarce) missionaries who were resting were called upon, those who had time enough to recount memories of their time on the missions. During the academic year 1934-1935 the secretary noted after the December meeting: “Until May A. Cortebeeck addressed the monthly meeting of the club. In rather interesting stories about the Philippines he presented us time and again with real missionary life.” After several years of very low activity from 1930 to 1935, the situation improved again. At the start of the academic year 1936-1937 two sections were set up, one ethnological and one missionary. It is no coincidence that the secretary that year was Albert De Rop, a man who was very interested in ethnology.[64] There were probably also more theologically inspired members of the mission club, though it is not possible to find out right away who these were. It is noteworthy that there was indeed a greater interest for specifically Congolese themes to be seen in the lectures that were organised from now on. The division into two sections clearly only lasted one year but the interest in the ‘ethnic’ Congolese culture remained prominent afterwards in the meetings. In later years there would be another division, at a time when the MSC were also active in Brazil. During the war years the activities remained reasonably constant, even though it was sometimes impossible to meet together because of the war activities[65] and there were also complaints that the interest of the Fathers themselves was not always what it should be.

Framework

The contents of the subjects that were reported in the periodical of the scholasticate and the subjects reported in the reports of the mission club overlap. The lectures that were held and the subjects that were discussed in the mission club were very often supported by the writings of aspirant missionaries. On the basis of the contributions that were mentioned in the mission writings, some additional nuances can probably be displayed regarding the contents of the articles. The manner in which the subjects treated were assimilated and even simply what had been remembered, is expressed better in these writings. These are notes which form a sort of minutes of the meetings of the mission club, and as such had an archiving function within the group, but which certainly did not have an officially representative function with respect to the outside world or to any higher authority. Only during two years (during the Second World War) did the superior set his signature under the reports, from which it can be deduced that some form of control existed. Apart from this one instance there is nothing in the way of compulsion or checking from above to be detected concerning the meetings, nor in the periodical put together by the students. The situation in which these writings came to exist was naturally rather specific: this was a relatively small group of people who had a great deal of contact with each other within a closed community outside the context of these specific meetings. There certainly existed a degree of social control and there must also have been the selection of information and data, including those concerning the future activities of the missionaries, though this mostly happened in an implicit way.

In any case, within the mission club and outside it there was close contact with the Fathers, including those who came from the missions. From the manner in which the visits of ‘real’ missionaries, those who had already been abroad, were spoken of, it can be deduced that the students looked up to these people and although they did not perhaps glamorise them or hero-worship them, they did admire them and took them as examples. The mission club or the events that were organised by the club (Mission Sunday, ‘Vérius memorial’) were excellent opportunities to “learn something new”. A large part of the activities were probably not at all experienced as a duty by those involved, but as something much more logical or automatic. Again, keeping reports would probably have been interpreted in this way. Honoré Vinck, who was secretary of the mission club immediately after independence, put it as follows: they did it because it was part of being a serious association and they wanted to be taken seriously. If they had not kept reports, the superior would perhaps have made some remark about it, not because of the contents of the reports but certainly because it would have been a form of laziness.[66] The qualification ‘moral duty’ seems to apply here. It indicates that the disciplining of the future missionaries was done comprehensively in a very subtle and implicit manner.

The mission club was part of the new world which one entered as an aspirant, a world with its own rules and fixed patterns, which one did not question. This is supported by the fact that, once the missionaries could leave for the Congo, they were given a task to do and sent to a place to do it by their superiors. They were to take on this task without complaint. Father Frans Maes, whom I interviewed, was an exception in the sense that he knew that he would get an educational task in the Congo and therefore had been obliged to take a degree in education. However, that was also determined by his superiors, “(…) because the Government required a qualification to be able to teach“. That also was just accepted and done.[67] Maes finally ended up in a school in the mission post of Flandria (Boteke), where a degree was not at all necessary, because it was a private school. This caused Maes to remark: “So I really could have gone to the Congo two years earlier!” In any case, he seemed rather unimpressed by what he had learnt during his educational course. To the question of whether he had found much use for his theoretical education, he answered that otherwise he would not have been able to set examinations. He had learnt that in Leuven.[68] Again, from talking with other missionaries it is apparent that the future destination of the aspirants, both functional and geographic, was mostly decided by their superiors.

Activities

The idea of the mission club was based, according to the MSC themselves, on two pillars: a spiritual, religious perception on the one hand and a more intellectually moulding activity on the other hand. The two were somewhat intertwined. It was important not only to collect information about the region, the people and mission activities but also to lay a sound spiritual and moral foundation. In fact, it would be more correct to say that the activities of the mission club were on three different levels: moulding, devotion and propaganda. Before going more deeply into the contents of the moulding, the first two elements will be discussed because they were regarded by the missionaries themselves as at least as important in the preparation of the aspirants.

It is clear that the spiritual element always remained an integral part of the meetings. The duties of prayer and religiosity were repeated at almost every meeting. “Some exercises of virtue and prayer were imposed at the attention of the missionaries, the missions and the primitives. In this way we work on our own perfection. All members should pray a rosary each month for the fellow members.”[69] Every month there was a prayer task; more specifically prayers were dedicated for a certain goal or a certain person (or persons). Expressions such as these (but with changing subjects) are to be seen regularly in the reports: “The speaker ended with a call to pray well for the intention of the month that our Congo mission should not fall prey to Protestant disunity.” The required devotion, religiosity and piety naturally showed through in the reports themselves, depending on the dedication and diligence that the reporter of the day showed. The war years represent a high point (probably not coincidentally).

It is not an unfounded or ahistorical interpretation when we speak here about the religious and spiritual element in the training of missionaries. This is shown by the remarks that were made during the first meeting at the start of the academic year, such as this remark from 1943: “Following our tradition the President wants to talk about the aim and the spirit of our club and also what place these must take in our life at the scholasticate. The aim is to advance mission knowledge, but above all mission love. For the men of Leuven the romantic vision of the missionary life has faded to make way for the conviction that the missionary life is a true life of sacrifice … What is demanded of a missionary besides prayer and sacrifice? Father Yernaux shared the following with our chairman: A great love of one’s neighbour is more necessary than mission study, so that the ingratitude of the negroes does not put you out of action. Also a reasonable knowledge of French, so as to be always able to get on with the white colonists.”[70] Prayer and devotion were elements that were systematically present and that are repeatedly mentioned in the reports. It is of course in the nature of missionary life that there is a place for religious aspects. During the reading of the different reports, however, an image appears in which religious inspiration seems to be rather essential, at least in the interpretation of the various authors. This inspiration also seems to be independent of the longing for romance or heroism, though it cannot be denied that the two were very often intertwined. The fact that ‘sacrifice’ seems to be a central concept in the life of a missionary may have something to do with this. This is discussed further in the section about the role of the missionary.

Picture of a Batswa village