Reshaping Remembrance ~ Language Monuments

1.

1.

The year 1975 was declared Language Year by the South African government, and 14 August was declared a public holiday in celebration of the centennial of the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners (Society of Real Afrikaners) so that ‘people all over the country can celebrate the birthday of Afrikaans’.[i] On that day, the festivities commenced at the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria. In memory of the eight founding members of the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners, eight ‘language torches’ departed from the Voortrekker Monument to all corners of the Republic and to South West Africa (Namibia). In the following months, Afrikaans newspapers regularly covered the ‘Miracle of Afrikaans’, reporting on local festivities and publishing articles on the history of the Genootskap. One lasting outcome of this enthusiasm was a little-known language monument unveiled in East London on 9 September as part of a local language festival. It bears the words of a third-rate Afrikaans poet, C.F. Visser: ‘O, Moedertaal / O, soetste taal, / Jou het ek lief / bo alles’ (O mother tongue, O sweetest tongue, You I love above all). The unveiling of the huge language monument outside Paarl had been scheduled for 10 October, Kruger Day, for practical reasons: the weather was better in October than in August – the middle of the rainy Cape winter.

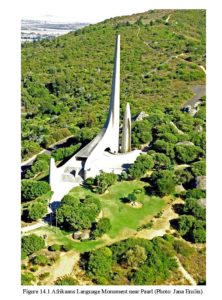

The erection of the language monument in Paarl had been in preparation since the 1940s. In 1965 a Monument Committee approved a design for a language monument by the Pretoria architect Jan van Wijk. It was to be a modernist concrete structure in the style of Le Corbusier, and according to the brief given by the committee it was to be visible from the main road and blend in with the landscape. The latter requirement was to be achieved by mixing crushed Paarl granite with the concrete. The report of the commission of experts describes the visual experience of the monument in terms of a future promenade architecturale (Le Corbusier):

The designer makes the visitor climb up stairs to reach the threshold of the entrance […] The visitor reaches a fountain and, having enjoyed the sound of the water, turns right and proceeds to the open space of the inner court. In our view, this is one of the most attractive concepts of the whole design. From this point there will be a splendid view of the main column and the buttress supporting it, an opportunity to pause for a while on one of the granite benches that will be provided and to enjoy the panoramas in the different points of the compass. […] Next to the main column, with a view on what the designer calls the ‘magical influences of Africa’, stands the smaller column that must symbolise our becoming a republic. […] A basin at the foot of both columns effectively connects them […]. We are also particularly struck by the three domes in the inner court which must remind us of the non-white elements. The inclined buttress of the inner court is reminiscent of another African motif, the ruins of Zimbabwe. We find the juxtaposition of these symbols of Africa particularly successful.[ii]

The iconography of the monument is based broadly on statements made by two important Afrikaans authors. The conspicuous main column is based on a statement made by C.J. Langenhoven in Bloemfontein in 1914, in a speech for the Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns (South African Academy for Science and Art). Langenhoven describes the development of Afrikaans as a line reaching for heaven, a parabola of linguistic achievement. Following in the footsteps of the poet N.P. van Wyk Louw, the horizontal dimension must express the connection of a ‘lucid West’ and a ‘magical Africa’. The ‘non-white’ origins of Afrikaans are also referred to in the form of a small column, dedicated to Malay, on the stairway to the monument.

For some Afrikaners, like Loots, the founder of the Monument Committee, these symbols were an impermissible overstepping of racial boundaries. In his view, this reference to the non-white contribution to Afrikaans was ‘unnecessary’. In protest, he even threatened to disrupt the festivities with violent acts of sabotage.[iii]

2.

Early in the morning of Friday 10 October, on Kruger Day, forty thousand Afrikaners started gathering around the monument on a mountain outside the small town of Paarl. According to reports in the Cape daily Die Burger a festive mood prevailed, stimulated by the brass band of the Department of Prisons and the military band of the Cape Coloured Corps. Special provisions had been made for coloured people.

Although the terraces that had been ‘reserved’ for them were not entirely full, they nevertheless played a part in the proceedings. The Primrose Malay Choir in particular was a huge success in the amphitheatre at the foot of the monument. The choir was accompanied by a bass, guitars and ukuleles. Nine Air Force jets blazed a blue, white and orange trail – the colours of the flag – while two Afrikaner scouts hoisted the flag. At ten o’clock that night the celebrations culminated in the arrival of the language torches:

There was a stir among the crowd when hundreds of Voortrekkers [Afrikaner boy scouts] with burning torches started moving up a Paarlberg shrouded in darkness towards the amphitheatre. Contingents of eight with flags smartly handed over the route torches to the Premier [John Vorster] […] For each torch, the Navy Band played a fanfare that had been specially commissioned […] After the torch procedure, Mr Vorster delivered his address, after which the descendants [of the members of the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners] helped to light the main torch and to declare the monument officially unveiled.[iv]

In conclusion, eight cannons fired a salvo. The eight language torches and eight cannons referred to the eight men who had founded the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners. Those present were probably well aware of this, in view of the constant stream of articles in the press and the attention devoted to it in Afrikaans-medium schools.

The Language Monument was the last of a series of Afrikaans monuments that marked the political position of Afrikaners in the country since the end of the nineteenth in South Africa was celebrated.

3.

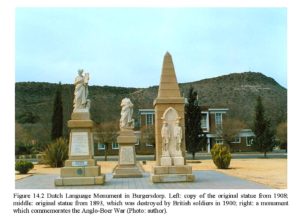

The series of Afrikaans monuments started approximately in 1893 with the unveiling of the first Language Monument in Burgersdorp in the Eastern Cape. Erected there to celebrate the Dutch language, it was even a world première: the world’s first stone memorial to a language. A more common tribute would be a series of classical works or a large dictionary.

The Burgersdorp Language Monument marks the early phase of the language struggle of Afrikaners to have ‘high Dutch’, the same language as that of the Netherlands, recognized as a junior partner alongside English. The actions promoting ‘Patriots’, a variant of the Cape Dutch vernacular that was propagated as the official language by the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners, still occupied the second place. Moreover, these actions stagnated during the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902).

The nature of the Burgersdorp festivities was rather different from that of the 1975 festival, which was run tightly by a South African police colonel. The occasionally chaotic Burgersdorp festival lasted five days. There were processions of farmers on horseback, picnics, official dinners and endless speeches. It was a sort of village fair. The centrepiece of all activities was ‘Oom’ Daantjie van den Heever, a convivial fellow who took a salute in mufti, but wearing a helmet of the Free State Artillery. After the parade he took part in a race with ‘several ladies’, which he lost. A separate race was organized for ministers of the church.

There even was a publicity fiasco. Some days before the start of the actual festival, a ‘scandal and farce burlesque’ was staged in Venterstad. This advance festival was held to collect funds for the official festival in Burgersdorp. The children were lavishly entertained in the hall of the Dutch Reformed Church and rewarded with English prize books. In the evening, an ‘Amateur Entertainment, in support of the Taal Festival Fund’ took place, presided by Oom Daantjie. For three hours the audience was entertained with English items. Oom Daantje’s own children also participated. True, the last item on the programme was a reading of a poem by the Dutch poet Nicolaas Beets.

However, after singing the nationalist Afrikanerbond song, the proceedings were closed with the singing of ‘God save the King’. Die Patriot and De Zuid-Afrikaan, Cape newspapers that supported Afrikaner nationalism, cried shame on it.[v]

Figure 14.2 Dutch Language Monument in Burgersdorp. Left: copy of the original statue from 1908; middle: original statue from 1893, which was destroyed by British soldiers in 1900; right: a monument which commemorates the Anglo-Boer War (Photo: author).

The Burgersdorp Language Monument was unveiled a few days later in the presence of the leaders of Afrikaner nationalism, the Cape politician ‘Onze Jan’ Hofmeyr and the author-journalist S.J. du Toit. Following the classicist tradition of giving abstract concepts a female shape, this language monument was a comely young girl of whom rumour had it that Oom Daantjie’s daughter had sat for it. Cradled in her left arm the statue bore a tablet with the inscription: ‘Vrijheid voor de Hollandsche Taal’ (Freedom for the Dutch language). Unfortunately this elegant statue did not grace its pedestal for long. In 1901, it was smashed by English troops and the pieces were transported to King William’s Town, a few hundred kilometres from Burgersdorp. After the war, in 1908, the English colonial regime donated a copy of the statue, which was mounted on the empty pedestal. When the decapitated and armless statue was uncovered on a rubbish tip in the 1930s, it was erected diagonally behind the copy.

In 1893 the Afrikaner nationalists were still a politically subordinate and, in comparison with the English rulers, a vulnerable group of underdeveloped rural people taking their first hesitant steps to getting themselves organised. Initially there was no agreement about the language which should be used as the language of the people. It was only during the Second Language Movement, after 1905, that the enthusiasm to have Afrikaans recognised surpassed that favouring Dutch. The First and Second Language Movements had propagated Afrikaans as a characteristic of an Afrikaner identity and wanted it to occupy a central position in the fight for political power. ‘Afrikaans was made in South Africa to suit our African circumstances and way of life; it grew up together with our national character; it is the only bond that holds us together as a distinct nation; the only characteristic of our people’, said the author Langenhoven.[vi] Language was the starting point on the road to realising fully-fledged citizenship. Language activism also envisaged economic benefits. General Herzog foresaw that in the bureaucracy and the press more jobs would become available for white Afrikaansspeakers once a better position for Afrikaans had been gained.[vii]

In 1925 Afrikaans was recognised as an official language of the Union of South Africa. This Afrikaans was still a nascent language, based on the Paarl variety of the Cape Dutch vernacular. In order to make this language more acceptable to the bourgeoisie, it was embellished with borrowings from Dutch. Not everyone was satisfied with the result. The Transvaal language advocates Eugène Marais and Gustav Preller regarded this type of Afrikaans as too close to the Paarl (Western Cape) form whereas they had hoped it would be closer to the Dutch varieties of Cape Dutch. For instance, they bemoaned the fact that imperfect tense forms had virtually disappeared from the new standard Afrikaans. A literature also had to be built up[viii]. In Van Wyk Louw’s view, a high-quality literature was the justification of national independence. Good poetry was a matter of national policy.[ix] Even in the 1940s language users were still uncertain about the language norms of Afrikaans.[x] The next target in the language struggle of the Afrikaners was equality with English. This became a possibility only after the National Party came to power in 1948 and made language equality within the civil service compulsory, and also introduced Afrikaansmedium education for Afrikaans-speaking white and coloured people. Beyond these fields, Afrikaans was too far behind English.

Even after 1948, English remained the language of choice in the cities, in the business world and especially among black people. The preference of blacks for English was on the one hand due to the fact that since the nineteenth century they had been almost exclusively educated in English under the English colonial regime and (partly as a result of this education policy) because English was regarded by black people as the main gateway to Western knowledge and economic progress. In this regard Afrikaans was less significant; besides, it carried the stigma that it was used by white officials to implement the policy of apartheid. Consequently, Afrikaans was able to maintain its claims to equality with English only for as long as black people remained excluded from political power and Afrikaners constituted the majority within white politics.

4.

The language monument in Paarl was elected to commemorate the founding of an association that promoted the recognition of a variety of the Cape Dutch vernacular and the establishment of an Afrikaner national consciousness in which language was an important symbol of identity. This Afrikaner Nationalist sentiment existed in the planning of the Monument Committee right from the outset. According to the competition of 1965, the monument had to ‘symbolise the miracle of our cultural and political growth. […] the first Afrikaans Language Movement that started here in Paarl was therefore much more than just a language movement; it was a movement for the cultural, political and religious liberation of the Afrikaans section of the population’.[xi]

The Republic Column of the Monument that shared the basin with the Language Column expressed these sentiments. In the iconography of the monument the roots of Afrikaans were ascribed to the rational powers of the ‘lucid West’. In the monument, ‘magical Africa’ is a continent that has to be guided by Afrikaans and by the Republic of South Africa. The report by the commission of experts of the competition mentions ‘the role of guidance and assistance that our country must play on the continent’.[xii]

The Language Column and Republic Column are positioned in the monument in a colonial opposition to the horizontal components, which are intended to represent Africa. According to this symbolism an originally rational Afrikaans language and a nation of European origin want to give guidance to an irrational and passive Africa.

Ten years later, when the unveiling took place, this pipe-dream of 1965 had long proved to be an illusion. In 1975 almost all of Africa had been decolonised. In 1974, Angola and Mozambique were the last to gain independence. A few months before the unveiling of the monument South African troops had started an ultimately abortive campaign against the Marxist MPLA, which was about to take over the government of Angola. Internationally, South Africa was becoming increasingly isolated because of its apartheid policy, while the black population was less and less willing to tolerate white minority rule.

In the meantime the government continued to pursue equality between Afrikaans and English in education. This had consequences for black schools only much later. Although it was decided in 1965 that from the last year of primary school Afrikaans would be used on an equal basis with English as the medium of instruction in black schools outside the homelands, this policy was never implemented in Soweto, for example. There it was only introduced in 1974. In 1975, however, black school boards in Transvaal instructed their schools to ignore this policy. One important reason for the resistance was that a greater role for Afrikaans as the medium of instruction was regarded as an excessive burden on pupils who were already finding it difficult to receive their education in English. Instead of acquiring subject knowledge, they would lose even more time learning an additional language of instruction. However, the deputy minister of Bantu education, Andries Treurnicht, stuck to his guns. ‘In the white area of South Africa, where the government supplies the buildings, gives the subsidies and pays the teachers, it is surely our right to determine the language dispensation’. Tensions surrounding the use of Afrikaans existed in Soweto long before 16 June 1976, when the black pupils in Soweto rebelled.[xiii]

The speech made by John Vorster when the Language Monument was unveiled contains traces of a sense of being under threat and isolated. At the start of his speech he turned on critics in Africa, Europe and America who alleged that the Afrikaners were merely temporary residents in South Africa, remnants of colonialism. The existence of Afrikaans proved, in his view, precisely that Afrikaners were entitled to be in South Africa because Afrikaans had originated in Africa. ‘All responsible people in the world and in Africa irrevocably accept that we have the right to be in South Africa and form part of Africa. […] We can celebrate tonight knowing that we are recognized and that our title deed to be here is written in Afrikaans’.[xiv]

The second part of the articles in Die Burger in which the unveiling of the Language Monument and Vorster’s speech were reported on, was printed next to a photograph on which eight (!) white men kneel before the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin. Given the symbolic overload of the ceremony, the impression is created that this juxtaposition was not coincidental.[xv]

The racial policy of the National Party government carried much of the responsibility for the isolation of institutionalised Afrikaans. Afrikaans-language universities were not accessible to coloured speakers of the language. The Afrikaans media presented Afrikaans mainly as a ‘white man’s language’ and defended the apartheid regime. The special editions of Die Burger and Paarl Post published on the occasion of the unveiling of the monument contained few or no references to coloured speakers of Afrikaans, whereas they accounted for almost half of the total number of native speakers and an article was devoted to the much smaller ‘Jewish contribution to Afrikaans’.[xvi] The government did not exactly deal leniently with critical authors either.

In the Language Year, shortly before the unveiling of the monument, the Afrikaans poet Breyten Breytenbach was arrested on suspicion of terrorism. On 13 October, two days after the big day in Paarl, a report on the Language Monument and a report on Breytenbach’s wife, who had filed a request for a visa in Paris to visit her husband in prison, shared the front page of Die Burger.

5.

After 1994 the Language Monument initially became the target of loathing of the abuse of power by Afrikaners. Breytenbach’s labelling of the monument as a concrete penis in The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist was repeated with variations. Some critics even thought that they could detect the stink of urine at the base of the language column. The curves on the horizontal part of the monument which were supposed to symbolise Africa were described as ‘little turds’.[xvii]

The new government put forward a proposal to declare the Language Monument a monument to all languages in South Africa. The attempts to profane the monument or to change the original meaning by decree were short lived. Year after year the subsidy for maintenance costs was simply paid out.

In 2009 the Language Monument has become a popular attraction for foreign tourists. Only one third of the visitors were South Africans; two thirds came from abroad.[xviii] The monument has developed into one of many enclosed (and therefore safe) tourist enclaves in South Africa[xix]. There are helpful elucidations of the symbolism of the Monument in various foreign languages. Afterwards the visitor can have coffee and buy souvenirs, most of which are the usual collection of ethnic art and T-shirts.

Information on Afrikaans is hard to find. The Language Monument prefers to advertise the ‘spectacular sunsets and sundowners’ rather than the Afrikaans language [xx]. Like so many others in the new South Africa, the monument has been repackaged. It is now a Paarl version of Table Mountain or Cape Point, more a natural phenomenon for the avid tourist gaze than a place of historical significance.

NOTES

i. Die Burger, 14 August 1975.

ii. 2 Language Museum, Paarl, Dokumente oor Taalmonument, Assessoreverslag van prysvraag, 21 January 1966.

iii. Language Museum, Paarl, Dokumente oor Taalmonument, Die Afrikaanse Taalmonumentkomitee, Minutes of 18 July 1975.

iv. Die Burger, 11 October 1975.

v. D.H. Cilliers, Albert se aandeel in die Afrikaanse beweging tot 1900. Burgersdorp, Burgersdorpse Seëlkomitee 1982, 72-82.

vi. C.J. Langenhoven, Versamelde werke. Cape Town: Nasionale Pers 1938, Deel xii , 371.

vii. J.B.M. Hertzog, Die Hertzogtoesprake, Deel 3, April 1913-April 1918. Johannesburg: Perskor 1977, 264-265. Hertzog was a former Boer general and an Afrikaner nationalist politician.

viii. S. Swart, ‘An spect of the roles of Eugène Marais and Gustav Preller in the Second Language Movement c. 1905-1927’, http://academic.sun.ac.za/history/downloads/swart/eugenemarais.pdf.

ix. N.P. van Wyk Louw, Versamelde prosa, Vol. I. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau 1986, 18-25, 44-48.

x. A. Deumert, Language Standardization and Language Change. The Dynamics of Cape Dutch. Amsterdam: John Benjamins 2004.

xi. Taalmuseum, Paarl, Dokumente oor Taalmonument, Die Afrikaanse Taalmonumentkomitee, Boukundige prysvraag, 12 April 1965.

xii. Taalmuseum, Paarl, Dokumente oor Taalmonument, Assessoreverslag van prysvraag, 21 January 1966.

xiii. J.C. Steyn, Tuiste in eie taal. Die behoud en bestaan van Afrikaans. Kaapstad: Tafelberg 1980, 255-305.

xiv. Die Burger, 11 October 1975.

xv. ibid.

xvi. Bylae tot Paarl Post, 15 August 1975; Afrikaans 1875-1975, special supplement to Die Burger for the unveiling of the Language Monument on 10 October 1975.

xvii. Case No: 1995/08 SABC – Agenda, Die Taalmonument; Afrikaner-Kultuur (AKB), D.J. Malan en Andere (Complainant) vs. SABC (Respondent). Broadcasting Complaints Commission of South Africa:

http://www.bccsa.co.za (viewed 15 September 2007).

xviii. Language Monument, Paarl, Visitor statistics, April 2005 to March 2007 (with thanks to Gerda Odendaal, student of Afrikaans and Dutch, University of Stellenbosch, for obtaining the statistics).

xix. Cf. A. Grundlingh, ‘A Cultural Conundrum? Old Monuments and New Regimes: The Voortrekker Monument as Symbol of Afrikaner Power in a Postapartheid South Africa’, in: Radical History Review 81 (Fall 2001), 95-112.

xx. Language Monument Restaurant, http://www.tourismcapewinelands.co.za/za/guide/6de,en,SCH1/

objectId,CTR4201za,curr,ZAR,season,at2,selectedEntry,home/home.html (viewed 15 September 2007).

References

Archival sources

Language Monument, Paarl, Visitor statistics, 2005-2006.

Language Museum, Paarl, Minutes of the Afrikaans Language Monument Commitee and other documents about the Language Monument.

Publications

Case No: 1995/08 sabc – Agenda, Die Taalmonument; Afrikaner-Kultuur (akb), D.J. Malan en Andere (Complainant) vs. SABC (Respondent). Broadcasting Complaints Commission of South Africa: http://www.bccsa.co.za.

Deumert, A. Language Standardisation and Language Change. The Dynamics of Cape Dutch. Amsterdam: John Benjamins 2004.

Die Burger, July-October 1975.

Geldenhuys, D.J.C. Uit die wieg van ons taal. Pannevis en Preller met hul pleidooie. Johannesburg: Voortrekkerpers 1967.

Grundlingh, A. ‘A Cultural Conundrum? Old Monuments and New Regimes: The Voortrekker Monument as Symbol of Afrikaner Power in a Postapartheid South Africa’, in: Radical History Review 81 (Fall 2001), 95-112.

Hertzog, J.B.M. Die Hertzogtoesprake, Deel 3, April 1913-April 1918. Johannesburg: Perskor 1977.

Langenhoven, C.J. Versamelde werke. Part x and xii. Cape Town: Nasionale Pers 1938.

Louw, N.P. van Wyk. Versamelde prosa. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau 1986.

Paarl Post, Supplement, 15 August 1975.

Steyn, J.C. Tuiste in eie taal. Die behoud en bestaan van Afrikaans. Kaapstad: Tafelberg 1980.

Swart, S.S. ‘An Aspect of the Roles of Eugène Marais and Gustav Preller in the Second Language Movement c. 1905-1927’,

http://www.academic.sun.ac.za/history/downloads/swart/eugene-marais.pdf.