Abstract

Abstract

The irregular use of katakana has been analysed mainly in descriptive terms and is often considered to be a device for creating homonyms or communicating emotions (See Ogakiuchi, 2010). This chapter examines the irregular use of katakana notation from the perspective of relevance theory. Unlike previous studies, which have focused on the images and emotions the katakana notation system is said to communicate, this chapter focuses on concepts communicated by the use of words when they are written in katakana rather than other usual notations. I show that the irregular use of katakana is just one of many devices used for highlighting ad hoc concepts that can be found universally and should be analysed in a wider context than describing the functions of this notation,which is unique to Japanese. I argue that a cognitively grounded relevance theoretic account, in particular the notions of ad hoc concepts and metarepresentation, enables us to provide an explanation for observations made in previous studies.

The paper concludes that emotions attributed to the use of katakana and the homonyms which katakana notation appears to create can be explained in terms of repeated metarepresentation of ad hoc concepts and attributed thoughts communicated by the concepts.

Introduction –The Japanese Writing System

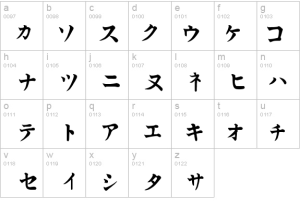

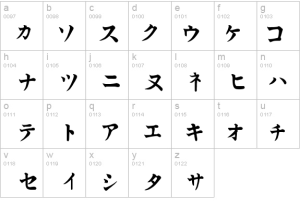

The Japanese writing system uses three different types of notation. The first is kanji, which is logographic. Each kanji character has a “meaning” and is used for conceptual words. There are also two alphabet systems, hiragana and katakana. Hiragana is phonographic and used for particles, connectives, and other “function words”, as well as being used by children (and adults) when they do not know which kanji to use. Katakana is also phonographic and is mainly used for loan words, onomatopoeia, and the names of animals, species, flowers, etc. It is convention that all three notation systems are used as required. Example (1) demonstrates this:

(1) ジョンの 庭にネコが 入ってきた.

John no niwa ni neko ga haitte kita

John GEN garden LOC cat SUB entered

“A cat came into John’s garden.”

In (1), two conceptual words,“garden”and “enter”, are written in kanji: 庭 and 入, respectively. Hiragana is used for particles,“no” (の) and “ni” (に), part of verb conjugation (ってきた), and the subject marker“ga” (が). Although they are conceptual words, katakana is used for “John” (ジョン) and “cat” (ネコ) as John is non-Japanese and “cat” is the name of an animal.

The choice of notation system is based on this convention and one’s ability – if one does not know or remember how to write a certain kanji, one might choose to write the word in hiragana or katakana. This is particularly the case for children and in hand-written texts. This paper does not aim to analyse these cases, where choice of notation is based on personal abilities. Nor does it deal with cases where katakana notation is used as it is expected to be. Instead, this study will focus on cases where the use of katakana cannot be explained in terms of personal abilities or preferences. In particular, I shall focus on cases in which katakana is used where it is not expected or not because of personal preference/abilities. A particular focus will be placed on correlations between choice of notation and construction of ad hoc concepts, where the use of katakana seems to trigger concept adjustment. See “Fukushima”in (2)[i]:

(2) チェルノブイリからフクシマへ「同じ道たどらないで」

Chernobyl kara Fukushima e “onaji michi tadoranaide”

Chernobyl FROM Fukushima LOC “same road follow-NEG-IMPERATIVE”

From Chernobyl to Fukushima: “Please do not go the way we did”

(Sekine 2011)

“Fukushima” is the name of a town and, normally, it is written as 福島 in kanji. However, in (2), it is written as フクシマ in katakana, and it seems to communicate more than just a name. What does it communicate? How is it different from “Fukushima” written in kanji? In following sections, I will first look at how katakana notation has been dealt with in previous studies and then present an alternative account from the perspective of relevance theory.

Literature Review

The recent increase inapparent irregular uses of katakana has been analysed in descriptive terms and there are two main points that are often discussed. First, there seems to be a preferred argument that the use of katakana in some cases indicates the word in question is independent of the original lexical item and should be treated as a homonym (e.g. Narita and Sakakihara,2004; Norimatsu and Horio, 2006; Okugakiuchi, 2010). Second, some uses of katakana are often considered to communicate some kind of emotion (Norimatsu and Horio, 2006; Sugimoto, 2009; and, to some extent, Okugakiuchi, 2010). The shape and the look of katakana characters are often cited causing these issues. Let us examine Okugakiuchi (2010) closely, as his account seems to be the most comprehensive and tries to account for not only what katakana notation communicates, but also how katakana notation comes to motivate meaning changes.

Okugakiuchi (2010) examines a range of katakana uses from the perspective of Cognitive Linguistics (cf. Yamanashi, 2000) and claims that katakana notation is a method of creating new words. He argues that the images and the visual characteristics associated with the katakana writing system could explain linguistic meaning, based on an assumption that the notation itself is part of “meaning” and leads the reader to the different “images”, hence motivating the difference in meaning. He lists “foreign”, “cold”, “stuck-up”, “modern”, “fashionable”, and “sharp” as components of the images of katakana.

While Okugakiuchi (2010) puts forward an interesting account of the apparent irregular use of katakana in cognitive terms, it gives rise to a number of questions. First, it is not clear what he means by “meaning”. He repeatedly claims that the visual characteristics of katakana lead to different “images”, which motivates a difference in meaning. This suggests that a difference in appearance indicates a difference in meaning. It is true that when written in different fonts, in any language, you might get a different “feel” from the text. For example, if the notice “DO NOT DISTURB” is written in Comic Sans, one might not take it as seriously as when it is written in Times New Roman. However, the question should be whether this “feel” is linguistically encoded or not, rather than how it is perceived by the readers. This is an important question for Okugakiuchi, as it is related to his explanation of how katakana can create homonyms by separating an expression from the original word. Okugakiuchi reasons that compared to kanji, which is logographic, katakana is “weaker in meaning” (2010, pp.82–83) as it is phonographic and is thus more likely to become separated from the original meaning of the word written in kanji. However, it is not clear what he means by “weaker in meaning”. Does he mean that“meanings” have varying degrees of strength? Is it a matter of linguistic encoding, or is it about inferential aspects of “meaning”? Moreover, he seems to overlook the importance of contextual assumptions. The supporting evidence for his claim is an observation that if a word,“koen”, is written in katakana, it is impossible to determine the intended concept as it simply is a phonetic representation of the word – it could be a PARK, a LECTURE, or a PERFORMANCE. In contrast, if it is written in kanji, the reader will have no problem recovering the intended concept: if it is written as 公園, then it would be “park”, and if it is written as 講演, then it would be “lecture”.

Okugakiuchi (2010) is right and, of course, if you see a word written in katakana on its own, out of context, it is near impossible to determine which meaning has been intended. In that sense, the use of kanji provides more of a “clue” for the reader. However, Okugakiuchi (2010) seems to have overlooked the fact that utterances are usually produced in a context and the reader will be able to interpret the utterance without any particular difficulties. For example, if I email my friend, “if the weather is nice tomorrow, let’s have a picnic at ‘koen’”, “koen” would not be interpreted as “lecture”, even if it is written in a phonographic notation. It would, instead, be interpreted as “to have a picnic in a PARK”. This inference is based on existing assumptions about picnics, normal behaviour in lectures, and the weather. In other words, the contribution that the use of kanji makes is to provide extra contextual information rather than to strengthen the meaning of the word.

Second, there is the fundamental question of what the image of katakana is. Okugakiuchi (2010) says that the use of katakana adds meaning to the original, and the meaning should be something that suits the image of katakana. We have seen the images associated with katakana he listed (“foreign”,“cold”,“stuck-up”,“modern”,“fashionable”, and “sharp”). When something (e.g.koji, meaning construction work) does not fit in with the image, he argues, it cannot be written in katakana. While this argument might capture one’s intuition about this particular word, “koji”, it still raises a few questions. For example, what are these “images”? Are there any more components in addition to what he has listed (“foreign”, “fashionable”, etc.)? What if koji is used in a context where construction work is fashionable? By what means does something become acceptable for use in katakana?Okugakiuchi’s (2010) analysis does not provide answers to these questions.

Relevance Theory and Key Concepts

The lack of explanation for the apparent irregular use of katakana might be because previous studies have described the functions of notation systems rather than the concepts the notation is used to encode. In the following section, I shall give an overview of how acognitively grounded theory of communication, relevance theory, deals with concepts and linguistic expression, and present an alternative view on the relationship between choice of notation and construction of ad hoc concepts.

Relevance theory – an outline

Relevance theory is a cognitive theory of human communication and aims to explain how the hearer recovers intended meaning based on the evidence provided by the speaker.[ii] The central claim is based on the definition of relevance and two principles that govern human cognition and communication. Relevance is defined as a function of cost (processing effort) and effect (positive cognitive effects – contextual implication, contradiction, and elimination of existing assumptions, and strengthening of existing assumptions) (Wilson and Sperber, 2002,p252-253):

Relevance of an input to an individual:

“a. Other things being equal, the greater the positive cognitive effects achieved by processing an input, the greater the relevance of the input to the individual at that time.

b. Other things being equal, the greater the processing effort expended, the lower the relevance of the input to the individual at that time.” (Sperber and Wilson, 2002,pp.252–253)

Sperber and Wilson (1995, 2002) claim that human cognition has evolved in such a way that we tend to work towards maximizing the effects and towards maximizing relevance by aiming for the most cost-effective processing. Based on this fundamental assumption, they propose the Cognitive Principle of Relevance:

Cognitive Principle of Relevance

“Human cognition tends to be geared to maximisation of relevance.” (Sperber and Wilson, 2002, p.255)

Note that there can be no guarantee of maximum relevance. Instead, when the speaker produces an utterance, the hearer is entitled to expect a degree of optimal relevance (Sperber and Wilson, 1995).

Communicative Principle of Relevance

“Every act of ostensive communication communicates a presumption of its own optimal relevance.” (Sperber and Wilson, 1995, p.260)

An ostensive stimulus is optimally relevant to an audience if:

a. It is relevant enough to be worth the audience’s processing effort;

b. It is the most relevant one compatible with communicator’s abilities and preferences.

(Wilson and Sperber, 2002, p.604)

The presumption of optimal relevance is only applicable for ostensive communication, where the speaker’s informative and communicative intentions are obvious. In other words, accidental communication (e.g. you having a runny nose tells your audience that you have a cold) is not ostensive communication and thus does not carry the presumption of optimal relevance (Wilson and Sperber, 2002:255).

“Ostensive-inferential communication

a. The informative intention:

The intention to inform an audience of something.

b. The communicative intention:

The intention to inform the audience of one’s informative

intention.” (Wilson and Sperber, 2002, p.255)

An utterance is a form of evidence which is linguistically encoded. Sperber and Wilson (1995) consider that utterance interpretation includes not only linguistic decoding but also inference. When an utterance is produced, the hearer performs inferenceson conceptual representations which the grammar delivers. This conceptual representation is used as an input to the inferential phase of utterance interpretation. The presumption of optimal relevance justifies the hearer following the most cost-effective interpretation path (the relevance theoretic comprehension procedure: “follow a path of least effort in computing cognitive effects: test interpretive hypotheses in order of accessibility, and stop when your expectations of relevance are satisfied”(Wilson and Sperber, 2002: 262)).

Note that this relevance theoretic comprehension procedure does not apply only to interpretation of the utterance as a whole. The hearer’s search for relevance starts at the very basic level of identifying the intended concepts that are components of the explicit contentof the utterance. In other words, even lexical-pragmatic processesare motivated by relevance, and the hearer looks for the interpretation that matches his/her expectations of relevance. Wilson (2004, p.354) argues that the relevance theoretic approach to utterance comprehension implies that one cannot expect literalness:

“[T]here is no presumption of literalness: the linguistically encoded meaning (of a word, a phrase, a sentence) is no more than a clue to the speaker’s meaning, which is not decoded but non-demonstratively inferred.”

In other words, the hearer uses the linguistically decoded meaning as a departure point, and builds on it to recover an explicature, and seeks for implicature until s/he reaches an interpretation that matches his/her expectation of relevance [iii]. Once s/he gets to this point, s/he stops and goes no further. The recovery of the intended concept is also guided by relevance. Let us see how it actually works. Example (3) illustrates this point:

(3) [Peter told Mary that his niece has passed the bar exam]

Mary: She has got a brain!

In (3), like in any other ostensive communication, Peter will expect Mary’s utterance to be optimally relevant. In addition to this, he expects Mary’s utterance to be relevant as a response to the information he has just given to her(that Peter’s niece has passed the bar exam). If the intended interpretation is literal, then the utterance would not achieve relevance (i.e. yield no cognitive effect), as we all have a brain, and the information that she has a brain (if taken literally) does not change anything in Peter’s cognitive environment. However, in this case, her utterance “she’s got a brain!” will certainly yield some interpretation that achieves an optimal relevance, together with existing assumptions Peter can access. For example, he might have an assumption that in order to pass the bar exam, one must be very intelligent, or one must work very hard. Following the path of least effort, Peter will recover the intended concept of “brain”, not the literal BRAIN, but something different (but related), such as “an intellectual ability that enabled her to pass a notoriously difficult exam”. The intended concept is not encoded, but isconstructed in context, based on assumptions about the encoded concept. In relevance theory, this type of concept is called ad hoc concept.

Relevance theory, concepts and concept adjustment

Relevance theory takes a Fodorian view of linguistic semantics and considers that words encode “mentally-represented concepts, elements of a conceptual representation system or ‘language of thought’, which constitute their linguistic meanings and determine what might be called their linguistically-specified denotations” (Wilson 2003, p.344) (see also, Sperber and Wilson, 1995; Wilson and Sperber, 2002; or Carston, 2002). An encoded concept works as an address to the intended atomic concept, and it enables the hearer to access information about the concept:

“The content or semantics of this entity is its denotation, what it refers to in the world, and the lexical form that encodes it, in effect, inherits its denotational semantics. This conceptual address (or file name) gives access to a repository of mentally represented information about the concept’s denotation, some of which is general and some of which, such as stereotypes, applies only to particular subsets of the denotation.” (Carston, 2010, p.9)

Note that there is no one-to-one correspondence between words and concepts. As is often pointed out, the communicated concept is often different from what is encoded by the word in question. For example, we could communicate many concepts by the use of a verb “open”:

(4) Alfie can now open the stair gate.

(5) [Teacher says to class] Please open page 532.

(6) John opened a bottle of wine.

(7) Sainsbury’s opens at 11am on Sundays.

(8) I need to open a savings account for Alfie.

(9) Open Microsoft Word and open the document called“lexical pragmatics”.

The above examples are only some of the actions that can be denoted by “open”. The reader will have to determine, via inference, which concept is intended. This illustrates how much richer our conceptual system is than what appears at the linguistic level, and how lexical items are “adjusted” in the interpretation process. The fact is, we can never communicate what we intend solely by means of encoded elements. This is called linguistic underdeterminacy, and it requires a number of inferential processes to determine what the explicit content of the speaker’s utterance is:

(10) He is too old.

In order to determine the proposition expressed by the utterance in (10), the referent of “he” needs to be assigned and the constituent that does not appear on the surface of the grammatical sentence should be supplied (enrichment, “too old for what”). This pragmatic enrichment will then help the hearer determine the intended concept for “old”, since if the referent of “he”is “too old to use a highchair”, then the possible age would be around three or older, when toddlers stop using highchairs, but if it is “too old to play in the U–21 football team”, then it will be any age over 22. This again shows that there is a discrepancy between the encoded concepts and the concepts the speaker intended to communicate. Wilson (2003) says that the aim of lexical pragmatics is to account for this gap. Particular attention has been paid to lexical approximation (i.e.broadening), as illustrated in (11), narrowing, as illustrated in (12), and metaphorical extension, as illustrated in (13) (see, for example, Carston, 2002, 2010; Wilson, 2004; Wilson and Carston, 2006, 2007;Sperber and Wilson, 2006).

(11) I shouldn’t have had a large glass of wine on an empty stomach.

(12) [In a pub] Let’s get some drinks, shall we?

(13) John is Mary’s ATM.

“Empty stomach” in (11) does not literally mean a stomach that contains nothing. It means, instead, a stomach that contains less than the ideal amount of food to stop the speaker from getting drunk. “Drink” in (12) only highlights a specific member of the subset of concepts that could be encoded by DRINK, and it is normally interpreted as “alcoholic drinks”. Metaphorical extension is a radical case of category extension, and in (13), “ATM”can be seen as representing the category of “place for withdrawing cash”. As Wilson (2004) says, these processes have been analysed separately as distinct processes. However, these are just descriptions of the outcomes, not the process itself, of lexical adjustment, as Carston (2010, p.13) points out:

“The denotation of the pragmatically inferred concept is narrower or broader (or both) than the denotation of the lexical concept which provided the evidential input to its derivation. The idea is not that there are two distinct processes – of making narrower and making broader – but rather a single overall pragmatic adjustment/modulation process with these various possible results.”

Every time a word is used, the concept encoded by the word provides a blueprint for the interpretation process. Based on this blueprint, the hearer recovers a new concept that is either narrower or broader than the encoded concept via a pragmatic process of lexical adjustment. After all, natural language does not correspond to the language of thought but provides a basis for building up representations. These new concepts that are constructed only for single occasions of use are called ad hoc concepts. An ad hoc concept is constructed as a one-off and does not constitute our language of thought (i.e. is not established as a fully-fledged concept that can be encoded by a lexicon). It is used to represent an entity that is not encoded but accessible in our conceptual system (Carston, 2010, p.15):

“Strictly speaking, these new, possibly one-off, ad hoc entities are not concepts, although they have the potential to become concepts, that is, stable, enduring components of Mentalese. Nevertheless, even in their preconceptual manifestation, they can make a contribution to structured propositional states, specifically explicatures, alongside fully-fledged concepts (whether lexical or ad hoc) and play a role in warranting certain implications of the utterance.”

When the communicated concept is an ad hoc concept, the word the speaker chooses is used interpretively in order to metarepresent whatever s/he intended to communicate. In other words, by mentioning a particular linguistic item, the speaker is trying to guide the hearer to a specific conceptual representation that is not encoded by the expression but can be highlighted/ activated by the use of the word. It can be a concept that has a narrower/broader category than the encoded concept. Or, it could be an ad hoc concept that denotes a context-specific entity. The lexical comprehension is guided by expectation of relevance – the hearer will construct an ad hoc concept as part of an explicature that will achieve an optimal relevance. Let us see how this can be applied to a specific example. Recall example (13), where an ad hoc concept needs to be constructed for “ATM”. Rather than considering the literal meaning of ATM, the hearer would interpret the utterance as “Mary spends John’s money”or “Mary takes advantage of John’s generosity”. However, the use of “ATM” in this utterance is not something that is already in the hearer’s conceptual system. It is context specific and a one-off. In other words, it is ad hoc. The speaker “mentioned” this word in order to metarepresent the intended concept. Note that there is a varying range for this ad-hocness, as Carston (2010) points out. For example, calling someone an “ATM” or describing having an “empty” stomach might not be too creative and thus one might have the ad hoc concept in the conceptual system more or less firmly, while there will also be more creative and very context-specific ones. After all, all communicated concepts are ad hoc to some extent. The point is, however, that lexical comprehension involves pragmatic processes of lexical adjustment and in some cases requires the construction of ad hoc concepts.

Ad hoc concepts and katakana notation

So far, we have seen how concept adjustment and linguistic expressions are treated in relevance theory. The question now is, exactly what happens if katakana is used where it is not supposed to be?Consider example (2) and examples (14) to (16) below. These examples contain the word“Fukushima”, the name of a town located in the north east of Japan. Generally, town names are written in kanji and “Fukushima” is normally written as 福島. However, in the cases below,“Fukushima” has been written in katakana as フクシマ:

(2) チェルノブイリからフクシマへ「同じ道たどらないで」

Chernobyl kara Fukushima e “onajimichitadoranaide”

Chernobyl FROM Fukushima LOC “same road follow-NEG-IMPERATIVE”

From Chernobyl to Fukushima: “Please do not go the way we did”

(Sekine 2011)

In this example, “Fukushima” does not merely refer to the town. It seems to include a wider range of information related to FUKUSHIMA, the encoded concept. Similar cases are found in many examples:

(14)フクシマ後の世界の原子力産業

Fukushima-go no sekai no genshiryoku sangyo

Fukushima-after GEN world GEN nuclear industry

“International nuclear industry after the disaster at Fukushima.”

(Johnson 2011)

(15) 軍用ロボ、フクシマに投入 米ハイテク企業が名乗り

Gunyo robo, Fukushima ni tonyu.

military robot Fukushima DAT throw-in

Bei haiteku kigyo ga nanori.

U.S. HIGH-TECH company NOM bid

“Military robots to be sent to Fukushima, a U.S. high-tech company has offered.”

(Komiyama 2011)

(16) 世界の原発大国、フクシマを助けて

Sekai no genpatsutaikoku, Fukushima o tasukete.

World GEN nuclear-countries, Fukushima ACC help

“‘To major countries with advanced technology for nuclear power – please help’, Fukushima.”

(Asahi Shimbun Digital 2011)

In these examples, “Fukushima”is written in katakana rather than conventional kanji, and whatever is intended by the author does not seem to bejust the encoded concept of FUKUSHIMA (i.e. the town).What the author intends the reader to construct, based on the encoded concept, is not something the reader has had in his/her memory as an existing concept. In other words, the intended concepts are ad hoc concepts rather than encoded concepts. “Fukushima” in katakana contributes to the recovery of the ad hoc concept FUKUSHIMA*, which becomes part of explicature of the utterance. The process is based on the encoded concept FUKUSHIMA, and it would be interpreted as “the tragedy and disaster in the Fukushima area”, “people affected by the disaster in Fukushima”, or something similar. In other words, FUKUSHIMA* is an ad hoc concept and metarepresents thoughts the authorintends by using katakana, rather than attempting to linguistically express ineffable concepts.

Note that this does not necessarily mean the ad hoc concepts FUKUSHIMA* in (2), (14) to (16) are all identical. In fact, the reader would recover different ad hoc concepts, similar to ones below, from the use of “Fukushima” in (2) and (14) to (16)[iv] :

(2’) Area and people affected by the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear plant.

(14’) What happened at the Fukushima nuclear plant during the 3/11 earthquake and tsunami.

(15’)The Fukushima nuclear power plant.

(16’) The Fukushima nuclear plant and area and people in Fukushima

This suggests that whatever the author intended to communicate, it is an ad hoc concept that denotes something that is adjusted from the encoded concept, and the role of katakana in these cases seems to be to highlight the intended ad hoc nature of the concepts, to make them stand out from other possible members of the set of concepts that a word could encode.

Interestingly, katakana is often used when we write Japanese words that are frequently used as loan words in other languages:

(17)日本でスシを食べるための確実に押さえるべき10のステップ

Nihon de sushi o taberu tame no

Japan LOC sushi ACC eat purpose GEN

kakujitsuni osaerubeki 10 no suteppu

Certainly ensure-should 10 GEN steps

“10 steps for eating sushi in Japan”

(Gigazine 2010)

(18)「『サケ・ソムリエ』なんて言うんじゃないよ。サケは日本のものだ。ワインの世界から言葉を借りてくる必要がどこにある?」

‘“Sake-Sommelier ”nante iunjanai yo.

SAKE-SOMMELIER such say-NEG SF

Sake wa nihon no mono da.

Sake TOP Japan GEN thing SF

Wine no sekai kara kotoba o karitekuru hitsuyou ga doko ni aru?’

Wine GEN world from words ACC borrow necessity SUB where LOC exist?

“Don’t call me a Sake-Sommelier.’ Sake is Japanese. Why do you need to borrow a word from the wine world?”

(Noge 2012)

(19)ジュードーから柔道へ

Judo kara judo e

Judo from judo to

“From judo to judo.’”

(Sports Navi Plus 2013)

In examples (17) to (19), katakana is used for concepts that would normally be written in hiragana or kanji: “sushi”in (17) is written as スシ rather than 寿司, “sake” in (18)is written as サケ rather than 酒, and “judo” in (19) is written as ジュードー rather than 柔道. Recovery of all of these concepts includes broadening processes and the author intends the reader to construct ad hoc concepts that become part of theexplicature of the utterance. Based on the encoded concepts SUSHI, SAKE, and JUDO, the reader would recover ad hoc concepts of SUSHI*, SAKE*, and JUDO*. So, exactly what sort of ad hoc concepts are intended? The contexts for (17) to (19) all involve some sort of international aspect. (17) is a guide for foreign tourists who want to experience sushicuisine in Japan. Example (18) is a quote from an American sakespecialist. In this interview, he particularly objects to the idea of calling sakeexperts “sake-sommeliers” like a wine expert in French. Example (19) is particularly interesting – it is a title of blog entry which describes the return of Japan as winners in the world-class Judo tournament. In this example, kanji (柔道) is used when the word in question is used to refer to original judo (or traditional judo in these examples), while katakana (ジュードー) is used for the word “judo” after it became known internationally. In all these examples, katakana is used in order to trigger an interpretation of concepts as the world, not the Japanese,is thought to perceive them. In other words, the intended concepts SUSHI*, SAKE*, and JUDO* metarepresent conceptual entries as they are perceived by the global community.

So far, I have only examined cases of Japanese words used in international contexts – loan words or the disaster which was reported worldwide. However, this type of katakana use is not limited to these cases. Example (20) is about differences in personality between girls and boys. Katakana is used instead of kanji in order to narrow down the denotation of original lexicon where the thought that is metarepresentedis only specific parts of the encoded concept.

(20) [Mothers are discussing differences between having daughters and having sons]

女の子は演技する?女の子は小さい頃からオンナ?男の子は優しく素直で単純?男の子はいつまでもコドモ?

Onna no ko wa engisuru?

woman GEN child TOP perform?

Onna no ko wa chiisai koro kara onna?

Woman GEN child TOP little period from woman?

Otoko no ko wa yasashiku sunao de tanjun?

Man GEN child TOP gentle honest and simple?

Otoko no kowaitsu made mo kodomo?

Man GEN child TOP when till child?

“Are girls good actresses? Are girls women from a very early age? Are boys gentle, honest and simple? Do boys stay like a child forever?”

(Yomiuri Online 2011)

In (20), “onna”(woman) is written in katakana as オンナ, rather than in kanji as 女. Similarly, “kodomo”(child) is written in katakana as コドモ, rather than in kanji as 子供. The intended concept for “onna”,WOMAN*, contains only specific parts of the encoded concept WOMAN. It may include information about stereotypical characteristics of WOMEN, such as “women like to go shopping”, “women gossip” or, even worse, “women are manipulative”. It may also include other stereotypical views of women, such as “women like to care for others” or “women are good at multi-tasking”. However, the intended, ad hoc concept WOMEN* does not include other information, such as “ female human being above certain age”. Similarly, the intended concept for “kodomo”(child) is also more than the encoded concept CHILD. In this case, it does not include “young” or “small”. Instead, it only includes stereotypical characteristics such as “children like to play outside”, “children love toys and cartoons”, or, even, “children don’t think about consequences”.

So, katakana can be used to represent a particular concept which is related (or even part of) to the original concept. The question now is why katakana is used this way more often than other notation systems. Maybe the nature of katakana notation will explain this function of katakana. Historically, katakana notation has been used for onomatopoeic expressions and loan words. It would be safe to say that onomatopoeic expressions are an interpretation of sound/noise in the world and that loan words are an interpretation of phonological properties of words that do not originate in the language in question. In other words, the primal function of katakana is to metarepresent –katakana is an alphabet system for metarepresentation[v]. Authors use katakana to attribute the conceptual representation to others at a lexical level, and thus contribute to the recovery of an“adjusted” concept.

This analysis also explains why the use of katakana often communicates“emotions”, as pointed out in previous studies (e.g. NorimatsuandHorio, 2006). In her analysis of metalinguistic negation as an echoic use, Carston (1999, p.12) argues that an echoic use of language involves “ metarepresenting and attributing an utterance (or part thereof) or a thought (or part thereof), and expressing an attitude to it (broadly, either endorsement or dissociation)”. Metarepresenting and attributing a thought are what is happening with the use of katakana we have seen in this chapter. If an echoic use involves metarepresenting and attributing thoughts and expressing an attitude to it, then it is not surprising that the use of katakana in this way could also express an attitude to the metarepresented thoughts. The author could, for example, justify his/her own emotion by endorsing the metarepresented thoughts, hence emphasizing the emotion. In fact, it does not matter who the thoughts are attributed to. Thoughts need not be attributed to anyone real at all. The fact that thoughts appear to be attributed to someone else is enough to enable the author to distance him/herself from these thoughts and express his/her attitude towards them.

Earlier, we examined Okugakiuchi’s (2010) claim that katakana notation is a device for creating homonyms. His central claim was that when written in katakana, the meaning can more easily be separated from original meaning written in kanji, especially since (1) as a phonographic system,katakana-written words carry meanings “more weakly”, and (2) the visual characteristics of katakana evoke different images which motivate the difference(s) in meanings. Although I did argue against his homonym analysis, he is right that katakana-written concepts can sometimes be seen as independent lexical items. See (21) and (22), where both KUSURI and KEITAI can be seen as new lexical items that encode new concepts, KUSURI* and KEITAI*:

(21)クスリでちょっと遊ぼうよ

Kusuri de chotto asobo yo.

kusuri with little play SF.

“Let’s have fun using some drugs”

(Mie Prefecture 2008)

(22)スマートフォンの“ケータイ化”を進める、各社の夏商戦戦略

Smart phone no ‘keitai-ka’ o susumeru,

Smart phone GEN mobile–change’ ACC promote

kakusha no natsushosen senryaku

companies GEN summer-sales trategy

“Summer sale strategies of each company – changing smart phones into ‘mobiles’”

(Sano 2008)

In (21), “kusuri” is written in katakana as クスリ, rather than in the conventional kanji as 薬. The encoded concept of KUSURI is “medicine” or “drugs”, with no negative connotation. However, what is intended by “kusuri” in (21) is “illegal drugs”. While “kusuri” in katakana can still be used to deliver KUSURI, it isKUSURI* (illegal drugs) that the reader would be likely to access first. Similarly, in (22), “keitai” is written in katakana as ケータイ, rather than in the conventional kanji as 携帯. While the encoded concept of “keitai” in (22) is KEITAI (mobile/carrying), the concept that stands out from other possible interpretations when written in katakana is KEITAI* (a mobile phone). In particular, KEITAI* seems to include encyclopaedic information such as “the device everyone has” or “the device that is the key item in the current consumer market”, which is not included in the original, non-shortened KEITAIDENWA (MOBILE PHONE). Does this mean that Okugakiuchi is right and katakana is a device forcreating new lexical items?

It is true that there are cases where katakana-written items become so routinized that they now appear to be homonyms to the original lexical items. KUSURI* in (21) and KEITAI* in (22) are the obvious examples. However, katakana notation does not necessarily lead the item to become an independent lexical item. It would be more logical to think that the ad hoc concepts written in katakana could sometimes become routinized and thus established as an independent lexical item, rather than that katakana notation is adevice creating new words. When the “metarepresented” concept is used over and over,it then becomes a case of “dead” metarepresentation (as in “deadmetaphor”).

Ad Hoc Concepts and Highlighters

So far, I have shown that the apparent irregular use of katakana can be explained in terms of marking ad hoc concepts. I have also explained why katakana is used for writing words expressing ad hoc concepts. This analysis also enables us to explain why katakana-written words can sometimes become an independent word, thus giving an impression that katakana notation is a device for creating new homonyms to original lexicon. What I have not done, however, is to explain why authors “point to” or “highlight” ad hoc concepts by using katakana – not why it is katakana that we use, but why we mark ad hoc concepts in the first place

As we saw earlier, according to the Communicative Principle of Relevance, any stimulus used in an ostensive communication creates a presumption of optimal relevance. In other words, one can assume that there is no unjustifiable processing effort imposed when processing an ostensive stimulus (utterance, gesture, anything that can be used to communicate). If a stimulus is costlier to process, then the hearer will be rewarded with extra cognitive effects. Wilson and Wharton (2006) illustrate how this idea enables us to account for contrastive prosody patterns (from Wilson and Wharton, 2006, p.1568):

(23)

a. Federer played Henman and he be´at him.

b. Federer played Henman and he´ beat hı´m.

In (23), the differences in prosody patterns (the neutral pattern for (a) and the contrastive pattern for (b)) affect the reference assignment of “he”. Under normal circumstances, the preferred interpretation would be “Federer played Henman and Federer beat Henman”, which is what the reader would recover by the use of a neutral prosody pattern in (a). It is obvious that the contrastive pattern in (b) is costlier. However, this extra processing effort is balanced out by increased effect. In this case, the contrastive prosodic pattern will guide the hearer, who is following a relevance theoretic comprehension procedure, to the less salient interpretation,“Federer played Henman and Henman beat Federer”. In other words, contrastive stress in this case is used as a highlighter, which spotlights an intended interpretation. The use of a costlier stimulus is balanced out by this extra effect, which cannot be achieved via any other means without imposing extra processing effort.

If this is the case, switching notation systems where it is not expected would surely cost more processing effort and thus there should be extra effects. And indeed, the use of katakana to mark metarepresented ad hoc concepts seems to play a similar role. Recall the FUKUSHIMA examples. We saw that by using katakana, “Fukushima”can communicate a range of ad hoc concepts:

(2’) Area and people affected by the disaster at Fukushima nuclear plant

(14’) What happened at the Fukushima nuclear plant during the 3/11 earthquake and tsunami

(15’) The Fukushima nuclear power plant

(16’) Fukushima nuclear plant and area and the people in Fukushima

If “Fukushima” is written in kanji, as it conventionally is, the encoded concept FUKUSHIMA (i.e. the town) would be preferred as an interpretation. Of course, the reader might be able to recover these ad hoc concepts above even when it is written in kanji. However, the use of katakana instead of kanji can make it easier for the reader choose the intended ad hoc concept that denotes a specific subset (or a specific (pre)conceptual entity) that can be denoted by the encoded concept. Note that there is potentially an infinite set of entities that can be the intended concept for “Fukushima” and the list above is but a few examples of what it can refer to.

In (17) to (19), we saw that Japanese words that are often used as loan words in foreign languages (“sushi”, “sake”, and“judo”) can be written in katakana and the intended concepts are ad hoc concepts rather than the encoded concepts. We also saw a case, (20), where katakana was used in a case of lexical narrowing. In these cases, again, the role of katakana is to put a spotlight on the intended concept, denoting a specific subset of the category out of the other possible entities and to so balance out the extra processing cost imposed by switching the notation.

Marking ad hoc concepts is not particular to Japanese. The code switching illustrated in (24) and the use of capital letters such as in (25b) can also be used to mark ad hoc concepts:

(24) “They have to ‘sumimasen’ their way through life while biting their toungue [sic].”

(After Hours Japan 2011)_

(25)

a. We’ve had some troubles with our neighbours about car parking.

b. The Troubles in Ireland caused too much hurt.

Ad hoc concepts contribute to the recovery of explicature and hence to relevance by communicating whatever the speaker cannot communicate by using encoded concepts without imposing unjustifiable processing costs. Marking ad hoc concepts using these devices is another way of ensuring that no unjustifiable processing cost is imposed. For example, in (24), the speaker could have chosen the English equivalent“‘excuse me”, etc. Again, however, it may not capture what “sumimasen” can communicate. While “troubles”in (25a) denotes the encoded concept TROUBLE, when “Troubles” is written with a capital T as illustrated in (25b), especially in a context of Ireland, the intended concept is not what is encoded. Instead, the intended concept is the ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland since the 1960s.

So far, we have seen that katakana notation is a way of marking metarepresented ad hoc concepts. As I have just shown, it is not particular to Japanese to mark ad hoc concepts and there are a number of devices a speaker can use to mark ad hoc concepts, including code-switching and the use of capital letters. The choice of devices is up to the speaker – his/her ability and preference. It might be a stylistic choice or it might be restricted by mode of communication (e.g. gestures would only occur in spoken discourse, and katakana would be used only in written discourse). This is in line with the Communicative Principle of Relevance and the definition of optimal relevance introduced earlier. Whatever stimulus the speaker chooses to use in an ostensive communication, the reader can expect it to be optimally relevant. That is, the reader can expect the stimulus to be worth his/her attention and to be the best and most preferred stimulus that the speaker can offer in the particular context.

Conclusion

In this paper, I took observations made in previous studies as a departure point and examined the concepts communicated by the use of words written in katakana, rather than discussing the image of the notation system or emotions that katakana use can communicate. My main claim is that the apparent irregular use of katakana is one of many devices we can use as a highlighter for metarepresented ad hoc concepts. Rather than creating homonyms that are independent of original lexicon, as often claimed in previous studies, the irregular use of katakana notation marks a metarepresentation of an ad hoc concept that is recovered as a result of pragmatic lexical adjustment. As a highlighter, it contributes to relevance by guiding the reader to CONSTRUC Tan intended concept IN CONTEXT rather than retrieving and using, for the interpretation, some kind of basic concept found in the lexicon.

I also showed that when used over and over, katakana-written words can become independent lexical items. This is not because katakana is a device for creating homonyms, as Okugakiuchi (2010) claims. In fact, it does not matter whether it is katakana or any other method that is used to mark metarepresentation. It is more to do with the fact that a particular ad hoc concept is used repeatedly and thus become established as an entity in our mind. In other words, the ad hoc concepts can become established as an independent word when used repeatedly.

It is interesting that there are language-specific and language non-specific highlighting devices. Quotation marks or an equivalent might be universal for literate speech communities, while katakana notation is restricted to Japanese only. The bottom line is, however, that the process is universal and applicable across languages, and a relevance theoretic cognitively-grounded analysis enables us to provide a unified account.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Seiji Uchida, Rebecca Jackson, and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. However, all errors and misunderstandings that may be contained in this paper are my responsibility.

NOTES

[i] For convenience, I have marked the use of katakana in bold and underline when transcribed in the Roman alphabet. This does not mean that I believe bold underlineand katakana have the same function

[ii] Relevance theory conventionally uses speaker’ and ‘hearer’. I will, therefore, follow the convention and use the ‘speaker’ and the ‘hearer’ rather than the ‘author’ and ‘reader’ in this section where I present fundamental notions of Relevance theory.

[iii] The explicit/implicit distinction in relevance theory is slightly (and fundamentally) different from Grice’s distinction between “what is said”and “what is meant” (Grice 1989). In relevance theory, explicature is defined as “an ostensively communicated assumption which is inferentially developed from one of the incomplete conceptual representations (logical forms) encoded by the utterance” (Carston 2002, p.377) and implicature is defined as “a communicated assumption which is derived solely via process of pragmatic inference” (ibid.). See, for example, Carston, 2002, Sperber and Wilson 1995, and Wilson and Sperber, 2002 for detailed discussion.

[iv] Please note that these paraphrases are provided as indication of its interpretation only. In relevance theory, as Carston (2010) explains, ad hoc concepts are considered to be ineffable, and they are not considered lexicalized, nor are they considered fully encoded.

[v] This is not to say thatkatakananotation is the only way to mark metarepresentation. As Uchida (personal communication) points out, other notation systems can be used to mark ad hoc concepts, especially with proper names (cf. え〜ごがく –“Eigogaku”, written in hiragana, thetitle of newsletter for The EnglishLinguistic Society of Japan), or 布恋人 –“Friend”, written in kanji, the name of a bar). The point is, however, that this happens more often with katakana, perhaps because of its original function to mark metarepresention.

References

After Hours Japan, 2011. How will all this effect Japan to reflect…. [Online] Available from http://www.after-hours-japan.com/node/1688?page=1 [Accessed on 22nd October 2013]

Asahi Shimbun Digital, 2011. To major countries with advanced technology for nuclear power – please help’, Fukushima. Asahi Shimbun Digital [Online] 31 March. Available from http://www.asahi.com/special/10005/TKY201103310564.html [Accessed 22nd October 2013]

Carston, R.,2002. Thoughts and utterances: the pragmatics of explicit communication. Oxford: Blackwell.

Carston, R., 2010. Lexical pragmatics, ad hoc concepts and metaphor: from a relevance theory perspective. Italian Journal of Linguistics,22(1),pp.153–180.

Gigazine, 2010. 10 steps for eating sushi in Japan. [Online]. Available from: http://gigazine.net/news/20100223_sushi_steps/ [Accessed on 22nd October 2013]

Johnson, T., 2011. Fukushima-go no sekai no gunji-sangyo. [Nuclear Power Expansiono Challenge]. Foreign Affairs Report [Online] April. Available from: http://www.foreignaffairsj.co.jp/essay/201104/CFR_Update, last accessed on 16 January 2012

Narita, T.and Sakakihara, H., 2004. Gendai Nihongo no hyoki taikei to hyoki senryaku – Katakana no tsukai kata no henka [Writing System and Writing Strategy in Contemporary Japanese : A Change in the Usage of KATAKANA]. Studies in Humanities and Cultures,20,pp.41–55.

Komiyama, R., 2011. Military robots to be sent to Fukushima, a U.S. high-tech company has offered. Asahi Shimbun: Japan [Online] 1 April. Available from: http://www.asahi.com/national/update/0401/TKY201103310637.html [Accessed on 16 January 2012]

Mie Prefecture, 2008. Yakubutsu ranyo boshi nit suite [Preventing drug abuse]. [Online]. Available from: http://www.pref.mie.lg.jp/YAKUMUS/HP/yakuji/yakuran.htm

Noge, Y., 2012. An American Sake-Samurai helps rebuild from the disaster. Nihon KeizaiShimbun: Japan [Online] Available from: http://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXBZO45809320W2A900C1000000/ [Accessed 15th September 2013]

Norimatsu, T. and Horio, K., 2006. Wakamono zasshi ni okeru joyo kanji no katakana hyoki-ka – imibunseki no kantenkara [A study of“katakana” notation of“joyo-kanji”in young people’s magazines: from the perspective of semantic construal]. Journal of the Faculty of Humanities, the University of Kitakyushu,72,pp.19–32.

Okugakiuchi, K.,2010. Katakana hyokigo no iminitsuite no ichikosatsu: shintaisei to image no kantenkara [An analysis of meaning of words written in katakana – from the perspective of physical image]. Papers in Linguistic Science,16,pp.79–92.

Sanom M., 2008. Nihon-teki Keita iron [Analysing Japanese mobile phone]. Nikkei Trendy Net [Online].24 September. Available from: http://trendy.nikkeibp.co.jp/article/column/20080922/1018922/

Sekine, K., 2011. From Chernobyl to Fukushima: “Please do not go the way we did” Asahi Shimbun: Japan [Online]. 25 April. Available from: http://www.asahi.com/special/10005/TKY201104240184.html [Accessed on 16 January 2012]

Sperber, D. andWilson,D., 1995. Relevance: communication and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sperber, D. and Wilson, D., 2006. Pragmatics. In F. Jackson and M. Smith eds.,Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp.468-501

Sports Navi Plus, 2013. From judo to judo – gold medals in three consecutive days. Sports Navi Plus. [Online]

Available from http://www.plus-blog.sportsnavi.com/kagesupo143/article/291 [Accessed on 22nd October 2013]

Sugimoto, T.,2009. Nichieigo no heni sei – Eigo henshu no tsuzuriji hyoki to Nihongo katakana hyoki no hikaku bunseki [Variation in Japanese and English: a comparison between the orthography of English varieties and Japanese katakana notation]. SeijoBungei,9,pp.83–107.

Uchida, S., 2012. Discussion on irregular katakana uses. [email]

Wilson, D.,2004. Relevance theory and lexical pragmatics. UCL Working Papers in Linguistics,16, pp.343–360.

Wilson, D., Carston, R., 2006. Metaphor, relevance and the ’emergent property’ issue. Mind and Language, 21(3), pp.404-433

Wilson, D. and Carston, R., 2007. A unitary approach to lexical pragmatics: relevance, inference and ad hoc concepts. In: N. Burton-Roberts, ed.Pragmatics. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave.pp. 230–259.

Wilson, D. and Sperber, D.,2002. Relevance theory. UCL Working Papers in Linguistics,14, pp.249–287.

Wilson, D. and Wharton, T., 2006. Relevance and prosody. Journal of Pragmatics,38(10), pp.1559–1579.

Yamanashi, M., 2000. Ninchi gengogaku genri [Principles of cognitive linguistics]. Tokyo: Kuroshio.

Yomiuri Online, 2011. Differences between sexes that appear early. HatsugenKomachi. [Online] 25 February. Available from http://komachi.yomiuri.co.jp/t/2011/0225/389949.htm [Accessed on 22nd October 2013]

About the author

Dr. Ryoko Sasamoto is a lecturer in Japanese-Asian Studies in the School of Applied Language and Intercultural Studies, Dublin City University. She works within the framework of Sperber & Wilson’s Relevance Theory, with special interests in cognitive and affective user experience in multimodal communication and persuasive intentions.

There has been growing interest in research on disability sport internationally, yet little research has concentrated on the development of disability sport in China. This book focuses on elite disability sport in China in the context of history, politics, policies and practice from 1979 to 2012. It examines the relationship between athletes with disabilities and the three major disability games: the Paralympic Games, the Special Olympic Games and the Deaflympic Games. Three key questions are asked: What policies have ensured the success of elite disability sport? How do the elite sport system and management of elite disability sport work in China? In what way has elite disability sport empowered athletes with disabilities in China?

There has been growing interest in research on disability sport internationally, yet little research has concentrated on the development of disability sport in China. This book focuses on elite disability sport in China in the context of history, politics, policies and practice from 1979 to 2012. It examines the relationship between athletes with disabilities and the three major disability games: the Paralympic Games, the Special Olympic Games and the Deaflympic Games. Three key questions are asked: What policies have ensured the success of elite disability sport? How do the elite sport system and management of elite disability sport work in China? In what way has elite disability sport empowered athletes with disabilities in China?