Ills.: yangshuoshaolin.com

Abstract

Because of the long history and richness of civilization in China (Leung, 2008; Liu, 2009; Hu, Grove, and Zhuang, 2010), as well as the complexity and diversity of Chinese culture in mainland China and in the Chinese community worldwide (The Chinese Culture Connection, 1987; Fan, 2000), the task of designing an introductory course on Chinese culture for Westerners presents certain difficulties (Luk, 1991; Fan, 2000). While the content of a comprehensive course on Chinese culture remains to be decided, the present study explores a 12-week introductory course on four areas of Chinese culture. It was delivered to 16 Irish students who were doing a degree in Intercultural Studies. Each participant was asked to write a 500-word reflective journal entry every two weeks and an essay of 2,000–2,500 words at the end of the course.

The study aims to find out which area(s) and topic(s) might be of interest to or potential obstacles for Irish students in future participation in intercultural dialogue with Chinese people. Using the software Wordsmith Tools (Scott, 1996), the study identifies both the area and the sub-topic within each area that are of greatest interest yet previously unknown to Irish students.

The results show that the section on “love, sex, and marriage in China” was very well received and the most discussed topic in their journals and essays. The participants demonstrated fascination with the changing role of women in Chinese culture and identified shared ground in terms of marriage choices in both Irish and Chinese societies, which could help them to develop a deeper understanding of Chinese society and participate in intercultural dialogue from this perspective. A number of topics, such as martial arts films, the urban/rural divide, loss of face, etc., can be employed as prisms through which students can explore and understand elements of Chinese culture and its evolution over time.

The understanding of “face” in Chinese culture is perceived by the participants as being of great importance in intercultural and interpersonal communication, which could undoubtedly support engagement in open and respectful exchange or interaction between the Irish and Chinese. Interestingly, the participants indicated that it is difficult to understand that the use of linguistic politeness could lead to the speaker being perceived as “powerless” in Chinese society, which could mean that not being aware of this might lead to miscommunication between individuals with different cultural backgrounds. In general, the findings presented in this chapter may have significant pedagogical implications for teachers and students of intercultural communication, but may also be of interest to those with a practical involvement in intercultural dialogue. Introduction

Due to the complexity and diversity of Chinese culture in mainland China and in the Chinese community worldwide, in both the past and the present (The Chinese Culture Connection, 1987; Fan, 2000; Leung, 2008), it could prove difficult to define and establish the content of a course to introduce Chinese culture (Luk, 1991). Indeed, the selection of course content is also subject to the aims of the course and the needs of the target students. In the current study, the course “Introduction to Chinese Language and Culture” was designed to introduce four aspects of Chinese culture to any student in an Irish higher education institute who has not previously learned about or been exposed to Chinese culture. This article will first explore the content of this 12-week introductory course. I will then analyse the reflective journals and essays written by the participants in order to identify which area(s) of and topic(s) on Chinese culture might be of interest to or present difficulties for Irish students. Using statistically significant words and excerpts from the participants’ writing , this article investigates Irish students’ understanding of cultural differences between Chinese and Western societies, and how this understanding might influence their participation in intercultural dialogue with Chinese people in the future.

Course Design

The 12-week course was divided into four sections according to these four themes: (1) love, sex and marriage in China, (2) Chinese core values in martial arts, (3) Chinese social hierarchy and development, and (4) Chinese “face” and linguistic politeness. The content of the course also focused on reflecting traditional Chinese values, communist ideology, and Western influence on contemporary Chinese culture in the People’s Republic of China (Brick, 1991, p. 6; Fan, 2000). Core values of Chinese culture which are related to the four themes were also introduced in the course, because these values are likely to have remained stable in the development of Chinese history and can also be assumed to be shared by Chinese people in mainland China and worldwide (The Chinese Culture Connection, 1987; Fan, 2000).

The first theme, “love, sex and marriage in China”, consisted of an introduction to Confucianism and traditional Chinese values such as filial piety, benevolence, loyalty, and the observance of hierarchical relationships in the family (The Chinese Culture Connection, 1987; Fan, 2000). Several linguistic terms were also introduced to explore the key concepts in this area: huīyīn (marriage), xiăojiĕ (miss), qìzhì (disposition), and tóngzhì (comerade). In the second theme, “Chinese core values in martial arts”, a series of martial arts literature and films were selected in order to present cultural values (e.g. trustworthiness, humility, harmony with others, sense of righteousness/integrity) that are essential in Chinese society even nowadays.

It also introduced Chinese philosophical streams such as Buddhism and Taoism that are mentioned or embedded in Chinese martial arts. Chinese words such as wǔxiá (knight) and jiānghú (rivers and lakes) were also discussed in class in order to provide participants with an appreciation of the uniqueness of martial arts in Chinese culture. The third theme explored “Chinese social hierarchy and development”, concentrating on the shift away from the traditional Chinese hierarchy based on Confucianism and the social changes that have occurred in contemporary China, with a focus on the impact of communist ideology since the establishment of the P. R. China in 1949 and the influence of Western culture since the introduction of the open-door policy in 1978 (Leung, 2003).

This section of the course also examined core values such as benevolence, hard-work, solidarity, and patriotism, as well as the hierarchical ordering of relationships by status and the observance of this order in work situations. Concepts such as hùkŏu (household registration), dānwèi (work unit), and tiĕfànwăn (iron rice bowl) were employed to illustrate the development and changes in Chinese society. The fourth section of the course looked at “Chinese ‘face’ and linguistic politeness” in the past and in present-day China. Indigenous Chinese concepts such as “face” (miànzi; Leung, 2008) and guānxi (connection) were also investigated when examining the differences between Western and Chinese politeness.

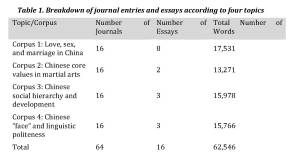

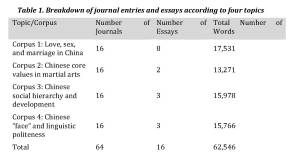

Table 1. Breakdown of journal entries and essays according to four topics

Data Collection

The data used for the current study consists of 64 reflective journal entries and 16 essays drawn from the assignments for the course. This course aimed at providing students with a basic knowledge of Chinese culture in such a way as to facilitate intercultural communication when they have contact with Chinese people in the future. A total of 16 Irish undergraduate students participated in the course, of whom 4 were male and 12 were female. The journals were written over a period of 12 weeks, with an average of 4 journal entries per student. Each student was asked to write a 2,000–2,500 word essay focusing on one topic that was of particular interest to him/her. Table 1 provides a breakdown of reflective journal entries and essays by topic.

The size of a corpus is a key factor in determining its representativeness (Atkins, Clear, and Osteler, 1992; Biber, 1993). Flowerdew (2004, p. 18) points out that a specialized corpus is indeed subject to both the needs and purposes of the research under investigation, as well as “pragmatic factors such as how easily the data can be obtained”, etc. Since the present study focuses on exploring Irish university students’ attitudes towards four aspects of Chinese culture, 64 reflective journal entries and 16 essays were collected and employed for the purposes of data analysis. The total number of words varies across the four topics, but on average ranged between 13,000 and 17,000 per topic. The four corpora consist of a total of 62,546 words, with an average length of 15,637 for each topic-specific corpus. All the journals and essays were saved in separate .txt files by topic of Chinese culture. The KeyWords function of Wordsmith Tools (Scott, 1996) was then employed to find the word frequency counts for each of the four topics. Through a comparison of each corpus with a reference corpus, any words that were statistically significant in the corpus were identified in order to establish common concerns and general attitudes towards each aspect of Chinese culture.

Results and Discussion

This research sets out to find quantitative information regarding attitudes towards four aspects of Chinese culture through corpus linguistic analysis and content analysis. Therefore, the results will be presented by topic.

Love, sex, and marriage in China

The five words which appear at the top of the KeyWords list in this category: marriage, Chinese, wedding, women, China. This reflects both the focus of the topic and the students’ interest on the role of Chinese women in marriage. The concordance tool (Concord) in WordSmith can be used to display these keywords in context. Concord shows that “marriage law” (N=25) came first in the list of most frequent clusters. Indeed, the Marriage Laws implemented in 1950 and 1980 have had a marked impact on Chinese society and have engendered a significant change in the role of Chinese women. This group of Irish students, which had a majority of females, showed genuine interest in this aspect of Chinese culture.

After the P. R. China was founded in 1949, the new government started to re-structure Chinese society and a series of marriage reforms, along with the enactment of the Marriage Law in 1950, were put in place in order to give equality to all Chinese citizens. These reforms aimed to, among other things, improve women’s rights by making their social status equal to that of men (Ettner, 2002, p. 44). The law provided greater freedom, especially for women, in the choice of mate and in terms of seeking a divorce (Pimentel, 2000; Ettner, 2002, p. 44; Leung, 2003). It also officially marked the end of the feudal marriage system which had existed in Chinese society for thousands of years (Engel, 1984; Pimentel, 2000; Leung, 2003). The 1980 Marriage Law further abolished any elements carried on from the feudal marriage system, i.e. prohibiting “mercenary marriage and bigamy” (Engel, 1984, p. 956). It also further consolidated the freedom of marriage by specifying that the foundation of a marriage is mutual affection (Engel, 1984, p. 956; Xia and Zhou, 2003, p. 237). At the same time, and for the first time in Chinese history, a no-fault divorce was allowed, i.e. “divorce should be granted with complete alienation of mutual affection” (Xia and Zhou, 2003, p. 237).

While the 1950 and 1980 Marriage Laws legislate for the equality of men and women to some extent, Chinese women have occupied an inferior social position within the male-dominated cultural hierarchy for thousands of years (Zhang, 2002, p. 79; Leung, 2003; Liu, 2004; Shi and Scharff, 2008). Therefore, there is still a long way to go in order to raise the status of women and achieve sexual equality in contemporary China, which can be reflected in attitudes towards fidelity and sex. According to a study conducted by Zha and Geng (1992, p. 13), most of the male and female respondents insisted that female fidelity is more important than male fidelity. Interestingly, more women than men said that they would tolerate their spouses having an extra-marital sexual relationship.

Participants in the current study also demonstrated their awareness regarding the role of women in Chinese culture: “Personally I think the tolerance of Chinese women to infidelity is fear of be [sic] left destitute if their husband leaves [. . .]” (Participant no.1) “[. . .] women have been devalued in Chinese society [and this] can be traced back to Confucianism, which is still highly valued and deeply rooted in Chinese history.” (Participant no. 7)

Even though a number of topics and some core values of Chinese culture were only briefly mentioned in class, the above comments show that the participants were able to see the connections between them. Furthermore, they even demonstrated an attempt to find the similarities between Chinese and Irish societies in terms of marriage choice: “. . . in the 70s and 80s, attitudes were much more conservative in Ireland. The dating culture was already prevalent, but parental approval would have been extremely important around this time. So already I can see a big similarity between Ireland and China.” (Participant no. 9)

Chinese core values in martial arts

The top five most frequently mentioned words in the participants’ writing are: martial, film(s), arts, Chinese, wushu. Although different representations of Chinese martial arts (e.g. a poem, historical records, fiction, etc.) were introduced in the course, the participants expressed particular interest in Chinese martial arts films, which seem to be what Chinese martial arts are most famous for. In spite of a long history of Chinese martial arts literature (Mok, 2001; Teo, 2009, p. 17), Western audiences tend to know martial arts through watching films, from the earlier movies starring Bruce Lee (word count N=24) and Jackie Chan (N=13) to the international success of “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” (N=30).

A variety of unique concepts are associated with Chinese martial arts, e.g. xia (xiá, knight), wushu (wǔshù, martial arts), and jianghu (jiānghú, as explained below), as well as a few core Chinese values, such as trustworthiness, humility, and sense of righteousness. It is inevitable that the meaning of “jianghu” (word count N=31) will be investigated when discussing Chinese martial arts. Jianghu, literally “rivers and lakes”, connotes a culturally specific imaginary world where martial arts are supposed to take place (Chan, 2001). It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to find an equivalent word in English due to the term’s richness of connotation. Five participants explicitly mentioned the helpfulness of watching films in understanding martial arts-related concepts.

One participant stated: “After watching the film my understanding of the concept of xia is much clearer [. . .] The other concept of jianghu can also be seen in the film. […] [I]t can be confirmed that the film ‘Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon’ is indeed a wuxia film thus the concepts of xia and jianghu can be identified in the film.” (Participant no. 15)

In general, films seem to be a useful and easily accessible way for Irish students to contextualize and visualize martial arts: “I think that after watching this martial arts film [‘Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon’] and researching the principle teachings of Confucianism, I now have a better understanding of the role that Confucianist [sic] beliefs have in Chinese society.” (Participant no. 8) “Also, what struck me, being somebody that has very little understanding of martial arts, the six scenes of battle [in the film] and where martial arts is being illustrated appeared to be more like a well-choreographed, exciting dance sequence than fighting.” (Participant no. 6) “I watched a recently released film entitled ‘Shaolin’ which I rented from a dvd store due to it being so recently released[.] Together with my friend from class we were able to share views and opinions on our understanding of how and why martial arts are used within the film.” (Participant no. 13)

The participants also identified a few topics that are relevant to and can be seen in martial arts cinema. For instance, Chinese philosophy (“Confucianism” word count N=22, “Buddhism” N=18, “Taoism” N=25) was discussed in some of the participants’ journals. Five participants examined how Chinese martial arts films depict gender differences, which connects with the first section of the course. The clear interest in Chinese cinema as a means to understand the culture suggests that film can be employed to impart a deeper understanding of a target culture (Bueno, 2009; Zhang, 2010). Foreign language films have previously been used in the classroom for the purposes of developing intercultural communication (King, 2002; Pegrum, Hartley, and Wechtler, 2005; Starkey, 2007; Pegrum, 2008). Despite the extensive use of cinema in the classroom to promote European languages and cultures (e.g. Garza, 1991; Secules, Herron, and Tomasello, 1992; Dupuy and Krashen, 1993; Chapple and Curtis, 2000; Pegrum, Hartley, and Wechtler, 2005; Zoreda, 2006), there is a scarcity of studies on using Chinese films to increase understanding of Chinese culture (Zhang, 2010). This is potentially an area that merits exploring for future research.

Chinese social hierarchy and development

Since both traditional and contemporary Chinese social hierarchies and development were introduced in the class, it is unsurprising to see the most frequent words in the participants’ writing were: society, urban, rural, Chinese, danwei. The indigenous concept of danwei (dānwèi, work unit) obviously attracts the attention of Irish students. It is generally the space of the socialist work unit (Bray, 2005, p. 1), specifically referring to any state-owned or state-operated factories in urban areas, public institutions, government departments, and military units (Solinger, 1995; Wang and Chai, 2009). It is defined as “an enclosed, multifunctional, and self-sufficient entity” and believed to be “the most basic collective unit in the Chinese political and social order” (Dittmer and Lu, 1996; Lu, 1997, p. 21). In terms of political order, danwei can be used as a mechanism to carry out governmental policies through the cadre corps working in the units. From the perspective of social organization, it provides a quasi-permanent membership entitling its members a variety of welfare supports, including housing, food, transportation, health care, etc. (Dittmer and Lu, 1996; Lu, 1997; Sartor, 2007, p. 48; Wang and Chai, 2009). For this reason, danwei means much more than a working place in Chinese society. Instead, it is even considered as an extension of the family which offers employment and material support for the majority of urban residents (Bray, 2005, p. 50; Sartor, 2007, p. 48). Therefore, the participants point out that this is a relatively “secure” (word count N=18) system.

However, the workplace is also perceived as representing a comparably “controlled” (N=19) and closed environment. Indeed, Bray (2005, pp. 34–35) has suggested that walled compounds have been used to define social space, e.g. danwei, and that rather than the enclosure or exclusion, the focus should be on “the spaces created by the wall and the forms of spatial and social practice which are inscribed within these spaces”. Interestingly, one participant realized the unique importance of danwei in Chinese society: “In conclusion it was fascinating to discover more about the [d]anwei. At the beginning, I did find it difficult to comprehend but having looked at some elements more closely I realise my initial perception was too rash and that a greater understanding was required to fully understand what it meant and how it impacts on society. It was very interesting for me to read some direct quotes to see just how content the workers seemed to be, but also to realise that America would try to recreate some aspects of the community spirits to which they attached a great value.” (Participant no. 3) The above quotation indicates that danwei is indeed a difficult concept for Westerners to understand. As Bray (2005, p. 3) has pointed out, there is no such an equivalent translation of this word and, consequently, the Romanized form of the word has been adopted in academic works. Nevertheless, it is possible for Westerners to acquire a better, if not full, understanding of this concept assisted by appropriate reading.

The economic reforms that have been introduced since the 1980s have brought fundamental changes to both danwei (Dittmer and Lu, 1996; Lee, 1999; Hassard et al., 2006; Wang and Chai, 2009) and the urban/rural divide, changes that have been observed by the participants. Rural and urban areas became officially divided in the P. R. China due to the rigid hukou (hùkoǔ, household registration, word count N=32) system. It is employed to control population movement by restricting all Chinese citizens to their birthplace for life (Bian, 2002; Sicular et al., 2007). There have been reforms of the hukou system which have concentrated on loosening the restriction of mobility while maintaining socio-political stability (Wang, 2004). The rapid development of the Chinese economy and the possibilities for labour mobility have led to a number of issues relating to migrant workers, and the participants demonstrated their awareness of these workers’ status in Chinese society, i.e. mingong (míngōng, peasant worker, word count N=48), who are usually people from rural areas that go to work in economically developed urban regions (Ngai, 2004; Chan and Ngai, 2009).

Chinese ‘face’ and linguistic politeness

Face, Chinese, loss, politeness, person: these were the five most frequent words in the KeyWords list for this corpus. The expression “loss of face” was ranked first in the list of frequent clusters in Concord (N=32), followed by “concept of face” (N=13). On the one hand, the result shows the participants’ awareness of the importance of “face” in Chinese culture (Cardon and Scott, 2003; Dong and Lee, 2007). On the other hand, it also indicates the potential difficulties in understanding “face” when participants invest their writing time to exploring the concept (Haugh and Hinze, 2003).

The “complex” (N=18) meaning of face was pointed out in some journal entries: “The concept of “[f]ace” or [m]ianzi is quite a complex concept to define and understand in terms of its meaning in Chinese society.” (Participant no. 16) “The concept of face in China is very complex.” (Participant no. 10) Although all the participants were majoring in Intercultural Studies rather than Business Studies, their understanding of face and loss of face is often exemplified in a “business” (N=29) context. This result seems to indicate the participants’ enthusiasm for applying the cultural information they acquire in the classroom. In fact, the high frequency of “person” in their writing reveals their tendency to provide examples to illustrate the concepts in context.

The participants were also interested in investigating the differences in the concept of face between the “West” (word count N=25) and China: “The concept of losing and giving face is extremely important in Chinese culture and differs greatly to the ideas of [W]estern culture.” (Participant no. 14) “The Chinese people are now aware of the way other business people from the [W]estern world operate, and because they deal with them often they are less likely to get loss [sic] face.” (Participant no. 15) “…it is first necessary to define ‘face’ in Chinese culture, as definitions differ between Western and Chinese cultures.” (Participant no. 3) Some participants demonstrated their awareness of the association between linguistic politeness and “power” (N=18) in Chinese society.

Interestingly, it seems difficult for them to understand the employment of linguistic politeness as an outward sign of being “powerless” in Chinese society: “I was really surprised to learn that in a social situation, the use of conventional polite terms would indicate inferiority. Especially when we learnt that in the context of a service encounter, such as in a shop, the customer should use polite language and the one working there should not, as they are in the position of power in the situation. This is the opposite of what happens in a service encounter in the Western world, where the motto ‘The customer is always right’ prevails, which means that the worker should do everything in their power to please the customer. Good manners are an essential part of this, proven by the fact that people would complain a lot if they were spoken to in an impolite manner in a shop or restaurant.” (Participant no. 8) “I found this topic [on power relations in terms of linguistic politeness] to be a very interesting one. It would no doubt be useful to know this if I ever go to China.” (Participant no. 2) The politeness theory proposed by Brown and Levinson (1987) indicates that power is one of the three factors that influence the choice of politeness strategies. Studies in Chinese contexts (Pan, 1995; Feng, Chang, and Holt, 2011) confirm that power is still a significant factor in determining politeness behaviours in Chinese communication. Indeed, China is a society with high awareness of hierarchy and power relations (The Chinese Culture Connection, 1987; Leung, 2008).

Traditionally, linguistic politeness, such as the self-denigrating and addressee-elevating language promoted in Confucianism, was usually employed by both the speaker and listener to show humility and mutual respect (Kadar, 2008; Pan and Kadar, 2011). Pan and Kadar (2011) explain that the traditional linguistic politeness has been lost due to a series of political changes in China since the end of the 19th century. The foreign invasion of China in the late 19th century brought with it advanced technology. It also raised doubts about traditional Chinese culture, including Confucianism, among Chinese intellectuals (Pan and Kadar, 2011, p. 1526). In addition, traditional polite expressions were further eliminated after the P. R. China was founded in 1949 and during the Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976 (ibid.). A large amount of linguistic politeness has been lost in the past few decades. In contemporary China, the employment of linguistic politeness is considered as signalling powerlessness in communication (Pan, 1995, 2000; Pan et al., 2006; Sun, 2008). This has been evidenced in the domain of customer service. A customer is usually a person who needs help from a service provider, which positions him/her as powerless in the social interaction and consequently polite expressions are used in order to receive the service. As exemplified in the statements above, it was shocking for the participants to find out the association between linguistic politeness and powerlessness in Chinese communication since it is significantly different from service encounter interactions in Western cultures (Merritt, 1976, 1984). Therefore, it is very likely that Irish students would experience cultural shock from this perspective in social interaction with the Chinese.

Conclusion

Through the analyses of the writings of a group of Irish students who had not previously learned about or been exposed to Chinese language or culture, the study identifies both the area and the sub-topic within each area that are of greatest interest to them. Of the four sections that were focused on in the course, the section on “love, sex and marriage in China” was very well-received and the most discussed in their journals and essays. “Throughout the course of this module, I have studied various aspects of Chinese culture. I have learned a lot from the classes and from the readings when completing the other reflective journals. I found the second lesson on ‘Love, Sexuality and Marriage in China’ [sic] the most interesting [. . .].” (Participant no. 2) “Throughout the course [. . .], I have discovered the different [m]arriage beliefs which are followed in China, and how they have changed over the years due to the Western influence one might say.” (Participant no. 4) The current study found that the Irish participants were fascinated with the changing role of women in Chinese culture.

To some extent, they explored the existence of shared ground in marriage choices in both Irish and Chinese societies, which could help them to develop a deeper understanding of this particular topic and participate in intercultural dialogue from this perspective. Interestingly, it seems difficult for Irish students to understand the association of linguistic politeness with powerlessness in Chinese society, which might lead to miscommunication between individuals with different cultural backgrounds. Despite the complexity and diversity of Chinese culture, the two quotations below show that the group of Irish students found the course a helpful and enjoyable way to explore and understand elements of Chinese culture: “I enjoyed [it] very much as it allowed me to understand a new way of living, a new idea, a new view of females in China, and Taiwan.

It allowed me to learn something new and discover new things.” (Participant no. 1) “I have now been studying ‘An Introduction to Chinese Culture and Language’. We have had some very interesting lectures, and class discussions.” (Participant no. 9) The present study might be at the forefront of Chinese cultural education, and the pedagogical implications for teachers and students of intercultural communication are potentially significant. However, the fact that culture is not static could present a substantial obstacle to designing a course to introduce Chinese culture to Western learners.

China is currently experiencing hyper economic growth, with an average 9% increase in GDP every year since 1978 (Kuijs and Wang, 2006; Yuan and Liu 2009, p. 17). It is inevitable that a culture will continue to evolve and that people in this society will change their values and practices. In the current study, a number of core cultural values that have been researched and confirmed in Chinese society were introduced to the students.

In addition, a few indigenous concepts were employed in order to guide the Irish students through the historical changes in Chinese culture and society. The course also had to focus both on the mainland China and on Chinese culture as a whole. The dangers of over-generalization and ignorance of regional diversity are very real. It might be worthwhile for future research to explore pedagogical methods of teaching cultural differences within China and amongst Chinese communities worldwide.

REFERENCES

Atkins, S., Clear, J. and Osteler, N., 1992. Corpus design criteria. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 7(1), pp. 1–16.

Bian, Y., 2002. Chinese social stratification and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, pp. 91–116.

Biber, D., 1993. Representativeness in corpus design. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 8(4), pp. 243–257.

Bray, D., 2005. Social space and governance in urban China: the danwei system from origins to reform. Stanford: Standard University Press.

Brick, J., 1991. China: a handbook in intercultural communication. Sydney: Macquarie University.

Brown, P. and Levinson, S., 1987. Politeness: some universals in language use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bueno, K., 2009. Got film? Is it a readily accessible window to the target language and culture for your students? Foreign Language Annals, 42(2), pp. 318–338.

Cardon, P. W. and Scott, J. C., 2003. Chinese business face: communication behaviors and teaching approaches. Business Communication Quarterly, 66(4), pp. 9–22.

Chan, C. K. and Ngai, P., 2009. The making of a new working class? A study of collective actions of migrant workers in south China.

The China Quarterly, 198, pp. 287–303. Chan, S. C., 2001. Figures of hope and the filmic imaginary of jianghu in contemporary Hong Kong cinema.

Cultural Studies, 15(3/4), pp. 486–514.

Chapple, L. and Curtis, A., 2000. Content-based instruction in Hong Kong: student responses to film. System, 28, pp. 419–433.

Dittmer, L. and Lu, X., 1996. Personal politics in the Chinese Danwei under reform. Asian Survey, 36(3), pp. 246–267.

Dong, Q. and Lee, Y., 2007. The Chinese concept of face: a perspective for business communicators. In: Decision Sciences Institute (Southwest Region) Conference Proceedings. San Diego, USA, 13–17 March. pp. 401–408.

Dupuy, B. & Krashen, S. D., 1993. Incidental vocabulary acquisition in French as a foreign language. Applied Language Learning, 4, pp. 55–63.

Engel, J. W., 1984. Marriage in the People’s Republic of China: analysis of a new law. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 46(4), pp. 955–961.

Ettner, C., 2002. In Chinese, men and women are equal – or – women and men are equal? In: M. Hellinger and H. Bubmann, eds. Gender across languages: the linguistic representation of women and men, volume II. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 29–56.

Fan, Y., 2000. A classification of Chinese culture. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 7(2), pp. 3–10.

Feng, H., Chang, H., and Holt, R., 2011. Examing Chinese gift-giving behavior from the politeness theory perspective. Asian Journal of Communication, 21(3), pp. 301–317.

Flowerdew, L., 1998. Corpus linguistic techniques applied to textlinguistics. System, 26(4), pp. 541–552.

Flowerdew, L., 2004. The argument for using English specialized corpora to understand academic and professional language. In: U. Connor and T. Upton, eds. Discourse in the professions: perspectives from corpus linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp.11–36.

Garza, T. J., 1991. Evaluating the use of captioned video materials in advanced foreign language learning. Foreign Language Annuals, 24(3), pp. 239–258.

Hassard, J., Morris, J., Sheehan, J., and Xiao, Y., 2006. Downsizing the danwei: Chinese state-enterprise reform and the surplus labour question. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(8), pp. 1441–1455.

Haugh, M. and Hinze, C., 2003. A metalinguistic approach to deconstructing the concepts of “face” and “politeness” in Chinese, English and Japanese. Journal of Pragmatics, 35, pp. 1581–1611.

Hu, W., Grove, C. N., and Zhuang, E., 2010. Encountering the Chinese: a modern country, an ancient culture. Boston: Nocholas Brealey Publishing.

Kadar, D. Z., 2008. Power and formulaic (im)politeness in traditional Chinese criminal investigation. In: H. Sun & D. Z. Kadar, eds. It’s the dragon’s turn – Chinese institutional discourses. Bern: Peter Lang. pp.127–180. King, J., 2002. Using DVD feature films in the EFL classroom. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 15(5), pp. 509–523.

Kuijs, L. and Wang, T., 2006. China’s pattern of growth: moving to sustainability and reducing inequality. China & World Economy, 14, pp. 1–14.

Leung, A. S. M., 2003. Feminism in transition: Chinese culture, ideology and the development of the women’s movement in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20, pp. 359–374.

Leung, K., 2008. Chinese culture, modernization, and international business. International Business Review, 17, pp. 184–187.

Liu, J., 2004. Holding up the sky? Reflections on marriage in contemporary China. Feminism & Psychology, 14, pp. 195–202.

Liu, Y., 2009. Learning and teaching Chinese language and culture in Dublin: attitudes and expectations. Unpublished thesis (M.Phil.), School of Languages, Dublin Institute of Technology.

Lu, X., 1997. Minor public economy: the revolutionary origins of the danwei. In: X. Lu and E. J. Perry, eds. Danwei: the changing Chinese workplace in historical and comparative perspective. New York: M. E. Sharpe, Inc. pp. 21–41.

Luk, B. H., 1991. Chinese culture in the Hong Kong curriculum: heritage and colonialism. Comparative Education Review, 35 (4), pp. 650–668.

Merritt, M., 1976. On questions following questions in service encounters. Language in Society, 5, pp. 315–357.

Merritt, M., 1984. On the use of “okay” in service encounters. In: J. Baugh and J. Sherzer, eds. Language in use. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. pp. 139–147.

Mok, O., 2001. Strategies of translating martial arts fiction. Babel, 47(1), pp. 1–9.

Ngai, P., 2004. Women workers and precarious employment in Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, China. Gender and Development, 12(2), pp. 29–36.

Pan, Y., 1995. Power behind linguistic behavior: analysis of politeness phenomena in Chinese official settings. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 14, pp. 462–481.

Pan, Y., 2000. Facework in Chinese service encounters. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 10, pp. 25–61.

Pan, Y., Hinsdale, M., Park, H., and Schoua-Glusberg, A., 2006. Cognitive testing of translations of ACS CAPI materials in multiple languages. [online]. Available at: <http://www.census.gov/srd/papers/pdf/rsm2008-06.pdf > [Accessed on 12 February 2013].

Pan, Y. and Kadar, D. Z., 2011. Historical vs. contemporary Chinese linguistic politeness. Journal of Pragmatics, 43, pp. 1525–1539.

Pegrum, M., 2008. Film, culture and identity: critical intercultural literacies for the language classroom. Language and Intercultural Communication, 8(2), pp. 136–154.

Pegrum, M., Hartley, L., and Wechtler, V., 2005. Contemporary cinema in language learning: from linguistic input to intercultural insight. Language Learning Journal, 32, pp.55–62.

Pimentel, E. E., 2000. Just how do I love thee?: marital relations in urban China. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, pp. 32–47.

Sartor, V., 2007. Danwei or my way? Beijing Review, 5 July, pp. 48. Scollon, R. and Scollon, S. W., 1995. Intercultural communication: a discourse approach. London: Blackwell. Scott, M., 1996. Wordsmith Tools. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Secules, T., Herron, C., and Tomasello, M., 1992. The effect of video context on foreign language learning. The Modern Language Journal, 76(4), pp. 480–490.

Shi, Q. and Scharff, J. S., 2008. Social change, intercultural conflict, and marital dynamics in a Chinese marriage in brief concurrent individual and couple therapy. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 5(4), pp. 302–321.

Sicular, T., Yue, X., Gustafsson, B., and Shi, L., 2007. The urban-rural income gap and inequality in China. Review of Income and Wealth, 53(1), pp. 93–126.

Solinger, D. J., 1995. The Chinese work unit and transient labor in the transition from socialism. Modern China, 21(2), pp. 155–183.

Starkey, H., 2007. Language education, identities and citizenship: developing cosmopolitan perspectives. Language and Intercultural Communication, 7(1), pp. 56–71.

Sun, H., 2008. Participant roles and discursive actions: Chinese transactional telephone interactions. In: H. Sun and D. Z. Kadar, eds. It’s the dragon’s turn – Chinese institutional discourses. Bern: Peter Lang. pp.77–126. Teo, S., 2009. Chinese martial arts cinema: the wuxia tradition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. The Chinese Culture Connection, 1987. Chinese values and the search for culture-free dimensions of culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 18(2), pp. 143–164.

Wang, F., 2004. Reformed migration control and new targeted people: China’s hukou system in the 2000s. The Chinese Quarterly, 177, pp. 115–132.

Wang, D. and Chai, Y., 2009. The jobs-housing relationship and commuting in Beijing, China: the legacy of danwei. Journal of Transport Geography, 17, pp. 30–38.

Xia, Y. R. and Zhou, Z. G., 2003. The transition of courtship, mate selection, and marriage in China. In: R. R. Hamon and B. B. Ingoldsby, eds. Mate selection across cultures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, pp. 231–246.

Yuan, F. and Liu, M., 2009. Anatomy of the Chinese business mind: an insider’s perspective. Singapore: Cengage Learning Asia Pte Ltd.

Zha, B. and Geng, W., 1992. Sexuality in urban China. The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, 28, pp. 1–20.

Zhang, D. and Slaughter-Defoe, D. T., 2009. Language attitudes and heritage language maintenance among Chinese immigrant families in the USA. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 22 (2), pp. 77–93.

Zhang, H., 2002. Reality and representation: social control and gender relations in Mandarin Chinese proverbs. In: M. Hellinger and H. Bubmann, eds. Gender across languages: the linguistic representation of women and men, Volume II. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, pp.73–80.

Zhang, Q., 2010. Students’ attitudes towards Chinese and their development of intercultural sensitivity. In: Columbia University, First Teachers College, Columbia University Roundtable in Second Language Studies (TCCRISLS). New York, USA, 29 September–2 October.

Zhang, Y., 2004. Chinese national cinema. London: Routledge. Zhuo, J., 2010. From positivity to possibility, propriety and necessity: semantic change in culture. Journal of Chinese Language and Discourse, 1(1), pp. 66–92.

Zoreda, M. L., 2006. Intercultural moments in teaching English through film. Reencuentro, 47, pp. 65–71.

Published in: Fan Hong, Peter Herrmann & Daniele Massccesi (Eds.) – Contructing the ‘Other’ – Studies on Asian Issues – Europaeischer Hochschulverlag, Bremen. ISBN 978 3 86741 892 8

“既有东方的气质和教育,也有西方的教育和背景。这也是一种优势吧。”

“既有东方的气质和教育,也有西方的教育和背景。这也是一种优势吧。”