Chapter 5: Irish FDI In China ~ Evidence, Potential And Policy ~ Irish Investment In China. Setting New Patterns

Introduction

Introduction

Having set out the locational advantages and disadvantages which China possesses, this chapter will explore the non-applicability of Irish FDI in China to Barry et al‘s (2003) model for developed economies, and will attempt to explain why there is such a divergence. It can be argued that there is a view which equates outward FDI with the re-location of jobs abroad. In order to address this perception, the effects of outward FDI on the home economy will be explored. Acknowledging that our sub-hypothesis holds and that the investment climate in China is different from that faced by Irish investors in developed economies, we will explore our prescriptive research question, namely the role which exists for government in supporting potential investors who wish to enter the Chinese market.

Barry’s Model

Barry et al’s (2003) model states that Irish outward FDI is disproportionately horizontal in nature and oriented towards non-traded sectors. This model is based on an analysis of Irish FDI in the traditional destinations for Irish FDI, namely the US and UK, both of which are developed economies. This research analysed Irish FDI in China, a developing economy. While accepting the limited nature of this research, it was found that 82% of FDI is in the traded sector and only 18% in the non-traded sector. It can be said, therefore, that this finding is at variance with the model for developed economies, as set out by Barry et al (2003). Secondly, in relation to the horizontal or vertical nature of Irish FDI in China, this research identified 55% as being of a horizontal nature and 45% as being vertical. Barry et al’s model states that Irish traditional FDI in developed economies is “disproportionately horizontal in nature’. 55% could not be described as ‘disproportionately horizontal’. Accordingly, this finding also deviates from Barry et al’s model. Accepting the difficulty of measuring the true level of horizontal versus vertical FDI, as highlighted in the literature review, the figure of 55% is below the level of 70% which Moosa (2002) contends may be the general order of horizontal FDI. This points to the level of horizontal Irish FDI in China being somewhat lower than the norm and not as strong as would have been anticipated had it been in accordance with Barry et al’s model.

We can say that this research indicates that the current wave of Irish FDI in China is predominately in the traded sector and marginally horizontal in nature.

Accepting that the sample size for this research is limited, it is nevertheless an accurate reflection of current investment patterns by Irish MNEs in China.

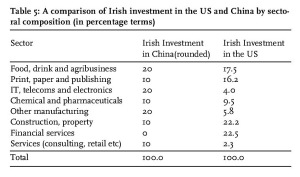

Table 5: A comparison of Irish investment in the US and China by sectoral composition (in percentage terms)

Irish FDI in China and Barry’s Model

It is also interesting to examine whether the limited Irish investment in China diverges or conforms to the sectoral composition identified by Barry et al (2003) for developed economies. Using the categorisation of Irish investment in the US put forward by Barry et al (see table 3 in previous chapter), the following comparisons can be made (Table 5):

The percentage for food, print and chemicals is not greatly different between both categories. IT, telecoms and electronics are considerably more important in the case of China. Significant deviations can be identified in ‘other manufacturing’, financial services and construction to a lesser degree. Notably, the Irish financial service sector is absent from China. Again acknowledging the small sample size of this research, current Irish investment trends into China show a divergence from patterns identified for investment in the US.

Why then does Irish FDI deviate from Barry et al’s model and also diverge in sectoral composition from that identified in traditional destinations for Irish outward FDI? There may be several possible explanations.

Recalling that firms invest abroad because they possess ownership and internalisation advantages, Barry et al (2003) suggest that R&D and superior product differentiation through advertising are generally found to be the most important firm-specific assets associated with multinationality; but Irish MNEs do not appear to follow the standard pattern associated with multinationality. Instead, they propose that the predominant proprietary assets which Irish firms possess are in the fields of management and expertise, mainly in non-traded sectors. However, this research found that the composition of Irish MNEs investing in China is largely in the traded sector. It is possible, therefore, that because the expertise of Irish MNEs largely lies in the non-traded sector, this is inhibiting current levels of FDI in China, given the largely manufacturing and traded nature of the Chinese economy at this point in time.

Secondly, the structure of the Irish economy can be broadly defined as highvalue output with little high-volume low-value manufacturing. (This results from the relatively high cost structure of the economy, as compared with developing economies). While Barry et al point out that the Investment Development Path hypothesis is silent on the distinction between vertical and horizontal FDI, they claim that as production costs rise there is an incentive for domestic firms to engage in vertical FDI, moving labour-intensive components to countries with a locational advantage in low-cost labour. This opportunity was identified by a very limited number of Irish MNEs. While China’s low wage cost environment may facilitate some Irish investment, market opportunity remains the primary investment objective.

Barry et al point to a large increase in outward investment by Irish firms in the US in hi-tech sectors such as information technology and the pharmaceutical industries. There has been limited investment by the Irish information technology industry in China and none by the pharmaceutical industry. IPR is a substantial component of ownership advantage in both of these industries. This research identified the risk to intellectual property rights (IPR) which investing in China may pose. This view was reflected not only among Irish MNEs which have invested in China, but also among executives of Irish MNEs which have invested in Eastern Europe. The threat to IPR was identified by the latter category as the most significant reason not to invest in China. The absence of predictable contract law was also cited. This was also evidenced by Irish investors in China in the food and chemical industries in China. Therefore, the information technology and the pharmaceutical industries may not be willing to commit to China until they are assured that their primary ownership advantage, namely IPR, will be adequately protected.

A factor possibly underlying the high level of investment in traded sectors may be the rapid emergence of China’s consumer base. In the case of China, the development of a critical mass of high-spending consumers has occurred in a relatively short period of time. It is possible that indigenous firms have not developed adequately to respond to the demands of consumers. However, with the focus in Irish industry on the service sector, Irish firms may not be well placed to take advantage of current consumer trends in China. A fifth possible explanation is that China’s service sector is in the early stages of development, whereas this represents a strong component of Irish industry. Therefore an explanation for the divergence in Irish investment in China from that identified by Barry et al for developed economies could be that it is the Irish manufacturing sector which is predominately investing in China, as against in developed economies.

The reasons advanced for the divergence between the results of this research and that of Barry et al (2003) point to the under-developed service sector, the lack of respect for legal norms, and the large manufacturing component in the Chinese economy. Du Pont (2000) has identified the emergence of the service and construction sectors. This may present additional locational advantages for Irish investors. By analysing industries in which Irish MNEs possess ownership and internalisation advantages it would be possible to identify which sectors may be keen to exploit China’s locational advantage in the coming years.

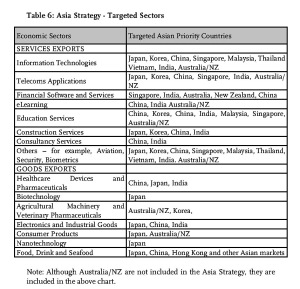

Table 6: Asia Strategy – Targeted Sectors

Note: Although Australia/NZ are not included in the Asia Strategy, they are included in the above chart. Source: Government of Ireland (2005)

The Potential for Irish Investment

The Government of Ireland’s (2005) Asia Strategy provides assistance is seeking to identify which sectors of the Irish economy are likely to possess the ownership and internalisation advantages required to exploit China’s locational advantages and overcome potential locational disadvantages. While the focus of the Asia Strategy is trade, it can be argued that these sectors are also likely to succeed in the investment domain, given the strong relationship between trade and investment. Table 6 sets out the Government’s recommendation as to which sectors of the economy should intensify their efforts in particular Asian economies.

The major sectors highlighted for the Chinese market in the goods sectors are healthcare devices, electronics, and food, drink and seafood. In the services sector, the categories are information technology, telecoms, financial software, education, and construction. Of these, Irish MNEs have already invested in the electronics, food, information technology and construction categories. In the case of the four remaining sectors, non-Irish MNEs were included in this research so as to capture the experience and perceptions of executives from all eight industrial sectors which are suggested as target sectors for developing economic links with China. The following section will consider issues of note raised by the executives from these industries and potential areas for investment will be highlighted. However, an in-depth analysis of the sectoral opportunities for investors lies outside the scope of this research.

Within the goods sector, the need to strengthen IPR protection was identified as a locational challenge by the executives from the electronics and food sectors. The food MNEs which have invested in China have decided to participate in the business-to-business sector and not the retail sector. They identified this as a stronger means of protecting intellectual property and also recognised the high cost of entry barriers to the retail market in terms of advertising costs. One food sector executive also spoke of the MNE’s plan to service the market in the west coast of the US from its Chinese plant rather than from Europe, which is what it does at present. This locational advantage for European investors was not highlighted in the literature on European investment in China. A food sector executive also spoke of the lack of national treatment. The electronics executive identified the critical mass of electronic MNEs in China as a key consideration in deciding to invest.

Barry et al (2003) point to the increase in the number of Irish IT MNEs investing abroad since 2000. This research identified a divergence of views between the executives of the Irish and the non-Irish IT MNEs, with the former citing IPR risk as being at the same level as in other markets, whereas the latter spoke of the significant risk which IPR violation poses. An executive of an Irish IT MNE which has invested in Eastern Europe cited the potential risk to IPR as a reason for not investing in China. McDonnell (1992) argues that if a sufficient return accrues to the parent firm to compensate for this risk, then the location of R&D overseas is deemed worthwhile. It would appear that if a firm is manufacturing retail software in China, there is a potential risk of IPR violation. This risk is reduced when the MNE operates in the business-to-business sector exclusively.

There is currently no Irish investment in the telecoms sector in China. There is a high level of state control in the telecommunications industry. ‘As the reform of state-owned telecoms continue, the market is not creating opportunity for foreign actors as understood under China’s WTO commitments’. (European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, 2005: 223) The fixed line and mobile network is state owned and there is scope for investors in the telecoms equipment sector only. No particular locational disadvantages were identified in this sub-sector.

The financial sector was identified as one of strong regulation, but also one of opportunity. China’s growth over the past 25 years has been achieved within the context of a closed banking system. This worked by channeling individual savings into state-owned banks which were used to fund state-owned enterprises. With the opening up of the banking sector in 2006 in response to WTO obligations opportunities will increase for foreign banks to offer loans to profitable private and state-owned enterprises. This presents an opportunity for niche market lending. It also offers significant financial service opportunities as the state-owned ‘big four’ banks will be obliged to restructure and modernise. The banking executive identified a skills deficiency in Chinese banks. This represents a locational challenge for foreign investors who wish to establish banking operations in China, but a market opportunity for providers of specialised financial services.

The education sector in China is closely regulated, as identified by an executive from this sector. If Irish investors wish to enter this sector, it would seem that the optimal route is to co-invest with a Chinese minority shareholder. Because of the risks which joint ventures pose to ownership advantage, as identified in this research, this structure is best avoided. It is also important that education providers appreciate the changing structure of the Chinese market. ‘China graduated a million technicians and engineers in 2001. That figure leapt to 2 million in 2003 and will go still higher. And the quality of engineering training has improved to the extent that fewer Chinese are now going to the United States for engineering degrees because they can obtain excellent education more cheaply at home’. (Lieberthal and Lieberthal, 2004: 4-5) This trend points to fewer Chinese students being willing to make the investment associated with studying abroad. If this trend continues, education providers from developed economies need to re-focus their efforts and seek to create strategic partnerships with Chinese colleges and, in addition, to consider the direct provision of education services in China, rather than seeking to attract Chinese students to study abroad exclusively. An option which several Irish third-level institutions have successfully established is one whereby students study in both the Chinese and Irish institutions e.g three years study in China and one in Ireland.

As identified by Barry et al (2003), the construction sector is one of the most active in Irish outward FDI. Xianming (2004) gives an indication of the size of this sector in China. 200 million metric tons of cement are produced every year in Western Europe. In China the figure is 1,000 million metric tons. Irish construction multinationals have already displayed their ownership and internalisation advantages and have an overseas presence. China would seem to be the appropriate next stage of investment, given the nature of the expanding industry in China and the locational advantage which this confers.

In addition to these sectors, some Irish firms may wish to examine the opportunities for moving low-value manufacturing to China and strengthening their head-office operations at home. This could have the outcome of placing the firm on a stronger financial footing in the medium term. The reality is that it is becoming increasingly difficult for Irish companies to profitably manufacture lowvalue products in Ireland, given the relatively high cost base as compared with Asia. If a firm wishes to protect its ownership advantage, it may have to evaluate its internalisation advantage and examine the option of creating a manufacturing subsidiary in China whilst retaining the higher-paid jobs in the home economy e.g. finance, design etc. This practice is sometimes portrayed as the relocation of jobs, but the reality is that it is difficult to continue such manufacturing in developed economies. In the medium term, the result is the retention of higher paid and more skilled jobs in the home economy.

Home Country Effect

‘People take national pride when their MNEs do well in Fortunes’ ranking of the largest firms in the world, but they worry when they see their companies closing domestic plants and opening up new ones in cheap-labour countries. Feelings are mixed because the issue is intricate’. (Navaretti and Venables,2004: 217) Responding to this argument, O’ Toole (2007: 397) argues that ‘the small number of studies that examine the productivity effects of offshoring production at an aggregate economy wide level suggest that it has a positive impact in the long run, particularly for small countries like Ireland’. In the same vein, Forfás (2001) argues that outward FDI should not be seen as an indication of economic decline, but a restructuring into higher value-added activities that will form the basis of long-term growth in competitiveness, exports and employment.

While by no means conclusive, overseas studies suggest that outward direct investment has been broadly beneficial for the ‘home’ economies concerned, boosting domestic exports, employment and wages, and providing a catalyst for restructuring of the domestic economy into higher value-added activities… Where key drivers in the business environment, such as taxation, infrastructure and the availability of skilled workers are supportive of high value-added activities being located in the domestic economy, then outward direct investment acts as a positive force in economic development, leading to the creation of high-skilled, highly paid employment. (Forfás 2001: Foreword)

Outward FDI is seen as having effects primarily in the areas of employment, taxation, and technology transfer. There is still considerable debate among economists about the employment effects of FDI in both the host and the home economies. In particular, the effect of outward FDI on employment levels at home is a controversial issue. (Moosa, 2002) Critics argue that outward FDI diminishes employment levels at home as the output of foreign subsidiaries becomes a substitute for output from the parent firm in the home economy. However, proponents of outward FDI contend that FDI creates jobs in the domestic economy because domestic firms export more when they have foreign subsidiaries.

Blomstrom et al (1988) analysed the employment data of Swedish MNEs, which showed that MNEs with subsidiaries abroad have higher levels of employment in head office operations when compared with firms which have not invested abroad. Head and Ries (2001) conducted research on 932 Japanese manufacturing firms over a 25-year period. They confirmed a complementarity between FDI and employment. The relationship, however, varies across firms. They found substitution when firms are not vertically integrated and assembly facilities in foreign countries are not supplied by intermediates produced at home.

Forfás (2001) clearly does not subscribe to the notion that outward FDI is a relocation of Irish jobs that will damage Irish industry.

Despite fears that outward direct investment by Irish companies may lead to a ‘hollowing out’ of industry and loss of exports, studies of countries with long experiences of high levels of outward direct investment all indicate that outward direct investment and exports are broadly complementary. According to one OECD study of member countries, each $1 of outward direct investment was associated with $2 of additional exports and a trade surplus of $ 1.70. (Forfás, 2001: 4-5)

Forfás also points to the international evidence which suggests that outward FDI has broadly positive effects on employment and wage levels in the domestic economy. Research commissioned by Forfás shows that ‘overseas investment by Irish companies has created demand for high-skilled employment at their respective head offices in Ireland e.g. for accountants, managers and marketing specialists’. (Forfás, 2001: 5)

In support of this view, the executive of an Irish MNE specifically argued that the company’s investment in China has added value to global operations and not threatened jobs at the Irish parent firm. Indeed, it was argued that having an R&D facility in China has helped the firm acquire new clients in China and grow global operations. The literature on the effect of outward FDI on employment in the home economy is far from conclusive. There appears to be some evidence that vertical FDI may complement domestic activities, whereas horizontal FDI may have a substitution effect. ‘These results contrast with the general belief that investments in cheap-labour countries weaken home activities, whereas those in other advanced economies enhance the national presence in foreign markets.

The reason is probably that vertical investment reduces production costs for the MNE as a whole, therefore raising output and employment of complementary activities at home or at least preventing them from declining’. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 44) This research established that Irish FDI in China does not follow the general trend identified by Barry et al and is not predominately horizontal. If vertical FDI is complementary to employment in a home economy, then Irish FDI in China may have less of an impact on employment in Ireland than outward FDI to other locations where horizontal FDI dominates.

Even if commentators hold differing views on this issue, there is a public perception that outward FDI involves the relocation of jobs to a third country. Perhaps this is an issue which needs to be addressed by commentators. While it may not be the most popular issue to address, the Irish economy is in a state of transition, having recently become a net exporter of FDI. From an economic governance perspective, it is important that issues surrounding this development are explored and policies enunciated.

Outward FDI also has an effect on taxation. Feldstein (1994) considers the effect of outward FDI in both the host and the home economies on taxes and tax credits. He argues that in the event of outward FDI the national income of the home economy will be affected, depending on the magnitude of the loss of tax revenue to the host economy and the use of foreign debt. He analyses these two factors, assuming most national savings remain in the home economy. He points out that the payment of tax to the host government by a subsidiary of the investing firm represents a loss of revenue by the home government. If investing firms receive tax credits for these payments, as they would do if a double taxation treaty exists, the firm will be indifferent to where the tax is paid. The firm will remain indifferent until the after-tax rate of return on the foreign investment is equal to the after-tax return on domestic investment. Another pertinent issue is whether or not outward FDI has an impact on technology up-grading and investment in R&D in the home economy.

Technology transfer to the host economy can take place through the adoption of foreign technology and the acquisition of human capital. FDI by MNEs is considered to be a major channel for the transfer of technology to developing economies. (Moosa, 2002) However, multinational enterprises will invest in technological research or the adaptation of their technology or in up-skilling local labour only to the extent that such investment holds a clear prospect of profit. The gains which accrue to the host economy are largely incidental, arising from the fact that it is in the multinational’s interest for such transfers to take place (McDonnell, 1992). Moosa (2002) argues that the benefits of technology’s accruing to the investing firm and the host economy are substantial.

From the perspective of the home economy as a whole, rather than the individual firm, there is an interest in retaining the key technological components at home. What may be of value to the home economy is exporting slightly obsolete technology to the host economy, which can be used to increase market penetration.[i] In order to maximise long-term growth, technologically advanced countries need to protect high-value technology. However, the individual firm is a profit-maximiser and will be indifferent as to where it locates its intellectual property as long as the ownership advantage can be adequately protected.

While there will be understandable adverse comment on individual factory closures in developed economies when manufacturing facilities are relocated to lower-cost economies, the evidence would appear to indicate more positive than negative effects. ‘Foreign investments are more likely to strengthen than to deplete home activities… Comparing firms investing abroad and national firms just operating in the home country, we find that investing abroad enhances the productivity path of investing firms’. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 239)

Acknowledging that research on home country effects is limited, the material available indicates that it is in the long-term interests of the home economy for its firms to invest abroad because of the potential for market expansion or the production of goods at a lower cost. In the case of Ireland, a detailed econometric model would be required to accurately predict the likely outcome. One of the problems identified by Moosa (2002) is the lack of data to adequately assess the impact of outward investment on employment.

Irish Public Policy

The sub-hypothesis under study has been found to be valid, as this research has indicated that the business environment in China is relatively different from that experienced by Irish investors in traditional destinations for Irish outward FDI. Given this challenging environment and the presence of imperfect market conditions, the question arises as to the role which exists for state intervention in ameliorating these market imperfections.

There is no enunciated government policy on outward FDI. While there are understandable emotive connotations associated with outward FDI, in today’s globalised economy national governments evaluate their economic strategies and policies on an on-going basis. With Ireland now a net exporter of FDI, perhaps it is opportune for a policy debate on this economic governance issue.

Ireland is an extremely open economy and subject to external economic pressures. The degree of transnationality of host countries, as measured by UNCTAD’s Transnationality Index,[ii] shows that the most transnationalised economy in 2003 was Hong Kong, which was followed by Ireland in second place. (UNCTAD, 2006) In addition, Forfás and Enterprise Ireland (2004) point out that companies supported by Enterprise Ireland supported over 23,000 workers in overseas operations in 2003. This figure is equal to 17.5% of total employment in these companies. Given the positive effects of outward FDI, particularly in strengthening high-value wage employment at the head office, such developments have policy implications and require consideration.

Table 7: FDI Promotion Programmes of Industrialised Countries

Source: International Finance Corporation (1997: 23)

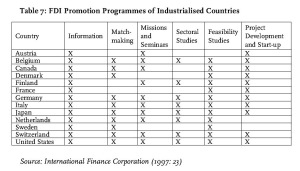

Indeed, governments in a number of other developed economies accept that market imperfections exist in the case of outward FDI, and operate investment promotion programmes to help national firms that wish to invest abroad. These programmes are generally focused on the provision of information on the target country, sponsoring missions of potential investors, matching potential investors to projects, and giving financial support for feasibility studies. Small- and medium-sized enterprises are normally targeted on the assumption that they lack the resources to seek out investment opportunities. The International Finance Corporation (1997: 23) argues that ‘the use of public funds is justified by a market imperfection, in this case the cost and difficulty of securing information about investments in developing countries’. Table 7 sets out the range of services available to potential outward investors in 13 developed economies.

In an interview with a senior executive of Enterprise Ireland it was confirmed that assistance may be provided to outward investors if it could be shown that outward FDI would not adversely affect employment in the Irish firm’s operation and would add value to the Irish firm. Assistance in gathering information would be offered on this basis. Also, it would be possible to include such companies in trade missions, but not to provide a specific investment focus. Perhaps consideration could be given to formalising such arrangements. Understandably, government agencies must operate within very careful parameters and not be seen to assist any company relocating and shedding jobs in the home economy, but they do work with companies who need to outsource certain activities which will make the company’s overall position more secure and help make it more competitive at home.

Currently no individual state agency has responsibility for outward FDI in the manner in which Enterprise Ireland is charged with promoting Irish trade and the Industrial Development Agency is responsible for attracting inward FDI in Ireland. Understandably, facilitating Irish outward FDI is a sensitive issue but, as argued above, such FDI should be developed if Ireland is to further develop its economy.

This research identified market imperfections in the Chinese economy, which investors must deal with. Economic theory makes provision for state intervention when market imperfections exist. (Mulreany, 1999) Drawing on the findings of this research, potential areas of state support could be explored with a view to ameliorating the impact of China’s market imperfections. Barry et al (2003) suggest that Irish MNEs do not exhibit the normal proprietary assets associated with the horizontal multinationalisation of the firms. They point to the difficulties facing firms in late-developing regions in surmounting FDI entry barriers. This strengthens the case for government intervention in facilitating investors and seeking to reduce the impact of imperfect market conditions.

Perhaps the first objective of any government intervention must be based on an informed and constructive debate on the impact of outward FDI on the Irish economy. As argued above, this is an important dimension of economic governance, given Ireland’s status as a net outward investor of FDI. Responding to concerns that outward FDI is the relocation of Irish jobs to a third country, arguments proposed by commentators such as Navaretti and Venables (2004) to the effect that outward FDI actually strengthens economic activity in the home economy could be drawn on. The case of the US could be cited. It is the source of most outward FDI, yet it is the largest global economy. Arguments could be advanced that the goal of assisting Irish firms to invest overseas would be to protect the higher value, more skilled employment, with a focus on maintaining head office, R&D and core functions in Ireland.

Consideration might also be given to the expansion of the Government’s Asia Strategy to incorporate the facilitation of outward FDI. IBEC (2006: 63) argues that ‘Asia clearly shows potential for increasing outward foreign direct investment by a number of Irish companies’. The focus of an expanded Asia Strategy could be on providing information and assistance to medium-sized firms that wish to invest overseas, sponsoring missions of potential investors, matching potential investors to projects, and giving financial support for feasibility studies All forms of international activity are management intensive, foreign investment particularly so. Information gathering, a crucial part of the feedback process, is particularly time intensive. IBEC (2006) found that China scored the highest of the twelve Asian countries included in its research on a lack of market intelligence. The comment by one executive of a firm which has invested in Eastern Europe but not in China, that the management team did not feel competent to deal with the challenges associated with investing in China, points to the desirability of some form of government assistance. In addition, ‘small firms face a high degree of risk in going international, it is likely that the proportion of resources committed to a single foreign direct investment will be greater in a small firm than a large one’. (Buckley, 1997: 35) Consideration could be given to putting in place a range of services for investors, similar to those identified in table 8 above, with a view to providing market intelligence and support for those Irish firms which wish to invest in China.

All Irish and non-Irish participants bar one saw no role for the home country government in providing financial support to investing MNEs. They were of the clear view that it was inappropriate for home governments to subside investment overseas and that investment should be undertaken based on clear economic rationale. However, all executives envisaged a role for home government ‘soft’ supports to varying degrees.

Utilising the analytical framework of state supports employed by the IFC, as set out in table 8 above, the executives of Irish MNEs interviewed within the framework of this research identified the need for a greater provision of information by state agencies. In addition, the lack of assigned responsibility to any state body for the provision of assistance for outward investors was identified. The lack of a specific focus on outward investment in ‘trade missions’ was raised, as were the lack of potential ‘match-making’ and funding for feasibility studies. With a very slight re-focussing, the introduction of these services would assist Irish MNEs in their endeavours to invest abroad.

Specific issues of note were also identified by this research. The most significant locational challenge identified by executives is the potential threat to intellectual property, which investing in China poses. Government has a role to play in lobbying for greater protection for this ownership advantage. It is probably fair to say that most lobbying on this issue is undertaken by the European Commission on behalf of EU member states, and by the European Chamber of Commerce. Perhaps a role exists for concerted lobbying by individual EU governments in addition to the role played by the European Commission. There is a temptation to leave issues such as this to the European Commission, as trade is a competence of the European Commission. However, concerted action is likely to lead to stronger results. Lobbying at governmental level is also required when national treatment is denied to foreign investors.

Managing government relations is an important dimension of investing in China which Irish investors would be unfamiliar with. While China is a transition economy, it maintains many of the hallmarks of a centrally-planned economy. Government tends to intervene in the economy to a greater degree than in western economies. (Robins, 1996) Osland (1994) argues that, when operating in an economy with an element of arbitrariness in decision-making, maintaining good relationships with officials is critical to long-term success. Robins (1996) points to the close involvement which the Chinese authorities maintain in the economy and their willingness to intervene and manage markets.

All executives acknowledged and were deeply appreciative of the role played by diplomatic missions and state agencies in assisting entry into the Chinese market and in facilitating contact with relevant Chinese officials. The location of diplomatic missions should be reviewed periodically to assess if additional locations are required to reflect emerging Irish investment location patterns in China. The findings of this research are supported by IBEC (2006: 63), which found that ‘over half of the companies surveyed found the support offered by Diplomatic and State Agency offices important or critical’. It was also found that these supports were perceived as relatively more important to companies doing business in Asia than elsewhere.

The policy of providing limited venture capital merits further consideration. An Irish MNE specialised textile manufacturer found it difficult to raise capital. It was only after the state agency responsible for the promotion of trade decided to invest that it proved possible to raise the required capital. The State may be required to take on such a role on a case-by-case basis. Enterprise Ireland commonly takes a shareholding in start-up companies in Ireland. There may be a need to extend this practice and actively take a shareholding in firms which wish to invest abroad, but only in cases where this would result in the maintenance and strengthening of the Irish base of operation. Such an investment should be undertaken only in firms which can exhibit that they possess ownership and internalisation advantages.

Governments also have a role to play in providing the legal infrastructure to facilitate FDI. At the end of 2006 there were 2,944 double taxation treaties globally (International Bureau of Fiscal Documentation), pointing to the importance which governments attach to this issue. Jun (1989) identifies three channels through which tax policies affect the decisions taken by MNEs. First, the tax treatment of income generated abroad has a direct effect on the net return on FDI. Second, the tax treatment of domestic income affects the profitability of domestic investment. Finally, tax policies affect the relative cost of capital employed in FDI. By using an inter-temporal optimisation model, Jun shows that an increase in the domestic corporate rate of tax leads to an increase in the outflow of FDI.

What is important is the existence of a double taxation treaty with the country in which they are investing. Ireland has 41 double taxation treaties, including one signed with China on 19 April 2000. (Department of Finance, 2006)

However, Ireland does not have a Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) with China. In fact, Ireland has only one BIT, which was concluded with the Czech Republic in 1996. In comparison, 19 of the EU’s 25 member states have BITs with China. In fact, of the EU15 (member states prior to the May 2004 enlargement), all of the other 14 have BITs with China. (UNCTAD, 2007) Ireland’s policy relating to Bilateral Investment Treaties was discussed with a senior official in the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment. He set out the Government’s general policy that multilateralism is the preferred framework for issues of this nature, given our membership of the EU. He stated that there are many EU trade and competition regulations which impinge on investment treaties and which have to be taken into account. When third countries suggest a bilateral investment treaty (BIT), the Department declares its preference that the country should negotiate a comprehensive agreement with the EU, which will have legal effect in Ireland.

The Chinese authorities attach considerable significance to the signing of international agreements as a visible expression of friendship between two nations. The author has witnessed this penchant for signing Memoranda of Understanding during trade missions. While there are very valid reasons why Ireland does not negotiate BITs, perhaps consideration could be given to evaluating the potential merits of such a treaty with China, given its status as the prime location for inward FDI.

The challenge facing the Irish Government is to manage the impact of the increasing levels of outward FDI in order to ensure that core technology remains in Ireland and that higher value employment is created, while at the same time strengthening Irish companies to enable them to compete in the global economy. The Government can assist by providing information and expertise to companies which wish to invest in China’s challenging market. This should not be seen as advocating the movement of large tranches of the Irish industrial base to China. Rather it is a recognition of the market opportunities which China offers to Irish indigenous companies which possess the required ownership and internalisation advantages, as a means of further strengthening the Irish industrial base.

Conclusion

As indicated above, Irish FDI in China does not conform to Barry et al’s (2003) model that Irish outward FDI is disproportionately horizontal and largely in the non-traded sector. Irish FDI in China is predominately in the traded sector and marginally horizontal. While it is difficult to precisely identify trends, it is clear that there has been no significant change in this pattern since 2007 and there is unlikely to be a shift in the near future. In the medium term there is the possibility that the nature of Irish FDI will alter as the service sector develops in China. The extent to which Irish MNEs can exploit this development depends on the level of ownership and the internalisation advantages which firms in these sectors possess.

Based on the locational disadvantages which China poses, the market imperfections which exist, and the potential to expose the ownership advantages of Irish MNEs to risk, a role exists for state intervention. There is merit in the government’s engaging in a policy debate on the nature and impact of Irish outward FDI, particularly in view of Ireland’s recently-acquired status as a net exporter of FDI. Given China’s pre-eminent ranking as the largest recipient of inward FDI, the effect of outward Irish FDI to China, as well as FDI to traditional FDI destinations, merits further consideration.

NOTES>

[i] An example of this is the relocation from Europe and the US of moulds for the production of obsolete car models for sale in the Chinese market. Given the substantial cost involved in producing moulds, this represents a saving to car manufacturers.

[ii] This is measured by an average of four shares: FDI inflows as a percentage of gross fixed capital formation for the past three years; FDI inward stocks as a percentage of GDP in 2003; value added by foreign affiliates as a percentage of GDP in 2003; and employment of foreign affiliates as a percentage of total employment in 2003. (UNCTAD, 2006: 11)