The aim of this paper is to remind modern researchers studying modern, post-Soeharto Indonesia of the research on the history of political capitalism in Asia, including the Indonesian Archipelago done by the Dutch scholar Van Leur. While preparing his well known thesis on the Asian Trade system, he concluded that the Indonesian island group has a bipartite geopolitical structure. This structure consists of a maritime zone of sea routes and coastal urban centres dominated by local and interregional political capitalism, and a peripheral part that stands partly on its own and is in part connected to the first zone. The question he asked was why the Asian type of political trade capitalism had been able to survive for such a long time and had even had been continued by the V.O.C., while in Europe this form of capitalism had long disappeared.

The aim of this paper is to remind modern researchers studying modern, post-Soeharto Indonesia of the research on the history of political capitalism in Asia, including the Indonesian Archipelago done by the Dutch scholar Van Leur. While preparing his well known thesis on the Asian Trade system, he concluded that the Indonesian island group has a bipartite geopolitical structure. This structure consists of a maritime zone of sea routes and coastal urban centres dominated by local and interregional political capitalism, and a peripheral part that stands partly on its own and is in part connected to the first zone. The question he asked was why the Asian type of political trade capitalism had been able to survive for such a long time and had even had been continued by the V.O.C., while in Europe this form of capitalism had long disappeared.

Today these questions once again become interesting as we become progressively aware that, on both the national and the regional level, the Soeharto regime that fell in 1998 was fuelled by a type of political capitalism that came close to what had existed during pre-colonial and early colonial times. And thus the question of the continuity of political capitalism returns to the agenda of modern Asia research.

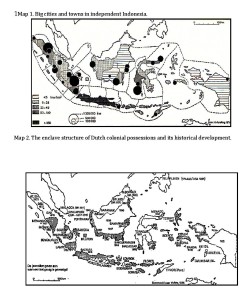

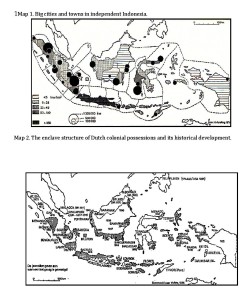

In the introduction I pointed out that Indonesia’s recent ethnic tensions occurred especially in the coastal cities and coastal areas where Indonesia’s strategic resources are located, and not to any great degree in the interiors of the major islands. In the course of Indonesia’s long history, many ethnic groups have evidently settled in and around the coastal cities, where they live together. This geographical curiosity has its roots in Indonesia’s past as an international emporium and trade port in the overseas trade between India en China, as well as at certain times between Asia and Europe. This trade needed ports of call [i] under the control and protection of local rulers. These rulers allowed foreigners [ii] that contributed to the settlement’s trade to settle in their own wards with their own heads and courts. These wards had a certain measure of diplomatic immunity, turning the ports of call into places with an international population. In this context, foreign businessmen and traders became the driving force behind maritime Asia’s coastal economy. The geographical position of the urban settlements in the archipelago and their mixed populations has not fundamentally changed in the past two thousand years, as is evident from maps 1 through 2.

The question that arises from this historical continuity is whether the underlying political and economic systems have remained unchanged as well. The answer is partly yes and partly not. Partly yes, because, as will become clear in this chapter, the central organizing factor behind the distribution of coastal cities and ethnic communities has been political capitalism, both then and now[iii]. Partly not, because the modern form of political capitalism in Asia, to wit the nationalistic side of the modern nation-state, subjects everything within its borders to its authority and mistrusts foreign businesses and capital because of their excessive power in the world-markets and their danger to the domestic market.

Van Leur’s hypotheses in a nutshell

The best way to begin an analysis of the historical lines of power and capital formation in the Indonesian Archipelago and their effects on processes of migration, settlement, and local community formation is to discuss a few hypotheses from the dissertation of the pre-war Dutch historical sociologist, J.C. van Leur (1934). This work considers the millennia-old Asiatic coastal trade, in particular the part played by the pre-colonial Indonesian states. Partially as a result of W.F. Wertheim’s 1955 English translation of this dissertation, which was reprinted in 1967 and 1983, Van Leur’s analysis also came to receive attention outside The Netherlands.

There are several reasons for discussing Van Leur’s analyses of Asia’s overseas trade and the accompanying political capitalism. He was the first and is still one of the few Dutch historical sociologists to tackle the history, sociography, sociology, and anthropology of the Asian coastal trade as a single topic. Moreover, his analysis contributes fruitfully to the basic theme of the current book, namely the cultural and ethnic diversity of Indonesia. Van Leur’s analysis especially considers:

[a] the historic patterns of the inter-regional overseas trade and

[b] the founding of multicultural urban forms of political capitalism: coastal cities and states,

[c] the distribution across commercially active coastal settlements in the Indonesian Archipelago of ethnic communities and individuals through spontaneous migration.

Of these three processes he considered the second to be most important. Van Leur combined these three factors in a single hypothesis, namely that pressure by local power-holders lead the overseas coastal trade in Asia and the Indonesian Archipelago to cause urban ports of call, colonies of migrants, and coastal states to come into being along the trade routes.[iv]

Also characteristic of pre-colonial Asia, according to Van Leur, was that political leaders were religiously ordained and internationally acknowledged Hindu and Buddhist rulers. The separation of church and state was unknown in Asia’s urban political capitalism as was the separation between the state and the economy. This encompassed, moreover, exactly the problem that the West European urban bourgeoisie had been fighting against since the crusades, namely royal interference in civil matters. Research in Asia, according to Van Leur, thus demanded a research plan all its own, namely one that would help explain the continuity of a situation that had existed in the Middle East, the Mediterranean area, and Asia in ancient times as well as in the beginning of the Christian Era It had continued to exist in Asia while being displaced in Southern and Western Europe during the second millennium to make room for the development of urban bourgeois capitalism. This situation could be briefly characterized as the continuing fight by local elites to gain control over and exploit serviceable status-groups like peasantries, manual laborers, artisans, tradesmen, and travelling traders. Van Leur continually characterized this situation in negative terms: ‘No “free trade”, no “world market,” no “export industry,” no proletariat, …’ (Van Leur 1934:68ff). In other words, a situation that was in no way to be described and explained in modern economic or political terms.

In this regard he was also interested in the question of the reason that Java’s pre-colonial kingdoms of the eighth and ninth centuries had produced such beautiful edifices as Prambanan and Borobudur, when such architectural achievements were lacking outside Java and elsewhere in Asia. A careful reading of his dissertation shows that he proposed two factors to explain this, namely the availability of wet-rice agriculture and peasant labour, and the desire of the Javanese kings for recognition as Hindu rulers. In that framework the cities along Java’s north coast played a logistic and fiscal role.

The terms bourgeoisie and middle class

In Van Leur’s dissertation, the term “middle class” hardly occurs. What he does use is the term word “bourgeoisie.” He uses this term to compare the Asiatic coastal cities with those of Western Europe of the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. If one reads his dissertation carefully, one soon finds that this word was used to refer to the inhabitants of a loose collection of wards inhabited by foreign visitors that in the Asiatic coastal cities lay beyond the walls of the kraton (palace) of the local ruler. The thing that unified these inhabitants as a single economic phenomenon was at the same time the reason for their presence, namely,

(a) the overseas trade in status goods

(b) The services they provided within that scheme for members of the local elite and sometimes also to the local ruler.

Socially, linguistically, religiously and culturally the wards differed enormously from each other, and there is nothing that guaranteed the homogeneity of each ward in terms of region of origin, religion or language.

The core of each ward consisted of travelling traders, business men with a local office and storage, money lenders, sometimes also bankers, ship owners, innkeepers and the like. This mix of residents is strongly reminiscent of what Van Leur’s intellectual mentor, Max Weber, had called an ‘urban middle class’: shipowners, entrepreneurs, merchants, traders and bankers, but also including the professions, farmers and crafts men (Weber 1964 I: 224-225). The only thing was, Weber hesitated to use the word “class” for this irregular assembly.

In his view, the middle class was not a class in the usual sense of the word, but rather a privileged ‘ Erwerbsklasse’ or acquisition-class.

The reason for this is that the Erwerbsklasse is not a social class, because both socially and professionally the middle class is heterogeneous and disjointed. It is neither a class of property owners nor one of producers. Its function is Erwerb or trade, that is to say, promoting the circulation of goods, monies, services, and persons. In that sense, Weber saw the middle class as consisting not only of entrepreneurs, ship owners and bankers, but also of professionals, shop keepers, farmers, and craftsmen.

As I pointed out, in this Weberian sense of the word, local urban middle classes certainly did exist in Asia. Only, they did not administer cities, as had been the case in Western Europe in the Late Middle Ages and beyond. After all, they were foreign guests of the local rulers rather than self-governing citizens of cities

In classical Western economics the term “middle class” has acquired a very specific ideological meaning, namely one of a class of free civil entrepreneurs whose activities are a series of actions aimed at the formation and growth of capital, based on the proper registration of expenditures and incomes through double-entry bookkeeping (costs and profits). Classic economists consider this class to be the engine behind the emancipation of Europe’s civil society and the industrial revolution and progress that resulted from this. The presence of this class in a country is considered to be an absolute precondition to the development of capitalism. According to Van Leur, this kind of middle class did not exist in Asia, neither before nor during the colonial period, even if the historic urban middle classes in maritime Asia most certainly counted on the formation of capital and on entrepreneurs, merchants and traders in their midst that aimed at the growth of capital. However, not they but the coastal rulers were the driving force behind Asia’s trade-capitalism. And here we are faced anew with Van Leur’s question, why traders and entrepreneurs in the coastal cities continued to virtuously serve the local rulers and did not demand self-determination, as had occurred in Western Europe during the second millennium.

In what follows we will more closely examine the building blocks of Van Leur’s analysis of Asiatic trade and Java’s political economy. At the end of this chapter we will briefly consider the role of European expansion in Asia between roughly 1600 and 1956 C.E. in the decline of the welcome received by foreigners and immigrants in the Indonesian Archipelago.

The geographic structure of political capitalism in the archipelago

To properly understand the importance of Van Leur’s analysis of Asiatic trade and Asian political capitalism, we must first consider the geographic structure of the Indonesian Archipelago. The millennia-old pattern of Asiatic overseas trade was based on a series of three navigation routes, namely the Straits of Malacca, the Java Sea, and the Banda and Seram Seas. For as long as local historical sources go back – and that is quite a long time – this pattern had been Indonesia’s import-export zone. Within this zone we still find the great majority of Indonesia’s cities and 100% of her large cities and harbours (compare map 1).

The population of the cities in this zone is multi-cultural as a result of overseas trade and immigration. They are located in densely populated, prosperous economic enclaves along the major international shipping routes. Map 2 shows the history of incorporation by the V.O.C. and the Dutch East Indies, which shows a comparable pattern of enclaves.

This situation is an inheritance from the past in two ways. In the first place, in the past, even far into the twentieth century, travel meant travel over water, e.g. over rivers and the sea. Roads did not exist or existed only near villages, plantations and cities. What roads there were, were unsuitable for the regular and large-scale movement of persons and goods. [v]

This situation is an inheritance from the past in two ways. In the first place, in the past, even far into the twentieth century, travel meant travel over water, e.g. over rivers and the sea. Roads did not exist or existed only near villages, plantations and cities. What roads there were, were unsuitable for the regular and large-scale movement of persons and goods. [v]

Second, cities only came into existence in places where members of different communities met to trade goods and services, and that occurred at the intersections of the usable water-ways (navigable rivers and sea lanes): at the mouths of rivers. Beyond that there were natural road steads and harbors that encouraged contact and trade (Krom 1931:74-75).

There, foreign traders sold their goods to other, local traders or to local elites. Fellow countrymen sought each other out and settled in ethnic wards. In this way there developed a combination of on the one hand a local, spontaneous apartheid, a spontaneous and natural (primordial) form of urban ethnicity, and on the other a local bazaar-trade. Where immigrant men came alone, sexual relations with local women occurred as well. Local rulers living in fortified palaces or kraton protected this combination of navigation, coastal settlements and trade.

According to Van Leur, this form of leadership had its roots in the nature of the Asiatic trade itself, which in essence was a combination of coastal navigation and travelling traders. The ships were small and were propelled by a combination of rowers and sail. With the exception of the large Chinese junks, which had already navigated the Asiatic seas in the first millennium, these ships had no cargo holds, but secured their freight on deck with ropes, including the provisions and fresh water needed while at sea. It is no wonder, then, that this coastal trade had need of ports of call to take on water and provisions, to take on or off-load traders and their wares, or to find refuge from storms or pirates. All these practical matters called for local safety and political protection, attracting both local and international political leaders, willing to act as patrons of the ports of call (Van Leur 1934).

An important factor determining the rise of ports of call in the archipelago was the difference in the direction of the wind above and below the equator. If a ship were to sail above the wind, from India to China, and had to enter the archipelago, it moved across the equator where the direction of the wind changed, causing it to sail in the other direction. In the Straits of Malacca this meant that ships were driven toward the coast of Sumatra where the crew had to wait for the next monsoon. When they crossed the equator again, they had to wait once more for the west-monsoon, allowing them to continue the journey to China. All this took much time and a trip from India to China with a stopover in the archipelago could take as much as four years.

With that we arrive at the history of the development of the larger and smaller kingdoms of Asia, which came and went with regularity during the first millennium C.E. The primary source of income for local rulers and kings was skimming the wealth of the passing Asian coastal trade: forced transhipment, tribute, protection money and monetary income, and if these were not paid ‘voluntarily,’ robbery and plunder were another option.

When it seemed lucrative, these leaders and elites also participated in the trade themselves by commissioning traders (commenda), cooperating with foreigners to make a profit. This led to the development of patronage relationships between local leaders on the one hand, and foreign rulers, strangers and local ethnic status-groups on the other. According to Van Leur, therefore, political capitalism, patronage and ethnicity are the framework within which pre-colonial Asian trade must be seen.

The consequence of all this is that historically we must see Indonesia not so much as an archipelago: a disconnected assortment of islands ruled by local heads and little kings. It was first and foremost a system of waterways with coastal ports of call, places of storage and markets, centres of power, and secondary passages like sea arms and rivers. The islands lying beyond this system were a ‘frontier area,’ a border-zone with the rest of Asia. This dualistic framework of local Asiatic political capitalism, in both the pre-colonial and the colonial periods, was the political heritage that the Indonesian government had to find a way to exploit after independence.

Small-scale trade and accumulation

In the following paragraphs we will deal with two questions raised by Van Leur’s analysis of the historical and systematic relationship between the Asiatic coastal trade and the formation of local power. These concern (a) the Asiatic coastal trade’s ability to accumulate capital and (b) its relationship with non-commercial spontaneous migration. Let us start with the first question.

Van Leur characterized the Asiatic coastal trade as small-scale. With this he meant that rather than being an unaccompanied bulk-trade in mass-consumption goods, this commerce was based on the labours of travelling traders moving small quantities of expensive prestige goods, either on the orders of powerful men or on their own initiative. The question raised by this picture is as follows: if in terms of volume the coastal trade was small-scale, how could it have contributed to the development of large, powerful kingdoms like the Sumatran Srivijaya? Very briefly, Van Leur’s answer is that during each monsoon, many traders and ships were involved in it, together making possible a relatively rapid accumulation of wealth, comparable to that raised by bulk-transport.

“One is constantly struck by the large number of traders, the bustle on shipboard and in the harbours, the trading voyages with hundreds of merchants. In every port town there were foreign quarters, colonies, courts, fondachi. Trade, still embedded in age-old forms of mutual aid, involved many people grouped according to city and region of nativity and ancestry. The long duration of the voyages made settlements necessary at the ‘stages’ in foreign lands” (Van Leur 1955:66).

The English translation of the word ‘kramer’ or ‘marskramer’ by (travelling) ‘peddler’ has led to discussion and misunderstanding. ‘Marskramers’ are travelling peddlers that carry their wares on their backs. The metaphor of the ‘marskramer’ is somewhat infelicitous because in English-speaking areas, such persons are nonentities, something the Asiatic traders certainly were not. Van Leur was aware of the modern connotation of poverty attached to the idea of ‘marskramer’ and posited that:

“It would be completely incorrect to visualize for that peddling trade the picture of poverty it evokes at the moment. Though the trade was a trade in craft forms, it was international trade in valuable high-quality products; though there were comparatively few transactions involving comparatively little merchandise, the value of the turn-over was very high” (Van Leur 1955:67).

This does not take away the fact that Van Leur also was of the opinion that:

“… for a true historical picture one must link that trade with the poorest remnants of the international peddling trade still to be encountered in Europe in the venders wandering from door to door and the hawkers at fairs selling rugs and worthless trinkets. Their goods-in-trade are now for the most part by-products of modern industry, and their trade is a miserable business of begging. Nevertheless it there the related forms are to be found” (Van Leur 1955:63).

Each transaction could yield a lot of profit, albeit that, as was pointed out, this involved a lot of time. Jan Huygen van Linschoten figured that a journey from Holland to China and back would take three years and yield a profit of a hundred to a hundred and fifty percent (Van Leur 1955:64). Given the large number of persons participating in the trade – the harbours swarmed with ship-owners and captains seeking freight, and traders looking for goods – much business was conducted in the overseas Asiatic trade. The crux of the story, however, is that the Asiatic trade was one carried on by rulers and elites, that supplied a market made up of rulers and elites and was based on a hierarchical system in which travelling traders occupied the same position as tenant farmers. It was only with the coming of the Europeans that economic phenomena like “commodity,” free civil entrepreneurship, rational accounting and business methods as well as “bulk trade” gradually became known in Asia, albeit that they were accompanied by ships cannon, soldiers and monopolies.

Post-war critique of the concept of “peddler”

After the war, Mrs. Meilink Roelofsz turned against Van Leur’s conception in her dissertation (1962). According to her, numerous powerful, international Muslim trading concerns were involved in the sixteenth and seventeenth century sea trade in Southeast Asia, dominating international bulk-trade on the region’s seas with their large freighters. The Chinese and Indians, moreover, had used large sailing ships with much space for cargo as early as the first millennium. The Chinese junks that first sailed the seas in the eight century C.E. are still a daily phenomenon in Asia. Their cargo space served to transport bulk-freight [vi] consisting of imperishable or less-perishable goods like wood, iron and copperware, earthenware and porcelain, as well as rice and tea. Within the archipelago the trading vessels transported bulk and luxury goods between the islands (Meilink Roelofsz 1962: 5-7).

Actually, the picture Meilink Roelofs sketches here is reminiscent of the West European overseas trade in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the time of the major European trading concerns using double-entry bookkeeping that specialized in the bulk trade in spices, sugar, and Chinese earthenware in Asia, and sugar and slaves in the west.

But, if we read Van Leur’s dissertation carefully, in typifying Asian trade he was not so much concerned with the size of the ships or the existence of large trading concerns and moneylenders, because as he saw it, Asia had long been quite far ahead of Europe in this area. The ships that were used in the Asian trade varied from small fishing vessels and larger Indian ships to four-mast Chinese junks, with a deck and a crew of two to three hundred men and tens of passenger cabins: ships, in other words, that were clearly meant for the international trade. Asian trade indeed led to the development of trading concerns that were larger than those of the Fugger-concern of fifteenth century Europe and had a more extensive network of creditors (Van Leur 1934: 21, 58, 81, 85).

Van Leur, however, was concerned with the way in which pre-colonial transport took place practically, that is to say, on the level of the travelling trader. Voyages were long and there were many dealers, all moving expensive goods (Van Leur 1934: 71, 91). This phenomenon precluded bulk trade in the sense of unaccompanied, loose mass-shipments from a shipper to a customer. From recent finds in Asian shipwrecks, among others from sixteenth and seventeenth century Chinese junks, however, we know that on the orders of the V.O.C. and other European trading concerns, there was much bulk transport of Chinese earthenware and porcelain. It is imaginable, therefore, that the involvement of the Chinese junks in the European trade also promoted the development of bulk trade by Chinese trading concerns.

Asiatic trade and migration

The second question arising from Van Leur’s vision of the Asiatic coastal trade concerns the connection between this trade and migration. The reason for this is that the large geographical distribution of numerous cultural communities in the Indonesian Archipelago, to which among others the Indonesian Republic’s motto ‘Unity in Diversity’ refers, must also have come into being as a result of overseas sea trade. Was non-commercial traffic not connected with the Asiatic sea trade or was there a connection?

In this regard he noted that he saw the trade routes as the channel along which processes of migration took place that had developed in Asia and the Indonesian Archipelago after the last ice age, as well as the reverse. Migration also always has economic motives. Van Leur differentiated three kinds of migration that contributed to the colonization of the islands of the Indonesian Archipelago after the last ice age, especially of the coastal areas. These are:

[1] the migration of large groups leaving certain areas and settling elsewhere,

[2] the migration of individuals, in which especially the Asiatic coastal trade and the settlement of stranger-traders is concerned, and

[3] the founding of daughter-settlements or colonies of local communities and of new political centres elsewhere in the archipelago (Van Leur 1934:124-126).

The results of the first type of migration can be seen in Minangkabau and Malay colonies: on Sumatra’s north and south coast, in the Malay river valleys (Riau), east of the Minangkabau highlands, in the Malay mainland (the Malacca peninsula), in Madagascar, perhaps in Timor, and further in numerous other islands in the archipelago. Also included, furthermore, are the Buginese settlements in South Celebes, Riau and Northwest Kalimantan as well as the numerous Chinese coastal communities in Indonesia.

In Van Leur’s terms these are cases of a “people’s colonization,” consisting of emigrants from a certain part of the archipelago that settle elsewhere. Trade may have played a role in this, but in the end people were especially concerned with starting a new life elsewhere, with or without the retention of the original culture (Van Leur 1934: 124).

The second type of migration brought individual strangers from outside the archipelago to the coasts along the major trade routes, finding shelter in communities (kampung) of their compatriots. These communities had their own administration and leadership, their own system of justice and a certain degree of extraterritorial immunity (Van Leur 1934:124-5). This was the route by which Chinese, Arabs, Indians, Cambodians and all those other traders entered the archipelago. They married local women, either from within their own group or from local indigenous communities.

Finally there was the migration that was accompanied by the formation of new centres of power in the archipelago, such as the Malay coastal states in Borneo, the Buginese states in East Sumba, West Flores, the Riau and Lingga archipelagos, and Bali’s control over Lombok (Van Leur 1934:125; compare map 3). Within this third category we can also place the seventeenth century rise of the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (V.O.C.; the United Dutch East Indies Company), and the takeover of its interests through Dutch colonization at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century.

The historical framework within which the overseas Asiatic trade occurred, therefore, was not purely commercial, but rather a mixture of the overseas migration of peoples and coastal trade on the one hand, and of local and international power politics on the other. It was this mixture that would eventually make the archipelago into the multi-coloured, non-territorial ethnic quilt that it is today. The common factor in this diversity was that the routes taken by the communities, the freighters, and the leaders of expeditions were in fact identical and formed the connecting link between the same areas.

As far as the archipelago’s cultural communities were concerned, the final result was two-fold. On the one hand there were the overseas settlements of members of certain home-communities, such as Malays, Javanese, Balinese, Buginese, Makasarese, and Minangkabau, who lived in urban enclaves along the most important waterways of the archipelago’s Asiatic trade, such as the Straits of Malacca, the Java Sea and the Banda Sea. On the other side there were the little archipelagos with their own systems of trade and the ‘homogeneous’ home-communities without overseas colonies that were found in the interiors of the larger islands, the smaller archipelagos and on the periphery of the area in which the Asiatic trade took place. This historical geographic division of urbanized coasts, small archipelagos, and periphery can be clearly seen in maps 1 and 2 of this chapter: from major population concentrations in the West of the archipelago to lower ones in the East and away from the sailing routes.

Banten, a multicultural coastal state

An example of a pre-colonial coastal state is the sixteenth century sultanate of Banten. In the walled royal residence in the coastal states lived the ruler and his court and the political elite. Outside the wall in open wards stood the houses of the foreigners, who together were the clients of the ruler and the elites. Over time some of these cities grew into ‘metropolises.’ At the end of the sixteenth century, Banten, which was located in the western part of Java, was a transhipment point and terminus for trade in the whole Indonesian Archipelago. The economy of the city of Banten was an international warehouse one, consisting of foreign ethnic communities that were in contact with each other in the market, at home, in the street, and via their local leaders.

The loose collection of foreign ethnic communities that was Banten fell under the local elite with their following, above whom in turn stood a ruler and his family. Due to a lack of local labour, the Banten elite used slaves. Many foreign traders visited the city or had settled there. In the busy markets one could find Urzen [??] from Khorasan, selling jewels and medicines, as well as rich Gujeratis from India importing linens and tamarind, and Turks and Arab quite experienced in trade. Portuguese, that is to say Indo-Portuguese from Malacca, wore long Persian trousers and walked barefoot. Slaves carrying parasols (payung) to raise their prestige followed them through the streets. They chose their servants from among the different nationalities living in or visiting the city. In this way they always had a translator at hand when visiting strange notables from “foreign” kampung. Also found in Banten were Peguanese, that is to say people from Pegu in South Burma, a strange people that came to Banten every year to trade there. They probably were the importers of the city’s elephants that could be hired as work and draught animals.

Malays, and Klings from India were highly honoured, lent money both at interest and for a predetermined fee, the last especially to Abyssinians, who tended to be poor sailors. Klings and Cambayers also supplied many cotton dresses and white cloth that was batik-ed by Bantenese women or was stitched with gold threat. Bengalese especially sold semi-precious stones and cheap goods. The Chinese, finally, occupied the grandest houses in a ward of their own that lay outside the city walls, to the west. Different from the other wards, a wall of wooden posts surrounded this one. To safeguard them from fire and danger, the Chinese were also the only foreigners to live in houses made of stone. Other houses were made of wood. It were especially the Chinese who went in to the interior to buy pepper, Banten’s main product, armed with a weighing-beam (Dutch: unster), a stick along which weights could be moved back and forth. About the time that Chinese ships were expected on Banten’s roadstead, they brought the pepper to the port city. The emperor of China had bought off the Portuguese who competed with his subjects in the pepper trade, so that the Portuguese could only trade in cloves, nutmeg, mace, sandalwood, peppers, cubeb-pepper, and all manner of medicines for linens imported from Malacca.

The Chinese occupied a strategic position in the area of import. In the first place, they imported the coinage that became accepted throughout Java, namely the picis or pisis, thin lead coins with a square hole in the centre. A thousand of these coins were equivalent to twenty nineteen thirties’ cents. They also imported both fine and ordinary porcelain, silk cloths, damask, velvet, satin, silk thread, gold thread, gold cloth, needles, combs, eye glasses, parasols, slippers, mirrors, fans, beautiful chests, paper, almanacs, gold leaf, mercury, copperware, Japanese swords and medicines.

Chinese exports consisted of pepper, indigo, sandalwood, cloves, nutmeg, turtle and ivory. Chinese living in Banten made gold en gold-plated casks, though these were not as nice as the ones made in Bali.

From Banten everything was distributed around the archipelago. Javanese and others came to obtain cargo in Banten and brought their own merchandise there on the way in. In this way, in Banten one could purchase salt from East Java, palm sugar (gula Jawa) from Jacatra and Japara (the north-cape between Central and East Java), as well as rice from Macassar (South Celebes) and Sumbawa. Rice was something the Bantenese needed badly because their soil would only produce a quarter of what was needed. The area around Banten itself, however, produced ships’ supplies like chickens, eggs, fruit, and fish, but no rice. These supplies were so cheap that even the impoverished Abyssinians could afford able to buy them (see Fruin Mees II 1932:39-43).

The syahbandar

Aside from the Chinese ones, there was only one other house in Banten that was made of stone. Even the royal palace was built of wood, although within it there was a large stone vault where the treasury and the royal insignia were kept: the king had much money and many prestige goods and insignia to store. This stone house belonged to the syahbandar or harbour master who regulated trade and storage in the harbour and the city as well as the associated finances and taxes. He was the king’s most important advisor in financial matters (Fruin Mees II 1932:39-43).

In general, syahbandars had an important position in all historic coastal states in the archipelago. In their area they controlled goods coming in and going out, as well as arriving ships and persons, monetary traffic and tolls. Aside from this they were the king’s most important advisors in these matters.

Some of the governors and harbour masters were foreigners, coming from other parts of the archipelago or from far-away lands. Among them were Chinese, Persians, Arabs, and Indians. Reid, for example, pointed out that many of the embassies sent to China by the famous East Javanese state of Majapahit (14th and 15th centuries), were Chinese. In this connection he mentioned names like Chen Wei-ta and Kaifu Patih Marong (Reid 1995:27). Employing these foreigners did not give rise to overriding feelings of ethnic dislike among the rulers concerned.

In the Malay coastal states along the Straits of Malacca the harbourmasters even had important positions in the court, in some cases to deep in the eighteenth century. Such a syahbandar was Habib Abdoerrachman, an Arab who had been born in 1832 in Hadramaut on the Arabian Peninsula. His career included positions at the courts of Johore and Aceh, his last position being that of governor of Aceh, in which capacity he fought a war with the Dutch. In 1878 he resigned his position and returned to Arabia with his family aboard a Dutch ship. Thus, trade and kingship were connected within the Asiatic coastal trade, also after the arrival of the Europeans in the archipelago. This was exactly the kind of thing that the colonial government tried to bring under control, preferably willingly through ‘voluntary’ submission, but forcibly through military conquest if necessary.

The difference between Java and Sumatra and Van Leur’s explanation for this

Through Van Leur’s analysis of the Asiatic trade we now have a good idea of the factors and processes that led to the development of coastal states, political capitalism and multi-cultural coastal cities in maritime Asia.

However, in the post-war literature, Van Leur’s work is especially related to what he is perceived to have seen as the exceptional position of Java. According to post-war researchers, Van Leur saw the development in Java since the eighth century C.E. of wealthy kingdoms with a penchant for building as something that could not be explained on the basis of the Asiatic trade, but had to be treated separately.

In his dissertation Van Leur indeed paid attention to the historical puzzle of how it was possible for the kingdom of Mataram to suddenly arise in the interior of Central Java in the eighth century and within a century and a half build a number of impressive Hindu-Javanese edifices, equalling those elsewhere in Asia[vii]. This was all the more amazing, because neither archaeological finds nor the Chinese imperial archives of the time give any indication of a noticeable advent of such a development. Van Leur wondered how this could have happened, and included in his speculations the presence of wet-rice agriculture in the interior of Central Java, which yielded much food and involved the presence of much labour. To this he added the presupposition that the involvement of a large farm labour-force in major building projects like Prambanan and Borobudur would also have necessitated a large army of supervisors and overseers, leading what he has called a “bureaucratic despotism.”

According to post-war readers of the English translation of Van Leur’s dissertation, this depiction fits perfectly with Wittfogel’s theory of the Asiatic mode of production. This latter theory holds that Asiatic rulers had exploited local farm labor: imperial China, tsarist Russia and Stalin’s Soviet Union. According to Wittfogel all these made use of a unique technical property of irrigated agriculture, namely its need for externally supervised cooperation. Asiatic rulers were aware of this property and used it to appropriate control over farm labour, which was thus led into a perfect trap. Thus, is was said, Van Leur was a Wittfogelian, and on the basis of this presumption it was concluded that he had formulated his description to make plausible the idea that the accumulation of political power could also take place outside of trade and world commerce (cf. Tichelman 1980: 19 ff.). Moreover, in this way a differentiation developed between Java and coastal states elsewhere, which made it possible to show two developmental routes, namely

(1) the stationary expansion of a closed agrarian command-economy that developed in Java in the first millennium C.E.,

(2) the open political economy of the coastal states that arose in Sumatra and other islands and were based on commenda, forced maritime warehousing, protection and slave labour.

Between the nineteen sixties and the nineteen eighties much research was devoted to especially the first idea [viii]

However, the abovementioned depiction of Van Leur’s vision of Java is incorrect. Van Leur was concerned with something totally different from Wittfogel’s theoretical ideas, which he moreover found vague and inapplicable. His hypothesis of bureaucratically controlled infrastructure projects realized through forced farm-labor had only a single goal, namely to answer the question about the economic and political rationale behind the differences in the social structures of Java and Sumatra. In answering this question, Van Leur was in the first place reacting to the hypotheses posited by the historians Krom (1931:88-94) and Rouffaer (1900 I: 306), which held that Prambanan en Borobudur had been built by Indian Hindu colonists. The refined Hindu-Javanese culture that was apparent in the architecture and ornamentation of these edifices in no way resembled anything that had been found in the course of pre-historic archaeological research, namely that it was a society that was to some degree organized politically and:

‘practised wet-rice agriculture along with the accompanying irrigation system, having knowledge of navigation and stars, working metal, bronze, copper, iron, and gold, and probably having access to tame kine. In parts of Java the dead were buried in megaliths in the shape of coffins and dolmen; everywhere in the high mountains of the island, terraces had been created as places of veneration, probably especially ancestor veneration, in which piles of stone with standing peaks and rough statues played a role. …Generally Sumatra must have shown great similarities to Java, although traces of yet again other combinations and of totally un-Javanese remains can also be found there’ (Krom 1931:54; compare Coedès, Les Etats:26-27).

This heritage in no way resembled anything that the two above mentioned edifices and many others in their vicinity had to offer. Van Leur put it as follows:

“The whole early Indonesian culture [in Java, C.H.] was a courtly one, the creation of rulers, the possession and exclusive craft of the hierocracy: monuments (sanctuaries, monasteries, hermitages, burial temples, tower temples, bathing places), literature, theological writings, and the study of law. The whole culture of prince and priest stood towering far above the Indonesian population. It was not its cultural possession. Its function was only to render service and to pay levies. The recollection of the ancient Near Eastern and Indian soccage state or liturgical state constantly comes to mind” (Van Leur 1955:110).

For this reason, according to Krom and Rouffaer, Javanese court culture must have come from the outside, through a process of Hiduization coming in the train of Indian colonization (Van Leur 1934:121). Krom thought this process had reached completion in the fourth century C.E. and was responsible for the establishment of colonial Indian Hindu states in Java and elsewhere in Southeast Asia (Krom 1931:88). Early on, Krom thought, their influence was limited to the centres of colonization and the upper layers of society:

‘It goes without saying that a Hinduization of the lower social strata did not, or hardly took place and that, as one moves away from the centers of civilization, Hindu influence becomes less and less noticeable’ (Krom 1931:89).

On this point Van Leur agreed with Krom, but he definitely disagreed with the colonization hypothesis because, as he saw it, it was not based on anything substantial.

In the first place no mention is made of an Indian colonization in contemporary sources, including local ones [ix].

In the second place, the transfer of Hinduism by colonists is not possible according to the Indian caste system. According to Van Leur, this kind of transfer can by definition only have been accomplished by specialists, Brahmans, and no one else (Van Leur 1934:121).

In the third place, wrote Van Leur, the Indian caste system and the ritual primacy of the Brahmans, which governed kingship and local society in India, never took root in Java, which in the case of an Indian (Dravidian) colonization certainly would have been the case (Van Leur 1934: 123-124). This meant that Javanese rulers must have utilized local craftsmen, which would have been farmers, as these were both craftsmen in their daily lives and were abundantly present. Their participation, thought Van Leur, had nothing to do with Hinduism, but rather (a) with the rice agriculture that had since time immemorial taken place in Java on rain-irrigated terraces, and (b) with the traditional relations between ruler and subject: one did what one was ordered to do. Wet-rice agriculture, after all, not only gave high yields per hectare but also made possible a high population density and thus an abundant supply of both food and labour. This labour supply was lacking in Sumatra and that is why we find no Prambanan or Borobudur there.

“The fact that Barabudur arose on Java and not on Sumatra is linked to the fact that the concentration of labour needed could be achieved on Java, in a state with soccage and an officialdom, and not on Sumatra, either in the city on rafts on the Palembang river or in the sparsely populated highlands of the interior” (Van Leur 1955:106-7).

In short, the lack of large-scale local farm labour in Sumatra explains why no major edifices were built there, but were built in Java with its great population density of rice-farmers. This also clarifies why no large-scale patrimonial bureaucracy existed in Sumatra’s coastal districts, but did in the Javanese states: because it was needed in Java and in Sumatra’s coastal states it was not.

This argument was of course also used against Krom’s and Rouffaer’s colonization hypothesis: Indian ideas were readily imported to Java but the labour to realized them was abundantly available there. According to Van Leur, the so-called Hinduization of Java must especially have been a concern of rulers and their courts, and must have been more a magical, theological matter than an institutional one. What he saw as especially attractive to the local rulers here, was the powerful ritual of legitimisation performed by the Hindu priests: “the offerings, the ordination formulae, the classical, mythological genealogy of the ruling house.” (Van Leur 1955:99).

Or, to put it in Weberian terms, the Brahmans supplied the Javanese kings and their descendants with hereditary charisma (compare Weber 1964 I:188). To experience this ritual, Javanese kings had Brahmans come temporarily from abroad (Van Leur 1934:127-133). Legitimisation [x] here means the process through which a ruler could come to call himself a Hindu king, that is to say a king who protected the norms and values of the Hinduism he represented, and displayed to his followers in an exemplary manner (compare Gerth and Mills 1959: 294).

In this process internationally recognized Hindu priests took part, which ritually and magically transformed the local ruler into, and certified him to be a Hindu king. In the process they gave him a monopoly on maintaining the local dharma, the system of justice, custom, ritual practice, law and truth of local Hindu belief [xi]. This kingship was further evaluated at set times. As Van Leur saw it, the motivation and architectural expertise for the building of Prambanan and Borobudur must have come from this international context (Van Leur 1934: 127-133).

Why foreign legitimisation?

The question now arises why, according to Van Leur, Javanese kings felt a need for foreign Hindu legitimisation of their rule. Certainly not to impress the farmers, because these were not a legitimising force within Hinduism, either in India or in Java. The only conceivable strategic reason for such a foreign legitimisation, according to Van Leur, must have been the deep impression that the sacral legitimisation of Hindu-Javanese kings made on Indian visitors. In addition, the Indian priests furthermore supplied them with a mythological Indian genealogy (Van Leur 1934: 123-124). The beautiful edifices that the first Javanese rulers had built must have multiplied the impact.

They showed such a ruler to be a proper upholder of law and order (dharma) and a trustworthy protector to visiting ships and traders from international Hindu circles. This kind of recognition, therefore, was good for foreign trade as well, and it moreover indicated that the Hindu king was a trustworthy ally to local rulers elsewhere along the route between India and China. Hinduism at the time was an internationally popular political ideology, something like liberalism is now and socialism was in the nineteen fifties and nineteen sixties: it contained the discourse for a whole series of diplomatic and commercial exchanges between states and rulers of similar persuasion [xii].

Summarizing, Van Leur defined three criteria for the legitimisation of rulers (Van Leur 1934:127-133), namely:

(a) recognition by an authoritative foreign religious centre,

(b) historical recognition by the emperor of China. This last helped in questions of Javanese claims to forced warehousing in the Straits of Malacca,

(c) the building of prestigious religious monuments and the evident proper treatment of religions. These signs of care were the imposing forecourt of the Javanese states and the ‘calling card’ for visitors (Van Leur 1934:118, 128-133).

The crucial logistical element in the early phases of the Hinduization and Indianization of Java’s royal courts must, wrote Van Leur, have been the Indian trader’s wards in Java’s coastal cities. Although these traders were no culture-bearers, they did provide the infrastructure for the movement of Brahmans to the Javanese courts, namely ships that maintained the ties with foreign religious centres (Van Leur 1934:122). This they could only do if these centers did not consider them ‘impure,’ and saw them as adhering to the same religious faith.

In short, the development of Javanese court culture in the eighth and ninth centuries materially could not have occurred without the Asiatic overseas trade between India and China in which, according to Van Leur, the coastal cities of Java, India, Sumatra, and the Straits of Malacca must have played a strategic key role. Or, as he himself wrote:

“Authority and hierocracy, both of them based on the power to exploit the Indonesian agrarian civilization and/or international trade, dominated early Indonesian history politically and culturally. The Javanese states were examples of the first type; Çriwijaya of the second (Van Leur 1955:109).

Although in this passage Van Leur seems to treat Java and Sumatra as different types of political capitalism, the connecting “and/or” logically allows both farmer-culture and international trade to be included, as can be seen in the following paragraph.

The race for EER

The reasoning that Van Leur developed for the early Javanese rulers who desired so much to be ordained as kings by foreign Brahman is a consistent one, which can be further developed these many years later. Thus, the Javanese example that was discussed above is also valid for the Buddhist kingship pursued by the rulers of the Sumatran coastal state of Srivijaya. After all, legitimisation brought international confidence that these civilized kingdoms and not dens of robbers. They were worth entering into diplomatic relations with and to trade with. One could add to this that both the Javanese states and the Sumatran ones protected a wide range of religions, namely Saivism, Vaisnavism, Brahmaism and Buddhism, evidently ignoring no opportunity to win broad, influential support. As far as the Javanese states are concerned, this must have had to do with a consideration of their strong vs. their weak points. Their weak side was their lack of mineral wealth. Their strong side included their rice-lands, their protection of the religions, and their strategic position on the routes to the Spice Islands of Eastern Indonesia. However these kinds of considerations worked out in the course of history, the fact is, according to Van Leur, that during the second half of the first millennium C.E. a power play developed. Local rulers in Western Indonesia started a race for Emporium, Empire and Religious leadership (EER), which would come to dominate the founding of coastal states and cities in the archipelago, also during the centuries to come. For simplicity’s sake I would like to call the three factors behind this run the EER-complex. In Java this complex was connected with the building of monuments: beyond Java this was not the case, or occurred later or to a much lesser degree.

Van Leur discussed the role of the Javanese coastal cities and their coastal trade only in connection with the Hinduization and Indianization of the Javanese states. Van Leur’s well known contemporary, Krom, especially discussed their role in the first wave of the Islamisation of Java in the sixteenth century, and the role that the Majapahit’s Islamised vassal-states on Java’s north coast played in the slow decline and fall of that state between 1470 and 1520.

Provisional conclusion

Reviewing the previous paragraphs, the feeling remains that, however enlightening Van Leur’s reconstruction of Javanese royal strategy and the role played by tribute, labour service, ‘ethnic’ monument construction, foreign relations and coastal cities may be, one thing remains unclear, namely the question of how all of this got started, that is to say before the necessity of foreign religious legitimisation came to be felt and the candidates for central kingship were still warming up. Did the impulse come from within? Or from the cities? Or completely from outside, as Krom and Rouffaer thought? This is an important question because the legitimisation of Hindu-Javanese kingship had its source overseas, which meant that the Javanese candidates for Hindu kingship must have had essential and lucrative foreign contacts. On the other hand they also exploited the indigenous rice agriculture. This leads us to wonder whether the question of “what came first in Java, agriculture or trade?” is a sensible one, or whether we should think of an inclusive strategy that also took account of foreign lands.

Notes

[i] A port of call is a place where travellers can find temporary lodgings.

[ii] A foreigner was someone who belonged to another community than the own. This could be a village 10 km removed as well as someone from beyond the archipelago..

[iii] “In conformity with liberal thinking, which is interested in separating politics and economics, Weber distinguishes between two basic types of capitalism: ‘political capitalism’ and ‘modern industrial’ or ‘bourgeois capitalism’. Capitalism, of course, can only emerge when at least the beginnings of a money-economy exist. In political capitalism, opportunities for profit are dependent upon the preparation for and the exploitation of warfare, conquest and the prerogative power of political administration. Within this type are imperialist, colonial, adventure or booty, and fiscal [… capitalism, C.H ].” (Weber 1968-2:66).

[iv] Maps 1 and 2 present a clear picture of this historical distribution of settlements and of the relationship between sea-trade and settlement pattern in the colonial and post-war periods.

[v] A nice analysis of Java’s pre-colonial road network can be found in Indonesian Sociological Studies, Part two, pp. 102 – 120.

[vi] Bulk-freight is an large unaccompanied load of goods sent by a seller to a buyer.

[vii] Among others, Borobudur and Prambanan.

[viii] It is known of regional dualism, which is a specific form of regional inequality, that it tends to become stronger rather than leading the regions to become closer. However, as will be seen, little can be discerned of this in pre-colonial Java and Sumatra. Between 800 and 1300 C.E. they competed for power in the Straits of Malacca.

[ix] This is remarkable as the East Javanese chronicle Pararaton in the 13th century makes much of a Chinese punitive invasion in the East Javanese state of Singasari in 1292 C.E.

[x] From earlier royal proclamations from Kutai (400 C.E..) and Central Java (Canggal 720 C.E..) one could conclude that the inauguration as an acknowledged Hindu king took at least three generations after the publication of the first local royal inscription (compare Krom 1931:71-73).

[xi] The concept of dharma is used in an identical fashion in Buddhism (Zoetmulder 1982: 367ff).

[xii] Although Van Leur obviously was not familiar with the post-war discussion about ethnic identity and ethnic markers, it is impossible to resist the temptation to express the suspicion that these monuments were meant as ethnic signs of ‘national pride’ vis-à-vis the outside world. In this sense they resemble the national monuments that president Sukarno had built in the Indonesian capital Jakarta in the nineteen fifties and sixties (chapter 3). They are also reminiscent of both the monumental houses of the Toraja and Batak ancestral monuments in the way they reflect the pride of the local community vis-à-vis the nation, and to which local leaders and wealthy migrants contribute.