Kyrgyzstan ~ A Country Remarkably Unknown

Kyrgyzstan is a remarkably unknown country to most world citizens. Since its conception in the 1920s, outside observers have usually treated it as a backwater of the impenetrable Soviet Union.

Kyrgyzstan is a remarkably unknown country to most world citizens. Since its conception in the 1920s, outside observers have usually treated it as a backwater of the impenetrable Soviet Union.

There was little interest and even less opportunity to gather information on this particular Soviet republic. But even within the Soviet Union, Kyrgyzstan was relatively unknown. It is as likely to meet a person from Russia or the Ukraine who has never heard of Kyrgyzstan as someone from the Netherlands or the USA. As one of my informants who has a Kyrgyz father and a Russian mother said:

I was raised in Kazan in Russia and went to school when the Soviet Union still existed. The kids in school did not understand that I was Kyrgyz. I sometimes explained, but they still thought I was Tatar, or from the Caucasus. We were taught some facts and figures about Kyrgyzstan in school, but that was it.

Kyrgyzstan briefly became world news in March 2005, when it was the third in a row of velvet revolutions among former Soviet Union countries. President Akayev, who had been the president since 1990 (one year before Kyrgyzstan’s independence) was ousted, to be replaced by opposition leaders who had until recently taken part in Akayev’s government.

A few years before that, Kyrgyzstan had become a focus of interest in the War on Terrorism, because of its majority Muslim population and its vicinity to Afghanistan. The country opened its main airport Manas for the Coalition Forces, who all stationed troops there.

The lack of a solid general base of background information gives the study of Kyrgyzstan a special dimension. Researchers and audience do not share images of the country that are based on a large number of impressions from different sources. Thus, every morsel of new information becomes disproportionally important in the creation of new images, and may be taken out of perspective. It also means that the researcher does not have an extensive body of knowledge to fall back on. Questions that are raised can often not be answered, as there is no corpus of data and general consensus. This can give the researcher a sense of walking on quick sand, but it also keeps the researcher, and hopefully her audience as well, focused and unable to take anything for granted.

In this paper I will give an overview of images of Kyrgyzstan as it is portrayed in journalist reports, travel guides, and works of social scientists. This will provide the reader unfamiliar with Kyrgyzstan with a framework of background information that cannot be presupposed.

Kyrgyzstan Located

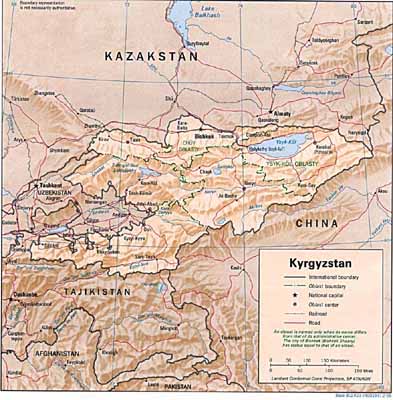

Kyrgyzstan, a country of 198,500 square km, is about the size of Great Britain. Its population of 5 million is considerably less than that of the UK, however, because of the mountains that cover the larger part of the country. Kyrgyzstan’s impressive mountain ranges, known as the Tien Shan, Ala Too and Alay ranges, are extensions of the Himalayas. Ninety per cent of Kyrgyzstan’s territory is above 1,500 metres and forty-one per cent is above 3,000 metres. Perpetual snow covers about a third of the country’s surface. Large amounts of water, in the form of mountain lakes and wild rivers, are a consequence of this landscape.

Kyrgyzstan is landlocked and bordered by four countries, three of which are former Soviet Union republics. Kazakhstan lies to the North, Uzbekistan to the West and Tajikistan to the South. The Eastern border is shared with China, or more precisely: with the Chinese province Xinjiang, home of many Turkic and Muslim peoples.

Administratively, Kyrgyzstan is divided into seven provinces (oblus, from Russian oblast) and two cities (shaar). The two cities are Osh city and the country’s capital Bishkek. Bishkek was known as Frunze during Soviet times, named after Red Army hero Mikhael Frunze. In 1991, four months before independence, the city was renamed Bishkek (Prior, 1994:42).

Kyrgyzstan is commonly divided in the North and South. The South consist of three provinces: Jalal-Abad, Osh and Batken. Batken was separated from Osh after the invasion of Islamic guerrillas in August 1999. The North consists of the Chüy, Talas, Ïssïkköl and Narïn provinces. Looking at the map, it is clear that ‘North’ and ‘South’ are not so much geographical indications, as Ïssïkköl and Narïn are at the same latitude as Jalal-Abad. A mountain ridge with very few passages, however, separates the North from the South, making them far apart in people’s experience. If one travels from Osh to Narïn, for instance, one usually takes a triangle route through Bishkek. There is a road that traverses the mountain ridge that separates them, but snow often renders it impassable. Until 1962, there was not even a road between Osh and Bishkek (then: Frunze), the railway that connected the two cities ran by way of Tashkent.

The term ‘Kyrgyzstan’ is a choice out of a number of names for the country. Presently, the official name in the Kyrgyz language is Kïrgïz Respublikasï. In English, it is ‘the Kyrgyz Republic’, after the ‘h’ in Kyrghyz was dropped in 1999. One year before independence, shortly after Akayev’s appointment as president, the Republic of Kyrgyzstan became the official name for the republic after it announced its sovereignty (Rashid, 1994:147). In May 1993, this was changed to the Kyrghyz Republic. Another often-heard name for the country is Kirgizia, which is based on Russian, who substituted the ï (usually transliterated as y) by an i to fit Russian grammatical rules. Popular in the country itself is the word ‘Kyrgyzstan’. This term is not new, but was already in use in the early days of the Soviet Union. In this dissertation, I will join with popular habit and refer to the country as Kyrgyzstan.

History of Kyrgyzstan

The actual history of Kyrgyzstan begins in 1924, when the territory was first plotted to a map. Within the larger framework of the Soviet Union, the Kyrgyz Autonomous Region was drawn up as a separate political and administrative unit. By 1936, this unit had become a sovereign Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), one of the eleven (later: fifteen) SSRs that made up the Soviet Union (Rashid, 1994:143). Of course, this delineation was not contrived in a historical vacuum but was built upon existing ideas of a certain population living in a certain area. However, the demarcation of the Soviet republics was based on choices that took certain ideas into account and left others out. A historical account of Kyrgyzstan that pre-dates 1924, then, easily falls prey to teleological reasoning. Taking Kyrgyzstan as a unit for historic research about times when the idea of ‘Kyrgyzstan’ did not exist means placing a contemporary concept which is meaningless at the time of study, as the focal point. One may begin to look for the word ‘Kyrgyz’ in historical documents and project the findings onto the group of people who are presently called Kyrgyz and who live in a Kyrgyz nation-state. Or alternatively, it is possible to project the boundaries of the territory back into the past and see coherences and connections that would not have made sense at the time. This is exactly what has happened in Soviet and post-Soviet historiography, as a part of conscious or unconscious ‘community imagining’ (Anderson, 1986). It led to a division of history into two tiers: the history of the Kyrgyz ethnic group and the history of the territory. The two do not come together until the sixteenth century, when the Kyrgyz are believed to have moved to the Tien Shan Mountains where they live today.

In a similar way, historians have projected the concept of the contemporary State back into the past. They have attempted to describe Central Asia’s history as a succession of nation-states or their equivalents. The aspiration to bring order to thousands of years of human interaction has time and again led authors to look for names of ethnic groups who formed a political unity that arose, defeated another unit and was replaced in time by yet another unit. The situation in present-day Central Asia, Siberia, China and Mongolia, however, is far more complex than that. Political units changed constantly, they covered different territories at different times, merged with other groups at one time and fought them at another time. Various ethnic groups could be part of a certain political unit or ethnic groups themselves could deal with temporarily important divisions. Furthermore, it is by no means clear how individuals perceived their ethnic, linguistic, religious and political identities. Nomadic groups especially would organise their political structures quite differently from present-day nation-states. The attempts of different authors to compile a chronology of ethnic states, then, inevitably led to differing and often conflicting time lines.

Another confusing factor is the fact that political and ethnic groups were known under numerous and varied names, and in turn other names were shared by a number of different groups. L. Krader speaks of ‘a pool or reservoir of ethnic identifications, or ethnonyms, upon which peoples could draw’ (Krader, 1963:81). Although this observation makes the use of ethnonyms seem random and arbitrary, it is indeed striking how ethnonyms continue to appear in differing contexts. The reasons that people had for using certain ethnonyms at certain times remain obscure.

The process of producing a historiography for Kyrgyzstan is further hampered by the fact that data on both the history of Kyrgyzstan’s territory and the history of the Kyrgyz people is scarce. A number of externally written sources (mostly Chinese, Persian and Arabic) have been discovered, in addition to some internal Turkic runic inscriptions and numerous archeological excavations. The lack of a firm historical framework for the analysis of these data leads to varying and differing interpretations. As most historians focus on providing a neat, complete and readable narrative, they omit confusing and conflicting data. However, when one attempts to align the pieces together in a neat and concise manner, the confusions reappear.

I will not burden the reader here with the perhaps frustrating chore of struggling through masses of foreign names belonging to ethnic groups with obscure status and abstruse interconnections. Instead, I will specify a number of historic patterns and mention those anecdotes that have become symbolic markers of entire historical periods for my informants. I will follow the method of periodisation which forms an obvious thread in this book: the periods before, during and after the Soviet Union.

Before the Soviet Union

It is within this period that a distinction between the history of the Kyrgyz and the history of Kyrgyzstan should be made. I will begin with the latter, as it is traced back further in time than the former.

History of the territory of Kyrgyzstan

Historians who concentrate on the history of Kyrgyzstan’s territory regress as far back as the Paleolithicum by identifying archaeological findings of stone artefacts and rock paintings in the Tien Shan, Ïssïkköl and Ferghana areas. These have been dated to the Palaeolithic period of 800 thousand – 10 thousand years BC (Mokrynin and Ploskich, 1995:5). The first people to have been identified by name are the Sakas, also known as Scythians. The Sakas are said to have arrived in the area in the sixth century BC (ibid.:14). They were a nomadic people who inhabited various places in a vast area from South Siberia to the Black Sea. They have been identified as being speakers of an Iranian language. According to Mokrynin and Ploskich, the North and South of Kyrgyzstan were inhabited by two different Sakas tribes (ibid.).

Three elements of this depiction of the Sakas recur in descriptions of the history of Central Asia and Siberia: they are either nomads or settled peoples, they are Turkic or Persian/Iranian, and they inhabit Kyrgyzstan’s North or South. First of all, the inhabiting groups are characterised as nomadic or settled peoples. This feature is often singled out as the driving force behind the interaction dynamics in the area. Historians discern a pattern of a continuous struggle between nomads and settlers. Nomadic groups are seen to form federations with the aim of conquering and subjugating settler groups. These nomadic federations advance over large stretches of land, looting and destroying towns and cities, until the nomads settle down themselves, form settled civilisations that are destroyed by new nomadic federations in their turn.

This meta-analysis has given rise to stereotypical images of nomadic peoples that are violent and freedom-loving versus settled groups that are industrious, religious and sustain high culture. When put to the test of the data on present-day Kyrgyzstan, however, the pattern fails. Nomadic groups often forced each other out of their territories, living peacefully alongside settler groups at the same time.

Generally, the Tien Shan mountains are seen as cradles of nomadic groups, whereas the Ferghana valley gave rise to a number of urban civilisations. In 130 BC, for example, a Chinese diplomat who travelled Central Asia found a settled group, the Davan, in the Ferghana valley and a nomadic state of Wu-sun in the mountains (ibid.:34, 44). These groups are both remembered in Kyrgyzstan by compelling anecdotes. The Davan were the owners of the legendary ‘Heavenly Horses’. The Chinese were keen on obtaining these to use them in their battles against the Xiong-nu (probably the Huns). They sent two armies to fight the Davan, in 103 and 101 BC, and only obtained the desired horses when they defeated the Davan in the second campaign (ibid.:46). Of the Wu-sun, a seventh-century Chinese writer wrote the following: the Wu-sun differ greatly in their appearance from other foreigners of the Western lands. To-day the Turks with blue eyes and red beards, resembling apes, are their descendants (Barthold, 1956:76).

During my fieldwork, I found that this comment had been modified into my informants’ frequent assertion that ‘the Kyrgyz used to look like Europeans, with red hair and blue eyes’. Interesting is the difference in assessment of the physical features – ape-like to the Chinese, which was probably a low-status qualification, and European-like to present-day Kyrgyz, that they generally regard as a high-status qualification. Also interesting is that in this case, my Kyrgyz informants traced their ancestry back to the early inhabitants of present-day Kyrgyzstan. Commonly, the ancestor Kyrgyz are considered to be a people that migrated from Siberia. It is possible, of course, that in popular historiography the comment on the Wu-sun is taken entirely out of context and transferred to the Siberian ancestors.

In later years, the area was inhabited by members of the nomadic federation of the Juan Juan (ibid.:81), and other nomadic empires such as the Kök-Türk (Kwanten, 1979:39), the Karluks (ibid.:59) and the khanate of Chingiz-Khan’s son Chagatai (ibid.:249). The urbanbased Karakhanid state was the first Islamic state in present-day Kyrgyzstan. In the tenth century it had power centres in Talas and Kashkar, and later also in present-day Uzbekistan’s cities of Samarkhand and Buchara (ibid.:61).

However, not all empires that held power over the area can easily be defined as nomadic or settled. A second distinction has therefore been brought forward. The early inhabitants of Kyrgyzstan’s territory are also identified as Iranian, Turkic or otherwise, usually by a reference to their language. As I have mentioned, the early Sakas were said to have spoken an Iranian language. The first Turks appeared on the scene in the sixth century AD. They are referred to as the Kök-Türk (Blue or Celestial Turks). Their khaganate gained momentum in 552, when the last Juan Juan khan was defeated (Mokrynin and Ploskich, 1995:58). Present-day Kyrgyzstan fell under the Western khanate when it split in 581 (ibid., Barthold, 1956:82). The Kök-Türk are remembered by my informants because of their so-called Orkhon Inscriptions. In 1889, a Russian expedition to Mongolia uncovered two monuments to Bilge Khan and his brother Kül Tigin in the valley of the river Orkhon. These monuments were adorned with runic inscriptions that are important to the present-day Kyrgyz because they mention a Kyrgyz people at the Yenisey River. At the Yenisey River itself, similar runic inscriptions have been found.

However, not all empires that held power over the area can easily be defined as nomadic or settled. A second distinction has therefore been brought forward. The early inhabitants of Kyrgyzstan’s territory are also identified as Iranian, Turkic or otherwise, usually by a reference to their language. As I have mentioned, the early Sakas were said to have spoken an Iranian language. The first Turks appeared on the scene in the sixth century AD. They are referred to as the Kök-Türk (Blue or Celestial Turks). Their khaganate gained momentum in 552, when the last Juan Juan khan was defeated (Mokrynin and Ploskich, 1995:58). Present-day Kyrgyzstan fell under the Western khanate when it split in 581 (ibid., Barthold, 1956:82). The Kök-Türk are remembered by my informants because of their so-called Orkhon Inscriptions. In 1889, a Russian expedition to Mongolia uncovered two monuments to Bilge Khan and his brother Kül Tigin in the valley of the river Orkhon. These monuments were adorned with runic inscriptions that are important to the present-day Kyrgyz because they mention a Kyrgyz people at the Yenisey River. At the Yenisey River itself, similar runic inscriptions have been found.

Other Turkic states have been formed by the Seljuk, a branch of the Oguz Turks (Kwanten, 1979:65) and the empire ruled by Timur, also known as Timur-i-leng or Tamerlane (ibid.:266). However, most of the empires that extended their influence over present-day Kyrgyzstan cannot be identified by one clear ethnic background. The Kara-Kitai, for example, are described by Kwanten as the refugee descendants of another empire, the Ch’i-tan empire (ibid.). He explains that scholars still debate whether they were Tungusic, Mongol or Turkic (ibid.:71). In many versions of the Manas epic, the Kara-Kitai are mentioned as Manas’ main enemies (Manas Enstiklopediasy I:276). According to B.M. Yunusaliev, the Kara-Kitai are also known as Kidan in the epic (ibid.), which appears to be the same word as Ch’i-tan. Nowadays, the word Kitai is used for China and the Chinese, but considering the above, care should be taken in identifying Manas’ Kara-Kitai enemies as a group of ethnic Chinese (ibid., see also chapter four). The Kara-Kitai were ousted by the Nayman, another name that occurs in Manas versions, and whose ethnic affiliation is obscure. They were on the run from Mongols, but later referred to as Mongols themselves (Barthold, 1956:106-110). The subsequent Chagatai khanate is described as a loose coalition of Türks, Uighurs, Kara-Kitais, Persians and others under the leadership of a tiny Mongol minority (Kwanten, 1979:250). After Chagatai’s death, the khanate became politically unstable and was ruled by eighteen subsequent khans, until its division in 1338 into Transoxiana and Mogholistan (ibid.:250-251). Most of present-day Kyrgyzstan fell under Mogholistan, Moghol being the word used by the Mongols to denote Turkic peoples (Mokrynin and Ploskich, 1995:135). The previously mentioned Timur, who was born in a Turkic family, came next. When he died, present-day Kyrgyzstan went back to being Mogholistan and was ruled by Mongol leaders who had to deal with Turkic coup attempts (Barthold:146-158). All of this clearly indicates that the population was not reducible to one single ethnic group.

The third recurring element in the description of Kyrgyzstan’s history is the division between North and South. This division, that is so important today, is recovered in past epochs. The situation of the urban Davan in the South versus the nomadic Wu-sun in the North is paralleled in the eighteenth and nineteenth century by the Southern Kyrgyz who were part of the Khanate of Kokhand and the Northern Kyrgyz who fell outside of Khokand and were either independent, or under Russian and Chinese rule.

In the sixteenth century, the occupation of this area was taken up by the Kazakh and the Kyrgyz (ibid.:158). This is where the two story-lines – the history of the territory of Kyrgyzstan and the history of the Kyrgyz people – collide. Before returning to this point, I will summarise the historiography of the Kyrgyz ethnic group.

History of the Kyrgyz

The Kyrgyz are traced back to the third century BC, when Chinese annals speak of a people called the Hehun. Kyrgyzstani scholars argue that these must be the Kyrgyz, because they are also referred to as Hyan-hun, Kigu or Chigu (Mokrynin and Ploskich, 1995:29). These people lived in Southern Siberia, along the River Yenisey (ibid.) or one of its sources in the Altai mountains (Krader, 1962:59), over 1,000 km north-east of presentday Kyrgyzstan. According to Barthold, the Hehun people were not originally Turkic but Samoyedic (ibid.), just like the Uralic peoples who live along the Yenisey River today.

Around the sixth to eighth centuries AD, Greek, Chinese, Arab and Uygur sources mention a Kyrgyz state halfway along the Yenisey River (Mokrynin and Ploskich, 1995:68). According to Mokrynin and Ploskich, the names used in these sources closely resemble the word Kyrgyz. Greek sources speak of Kherkis and Khirkhiz, Arab sources of Khyrgyz or Khyrkhyz, Chinese Syatszyasy or Tszilitszisy, and Uygur and Sogdi texts speak of Kyrgyz (ibid.). However, most of the available information about this group comes from a number of Chinese sources, which use names that can be transliterated in various ways.

Liu speaks of Ki-ku, Chien-k’un or Hsia-ch’a-ssu (Liu, 1958:175), Wittfogel and Chia-Shêng add Ko-k’un, Chieh-ku, Ho-ku and Hoku-ss (Wittfogel and Chia-Shêng, 1949:50). They remark that according to Barthold, these terms are a crude transcriptions by the Chinese of the original word best transcribed as ki-li-ki-si (ibid.). The variety of ethnonyms indicates that the contribution of specific information to the ancestors of the present-day Kyrgyz is problematic, to say the least. Furthermore, there is no conclusive evidence that the people who are called Kyrgyz today are descendants from these ‘Kyrgyz’ in Siberia.

Still, present-day Kyrgyz feel related to these ‘Kyrgyz’, and base their history on secondary information from the Chinese sources. In this interpretation, the Kyrgyz were the people who fought a fierce battle with the Uygurs in 840 AD. The Kyrgyz won and destroyed the Uygur capital Karabalghasun (Barfield, 1989:152-160). They were not interested in trade, and after having turned Orkhon into a backwater they were driven away from it by the Khitans fifty years later (ibid.:165).

In Suji in present-day Mongolia, a text has been found that was written in ‘Kyrgyz letters’ (Mokrynin and Ploskich, 1995:93), a rhunic script similar to the above-mentioned Orkhon Inscriptions. It is dated to the ninth or tenth century and contains eleven verses, the first of which are translated as: ‘I have come from Uygur ground, called Yaklagar-Khan. I am a son of the Kyrgyz.’ (ibid.).

The Kyrgyz are mentioned again in connection to the conquest of a Karluk town in 982. Barthold writes:

At that time the Qirgiz lived in the upper basin of the Yenisey, where, according to Chinese sources, they were visited every three years by Arab caravans carrying silk from Kucha. […] It is possible that the Qirghiz, having allied themselves with the Qarluk, took the field against the Toquz-Oghuz and occupied that part of Semirechyé which is their present home. In any case, the bulk of the Qirghiz migrated into the Semirechyé considerably later. Had they lived in the Semirechyé at the time of the Qarakhanids, they would have been converted to Islam in the tenth or eleventh century. As it is, they were still looked upon as heathen in the sixteenth century (Barthold, 1956:91-92).

In a later work, Barthold cites a manuscript from the tenth century in which the Kyrgyz are located near Kashkar, where they live now. He adds, however, that most of the extant sources, such as the Mahmud al-Kasghari, do not mention them (Barthold, 1962:76).

Barthold maintains that at the time of the Kara-Kita Empire (which in the twelfth century reached from the Yenisey to Talas), the Kyrgyz still lived near the Yenisey River (Barthold, 1956:92). The Kyrgyz were heavily embroiled in the continual warfare that went on until the sixteenth century (ibid.:152-158).

The Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan

During the second half of the fifteenth century, the Kyrgyz moved to the Tien Shan area (Mokrynin and Ploskich, 1995:144-149). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Kyrgyz fought heavy battles against the Kalmaks of Jungaria (also known as Kalmaks, Kalmïks or Oyrats) (ibid.:161-3). These struggles are often seen as the inspiration for the battles in the Manas epic.

In 1757, the Jungarian empire was defeated by the Chinese (ibid.:167). The Kyrgyz now entered into a political relationship with China and had ambassadors in Beijing (ibid.:169). In the 1760s, the Southern Kyrgyz came under the control of the khanate of Kokhand (ibid.:192), one of the three city states (Buchara, Khiva and Kokhand) that ruled Central Asia. However, the Kyrgyz tribes in the North were not conquered before the 1820s, and even then they remained in opposition to the khanate (Prior, 1994:14). In the 1860s, a number of Northern tribes accepted aid from the Russians in their revolts against Kokhand, and managed to break free from it permanently in 1862 (ibid.). According to Prior, ‘the locals went back to nomadizing and farming, and the Russian army continued to pound Kokand’ (ibid.:16).

In spite of this, the Northern tribes were not all at peace, as the Bugu and Sarïbagïsh were at war with one another. In 1854, a fierce battle between the tribes had led to the defeat of the Bugu, even though the manap Urman of the Sarïbagïsh had been killed (Semenov, 1998:73). The Bugu left the shores of Lake Ïssïkköl and went to the Santash region to the East. Here, they became subject to Chinese rule (ibid.).

The Southern Kyrgyz tribes remained linked to Kokhand until the end of the khanate. They fought the Tsarist armies and only fell into Russian hands when Kokhand surrendered in 1876 (Temirkulov, 2004, Prior, 1994:16). A famous name from this era is Kurmanjandatka, vassal to Kokhand and leader of the Southern Kyrgyz since 1862. She was the widow of the murdered Alimbek-datka, and is said to have commanded an army of 10,000 soldiers (jigit). When Kokhand fell, Kurmanjan-datka urged her people to give up their resistance to Russia, and she established good relations with Russian representatives. She retired from public life when her favourite son was executed under accusation of contraband and murdering custom officials. Her role of either heroine or traitor is debated until this day. Nevertheless, her picture adorns the 50 som banknote of independent Kyrgyzstan.

Under the Russian Tsarist administration, present-day Kyrgyzstan fell under various administrative units. The biggest part of the area fell under the Semirechye Province, which was part of the Steppe Governorate from 1882 until 1899, when it became part of the Turkistan Governorate (Murray Matly, 1989:93). From 1891 onwards, waves of Russian colonists came to the Steppe Governorate to settle. After the abolition of serfdom in Russia, landless peasants were attracted by the so-called Virgin Lands of present-day Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. In 1916, revolts of the Muslim population against the Russians broke out all over Central Asia (Carrère d’Encausse, 1989:210-211). The direct cause was a decree that mobilised the Central Asians into workers’ battalions to replace Russian workers who fought in the first world war. Relations with Russian settlers had been tense, especially amongst the Kyrgyz of Semirechye, and as a result the revolt was fierce (ibid.). In Semirechye, 2,000 Russian settlers were killed, but far more locals perished. One third of the Kyrgyz population fled to China (ibid.).

The Soviet Union

The Socialist Revolution of 1917 was largely a Russian concern in Semirechye. According to Daniel Prior, the general Kyrgyz population did not take active part in the revolution (Prior, 1994:29). A number of educated young men took the opportunity to make a political career within the new communist structure, which sustained an active policy of indigenisation, or as Terry Martin terms it: affirmative action (Martin, 2001). By the end of the 1930s, all of them had perished in the purges. In the years of civil war (1917-1920), famine ruled daily life in Central Asia (Brill Ollcot, 1987:149-152). After the civil war, once Soviet rule was firmly established, the construction of a socialist society began.

Martha Brill Olcott speaks of the Kazakhs when she writes: those who could afford it migrated part of the year and stalled their animals in winter, while those who could not support themselves solely through livestock breeding practiced subsistence farming as well. […] Clan, village, and aul authorities simply reconstituted themselves as soviets (ibid.:162).

During the years of the New Economic Policy, the economy gradually recovered.However, in 1929, a programme of collectivisation was initiated which caused another horrendous famine. People preferred to slaughter their animals rather than see them becoming communal property, even though each household was allowed to keep a few animals (ibid.:176-187). This did not prevent collectivisation to be implemented and becoming the basis for the economy for the following sixty years.

Another restructuring process of the first Soviet years is known as the national demarcation. The former Tsarist empire was radically reorganised on the basis of national autonomy. A number of ethnic groups were recognised as nations and were awarded republics or autonomous regions. The Kyrgyz were among them, and by 1936, the Kyrgyz SSR became one of eleven (later: fifteen) Soviet Socialist Republics (SSR). The status of SSR proved most important in 1991, when all fifteen SSR became independent states, in contrast to areas such as Chechnya, Dagestan and Tuva, which remained under Moscow’s control as autonomous republics within the Russian Federation.

By the time collectivisation and national demarcation had been completed, the Purges began. In 1934, the first wave of purges swept over the Soviet Union. ‘Bourgeois nationalism’ was regarded as the evil that needed to be eradicated. The second wave in 1937 was even more lethal, and many Central Asian leaders were executed. The second world war, known as the Great Patriotic War in the USSR, left deep traces in Kyrgyzstan. Every village has a monument for the sons that fell in battles far away. By this time, the policy of indigenisation had shifted towards a Russian-oriented governance. Teresa Rakowska-Harmstone explains:

Local nationals were required to occupy the highest hierarchical positions and all posts of representative character. Invariably, however, a local leader was either seconded by a Russian or backed by a Russian or Russians close to him in the hierarchy. […] The lower executives were almost always Russians, especially in the central Party and state agencies. While not in the public eye, they actually formed the backbone of the republican bureaucracy (Rakowska-Harmstone, 1970:96).

The death of Stalin in 1953 was lamented all over the Soviet Union. The statues and pictures of Stalin remained in place until Krushchev’s famous ‘secret speech’ of 1956, in which he denounced the personality cult surrounding Stalin and accused him of crimes committed during the purges. But even today, many people in Kyrgyzstan speak highly of Stalin, praising his strong leadership and recognition of national culture and downplaying the scare of the purges.

The stretch of time between the end of the second world war and the beginning of perestroika in Central Asia is often characterised as the period of stagnation (Prior, 1994:38-41). Most historic overviews brush over these forty years as if nothing much happened. Politically, the scene was dominated by conservative party secretaries who stayed put in their positions for decades. In the Kyrgyz SSR, Turdakun Usubaliev was First Secretary from 1961 until 1985. In the areas of industry, agriculture, education, health care, infrastructure and culture, however, massive achievements were accomplished. Contrary to the image of the Soviet Union as a hated, totalitarian regime, the people I met in Kyrgyzstan looked back upon the Soviet period as a prosperous and pleasant era. Although they did appreciate the openness of the new times, they were not particularly relieved that the Soviet Union was over. The people I encountered had found means to get by and function within the framework of state socialism.

In November 2007, a news report on Dutch television drew parallels between the present NATO presence in Afghanistan and the Soviet Afghan war of the 1980s. An interviewed Russian general concluded: We should never have tried to implement socialism in Afghanistan. It never gained foothold, just as it failed in Mongolia and Uzbekistan and Kirgizia.

From my perspective, this seems a misinterpretation of the influence of socialism in Kyrgyzstan. In the life stories of my informants, socialism was deeply integrated into their social world. Their economic activities took place in socialist collectives, socialist world views were taught at schools and accepted by the pupils, children were active in organisations such as the Komsomol (Communist Youth Union), arts were celebrated in festivals with a socialist tinge, and so forth. The stereotypical image of a socialist state that forced itself upon the people, who kept their true convictions and expressions secret, also seems false in the light of what my informants told me. My host father in Kazïbek village, for instance, was a fervent Muslim and socialist at the same time, and he saw no contradiction in that. I do not know if he would have expressed his adherence as vehemently during Soviet days; perhaps the demise of socialism had created room for a new assertion of his Muslim identity. However, he was so at ease with the combination of the two convictions that I deem it likely that this was not new for him. In a similar way, Manaschï Talantaalï Bakchiev had combined becoming a Manaschï with active socialist networking. He told me he had been an active and ambitious member of his local Komsomol department in his teenage years. These were also the years when he began to explore his Manaschïhood.

In 1987, as the perestroika and glasnost policies gave room for critical thought and discussions, a few debating clubs consisting mainly of young Russian-speaking intellectuals arose in Frunze (Babak, 2003) . By 1989, these political clubs had ceased to exist, partly because of harassment by the authorities, and partly because their position was taken over by groups that united over certain issues, such as ecology or culture (ibid.). In this climate, a political action group called Ashar became popular because of its standpoint on housing issues. There was a growing shortage of housing in the capital, and when young Kyrgyz people started to move to the city they built illegal dwellings outside and inside the city centre (Rashid, 1994:146). A group of young Kyrgyz intellectuals formed Ashar (litt: mutual help, solidarity) and managed to obtain land from the city authorities for legal home building (ibid.).

A few months later, in June 1990, riots broke out in Osh oblast. These evolved into a week of extremely violent clashes between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz in the area between Osh city and Özgön. According to official numbers, 120 Uzbeks, 50 Kyrgyz and one Russian were killed and over 5,000 crimes such as rape, assault and pillage were committed (Tishkov 1995:134,135). As with any violent conflict, opinions on the culpability and the causes of the conflict vary enormously. In his study ‘Don’t kill me, I’m a Kyrgyz!’, Tishkov points to a wide range of factors that led individuals to commit their atrocities.

Poor living and health conditions and rivalry over land between the ethnic groups were structural causes. At the heat of the moment, fury seemed to be fuelled by rumours of Uzbeks killing Kyrgyz, by strong individuals who stirred up the youth, the absence of authoritative peace keeping and by alcoholic intoxication. Tishkov names another element of the frenzy of that week, which is of specific interest for this study: Young Kyrgyz on horseback were trying to demonstrate their strength and superiority by lifting up an opponent by his legs and smashing him down on the ground – exactly in the way the legendary Kyrgyz heroes supposedly overpowered their enemies. ‘We have read about it a lot, but this is the first time it’s been possible to try it out for ourselves!’, they said (Tishkov, 1995:148).

The unrest of the housing and the Osh riots led to the dismissing of First Secretary Absamat Masaliyev. When none of three candidates managed to get a majority vote from the Kyrgyz SSR Supreme Soviet, Askar Akayev came into the picture, and after winning the vote he was installed as President. Akayev is often portrayed as the first non-Communist president of Central Asia. This is true to the extent that he was not on the top list of Communist leaders at the time of his election by the Kyrgyz SSR Supreme Soviet. His career was in mathematics and physics, and in 1989 he became the president of the Kyrgyz Academy of Sciences. However, Akayev did also have a political career within the Communist Party. In his 1999 biography Askar Akaev, the First President of the Kyrgyz Republic, his position of Head of the Department of Science and Higher Educational Institutions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party in 1986 is boasted, as well as his election as Deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and his positions of member of the USSR Chamber of Nationalities and the Supreme Soviet Committee on Economic Reform in 1989 (Rud, 1999:21,23). Be that as it may, Akayev was an unexpected face at the head of the Kyrgyz SSR, and he brought with him an atmosphere of change and reform.

After the Soviet Union

Less than a year after Akayev’s installation as president, conservative communists in Moscow staged a coup d’état against Gorbachov’s government. Akayev was the only Central Asian leader who immediately condemned the coup. A few days later, the fifteen republics of the Soviet Union had all declared their independence, and the Soviet Union ceased to exist. His early denouncement of the coup gave Akayev the aura of a brave, strong and democracy-loving leader in the eyes of western observers. This was important, as Akayev took the standpoint that Kyrgyzstan, with very few natural resources of its own, was dependent on the outside world for economic security. The Kyrgyz government put enormous effort into building up good international relations, looking in many directions.

Western countries were charmed by his interest in economic reform and democracy. Japan was honoured by becoming the model for Kyrgyzstan’s road to development as was Switzerland, South Korea and Turkey. Turkey was especially enthusiastic as it looked forward to forging alliances with the new Turkic republics. Ties with Russia had loosened rapidly, but Akayev went at great lengths to keep good relations with Russia. Border disputes with China originating in Soviet times were resolved as quickly as possible and trade opened up immediately. Canada provided a gold mining company that in a joint venture with the Kyrgyz state started the exploitation the Kumtor goldmine.

The biggest sums of money obtained from diplomacy were the loans by the IMF and the World Bank. The introduction of shock therapy led to quick reforms of the economy, but did indeed leave the population in a state of shock. Over time, the position and power of the president changed, both in relation to the parliament (Jogorku Kengesh, litt: Supreme Soviet) and the population. As Akayev heeded the parliament less and less, most of the population started to regard him as a corrupt leader who enriched himself and his family, and who had proved unable to secure a strong international position for Kyrgyzstan. The presidential elections of 2000 also made international organisations such as the OSCE critical of Akayev, and when at the 2005 parliamentary elections the attempts at manipulation cropped up again, Akayev had fallen out of grace by almost everyone. The elections were followed by protest marches. To the surprise of many, these led to a true velvet revolution, known as the Tulip Revolution. President Akayev was ousted and escaped to Moscow.

A new era started with Kurmanbek Bakiyev as president and Felix Kulov as prime minister. Bakiyev and Kulov started off as political rivals for the presidential elections. Their campaigns increased precarious tensions in the country, because Southerner Bakiyev and Northerner Kulov both capitalised on long-standing antagonism between the North and the South. The escalations came to a halt when the two opponents proclaimed their unexpected alliance: if Bakiyev was chosen as president, Kulov would be his prime minister. This is what happened, but the tensions between North and South did not diminish. In 2007, a Kyrgyz informant wrote to me in an email that ‘we have a big North-South problem at the moment, an invisible war is going on’.

The new government renewed ties with Russia, allowing Russia to intensify its influence in economic and military spheres. In October 2005, the murder of two parliamentarians, who were also well-known businessmen, gave much unrest within the government and led to a sense of disappointment with most of the population in their new leadership. People felt unsafe, and rumours about criminal infiltration of the government became louder. The Tulip revolution had turned into disillusionment very quickly. Bakiyev faced numerous street protests against him, mostly on the issue of the promised new constitution that would transfer some of the president’s powers to the parliament. In April 2007, Bakiyev finally signed amendments to the constitution that would diminish presidential powers. Five months later, however, the new constitution was invalidated by the Constitutional Court of Kyrgyzstan. In response, Bakiyev called a referendum to be held in October, at which the new constitution was approved by over 75% of the votes. The referendum was heavily criticised by Kyrgyzstani and international organisations. Bakiyev then called early parliamentary elections in December 2007. With the help of new rules that made it exceptionally difficult for parties to pass the two established thresholds, these elections were won by Bakiyev’s newly formed Ak Jol party, who thus gained control over the new parliament.

Economy

In the late nineteenth century, the Kyrgyz practised transhumance animal husbandry. Their livestock consisted of the ‘four cattle’ (tört tülük mal): camels, horses, sheep-goats and cows. Radloff adds that they herded yaks too (Radloff, 1893:527). My informants claimed that before the revolution, the Kyrgyz diet was made up mostly of meat and diary products. However, Radloff reports that the Kyrgyz (Kara-Kyrgyz) practised agriculture on a wider scale than the Kazakhs (Kasak-Kyrgyz) (ibid.:528). According to Radloff, they grew wheat, barley and millet, for which they used a carefully maintained system of artificial irrigation (ibid.).

Shahrani notes of the Pamir Kyrgyz, a group of Kyrgyz who fled the communist regimes in the Soviet Union and China, that hunting and collecting were marginal economic activities in the 1970s (Shahrani, 1979:108). It seems likely that the same counted for the pre-revolutionary Tien-Shan Kyrgyz. Radloff writes that the Kara-Kyrgyz only practised hunt for amusement (Radloff, 1893:528). In the time of my fieldwork, my informants mentioned ibex (gig) hunts, and I saw many fox and wolf skins decorating the walls. Still, hunting does not appear to have been vital for survival. Collecting of berries, herbs and wild onions was practised during my field research, and presented by my informants as part of the Kyrgyz way of life. Goods such as tea and guns were purchased through trade with settled peoples. Semenov, who travelled in Kyrgyz lands in 1856-1857, tells that the tomb of a hero named Nogay was built by craftsmen from Kashkar, for which his family paid two iamby of silver, two camels, five horses and three hundred sheep (Semenov, 1998:167).

Shahrani describes how the Pamir Kyrgyz traded their animal products for grain from their agricultural neighbours, or directly through itinerant traders (Shahrani, 1979:110). The traders very often cheated the Kyrgyz by asking high prices or never coming back for payments. The nineteenth-century Tien-Shan Kyrgyz had an additional way of purchasing goods: they raided merchant caravans. Explorer Semenov Tien-Shanski mentions an encounter with a group of ‘Karakirgiz bandits’ of the Sarïbagïsh clan who were pillaging a small Uzbek caravan, which was going to Vernoe (presently Almatï) (Semenov, 1998:92).

In summer, the people and their livestock lived in mountain pastures up in the mountains. In winter, they moved down to lower fields where temperatures were higher. The people lived in round tents they called boz-üy (grey house, depending on the colour they could be called ak-üy (white house) or kara-üy (black house) as well) in Kyrgyz. In English, these tents are called yurts, an adaptation of the Russian word yurta. The following information about yurts was provided by my informants, based on present-day habits that they regarded as unaltered since time immemorial. The frame of the tents is made of fir wood, the cloth of thick felt. The tents are warm and comfortable and large enough for families to stand, eat, cook and sleep in. They are easily taken down and transported to the next camp site. The lay-out of the yurt is subject to a number of rules and traditions; the right side is for the women (epchi jak), the left side for the men (er jak) and the place opposite the door, the tör, is the place where the most respected guests are seated.

The fireplace is in the middle so that smoke can get out through a hole in the roof (tündük, now the symbol on the Kyrgyz flag). Decorations play an important part in the interior of the yurt. Usually, there is a decorated chest used to store things in and on, the walls of the yurta are adorned with patterns made of coloured wool curled around reeds, and the felt carpets on the floor are made in various designs. The carpet called shïrdak is made of a patchwork of coloured felt and the ala-kiyiz carpet has the design worked into the carpet during the felting process. Designs are usually abstract forms that resemble the French lily, representing a magic bird.

Wealth was not equally distributed among the nineteenth-century Kyrgyz. Radloff compares the wealth of the Kyrgyz to that of the Kazakh, and implies the existence of the category ‘rich’:

In general it can be said that the black Kirgis {Kyrgyz] own less cattle than the Kirgis of the Great Horde [Kazakh]. People who have 2000 horses and 3000 sheep already count as extraordinarily rich (Radloff, 1893:527).

In the travel journal of Semenov, we read that he has encountered both impoverished and wealthy Kyrgyz. The poor Kyrgyz were often deprived due to the war between the Bugu and Sarïbagïsh clans. Once, Semenov and his group met a group of captives from the Bugu clan who had been abandoned by their Sarïbagïsh capturers. They were: … dragging themselves along, hungry, emaciated and half-clothed, so that we had to share our food with them, in order that they should not starve to death (Semenov, 1998:149).

The wealth of the clan leaders where he stayed as a guest was not so lavish that he spent any words on it. He was more interested in the appearance and character of the people he met than in their wealth and possessions. Semenov does write that when he tried to befriend Umbet-Ala, the manap of the Sarïbagïsh clan, to secure a safe passage through the Tien-Shan, the manap reciprocated his gifts with three excellent horses (ibid.:97). This transaction proved to be successful and Semenov did indeed travel the Tien Shan safely. It is not unlikely that traders for whom the Tien Shan was a part of their trading route engaged in similar contracts with the leaders of Kyrgyz clans. For these agreements to work, it was vital that the leaders exerted a degree of control over their subjects. The case of Semenov’s agreement suggests that Umbet-Ala did have the necessary amount of authority. Previous to the agreement, Semenov and his party feared the Sarïbagïsh and avoided them where they could. Later, the bond of friendship (called tamyr by Semenov) with Umbet-Ala even helped Semenov to persuade the Sarïbagïsh to let go their Bugu captives (ibid.:179).

In the Soviet period, Kyrgyz pre-revolutionary society was typified as feudal, which made the richer Kyrgyz into feudal lords who extorted their serfs and slaves. This image can be nuanced, however, if we remember that wealth was counted in livestock – a highly perishable good in the harsh mountain climate. The richer Kyrgyz were therefore highly dependent on the poorer for their labour to keep the livestock intact and flourishing.

Shahrani explains that among the Pamir Kyrgyz in the 1970s: … this stratification has not caused any serious confrontation or conflict between the very rich and the very poor. On the contrary, the existing ties of kinship, friendship, and affinity in many cases have been strengthened through herding arrangements between rich and poor relations, while new ties based on economic interdependence have developed (Shahrani, 1979:182).

It seems likely that among the nineteenth-century Tien Shan Kyrgyz, a similar mechanism was at work. One informant said to me that there were rich people among the Kyrgyz, but it depended on the person himself. Whether you were rich or not was determined by what kind of person you were. On the other hand, he also knew of the existence of slavery among the Kyrgyz, and assumed that people were slaves by birth, for the suffix -kul in personal names indicated their status as slaves.

The main basis for Kyrgyzstan’s economy is still animal husbandry. Transhumance is still part of the herding technique, but nowadays it is not the entire clan or village that moves to the summer pastures. Most people remain in the village, and a number of shepherds take the livestock into the mountain pastures (jailoo). Next to herding, the cultivation of vegetables, fruit, nuts, cotton, hemp and tobacco is an important source of income. A large part of the industry is made up of agro processing and mining. Kyrgyzstan has a number of gold, coal, uranium and other mineral mines. Most of the mining sector has declined dramatically since independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. The exception is formed by gold mining, which attracted foreign investment. The Canadian Cameco gold mining company obtained a 33% interest in an agreement with the Kyrgyz state company Kyrgyzaltïn to exploit the Kumtor goldmine in the Tien Shan range, south of Lake Ïssïkköl.

The government remains an important source of employment. The informal economy is another important pillar of Kyrgyzstan’s economy, accounting for almost 40% of the GNP in 2000, mostly in street vending (Schneider, 2002). Kyrgyzstan very rapidly became a poor country when the infrastructure of the Soviet Union suddenly collapsed. Collective farms and factories were no longer supplied with fuel and other raw materials and the market structure fell apart. The government under president Akayev opted to apply the so-called ‘shock therapy’ method for economic reform that was promoted by the IMF and the World Bank (Abazov, 1999). Shock therapy has as its main goal a quick implementation of economic reform, in a concentrated period of less than two years, with a focus on reaching a macroeconomic equilibrium. In Kyrgyzstan, this meant that the system of central planning and state-controlled prices and subsidies was abandoned. State property such as houses, factories and land was privatised. Although after a free-fall of six years the economy did indeed show signs of recovery in terms of GDP, the effects on the standard of living for most of the population was negative, according to Abazov, a Kyrgyzstani political scientist at the Columbia University (ibid.). He explains that the Soviet state had used overstaffing as a means to hide unemployment, and had used price control to maintain a good standard of living.

When this state-controlled system was abandoned so quickly, unemployment, economic passivity and poverty were the immediate results. Next to this, as Abakov puts it:

Withdrawal of the state from playing an active role in economic development and maintaining law and order led to the growth of the so-called ‘robber-capitalism’ and created a chaotic business environment (Abakov, 1999).

Many of my informants spoke approvingly of Uzbekistan, that had rejected the shock therapy, and wished that Kyrgyzstan’s government had chosen a similar route of gradual and controlled reform. Outside observers may find it difficult to estimate the true extent of poverty in Kyrgyzstan. A Dutch OSCE election observer who had stayed in Naryn for three months for the 2000 parliament elections asserted to me that there was hardly any poverty in Kyrgyzstan. Everywhere she went, the table was loaded with food. She seemed not to realise that the rules of Kyrgyz hospitality require an excess of food, and that people had probably drawn on their entire social network to feed their esteemed foreign guests properly. It was not until my second year in Kyrgyzstan that I began to witness glimpses of the true effects of the crumbling economy. One day, a befriended couple confided that they did not have any money left to buy food. It was days away until the husband’s salary was expected, but the cupboards were empty. I gave them some money and stayed home to baby-sit for the two children. When my friends came home from the market with a bag of flour and some sugar, the children burst into singing and dancing in a way I had not even seen Dutch children rejoice over a beautiful birthday cake.

A factor that makes poverty hard to deal with for most Kyrgyz is the shrill contrast with the relative wealth and security they had experienced in the Soviet era. Basic needs such as bread, health care and education, but also pleasures such as an evening at the cinema and eating ice cream had been available to everyone. Now, daily life has turned bleak and a struggle to survive. In the late 1990s, the time of my fieldwork, people often mentioned the loss of simple pleasures. For villagers, it was no longer enjoyable to go to Bishkek, because the attractions of the city had become unaffordable. One day when my German friend and I were laughing out loud, a Kyrgyz old man sighed: ‘Such a long time ago that our Kyrgyz girls could laugh like this!’

The increase in prices, inflation and loss of sources of income has fuelled corruption. Those who maintained a position with relative power often find only one way to make ends meet: capitalise on that power in a downward direction. A policeman or a school teacher who does not receive enough wages from the government will extract money from those who depend on him or her. This way, the burden for public services falls on the very poor rather than being shared through a tax system. Generally, however, there is a lot of tolerance for this petty corruption. If people do not make enough money to live on, what are they to do? The corruption of high government officials who put foreign loans into the refurbishment of their luxury homes is mostly regarded with resignation – it is seen as annoying and offensive, but that is what the rich do. In 2005, this resignation quite unexpectedly turned into action when the president was ousted. Unfortunately, nothing seems to have changed with regard to corruption. The system of all-pervasive corruption and nepotism paralyses many people in their personal initiative and upward mobility. On the other hand, this system also provides social survival and advancement in Kyrgyzstan. It may not be easy to find one’s way in this web of dependency, but it is the game one has to play.

Social Organisation of the Kyrgyz: Family Structure and Politics

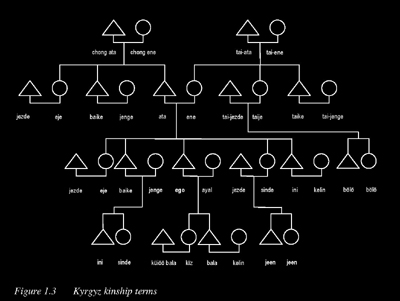

At the time of my fieldwork, the Kyrgyz traced their descent patrilineally. Surnames are based on a person’s father, in that a person inherits either their father’s surname (for instance, president Akayev’s son is called Aidar Akayev and his daughter Bermet Akayeva), or their surname becomes the first name of the father followed by uulu (his son) or kïzï (his daughter) (for example the son of one of my Manaschï informants, whose name is Kazat Taalantaalï Uulu). Furthermore, descent is based on knowing one’s seven fathers (jeti ata), that is the patrilineage up to the seventh generation. In enumerations of a person’s seven fathers, the seventh father is often primal father. An informant once listed his seven fathers for me, with the name of his seventh father coinciding with the name of his family’s sub-clan. When I asked what the seventh father of his son was, he became slightly confused and was not sure whether he should skip a father or make the sub-clan’s name the eighth father of his son. Every Kyrgyz person is supposed to know his or her seven fathers, first of all because it is proof of being ‘a good Kyrgyz’, and secondly it is needed to maintain a marriage taboo. The Kyrgyz consider marriages between people from the same fathers up to the seventh generation out of bounds. Marriage with a person from one’s mother’s line is allowed, even if he or she is a first cousin. A number of informants told me that this is because ‘blood goes through the father’. Although the family of a daughter-in-law (kelin), the kuda, are treated with high respect, children belong to the family of the father and should stay there in case of separation or death of the mother.

The Kyrgyz observe patrilocality: generally, the bride moves to the household of her husband’s parents after (or during) the wedding. After a few years they may move out to a home of their own. Ideally, the youngest son and his family never move out but remain in the house of their parents, taking care of them in old age.

The Kyrgyz observe patrilocality: generally, the bride moves to the household of her husband’s parents after (or during) the wedding. After a few years they may move out to a home of their own. Ideally, the youngest son and his family never move out but remain in the house of their parents, taking care of them in old age.

Figure 1.3 presents a genealogy of Kyrgyz kinship terms as I found them in the village Kazïbek in the province Narïn. Most noticeable is that terms for relatives on the father’s side differ entirely from the terms for relatives on the mother’s side. Furthermore, relative’s age is a distinguishing factor: one’s older sister is addressed with a different term than one’s younger sister. People address one another by their first names followed with the appropriate kinship term – whether they are actual kin or not. Implicit in these terms is a high respect for older generations. This carries far: older siblings are addressed with the polite sïz (you) instead of the informal sen (you). I encountered a number of situations where an older brother had demanded to adopt a younger brother’s child when he remained childless himself. Family relations that were out of the ordinary, such as adopted children, second wives, or illegitimate children were a source of shame and embarrassment, and not openly spoken of. However, after staying with a family for a number of weeks, I was often told – in a low voice – about the true nature of relationships.

Political leadership among the Kyrgyz was traditionally family and clan based. Ideas on leadership among the nineteenth-century Kyrgyz has been subject to the Soviet political tunnel view, which made the term bi-manap stand for a group of despotic tyrants. Saul Abramzon, a Soviet historian and ethnographer, wrote that at the end of the nineteenth century, the Kyrgyz already had a society with patriarchal-feudal characteristics (Ambramzon, 1971:155). He explains:

Before the Great October Revolution, the mass of the Kyrgyz population owned comparatively small herds. At the head of certain groups of the population stood feudal-tribal nobles personified by bis and manaps. The exploitation of the workers by manaps and bis occurred in the framework of the penetration of social life with the ideology of ‘tribal unity’ and ‘tribal solidarity’ which found its expression in many forms of the patriarchal-tribal mode of life (ibid.:157).

The ideas of exploitation and despotism of the bis and manaps may not have come totally out of the blue, for Radloff reported that: The division of lineages is entirely as among the Kasak-Kyrgyz. In stead of Sultans, however, they had lords elected from the black [i.e. ordinary] people, that they called Manap. The Manaps, I was told, had exerted almost despotic authority over their subjects (Radloff, 1893:533).

Daniel Prior describes the situation as follows: There is no doubt that the institution of manaps was brought on in part by the fragmented Kirghiz tribes’ craving for security, yet the tyrannical power of these chieftains amounted to despotism and became an extra burden on the population. There was much to bear in their lot: while attempting to live as they were being squeezed politically, militarily, and economically by Kokand, China, the Kazakhs, and later Russia, most tribes existed in a state of constant movement and readiness for battle (Prior, 2002:50).

Semenov, however, only mentions one instance of a despotic ruler, namely Vali-khan of Kashkar, saying that he was noted for great brutality (Semenov, 1998:197). Shahrani describes an entirely different version of leadership among the Pamir Kyrgyz in the 1970s. Of course, it is impossible to extrapolate their society directly to the nineteenth-century Tien-Shan Kyrgyz. Although the Pamir Kyrgyz faced a lot less interference from a larger state than the Tien-Shan Kyrgyz, their permanent migration to the high summer pastures of the Pamirs, as well as the loss of ties with the other Kyrgyz groups, must have had an impact on the political sphere as well. However, their case does bring into light a different possible political organisation among the Kyrgyz, which opens the mind to new readings of the role of nineteenth-century leaders. Furthermore, Shahrani’s descriptions of leadership coincides strongly with the position of elders (aksakal) and heads of the family during my fieldwork, although these had a less clear political position vis-à-vis the state of Kyrgyzstan.

The Pamir Kyrgyz were headed by a khan in the 1970s. The term khan was known in the Tien Shan in the nineteenth century, but it was hardly ever used for (or by) a Kyrgyz leader17. The headmen of different clans (uruu) were called manap. Other titles for public functions were bek (a military rank) and bi (judge). The dispersion of the various Kyrgyz clans under different states (Khokand, China, Russia) probably prevented the rise of a single khan. The Pamir Kyrgyz, in their isolation from a larger state, had located the upper authority amongst themselves. Shahrani describes three layers of leadership: the headman of a camp (qorow) is called a be, the headman of a clan (oruq) is an aqsaqal, and the khan heads all of them (Shahrani, 1979:164). Of the aqsaqal (litt: white beard), Shahrani writes:

The aqsaqal is expected to be a man over forty years of age, known for his impartiality and good judgement. The position is not elective or hereditary. Rather a man is acknowledged by the members of a group as they turn to him for help, advice, or the mediation of conflicts. Therefore, the position is attained through public approval and maintained as long as such consent continues without public challenge from another member. The aqsaqal is treated in public gatherings with such special attention as seating him in the place of honor. He acts as the spokesman for his group in all matters of public or private concern, and represents the interests of his membership to the khan, and through him to the local government (ibid.:156).

Shahrani does not elaborate on the position of the camp elder (be). About the khan he says the following: The office of the khan is the single vehicle through which the unity of the Kirghiz community is achieved. (…) The rank of khan is nonhereditary in principle nor is it elective or ascribed. Instead, it is generally assumed by the most obvious candidate, usually the aqsaqal of one large and powerful oruq, and is legitimated through public consent by the Kirghiz and/or recognized by external forces – local government authorities or outsiders such as the neighbouring Wakhi, traders, visitors, and so forth. (…) strong and effective leadership qualities in Kirghiz society entail bravery (military prowess in the past), honesty, abilities in public persuasion and oratory, sound judgement, being a good Muslim, membership in a large oruq, and of course success as a herdsman, with a large flock and wealth in other tangible goods. (…) what is important in this instance is not the possession of goods and animals, but how they are used to help the community. Hospitality, generosity, and the offer of help to one’s relatives and to the needy and poor, stand out as the signs of being a good Muslim and are personal qualities desired among the politically ambitious in Kirghiz society. (…) His role is very often reconciliatory and mediational (…) He does not have a police force and does not bring individuals to trial (ibid.:164, 165).

If we compare the ethnographic study of Shahrani with what we know of the nineteenthcentury Kyrgyz, we find that first of all, the leaders of the different clans played a central role in the reception of guests. Valikhanov, Semenov and Radloff were all fed, entertained and given a place to sleep in the households of the chiefs. Semenov mentions a night spent at the camp of the nobles of the Bugu of Boronbai’s clan. They were received by Baldïsan, a Bugu of ‘blue blood’, who was ‘peace-loving by nature’, did not participate in the bloody strife, never went on a raid, but busied himself with music (he played the dombra) and listening to ‘the songs of folk-tale narrators and improvisers’ (Semenov, 1998:181). The night that Semenov stayed at his camp, Baldïsan played the dombra for him and called on the bards to recite poetry for his guests.

Semenov also elaborates extendedly on the war between the Sarïbagïsh and the Bugu that was in full swing during his travels in the Tien Shan. He assigns an important role to the leaders (manap) in these wars by focussing his descriptions of the motives and effects of the war on the leaders personally. He speaks of the leaders as if they singlehandedly decide on the fate of their subjects, as in the following passage: One of the powerful Bogintsy [Bugu] clans, the Kydyk, led by Biy Samkala, and bearing the same relationship to Burambai [Boronbai] as the appanage princes did to the grand princes in ancient Russia, had quarrelled with the chief Bogintsy manap and having detached himself from him, decided to move with his whole clan, numbering 3,000 men capable of carrying weapons, beyond the Tian’-Shan’, across the Zauka Pass. The Sarybagysh, who already occupied the whole southern littoral of Issyk-kul’ (Terskei), insidiously let the rebellious Kydyk go through to the Zauka Pass, but when the latter with all their flocks and herds were ascending the pass, they attacked from both sides (…) and completely routed them. (…)

However, old Burambai grieved not so much for the losses of the Kydyk, who had wilfully defected from him, as for the loss of all his territory in the Issyk-kul’ basin, of his arable land and small orchards on the river Zauka and for the female captives of his family (ibid.:145).

Whether this view on the position of the leaders as all-powerful reflects the actual situation, or whether Semenov projected an ethnocentric view on the Kyrgyz, remains a question.

There appears to have been a certain sense of unity among the different Kyrgyz clans in the nineteenth century. Russian observers speak of the Kara-Kyrgyz or the Dikokamennye-Kyrgyz as distinct from the Kasak-Kyrgyz. It is unclear what the basis of this distinction was, however. There appears to have been no political form for unity or federation in the nineteenth century. At some point, the different clans that are known as Kyrgyz today even fell under three different states: the Southern Kyrgyz were ruled by the khanate of Khokand, most Northern clans were subjected to Russia and the Solto fell under Chinese rule. Two of the Northern clans, the Bugu and Sarïbagïsh, were involved in a bloody feud. Still, they are presented as one group by outsider contemporaries and presentday historians.

The clan structure appears to have been fluid and flexible. Although according to legend, the name Kyrgyz may have come from ‘kïrk ïz’, meaning forty clans, there is no conclusive enumeration of precisely forty clans. Kyrgyz genealogists (sanjïrachï) provide very detailed family trees, but none are the same. Sub-divisions of clans can become important units in their own right, others lose their importance over time. Although there is a distinction between ulut (people, the Kyrgyz), uruu (clan, e.g. Bugu, Cherik) and uruk (sub-clan, e.g. Sarï-Kalpak, Akchubak), these divisions are not as clear-cut as the terminology suggests.

It seems likely that clan membership was patrilineal in the nineteenth century, as it is today. However, Daniel Prior quotes G. Zagriazhskii, ‘an observer in 1873’, who gives an entirely different account of clan membership: The membership of a Kirghiz to one tribe or another is not permanent and unchanged. One of them has merely to move from the Sarïbagïsh lands to the Solto, and he will not be called a Sarïbagïsh, he becomes a Solto. Moving to the Sayaks, he becomes a Sayak […], but this may only be said of the common people, the bukhara […] Manaps preserve the division into tribes, and strictly maintain them (Zagriazhskii in Prior, 2002:70).

It has become fashionable to describe contemporary Kyrgyz politics as tribal, with clan members favouring each other. A joke I heard on a bus, told by a Kyrgyz passenger, makes clear that region overrules clan in this respect: A bus driver walks up to a passenger and asks him: ‘Are you from Kemin?’ (Kemin is the birth place of Akayev)? The passengers replies: ‘No.’ ‘Are you from Talas, then?’ (Talas is the birth place of Akayev’s wife) The passengers replies: ‘No.’ ‘Then take your feet off the chair!’

Ethnicity, religion and language

Three important markers that characterise a country are ethnic composition, religion and languages of the population. These markers are especially strong because they link up easily to global images and patterns in an individual’s world view. Islam in Kyrgyzstan will be linked to Islam in one’s home country, the Islamic states in the Middle-East and nowadays almost inescapably to Islamic fundamentalism and terrorism. The ratio of ethnic groups and its meaning for ethnic relations will be compared to those at home and elsewhere and fit into one’s understanding of global settlement and migration patterns.

Knowing what languages are spoken falls into the jigsaw image of the languages of the world and their attached ethnic affiliations. However, Kyrgyzstan, together with the other post-Soviet countries, has a particular history in these three aspects that need to be kept in mind if one wishes to understand the meaning of ethnicity, religion and language for the people who live in Kyrgyzstan. For the purpose of introduction, a general overview will suffice.

Ethnicity

At the end of the Soviet era, the Kyrgyz republic proudly claimed to house more than eighty ethnic groups, or ‘nationalities’. In Soviet terminology, the Kyrgyz were the titular nation of the Kyrgyz SSR, meaning that they were the name-giving ethnic group of the republic. Political power was reduced to a minimum, as well as the sense of ownership of the republic. The right of all nations for self-determination was an important communist slogan, but it was placed second to the socialist project. This led to a dynamic of different freedoms and restrictions at different times. The Kyrgyz SSR was inhabited by people from many other ethnic groups, most notably Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Kazakh, Tajik and Russian. These groups already inhabited the territory at the time of the border demarcation. Over time, more people from all over the Soviet Union settled there, some out of free choice, some with forced migration as punishment and some professionals such as doctors and teachers who were sent to peripheral areas to perform socialist duties. The Kyrgyz SSR, like the other soviet republics, was proud to house over eighty nationalities.

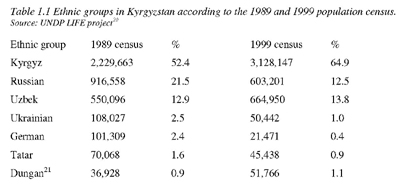

In the years since independence, there has been a significant shift in the ethnic make-up of the country. Most notable is the halving of the percentage of Russian inhabitants. The rapid decline of economic and emotional security led Russians, Germans and Jews to move ‘back’ to Russia, Germany or Israel. Apart from these push factors, there were pull factors for the migrants as well. The governments of Germany and Israel offered preferential access to their ‘compatriots’ from the former Soviet Union, who were regarded as finally having the chance to come home. Although the entire population of Kyrgyzstan was well educated, it was the Russians and other Europeans who often held high positions,and their exit caused important shifts in the labour market. In the 1989 population census, a slight majority of the people claimed Kyrgyz ethnicity. Russians formed the second largest group, and together with other Slavic groups they formed almost a third of the population. In the 1999 census, almost two-third of the population claimed Kyrgyz ethnicity, and the Uzbeks had become the second largest group (see table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Ethnic groups in Kyrgyzstan according to the 1989 and 1999 population census.

In the Soviet Union, ethnicity (natsionalnost) was registered in individual passports. After independence, the passport entry was removed, but soon re-installed. Natsionalnost (Kyrgyz: ulut) had become an important identity marker, and both the population and administration did not want to do without it.

Outside of Kyrgyzstan, there are a number of Kyrgyz communities. In China, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and until recently Turkey, there are groups of ethnic Kyrgyz who settled there after they fled the Soviet regime, or who found themselves outside when the borders were drafted. Nomadic movement and transhumance were not taken into account when the national boundaries were determined.

Religion

After 70 years of Soviet governance, it seems odd to find religion so much alive in Kyrgyzstan. However, the Soviet Union was officially committed to freedom of religion, although it also agitated against the anti-class interests of organised religions (Stalin, 1948:77). Thus in Soviet times, the republics of Central Asia and several others were referred to as the Muslim Republics without a problem. There had been campaigns to open up people’s eyes to the backwardness of Islam and other religions. Many Muslims abandoned habits of wearing headscarves, praying and visiting mosques. But being Muslim remained a part of the identity of most Turkic people, entangled with their ethnic identity. So even today, being Kyrgyz is being a Muslim, and when one asks a Kyrgyz if he or she is Muslim, the answer will often be: ‘Of course, I am Kyrgyz!’ From that same perspective, a Kyrgyz friend sadly shook his head when we passed a group of Christian converts, saying: ‘And that is five less Kyrgyz…’ Other Turkic groups such as Uzbeks, Kazakhs and Tatars also combine ethnicity with (Sunni) Islam. There are also a number of non-Turkic Muslim groups in Kyrgyzstan, such as the Tajiks and Dungans.

A Muslim identity in Kyrgyzstan is more than just a derivative of ethnicity, however. Muslim practices, behaviour and believes also play a role. ‘Reading the Kuran’, an expression for the recital of the first sura of the K’uran, followed by personal prayers in Kyrgyz, is a recurring ritual through which Kyrgyz people experience and express their Muslim identity. In these prayers, the arbaktar (spirits) of one’s ancestors or of Kyrgyz heroes are often called upon. This, in combination with the importance placed on the divinity of nature, leads many observers to think of the Kyrgyz as ‘superficially Muslims with shamanistic beliefs’. As Bruce Privratsky points out in his study on Islam in Kazakhstan, however, ancestor spirits and the forces of nature play a significant role in many Muslim belief systems all over the world (Privratsky, 2001). Thus there is no need to deny the Kyrgyz claim that they are Muslims. The need is rather in adjusting the image of Islam.

Most of my informants stated that Uzbeks are ‘more Muslim’ than Kyrgyz, and Southern Kyrgyz are ‘more Muslim’ than Northerners. With this, they refer to the way people keep to the rules of Islam. Northern Kyrgyz often spoke of the way the Kyrgyz and Uzbeks of the South keep their women subordinate. Also the rules of not eating pork or drinking alcohol are kept more strictly in the South. However, although very few Northern Kyrgyz refrain from drinking alcohol, knowing that one is supposed to still reminds them of their Muslimness.