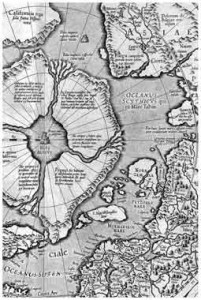

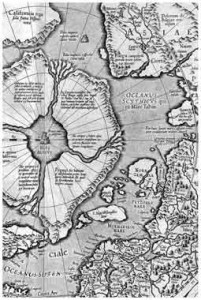

Frontispiece: Gerard Mercator’s map of the Arctic, published in his atlas of 1595. This map explains why the Dutch, discovering Spitsbergen, believed they had run into Greenland.

Being young and living idly in my native country, sometimes applying myself to the reading of histories and strange adventures, wherein I took no small delight, I found my mind so much addicted to see and travel into strange countries, thereby to seek some adventure, that in the end to satisfy myself I determined and was fully resolved for a time to leave my native country and my friends (although it grieved me). Yet the hope I had to accomplish my desire together with the resolution taken in the end overcame my affection and put me in good comfort to take the matter upon me, trusting in God that he would further my intent. Which done, being resolved, I took leave of my parents who as then dwelt at Enkhuysen, and being ready to embark myself I went to a fleet of ships that as then laid before Texel, weighing the wind to sail for Spain and Portugal. I was determined to travel to Sevilla, where as then I had two brothers that had gone there several years before; so to help myself the better and by their means to know the manner and customs of those countries and also to learn the Spanish tongue.

And the 6th of December in the year of our Lord 1576 we put out of Texel with about 80 ships and set course for Spain. 9 December we passed between Dover and Calais […]. Upon Christmas Day we entered into the river of St. Lucas de Barameda [Sanlucar de Barrameda] where I stayed two or three days and then traveled to Sevilla. On the first day of January I entered the city where I found one of my brothers. And although I had a special desire presently to travel further, yet for want of the Spanish tongue, without which one can hardly pass the country, I was constrained to stay there. In the mean time it chanced that Don Henry, the King of Portugal died, which caused great consternation and debate in Portugal for reason that the said King by his will and testament made Philip King of Spain, the son of his sister, lawful heir to the throne of Portugal. The Portuguese, always deadly enemies to the Spaniards, were wholly against it and elected to their King Don Antonio, Prior de Ocrato, brother’s son to the King that died.

The King of Spain upon receiving this news prepared himself to go into Portugal to receive the crown, sending the Duke of Alva before him to cease the strife and pacify the matter. In the end, partly by force and partly by money, he brought the country under his subjection. Thereupon many men went out of Sevilla and other places into Portugal, where they hoped to find some better means. All was quiet in Portugal and Don Antonio was driven out of the country. My brother fell sick to a disease called Tuardilha, which at that time reigned throughout the whole country of Spain, whereof many thousands died; and among the rest my brother was one [died]. Not long before the plague had been so great in Portugal that in the timespan of two years 80,000 people died in Lisboa; after which plague, the said disease ensued which wrought great destruction.

On 5 August, having some understanding in the Spanish tongue, I placed myself with a Dutch gentleman who was determined to travel into Portugal to see the country. We departed from Sevilla on 3 September and after eight days arrived at Badajos, where I found my other brother following the Court. At the same time died Anne of Austria, Queen of Spain, the King’s fourth wife; sister to Emperor Rodolphus and daughter to the Emperor Maximilian. This caused great sorrow through all Spain: her body was conveyed from Badajos to the cloister of Saint Lawrence in El Escorial, where with great solemnity it was buried. After having traveled by several towns we arrived at Lisboa on 20 September, where at the time we found the Duke of Alva being Governor for the King of Spain; the whole city making great preparation for the coronation of the King. While staying in Lisboa I fell sick through the change of air and corruption of the country. During my sickness I was seven times let blood, yet by God’s help I escaped. […] About the same time the plague, not long before newly begunne, began again to cease, for which cause the King till then had deferred his entrance into Lisboa.

On the first day of May, 1581 the King entered with great triumph and magnificence into the city of Lisboa, where above all others the Dutch had the best and greatest commendation for views, which was a bridge that stood upon the river side where the King must first pass as he went out of his galley to enter into the city, being beautified and adorned with many costly and excellent things most pleasant to behold, every street and place within the city being hanged with rich clothes of tapestry and arras. In the same year on 12 December died the Duke of Alva in Lisboa in the King’s palace. During his sickness over a period of fourteen days he received no sustenance but only women’s milk. […]

* * *

2. Van Linschoten’s Itinerario, 26. Chapter: Of The Island Of Japan

The island or the land of Japan is many islands one by the other, which are separated and divided only by certain small creeks and rivers. It is a great land, although as yet the circuit thereof is not known, because as yet it has not been explored, nor by the Portuguese sought into. It starts under 30 degrees and runs until you come to 38 degrees, lying about 80 miles east of the firm land of China.

The Portuguese travel about three hundred miles northeast from Macau. The Portuguese commonly lie in a harbor named Nagasaki, but also in others. The country is cold, proceeding of much rain, snow and ice that falls therein. It has some wheat-lands, but their common wheat is rice. In some places the land is very hilly and unfruitful. […] The country has some mines of silver. The silver is yearly brought by the Portuguese to exchange for silk and other Chinese wares that the Japanese have need of. The Japanese have among them very good craftsmen. They are sharp-witted and quickly learn anything they see. The common people of the land are much different from those of other nations, for that they have among them as great courtesy and good policy as if they had live continuously in the Court. They are very experienced in the use of their weapons as need requires, although they have little cause to use them. If anyone begins to draw his sword he is put to death. They have no prisons because he who deserves to be imprisoned is presently punished or banished from the country. When they mean to lay hold upon a man, they must do it by stealth and deceit, for otherwise he would resist and do much mischief. If it be a gentleman or man of great authority, […] he often chooses to be killed by his servants. And it is often seen that they rip their own bellies open, which is often likewise done by servants for the love of their masters. The like do young boys in presence of their parents, only for grief or some small anger. They are in all their actions very patient and humble, for that in their youth they learn to endure hunger, cold, and all manner of labor, to go bareheaded, with few clothes, as well as in winter as in summer. They account it for great beauty to have no hair, which with great care they pluck out, only to retain a pluck of hair on the crown of their heads, which they tie together.

In the land of Japan they only eat the meat of wild animals and these are hunted with great expertise. They have cattle like cows and sheep, but cannot eat those, as we refuse horse meat. They don’t take milk or milk products, like we don’t drink blood, because they say that milk although it is white, yet it is true blood. They enjoy fish, of which they have many kinds, as well as all kinds of fruit, as in China. Their houses are commonly covered with wood and straw, and built fine and workman-like, especially the rich men’s houses. […] Their manner of eating and drinking is: every man has a table alone, without table-clothes or napkins, and eateth with two pieces of wood, like the men of China. They drink wine of rice, wherewith they drink themselves drunk, and after their meat they use a certain drink, which is a pot with hot water, which they drink as hot as ever they may endure, whether it be winter or summer.

[…] The aforesaid warm water is made with the powder of a certain herb called Chaa, which is much esteemed, and is well accounted of among them. The said water is kept in a secret place and the gentlemen make it themselves, and when they entertain some friends, they give them some of that warm water to drink. The pots wherein the herb is kept, with the earthen cups they drink it in, are esteemed as much as we do of Diamonds, Rubies, and other precious stones,and they are not esteemed for their newness, but for their oldness, and for that they were made by a good workman. To know and keep such by themselves, they take great and special care. As with us the goldsmith values silver and gold: so if their pots and cups are of an old and excellent making they are worth 4 or 5 thousand ducats or more the piece. The King of Bungo did give for such a pot, having three feet, 14 thousand ducats. They do likewise esteem much of any picture or table, wherein is painted a black tree or a black bird, and when they know it is made of wood, and by an ancient master, they give whatsoever you will ask for it. […] And when we ask them, why they esteem them so much, they ask us again why we esteem so well of our precious stones and jewels, which serve to no use. […] Their religion is much like the Chinese, they have their Idols and ministers, which they call Bon, and hold them in great estimation, but since the time of the Jesuits being among them, there have been many baptized and become Christians. The number of Christians increases daily; among those are the kings of Arima, Omura, and Bungo.

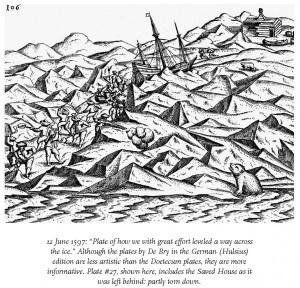

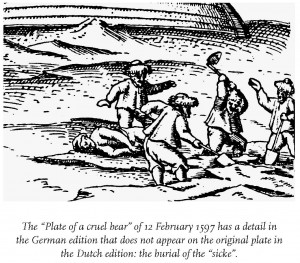

The King of Bungo is amongst the most important kings of Japan. […] They send their sons and nephews via Goa to Madrid and Rome, where they are received by the King and nobles of Spain, and the Pope,who did them great honor and bestowed many presents on them. After travelling to Florence, Venice, Ferrara, etc., they returned to Madrid with letters from Pope Sixtus, and some holy relics of the cross that Christ died on, to present to the Christian kings of Japan. In the end they arrived in India again, during my being there, which was Anno 1587, and were received with great joy. So they set sail to Japan, where again they were received with great admiration. […]

The Jesuits, then, thought it best to christen all Japanese and teach them the magnificence of the country of Europe. However, the principal reason and intent of the Jesuits was to reap great profit, and to get much praise and commendation. Most of the gifts given to them by the princes of Japan fell to their shares; they likewise obtained from the Pope and the King of Spain that no man might dwell in Japan, either Portuguese or Christian, without their license and consent, so that in all Japan there are no other orders of monks, friars, priests, but Jesuits alone. […] They have almost all of the country under their subjection; such I mean as are converted to the faith of Christ, making the Japanese believe what they wish, whereby they are honored like gods. The Japanese make such great account of them that they do almost pray to them, as if they were Saints. They had obtained so much favor of the Pope, that he granted them a bishop of their order (which is contrary to their profession), who came out of Portugal to be bishop of Japan, but died underway. […] There is not anything from which they will not suck or draw out some profit or advantage. […] It seemed in a manner that they bewitch men with their subtle practices and devices, and are so well practiced and experimented in trade of merchandise, that they surpass all worldly men. To conclude, there is not any commodity to be had or reaped throughout all India, or they have their part therein, so that the other orders and religious persons, as also the common people, do much murmur thereat, and seem to dislike of their courteous humors.

* * *

3. Gerrit De Veer’s True And Perfect Description 1598: Dedication

To the Noble, Mighty, Wise, Discreet, very Provident Lords States General of the United Provinces of the Netherlands and the Council of States, and the Provincial States of Holland, Zeeland, and West Friesland – and also the Serene Highness and lord Maurits, born Prince of Orange, Count of Nassau, Katzenelleboge, Vianden, Diets, etc., Marquis of Veere and Vlissingen etc., Lord of Saint Vith, Doesburg, the town of Grave and the Land of Cuijk etc., Stadholder and Commander-in-chief of Gelderland, Holland, Zeeland, West-Friesland, Utrecht en Overijssel etc. and Admiral at Sea; and to the Noble, Honorable, Wise, Discreet Lords the Commisioners of the Admirality in Holland, Zeeland, and West-Friesland. Gentlemen. The art of navigation exceeds in utility all other arts; during the past years this science has wonderfully improved and has brought especially our countries great prosperity, notably by skilful piloting, and experience in the measuring of latitudes and bearings of countries according to the rules of mathematical science; as a result of which we sail to all countries lying at the very end of the world and return their products. This demonstrates that the science of navigation, which has emerged from cosmography, is of greater service than any other in the world, because she does not merely offer science, but also has application in the description of bearings, courses, capes, promontories and their respective coordinates, which have not even been mentioned by Ptolemy or Strabo and remained unknown long after those two existed, but which have come to our knowledge as a result of research and development of this knowledge. Many places that were previously unknown have only been found after repeated effort, and likewise attempts by our countries investigating whether one would be able to find a passage to the Kingdoms of Cathay and China round by the North, which have been unsuccessful until now, do not remain entirely fruitless or hopeless.

To the Noble, Mighty, Wise, Discreet, very Provident Lords States General of the United Provinces of the Netherlands and the Council of States, and the Provincial States of Holland, Zeeland, and West Friesland – and also the Serene Highness and lord Maurits, born Prince of Orange, Count of Nassau, Katzenelleboge, Vianden, Diets, etc., Marquis of Veere and Vlissingen etc., Lord of Saint Vith, Doesburg, the town of Grave and the Land of Cuijk etc., Stadholder and Commander-in-chief of Gelderland, Holland, Zeeland, West-Friesland, Utrecht en Overijssel etc. and Admiral at Sea; and to the Noble, Honorable, Wise, Discreet Lords the Commisioners of the Admirality in Holland, Zeeland, and West-Friesland. Gentlemen. The art of navigation exceeds in utility all other arts; during the past years this science has wonderfully improved and has brought especially our countries great prosperity, notably by skilful piloting, and experience in the measuring of latitudes and bearings of countries according to the rules of mathematical science; as a result of which we sail to all countries lying at the very end of the world and return their products. This demonstrates that the science of navigation, which has emerged from cosmography, is of greater service than any other in the world, because she does not merely offer science, but also has application in the description of bearings, courses, capes, promontories and their respective coordinates, which have not even been mentioned by Ptolemy or Strabo and remained unknown long after those two existed, but which have come to our knowledge as a result of research and development of this knowledge. Many places that were previously unknown have only been found after repeated effort, and likewise attempts by our countries investigating whether one would be able to find a passage to the Kingdoms of Cathay and China round by the North, which have been unsuccessful until now, do not remain entirely fruitless or hopeless.

Hence I have made a short description of the aforementioned journeys (in the last two of which I was engaged) sent from our countries, along the north of Norway, Muscovia, and Tartaria to the named Kingdoms of Cathay and China, because during these voyages many noteworthy events have passed. I think that the right course may still be discovered, as the direction and position of Vaygach and Novaya Zemlya are now ascertained, as well as the eastern cape of Greenland (as we call it) at 80 degrees [Spitsbergen], in a location where it was formerly believed that there would be only water and no land, and there at 80 degrees it is less cold than at Novaya Zemlya at 76 degrees. At those 80 degrees in June early in the summer there was grass and green things growing and animals were grazing, while at 76 degrees in August, during the peak of summer, there was neither any green leaves nor grass, nor animals that feed on grass. From this it appears that not the proximity of the Pole causes the ice and cold, but the Tartarian [Kara] Sea (called the Ice Sea) and the proximity of land, where the ice floats close to. Because in the open sea between the land at 80 degrees and Novaya Zemlya, which lie 200 [German] miles [1260 km] apart ENE and WSW, there was little or no ice, but soon as we approached land, we immediately entered into cold and ice; yes because of the ice we knew we were close to land, before we could even see it.

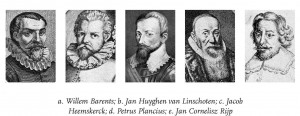

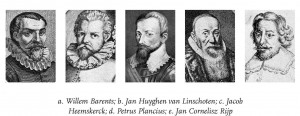

Furthermore on the east side of Novaya Zemlya, where we wintered, the ice drifted away with W and SW wind and returned with NE wind. From all this it appears that between both lands there is an open sea and that it is possible to sail much closer to the pole than has previously been assumed. And notwithstanding the ancient writers, who argue that the sea within 20 degrees of the pole is unnavigable because of the intense cold and that on account of the cold nobody can live there, we have been at 80 degrees and at 76 degrees with limited means have passed the winter. It therefore seems that between those lands one would be able to complete the voyage holding a NE course from Norway’s North Cape. This too was the opinion of Willem Barents, the famous navigator, and Jacob Heemskerck, our captain and supercargo; that they, if they would hold that course, would succeed if God granted them to. Notwithstanding that during our last journey through our manifold difficulties we were totally exhausted and often in peril of death, yet it did not break our courage and if our ship (which remained locked in the ice) had been released in time, we would once more have ventured on that same course to demonstrate that we believe that it can be done, although this last journey had been very difficult and we (speaking without vanity) have not avoided any labor, effort, or danger to come to the desired end, as the story will show; but neither time nor fate permitted it. And because the said three journeys occurred at Your Lordships’ expenses and the result that would have come out of it would have been Yours, I have taken the liberty of dedicating this narrative (which if not an eloquent, is at least a faithful one) to Your Lordships. Praying to God that he will bless Your Lordships’ wise government, in the honor of His name, and for the prosperity of these States, from Amsterdam, the last day but one of April, in the year 1598, Your noble, mighty, illustrious, E., wise, provident Lordships’ indebtedly, Gerrit de Veer

* * *

4. Gerrit De Veer’s True And Perfect Description: Introduction

It is a most certain and assured assertion, that nothing doth more benefit and further the common-wealth (specially in these countries) than the art and knowledge of navigation, in regard that such countries and nations are mighty and strong at sea, have the means and ways to draw, fetch, and bring the principal commodities and fruits of the earth […], and carry and convey to the same places such wares and merchandise whereof they have great store and abundance […]. There are continually more voyages made and strange coasts discovered; perhaps not in a first, second, or third journey but [only in full extent] by continuance of time reaped. […] As long as the results are useful, there is no more meaningful exertion than toil in the common good and benefit of all men, whatever the unskillful, disdainers, and deriders of men’s diligence may say. […] The famous navigators Columbus, Cortez, [Vasco] Nonius [de Balboa], and Magellan, (who discovered distant islands and kingdoms) […] did not leave off and give over their navigation after the first voyage […] Alexander the Great (after he had won Greece and from there Little and Great Asia) said: ‘If we had not gone forward and persisted in our intent, doing what others found impossible, we would have stayed at Sicily instead of going through all those great countries, for there is nothing that is started and completed at the same time’. To which end Cicero wisely said: ‘God has given us some and not all things so that our successors will have something to do’. Therefore, one shouldn’t stop midway whenever there’s even the remotest chance of some achievement, for the greatest and richest treasures are the hardest to find. […] Let us look to the White Sea north of Muscovy that is now so commonly sailed. Is this not the same long voyage it was before it had become completely explored? True, but finding the correct route, previously requiring reconnoitering via careful cruising, has made the difficult voyage a routine. […]

It is a most certain and assured assertion, that nothing doth more benefit and further the common-wealth (specially in these countries) than the art and knowledge of navigation, in regard that such countries and nations are mighty and strong at sea, have the means and ways to draw, fetch, and bring the principal commodities and fruits of the earth […], and carry and convey to the same places such wares and merchandise whereof they have great store and abundance […]. There are continually more voyages made and strange coasts discovered; perhaps not in a first, second, or third journey but [only in full extent] by continuance of time reaped. […] As long as the results are useful, there is no more meaningful exertion than toil in the common good and benefit of all men, whatever the unskillful, disdainers, and deriders of men’s diligence may say. […] The famous navigators Columbus, Cortez, [Vasco] Nonius [de Balboa], and Magellan, (who discovered distant islands and kingdoms) […] did not leave off and give over their navigation after the first voyage […] Alexander the Great (after he had won Greece and from there Little and Great Asia) said: ‘If we had not gone forward and persisted in our intent, doing what others found impossible, we would have stayed at Sicily instead of going through all those great countries, for there is nothing that is started and completed at the same time’. To which end Cicero wisely said: ‘God has given us some and not all things so that our successors will have something to do’. Therefore, one shouldn’t stop midway whenever there’s even the remotest chance of some achievement, for the greatest and richest treasures are the hardest to find. […] Let us look to the White Sea north of Muscovy that is now so commonly sailed. Is this not the same long voyage it was before it had become completely explored? True, but finding the correct route, previously requiring reconnoitering via careful cruising, has made the difficult voyage a routine. […]

* * *

5. Barents Reaches His Northernmost Latitude In 1594*

The 29th of July [1594] the height of the sun was taken with the cross-staff, astrolabium, and quadrant and found to be 32 degrees above the horizon. Because her declination is 19 degrees this subtracted from 32 degrees leaves 13, which subtracted from 90 gives 77 degrees. Here the nearest north point of Novaya Zemlya, called the Ice Cape, lay right east of them. There they found certain stones that glittered like gold, which for that reason they called gold-stones, and they had a faire bay with sandy ground. […] From the Ice Cape they went east a little south 6 miles to the Islands of Orange; there they tacked between the land and the ice, with fair still weather, and upon the 31 of July [1594] got to the Islands of Orange. And on one of those islands they found about 200 walruses or seahorses, lying upon the shore to bask themselves in the sunne. This seahorse is a wonderful strong monster of the sea, much bigger than an oxe, which keeps continually in the seas, having a skin like a sea-calf or seal, with very short hair. It is mouthed like a lion, and many times they lie upon the ice; they are difficult to kill unless you strike them just upon the forehead. It has four feet but no ears and commonly it has one or two young at a time. And when the fishermen chance to find them on an ice floe they cast their young into the water. The mother then takes it in her arms and so plunges up and down with it, and when she will revenge herself on one of the boats, she casts her young from her again and with all her force will attack that boat, whereby our men once were in no small danger, for that the sea horse had almost stricken her teeth into the stern of the boat with the intention to overthrow it […]. They have two teeth sticking out of their mouths, on each side one, each being about half an ell long, and these are esteemed to be as good as any ivory or elephant’s teeth, specially in Muscovia [Russia], Tartaria [Siberia], and thereabouts where they are known (Note: In 1594 one Francis Cherry imported 595 kg (1311 lb) of walrus ivory from Arctic Russia [Vaughan 1994]). Our men, supposing that they could not defend themselves being out of the water went on shore to assail some sea horses that lay basking on the beach, to get their teeth that are so rich, but they broke all their hatchets, cutlasses, and pikes in pieces and could not kill one of them, but [285] struck some of their teeth out of their mouths, which they took with them. […]

Willem Barents had begun his journey on the 5th of June 1594 and set sail out of Texel, arriving before Kildin Moscovia on the 23 of the same month, and then set course to the north side of Novaya Zemlya, wherein he continued to the 1st of August till he came to the Islands of Orange […]. Finding that he could hardly get through, to accomplish his intended voyage, his men began to become weary and refused to sail further, so they agreed to turn back and meet with the other [Zeeland and Enkhuizen] ships that had set course for Vaygach to find what discoveries had been made there.

Appendices

* De Veer copied the journal of the first expedition, in which he did not participate, probably from Barents’ log, converting ‘we’ into ‘they’ (errata on e.g. 18 and 23 July 1594). On the map the farthest point reached during this first expedition is named Cape Desire, signifying the desire to continue across the Pole, which translated into Russian has become Mys Zhelaniya.

* * *

6. Jan Huyghen Van Linschoten ’s Voyage Round By The North 1601

[Introduction] According to the writings of the Ancients, like those of Nepos, Pliny and others, there is a way round by the north to Cathay (northern China) and China. Some Indians that came from the Far East fell through a storm on the Norwegian coast. Hence it is certain that they came into the Atlantic Ocean by way of Strait Yugor. So why is it that this passage is so hard to find? […] On the 11th [September 1595] the Admiral called another meeting to consider whether we would undertake one more attempt and see whether we would be able to get through. So was decided. We set sail under a stormy wind but after three hours large ice masses obstructed our further progress and we laveered back to the Twist Cape (Cape Quarrel) and from there through open water to the Cross Cape. Here we anchored because the storm intensified. I used the opportunity the measure the tides and the direction of flow of low tide and high tide.

This strengthened my opinion that the sea east of the strait is a continuing sea. Several men went ashore and discovered a whale stripped by the Samoyedes. The cheekbones measured 16 feet. They brought five for display as oddity in our country. One may see them in the Doelen in Enkhuizen and another one in the city hall of Haarlem; I presented them to these cities for eternal memory, and love for patria.

[13 September 1595] The storm came from the SW and grew so powerful that it seemed as if heaven and earth united. We lowered all sails and dropped a second anchor. Our boats filled with water and in the midst of the tempest we feared that our lines and anchors would not hold. The skippers said that they had never experienced anything like this; however the storm passed without causing damage. Now that I have been through this it does not surprise me that there is so much driftwood high on the beaches. […] To our dismay we saw large amounts of ice floating back into the Yugor Strait. We immediately hauled the anchors and tacked about past the Cross Cape. During the night Vaygach had been covered with snow. We were much surprised to see the ice return because it had seemed as if the storms of the past few days had cleared the way for at least six days’ sailing. From this we understood that we should not hope that the situation would improve this year. Under sail we gathered on the admiral’s vessel and prepared a statement to summarize the reasons that would make us decide to return home. This statement is: ‘Today the 15th of September 1595 we met near Cross Cape on the orders of Admiral Nay and each without further dissimulation gave our opinion as to what could be done within the breadth of our instructions.

[13 September 1595] The storm came from the SW and grew so powerful that it seemed as if heaven and earth united. We lowered all sails and dropped a second anchor. Our boats filled with water and in the midst of the tempest we feared that our lines and anchors would not hold. The skippers said that they had never experienced anything like this; however the storm passed without causing damage. Now that I have been through this it does not surprise me that there is so much driftwood high on the beaches. […] To our dismay we saw large amounts of ice floating back into the Yugor Strait. We immediately hauled the anchors and tacked about past the Cross Cape. During the night Vaygach had been covered with snow. We were much surprised to see the ice return because it had seemed as if the storms of the past few days had cleared the way for at least six days’ sailing. From this we understood that we should not hope that the situation would improve this year. Under sail we gathered on the admiral’s vessel and prepared a statement to summarize the reasons that would make us decide to return home. This statement is: ‘Today the 15th of September 1595 we met near Cross Cape on the orders of Admiral Nay and each without further dissimulation gave our opinion as to what could be done within the breadth of our instructions.

After it has been concluded that we have tried our utmost to answer to our duty and responsibility we declare that God does not want to grant us success and the ice has prevented us from reaching our destination. [The continued presence of sea ice] we explain from last year’s severe winter. [De la Dale: The most severe winter in living memory [Mollema 1947]; Therefore we unanimously decided that we should use the first opportunity to sail home in order to save our ships and escape the onset of freezing and winter, protesting before God and the world that we fulfilled our duty and trusting that all the signatories would never speak differently, that we would continue to defend our point of view and that our logs should show the same. To ensure that on return there would not be any rumors started or blame spread that could damage our reputations, even though we voluntarily faced dangers for the glory of our fatherland, we agreed to sign this declaration, which has been composed by Jan Huyghen van Linschoten with Francois de la Dale’. […]

On this day we had a breeze from the NE and during the night sailed out of the strait. Snow showers and hail accompanied our departure as heralds of winter. It was so cold that our sail hardened and my breath froze into my moustache. The water however was free of ice with just the individual floe. It seems to me that this confirms the information of the Samoyeds and Russians that there is a passage between Vaygach and Novaya Zemlya, through which the ice is transported into the Kara Sea. […] Between Novaya Zemlya and Cape Tabin [Cape Chelyuskin] there must be a channel as between the heads of Dover and Calais. This stops the ice from floating east or north and it assembles into large ice fields and wind nor sea have sufficient power to break the ice, because the ice fields dampen the sea and prevent swell, which normally breaks the ice. The warmth of the sun one can easily forget because it means nothing in this region. […]

On the 24th the weather worsened beyond description. Hailstorm followed on hailstorm, the sea and the heavens became one and it was dark so we could not see a ship’s length ahead. During a short clearing we saw straight ahead snowcovered land, where we would certainly have run aground because our estimated position was 20 miles out of the coast. The maps of this region are not good […]. The next day the sky cleared; some showers remained, but the fury of the past few days had gone. We guessed that the land we had seen yesterday was Svyatoi Noss [Kola Peninsula]. We tacked about to and from the coast but did not make much progress. […]

[28 September 1595] Around this time scurvy started to spread. It began with stiffness in the limbs and waist and rotting gums, which was painful to see. The cold and nasty humidity causes all this. Also the lack of refreshing and clean clothes did much damage; it felt terrible to be helpless against these threats. […]

[8 October 1595] Weather was boisterous and dark again. During the night our yachts got separated from us and we continued with the Admiral. In the evening the sun appeared, which surprised us because we hadn’t seen her for a long time. Soon the wind increased from the north and to our joy we were able to sail west again. We thank God passed the North Cape and the northern winds did no longer hinder us; on the contrary it brought us much pleasure. […] We estimated our latitude to be 73.5 degrees. On the 9th there was such a powerful snowstorm that the entire ship was covered by it. It was so cold that we were unable to manipulate the main sail and had to beat it with sticks before we were able to set it […] Due to poor sight we also lost track of the Admiral and continued by ourselves. Overall we made good progress. […] In the rare clear nights there is much more light here than in our country, the stars almost shine as bright as the Moon. If one happens to have a clear night one may see the amazing radiation of the ‘northern light’ as seamen call this phenomenon, a play of colored rays, which emits a wonderful light that fills a man with awe. Anyone, who sails in the High North knows the ‘northern light’ and in this region it occurs frequently when the winter night draws near.

On the 12 [October 1595] we saw the sun and could finally measure an afternoon height. Our latitude appeared to be 73°20′ and we estimated to be off the coast of Tromsø. This is the same latitude as Vaygach, Kanin, or Svyatoi-Nos, but here it wasn’t as cold as it was there, even though it was later in the season. This is remarkable but one may explain it from the large amounts of sea ice near Vaygach, which probably severely cool the air. It remains an open question why in these areas, even when there is no ice, it can be so much colder than west of the North Cape. Our human intellect cannot grasp: we are too insignificant to fathom God’s wonders.

On the 12 [October 1595] we saw the sun and could finally measure an afternoon height. Our latitude appeared to be 73°20′ and we estimated to be off the coast of Tromsø. This is the same latitude as Vaygach, Kanin, or Svyatoi-Nos, but here it wasn’t as cold as it was there, even though it was later in the season. This is remarkable but one may explain it from the large amounts of sea ice near Vaygach, which probably severely cool the air. It remains an open question why in these areas, even when there is no ice, it can be so much colder than west of the North Cape. Our human intellect cannot grasp: we are too insignificant to fathom God’s wonders.

Who in ancient times would have believed that one may be able to navigate the ‘Zona frigida’ north of the Arctic circle, yes that even people are living there. Likewise people did not believe that the ‘Torrida zona’ is navigable and habitable. Here the scorching-sweltering heat, there the unbearable cold would prohibit it. And still the unthinkable has appeared to be possible, as I have found, although I must admit that the intemperate of the Cold Zone is incomparably worse than that of the tropics. It is understandable because what should one expect in October at a latitude of 74°N, when the sun has a southern declination of 7° and therefore is 81° distant. Something like that was unimaginable to the Ancients and it still makes us feel humble. […]

On the 15th we crossed the Arctic Circle and had finally escaped the intemperate zone. The wind blew from the north but it was warmer than the warmest winds around the North Cape, although our latitudes do not differ that much. The explanation I gladly leave to those who are more familiar with the sciences of physics and astronomy and heavenly effects; I leave the rest to the care of God. […] On the 18th we sighted Statland at 62°10’N, we saw a sail on the lee side and were hoping it was one of ours, but it disappeared in the coast so it was probably a Norwegian. With quick pace we sailed along the coast, which did not show any snow. This is quite a miracle because at the North Cape it snowed and hailed continuously and here it wasn’t any colder than with us in Fall. How does this agree with the hypothesis of the learned astronomers and cosmographers in our country, who, without any personal experience maintain that at 60° it is as cold as at 70°? If these gentlemen would themselves ever sail along, they would certainly learn to appreciate observation more than theoretical knowledge. […]

On the 24th [October 1595] the storm settled but a good breeze continued. The water became whitish and earthy so that we estimated to have reached the south side of the Dogger Bank, which during the night we probed at 15 fathom [~25.7 m]. The sky cleared during the evening and at night in the moonlight we sailed between the herring boats and contacted one. They informed us that Texel was to the SE, which agreed with our estimate. We passed another fisherman the next day and then a Rotterdammer coming from Norway. In the afternoon we spotted the coast of our fatherland. We got a bearing on the cathedral of Haarlem and put our location between Beverwijk and Zandvoort. About three miles off the coast we sailed north and the 26th we anchored on the roadstead of Texel. We had been out for four months and came home the majority of the men sick from scurvy and other illnesses. On our home journey we mourned two deaths: the bottler who died four days before our return and the provost who passed away in the night of our sailing inside. We could therefore bury the provost in Huisduinen a grave in the earth. We found out that there was no word on any of the other ships from our expedition and prayed to God to bring them home safely. With this the Principalest King and Lord is glorified and praised from now to eternity Amen.

Conclusion or Epilogue. The above is the account of our farings during the journey of 1595; from day to day, from hour to hour I accurately kept notes without adding or removing anything later. I hope and expect that my fellow travellers [Barents] will acknowledge the truth of what has been put down. Our principals who no doubt had been inspired by God commissioned this great endeavor without caring for costs and although God did not want us to succeed, because a lengthy winter had barely ended, I am of the opinion that we should not give up this cause and should not forget our heroic attempt. More research is needed to get insight into the possibilities. The greater the effort and objections, the more respectable the work is and the purer the ultimate triumph.

The backdrops have not been so severe that we should consider the northern seaway impossible. Seasons do differ and we experienced that. The Portuguese didn’t discover the east Indies on their first journey. Many years passed before they found the right conjunction of circumstances and before that, their efforts were in vain. […]

Should your Lords however be of the opinion that enough has been done and we should let the matter rest, then I still have the submissive request to grant me the right for publication* of my journals and drawings, in order to let truth prevail and the Prince, and you, My Lords, who took the laudable initiative for the venture, will get your well-deserved praise for your involvement. Through my work the world will know what has been done and found and all rumors and

false messages that are sold with the necessary adornments will be silenced. My journals may inspire others to continue on the road travelled, and this would be my greatest reward for all trouble and dangers. Also the Lords can be assured that I will be available when I am needed in their service.

* On 20 May 1597 Van Linschoten was awarded for 10 years the rights to publish both journals. Penalty for infringement on these rights was set at 600 Flemish pounds, a third of which was to be made out to the author, a third to the executor, and a third to the poor [translated from Mollema 1947, p. 204–213].

* * *

7. Van Linschoten ’s Round By The North 1601: The Beginning Of Whaling

[14 July 1594, between Kolguev Island and the mainland] we entertained ourselves with the whale hunt. Some of those animals came swimming onto our roadstead; we jumped into the boats and drove some in shallow water, but for lack of harpoons we could not do much more. At last we caught one, we threw a harpoon in its back which caused him to swim around fiercely, while the water colored red with its blood. The boats chased it until it was exhausted and had to give up the fight. Then the men towed it onto the shore and skinned it; the blubber was packed in barrels to make train oil. It was a young animal but already fearful to behold. The monster was 34 feet long, its tail 8 feet wide, and on both sides of the lower jaw it had 268 feathers, which are called baleens. We won 20 barrels of blubber from this animal, but the meat, guts, and skin we left as unusable waste, and also the liver which alone weighed three tons. We did not have enough barrels to store it all. As we were cutting the whale, his partner often surfaced at a stone’s throw and watched the spectacle. We could easily have caught it but let him be because we did not have enough barrels. The whales came close to shore every evening; they appear to breed here. Whale hunting would be profitable if one came here well equipped.*

Appendices

* De Moucheron was quick to speculate with this bit of information in his letter to the States of Holland and Zeeland on 6 April 1595 (Chapter 4): “A large part of the costs of a fortification [of the Yugor Strait] can be won back with the letting out of permits for whale hunting and the hunt of seal and walrus. Train oil represents a value greater than the expenses of a fort, because these animals abound in the sea”. Although whales had been known for more than twenty years for their industrial potential as a resource of train oil and baleens, Van Linschoten described the killing of the first known whale to fall victim to Europeans other than Basques [Vaughan 1994]. The whale bone found on Vaygach Island and kept in Haarlem’s City Hall (11 September 1595) suggests that this whale was a bowhead (Balaena mysticetus), the only large whale species endemic to the Arctic, today almost extinct.

* * *

8. De Veer: Encounter With The ‘Samoyeds’

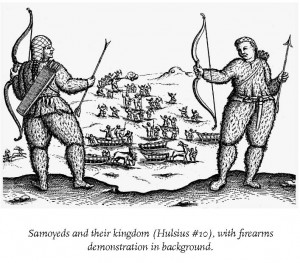

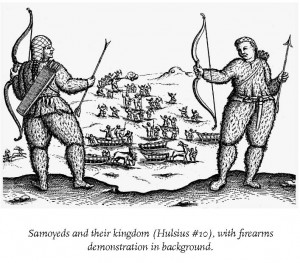

Their apparition is like we used to paint wild men; but they are not wild, because they are of reasonable judgement. They dress in deer skins from head to feet, unless it be the chief among them, which, man or woman, are dressed like the others, as said, except for their heads, which they cover with a colored cloth lined with fur. The others wear caps of deerskin, with the rough side out, which close around their heads. They have long hair, which they braid with a long tail on their backs. They are (most of them) short and of low stature, with broad flat faces, small eyes, short legs, their knees standing outward, and they are very quick […] Their sledges stood always ready with one or two deer, which run so swiftly with one or two men in them that our horses would not be able to follow them. One of our men shot a musket towards the sea, wherewith they were in such great fear that they ran and leapt like mad men; yet at last they calmed down when they perceived that it was not maliciously done to hurt them. We told them by our interpreter, that we used our pieces instead of bows, whereat they wondered, because of the great blow and noise that it gave. To show them what we could do with [our muskets], one of our men took a flat stone about half and a handful broad, and set it upon a hill a good way off from him. They perceived that we meant [to demonstrate] somewhat thereby, and fifty or sixty of them gathered around us, yet somewhat far off. He with the musket shot it and when the bullet smashed the stone in pieces they wondered even more than before. After that we parted, with great friendship on both sides; and when we were in our boat, we all put off our hats and bowed our heads unto them, sounding our trumpet. They in their manner saluted us and then went back to their sledges [31 August 1595].

Their apparition is like we used to paint wild men; but they are not wild, because they are of reasonable judgement. They dress in deer skins from head to feet, unless it be the chief among them, which, man or woman, are dressed like the others, as said, except for their heads, which they cover with a colored cloth lined with fur. The others wear caps of deerskin, with the rough side out, which close around their heads. They have long hair, which they braid with a long tail on their backs. They are (most of them) short and of low stature, with broad flat faces, small eyes, short legs, their knees standing outward, and they are very quick […] Their sledges stood always ready with one or two deer, which run so swiftly with one or two men in them that our horses would not be able to follow them. One of our men shot a musket towards the sea, wherewith they were in such great fear that they ran and leapt like mad men; yet at last they calmed down when they perceived that it was not maliciously done to hurt them. We told them by our interpreter, that we used our pieces instead of bows, whereat they wondered, because of the great blow and noise that it gave. To show them what we could do with [our muskets], one of our men took a flat stone about half and a handful broad, and set it upon a hill a good way off from him. They perceived that we meant [to demonstrate] somewhat thereby, and fifty or sixty of them gathered around us, yet somewhat far off. He with the musket shot it and when the bullet smashed the stone in pieces they wondered even more than before. After that we parted, with great friendship on both sides; and when we were in our boat, we all put off our hats and bowed our heads unto them, sounding our trumpet. They in their manner saluted us and then went back to their sledges [31 August 1595].

* * *

9. Through The Arctic Night And Observation Of The ‘Novaya Zemlya Effect’

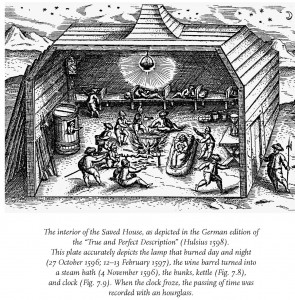

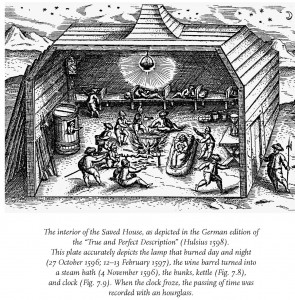

15 December [1596] it was bright weather. That day we caught two foxes and saw the moon rise ESE, when it was 26 days old, in the sign of Scorpio. [On 16 December] we had no more wood in the house and had to go out to get more, which we had to dig out of the snow. […] This we did taking turns, two and two together, wherein we were forced to use great speed, for we could not long endure without the house, because of the inexpressible, intolerable cold, even though we wore the fox skins on our heads and double apparel on our backs. […] On 18 December we went out to the ship to see how it was and hoping to catch a fox. Below decks we found none but in the hold when we had stricken fire to inspect the water level we discovered a fox, which we caught and brought to the house to eat, and found that in eighteen days the water had risen about a finger and the barrels with drinking water we brought from Holland were frozen solidly.

19 December it was fair weather with a wind from the south. Then we comforted each other that the sun was on the other side of the globe and ready to come to us again. We sorely longed for it; […] the greatest comfort that God sent onto man here upon the earth and that in which every living thing rejoices.

[…] The 22nd of December it was foul weather with lots of snow and wind from the southwest, blocking our door again, so we had to dig ourselves out, which we now did almost every day. 23 December, foul weather, wind southwest with lots of snow, but we were comfortable knowing that the sun was on its way to us again, for (we calculated) that day it had reached the Tropic of Capricorn, which is the utmost limit it reaches before returning north. This Tropicus Capricorni lies south of the equinoctial line at 23 degrees and 18 minutes.

24 December, Christmas eve, it was fair weather. Then we opened our door again and though there was no daylight we could see much open water in the sea, as we had heard the ice crack and drive. […] On Christmas day it was foul weather with northwest wind and despite the weather we heard foxes running over our house, wherewith some of the men said it was a bad sign. We disputed why this would be a bad sign and some of our men answered it would be better if we could catch some and put them in the pot or on the spit, then it would have been a very good sign. On the 26 with foul weather it was so extraordinarily cold that we were unable to keep ourselves warm, by all means: with a large fire, extra clothes, and heated stones and cannon balls around our feet and body as we lay in our bunks. In the morning the bunks were frosted white which made us behold one the other with sad countenance. But we comforted ourselves again as well as we could that the sun was on its way back to us and as the proverb goes ‘days that lengthen are days that strengthen’; hope put us in good comfort and eased our pain. […]

24 December, Christmas eve, it was fair weather. Then we opened our door again and though there was no daylight we could see much open water in the sea, as we had heard the ice crack and drive. […] On Christmas day it was foul weather with northwest wind and despite the weather we heard foxes running over our house, wherewith some of the men said it was a bad sign. We disputed why this would be a bad sign and some of our men answered it would be better if we could catch some and put them in the pot or on the spit, then it would have been a very good sign. On the 26 with foul weather it was so extraordinarily cold that we were unable to keep ourselves warm, by all means: with a large fire, extra clothes, and heated stones and cannon balls around our feet and body as we lay in our bunks. In the morning the bunks were frosted white which made us behold one the other with sad countenance. But we comforted ourselves again as well as we could that the sun was on its way back to us and as the proverb goes ‘days that lengthen are days that strengthen’; hope put us in good comfort and eased our pain. […]

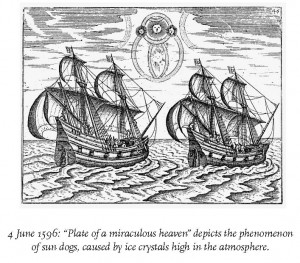

The 24th of January [1597] it was fair calm weather, with a southwest wind. The four of us went to the ship and comforted each other, thanking God that the most difficult part of winter had passed, in good hope that we would live to talk of those things back home in our own country. While we were in the ship we found that the water in it had risen higher. We all took a biscuit or two and went back. On the 24th it was fair, clear weather again, still with a west wind. I went with Jacob Heemskerck and another one to the end of the cape where, totally unexpected, we saw the top edge of the sun, I first, and we hurried home to tell Willem Barents and the others the joyful news. [The sun had not been seen since 4 November]. However, Willem Barents being a wise and experienced pilot did not believe it, estimating that it was fourteen days too soon for the sun to shine in this part of the world. We earnestly affirmed that we had seen the sun and bets were laid. The next days it was misty and overcast and we couldn’t see anything. Those who betted against us thought they had won, but the 27th it was clear and bright weather and we all saw the sun in its full roundness above the horizon. [This observation] was clean contrary to the opinions of all old and new writers, yes, contrary to the nature and roundness both of heaven and earth. Some of us said that because we had lived in the night for such a long time we might have overslept ourselves, with respect to which we well know the contrary. Considering this spectacle in itself God is wonderful in all his works, we refer for that to his almighty powers, and leave it to others to dispute. But for that no man shall think that we doubt [the accuracy of our measurements] we present some declaration thereof […]. Otherwise I leave the discussion to those who make their profession of it; suffice to say that we were not mistaken with respect to the time.

* * *

10. Escape From Novaya Zemlya And Barents’ Dying

The 13 June [1597] it was fair weather. The master and the carpenters went to the ship and prepared the boat and the sloop. The master and those that were with him, seeing that there was open water and a good west wind, came back to the house and he said to Willem Barents (who had long been sick) that it was a good time to leave. They resolved jointly with the ship’s company to take the boat and the sloop to the waterside and in the name of God begin our voyage to sail away from Novaya Zemlya. Willem Barents had previously written a small scroll, which he then placed inside a bandoleer and hung in the chimney. […] The master also wrote two letters, […] one for each of our sloops in case we would lose each other by storms or other misadventure […]. And so, having finished all things as we determined, we drew the boat to the waterside and left a man in it, and went back to fetch the sloop, and after that eleven sledges with goods, such as victuals and some wine that yet remained, and the merchants goods of which we took every care to preserve as much as possible, viz. 6 packs with the finest woolen cloth, a chest with linen, two packets of velvet, two small chests with money, two trunks with men’s clothes such as shirts and other things, 13 barrels of bread, a barrel with cheese, a fletch of bacon, two runlets of oil, 6 small runlets of wine, two runlets of vinegar, packs and cloths belonging to the sailors. Piled altogether one would not believe that it would fit in the boats. Which being all put away, we went to the house and first drew Willem Barents on a sledge to the waterside, and then fetched Claes Andriesz; both of them had long been ill. So we got into the boats, equally dividing ourselves between them, and with a patient in each. The master asked that the boats were aligned together so that we could sign our names under both letters. After that we committed ourselves to the will and mercy of God; with a WNW wind and open water, we set sail and put to the sea.

The 13 June [1597] it was fair weather. The master and the carpenters went to the ship and prepared the boat and the sloop. The master and those that were with him, seeing that there was open water and a good west wind, came back to the house and he said to Willem Barents (who had long been sick) that it was a good time to leave. They resolved jointly with the ship’s company to take the boat and the sloop to the waterside and in the name of God begin our voyage to sail away from Novaya Zemlya. Willem Barents had previously written a small scroll, which he then placed inside a bandoleer and hung in the chimney. […] The master also wrote two letters, […] one for each of our sloops in case we would lose each other by storms or other misadventure […]. And so, having finished all things as we determined, we drew the boat to the waterside and left a man in it, and went back to fetch the sloop, and after that eleven sledges with goods, such as victuals and some wine that yet remained, and the merchants goods of which we took every care to preserve as much as possible, viz. 6 packs with the finest woolen cloth, a chest with linen, two packets of velvet, two small chests with money, two trunks with men’s clothes such as shirts and other things, 13 barrels of bread, a barrel with cheese, a fletch of bacon, two runlets of oil, 6 small runlets of wine, two runlets of vinegar, packs and cloths belonging to the sailors. Piled altogether one would not believe that it would fit in the boats. Which being all put away, we went to the house and first drew Willem Barents on a sledge to the waterside, and then fetched Claes Andriesz; both of them had long been ill. So we got into the boats, equally dividing ourselves between them, and with a patient in each. The master asked that the boats were aligned together so that we could sign our names under both letters. After that we committed ourselves to the will and mercy of God; with a WNW wind and open water, we set sail and put to the sea.

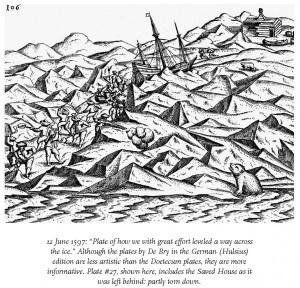

The 14th of June in the morning with the sun in the east [ca. 4 a.m.] we put off from the land of Nova Zembla and the fast ice thereunto adjoining, with our boat and sloop, and sailed ENE all day to Eylandt’s Hoek, which is five miles [1 German mile = 6.3 km: Verhoeff 1983]. We didn’t start off very well because we came between ice floes which were lying together hard and fast and it put us in no small fear and trouble. Four of us went ashore to explore the situation. In the cliffs we caught four birds, which we killed with stones. The 15th of June the ice drifted away and we went under sail again with a south wind, passing by Hooft Hoek en Vlissinger Hooft, stretching northeast to the Cabo van Begeerte (Cape Desire, Mys Zhelaniya): 13 [German] miles. There we lay until 16 June. [16 June 1597] We got to the Orange Islands with a south wind, which is 8 [German] miles from Cape Desire; there we went ashore with two small barrels and a kettle, to melt snow and put the water in the barrels, and also to search for birds and eggs for our ill, and being there we made fire with the driftwood that we found there, but we found no birds. Three of our men went over the ice to the other island and caught three birds. As they came back, our master (one of the three) fell through the ice, and feared for his life because there was a strong current, but by God’s help he came out and came to us to dry himself by the fire that we had made. […] We filled our two runlets with water that held about eight gallons a piece; which done we put to sea again with a southeast wind and nasty drizzly weather, whereby we became all damp and wet, for we had no shelter in our open boats. We sailed west to the Ice Cape and when we arrived there, we put our boats hard by each other and the master called to Willem Barents how he was doing and Willem Barents answered: ‘Well mate, thank God, I hope to walk before we get to Waardhuus’. Then he spoke to me and said: ‘Gerrit, if we come about the Ice Cape you should lift me up again, I must see that cape once more’. We had sailed from the Orange Islands to Ice Cape about 5 [German] miles and the wind went round to the west, so we attached our boats to the ice floes and there ate somewhat; but the weather became fouler and fouler and the ice enclosed us and forced us to stay there. […]

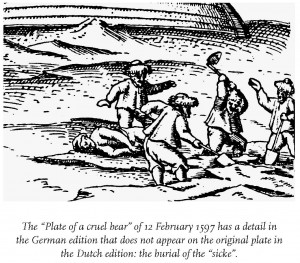

[17 June 1597] We drove away so forcefully with the ice and were pressed sorely between the ice floes that we thought verily that the boats would burst into a hundred pieces, which made us look pitifully at each other because good counsel was dear. Every instant we saw death before our eyes. At last someone suggested we should take a rope onto the fast ice, so that we may draw the sloop out of the icedrift. […] This was a good advice but no man dared to follow through for fear of drowning. In that perplexity and with little choice (it is easy to risk a drowned calf) I being the lightest of our company took it on me to carry the rope onto the fast ice, crawling from one floe to the other. With God’s help I reached the fast ice and tied the rope to a tall hill. […] As we all had gotten there in all haste we took the ill out of the boats and laid them on the ice, with clothes underneath them, and threw all our goods onto the fast ice, whereby for that moment we had escaped danger and been delivered from the jaws of death. […]

The 20 of June it was indifferent weather, the wind west, and when the sun was southeast [~7 a.m.], Claes Andriesz began to be extremely sick, whereby we perceived that he would not live long. The boatsman came into our scute and told us in what case he was and that he could not long continue alive; whereupon Willem Barents spoke: ‘I guess with me too it will not last long’. Yet we did not judge Willem Barents to be so sick, because we sat talking one with the other and spoke of many things, and Willem Barents studied the map that I had made during our voyage (and we had some discussion about it). Then he put away the map and said ‘Gerrit, can you give me something to drink’, and he had no sooner drunk or he was taken with so sudden a qualm, that he turned his eyes in his head and presently died. We had no time to call the master out of the other boat to talk to him; he died before Claes Andriesz, who died shortly after him. The death of Willem Barents put us in no small discomfort as being the chief guide and only pilot on whom we reposed ourselves. But before God we are helpless and had to submit ourselves.

The 21 of June the ice began to drive away again and God made us some opening with a SSW wind and when the sun was about NW [midnight] the wind began to blow SE with a good gale and we began to make preparations to go from thence. The next morning there blew a good gale out of the southeast and the sea was reasonably open. We drew our boats over the ice to get to it, which was a great pain and labor to us, because we first needed to go over a piece of ice [snow?] of 50 paces long and then put the boats into the water, and then again pull them onto the ice and pull them at least a 100 paces, before we would come to a place where we could get out. […]

* * *

11. Return Of The Netherlanders To The North Russian Coast In 1597

Note Table Two

* With Jan Cornelisz Rijp, the winterers returned to Maassluis (west of Rotterdam) on 29 October 1597. In two days they travelled via Delft, The Hague, and Haarlem to Amsterdam. When they arrived in Amsterdam, around noon on 1 November, the news of their return spread through the city. While reporting in at the office of the ship’s owner, Pieter Hasselaer, they were called to join a reception at the Prinsenhof and greet the burgomaster and company and the Lord Chancellor of Denmark, ambassador of the Danish King. The Prinsenhof on the Oudezijdsvoorburgwal (No. 195–199) was originally a nunnery, but after the Reformation it became a lodging for ‘princes’ and, from 1597, also the meeting place of the Amsterdam Admiralty Board. Today it is still a hotel, down the canal from Plancius’ parish and opposite the Oude Kerk, where Van Heemskerck lies buried. The reception of the winterers in the Prinsenhof, fox fur hats and all, was depicted in an engraving in Pontanus’ Rerum et Urbis Amstelodamensium Historia (1614).

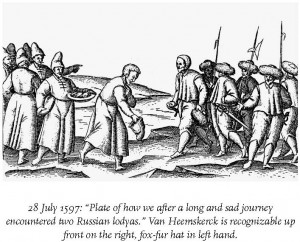

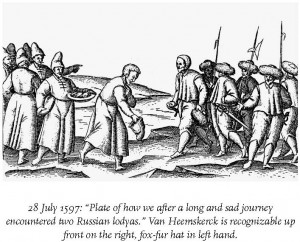

(28 July 1597] We sailed 6 miles [40 km] southeast of St. Laurens Bay or Schans Cape [southern Novaya Zemlya], when we saw two Russian lodyas, which comforted us, although we were careful for reason of their numbers, because we counted at least thirty men, and knew not what sort of persons they were; savages or other un-Dutch. With much effort we got to shore and when they saw us, they left their work and came towards us […]. Some of them knew us, because they visited our ship the year before when we past through Vaygach […]. They asked us for our ‘korabl’, meaning our ship, and we gestured as well as we could that we had lost our ship in the ice; wherewith they said: ‘korabl propal’, which we understood to be: ‘Have you lost your ship?’ and we answered: ‘Korabl propal’ […]. They expressed their grief for our loss […], and gestured that they had drunk wine in our ship [two years ago], and asked us what drink we had now. One of our men went back to the scute and drew some water, and let them taste it, but they shook their heads and said ‘No dobre’, not good […]. It had been thirteen months since we departed from Jan Cornelisz [at Bear Island] and we had not seen any man, only monsters and ravenous wild bears, so that we were in great comfort to see that we had lived so long to come in the company of man again.

[…]

[20 August 1597] Then we went on land [on the western shore of the White Sea] into the houses that stood upon the shore, where they showed us great friendship. They led us into their rooms and bade us to sit down and cooked us a dish of fish, and made us right welcome. […] They lived very poorly and ordinarily eat nothing but fish. During the evening, when we prepared ourselves to go back to the sloop, they prayed the master and me to stay with them in their houses, which the master thanked them for, and he went back to the boat, but I stayed the night. Beside those thirteen Russians, there were two Laplanders and three women with a child, which lived very poorly of the remains given to them by the Russians; a piece of discarded fish or some fish heads. We found it quite disturbing to see that their poverty was so great that those leftovers were gratefully accepted.

[20 August 1597] Then we went on land [on the western shore of the White Sea] into the houses that stood upon the shore, where they showed us great friendship. They led us into their rooms and bade us to sit down and cooked us a dish of fish, and made us right welcome. […] They lived very poorly and ordinarily eat nothing but fish. During the evening, when we prepared ourselves to go back to the sloop, they prayed the master and me to stay with them in their houses, which the master thanked them for, and he went back to the boat, but I stayed the night. Beside those thirteen Russians, there were two Laplanders and three women with a child, which lived very poorly of the remains given to them by the Russians; a piece of discarded fish or some fish heads. We found it quite disturbing to see that their poverty was so great that those leftovers were gratefully accepted.

[29 August 1597] [After four days], the Laplander returned [ from Kola], without our man, and this troubled us; but he brought us a letter that was written unto our master, which he opened before us. The writer wondered much about our arrival in that place, and that he verily thought that we had lost our lives, but that he was exceedingly glad of our arrival. […] We wondered quite a bit who it could be that showed us such great favor and friendship, and according to the letter knew us well. Although the letter was signed ‘by me Jan Cornelisz. Rijp’, we could not perceive that it was the same Jan Cornelisz who the year before had set out with us in the other ship, and left us at Bear Island.

The 2 of September in the morning we rowed up the river and as we passed along we saw trees on the sides, which comforted us and it made us glad to enter a new world, because all the time we were out we had not seen any trees. […]

With the northwest sun [in the evening] we got to Jan Cornelisz’ ship, into which we clambered and had some drinks. There we began to make merry with the seamen and were happy to see each other again. We rowed on and later that night arrived at Kola [Murmansk] where some of us went on land, and some stayed in the boats to look after our goods. To those we sent milk and other things to comfort and refresh them; and we were all exceedingly glad that God of his mercy had delivered us out of so many dangers and troubles.

[11 September 1597] By leave and consent of the boyard, governor to the King of Muscovia, we brought our scute and boat into the merchants’ place and left them there as a monument to our long, distant, and never before sailed voyage, made in those open boats along almost 400 German miles [2520 km] of coastline to the town of Kola, whereat the inhabitants thereof could not sufficiently wonder.

—————–

These fragments are from ‘The True and Perfect description ‘ were taken from William Philip’s 1609 translation, reproduced in Beke (1853 and 1876, available as facsimile edition reprinted by Elibron, n.d.), and compared with a translation of de Veer’s original text into modern Dutch by Arjaan van Nimwegen (1978, Spectrum). De Veer’s dedication, not included in the 1609 text, has been translated from Van Nimwegen’s text. Texts from the ‘Itinerario’ were adapted from the edition of John Wolfe, London 1598, facsimile edition reprinted by Johnson (Norwood, New Jersey: 1974). Texts from Van Linschoten’s ‘Voyage round by the North’ were translated from Mollema (1947) and cross-checked with the original text reproduced in L’Honoré-Naber (1914).

JaapJan Zeeberg – Into the Ice Sea – Barents’ wintering on Novaya Zemlya: A Renaissance voyage of discovery

Rozenberg Publishers, Amsterdam, 2005. ISBN 978 90 5170 926 1

Regelmatig zijn binnen en buiten de juridische discipline pleidooien gehouden om in de rechtenstudie meer plaats in te ruimen voor vakgebieden zoals de sociologie, de psychologie en de economie. Een breder opgeleid jurist zou beter bij de huidige complexe samenleving passen. Meer aandacht voor deze niet-juridische vakgebieden gaat echter ten koste van specifiek juridische vakken. Aldus komt de rechtenfaculteit voor het dilemma te staan:

Regelmatig zijn binnen en buiten de juridische discipline pleidooien gehouden om in de rechtenstudie meer plaats in te ruimen voor vakgebieden zoals de sociologie, de psychologie en de economie. Een breder opgeleid jurist zou beter bij de huidige complexe samenleving passen. Meer aandacht voor deze niet-juridische vakgebieden gaat echter ten koste van specifiek juridische vakken. Aldus komt de rechtenfaculteit voor het dilemma te staan: