Die ersten amtlichen Bevölkerungsvorausberechnungen in den 1920er Jahren.

Problemstellung

Nach dem Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs rückten die demografischen Veränderungen in den Kriegs- und Nachkriegsjahren in das Zentrum der öffentlichen Debatten. Gegenstand statistischer Analysen bildeten die Geburtenausfälle in den Jahren 1914 bis 1919, die Übersterblichkeit der männlichen Bevölkerung und die Entstehung des Frauenüberschusses, die den Altersaufbau der Reichsbevölkerung nach dem Weltkrieg prägten. Hinzu kamen die Bevölkerungsverluste, die aus der territorialen Neugliederung des Deutschen Reichs in Folge der Umsetzung des Friedensvertrages von Versailles entstanden.1 Das Statistische Reichsamt stellte sich zur Aufgabe, die Verwerfungen in der Alters- und Geschlechtsstruktur als auch die bereits vor dem Weltkrieg eintretenden Veränderungen im Geburtenverhalten zu untersuchen und deren langfristige Auswirkungen auf die Bevölkerungsdynamik zu berechnen. Binnen vier Jahren erstellte das Statistische Reichsamt zwei demografische Vorausberechnungen über die künftige Bevölkerungsentwicklung und -struktur für das Territorium des Deutschen Reiches nach 19192 (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 316, 1926 und Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 401, II, 1930). Die Grundlage für diese ersten zwei amtlichen Vorausberechnungen boten die Ergebnisse der Volkszählungen der Jahre 1910, 1919 und 1925.

Es wurden weitere statistische Erhebungen und Ergebnisse zur natürlichen Bevölkerungsbewegung im Deutschen Reichsterritorium nach dem Erstem Weltkrieg hinzugenommen (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 276, 1922; Statistik des Deutschen Reiches, 316, 1926; Statistik des Deutschen Reiches, Sonderhefte zu Wirtschaft + Statistik, 5, 1929, Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 360, 1930, Statistik des Deutschen Reiches, 401, I +II, 1930).

In der ersten 1926 erschienenen Vorausberechnung wurde die Entwicklung der Bevölkerungsdynamik und -struktur für einen Zeitraum von 50 Jahren (1925 bis 1975) und in der zweiten, 1930 erschienen, für einen Zeitraum von 75 Jahren (1930 bis 2000) und darüber hinaus erstellt.3 Nahe zeitgleich hier zu erarbeitete der Bevölkerungsstatistiker Friedrich Burgdörfer (1890-1967) eine weitere demografische Vorausberechnung.4

In diesem Beitrag werden folgende Inhalte diskutiert:

1 Die wesentlichen Veränderungen im Altersaufbau der Bevölkerung des Deutschen Reichs in Folge des Ersten Weltkrieges.

2 Die erste amtliche Vorausberechnung und die Berechnungsmodelle zur Beschreibung der strukturbedingten ehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsentwicklung und deren Auswirkungen auf den Bevölkerungsbestand und seine Struktur.

3 Die zweite amtliche Vorausberechnung und die Berechnungsmodelle zur Beschreibung des individuellen Fruchtbarkeitsverhaltens und dessen Auswirkungen auf wellenartige Geburtenausfälle.

4 Das Berechnungsmodell einer Bevölkerung mit einer stabilen Altersstruktur nach Alfred J. Lotka.

5 Bevölkerungspolitische Implikationen der amtlichen Vorausberechnungenein kurzer Exkurs

Die unmittelbaren Auswirkungen des Ersten Weltkrieges auf Bestand und Struktur der Bevölkerung

Die stetige Zunahme des Bevölkerungsbestandes kennzeichnete die demografische Entwicklung im Deutschen Reich für den Zeitraum von 1871 bis 1914. Mit dem Ersten Weltkrieg wurde diese gleichmässige Bevölkerungsentwicklung erstmals unterbrochen. Bis 1914 war nach Angaben der amtlichen Statistik die Einwohnerzahl des Deutschen Reichs auf 67,8 Millionen angewachsen. Bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkrieges registrierte die amtliche Statistik eine Abnahme der Gesamtbevölkerung von mehr als 5,9 Millionen Menschen. Hieran schloss sich in den Nachkriegsjahren eine leichte Zunahme der Gesamtbevölkerung im Verlauf der 1920er Jahre an.

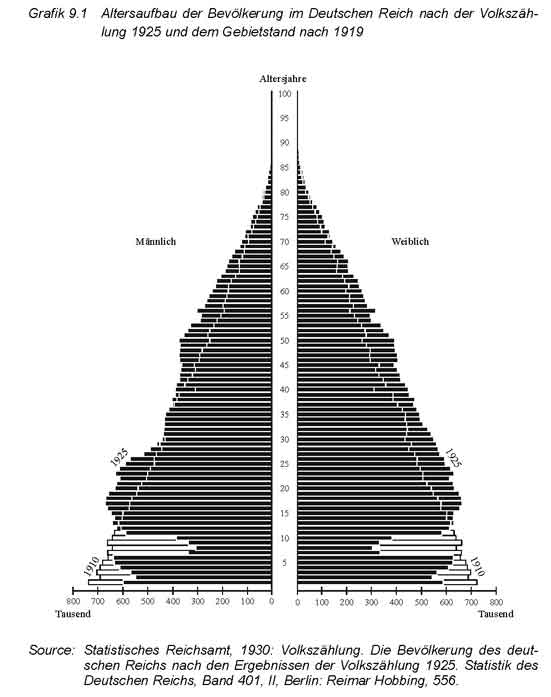

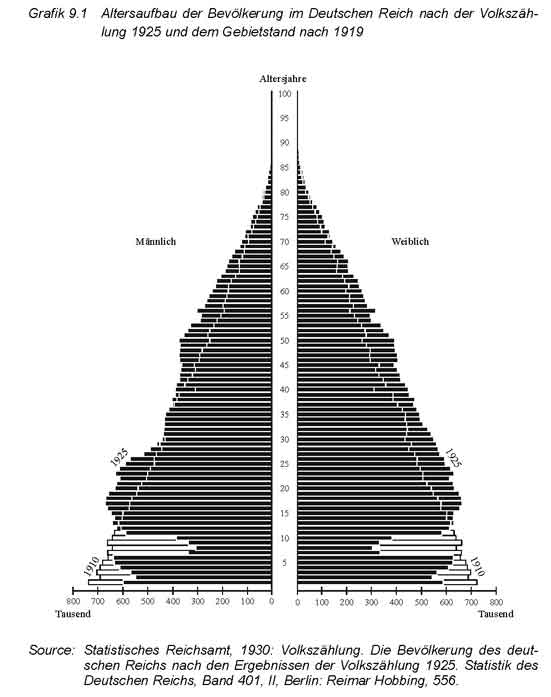

Die Auswirkungen des Ersten Weltkrieges zeigen sich bei der Gegenüberstellung des Altersaufbaus der Bevölkerung für die Jahre 1910 und 1925. Der Altersaufbau von 1925 (siehe Grafik 9.1) zeigt deutliche Veränderungen gegenüber 1910. Die amtliche Statistik beschreibt die sich wandelnde Altersund Geschlechtsstruktur mit den Worten: “Mehr Erwachsene, aber weniger Kinder.” (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 401, II, 1930, 556).

In konkreten Zahlen ausgedrückt ist 1925 im Vergleich zu 1910 der Anteil der unter 15jährigen um 17,9% zurück gegangen und der 15 bis unter 65jährigen um 20,9% sowie der über 65jährigen um 25,6% angestiegen.

Diese Verschiebungen in der Altersstruktur gegenüber von 1910 sind durch mehrere parallel verlaufende Prozesse in den Kriegsjahren verursacht worden. Die wichtigsten Komponenten sind die Geburtenausfälle und der Rückgang der Fruchtbarkeit in den Jahren 1914-1919. Sie führten zu starken Störungen in der zahlenmässigen Besetzung der unteren Altersgruppen. Der Geburtenausfall zwischen 1914-1919 wurde mit einem Geburtendefizit von ca. 3,3 Millionen beziffert. Auch in den ersten Nachkriegsjahren wurden deutlich weniger Kinder geboren als vor 1914. In Folge dieser Entwicklung nahm der Anteil der Kinder unter 15 Jahren an der Gesamtbevölkerung von Jahr zu Jahr ständig ab. 1912 betrug der Anteil der unter 15jährigen an der Gesamtbevölkerung noch 33,9% und sank durch die Fortsetzung des Geburtenrückgangs in den Nachkriegsjahren bis 1925 auf 25,8% ab (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, 558) (siehe Grafik 9.2). Zum anderem führte der Krieg zu Veränderungen der Sterblichkeitsverhältnisse, von denen insbesondere die über 20jährige männliche Bevölkerung betroffen war.5

Der in den Kriegsjahren registrierte schnelle Sterblichkeitsanstieg in den Altersgruppen der 20 bis unter 35jährigen Männer leitete grundlegende Veränderungen in dem Geschlechtsverhältnis der Deutschen Bevölkerung ein. Das proportionale Verhältnis zwischen der weiblichen und männlichen Bevölkerung in den Altersgruppen der 20 bis unter 35jährigen wurde empfindlich gestört (siehe Grafik 9.3). In diesen Altersgruppen entstand ein deutlicher Frauenüberschuss, den es bei den demografischen Vorausberechnungen zu berücksichtigen galt. Das betraf insbesondere die Berechnungen zur künftigen Geburten-, Fruchtbarkeits- und Eheschliessungsentwicklung.

Die Statistiker registrierten in ihren Erhebungen starke Veränderungen in der Entwicklung der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit in den Kriegsjahren. Um die Jahrhundertwende betrug die eheliche Fruchtbarkeitsziffer im Durchschnitt des Deutschen Reichs noch 279,7‰ und sank bis 1910/11 auf 224,5‰ ab. Zwischen 1913 und 1917 fiel die eheliche Fruchtbarkeitsziffer um nahezu die Hälfte ab und stieg geringfügig in den ersten Nachkriegsjahren. Allerdings hielt dieser Anstieg nur bis 1924/26 an. Die allgemeine Fruchtbarkeitsziffer stieg auf 143,5‰ an, doch erreichte sie damit keineswegs das Niveau der Vorkriegsjahre (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1929: Beiträge, 14f.). Neben dem Rückgang der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit wurde die Bevölkerungsdynamik und -struktur vor allem durch die veränderte Sterblichkeit beeinflusst. Besonders deutlich stieg die Sterblichkeit zu Beginn und zum Ende des Krieges und führte für die Kriegsjahre zu einem Sterbefallüberschuss.

Der entstandene Frauenüberschuss wirkte sich auf den Bestand der heiratsfähigen Frauen aus. Er zeigte sich besonders markant in den Altersgruppen der 25 bis unter 32jährigen Frauen, so dass ein nicht unbeträchtlicher Teil dieser Frauen ledig blieben und damit meist nicht an der Bildung von Familien beteiligt waren.6

Des weiteren stieg das durchschnittliche Erstheiratsalters an. 1913 betrug das durchschnittliche Erstheiratsalter für die männliche Bevölkerung ca. 27,5 Jahre, es stieg bis 1919 auf 29,0 Jahre an. Für die weibliche Bevölkerung erhöhte sich das durchschnittliche Erstheiratsalter im gleichen Zeitraum von 24,7 auf 26,0 Jahre (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1922, Bewegung, XIX.). Insgesamt wurde geschätzt, dass in den Kriegsjahren ca. 870.000 Eheschliessungen ausgefallen waren.

Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg setzte sich der Geburten- und eheliche Fruchtbarkeitsrückgang weiter fort. Dieser gab den Anlass, sich mit den Auswirkungen der gegenwärtigen Geburten- und Fruchtbarkeitsverhältnisse auf die langfristige Gestaltung des Altersaufbaus und der Bevölkerungsdynamik zu beschäftigen.

Die erste amtliche Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung von 1926

Die durchgeführten Berechnungen und Analysen sind auf die Untersuchung der natürlichen Zuwachsraten gerichtet. Gewählt wird ein makroanalytischer Ansatz, in dem die Geburten und die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit in Abhängigkeit der Verschiebungen in der Altersstruktur ermittelt werden. Im vorliegenden Berechnungsmodell wird die Frage gestellt, wie sich der Geburtenüberschuss im Berechnungszeitraum bis 1975, bedingt durch Verschiebungen in der Altersstruktur, ändern wird. Für die Vorausberechnung wird die Komponentenmethode in Anwendung gebracht.7

Für die erste demografische Vorausberechnung wurden Annahmen für die künftige Entwicklung der Sterblichkeit und der räumlichen Mobilität formuliert.

Für die Entwicklung der Sterblichkeit im Berechnungszeitraum 1925 bis 1975 wurde die altersspezifische Sterblichkeit der Jahre 1921 bis 1923 zugrunde gelegt und angenommen, dass sie sich im Berechnungszeitraum nicht verändern werde. Angenommen wurde des weiteren eine geschlossene Bevölkerung. Als ausschlaggebender Einflussfaktor für die künftige Bevölkerungsentwicklung wird die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit in Betracht genommen.8 Für die Vorausberechnungen der Geburten- und ehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsentwicklung wurden Änderungsfaktoren für die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit und für die Eheschliessungen ermittelt.9 Ausgehend von der durchschnittlichen ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit der Jahre 1924/1925 wurden Mittelwerte der altersspezifischen Fruchtbarkeit für die jeweiligen gebärfähigen fünfjährigen Altersgruppen berechnet. Damit sollte das Mass der Beteiligung der jeweiligen fünfjährigen Altersgruppe an der jährlichen ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit in Kombination mit dem Bestand der gebärfähigen Altersgruppen ermittelt werden. Der Änderungsfaktor für die Entwicklung der Eheschliessungen wurde unter der Annahme ermittelt, dass sich das Verhältnis der verheirateten Frauen in allen Altersgruppen in gleichem Masse verändert wie der Gesamtbestand der weiblichen Bevölkerung. Diese Änderungsfaktoren werden für die Vorausberechnung anhand von drei hypothetischen Entwicklungsfällen zugrunde gelegt.

Entwicklungsfall eins: Die jährliche Zahl der ehelich Lebendgeborenen ist von 1925 bis 1975 konstant und gleich der Zahl der ehelich Lebendgeborenen im Jahr 1923.

Entwicklungsfall zwei: Die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit bleibt gleich der für den Durchschnitt der Jahre 1924 und 1925 berechneten Lebendgeborenenzahl unter Berücksichtigung der Lebendgeborenenzahl von 1923.

Entwicklungsfall drei: Die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit sinkt im Durchschnitt der Jahre 1924 und 1925 mit abnehmender Geschwindigkeit um insgesamt 25% bis 1955. In den Folgejahren bleibt die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit konstant.

Voraussichtliche Entwicklung der Geburten- und ehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsziffern 1925 bis 1975

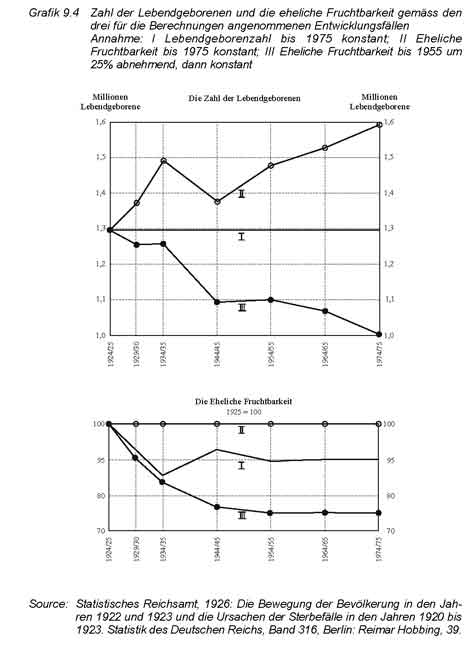

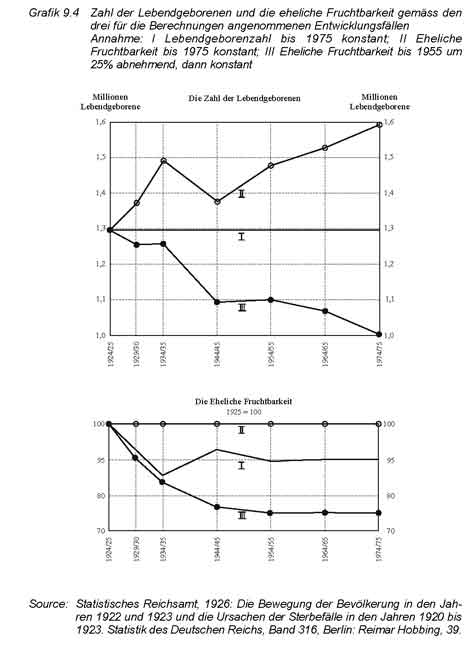

Die Ergebnisse der durchgeführten Vorausberechnung für die drei Entwicklungsfälle zeigen, wie der Kurvenverlauf der Lebendgeborenenzahl und ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit (siehe Grafik 9.4) von der Altersstruktur der weiblichen Bevölkerung im gebärfähigen Alter beeinflusst wird.

Der Kurvenverlauf für den ersten Entwicklungsfall zeigt, dass für die gleichbleibende Lebendgeborenenzahl von 1924/25 sogar eine niedrigere eheliche Fruchtbarkeit als im Jahr 1925 ausreichend ist. Im ersten Jahrzehnt sinkt die eheliche Fruchtbarkeitsziffer um 14,4% gegenüber dem Ausgangswert von 1924/25. Im zweiten Jahrzehnt steigt die eheliche Fruchtbarkeitsziffer mit dem Aufrücken der geburtenschwachen Geburtsjahrgänge in die Altersgruppen mit der “höchsten Fruchtbarkeit” bis auf 92,8% des Ausgangswerts von 1924/25 an. Dann nährt sich der Kurvenverlauf einem Wert, der unter 10% der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit des Jahres 1924/25 liegt.

Besonders deutlich zeigt sich der Einfluss der Struktur der weiblichen Bevölkerung auf den Kurvenverlauf im zweiten Entwicklungsfall. Die Konstanz der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit ist im ersten Jahrzehnt noch gewährleistet. Im zweiten Jahrzehnt zeigen sich Veränderungen in der Lebendgeborenezahl, die durch den Eintritt der geburtenschwachen Jahrgänge von 1915/19 verursacht werden. In diesem Jahrzehnt sinkt die jährliche Zahl der Lebendgeborenen um ca. 100.000 ab.

Im dritten Entwicklungsfall zeigt sich auffällig deutlich, wie stark die Entwicklung der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit vom Bestand der gebärfähigen Frauen abhängt. Der Kurvenverlauf der jährlichen Geborenenzahl zeigt ab dem zweiten Jahrzehnt eine scharfe Abnahme. Diese Abnahme wird sowohl durch den ehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsrückgang als auch durch das Aufrücken der zahlenmässig schwächer besetzten Geburtsjahrgänge 1915/19 in die Altersgruppen mit der “höchsten Fruchtbarkeit” verursacht. Die Abwärtsbewegung der Geborenenzahl hält auch nach 1955, trotz der angenommenen Konstanz der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit in den nachfolgenden Jahren weiter an, “weil die Zahl der im gebährfähigen Alter stehenden Frauen ständig zurückgeht.” (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 1926, Richtlinien, 39).

Voraussichtliche Entwicklung der Gesamtbevölkerung und der Bevölkerungsstruktur 1925 bis 1975

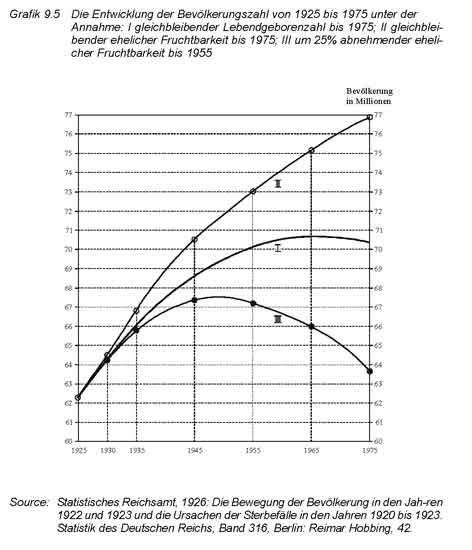

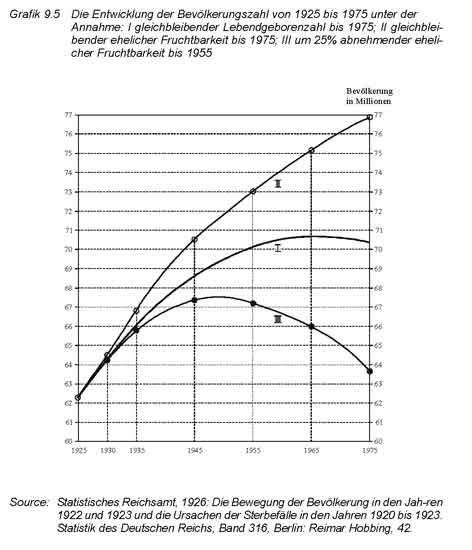

Wie sich im Berechnungszeitraum die Gesamtbevölkerung und die Bevölkerungsstruktur entwickeln wird, zeigen die nachfolgenden Kurvenverläufe (siehe Grafik 9.5).

Im ersten Entwicklungsfall, der konstante Geburtenzahl für den gesamten Berechnungszeitraum unterstellt, wächst die Bevölkerung bis 1965 auf ca. 70,7 Millionen an, dargestellt im Verlauf der Kurve I. Im weiteren Verlauf verringert sich das Wachstum der Gesamtbevölkerung und entwickelt sich langfristig zu zu einer stationären Bevölkerung.10 In den anschliessenden Jahren nähert sich diese “Gesamtbevölkerung mit ständig geringer werdender Geschwindigkeit einer konstanten Zahl von 69,3 Millionen” an (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 1926, Richtlinien, 42). Unter diesen Umständen wird sich die Altersstruktur langfristig verändern. Während die Zahl der unter 15jährigen im Untersuchungszeitraum nahezu unverändert bleibt, wächst die Zahl der 15 bis unter 65jährigen zwischen 1925 und 1975 um ca. 7% an. Noch bedeutsamer werden die Veränderungen bei den über 65jährigen sein, deren zahlenmässiger Bestand innerhalb der 50 Jahre um mehr als 200% wachsen wird. (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 1926, Richtlinien, 45).

Im zweiten Entwicklungsfall, konstante eheliche Fruchtbarkeit in allen Altersgruppen für den gesamten Berechnungszeitraum, steigt die Bevölkerungszahl ständig an. Die Bevölkerung nimmt im Verlauf von 50 Jahren um 14,6 Millionen zu. Sie wird bis zum Jahr 1975 auf 76,9 Millionen anwachsen. Auch nach 1975 wird die Bevölkerung, weiter anwachsen “wenn auch mit allmählich verzögerter Geschwindigkeit.” (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 1926, Richtlinien, 42). Hinsichtlich des Altersaufbaus treten die Veränderungen sowohl bei der zahlenmässigen Besetzung der unter 15jährigen als auch der 15 bis unter 65jährigen Altersgruppen zwischen 1925 und 1975 auf. Gegenüber dem ersten Entwicklungsfall nimmt der zahlenmässige Bestand der 15 bis unter 65jährigen im gleichen Zeitraum um ca. 9,2% zu. Ebenso fällt der zahlenmässige Zuwachs der über 65jährigen besonders stark aus. Deren Zahl wird sich im Untersuchungszeitraum verdoppeln (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 1926, Richtlinien, 45).

Im Unterschied hierzu zeigt der dritte Entwicklungsfall, der sukzessive eheliche Fruchtbarkeitsrückgang um 25% im Laufe von 25 Jahren, ein sehr viel differenziertes Bild über die Entwicklung der Gesamtbevölkerung. Bis 1955 wird demnach die Bevölkerung um knapp 3,8 Millionen anwachsen und in den folgenden Jahrzehnten beständig wieder abnehmen. Erwartet wird, dass sich diese Entwicklung auch über das Jahr 1975 weiter fortsetzt und damit die demografischen Prozesse langfristig prägen wird. Diese Tatsache wird durch die ungleichmässige Verteilung der Altersgruppen im Altersaufbau belegt. Durch den nach dem Erstem Weltkrieg sich fortsetzenden Geburtenund ehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsrückgang wird die zahlenmässige Besetzung der unter 15jährigen sich deutlich verringern. Im dritten Entwicklungsfall wird der zahlenmässige Bestand der über 65jährigen noch rascher zunehmen (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 1926, Richtlinien, 45).

Beim Vergleich der Entwicklungsvarianten fällt auf, dass die Bevölkerung nach allen drei Entwicklungsfällen von 1925 bis 1945 wachsen wird.11 Dieses Bevölkerungswachstum erklärt sich zu nicht geringen Teilen aus der Sterblichkeitsentwicklung, die in den Jahren 1924/26 besonders günstig war. Sie ist geprägt durch besonders niedrige altersspezifische Sterblichkeitsziffern bei Männern und Frauen.12 Sie führen zu einem leichten Anstieg der Lebenserwartung und der Zunahme der Gesamtbevölkerung. Die Rechnungen für den zweiten und dritten Entwicklungsfall belegen die schwache Besetzung der Geburtenjahrgänge nach 1935. Gleichzeitig rücken in den Folgejahren die geburtenstarken Vorkriegsjahrgänge in die höheren Altersgruppen auf.

Diese Erscheinung kennzeichnet ab 1965 die Entwicklung einer schwächeren Geburtendynamik und eine anwachsende Sterblichkeit. Vor allem die Berechnungen des dritten Entwicklungsfalls weisen auf die neuen demografischen Herausforderungen für die sozialen Sicherungssysteme hin: Einerseits der Geburtenrückgang und andererseits die Alterung der Bevölkerung.13

Langfristig zeigt sich eine “allmähliche Überalterung der Bevölkerung” und die hieraus erwachsenden “allgemeinen Versorgungslasten durch die Veränderungen des Zahlenverhältnisses der Nichterwerbstätigen (Kinder, Ehefrauen, Greise) zu den Erwerbstätigen.” (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1926: Richtlinien, 47).

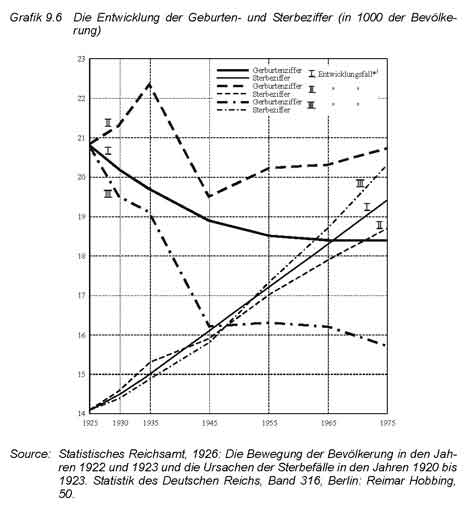

Voraussichtliche Tendenzen in der Entwicklung des Geburtenund Sterbefallüberschusses

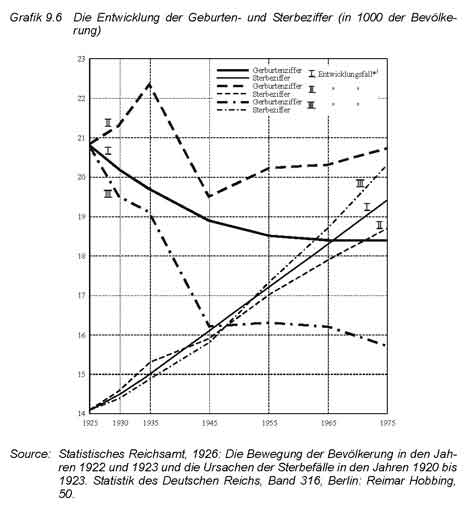

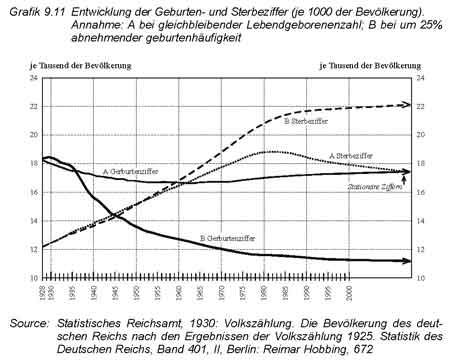

Um die Ergebnisse der Bevölkerungsdynamik in Verbindung mit der Altersstruktur zu überprüfen, werden noch einmal die Geburten- und Sterbeziffern siehe Grafik 9.6) auf Grundlage der drei Entwicklungsfälle berechnet. Hieran ist die Frage geknüpft, wie sich langfristig die Geburten- und (oder) Sterbefallüberschüsse im Prozess der Bevölkerungsalterung entwickeln und die Bevölkerungsdynamik beeinflüssen werden.

Beim ersten Entwicklungsfall sinkt die Geburtenziffer von 1925 bis 1965 und gleichzeitig steigt die Sterbeziffer, ausgelöst durch die Verschiebungen im Altersaufbau der Bevölkerung, an. Nach 1965 wandelt sich der Geburten- in einen Sterbefallüberschuss und in der Konsequenz gestaltet sich das Bevölkerungswachstum, trotz der jährlich gleichbleibenden Geburtenzahl, negativ.

Im zweiten Entwicklungsfall nimmt zunächst im ersten Jahrzehnt die Geburtenziffer zu und fällt bis 1945 stark ab. Von 1945 bis 1975 steigt die Geburtenziffer mit leichten Schwankungen um ca. 6% und die Sterbeziffer um ca. 32,6% zwischen 1925 und 1975 an. Ungeachtet dieser unterschiedlichen Bewegung der Geburten- und Sterbeziffer wird die gesamte Untersuchungsperiode durch einen Geburtenüberschuss bestimmt. Obwohl letzterer zeitweilig zunimmt und nach 1945 sich wieder verringert, wächst nach diesem Entwicklungsfall die Bevölkerung ständig im gesamten Untersuchungszeitraum, allerdings mit nachlassender Intensität.

Beim dritten Entwicklungsfall kommt es bereits in den ersten zwei Jahrzehnten zwischen 1925 und 1945 zu “einem Absturz der Geburtenziffer”. (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1926, Richtlinien, 50). Auf diesem Niveau verbleibt die Geburtenziffer weitere 20 Jahre, um dann erneut, aber mit nachlassender Intensität, zu sinken. Der starke Abfall der Geburtenziffern bewirkt bereits 1945 ein Zusammentreffen mit den ansteigenden Sterbeziffern, ausgelöst durch die Verschiebungen der Altersstruktur und die Überalterung der Bevölkerung. In allen drei Entwicklungsfällen zeigt der Kurvenverlauf der allgemeinen Sterblichkeit einen recht geradlinigen Anstieg infolge der zunehmenden Besetzung der höheren Altersgruppen.

Die zweite amtliche Vorausberechnung von 1930

In der zweiten Vorausberechnung rücken die Veränderungen der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit in den Nachkriegsjahren in den Vordergrund der Analysen und Berechnungen. Die Veränderungen zeigen sich in der rückläufigen Geburten- und Fruchtbarkeitsentwicklung, die nach Ansicht der amtlichen Statistik auf “den bewussten Willen zur Einschränkung der Kinderaufzucht” zurückzuführen ist (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Bd. 401, II, Ausblick, 442). Dieser Umstand wird mit der Frage verknüpft, wie sich künftig das eheliche Fruchtbarkeitsverhalten entwickeln und welche Ausmasse es auf die Bevölkerungsdynamik haben wird. Zur Beurteilung der künftigen Bevölkerungsentwicklung wird ein Berechnungsmodell zur Begründung der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit und der Reproduktionsintensität des weiblichen Bevölkerungsteils gewählt.

Untersucht werden einerseits die strukturellen Veränderungen der weiblichen Bevölkerung im fertilen Alter und andererseits deren verändertes Fortpflanzungsverhalten. Berücksichtigt werden hierbei die Veränderungen der Eheschliessungsquoten. Die amtliche Statistik wirft in diesem Zusammenhang die Frage auf, ob unter den Bedingungen der Bestandsveränderungen der fertilen weiblichen Bevölkerung und deren verändertem Fruchtbarkeitsverhalten wellenartige Geburtenausfälle entstehen werden.

Analysiert und berechnet werden die Verschiebungen in der Altersstruktur der Gesamtbevölkerung und hierbei vor allem die Verschiebungen im Ehebestand und im Bestand der fortpflanzungsfähigen weiblichen Bevölkerung. Für diese Vorausberechnung des Bevölkerungsbestandes wird wiederum die

Komponentenmethode angewandt.

Für die Berechnung der Absterbeordnung wurde eine neue Sterbetafel für die Jahre 1924/26 ausgearbeitet und die altersspezifíschen Sterblichkeitsziffern als konstant angenommem. Von vornherein werden die Aus- und Einwanderungsbewegungen aus den Berechnungen ausgeschaltet. Als massgebliche Einflusskomponente, die den Verlauf der künftigen Bevölkerungsentwicklung bestimmt, wird das veränderte individuelle eheliche Fruchtbarkeitsverhalten in Betracht gezogen.

Für die Vorausberechnungen der Geburten- und ehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsentwicklung werden zwei hypothetische Entwicklungsfälle formuliert.

Entwicklungsfall A: Die jährliche Geborenenzahl der Lebendgeborenen bleibt ständig gleich der Lebendgeborenenzahl des Jahres 1927.

Entwicklungsfall B: Die eheliche und uneheliche Fruchtbarkeit nimmt gegenüber dem Stand von 1927 um insgesamt 25% bis zum 1955 ab.

Der Entwicklungsfall A entspricht theoretisch der Ausbildung einer stationären Bevölkerung während der Entwicklungsfall B die nachlassende ehelichen Geburtenhäufigkeit in den Jahren 1922 bis 1927 berücksichtigt, die an Hand von mehreren Berechnungsmethoden ermittelt wird.

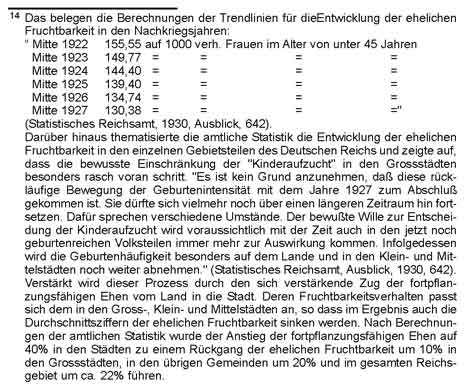

Ermittelt wird eine Trendlinie der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit für die Gesamtheit der fertilen weiblichen Bevölkerung im Zeitraum 1922 bis 1927. Um Struktureffekte wie die unterschiedliche Besetzung in den fertilen weiblichen Altersgruppen oder Schwankungen in der wirtschaftlichen Konjunkturentwicklung auszuschliessen, werden standardisierte Fruchtbarkeitsziffern gebildet (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, Bewegung, 26ff.). Hieran schliessen sich Berechnungen der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsziffern für das Jahr 1927 an. Die Berechnungsergebnisse werden an die Werte der Trendlinien angepasst und eine Messziffer für die Jahre 1927-1955 gebildet. Für die weiteren Jahre wird diese Berechnung in einem Intervall von 15 Jahren fortgesetzt. Die Berechnungen der amtlichen Statistik bestätigten die Annahme, dass das nachlassende individuelle Fruchtbarkeitsverhalten der fertilen weiblichen Bevölkerung

die wesentliche Ursache für die abnehmende Geburtenintensität bildet.14 Die Erhebungen der amtlichen Statistik zeigen, dass erste Veränderungen in der Geburtenentwicklung bereits in den Vorkriegsjahren eingetreten sind.

Diese bildeten eine wesentliche Quelle für die Diskussionen in den Nachkriegsjahren um die Ursachen, den Verlauf und die Konsequenzen der abnehmenden ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit für die Bevölkerungsentwicklung und -struktur.

Thematisiert wurden die ökonomischen und sozialen Veränderungen, die dem Rückgang der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit voraus gingen, von Vertretern der Nationalökonomie, Statistik und Sozialhygiene. Zu ihnen zählen u.a. Ludwig Josef Brentano (1844-1931), Julius Wolf (1862-1937), Alfred Grotjahn (1869-1931), Paul Mombert (1876-1938) u.v.a.m.

Als weiterer Faktor, der den Verlauf der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit beinflusst, wurde die Verheiratetenquote der Frauen im gebärfähigem Alter ermittelt.15

Um die Differenz zwischen den erwartungsmässigen und den tatsächlichen Eheschliessungen jedes Alters in den Jahren 1924 bis 1927 berechnen zu können, wurden zunächst standardisierte Altersheiratsziffern für die männliche Bevölkerung, bezogen auf die Heiratshäufigkeit der Jahre 1910/11, berechnet. Die Ermittlung der Heiratsziffer für ledige Männer war notwendig, um die Eheschliessungsmöglichkeiten der Frauen, deren zahlenmässiger Bestand einen Überschuss aufweist, zum Ausdruck zu bringen.16 Von 1928 bis 1940 zeigen die Berechnungen eine Zunahme der Verheiratetenquoten der unter 45jährigen Frauen und der unter 48jährigen Männer. Infolge

der Verringerung der Sterblichkeit vor allem auf seiten der männlichen Bevölkerung rechnet die amtliche Statistik nach 1940 mit einem Männerüberschuss in den Altersgruppen mit der höchsten Heiratshäufigkeit. Um den Einfluss der Heiratshäufigkeit auf die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit und das Fruchtbarkeitsverhalten

berechnen zu können, wurde die Gesamtheit der verheirateten Frauen nach der Ehedauer zusammengestellt und in Beziehung mit der Ordnungszahl der Erst-, Zweit-, Dritt-, Viert- und weiterer Geburten gebracht. 17

Hierzu wurden standardisierte Fruchtbarkeitsziffern für die fünfjährigen Altersgruppen der gebärfähigen Frauen, gegliedert nach der Parität der Geburten für die Jahre 1922 bis 1927, berechnet. Die Berechnungen zeigten vor allem einen Rückgang der Erst- und Zweitgeburten. Hieraus leitete die amtliche Statistik ihre Annahme ab, dass der Geburten- und Fruchtbarkeitsrückgang vor allem auf das Verhalten der Familien, die Zahl der Kinder möglichst klein zu halten, zurückzuführen sei.

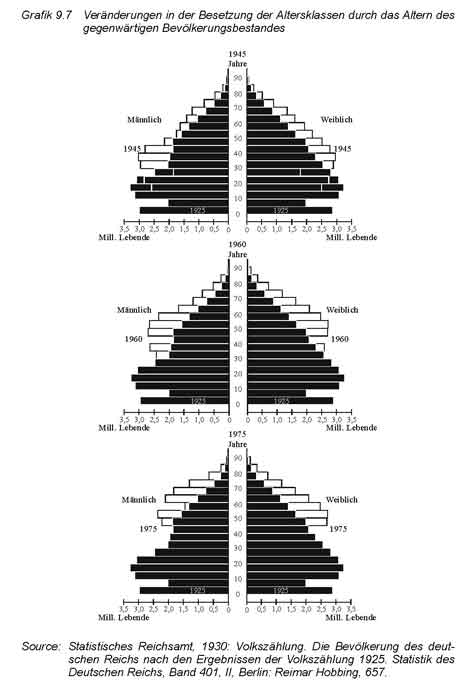

Zukünftige Veränderungen im Altersaufbau unter Berücksichtigung der Sterblichkeitsverhältnisse von 1924/26

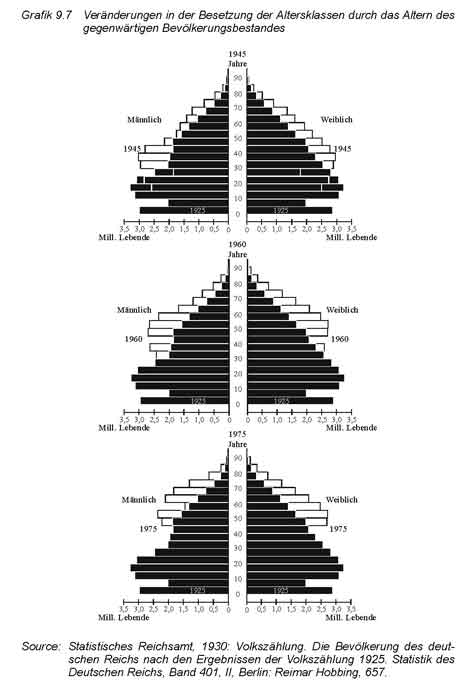

Auf Basis der Sterbetafel von 1924/26 wurden altersspezifische Sterblichkeitsziffern berechnet und mit dem nach der Volkszählung von 1925 ermittelten Altersaufbau in Beziehung gesetzt. Wie sich der Altersaufbau im Zeitverlauf verändern wird, demonstriert die nachfolgende Grafik (siehe Grafik 9.7).

Festgestellt wird eine verhältnismässig starke Besetzung der über 20jährigen im Jahre 1930. Sie sind auf die starken Geburtenjahrgänge von 1905 bis 1909 zurückzuführen. Diese verhältnismässig starke Besetzung wird sich unter Berücksichtigung gleichbleibender Sterblichkeitsverhältnisse in die höheren Altersgruppen verschieben. Mit dem Aufrücken dieser Geburtenjahrgänge in die alten und älteren Altersgruppen wächst deren Bestand zusehends an: “Bei den über 80jährigen schliesslich erstreckt sich die Zunahme voraussichtlich sogar bis 1990. Um diese Zeit werden rechnungsmässig etwa 4 bis 5mal so viel Personen dieses Alters vorhanden sein, wie bei der Volkszählung im Jahre 1925”. (Statistisches Reichsamt, Ausblick, 1930, 642).

Ein diametral entgegengesetztes Bild zeigt sich bei den geburtenschwachen Jahrgängen der Jahre 1914 bis 1919 und deren Vorrücken in die mittleren Altersgruppen. Sie führen zu einer deutlich geringen Besetzung der 25 bis unter 30jährigen im Jahr 1945 bzw. der 45 bis unter 50jährigen im Jahr 1960.

Diese Einschnitte in der Altersstruktur durch die schwach besetzten Geburtenjahrgänge zwischen 1915 und 1919 werden zwar z. T. durch die stärker besetzten Geburtenjahrgänge der ersten Nachkriegsjahre wieder ausgeglichen, ohne jedoch das Niveau der Vorkriegsjahre noch einmal zu erreichen.

Im Gegenteil führen sie wiederum zu neuerlichen Veränderungen in der Besetzung der unteren Altersgruppen der 15 bis unter 20jährigen im Jahr 1945, der 30 bis unter 35jährigen im Jahr 1960 bzw. 45 bis unter 50jährigen im Jahr 1975. Geschlussfolgert wird, dass die im Ergebnis des Ersten Weltkrieges entstandenen Verschiebungen in der Alters- und Geschlechtsstruktur sich zukünftig wellenförmig fortsetzen und damit auch die künftige Entwicklung der Eheschliessungen und der ehelichen Fortpflanzung beeinflussen werden.

Die Verschiebungen in der Alters- und Geschlechtsstruktur zeigen sich beispielsweise bei der Entwicklung des Ehebestandes. So führt der Frauenüberschuss in den 25 bis unter 50jährigen Altersgruppen zu einer Zunahme der Eheschliessungen in den mittleren Altersgruppen. Es wird in diesem Zusammenhang auf die Zunahme des Anteils der “Spätehen” verwiesen, deren durchschnittliche Kinderzahl durch die verhältnismässig späte Eheschliessung “naturgemäss” kleiner ausfallen wird.

Mit dem Aufrücken der schwach besetzten Geburtenjahrgänge der Kriegsjahre in die Jahrgänge mit der höchsten Heiratshäufigkeit und dem Herausbilden eines Männerüberschusses bei den 20 bis unter 30jährigen Männern wird die Zahl der Frühehen wieder zunehmen. Dieser zeitweilige Anstieg des Ehebestandes, vor allem der “jungen Ehen”, wird um das Jahr 1940 abgeschlossen sein. Mit dem Aufrücken der geburtenschwachen Nachkriegsjahrgänge in die Altersgruppen mit der höchsten Heiratshäufigkeit werden nach 1940 vor allem die weiblichen Altersgruppen im fertilen Alter nicht mehr voll besetzt sein. Diese rückläufige Besetzung kann nach Ansicht der amtlichen Statistik auch nicht durch eine höhere Geburtenhäufigkeit ausgeglichen werden.

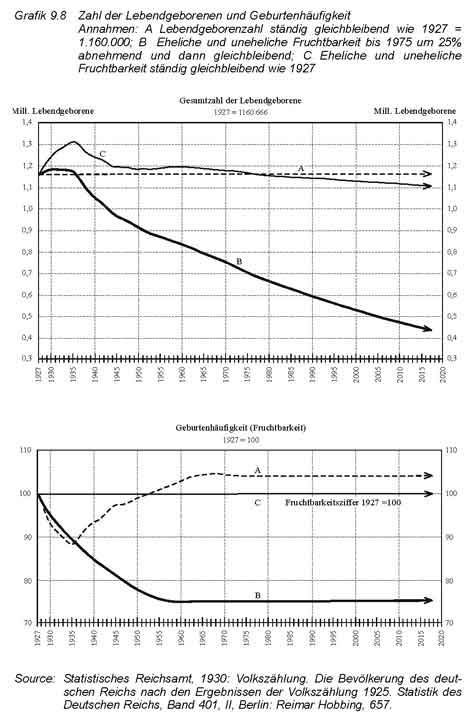

Voraussichtliche Entwicklung der Geburtenziffern und der ehelichen sowie unehelichen Fruchtbarkeit 1930 bis 2000

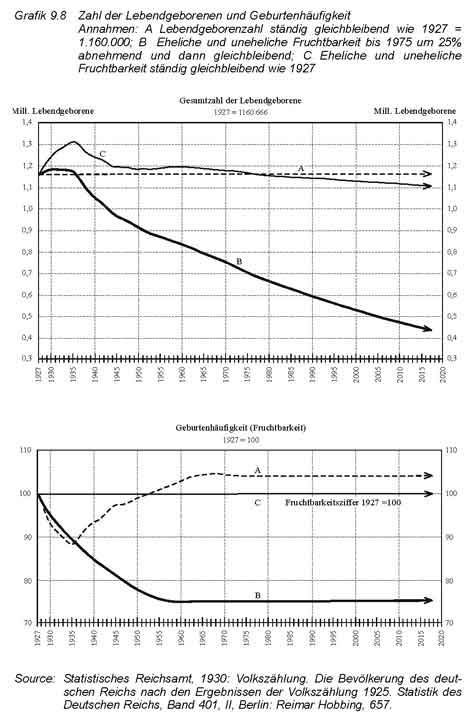

Die Berechnungen zur Entwicklung der Geborenenzahl und der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit sind anhand von drei Entwicklungsfällen durchgeführt worden. Neben dem Entwicklungsfall A (die jährliche Geborenenzahl der Lebendgeborenen bleibt ständig gleich der Lebendgeborenenzahl des Jahres 1927) und dem Entwicklungsfall B (die eheliche und uneheliche Fruchtbarkeit nimmt gegenüber dem Stand von 1927 um insgesamt 25% bis zum 1955 ab und bleibt danach unverändert), wird auch der Entwicklungsfall C (gleichbleibende Fruchtbarkeit wie 1924/25) in die Berechnungen aufgenommen (siehe Grafik 9.8).

Während die Zahl der Lebendgeborenen nach dem Entwicklungsfall A für den Zeitraum zwischen 1927 und 2000 sich nicht verändert, zeigen sich bei der Bewegung der Lebendgeborenen nach dem Entwicklungsfall C erste Abweichungen. Der zeitweilige Anstieg der Lebendgeborenenzahl nach 1927 ist z. T. auf das Nachholen von ausgefallenen Geburten in den Kriegs- und ersten Nachkriegsjahren zurückzuführen. Die geburtenschwachen Jahrgänge 1915 bis 1919 leiten ca. 20 Jahre später den Rückgang der Geborenen zahl zwischen 1935 bis 1945 ein. Diese Tendenzen setzen sich auch im Zeit verlauf weiter fort.18

Auffallend ist die Bewegung der Zahl der Lebendgeborenen nach dem Entwicklungsfall B, die zwischen 1927 und 1931 leicht ansteigt. Dieser Anstieg ist wiederum z. T. auf das Nachholen von ausgefallen Eheschliessungen und Geburten in den Kriegs- und Nachkriegsjahren zurückzuführen. Der Eintritt der geburtenschwachen Jahrgänge 1915 bis 1919 in die Altersgruppe der 20 bis 25jährigen führt unweigerlich zu einer Abnahme der Geborenzahl, der sich durch den Rückgang der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit weiter verstärkt. Diese Tendenz der abnehmenden Geburtenzahl wird sich auch nach 1955 weiter fortsetzen.19

Ein anders Bild ergeben die Kurvenverläufe des Entwicklungsfalls A zur Bewegung der Geborenenzahl und des Entwicklungsfalls B zur Bewegung der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit zwischen 1927 und 2000. Nach dem Entwicklungsfall A sinkt bis 1935 die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit im gleichen Masse wie die Lebendgeborenenzahl bei konstanter ehelicher Fruchtbarkeit ansteigt.

Die Symmetrie zwischen den beiden Kurven wird aufgehoben, “wenn die nach 1927 geborenen Jahrgänge, die bei konstanter Geburtenzahl schwächer besetzt sind als bei konstanter ehelicher Fruchtbarkeit, in das fertile Alter eintreten”. (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, Ausblick, 662). Etwa um das Jahr 1955 hat dann die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit wieder das Ausgangsniveau von 1927 erreicht. Ab 1965 wird bis zum Jahr 2000 das Ausgangsniveau der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit von 1927 um ca. 4% überschritten. Diese Ergebnisse setzen allerdings den Anstieg der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit über das Niveau des Jahres 1927 voraus.

Notwendigerweise führt der Entwicklungsfall B, durch den in Rechnung gestellten Rückgang der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit um 25% bis 1955, zu einem Rückgang der Geburtenhäufigkeit und zum anderem zu strukturellen Veränderungen durch den Eintritt der geburtenschwachen Kriegsjahrgänge in die Altersgruppe der 20 bis unter 30jährigen. Auch in den nachfolgenden Jahrzehnten setzt sich diese Entwicklung weiter fort, weil “die nunmehr in das gebärfähige Alter eintretenden Jahrgänge …. zahlenmässig immer schwächer werden” (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, Ausblick, 662).

Die Gegenüberstellung der Kurvenverläufe für die Zahl der Geborenen und der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit zeigen, dass bereits 1927 das Niveau der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit zu niedrig war, um die jährliche Zahl von 1.160.000 Geburten dauerhaft aufrecht zu erhalten. In der Konsequenz führt das zu niedrigere Niveau der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit zu wellenartigen Geburtenausfällen.

Voraussichtliche Entwicklung der Gesamtbevölkerung und des Geburten- bzw. Sterbefallüberschusses 1927 bis 2000

Für die Berechnungen der voraussichtliche Entwicklung der Gesamtbevölkerung und des Geburten- bzw. Sterbefallüberschusses 1927 bis 2000 werden wiederum die drei Entwicklungsfälle, die auch bei den Berechnungen der Geburtenziffern und der ehelichen sowie unehelichen Fruchtbarkeit angewandt werden, zugrunde gelegt (siehe Grafik 9.9).20

Bereits der Entwicklungsfall A zeigt einschneidende Veränderungen des Geburtenüberschusses in der Gesamtbevölkerung bis zum Jahr 2000 und darüber hinaus. Die allmähliche Verringerung des Geburtenüberschusses beginnt bereits 1927 und setzt sich bis zum Beginn der 1960er Jahre fort. Verursacht wird diese Entwicklung durch die Veränderungen der Bevölkerungsstruktur, vor allem durch das Aufrücken der geburtenstarken Vorkriegsjahrgänge in die höheren Altersgruppen. Nach 1961/62 wird der Geburtendurch einen Sterbefallüberschuss abgelöst. Diese Tendenzen widerspiegeln sich in der Entwicklung der Gesamtbevölkerung. Zwischen 1927 und 1960 wird nach dem Entwicklungsfall A die Gesamtbevölkerung noch leicht um ca. 10% wachsen. Für die nachfolgenden Jahrzehnte zeichnet sich allerdings bereits ein Bevölkerungsrückgang mit nachlassender Intensität ab, der sich auch nach dem Übergang in das 21. Jahrhundert weiter fortsetzen wird.

Auch im Entwicklungsfall B wird sich von Beginn der Untersuchungsperiode an der Geburtenüberschuss verringern. Der Wechsel vom Geburten- zum Sterbeüberschuss wird sich allerdings im Vergleich zum Entwicklungsfall A sehr viel früher, um das Jahr 1945, vollziehen. Der schnelle Wechsel vom Geburten- zum Sterbefallüberschuss findet seine Entsprechung in der Entwicklung der Alters- und Geschlechtsstruktur. Der zeitweilige Anstieg der Gesamtbevölkerung fällt mit der verhältnismässig starken Besetzung der Geburtsjahrgänge 1909/11 der weiblichen Bevölkerung und deren Eintritt in die fortpflanzungsstärksten Altersgruppen zusammen. Allerdings bestimmen sie die Entwicklung der Gesamtbevölkerung nur bis 1935. In den nachfolgenden Jahren wird es durch die abnehmende Besetzung der weiblichen Bevölkerung und des ehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsrückgangs zu einem permanenten Bevölkerungsrückgang kommen. Nach 1945 wird sich dieser Bevölkerungsrückgang weiter beschleunigen und selbst unter Berücksichtigung des Entwicklungsfalls B, eine gleichbleibende bzw. “unveränderte Geburtenhäufigkeit” nach 1955, kann diese Tendenz sich bis “ins Endlose fortsetzen.” (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, Ausblick, 664).

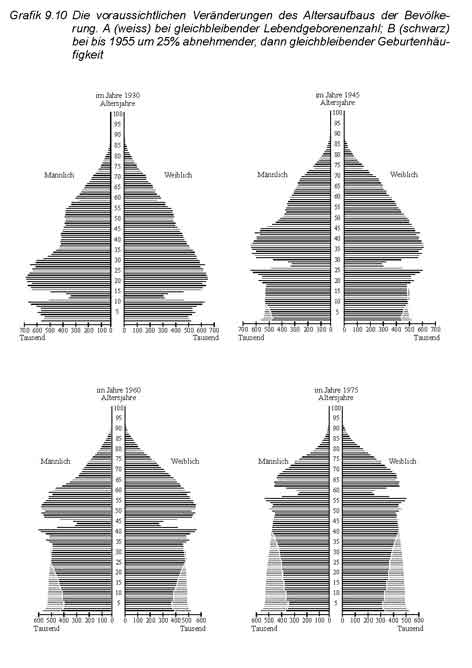

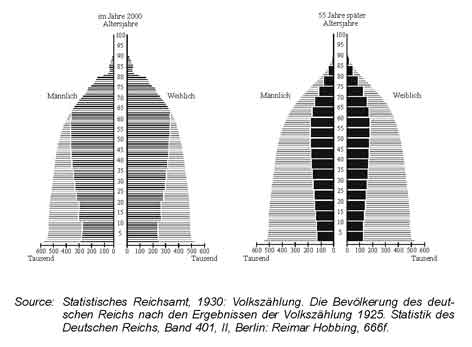

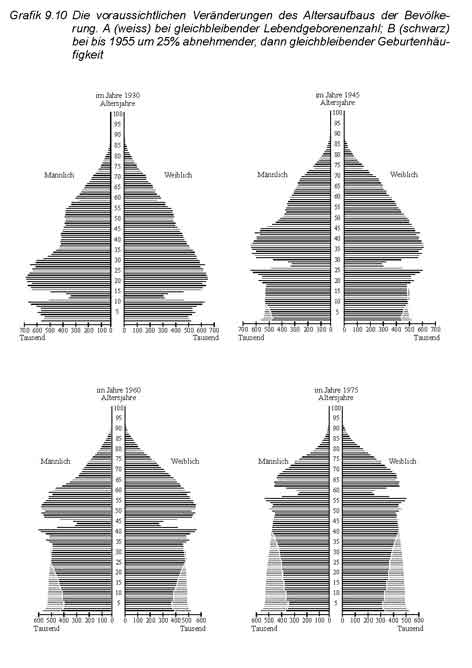

Auf lange Sicht werden diese aufgezeigten Entwicklungstendenzen zu bedeutsamen Veränderungen der Alters- und Geschlechtsgliederung führen, wie die Darstellungen der Veränderungen im Altersaufbau der Bevölkerung des Deutschen Reichs von 1930 bis 2055 belegen (siehe Grafik 9.10).

Nach dem Entwicklungsfall A werden die unteren Altersgruppen nicht mehr voll besetzt sein, weil die eheliche Fruchtbarkeit zur Aufrechterhaltung der jährlichen Zahl der Lebendgeborenen bereits zu niedrig ist. Die durch den Ersten Weltkrieg hervorgerufenen Störungen in der Altersstruktur rücken im Zeitverlauf in die höheren Altersgruppen. Im Ergebnis entsteht ein neuer Altersaufbau, der durch eine verhältnismässig gleiche Besetzung in allen Altersgruppen charakterisiert ist. Dieser Prozess, die Entstehung einer stationären Bevölkerung, wird nach den Berechnungen der amtlichen Statistik um das Jahr 2000 abgeschlossen sein.

Nach dem Entwicklungsfall B wird sich im Untersuchungszeitraum die zahlenmässige Besetzung der unteren Altersgruppen permanent verringern. Durch die ununterbrochene Abnahme der Geburtenzahl ist jede Altersgruppe schwächer besetzt als die nächst höhere Altersgruppe. In Folge bildet sich ein neuer Altersaufbau, mit “einer nach unten hin sich verjüngenden Urne”, deren Basis immer schmaler wird, heraus (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, Ausblick, 665).

Gemeinsam ist den verschiedenen Formen des Altersaufbaus nach den Entwicklungsfällen A und B eine Alterung der Gesamtbevölkerung. Sie führt in der Konsequenz zu einer stärkeren Besetzung in den höheren und hohen Altersgruppen. Vor allem die Berechnungen auf der Grundlage des Entwicklungsfalls B belegen eine besonders schnelle Zunahme in den Altersgruppen der über 60jährigen, die sich im Vergleich zum Entwicklungsfall A wesentlich dynamischer gestaltet: “Der Anteil der 70 bis 80jährigen an der Gesamtbevölkerung steigt auf das 31/4fache an, während die Gruppe der Kinder und Jugendlichen bis Ende des Jahrhunderts auf 2/3 ihres jetzigen Bevölkerungsanteil zusammenschrumpft.” (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, Ausblick, 645).

Die Bevölkerungsmodelle mit stabilen Altersstrukturen

Die zwei unterschiedlichen Formen des Altersaufbaus, die sich unter Berücksichtigung der zwei Entwicklungsfälle bis zum Jahr 2055 herausbilden werden, weisen auf ein wichtiges demografisches Phänomen, die Überalterung der Bevölkerung, hin. Ein Indikator, der die Bevölkerungsalterung widerspiegelt ist das mittlere Alter einer Bevölkerung. Die Veränderungen des mittleren Alters der Bevölkerung berechnet die amtliche Statistik auf Grundlage des Entwicklungsfalls A (gleichbleibende Lebendgeborenenzahl wie 1927) und Entwicklungsfalls B (bis 1955 um 25% abnehmende und danach gleichbleibende Geburtenhäufigkeit). Im Entwicklungsfall A steigt das mittlerer Alter der Bevölkerung bis zum Jahr 2000 um 5 Jahre und im Entwicklungsfall B um 14 Jahre an. Die Verschiebungen im Altersaufbau und die Zunahme des mittleren Alters der Bevölkerung deuten bereits langfristige Veränderungen in der Entwicklung der Bevölkerungsdynamik an.

Um diese langfristigen Veränderungen der Bevölkerungsdynamik zu quantifizieren, werden für die weiteren Berechnungen die Modelle der stationären und stabilen Bevölkerung zugrunde gelegt. Gefragt wird erstens, wie hoch der tatsächliche Geburtenüberschuss unabhängig von dem Altersaufbau der Bevölkerung noch ist. Gefragt wird zweitens, wie sich die Bevölkerungsdynamik nach dem Entwicklungsfall B langfristig gestalten wird.21

Zu diesem Zweck werden weitere Berechnungen anhand des stationären und stabilen Bevölkerungsmodells, die in ihren Grundzügen vom österreichischen Populationstheoretiker Alfred J. Lotka (1880-1949) in den 1920er Jahren entwickelt worden war, durchgeführt.22 Bei der Vorgehensweise beruft sich die amtliche Statistik auf die Methodik von Lotka zur Berechnung der NRR und berechnet den Annäherungswert J. Für alle drei Enwicklungsvarianten wurden zunächst die Werte der allgemeinen Fruchtbarkeitsziffern für fünfjährigen Altersgruppen sowie für Mädchengeburten aus der Trendlinie

des Jahres 1927 berechnet. Als weitere Komponente wurde die Verheiratetequote je Frau jeden Alters vom Jahre 1975 als gleichbleidend für alle drei Entwicklungsfälle in die Berechnungen integriert. Unter der Maßgabe der gleichbleibenden alterspezifischen Sterblichkeit und der berechneten allgemeinen

Fruchtbarkeitsziffern für Mädchengeburten wurde mit Hilfe von Integralableitungen die Ziffer für den Wert J berechnet, der die Überlebenswahrscheinlichkeit des weiblichen Geschlechts einer Frauenkohorte nach der Sterbetafel 1924/26 zum Ausdruck bringt. Der Wert J wird hier als Ersatzwert für die NRR genommen und lässt sich als die Zahl von 100 000 Mädchengeburten, die das fertile Alter einer Frauenkohorte erreichen und durchleben in Kombination mit der Fruchtbarkeit der fünfjährigen Altersgruppen, interpretieren.23

Unter den Bedingungen der stabilen Bevölkerung bei gleichbleibender Geburtenhäufigkeit wie 1927 ergab der Wert J, dass die Überlebenden von 100 00 lebenden Mädchengeburten bei den zu Grundlage genommenen allgemeinen Fruchtbarkeitsziffern 3,78% weniger Mädchen gebären werden als zur Erhalt des Bevölkerungsbestandes notwendig ist. Die durchschnittliche jährliche Zahl der Lebendgeborenen nimmt auf Grund der weiteren Veränderungen im Bestand der Frauen in den fertilen Altersgruppen von Jahrfünft zu Jahrfünft ab. Nach Überwindung der ungleichmässigen Besetzung der Altersgruppen durch den gegenwärtigen Altersaufbau wird die stabile Bevölkerung bei gleichbleibenden Geburtenhäufigkeit wie 1927 und konstanter altersspezifischer Sterblichkeit ein jährliches Geburtendefizit von -1,34‰ der mittleren Bevölkerung aufweisen.

Nach den Berechnung der ständig gleichbleibender Lebendgeborenenzahl wie 1927 ( Entwicklungsfall A ) entsteht eine sationäre Bevölkerung. Zur Bildung der stationären Bevölkerung kommt es, nach dem die skizzierten Unregelmässigkeiten im Altersaufbau langfristig überwunden werden. Der Wert J ist dann gleich 1. Dies wiederum setzt voraus, dass die Geburtenhäufigkeit der Mädchengeburten ständig gleich bleibt, d.h. die Überlebenden von je 100.000 geborenen Mädchen im gebärfähigen Alter immer wieder 100.000 Mädchen zur Welt bringen. Die Fruchtbarkeit von 1927 müsste daher um 3,93% grösser sein, um den Wert von J=1 zu erreichen. Den Berechnungen nach war bereits im Ausgangsjahr 1927 die Geburtenhäufigkeit zu niedrig, um die jährlich gleichbleibende Lebendgeborenenzahl wie im Jahre 1927 konstant zu halten.

Im Entwicklungsfall B wird angenommen, dass neben den ehelichen und unehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsziffern bei gleichen Verheiratetenquoten und die allgemeinen Fruchtbarkeitsziffern bis 1955 um 25% abnehmen und auf diesem niedrigeren Niveau in den Folgejahrzehnten sich nicht verändern. Die stabile Bevölkerung, die bei einer ab 1955 gleichbleibenden, um 25% niedrigeren Fruchtbarkeit und unveränderten Sterblichkeitsverhältnissen entstehen wird, zeigt eine Zunahme des Defizits an Mädchengeburten. Bei einem Geburtendefizit von -11,45‰ kommt es langfristig zu einer Bevölkerungsschrumpfung und -alterung. Unter diesen Bedingungen wird die Gesamtbevölkerung im Jahr 2055 auf 25,09 Millionen zurück gehen.

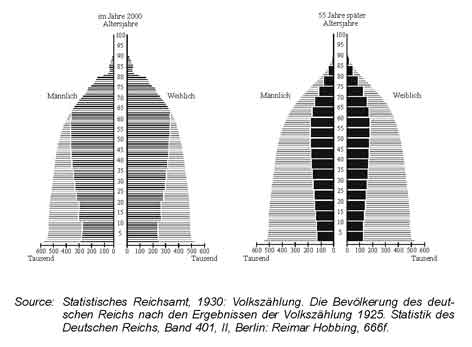

Die Geburten- und Sterbeziffern der stabilen Bevölkerung

Die Form der stabilen Altersstruktur, die sich nach Berechnungen der amtlichen Statistik bis 2055 herausgebildet hat, leitet über zu der Frage, wie sich unter diesen stabilen Verhältnissen die Geburten- und Sterbeziffern entwickeln werden. Die Dynamik des Alterungsprozesses der Bevölkerung, die zahlenmässige Zunahme in der Besetzung der höheren Altersgruppen, belegen die Kurvenverläufe der Sterbeziffern nach dem Entwicklungsfälle A und B (siehe Grafik 9.11).

Nach dem Entwicklungsfall A werden sich die Lebendgeborenen- und Gestorbenenzahl ständig die Waage halten. In diesem Fall wächst weder der Bevölkerungsbestand, noch verringert er sich, er bleibt vielmehr dauerhaft unverändert.

Nach dem Entwicklungsfall einer stabilen Bevölkerung bei gleichbleibender Geburtenhäufigkeit wie 1927, verringert sich der Geburtenüberschuss und mit Beginn der 1960er Jahre wird die weitere demografische Entwicklung durch einen Sterbefallüberschuss gekennzeichnet sein. Das Geburtendefizit beläuft sich auf ca. 1,3‰ und führt langfristig unter den Bedingungen einer stabilen Altersstruktur zu einem leichten Bevölkerungsrückgang.

Nach dem Entwicklungsfall B, die rückläufige Geburtenhäufigkeit um 25% bis 1955 und sich anschliessender Stabilität, setzt der Übergang vom Geburtenzum Sterbefallüberschuss bereits 1936 ein. Unter den Bedingungen einer sich herausbildenden stabilen Altersstruktur wird die weitere demografische Entwicklung durch ein Geburtendefizit von 11,4‰ bestimmt. Die Alterung der Bevölkerung wird unter den vorherrschenden Fruchtbarkeitsverhältnissen weiter voranschreiten.

Die endgültigen Geburten-, Sterbe- und Sterbefallüberschussziffern erschliessen sich aus der nachfolgenden Tabel

Tabel 9.12 – Die endgültigen Geburten-, Sterbe- und Sterbefallüberschussziffern

Bevölkerungspolitische Implikationen der amtlichen Vorausberechnungen- ein kurzer Exkurs

Neben dem Statistischen Reichsamt war es vor allem der Statistiker Friedrich Burgdörfer, der die Ergebnisse der demografischen Vorausschätzungen als eine außerordentliche ernste Warnung betrachtete. Diese Berechnungen hatten seines Erachtens den Nachweis erbracht, daß in der Zukunft sich das dynamische Volkswachstum nicht mehr fortsetzt und statt dessen die demografische Entwicklung massgeblich durch den dauerhaften Rückgang des Volksbestandes bestimmt wird (Burgdörfer, Lebensfrage, 1929).

Er wie auch andere Vertreter der Statistik und Nationalökonomie führten den Diskurs zu der Frage, wie den sich abzeichnenden demografischen Entwicklungstendenzen wirkungsvoll begegnet werden kann. Mit Sorge verfolgen sie die sich abzeichnende Differenzierung in der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeitsentwicklung zwischen der städtischen und ländlichen Bevölkerung als auch die wachsenden Differenzierungsprozesse der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit, die sich zwischen den verschiedenen sozialen Schichten und Berufsgruppen zeigten. All diese demografischen Faktoren verstärkten die Befürchtungen über nachhaltige Veränderungen des quantitativen wie auch qualitativen Bevölkerungsbestandes, der auf Basis der demografischen Vorausschätzungen und dem anhaltenden Rückgang der erwerbs- und reproduktionsfähigen Bevölkerung exemplifiziert wurde.

Die Befürchtungen vor einem dauerhaften Bevölkerungsrückgang beherrschen in den 1920er Jahren das demografische Denken nicht nur der Fachleute, sondern auch das der politischen Institutionen und Verbände. Sie entwerfen unzählige Konzepte, wie der anhaltende Geburten- und eheliche Fruchtbarkeitsrückgang aufgehalten werden könnte. Es wurde die abnehmende Bereitschaft der Frauen zur Geburt von mehreren Kindern beklagt. Statt der Geburt von vier und mehr Kindern, die für die Bewahrung des Bevölkerungsbestandes notwendig seien, würden die Frauen seit Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts nur mehr ein oder zwei Kinder zur Welt bringen. Nach Auszählungen von Burgdörfer waren zwischen 1901 und 1925 die Erstgeburten um ca. ein Viertel, die der Zweitgeburten um ca. 38%, die Geburten von dritten Kindern um ca. 57% und die von vierten und fünften Kindern um 75% bzw. 80% zurückgegangen. In diesen Tendenzen sah er eine wachsende Gefahr für den strukturellen und den zahlenmässigen Bevölkerungsbestand.

Angesichts dieser quantitativen und qualitativen Veränderungen des Bevölkerungsbestandes propagierten Friedrich Burgdörfer und viele seiner Kollegen eine pronatalistische Familien- und Bevölkerungspolitik, die auch eugenische Zielsetzungen verfolgen sollte. Bereits während des Ersten Weltkrieges wurde die Erstellung einer Familien- und Fruchtbarkeitsstatistik angeregt, die Bestandteil der Bevölkerungsstatistik sein sollte. Ziel dieses statistischen Erfassungs- und Auswertungssystems war es die “biologischen” Vorgänge, d. h. die Fruchtbarkeitsvorgänge einer jeden Familie zu überwachen und das Tempo und die Intensität der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit zu steuern (Beiträge, 1935, 6) Auf der Basis der familien- und fruchtbarkeitssatistischen Erhebungen regte Burgdörfer die Einführung der “Aufwuchsziffer” an. Diese sollte Auskunft darüber geben, wieviel der von 100.000 Frauen im Verlauf ihrer Fruchtbarkeitsperiode erbrachten Geburten das 15. Lebensjahr erreichen. Das 15. Lebensjahr markiert den Eintritt in das Erwerbsleben als auch in die reproduktive Fruchtbarkeitsperiode der weiblichen Bevölkerung und trage deshalb eine demografische Bedeutung.

Eine genaue Erfassung und Kontrolle des Heiratsalters und der Ehedauer mittels der Familien- und Fruchtbarkeitsstatistik ermögliche den “Gebärertrag” der verheirateten Frauen als auch die tatsächlich erbrachte Geburtenzahl und die Geburtenfolge zu ermitteln. Die Rückkehr zu dem Geburtenniveau, das von der weiblichen Bevölkerung um die Wende vom 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert erbracht wurde, entsprach auch der politischen Idee von der Wiederherstellung der “Volkskraft”, der “nationalen Erneuerung” und der “Rassetüchtigkeit”.

Dieser politische Leitgedanke bestimmte die familien- und bevölkerungspolitischen Zielstellungen zur quantitativen und qualitativen Erneuerung des “Volkskörpers”. Zur Wiederherstellung der demografischen Verhältnisse, wie sie vor dem Erstem Weltkrieg auf dem Territorium des Deutschen Reichs vorherrschten, wurde die Zusammenführung der quantitativen als auch qualitativen Familien- und Bevölkerungspolitik gefordert, die zwei Schwerpunkte verfolgte: Erstens sollte der Bevölkerungsbestand und das Bevölkerungswachstum gesichert und zweitens die Verschlechterung der Erbqualitäten aufgehalten und vor allem der Bevölkerungsbestand der gesunden und arbeitsfähigen Bevölkerungsgruppen erhöht werden (Denkschrift, 6). Im Artikel 119 der Weimarer Verfassung wurde die Verantwortung des Staats für die Gesundheit der Familie und des Nachwuchs verankert.

Die Einführung der familien- und fruchtbarkeitsstatistischen Erfassung war ursprünglich für die erste Volkszählung nach Ende des Ersten Weltkrieges vorgesehen. Hierzu kam es nicht, weil ebenso wie bei der nächst folgenden Volkszählung von 1925 die finanziellen Mittel für den Aufbau eines einheitlichen Systems der Familien- und Fruchbarkeitsstatistik fehlten. Erst Jahre später, unmittelbar nach der Konstituierung des nationalsozialistischen Staats wurden die erforderlichen finanziellen Ressourcen für den Aufbau der Familien- und Fruchtbarkeitsstatistik bereit gestellt und mit der Volkszählung vom 16 Juni 1933 auch erstmals für das gesamte Territorium des Deutschen Reichs praktiziert.

Um die in der Vorausberechnung berechneten und thematisierten Tendenzen, die zunehmende Bevölkerungsalterung und die rückläufige Geburtenund Fruchtbarkeitsentwicklung, gezielt beeinflussen und steuern zu können, wurden darüber hinaus auch die Gestaltungsmöglichkeiten in den Bereichen der Sozial- und Familienpolitik erörtert. Bereits zum Ende der Weimarer Republik wurden konkrete Massnahmen wie beispielsweise der Ausgleich der Familienlasten und die steuerliche Entlastung der Kinderreichen diskutiert. Erörtert wurden verschiedene Modelle, die Kinderlosen und Ledigen steuerlich stärker zu belasten als die Familien mit Kindern. Darüber hinaus sollte die Erziehungsbeihilfe, vor allem für Familien mit zwei Kindern eingeführt werden. Durch diese finanziellen Leistungen sollten sie zur Geburt eines dritten Kindes motiviert werden (Zahn, 1921, Elster, 1924, Harmsen, 1931, Burgdörfer, 1934).

Die breite Diskussion von Vorschlägen zur materiellen und ideellen Unterstützung der Familien und zur Absicherung der sozialen Lebenslagen der älter werdenden Bevölkerung, die hierüber nach 1930 geführt wurden, ist wenig untersucht worden und bleibt daher noch für längere Zeit der Forschungen vorbehalten.

Anmerkungen

1 Der Gesamtumfang der abgetretenen Gebiete belief sich auf ca. 13% der Gesamtfläche des Deutschen Reichs vom 1. Januar 1910. Ergänzend fügte das Statistische Reichsamt hinzu: “Rund 2 Millionen deutscher Männer im produktivsten Alter sind unmittelbar dem Krieg zum Opfer gefallen, rund 3 Millionen Kinder sind infolge des Krieges (bis Ende 1919) ungeboren geblieben und das Deutsche Reich wurde verpflichtet, rund 7 Millionen Einwohner an andere Staaten abzutreten. ” (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1925, Die abgetretenen Gebiete, 1925, 6).

2 In der Literatur werden für die Methoden zur Berechnung der künftigen Bevölkerungsentwicklung und -struktur unterschiedliche Begriffe wie Vorausberechnung, Vorausschätzung und Prognose verwendet. (Feichtinger, 1979; de Gans, 1999; Romanuic, 1991, 1994). Der Begriff der Bevölkerungsprognose wurde in beiden ersten Vorausberechnungen vermieden, obgleich die Berechnungszeiträume zwischen 50 bis 100 Jahren umfassen. In der zweiten Vorausberechnung werden einleitend auch “bedingte Voraussagen” über die künftige Bevölkerungsentwicklung und -struktur formuliert. (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, Ausblick, 663). In meiner

Abhandlung werde ich den Arbeitsbegriff “Vorausberechnung” verwenden.

3 Die zweite Vorausberechnung wurde völlig neu gerechnet und das Berechnungsmodell der stabilen Bevölkerung in Anwendung gebracht.

4 Friedrich Burgdörfer zählte zu den führenden Statistikern des Statistischen Reichsamtes. Seit 1921 gehörte er zunächst als Regierungsrat und später als Oberregierungsrat dem Statistischem Reichsamt an. Zu seinem Verantwortungsbereich zählte u.a. die Vorbereitung und Durchführung der Volkszählungen 1925, 1933 und 1939. Die wesentlichsten Ergebnisse seiner Vorausberechnungen veröffentlichte er 1932 in der Schrift “Volk ohne Jugend”. Mit ihr beförderte er die bevölkerungspolitischen Diskussionen in der Übergangsphase der auseinanderbrechenden Weimarer Republik und der sich konstituierenden NS-Herrschaft in Deutschland.

Ausführlich diskutiert Florence Vienne in ihrer Dissertation die Ergebnisse der Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung von Burgdörfer. (Vienne, 2000).

5. So stieg die in den Kriegsjahren die Sterblichkeit der 15 bis unter 20jährigen Männer um mehr als das dreifache, der 20 bis unter 25jährugen um mehr als fünfzehnfache, der 25 bis unter 30jährigen Männer um das zehnfache und das der 30 bis unter 35jährigen um mehr als das sechsfache.

6 In der Regel waren in den einzelnen Altersgruppen ca. 8 bis 10% weniger Frauen 1925 verheiratet als 1910.

7 Die Komponentenmethode wurde wenige Jahre zuvor in ihren Grundzügen von F.R. Sharpe & Alfred J. Lotka entwickelt. (Sharpe & Lotka, 1911).

8 In den Berechnungen für die Entwicklung der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit wurden die konstanten Zahlen der unehelichen Fruchtbarkeit integriert. Es wurde angenommen, dass diese Zahlen mittel- und langfristig sich nicht verändern werden.

9 Die Änderungsfaktoren ” beziehen sich jeweils auf das Basisjahr und beschreiben somit die zeitliche Entwicklung der beiden Komponenten in Relation zum Basisjahr. Die Änderungsfaktoren beziehen sich jeweils auf ganze Altersgruppen und Zeitabschnitte.” (Bretz, 2000, 653)

10 “Eine stationäre Bevölkerung ist eine fiktive Bevölkerung, die sich aus einer etwa 100 Jahre lang konstanten Geborenenzahl bei gleichzeitig gleichbleibenden Sterblichkeitsverhältnisse ergeben würde”. (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1926, Richtlinien, 42).

11 Allerdings zeigen sich auch deutliche Abweichungen in der Intensität des Bevölkerungswachstums nach den drei Entwicklungsfällen.

12 “Die Besserung der Sterblichkeitsverhältnisse, ausgedrückt durch das allmähliche Ansteigen der mittleren Lebenserwartung” lassen sich zur Bildung des Deutschen Reiches 1871 zurück verfolgen. (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 1926, Richtlinien,44).

13 Zu erwarten war mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit, dass die “im jugendlichen Alter stehende(n) Bevölkerung” sich beträchtlich verringern wird, während die Zahl “der im höheren und höchsten Alter stehenden Bevölkerung stark ansteigen wird.” (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1926, Richtlinien, 44).

14

15 Hierfür wurde die Familienstandsgliederung nach der Volkszählung vom 16. Juni 1925 und die Veränderungen der Heiratsverhältnisse in den Jahren 1925 bis 1927 zur Grundlage genommen. (Statistisches Reichsamt, Bewegung, 360, 6ff).

16 Damit wurden die Störungen im Bestand der männlichen Bevölkerung in den Altersgruppen mit der höchsten Heiratshäufigkeit ausgeschlosen.

17 Dieses Verfahren wählte die amtliche Statistik, weil sie weder über eine aktuelle Heiratstafel noch eine Familienstatitstik verfügte. Für die Berechnungen wurden Erhebungen von Preussen und des Freistaats Sachsen zur Entwicklung der Eheschliessungen und der geborenen Kinder in den Familien, gegliedert nach der

Ehedauer zugrunde gelegt. (Statistisches Reichsamt, Bewegung, 360, 22ff).

18 Allerdings ist “diese zyklische Wiederholung der ersten Geburtenwelle jedoch bei weitem nicht so stark ausgeprägt, wie gemeinhin erwartet werden dürfte” (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, Ausblick, 661).

19 Das bedeutet, dass die eheliche und uneheliche Fruchtbarkeit von 1955 ab, wie im zweiten Entwicklungsfall angenommen, unverändert bleibt, während die Lebendgeborenenzahl von Jahr zu Jahr beständig abnimmt.

20 Das Schwergewicht wird hierbei allerdings auf die Berechnung und Kommentierung der ersten zwei Entwicklungsfälle gelegt.

21 Der Entwicklungsfall B hat für die amtliche Statistik eine besondere Relevanz, weil “eine Abnahme der durchschnittlichen Geburtenhäufigkeit der gesamten Reichsbevölkerung um 25% des Standes von 1927 durchaus im Bereich des Möglichen liegt.” (Statistisches Reichsamt, 1930, Ausblick, 642).

22 In seinem Bevölkerungsmodell schliesst Lotka die Altersstruktur, die durch historische Zufälligkeiten entstanden war, aus.

23 Bei einem vollständigen Ersatz ist der rechnerische Ausdruck gleich 1. Bei nicht gesicherten Reproduktion ist der rechnerische Ausdruck kleiner als 1 und bei einer erweiterten Reproduktion ist der rechnerische Ausdruck grösser als 1.

Literaturverzeichnis

Brentano, Ludwig Josef (1909). Die Malthussche Lehre und die Bevölkerungsbewegung der letzten Dezennien. In: Abhandlungen der historischen Klasse des Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 24. Band, III. Abt., München.

Bretz, Manfred (2000). Methoden der Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung. In: Mueller, Ulrich, Nauck, Bernhard, Dieckmann, Andreas (Hrsg.), Handbuch der Demographie, pp. 643-681. Bd. 1. Berlin: Springer.

Burgdörfer,Friedrich (1929).Die Lebensfrage des deutschen Volks. Entgegnung auf Borgius’ “Grundsätzliche Bemerkungen” zu meinem Buche. Zeitschrift für Sexualwissenschaft, XVI.

Burgdörfer , Friedrich (1929). Der Geburtenrückgang und seine Bekämpfung. Die Lebensfrage des deutschen Volkes. Berlin.

Burgdörfer, Friedrich (1932). Volk ohne Jugend. Geburtenschwund und Überalterung des deutschen Volkskörpers. Ein Problem der Volkswirtschaft, der Sozialpolitik, der nationalen Zukunft. Berlin: Kurt Vowinckel.

Gans, Henk A. de (1999). Population Forecasting 1895-1945. The Transition to Modernity. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Denkschrift des Ministers des Innern über die Ergebnisse der Beratungen der Ministerialkommission für die Geburtenrückgangsfrage, Berlin 1917.

Elster, Ludwig (1924). Bevölkerungswesen: Bevölkerungslehre und Bevölkerungspolitik, 735-812. In: Handbuch der Staatswissenschaften. Jena: Fischer.

Feichtinger, Gustav (1979). Demographische Analyse und populationsdynamische Modelle. Grundzüge der Bevölkerungsmathematik. Wien: Springer.

Grotjahn, Alfred (1914). Geburten-Rückgang und Geburten-Regelung. Im Lichte der individuellen und sozialen Hygiene. (Zweite mit einem Nachwort versehene Ausgabe). Berlin: von Marcus.

Harmsen, Hans (1931). Praktische Bevölkerungspolitik. Ein Abriss ihrer Grundlagen, Ziele und Aufgaben. Berlin: Junker und Dünnhaupt.

Lotka, Alfred, J. (1925). On the true rate of natural increase of population. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 20, 305-39.

Mombert, Paul (1907). Studien zur Bevölkerungsbewegung in Deutschland in den letzten Jahrzehnten mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit. Karlsruhe: G. Braunsche Hofbuchdruckerei.

Müller, Johannes (1924). Der Geburtenrückgang. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Neue Beiträge zum deutschen Bevölkerungsproblem (1935). Sonderhefte zu Wirtschaft und Statistik, 15.

Romanuic, Anatole (1991). Bevölkerungsvorausschätzungen als Voraussage, Simulation und Zukunftsanalyse. Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaften, 17, 4, 394-410.

Romanuic, Anatole (1994). Reflection on population forecasting. From prediction to prosprective analysis. Canadian Studies in Population, 21, 2, 165-180.

Sharpe, Francis R. & Lotka, Alfred J. (1911). A problem in age-distribution. Philosophical Magazine, 6, 21, 435-428.

Statistisches Reichsamt (1922). Bewegung der Bevölkerung in den Jahren 1914 bis 1919. Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Band 276. Berlin: Reimar Hobbing.

Statistisches Reichsamt (1925). Die abgetretenen Gebiete und das Abstimmungsrecht und das Abstimmungsrecht an der Saar nach den Ergebnissen der Volkszählung vom 1.7.1910. Sonderhefte zur Wirtschaft und Statistik, Sonderheft 2. Berlin: Reimar Hobbing.

Statistisches Reichsamt (1926). Richtlinien zur Beurteilung des Bevölkerungsproblems Deutschlands für die nächsten 50 Jahre. In: Die Bewegung der Bevölkerung in den Jahren 1922 und 1923 und die Ursachen der Sterbefälle in den Jahren 1920 bis 1923. Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Band 316, 37-50.Berlin: Reimar Hobbing.

Statistisches Reichsamt (1929). Beiträge zum deutschen Bevölkerungsproblem. Der Geburtenrückgang im Deutschen Reich. Die allgemeine deutsche Sterbetafel für die Jahre 1924-1926. Sonderhefte zur Wirtschaft und Statistik, Sonderheft 5, 7-46. Berlin: Reimar Hobbing.

Statistisches Reichsamt (1930). Ausblick auf die zukünftige Bevölkerungsentwicklung im Deutschen Reich. In: Volkszählung. Die Bevölkerung des deutschen Reichs nach den Ergebnissen der Volkszählung 1925. Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Band 401, II, 641-683. Berlin: Reimar Hobbing.

Statistisches Reichsamt (1930). Die Bewegung der Bevölkerung in den Jahren 1925 bis 1927 mit vorläufigen Ergebnissen für die Jahre 1928 und 1929. Die Ursachen der Sterbefälle in den Jahren 1925 und 1926 und die Ergebnisse der Heilanstaltsstatistik in den Jahren 1925 und 1926. Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Band 360. Berlin: Reimar Hobbing.

Wolf, Julius (1912). Der Geburtenrückgang. Die Rationalisierung des Sexuallebens in unserer Zeit. Jena: Fischer.

Vienne, Florence (2000). “Volk ohne Jugend” de Friedrich Burgdörfer. Histoire d’un objet du savoir des années vingt à la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale Place of Publication: Paris Publisher: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESC). Remarks: Dissertation.

Zahn, Friedrich (1912). Deutsche Bevölkerungspolitik nach dem Kriege. In: Auschnetz, Gerhard, Berolzheimer, Fritz, u. a. (Hrsg), Handbuch der Politik – Die politische Erneuerung, pp. 307-317. Berlin: Rothschild.

—

About the Author:

Jochen Fleischhacker was, until 2002, the leader of the research unit “Projects on the History of Demographic Thinking” at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock (Germany) and a teacher of the history of demographic thinking and modelling at the Department of History of the University of Rostok. He has published on the the history of demographic methods and models and about the demogrpahic upheavals after 1990 in East Germany.

This essay was published earlier in: Populations, Projections and Politics. Critical and Historical Essays on Early Twentieth Centruy Population Forecasting. Edited by Jochen Fleischhacker, Henk A. de Gans and Thomas Burch. – Rozenberg Publishers 2003

Read also from the same book: Henk A. de Gans – The Innovation of Population Forecasting Methodology in the Inter-War Period: The Case of The Netherlands.

In 1654 wordt door de vergadering van de Heren XIX, het bestuur van de West-Indische Compagnie, verzucht dat het behouden van Curaçao een te grote last betekent voor de Compagnie. De banden met Nederland blijven. Eeuwen later, in 1998, verschijnt een bundel opstellen Breekbare banden en in 2001 luidt de titel van een departementaal gedenkboek Knellende Koninkrijksbanden. In De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk wordt verslag gedaan van de samenwerking tussen Nederland en de ‘warme delen’ van het Koninkrijk in de periode dat min of meer vanzelfsprekend werd overeengekomen dat de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba deel uit blijven maken van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden.

In 1654 wordt door de vergadering van de Heren XIX, het bestuur van de West-Indische Compagnie, verzucht dat het behouden van Curaçao een te grote last betekent voor de Compagnie. De banden met Nederland blijven. Eeuwen later, in 1998, verschijnt een bundel opstellen Breekbare banden en in 2001 luidt de titel van een departementaal gedenkboek Knellende Koninkrijksbanden. In De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk wordt verslag gedaan van de samenwerking tussen Nederland en de ‘warme delen’ van het Koninkrijk in de periode dat min of meer vanzelfsprekend werd overeengekomen dat de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba deel uit blijven maken van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden.