Monika Palmberger ~ How Generations Remember. Conflicting Histories And Shared Memories In Post-War Bosnia And Herzegovina

From: Introduction: Researching Memory and Generation

From: Introduction: Researching Memory and Generation

[…] The title of this book, How Generations Remember, is an allusion to the title of Paul Connerton’s seminal book, How Societies Remember (1989). In his book, Connerton opens up a timely discussion going beyond the textual and discursive understanding of remembering by concentrating on embodied/habitual memory and ritual aspects of memory. In terms of the study of generations he thus mainly discusses generations as transmitters or receivers of group memory. Although Connerton’s pioneering contribution to the study of memory is unquestioned, by focusing on how memory is passed down through the generations he primarily answers the question of how group memory is conveyed and sustained. This emphasis on transmission and persistence leaves open the question of where to locate the individual, the agent, the force and possibility for reflexivity and change (Argenti and Schramm 2010; Shaw 2010). My study, in concentrating on the role of generational positioning, reveals that past experiences inform present stances, but also shows that it is the actor in the present that gives meaning to the past. This is also true for narratives of the past that are passed on from older to younger generations, and are then scrutinised and contextualised by the latter. It is suggested that people’s sense of continuity can deal with the inconsistencies that arise with this transfer between generations. It is this field of tension between collective and personal, and between persistence and change that is central in the discussion of generational positioning in this book.

Dowload book: http://link.springer.com/book/

The Purchase Of The Farm Braklaagte By The Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa – Whose Land Is It Anyway? (1908-1935)

Braklaagte, registered as farm number 168 on the Transvaal farm register (the number was changed in the second half of the twentieth century to JP-90), was 3,152 morgen and 529 square rood in size, which is equal to 2,700.5441 ha in metric measurements.

The first title deed to the farm was registered in October 1874 in the name of Diederik Jacobus Coetzee. Ownership of the farm was transferred several times to other white farmers. W.M. Beverley was the last white owner before the farm was bought by the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa.

In 1906 a dispute arose in the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa tribe of Dinokana in Moiloa’s Reserve between Abraham Pogiso Moiloa and Israel Keobusitse Moiloa. When Abraham’s father, Ikalafeng, had died in 1893 he was a minor and Israel, Ikalafeng’s younger brother, would for a number of years act as regent. When Israel had to hand over the bokgosi (chieftainship) to Abraham in 1906 differences arose between them. A section of the tribe, led by Israel, moved eastward and settled at Leeuwfontein.

Already in 1876 Leeuwfontein had been bought for the tribe by chief Sebogodi Moiloa of Dinokana at the price of 200 head of large cattle, equivalent to about £1,000, but the transfer of the farm to the tribe had not yet been effected. ‘Quite an exodus’ of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa took place from Dinokana to Leeuwfontein and by 1907 the majority of Israel’s adherents had settled there.

Read more

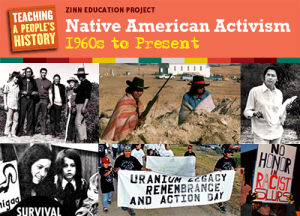

Native American Activism: 1960s To Today

The month of November is often the only time students learn about Native Americans, and usually in the past tense or as helpless “wards of the state.” To counter this, we offer this collection of recent Native movements and activists who have continued to struggle for sovereignty, dignity, and justice for their communities. The financial and colonial drive that usurps Native peoples ways of life is not just relegated to the past; it continues today. Here are just a few stories of struggle and achievement since the late 1960s.

The month of November is often the only time students learn about Native Americans, and usually in the past tense or as helpless “wards of the state.” To counter this, we offer this collection of recent Native movements and activists who have continued to struggle for sovereignty, dignity, and justice for their communities. The financial and colonial drive that usurps Native peoples ways of life is not just relegated to the past; it continues today. Here are just a few stories of struggle and achievement since the late 1960s.

For Native American Heritage Month (and beyond), view lessons and resources at the Zinn Education Project.

Read more: http://zinnedproject.org/native-american-activism-1960s-to-today/

God wil het! Reizen in het spoor van de kruisvaarders

De historische importantie van de Kruistochten die tussen de 11e en de 15e eeuw plaats vonden in Europa en het Midden-Oosten wordt in het huidige tijdperk doorgaans door Westerse historici en politici onderschat.

Lejo Siepe en Robert Mulder volgden enkele jaren geleden het spoor van de eerste Kruistocht en ontdekten dat met name in de Arabische wereld de herinneringen aan de Kruistochten nog altijd levendig zijn. In de hoofden van veel moslims is deze historische gebeurtenis actueler dan ooit. De islamitische wereld voelt zich bedreigd door het Westen. Het Westen voelt zich bedreigd door de islamitische wereld. Een geschiedenis herhaalt zich. Heden ten dage worden in zowel de christelijke stromingen als in de islam de geloofsstellingen weer betrokken, gebaseerd op oude mythen, sagen en legendes. Hebben de Kruistochten in dit verband meer dan een symbolische betekenis?

In dit reisverslag langs de route van de eerste Kruistocht hebben Lejo Siepe en Robert Mulder geprobeerd antwoord te vinden op de vraag of er sprake is van een nieuw vijandsbeeld gebaseerd op oude vooroordelen. De auteurs spraken in Europa en in het Midden Oosten met vooraanstaande historici, schrijvers, filosofen en geestelijken (onder andere Amos Oz, Amin Maalouf, Sadik Al Azm, Benjamin Kedar, Halil Berktay) over de actuele invloed van de Kruistochten op onze moderne geschiedenis en de onverminderd voortdurende godsdienstige conflicten tussen moslims, joden en christenen.

Inhoudsopgave

Hoofdstuk Een – Reizen in het spoor der kruisvaarders – Inleiding

Hoofdstuk Twee – Duitsland: de vijanden van God

Hoofdstuk Drie – Hongarije: de koning der boeken

Hoofdstuk Vier – De Balkan: een eeuwig strijdtoneel

Hoofdstuk Vijf – Bulgarije

Hoofdstuk Zes – Constantinopel: in het kamp van de vijand

Hoofdstuk Zeven – Nicaea en Dorylaeum: Sterf dan honden!

Hoofdstuk Acht – Cappadocië: De vlakte des doods

Hoofdstuk Negen – Antiochië: het verraad van het harnasmasker

Hoofdstuk Tien – Antiochië: een teken van God

Hoofdstuk Elf – Syrie: twee grote leiders voor een geweldig volk

Hoofdstuk Twaalf – Libanon: het land van ruines

Hoofdstuk Dertien – Israel: het land van belofte

Hoofdstuk Veertien – Jeruzalem: God wil het!

Fountain Hughes ~ Voices From The Days Of Slavery

Fountain Hughes (age 101 at the time of this interview) recalls his younger years when he and his family lived as slaves as well as some good advice on how to spend money.

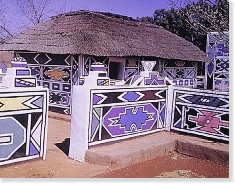

The Ndebele Nation

12-05-2015 ~ With an Introduction by Milton Keynes

The Ndebele of Zimbabwe, who today constitute about twenty percent of the population of the country, have a very rich and heroic history. It is partly this rich history that constitutes a resource that reinforces their memories and sense of a particularistic identity and distinctive nation within a predominantly Shona speaking country. It is also partly later developments ranging from the colonial violence of 1893-4 and 1896-7 (Imfazo 1 and Imfazo 2); Ndebele evictions from their land under the direction of the Rhodesian colonial settler state; recurring droughts in Matabeleland; ethnic forms taken by Zimbabwean nationalism; urban events happening around the city of Bulawayo; the state-orchestrated and ethnicised violence of the 1980s targeting the Ndebele community, which became known as Gukurahundi; and other factors like perceptions and realities of frustrated economic development in Matabeleland together with ever-present threats of repetition of Gukurahundi-style violence—that have contributed to the shaping and re-shaping of Ndebele identity within Zimbabwe.

The Ndebele history is traced from the Ndwandwe of Zwide and the Zulu of Shaka. The story of how the Ndebele ended up in Zimbabwe is explained in terms of the impact of the Mfecane—a nineteenth century revolution marked by the collapse of the earlier political formations of Mthethwa, Ndwandwe, and Ngwane kingdoms replaced by new ones of the Zulu under Shaka, the Sotho under Moshweshwe, and others built out of Mfecane refugees and asylum seekers. The revolution was also characterized by violence and migration that saw some Nguni and Sotho communities burst asunder and fragmenting into fleeing groups such as the Ndebele under Mzilikazi Khumalo, the Kololo under Sebetwane, the Shangaans under Soshangane, the Ngoni under Zwangendaba, and the Swazi under Queen Nyamazana. Out of these migrations emerged new political formations like the Ndebele state, that eventually inscribed itself by a combination of coercion and persuasion in the southwestern part of the Zimbabwean plateau in 1839-1840. The migration and eventual settlement of the Ndebele in Zimbabwe is also part of the historical drama that became intertwined with another dramatic event of the migration of the Boers from Cape Colony into the interior in what is generally referred to as the Great Trek, that began in 1835. It was military clashes with the Boers that forced Mzilikazi and his followers to migrate across the Limpopo River into Zimbabwe.

As a result of the Ndebele community’s dramatic history of nation construction, their association with such groups as the Zulu of South Africa renowned for their military prowess, their heroic migration across the Limpopo, their foundation of a nation out of Nguni, Sotho, Tswana, Kalanga, Rozvi and ‘Shona’ groups, and their practice of raiding that they attracted enormous interest from early white travellers, missionaries and early anthropologists. This interest in the life and history of the Ndebele produced different representations, ranging from the Ndebele as an indomitable ‘martial tribe’ ranking alongside the Zulu, Maasai and Kikuyu, who also attracted the attention of early white literary observers, as ‘warriors’ and militaristic groups. This resulted in a combination of exoticisation and demonization that culminated in the Ndebele earning many labels such as ‘bloodthirsty destroyers’ and ‘noble savages’ within Western colonial images of Africa.

Ndebele History

Ndebele History

With the passage of time, the Ndebele themselves played up to some of the earlier characterizations as they sought to build a particular identity within an environment in which they were surrounded by numerically superior ‘Shona’ communities. The warrior identity suited Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. Their Shona neighbours also contributed to the image of the Ndebele as the militaristic and aggressive ‘other’. Within this discourse, the Shona portrayed themselves as victims of Ndebele raiders who constantly went away with their livestock and women—disrupting their otherwise orderly and peaceful lives. A mythology thus permeates the whole spectrum of Ndebele history, fed by distortions and exaggerations of Ndebele military prowess, the nature of Ndebele governance institutions, and the general way of life.

My interest is primarily in unpacking and exploding the mythology within Ndebele historiography while at the same time making new sense of Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. My intention is to inform the broader debate on pre-colonial African systems of governance, the conduct of politics, social control, and conceptions of human security. Therefore, the book The Ndebele Nation (see: below) delves deeper into questions of how Ndebele power was constructed, how it was institutionalized and broadcast across people of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. These issues are examined across the pre-colonial times up to the mid-twentieth century, a time when power resided with the early Rhodesian colonial state. I touch lightly on the question of whether the violent transition from an Ndebele hegemony to a Rhodesia settler colonial hegemony was in reality a transition from one flawed and coercive regime to another. Broadly speaking this book is an intellectual enterprise in understanding political and social dynamics that made pre-colonial Ndebele states tick; in particular, how power and authority were broadcast and exercised, including the nature of state-society relations.

What emerges from the book is that while the pre-colonial Ndebele state began as an imposition on society of Khumalo and Zansi hegemony, the state simultaneously pursued peaceful and ideological ways of winning the consent of the governed. This became the impetus for the constant and ongoing drive for ‘democratization,’ so as contain and displace the destructive centripetal forces of rebellion and subversion. Within the Ndebele state, power was constructed around a small Khumalo clan ruling in alliance with some dominant Nguni (Zansi) houses over a heterogeneous nation on the Zimbabwean plateau. The key question is how this small Khumalo group in alliance with the Zansi managed to extend their power across a majority of people of non-Nguni stock. Earlier historians over-emphasized military coercion as though violence was ever enough as a pillar of nation-building. In this book I delve deeper into a historical interrogation of key dynamics of state formation and nation-building, hegemony construction and inscription, the style of governance, the creation of human rights spaces and openings, and human security provision, in search of those attributes that made the Ndebele state tick and made it survive until it was destroyed by the violent forces of Rhodesian settler colonialism.

The book takes a broad revisionist approach involving systematic revisiting of earlier scholarly works on the Ndebele experiences in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and critiquing them. A critical eye is cast on interpretation and making sense of key Ndebele political and social concepts and ideas that do not clearly emerge in existing literature. Throughout the book, the Ndebele historical experiences are consistently discussed in relation to a broad range of historiography and critical social theories of hegemony and human rights, and post-colonial discourses are used as tools of analysis.

Empirically and thematically, the book focuses on the complex historical processes involving the destruction of the autonomy of the decentralized Khumalo clans, their dispersal from their coastal homes in Nguniland, and the construction of Khumalo hegemony that happened in tandem with the formation of the Ndebele state in the midst of the Mfecane revolution. It further delves deeper into the examination of the expansion and maturing of the Ndebele State into a heterogeneous settled nation north of the Limpopo River. The colonial encounter with the Ndebele state dating back to the 1860s culminating in the imperialist violence of the 1890s and the subsequent colonization of the Ndebele in 1897 is also subjected to consistent analysis in this book.

What is evident is that the broad spectrum of Ndebele history was shot through with complex ambiguities and contradictions that have so far not been subjected to serious scholarly analysis. These ambiguities include tendencies and practices of domination versus resistance as the Ndebele rebelled against both pre-colonial African despots like Zwide and Shaka as well as against Rhodesian settler colonial conquest. The Ndebele fought to achieve domination, material security, political autonomy, cultural and political independence, social justice, human dignity, and tolerant governance even within their state in the face of a hegemonic Ndebele ruling elite that sought to maintain its political dominance and material privileges through a delicate combination of patronage, accountability, exploitation, and limited coercion.

The overarching analytical perspective is centred on the problem of the relation between coercion and consent during different phases of Ndebele history up to their encounter with colonialism. Major shifts from clan to state, migration to settlement, and single ethnic group to multi-ethnic society are systematically analyzed with the intention of revealing the concealed contradictions, conflict, tension, and social cleavages that permitted conquest, desertions, raiding, assimilation, domination, and exploitation, as well as social security, communalism, and tolerance. These ideologies, practices and values combined and co-existed uneasily, periodically and tendentiously within the Ndebele society. They were articulated in varied and changing idioms, languages and cultural traditions, and underpinned by complex institutions. Read more