Dat Dylan Farrow, de adoptiefdochter van Mia Farrow, haar beschuldiging van seksueel misbruik door Mia’s partner Woody Allen weer in de publiciteit bracht, had ten minste twee gevolgen. Er meldde zich een tweede aanklaagster: Christina Engelhardt, inmiddels 60, zou vanaf 1976, toen een 16-jarig fotomodel, een verhouding gehad hebben met de toen 41-jarige regisseur, een relatie die acht jaar duurde. En het haalde weer de verhouding en vervolgens het huwelijk in veel media naar boven van Allen met een van Farrows andere adoptiedochters, de 36 jaar jongere Soon-Yi.

Dat Dylan Farrow, de adoptiefdochter van Mia Farrow, haar beschuldiging van seksueel misbruik door Mia’s partner Woody Allen weer in de publiciteit bracht, had ten minste twee gevolgen. Er meldde zich een tweede aanklaagster: Christina Engelhardt, inmiddels 60, zou vanaf 1976, toen een 16-jarig fotomodel, een verhouding gehad hebben met de toen 41-jarige regisseur, een relatie die acht jaar duurde. En het haalde weer de verhouding en vervolgens het huwelijk in veel media naar boven van Allen met een van Farrows andere adoptiedochters, de 36 jaar jongere Soon-Yi.

Dat roept onder veel meer de vraag op naar het beeld en de rol van vrouwen in Allens films. Lopen feit en fictie daarin door elkaar? Ziet de regisseur Allen de feiten uit het leven van de burger Allen wel voldoende onder ogen? Kortom, tijd om leven en werk van een van de belangrijkste nog actieve regisseurs ter wereld in een context te plaatsen. Ofwel: Woody Allen voor beginners.

Tijdlijn

De 50 films die Woody Allen in de afgelopen 50 jaar geschreven en geregisseerd heeft, zijn grofweg in te delen in vier periodes. Niet meegeteld worden de films waaraan hij in een andere hoedanigheid heeft meegewerkt, bijvoorbeeld zijn bewerking van het Japanse Kaki no Kagi naar What’s up, Tiger Lily? (1966) zonder dat hij een woord Japans kende, de James Bond-persiflage Casino Royale (1967) of de tekenfilm Antz (1998) waaraan hij zijn stem leende. Of films waarin hij wel meespeelt maar die hij niet geregisseerd heeft, zoals The Front (1976) over de politieke heksenjacht in het Amerika van de jaren 50, Scenes from a mall (1991) tegenover Bette Midler en – misschien zijn beste rol – Fading gigolo (2013) van en met John Turturro.

Uitzondering is Play it again, Sam (1972), geregisseerd door Herbert Ross maar essentieel deel van de Allen-canon. Het is oorspronkelijk een toneelstuk, geschreven door Allen. Na de Broadway-première in februari 1969 werd het 453 maal uitgevoerd, bijna alle malen met Allen zelf in de hoofdrol. Tegenspeelster was de jonge talentvolle actrice Diane Keaton, die vervolgens tussen 1972 en 1979 in zes films zijn leading lady zou zijn, en trouwens ook privé een hoofdrol speelde. Toen het plan opgevat werd voor een verfilming van het stuk, was Allens affiniteit ermee al grotendeels voorbij, reden om daarvoor Ross in te huren.

Play it again, Sam is de eerste film waarin hij, gesouffleerd door Humphrey Bogart in diens Casablanca-rol, zijn moeite met relaties onder woorden brengt en hoort daarom in de lijst van 50. (Voor de volledigheid: de titel van Allens film komt in die bewoording niet voor in Casablanca (1942). Ingrid Bergman vraagt Sam, de barpianist van Rick’s Place, nog één keer As time goes by te spelen met de woorden ”Play it once, Sam. For old times’ sake”, gevolgd door “Play it, Sam. Play “As Time Goes By”).

De eerste periode in Allens oeuvre begint met Take the money and run (1969) en Bananas (1971), films die het best gekarakteriseerd kunnen worden als cinematografische vingeroefeningen: het zijn aan elkaar geplakte sketches, het filmverhaal stelt weinig voor en de humor is voornamelijk visueel.

Hoewel een toenemende vaardigheid op een groeiend vakmanschap wees, bijvoorbeeld in het uit zeven sketches bestaande Everything you always wanted to know about sex* (*but were afraid to ask) (1972) en Love and death (1975), zou het nog tot 1977 duren voor hij met Annie Hall een groot publiek bereikte.

Annie Hall was niet alleen de doorbraak voor Woody Allen als serieus genomen scenarist en regisseur, waarvoor het ultieme bewijs geleverd werd toen zijn vakgenoten de film vier Academy Awards waard vonden: de Oscars voor beste film, beste oorspronkelijke scenario, beste regie en beste vrouwelijke hoofdrol. Die laatste betekende namelijk ook voor Diane Keaton, die de titelrol speelde, erkenning als actrice en een reputatie als stijlicoon op grond van de door haar zelf ontworpen garderobe van Annie Hall.

Voor veel Woodynites is echter het eerste echte hoogtepunt Manhattan (1979). Annie Hall beproeft een overdaad aan technieken: split screen, gelijktijdig getoonde sessies van beide hoofdpersonen bij de psychiater, flashbacks, een monoloog door een jonge versie van Woody, en kartonnen versie van de media-filosoof Marshall McLuhan die tot leven komt en zich in een discussie mengt. De hele la met kunstgrepen wordt opengetrokken. En de lijst had nog langer kunnen zijn: in een subplot vermoeden Allen en Keaton een moord in hun appartementencomplex en gaan ze op onderzoek uit, met alle gevaren van dien. Dat subplot heeft Allen op de plank laten liggen en pas in 1992 uitgewerkt tot Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993), met daarin onder andere een fraaie hommage aan de spiegelscène in Orson Welles’ The Lady from Shanghai (1947).

Oorspronkelijk zou Annie Hall Anhedonia heten, wat Allen pas twee weken voor de film uitgebracht werd veranderde in de huidige titel. Anhedonisme is het niet kunnen beleven van plezier, een veel voorkomend symptoom bij depressie. Kees van Kooten schreef in 1984 Hedonia. Een opstel, waarin de schrijver filosofeert over onderwerpen als de humor van Woody Allen en diens “natuurleuk”, terwijl zijn vrouw Barbara in New York is voor een vraaggesprek met Allen.

Daarentegen zoekt Manhattan het in eenvoud: de in scherp zwart-wit gefilmde skyline van Manhattan, ondersteund door de openingsmaten van George Gershwins Rhapsody in blue, vormt wellicht de mooiste filmische ode aan New York.

Twee scènes zijn bepalend voor de contrapunten in veel van Allens werk: de neurotische man, die lust en bindingsangst maar niet met elkaar in balans kan brengen, en de meestal aantrekkelijke jonge vrouw die tot veel bereid is om een relatie in stand te houden. Manhattan begint als Isaac tot vijfmaal toe een openingszin voor zijn roman formuleert, een roman die tijdens het verloop van de film, maar waarschijnlijk ook daarna, niet veel verder komt dan dat begin. Daar tegenover staat een scène tegen het slot, waarin hij zijn veel jongere beeldschone vriendin voor de zoveelste keer op het verkeerde been zet. Wie kan met droge ogen aanzien hoe de toen 17-jarige Mariel Hemingway met trillende onderlip fluistert: “Gee, now I don’t feel so good”?

De tweede fase, het serieuze werk, begint met Annie Hall en leidt via onder meer Manhattan, Hannah and her sisters (1986) en Alice (1990), naar 1992, het jaar waarin het vrijwel voltooide Shadows and fog (1991) voorrang moest verlenen aan Husbands and wives (1992) om publicitair zo veel mogelijk gebruik te kunnen maken van alle onappetijtelijke rumoer tussen Allen en Mia Farrow. In 1992 kwam zijn relatie aan het licht met Soon-Yi. Dat in Husbands and wives een stel op nogal rationele gronden uit elkaar gaat en de man voor een aanzienlijk jongere vriendin kiest, heeft de omzet zeker geen kwaad gedaan.

De tweede fase, het serieuze werk, begint met Annie Hall en leidt via onder meer Manhattan, Hannah and her sisters (1986) en Alice (1990), naar 1992, het jaar waarin het vrijwel voltooide Shadows and fog (1991) voorrang moest verlenen aan Husbands and wives (1992) om publicitair zo veel mogelijk gebruik te kunnen maken van alle onappetijtelijke rumoer tussen Allen en Mia Farrow. In 1992 kwam zijn relatie aan het licht met Soon-Yi. Dat in Husbands and wives een stel op nogal rationele gronden uit elkaar gaat en de man voor een aanzienlijk jongere vriendin kiest, heeft de omzet zeker geen kwaad gedaan.

In deze fase verschenen enkele van zijn beste werken, zoals Zelig (1983), Radio Days (1987) en het hoogtepunt in zijn oeuvre, Crimes and misdemeanors (1989). De rest van de jaren 90, de derde periode, biedt weinig nieuws, laat staan interessants, al zijn Bullets over Broadway (1994), Mighty Aphrodite (1995), Celebrity (1998) en Sweet and lowdown (1999) om uiteenlopende redenen zeker genietbaar.

De laatste periode, vanaf Manhattan Murder Mystery tot heden – Café Society (2016) en Wonder Wheel (2017) -, kent vooral routineus gemaakte, bijna verwaarloosbare films – Hollywood Ending (2002), Anything else (2003), Scoop (2006), Whatever works (2009), You will meet a tall dark stranger (2010), To Rome with love (2012) -, om de paar jaar afgewisseld met een meesterwerkje als Midnight in Paris (2011) en Blue Jasmine (2013).

Opbrengst

Allen heeft verscheidene reputaties; een daarvan wil, dat zijn films niet heel rendabel zijn. En inderdaad, September, Cassandra’s dream en Another woman zijn met een opbrengst van respectievelijk nog geen half miljoen dollar, krap een miljoen dollar en amper anderhalf miljoen dollar niet of nauwelijks uit de kosten gekomen. Maar het blijkt ontzettend mee te vallen. Volgens de website Box Office Mojo heeft zijn werk tot nu toe zo’n $ 591 miljoen dollar opgeleverd. Het beste deed Midnight in Paris het, met $ 57 miljoen, gevolgd door Hannah and her sisters en Manhattan, beide goed voor zo’n $ 40 miljoen.

Aangepast voor de inflatie, dat wil zeggen omgerekend naar wat een bioscoopkaartje nu zou kosten, ontstaat er een ander beeld. Dan blijkt er het meest verdiend te zijn aan Annie Hall (een kleine $ 155 miljoen). En na Manhattan ($ 143 miljoen) en ‘Hannah’ ($ 97 miljoen) scoren enkele van zijn oudste films opmerkelijk goed: op de vierde, vijfde en zesde plaats op de ranglijst staan ‘Everything you always wanted to know’ ($ 95 miljoen), Sleeper ($ 93 miljoen) en Love and death ($ 88 miljoen). Voor inflatie gecorrigeerd heeft het hele oeuvre al ruim $ 1,4 miljard opgebracht.

In die gevallen dat een film geen winst opleverde, kan dat niet gelegen hebben aan de exorbitante honoraria. Allen betaalt al zijn acteurs en actrices, ongeacht hun reputatie, hetzelfde honorarium, namelijk het minimum door de vakbonden bedongen dagloon. Daarom compenseren velen van hen die beloning met de eer gevraagd te zijn voor een Woody Allen-film. Die eer was voldoende voor een scala aan topacteurs, van de Amerikanen John Malkovich, Leonardo DiCaprio, Danny DeVito en William Hurt tot de Spanjaarden Javier Bardem en Antonio Banderas en de Britten Michael Caine, Hugh Grant, Colin Firth en Anthony Hopkins.

De lijst met actrices is nog indrukwekkender: Meryl Streep, Charlotte Rampling, Madonna, Julia Roberts, Charlize Theron, Cate Blanchett en Kate Winslet zijn daar slechts een greep uit.

Het selecteren van vrouwen biedt een door hormonen gedreven scenarist of regisseur een extra voordeel: hij kan zo veel zoen- of seksscènes inlassen als hij voor het verhaal noodzakelijk acht. Niet voor niets castte Allen Scarlett Johansson in drie achtereenvolgende films (Match Point, Scoop en Vicky Christina Barcelona) en niet voor niets zal hij scènes bedacht hebben waarin hij de oudere maar nog immer viriele man speelt, bij voorkeur een universitair docent of schrijver of journalist, maar in elk geval iemand die zijn intellectueel overwicht aanwendt in contacten met jonge vrouwen. Dat gebeurt bijvoorbeeld tegenover Juliette Lewis in Husbands and wives, Mira Sorvino in Mighty Aphrodite en vooral Debra Messing in Hollywood Ending, maar het meest onomwonden tegenover Mariel Hemingway in Manhattan.

Het selecteren van vrouwen biedt een door hormonen gedreven scenarist of regisseur een extra voordeel: hij kan zo veel zoen- of seksscènes inlassen als hij voor het verhaal noodzakelijk acht. Niet voor niets castte Allen Scarlett Johansson in drie achtereenvolgende films (Match Point, Scoop en Vicky Christina Barcelona) en niet voor niets zal hij scènes bedacht hebben waarin hij de oudere maar nog immer viriele man speelt, bij voorkeur een universitair docent of schrijver of journalist, maar in elk geval iemand die zijn intellectueel overwicht aanwendt in contacten met jonge vrouwen. Dat gebeurt bijvoorbeeld tegenover Juliette Lewis in Husbands and wives, Mira Sorvino in Mighty Aphrodite en vooral Debra Messing in Hollywood Ending, maar het meest onomwonden tegenover Mariel Hemingway in Manhattan.

In haar autobiografie Out came the sun (2015) beschrijft zij hoe de gevierde filmmaker, zelf 44 jaar oud, de eerste was met wie zij, toen 17, kuste: “I had never kissed anybody. So the kiss in the cab around Central Park terrified me. I was worried about it for weeks (…). Fortunately it was a long shot and I didn’t have to do much . . . he attacked me like I was a linebacker.” Een verdediger in American Football dus.

Sexy Woody

Een veel gestelde vraag is die naar de mate waarin de privépersoon Woody Allen samenvalt met het filmpersonage, dat getypeerd kan worden als een joodse, neurotische, hypochondrische, druk pratende, heftig gesticulerende inwoner van een grote stad – Annie Hall werd in Duitsland uitgebracht als Der Stadtneurotiker -, veelal maar niet uitsluitend op het gebied van relaties een besluiteloze brekebeen: als hij een vriendin heeft, wordt hij verliefd op een ander, niet zelden de partner van zijn beste vriend, en als hij die veroverd heeft, wil hij op zijn knieën terug naar de vorige.

Het ligt voor de hand dat een zo omvangrijk en persoonlijk oeuvre voor een belangrijk deel autobiografisch geïnspireerd is. Zelf heeft hij zich daar meermalen in ondubbelzinnige bewoordingen over uitgelaten. In een interview zegt hij “I’ve been telling people for my entire life in the movies that there’s not a huge similarity between me on screen and me in real life, but for some reason they don’t want to know that. And I think it even detracts from their

enjoyment of the movie”. (Zo lang ik in de filmwereld werk, heb ik steeds gezegd dat er geen enorme gelijkenis bestaat tussen mijzelf op het scherm en mij in het echte leven, maar om de een of andere reden wil men dat niet weten. En ik geloof zelfs dat het ten koste gaat van het plezier van het zien van de film.)

Het zou een misvatting zijn in het Woody-personage – ook als het niet door Allen zelf gespeeld wordt, maar bijvoorbeeld door de Britse acteur Kenneth Branagh, die in Celebrity een perfecte imitatie geeft – in alle gestamel en zenuwtrekjes een natuurgetrouwe kopie van de privépersoon Allen te zien. Maar het is evenmin te ontkennen, dat in het personage Woody Allen veel meer van de mens Allen te herkennen valt dan bij andere regisseurs die in hun eigen films spelen, zoals bij Charles Chaplin of Orson Welles.

Wellicht heeft Allen ooit, bewust of onbewust, gedacht: als jullie menen dat ik in mijn filmrollen mijzelf speel, dan moet het omgekeerde ook waar zijn. Dus als ik steeds een onweerstaanbaar aantrekkelijke en zeer goede minnaar speel, dan zullen jullie ook moeten geloven dat ik dat in het echt ook ben.

Want seks is nooit ver weg in een film van Woody Allen. Talrijk zijn de scènes waarin hij voldaan achterover leunt na weer een proeve van zijn mannelijk kunnen. En nooit is er een seksscène waarin hij beteuterd toegeeft dat het er deze keer helaas niet in zat. Opmerkelijk, bijna obsessief veel belangstelling toont hij voor orale seks, een interesse die al verwoord werd tijdens zijn stand up-comedy monologen. Er bestaat een opname uit 1965, waarin hij vertelt hoe Zweden en Denemarken op seksueel gebied heel vrij zijn, maar dat er een taboe rust op eten. Food is a dirty subject. En hij geeft als voorbeeld: “There are some women that will eat a bagel, but they won’t put creamcheese on it. And if you ask them why, they’ll say ‘Well, I don’t do that’.” Het ovationele gelach bewijst dat het publiek exact weet waar hij het over heeft en “I don’t do that” moet veel Amerikaanse mannen bekend in de oren hebben geklonken.

Maar ook in films komt zijn voorkeur ruim aan bod, in twee daarvan in het bijzonder. In Deconstructing Harry (1997) gaat Julia Louis-Dreyfus, bekend als de onkreukbare Elaine uit de serie Seinfeld, op haar knieën voor Richard Benjamin, die ondertussen door het keukenraam het gezelschap in de gaten houdt dat op het gazon staat te borrelen, een situatie die gecompliceerd wordt als de blinde grootmoeder van ”Julia” de keuken betreedt en nietsvermoedend een gesprek begint (maar dan is het hitsige stel al een fase verder).

Maar ook in films komt zijn voorkeur ruim aan bod, in twee daarvan in het bijzonder. In Deconstructing Harry (1997) gaat Julia Louis-Dreyfus, bekend als de onkreukbare Elaine uit de serie Seinfeld, op haar knieën voor Richard Benjamin, die ondertussen door het keukenraam het gezelschap in de gaten houdt dat op het gazon staat te borrelen, een situatie die gecompliceerd wordt als de blinde grootmoeder van ”Julia” de keuken betreedt en nietsvermoedend een gesprek begint (maar dan is het hitsige stel al een fase verder).

De Harry uit de titel (de ‘Woody’ in deze film) heeft een zuster, Helen, die zo orthodox joods is, dat ze voor alles bidt. Niet alleen voor het nuttigen van een glas wijn, ook in bed mompelt ze, op het geëigende moment, “Boreh p’ree ha(gofen) blowjob”, een regel uit een Hebreeuws gebed, letterlijk: Schepper van de vrucht van de wijnstok.

Zelf laat Harry Cookie komen, een callgirl die hem voor $ 200,- moet vastbinden, slaan en oraal bevredigen. In die volgorde. Na een blijkbaar happy ending complimenteert hij haar met “They should put your lips in the Smithsonian” (een gigantisch museum in Washington). Omdat ze het zielig vindt dat hij zo depressief is, mag hij van Cookie nog een keer. Voor niets.

In Celebrity komt Kenneth Branagh alleen in een kamer terecht met Melanie Griffith, die weliswaar getrouwd is maar een fysiek essentieel onderscheid hanteert: “I can’t have sex with you! My body belongs to my husband and there is no way that I could betray him in that way. But what I do from the neck up is a different story”.

Hilarisch is de scène waarin de neurotische Robin (Judy Davis) seksles neemt bij een prostituee, gespeeld door Bebe Neuwirth, bekend en geliefd als Lilith, de vrouwelijke psychiater in de sitcoms Cheers en Frasier. Die geeft aanschouwelijk onderricht met een ongepelde banaan, wat haar bijna fataal wordt zodat ze de Heimlich-manoeuvre met behulp van een stoelrug op zichzelf moet toepassen.

Oraal hoogtepunt is Mighty Aphrodite, waarin de call-girl Linda – een Oscar-rol van Mira Sorvino – haar klant Lenny Weinrib (Woody Allen) al snel doorziet: “You’re married, aren’t you?” “How can you tell?” “’Cause you got that look.” “What look is that?” “That look like it’s been a long time since you had a great blowjob.”

Hoewel hij haar kwaliteiten niet onderschat – “I’m sure you’re a state-of-the-art fellatrix” -, ziet Lenny af van haar diensten. In plaats daarvan schenkt Linda hem een – overigens foeilelijke – das, met de toelichting: “You didn’t want a blowjob so the least I could do is get you a tie.”

Schatplicht

Het is onvermijdelijk dat wie zijn plaats vindt in een bepaalde traditie aan zijn voorgangers in die traditie schatplichtig is. Zo ook Woody Allen. De voorbeelden liggen voor het opscheppen. Hij heeft er nooit een geheim van gemaakt dat hij een bewonderaar is van het werk van Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, de Marx Brothers, Jean Renoir en Luis Buñuel.

Voorall voor de Zweed, regisseur van onder meer Het zevende zegel (1957) en Wilde aardbeien (1957) heeft hij veel respect. In tal van Allens films zijn verwijzingen, zo u wilt stijlcitaten, naar Bergman-films te vinden, zoals de dood met de zeis in de hand in Love and death, een beeld dat Allen kende uit The seventh seal. Of de parallellen tussen Bergmans Cries and whispers (1972) en Alens Interiors (1978), die doorwerkten tot in de opstelling van de actrices. Onmiskenbaar is ook de gelijkenis tussen Smiles of a summer night (1955) en A Midsummer night’s sex comedy (1982).

Afgewisseld met lichter werk maakte Allen drie ernstiger films – Interiors, September (1987) en Another woman (1988) -, die als zijn meest Bergmanesqe maar niet bepaald zijn beste werken worden beschouwd. Niet geheel terecht, want zeker Interiors is een sterk en fraai vorm gegeven drama.

Maar bewondering voor iemand is nog geen beïnvloeding door iemand. Allen spreekt – voor zijn doen tamelijk vrijuit – over een aantal collega-regisseurs, maar ontkent met bijna verdachte hardnekkigheid de invloed die ze op zijn werk gehad zouden hebben. Een tekenend voorbeeld biedt de vergelijking tussen Sherlock Jr. (1924) van Buster Keaton en The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985).

Keaton (1895-1966) was de geniale alleskunner van de stomme film: hij schreef zijn eigen scenario’s, regisseerde zijn films, speelde er de hoofdrol in, deed zijn eigen stunts, wat hem een paar keer bijna fataal werd, en bedacht de ene fabuleuze visuele grap na de andere. In Sherlock Jr. droomt een jonge filmoperateur van zijn geliefde. In die droom betreedt hij de scène op het filmdoek en uiteindelijk maakt hij deel uit van de verwikkelingen in de film, een

voor de technische middelen die hem toen ten dienste stonden knappe prestatie.

Mia Farrow speelt in ‘Purple Rose’ een zielig typeje, dat slechts afleiding van haar armoede en slechte huwelijk vindt in de bioscoopzaal waar the Purple Rose of Cairo draait. De hoofdrolspeler, die in de gaten heeft dat er één bezoekster wel erg vaak in de zaal zit, komt van het doek af, begint een soort affaire met haar en neemt haar ten slotte mee terug, zijn filmwereld in.

Iedereen, behalve Allen zelf, ziet waar hij deze vondst vandaan heeft. In Woody Allen on Woody Allen (1993), waarin de Zweedse filmjournalist Stig Björkman hem interviewt over alle tot dan verschenen films, reageert Allen op de vraag of Sherlock Jr. op welke wijze dan ook een inspiratie voor ‘the Purple Rose’ was, enigszins geërgerd:

”Het was op geen enkele manier een inspiratie. (..) Ik was een verhaal aan het schrijven slechts gebaseerd op dit idee: dat het ideaalbeeld van een vrouw van het scherm af komt en zij verliefd op hem wordt, en dan verschijnt de echte acteur en moet zij kiezen tussen werkelijkheid en fantasie. En natuurlijk kun je niet voor fantasie kiezen, want dat kan tot krankzinnigheid leiden, dus moet je voor de realiteit kiezen. En als je realiteit kiest, word je gekwetst. Zo simpel is het. (..) Ik heb de film van Buster Keaton misschien 25 jaar geleden gezien. Het had niets te maken met mijn verhaal.”

En zo zijn er meer voorbeelden. Stardust Memories (1980) doet wel erg sterk denken aan Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963) zoals ook Celebrity en Radio Days opvallend veel trekken vertonen van respectievelijk La dolce vita (1960) en Amarcord (1973), beide van Fellini.

En zo zijn er meer voorbeelden. Stardust Memories (1980) doet wel erg sterk denken aan Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963) zoals ook Celebrity en Radio Days opvallend veel trekken vertonen van respectievelijk La dolce vita (1960) en Amarcord (1973), beide van Fellini.

De middelmatige komedie Small time crooks (2000) kent zelfs twee voorgangers. Het verhaal van een bende domme boeven die een pand huren om van daaruit de ernaast gelegen bank te kunnen binnendringen, werd in 1942 al verfilmd in Larceny Inc. De Italiaanse film I soliti ignoti (in Amerika Big deal on Madonna Street geheten) uit 1958 baseerde zich ook al op dezelfde premisse. En wie nog verder teruggaat in de tijd, vindt ook nog overeenkomsten met het Sherlock Holmes-verhaal The red-headed league van Sir Arthur Conan Doyle uit 1891. Maar hij put niet slechts uit andermans werk, ook zijn eigen oeuvre dient als bron. Niet alleen hergebruikt hij zijn materiaal – behalve Play it again, Sam is ook Shadows and fog voortgekomen uit een toneelstuk, de eenakter, Death –, hij herhaalt ook zichzelf.

In Another woman hoort een vrouw via een luchtschacht de gesprekken tussen haar buurvrouw, een psychiater, en haar cliënte, conversaties die haar dwingen terug te kijken op de successen en vooral de mislukkingen in haar eigen leven. Die kunstgreep herhaalt hij in Everyone says I love you (1996), wanneer Allens dochter de therapiesessies afluistert tussen haar moeder en een cliënte, Vonnie, gespeeld door Julia Roberts. Door een onbevattelijk toeval komen vader en dochter dezelfde Vonnie weinig later tegen in Venetië. Vader wordt verliefd op haar en dochter kan hem precies vertellen wat hij moet zeggen om haar te veroveren. Niet de sterkste plotwending in zijn oeuvre.

Zo past hij meer van zulke narratieve noodgrepen toe om het verhaal, al is het nog zo schoksgewijs, voort te helpen. Zijn favoriete truc lijkt de goochelaar-hypnotiseur te zijn. Die treedt al in Shadows and fog op, wanneer de circusartiest Armstead the Magician aan het eind van de film de hoofdpersoon, Kleinman, via spiegels laat verdwijnen en hem daarmee van de dood redt.

In The curse of the jade scorpion (2001) brengt een hypnotiseur de twee hoofdrolspelers – Woody Allen en Helen Hunt – beurtelings onder zijn invloed, wat niet alleen amoureuze maar ook criminele gevolgen heeft. In Magic in the moonlight (2014) moet Colin Firth een bedriegende goochelaar-annex-medium ontmaskeren. En ook in Stardust Memories en Broadway Danny Rose (1984) wordt er lustig maar met wisselend succes op los gegoocheld.

Het vermakelijkste voorbeeld is Oedipus wrecks (1989), Allens deel van het drieluik New York Stories (1989); de andere twee delen zijn van Martin Scorsese en Francis Ford Coppola.

In zijn bijdrage ziet Allen zijn moeder, een heerlijke rol van Mae Questel, in een verdwijnkast stappen en ziet hij haar pas terug als wolk aan de hemel, die commentaar geeft op zijn keuze voor een niet-joods meisje. Nog een opmerkelijke kunstgreep is te zien in Alice, als de hoofdpersoon – Mia Farrow – van een Chinese wonderdokter kruiden krijgt die haar onzichtbaar maken. Helaas slechts tijdelijk, wat nog tot pijnlijke complicaties leidt als ze weer zichtbaar wordt terwijl ze haar man op overspel aan het betrappen is.

In Scoop stapt de studente Sondra Pransky – Scarlett Johansson – als vrijwilligster in de verdwijnkast, de Dematerializer, van The Great Splendini. Daar komt zij in contact met gene zijde, alwaar zij informatie krijgt over de identiteit van een seriemoordenaar. Het is de eerste en enige keer dat Allen zelf de rol van de goochelaar speelt.

Techniek en thematiek

Wie gemiddeld één film per jaar aflevert, mag op z’n minst voor enige variatie in de vormgeving zorgen. En dat doet Woody Allen. Naast al die films die zich alleen maar in de betere kringen van New Yorks Upper East Side lijken af te spelen – Annie Hall, Alice, Hannah and her sisters -, heeft hij vaak geprobeerd een originele vorm voor de vertelling te vinden, of ten minste een variant op een bestaande vorm.

Zo is Everyone says I love you een vette knipoog naar de musicalfilm, waarin op de meest onverwachte momenten de acteurs aan een nummer uit The Great American Songbook beginnen (met als discutabele bonus dat we ook Julia Roberts en Woody Allen zelf een stukje horen zingen). ‘Take the money’ en Zelig hebben de vorm van een documentaire, inclusief nieuwsfragmenten en interviews met familieleden en deskundigen.

Zo is Everyone says I love you een vette knipoog naar de musicalfilm, waarin op de meest onverwachte momenten de acteurs aan een nummer uit The Great American Songbook beginnen (met als discutabele bonus dat we ook Julia Roberts en Woody Allen zelf een stukje horen zingen). ‘Take the money’ en Zelig hebben de vorm van een documentaire, inclusief nieuwsfragmenten en interviews met familieleden en deskundigen.

Shadows and fog is een prachtige hommage aan M – eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder, het meesterwerk van Fritz Lang uit 1939. Het is het in hard zwart-wit gefilmd verhaal over een moordenaar die volgens geruchten rondwaart, gesitueerd in een onduidelijke Oost-Europese stad in de jaren 30, met een kafkaësque beklemmende anonieme dreiging en Allen in een overtuigende rol met de veelzeggende naam Kleinman. Het is Allens enige film die geheel in een studio werd opgenomen.

En Mighty Aphrodite is helemaal opgebouwd als een Grieks drama, inclusief Tiresias de blinde ziener, de immer onheil voorspellende Cassandra, een koor van schikgodinnen en een deus ex machina in de vorm van een helikopter die in de wei landt.

Nog zo’n reputatie: Allen heet een vrouwenregisseur te zijn. Niet ten onrechte, want van de negen Oscars voor beste hoofd- of bijrol die zijn films opleverden, was er maar één voor een man: Michael Caine in Hannah and her sisters. Allen zelf heeft het als acteur nooit verder gebracht dan de nominatie voor beste mannelijke hoofdrol in Annie Hall. Hij moest het toen opnemen tegen Marcello Mastroanni (Una giornata particolare), Richard Burton (Equus) en John Travolta (Saturday Night Fever), maar zij legden het allen af tegen Richard Dreyfuss in The goodbye-girl.

De overige acteur-Oscars waren voor Diane Keaton (Annie Hall), Diana Wiest (Hannah and her sisters en Bullets over Broadway), Mira Sorvino (Mighty Aphrodite), Penelope Cruz (Vicky Christina Barcelona) en Cate Blanchett (Blue Jasmine). Waarbij opvalt, dat – op die voor Keaton en Blanchett na – het alle Oscars voor beste bijrol waren.

Nog merkwaardiger is, dat Judy Davis, bij uitstek de vrouwelijke neurotische tegenhanger van de “Woody”, voor haar vier films al met al maar één nominatie verdiende, voor Husbands and wives. Maar het opmerkelijkst is zonder twijfel dat Mia Farrow, die tussen 1982 en 1992 in dertien Allen-films de vrouwelijke hoofdrol speelde, niet één nominatie verwierf, laat staan een Oscar.

Ethisch dilemma

Allen heeft ook de naam de filosoof onder de filmregisseurs te zijn. Schijnbaar existentiële levensvragen stelt hij zich door zijn hele werk heen, te beginnen met Love and death. Een even representatief als ondoorgrondelijk citaat daaruit is deze hartenkreet van Boris Grushenko, gespeeld door Allen: “To love is to suffer. To avoid suffering one must not love, but then one suffers from not loving. Therefore, to love is to suffer, not to love is to suffer, to suffer is to suffer. To be happy is to love, to be happy then is to suffer but suffering makes one unhappy, therefore to be unhappy one must love or love to suffer or suffer from too much happiness.”

Timothy Holland somt die levenskwesties op in een essay over Shadows and fog, die hij the quintessential Woody Allen movie, de kern van zijn werk, noemt: “the absence of God, the alienation of man, and the search for meaning – through art, science, philosophy, religion, sex, love, and family – in a seemingly godless world” (de afwezigheid van God, de vervreemding van de mens en het zoeken naar zin – door kunst, wetenschap, filosofie, religie, seks, liefde en familie – in een ogenschijnlijk goddeloze wereld).

Er verscheen zelfs een essaybundel, Woody Allen and Philosophy, een eer die gerelativeerd wordt door enkele van de andere titels in deze reeks, zoals Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Philosophy of Harry Potter and Philosophy.

Die reputatie als filosoof is maar ten dele terecht. Om te beginnen zijn zulke vragen, mits ruim genoeg geformuleerd, van toepassing op alle serieuze kunst, de literatuur niet in het minst. Daar komt bij, dat hij vrijwel elke ernstig lijkende uitspraak met een kwinkslag weer onderuit haalt. Een bekend voorbeeld: “Niet alleen bestaat er geen God, maar probeer maar eens op zondag een loodgieter te krijgen”.

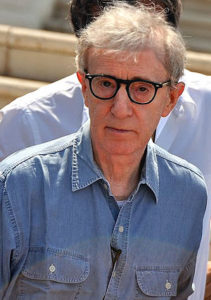

Woody Allen Foto: ia.wikipedia.org

Belangrijker dan dat is dat Allen, op meer of minder vermakelijke wijze, wel tal van vragen stelt maar nooit een antwoord biedt. Er is echter een thema, dat als typerend voor Allen kan worden beschouwd: het ethisch dilemma of, in zijn eigen woorden, een moral topic, het spanningsveld tussen het normale morele besef – iedereen zal in principe moord en andere zware misdaad afwijzen – en de vraag wanneer en met welke rechtvaardiging die grenzen overschreden kunnen worden.

Allen stelt deze kwestie aan de orde in Matchpoint (2005), Cassandra’s Dream (2007) en Irrational man (2015), maar het scherpst van al in Crimes and misdemeanors. Daarin wordt de oogspecialist Judah Rosenthal door zijn minnares gedwongen zijn vrouw over hun relatie in te lichten, anders doet ze het zelf wel. Hij bespreekt het probleem met zijn broer, een gangster, die wel een oplossing heeft, een heel definitieve oplossing. De wroeging die Judah hier aanvankelijk over voelt, is slechts tijdelijk. In Matchpoint speelt een soortgelijk conflict: de ambitieuze maar arme tennisleraar Chris Wilton heeft zich net de betere kringen binnengetrouwd, maar ziet zijn mooie leventje bedreigd als zijn minnares zwanger van hem blijkt te zijn. Dat hij om zijn luxe bestaan te redden niet alleen de minnares maar en passant ook een volstrekt onschuldige buurvrouw moet vermoorden, stelt het dilemma alleen nog maar helderder.

Cassandra’s Dream gaat over twee broers die meer ambitie dan geld hebben – de titel is de naam van de boot die ze willen kopen -, tot hun oom die droom mogelijk maakt. Maar daar staat wel wat tegenover: een zakelijke concurrent van oom dient uit de weg geruimd.

Al deze voorbeelden zijn geïnspireerd door het centrale thema in Dostojevski’s Misdaad en straf (1866): de vraag of, en zo ja onder welke omstandigheden, er een rechtvaardiging voor een bepaalde daad of keuze te bedenken is, bijvoorbeeld voor een moord. In Dostojevski’s roman vermoordt de student Rodion Raskolnikov de oude vrouw van wie hij tegen woekerrente geld geleend heeft dat hij niet kan terugbetalen. Dat hij de zuster van het slachtoffer, die hem betrapt heeft, ook moet doden, is een van een aantal parallellen tussen Misdaad en straf en Matchpoint. De student rechtvaardigt zijn daden met de theorie, dat hij tot een beter soort mens hoort, in tegenstelling tot de woekeraarster, en dat dit hem het recht geeft tot moorden.

Lijkt de arme maar intelligente Wilton in Matchpoint al op Raskolnikov, diens ware eigentijdse personificatie is de gewetenloze Abe in Irrational man, getuige zijn uitspraak “I’m Abe Lucas and I’ murdered. I’ve had many experiences and now a unique one. I’ve taken a human life. Not in battle or self defense, but I made a choice I believed in and saw it through. I feel like an authentic human being.”

Deze moorden vinden plaats in een film, in een theoretische, een fictionele en dus voor Allen veilige situatie. Zijn werkelijke ethisch dilemma zou moeten luiden: is het moreel acceptabel een relatie te beginnen met je pleegkind, dat al jaren deel uit maakt van je gezin, ook al is ze meerderjarig en stemt ze met het contact in, en is ze biologisch gezien niet je nageslacht?

Maar die morele kwestie komt in géén van die 50 films aan de orde.

–

Robert-Henk Zuidinga (1949) studeerde Nederlandse en Engelse Moderne Letterkunde aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Hij schrijft over literatuur, taal- en bij uitzondering – over film.

De drie delen Dit staat er bevatten de, volgens zijn eigen omschrijving, journalistieke nalatenschap van Zuidinga. De boeken zijn in eigen beheer uitgegeven. Belangstelling? Stuur een berichtje naarinfo@rozenbergquarterly.com – wij sturen uw bericht door naar de auteur.

Dit staat er 1. Columns over taal en literatuur. Haarlem 2016. ISBN 9789492563040

Dit staat er II, Artikelen en interviews over literatuur. Haarlem 2017. ISBN 9789492563248

Dit staat er III. Bijnamen en Nederlied. Buitenlied en film, Haarlem 2019. ISBN 97894925636637

Deze beschouwing over Woody Allen is gepubliceerd in deel III.

Fryslân DOK

Fryslân DOK