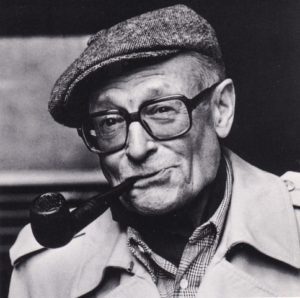

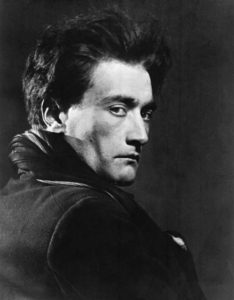

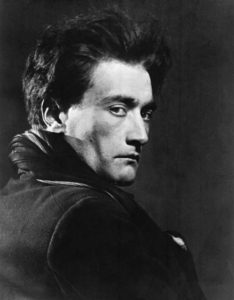

Antonin Artaud (1896-1948)

Abstract

Intrigued by the idea that the Islamic State’s media is performing Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, we questioned in this article whether Islamic State’s use of media does indeed compare to the hellish visions of the notorious French dramaturge, and consequently ask ourselves, if so, how we should interpret and give meaning to the eventual connection between two subjects that seem so far apart, and yet so close to each other: the Theatre of Cruelty and the gruesome religiously inspired videos of Islamic State.[i] The results of our analysis confirm significant parallels between the Theatre of Cruelty and the cruel videos of Islamic State. Considering the fact that the message of cruelty is central to many of their videos, we conclude that ‘Islamic State’s media productions indeed implement the characteristics underlying Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.’ But what does all this mean? Cruelty and violence are indeed elements of human being’s nature. Humankind has to embody it in one way or the other, and from that perspective, it is much better to incorporate these darker sides of men in the metaphysical sphere. We are deliberately speaking here of humankind, irrespective of religious or ethnic background, because there are Westerners and Easterners that have learnt this dear lesson: acknowledging the dark side of men and expressing it in art.

Key words: # Islamic State # Artaud # Theatre # Propaganda # Cruelty # Hermeneutics # Interpretation

1 Introduction

‘Artaud, a sickly child twisted further by the shock of World War I, wanted his actors to “assault the senses” of the audience, shocking parts of the psyche that other theatrical methods had failed to reach. Well, IS has read the book. It’s been obvious since September 11 that we’re living in an age of vicious political theatre. That’s what ‘terrorism’ is: the manipulation of large populations by shock and awe and ‘liberating unconscious emotions’’ (to quote Artaud).’[ii]

‘If the attacks on the Twin Towers used the iconography of the Hollywood action blockbuster, the beheadings in the desert evoke drama far more ancient – Old Testament strife, Hellenic legend. [..]It may sound unlikely, but ISIS is carrying out in extremis the program of the ‘Theatre of cruelty’ of the influential French dramaturgedemiurge Antonin Artaud.’[iii]

In the summer of 2014, the geopolitical stage was shaken by the Islamic State videos. Starting off a series of terrifying communiqués with a video of the beheading of journalist James Foley in A message to America, Islamic State quickly set a new standard for extremists’ use of media as a propaganda tool. Now that the extreme display of violence has become the hallmark of Islamic State terror, certain journalists have suggested a link between these brutal videos and dramatist Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) and his ‘Theatre of Cruelty’. We were intrigued by the idea that the correspondence between Islamic State’s media outlets and Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty might actually go beyond the shared predominance of cruelty and have taken the suggestion made by Sakurai as a cue to research whether Islamic State’s use of media does indeed compare to Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty on a more fundamental level. And consequently ask ourselves how, if so, we should interpret and give meaning to the eventual connection between two subjects that seem so far apart, and yet so close to each other: the Theatre of Cruelty and the gruesome religiously inspired videos of Islamic State.

The research done is comparative in nature. By comparing and contrasting the principal underlying ideas, the audience/performance relation, and the performance itself of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty and Islamic State’s video productions, we hope to arrive at a detailed and nuanced understanding if and if yes, how Islamic State and Artaudian theatre relate to each other. The possible connection between both being eventually confirmed, we will consequently dwell on the meaning of such connection.

The article is accordingly structured: Section one details our hypothesis and research method. Section two discusses Islamic State media. Section three discusses Artaudian thought. In section four, we analyze IS media through Artaudian thought. Section five recapitulates our findings, which lead to a conclusion and discussion.

Hypothesis and methodology

‘The full body of Islamic State propaganda is vast’, writes Winter[iv], and we might add to that that it is diverse. It is a misunderstanding that all of the IS media products are characterized by violence and cruelty; there are also ‘peaceful’ ones presenting the paradise that the Caliphate would be. Still, inspired by the quotes mentioned above we focus on the cruel ones and their relationship with Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty. Our hypothesis in researching this is the following:

Islamic State’s media productions implement the characteristics underlying Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.

To test this hypothesis, we concentrate on three elementary domains of the theatre as distinguished in literature on the subject[v][vi]: (1) the central ideas behind the performance, (2) the audience/performance relationship, and (3) the performance itself. They result in the following research questions:

RQ1: Do the ideas behind Islamic State media productions compare to Artaud’s ideas on the theatre?

RQ2: Does the audience/performance relation in Islamic State media productions compare to Artaud’s?

RQ3: Does the performance of Islamic State media productions compare to the Artaudian performance?

We will answer our hypothesis and research questions by operationalizing a case study. By comparing and contrasting crucial elements typical of each in the domains in question, a decision is made based on whether the similarities outweigh the differences, or vice versa. The validity of the hypothesis will subsequently be judged on the basis of the cumulative presence or absence of substantiating elements in the outcomes of the three research questions investigated.

Islamic State Media

In this section, we first explain the vision of IS on media. Subsequently, we discuss the IS media/audience relation. Finally, we discuss the video Although the Disbelievers Dislike It, the present case study.

2.1 A vision on media

In Islamic State’s goals to establish a caliphate, one work in particular has become influential in its strategy: The Management of Savagery, by alleged al-Qaeda strategist Abu Bakr Naji[vii]. The Management of Savagery attempts to improve on Jihadi operations by pointing out the mismanagement of resources, recruits and violence in previous Jihadi movements.

Naji[viii] emphasizes that an effective use of media in the Jihadi movement’s strategy is imperative for achieving success in Jihadi operations. The objective is to create a media strategy functioning on two levels, civil and military, in order to create an appeal to the masses to join the jihad, to create a negative attitude toward those who do not join the ranks, and to convince enemy troops to abandon service or join the ranks through a monetary incentive or physical threat. This media strategy should especially, but not exclusively, target at recruiting the youth, ‘after news of our transparency and truthfulness’, seeking ‘rational and sharia justification’ to add power to the message and expose the enemies’ lies[ix].

There is a clear dichotomy in Naji’s vision on media. On the one hand, he criticizes the abusive reports in the media issued by the superpowers, stating they are deceptive and obfuscate the masses. On the other hand, he admits the necessity of pursuing a media strategy in creating the Umma, the ideal of an all-encompassing Islamic world, using ‘rational and sharia justification’[x] to win over the hearts and minds of the masses:

‘Therefore, this important point should not be ignored, especially since we want to communicate our sharia, military, and political positions to the people clearly and justify them rationally and through the sharia and (show that) they are in the (best) interest of the Umma’.[xi]

Looking at Islamic State’s media strategy, the similarities between Naji’s vision on media and IS’s implementation of propaganda become strikingly clear. Broadly speaking, IS propaganda is meant to serve two different purposes: the first is recruitment, focusing on the utopian appeal of the Caliphate; the second is to intimidate, scare and threaten opponents[xii].

In The Management of Savagery, Naji emphasizes the power of the masses, and the need to harness this power in order to enhance the Umma[xiii]. Islamic State endorses this idea by planning its propaganda strategies in such a way that the message will reach as large a (Western) audience as possible. To reach their audience, IS focuses heavily on social media as means of communication. Naji’s strategy involves targeting the youth in particular, who, are strongly represented on the Internet. On its ideas regarding the use of media to demoralize the enemy[xiv], Islamic State finds a like-minded counterpart in the Western media. Propaganda aimed at menacing and intimidating governments and populations is equally abundant in the various Western media outlets. Winter attributes this to the nature of commercialized news institutes: ‘After all, fear sells’[xv]. Although the use of social media is not new for jihadist groups, IS is noted as setting ‘the gold standard for propaganda in terms of its quality and quantity’[xvi].

2.2 Although the Disbelievers Dislike It

Out of the vast number of videos IS has produced so far, we opted in our present study for the video Although the Disbelievers Dislike It, which was published on the 13th of November of 2014. As can be deduced from the quotes of Jones and Sakurai above, -cruel- IS video productions would allegedly have been created in the vein of the Theatre of Cruelty. As an analysis of all IS video productions is virtually impossible, and considering the fact that the message of cruelty is central to many of their videos, considering moreover that Although the Disbelievers Dislike appears to be targeted particularly at a Western audience – after all, are not most Westerners disbelievers (‘infidels’)?- and last but not least since it prominently features Western believer ‘Jihadi John’, we opted for this video for making our case. Furthermore, it is important to mention that the video has been the object of earlier analysis by Winter[xvii].

In this section, we present a summary of a detailed analysis of the video. The title of the video is an excerpt from the Quran, chapter 9, verse 32[xviii]:

‘They want to extinguish the light of Allah with their mouths, but Allah refuses except to perfect His light, although the disbelievers dislike it.’

The video, with a runtime of 15m53, consists of five different segments[xix]: The first shows a map moving in time, displaying claimed territory and regions with official IS affiliates, followed by countries that IS is aiming to expand into. The second segment presents a documentary-style narrative, summarizing the rise of IS. The third segment shows IS fighters, parading twenty-two ‘Nusayri’ prisoners (term used to refer to the Alawite or Shiite regime of Syrian President Assad and its supporters) through an olive grove past a box of knives, concluding with their simultaneous execution. The fourth segment returns to the map, highlighting countries in which jihadist groups pledge allegiance to the caliph of Islamic State, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. The fifth and final segment shows a clip of the allegedly British ‘Jihadi John’ with the severed head of American aid worker Peter Kassig, followed by a short speech by ‘Jihadi John’, addressing president Obama.

In discussing the video, Winter observes that ‘In […] Although the Disbelievers Dislike It, IS attempts to provide a graphic cinema-quality experience to its viewers, something which, at first sight, it succeeds in achieving.’[xx] This experience is achieved through the use of several dramatic elements. These elements are animation, dramatic sound effects, the use of non-instrumental religious songs – ‘Anasheed’ in Arabic-, the use of a documentary-style[xxi] narrative accompanied by graphic – ‘Hollywood- Style’ – war imagery, symbolism of the flag, slow-motion effects, dramatic facial shots, orchestrated ‘acting’, immersion of the audience through multiple camera angles[xxii] and the display of violence.

In the video, symbolic imagery is used resembling Western iconography and popular culture. The ‘son of Islam’[xxiii], who is striding forth, carrying the Islamic State flag, is an image strikingly similar to the iconic photograph of American soldiers raising the flag over Iwo Jima during World War II. The footage of warfare and the use of the first-person perspective[xxiv] are reminiscent of video games like Call of Duty. It presents the IS narrative in a local context, but is highly recognizable for foreign audiences. Furthermore, the video includes numerous displays of symbolism referring to Islamic scripture. For example: After the mass execution of the twenty-two ‘Nusayri’ soldiers, their heads are displayed on top of their bodies lying on the ground[xxv]. Watching the video, one cannot help but conclude one is witnessing a carefully staged event of cruelty intended to scare and horrify, fully thought through in content and structure for maximum effect.

The Theatre of Cruelty

In this section, we discuss Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.

3.1 Artaud and His Doubles

The life and (theatrical) writings of French avant-gardist, dramatist, and theorist Antonin Artaud have sparked the imagination of many artists and critics. His ideas were theorized by thinkers like Susan Sontag (1973) and Jacques Derrida (2002), who made a dominant mark on understanding Artaud, by interpreting his work against the backdrop of a 1960s leftist and experimental period of the Theatre. However, as Jannarone rightfully argues in her publication Artaud and his Doubles (2012), the sentiment of the masses and the political settings of this post-World War II era were different from the period in which Artaud wrote down his ideas, making their and others’ interpretation of his work ‘inadequate, if not inappropriate’[xxvi]. This prompted Jannarone to re-examine the writings and ideas of Artaud, situating and interpreting them in a historically appropriate context. Rather than including the character and rather manic personal life of Artaud in evaluating his work, as many had done before her, Jannarone restricted herself to examining his plays and writings, which resulted in a take on his work radically different from previous interpretations.

3.2 Central ideas of the Artaudian Theatre

Antonin Artaud articulated his central ideas on the Theatre in his work Le Théâtre et son double (1938[xxvii]), a collection of essays written between 1931 and 1935, resulting in his famous conceptual ‘Theatre of Cruelty’. The delusion caused by World War I constituted a fierce and ‘climactic articulation’, of irrationalist and vitalist thought originating at the turn of the twentieth century, which now backfired on itself as its optimistic and progressive liberal views on human nature were discredited in this outburst of violence. Although the avant-garde movement sought to bring about the destruction of existing systems, their intentions were predominantly utopian. Artaud, however, rejects the idea of utopia, and instead longs for an ideal of ‘true culture’, as he believed that traditions, art, and received ideas only represent the stagnation of ‘true culture’. In a sense, he longs for a primordial form of culture, an encounter with forces akin to those featuring in the life and character of the brutal Dionysus in Euripides’ Bacchae. Characteristic of Artaudian thought is the inversion of the aspirations of Western civilization, and the eulogization of their negations.

Artaud uses the plague in the first essay, The Theatre and the Plague, in his The Theatre and its Double as a central metaphor in his ideal theatre, implying that the theatrical event should have a force equal to that of a plague terrifying the city, a physical, cruel cataclysmic event with the power to overthrow man-made systems and return him to a state of nature and mysticism. The metaphor of the plague essentially serves as an instrument for the destruction of corruption. However, ‘the plague used as a model for theatre, does not cure in any recognizable sense: it only unleashes’[xxviii]. The theatre envisioned by Artaud, as Jannarone suggests, is an unacknowledged repetition of the horrors of World War I, not climaxing into a victory, but rather into a perversion of victory. In Artaud’s theatre, there is truly no such place as a man-made utopia[xxix]. Traumatized by the disenchanting outcome of World War I, Artaud proposed a theatre aimed at destroying man-made systems in search of a ‘true culture’, void of corruptions. He calls for a physical, cruel action to happen to force man back to a state of ‘savage impulses’, ‘bestial essences’, where he is driven by ‘the secret forces of the universe’, rather than individual intellect and the pursuit of civilization[xxx].

3.3 The Audience in Artaudian theatre

During the 19th century, the audience’s role in the theatre had become that of a domesticated, hidden bystander. In theatrical theory, this phenomenon has become known as the ‘crisis of bourgeois theatre’; technological and social developments led to a ‘stable hierarchy in the performance, enforced physical behavior and immersion’ within the theatre. This resulted in one single rule: ‘The audience will behave’. Reactionary, the avant-garde movement adopted ideas that opposed these controlling factors while agitating and activating the audience[xxxi].

Artaud’s writings on the subject of the audience incorporate ideas from pre-war 20th century as well as avant-garde movements: while ushering in a rhetoric of revolt and agitation found in the avant-garde movement, and dismissing the strict rules of separation between the audience and the performance as perverse. He also incorporated several innovations from the bourgeois theatre: He used technological innovations to bring about a stronger immersive experience, while sticking to the tradition of hierarchy in relation to the performance. His manifestos advocate ‘organized anarchy’, which, as Jannarone[xxxii] observes, ‘points to the unique dynamic at the heart of the Theatre of Cruelty’s ideal audience/performer relationship.’ Pure anarchy is considered decadent, operating ‘outside and irrespective of higher laws’[xxxiii]. With respect to the controlling forces of nature, Artaud in his Theatre of Cruelty aims both at agitation and control: an orchestrated breakdown of feelings and boundaries within a ‘predetermined structure’[xxxiv].

In conclusion, the audience in the Theatre of Cruelty holds a unique position in between major theatrical movements, containing elements from the bourgeois theatre’s innovations as well as elements from the avant-garde movement. These elements converge into an audience/performance relation called ‘organized anarchy’, through which the audience is thrown into savagery by means of an orchestrated structure.

3.4 The Theatre of Cruelty

The practical performance Artaud had in mind combined his ideas on society with those he held on the psychology of the individual, and was aimed at dislodging his audience, freeing them from society’s chains and directing them toward a natural state of being through a cruel liberator. He first put his radical theatrical theories into practice during the period in which he ran the Jarry Theatre (1926-1928), and finally in his last theatrical work, the adaptation of The Cenci (1935), which turned out to be a fiasco due to financial mismanagement and aesthetic failure. As a result of his troubled realization of the Theatre of Cruelty, Artaud retreated into the solitude of theoretical writing.

Examining Artaud’s period as a stage director gives insight into the practical performance derived from his ideas. The performance of the Theatre of Cruelty is a ‘one directional event, a system of control and coercion‘[xxxv], an instrument that imposes the creator’s worldview on his audience as an experience. The director, as the artistic authority, has absolute control over the performance, abandoning other sources of authority such as the playwright. His inspiration works ‘outside of existing laws and is uniquely capable of negotiating between the material world and the invisible one.’[xxxvi] This resulted in a shift from the use of playwrights and their scripts toward production plans, thus severely reducing the influence of given texts. The production plan would function as a basis for performance, replacing fully written-out scripts. The artist’s objective is to represent the ‘spirit’ of a text, rather than render a literal representation of it.

Practical elements in the mise-en-scène of the Theatre of Cruelty, should consist of ‘abrupt changes of tone and rhythms; mysterious doubles of characters; echoes and amplifications of sound; slow-motion; alternately blinding, mysterious, and shadowy lightning effects; and skewed set pieces’[xxxvii]. The stage in the Jarry Theatre was decorated with fear-invoking props.

The Artaudian theatre and Islamic State media compared

In this section, we present a detailed comparison of Islamic State media, in particular the video Although the Disbelievers Dislike It, and the ideas of Antonin Artaud.

4.1 Central ideas

One of the main objectives in Islamic State propaganda, is achieving a state of savagery in (un)friendly territory[xxxviii]. In unbalancing the existing powers lies the opportunity of incorporating such territories in the Umma. Instrumental in this plan, is the use of media to expose the enemies’ ‘deceptive media halo’, through ‘rational thought and sharia law’. Naji[xxxix] (2006) proposes a counter-mechanism acting against established beliefs. There are three aspects to be considered in his proposed use of media: the use of ‘rational arguments and sharia law’ as justification for Jihadi operations; a liberating action against opposing forces who abide by other ideals, and the utopian goal of founding the Umma. In comparing and contrasting these with Artaudian ideas, we find they have elements in common with each other. The ideas of Artaud being traumatized by World War I, were strictly anti-establishment. He describes his concerns on civilization in Le Théâtre et son double (1938) as follows:

‘Never before, when it is life itself that is in question, has there been so much talk of civilization and culture. And there is a curious parallel between this generalized collapse of life at the root of our present demoralization and our concern for a culture which has never been coincident with life, which in fact has been devised to tyrannize over life’[xl].

Artaud denounces civilization and culture as a tyrannizing force acting upon the nature of life. Instead he opts for a primordial ideal where man is in alignment with his true nature and in contact with the mysterious forces surrounding him. Artaud thus subscribes to universal principles of life, opposed by man’s attempts to reach a civilized world. In a similar fashion, Naji rejects the existing powers, and points towards a ‘universal law, which is also sharia law’[xli]. There is a striking similarity between Islamic State ideology and Artaudian thought. They both refer to a system of universal laws that both believe to be of divine origin. Or, in the words of Artaud:

‘If our life lacks brimstone, i.e., a constant magic, it is because we choose to observe our acts and lose ourselves in considerations of their imagined form instead of being impelled by their force. … And this faculty is an exclusively human one. I would even say that it is this infection of the human which contaminates ideas that should have remained divine; for far from believing that man invented the supernatural and the divine, I think it is man’s age-old intervention which has ultimately corrupted the divine within him.’[xlii]

In his interpretation of what it is that constitutes the divine, Artaud makes a strong distinction between ‘modern’ monotheism and ancient naturalistic religions:

‘The Conquest of Mexico poses the question of colonization. It revives in a brutal and implacable way the ever-active fatuousness of Europe. It permits her idea of her own superiority to be deflated. It contrasts Christianity with much older religions. It corrects the false conceptions the Occident has somehow formed concerning paganism and certain natural religions, and it underlines with burning emotion the splendor and forever immediate poetry of the old metaphysical sources on which these religions are built.’[xliii]

Artaud refers to paganism: old metaphysical sources rejected by Christianity. Paganism in Islamic State ideology is considered sinful. A clear example of this can be found in the denunciation of what is happening ‘these days in the city of Baghdad’, which IS caliph al-Baghdadi comments on[xliv]. He accuses the (Shiite; considered the worst of enemies of IS) Baghdad government in charge at the time of this statement of being guilty of apostasy. While Artaud underlines elements of ‘immediate poetry’ through ‘metaphysical sources’, such liberties of religious interpretation are limited in Islamic State ideology. However, what Artaud and IS are both trying to accomplish, is to bring about a state of purity of man, going back either to metaphysical sources, in the case of Artaud, or to holy scriptures, in the case of Islamic State.

Artaud’s invocation of the plague[xlv] serves as a metaphor for a necessary destructive force, which should ring and rage through the theatre to liberate its audiences from the clutches of society. A similar approach can be found in Naji’s proposed media strategies[xlvi], where he suggests fear[xlvii] as an instrument to destabilize regions into a state of savagery. The ultimate goal of such tactics in Naji’s work is to incorporate these regions into the Umma. The important element both ideas have in common is the incorporation of (the fear of) destruction as a liberating force in the existing societal structure.

The ideas of Antonin Artaud, in their original conception, were nihilistic. Jannarone describes the ferociousness of Araud’s writings as a ‘fight for impossible absolutes’[xlviii]. The ideal of a life where all hypocrisy that flows forth from the act of civilization is brutally discarded in favor of a deeper, divine nature. In a very similar way, Islamic State adheres to the creation of a world-encompassing Islamic State that rejects any form of civilization other than the historical version of the Caliphate, a jihadist state that is governed by the purest form of Islam [xlix].

In conclusion we can say that Naji proposes three objectives for a media apparatus. Although the first goal – imposing the idealism of the rational and sharia law – closely resembles an Artaudian ideal, it should be stressed that Artaud envisions this source as far more naturalistic and chaotic. The second objective shows striking similarities with Artaudian ideas: the act of liberation through cruelty; a necessity in the deconstruction of a faulty or hostile order. The third objective, the foundation of the Umma shows paradoxical similarities with Artaud’s ‘true culture’. While Artaud deems the realization of such a ‘true culture’ an ‘impossible absolute’, the supporters of Islamic State wholeheartedly believe in it, and therefore fight for its realization. Now these two visions seem to contradict each other. But IS’s firm belief in realizing the dreamed Umma can be drawn into question, as more than once the ideologists of Islamic State have expressed their weakness in the eyes of God and stressed the fact that after all they are only human, and necessarily flawed as a result. We find this asserted more than once in the different volumes of the IS glossy Dabiq. An article in Dabiq 3, entitled Advice for those embarking upon Hijrah warns those intending to travel to the Caliphate to be realistic in their expectations:

‘Keep in mind that the Khilāfah is a state whose inhabitants and soldiers are human beings. They are not infallible angels’. ‘You may find some of your brothers with traits that need mending. But remember that the Khilāfah is at war with numerous kāfir states and their allies, and this is something that requires the allotment of many resources. So be patient’[l].

In conclusion it can be postulated that Artaud may have been closer to being conscious of the impossibility of the realization of his ‘true culture’ than Islamic State adherents are of their dreamed Umma. But the Dabiq quotes make it equally clear that the IS fighters are aware of their own weaknesses or should at least be aware of them. What seems quite clear in all cases is that both need the hand of the divine to realize their utopian goals and as such they show a striking similarity.

4.2 Performance – Audience relationship

The audience in Artaudian theatre holds a unique position in Theatre history. Plying the traditions of the avant-garde and bourgeois movements, Artaud set out to project an awakening experience onto his audiences. The two main characteristics of the relation between public and performance in his work are, firstly, the hierarchical structure of the play – the use of a ‘domesticated’ audience[li]. Secondly, Artaudian theatre wields an agitating rhetoric meant to break the barriers between an audience passively watching and the play at hand. The rhetorical action often worked against the integrity of Artaud’s performance. He thus chose to use the oxymoronic concept of ‘organized anarchy’[lii] to achieve the ideal relationship he envisioned with his audience.

When considering the audience to performance relationship in Islamic State’s media outlets, a few elements can be picked out that deserve analysis against the background of Artaudian and avant-garde theatre. Firstly, there is the specific imaginary relying, heavily on the war-narrative, depicting combat, brutality and victories achieved by Islamic State. It is reminiscent of the rhetoric used in Artaudian fashion – the performance either being a threat to and provocation of a supposedly hostile audience, or acting as a liberator for those who are oppressed by societal structures, motivating the audience to sympathize with Islamic State and thereby also serving as a recruitment tool. As Jannarone observes, Artaud (in his rhetoric) uses the trope of shock as an instrument of punishment rather than provocation[liii]. In contrast to avant-garde dramatists, and Brechtian theatre for example, the aim is not to challenge the audience into political and intellectual engagement. The aim in the Theatre of Cruelty is ‘the exploration of our nervous sensibility’.[liv] Here we are confronted with what appears to be a clear difference between Artaudian theatre and Islamic State’s media productions. Although a very similar rhetoric and shock effect is apparent in IS’s cruel videos, they also contain elements that propagate activist engagement from a jihadist perspective.

On the relative distance of the audience in relation to the performance, a similarity can be observed between the behavior of modern audiences and the avant-garde audience. As the permanent establishment of the bourgeois social class took place, the theatre transmuted from a common people’s institute to a commodity of refinement[lv], turning the audience into ‘domesticated’ observants rather than a crowd involved in the performance. The avant-garde movement reacted to this phenomenon and fought audience conventions by either shock or reason[lvi]. They chose to ‘engage’ their audience (as in Brechtian political theatre, for instance). A strong similarity can be observed when we compare this to contemporary 21st-century pre- and post-social media audiences and their ability to interact with a performance. As Winter observes[lvii], ‘the Internet is the modern Jihad’s radical mosque’, and it is now possible for audiences anywhere to interact with members and proponents of Islamic State. The Artaudian approach embellishes ideas of bourgeois theatre in that it propagates hierarchy within the audience-performance relation in order to ‘assert the performance’s authority over the spectators’[lviii]. It is here that the subtle difference lies between Artaud and other avant-garde dramatists, as Artaud does not specifically ask his audience to engage, he rather seeks to achieve ‘an orchestration of the feeling of breaking boundaries within a predetermined structure’[lix]. It becomes apparent that, although Artaud also seeks to break down the barrier between a bourgeois audience and the play, he utilizes the audience to performance relationship in a one directional, non-dialogical way. Even though Islamic State media are intended to actively stimulate engagement and deliberation, the rhetoric of Islamic State itself can be considered to be non-dialogic as well, using as it does Islamic scripture as a foundation for IS actions. Thus, for example, in Although the Disbelievers Dislike It, caliph Al-Baghdadi cites Imam Malik, founder of the Sunni school of the Malikites, on the rise of the ‘Rafida’ (‘rejecters’; IS terminology to refer to the Shiites) in the city of Baghdad: ‘One must not remain in a land in which Abu Bakr and Omar are insulted[lx]’. (05:08) Using this citation, he urges the devout to relocate to lands where Abu Bakr and Omar are not insulted with the ‘would-be’ mandate of religious authority.

In conclusion we can say that the audience to performance relation in Artaudian theatre and IS media shows parallels on the subject of rhetoric. Although Islamic State media, unlike Artaud, are actively seeking their audience’s engagement, the trope of shock they employ is similar to Artaud’s. Furthermore, the hierarchical structure used in Artaudian theatre to assure dominance over the audience finds a parallel through the use of non-dialogical rhetoric in IS media. This becomes most evident in the citations of Islamic scripture used in their media outlets. Finally, a parallel can also be observed with regard to the anticipation of crowd behavior. While Artaud sought to ‘immobilize’ the individual intellect, Islamic State through its shocking messages, spreading like wildfire through social media, likewise triggers gut reactions that bypass the individual intellect.

4.3 The practical performance

In this section, we present an analysis of Although the Disbelievers Dislike it, and discuss whether the various elements can be said to correspond or not to those in the Artaudian theatre. The opening sequence of Although the Disbelievers Dislike It[lxi], shows a blue world map centering on Iraq and Syria. A bright light can be seen spreading across the globe: a metaphor for the political influence of Islamic State. It can be argued that the color of the world map – blue – is a metaphor for the divine, symbolizing the power of the idea of a world created by a deity with the intention for it to be an earthly paradise for its followers. The camera subsequently moves over Rome, China and the United States. Although the implication of this scene is twofold – a display of ambition and a call for action – the suggestion is that Islamic State will eventually spread across the entire planet. Next, the message of this animation is expressed in quoting the prophet Mohammed (Sahih of Muslim[lxii]): ‘Indeed, Allah Gathered the Earth for me, and thus I saw its eastern and western extents, and indeed the reign of my Umma will reach what was gathered for me from the Earth’. The male voice in the background of the clip sings a religious chant.

This segment with the narrative of the spreading of the Umma can be interpreted in terms of Artaudian theatre. Artaud, performing in the Jarry Theatre, created an atmosphere of ‘eeriness’, of mystery and the irréel, in order to have his audience experience a gap between the material world and a ‘frightening invisible one’. His décor consisted of objects ‘violently real’, signifying an immaterial world at work.[lxiii] In the video, the décor of a world map, conquered by a prophetic force, accompanied by Arabic chanting and religious text, is both fearful and reminiscent of higher forces at work, whilst still functioning as a depiction of the material world. The first segment thus acts as a mediating object ‑ a piece of scenery ‑ in between a material and an invisible world.

The second scene of Although the Disbelievers Dislike It[lxiv]starts with Islamic State’s most iconic piece of music containing the famous line Dawlat al-Islam Qaamat (‘The Islamic State has risen’). Winter[lxv] describes this scene as a ‘pseudo-documentary’ which (re)tells the historical frame within which Islamic State was founded. The scene is shown in a blue picture frame, reminiscent of Western news reports, suggesting both divinity and objective value. The blue frame in theatrical tradition is called the proscenium[lxvi], a tool for directing the audience’s attention towards an immersive experience. During this segment, the narrator gives a historical overview of the emergence of Islamic State in the past decade, -with arguably subjective elements added. Rhetorical elements can be discerned, such as the use (and repetition) of the term ‘crusaders’[lxvii], creating a religious context for the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the term ‘sons of Islam’, and a reference to Dabiq (see note 4), where they will eventually ‘strike the armies of the cross’[lxviii], suggestive of conviction and cause. This scene offers a sense of historical relevance, victimhood and a legitimization of the IS cause[lxix]. It also serves to underline the legitimacy of the leader of Islamic State, caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. At 04:06, an iconic image is used of an armed militant carrying the banner of IS, walking along local scenery somewhere in the Caliphate. The image, showing the militant in profile, bearded and dressed in black attire, portrays an idyllic version of the caliphate warrior. The scene, as was already observed above, is visually reminiscent of the famous picture of American soldiers raising the flag on the island of Iwo Jima during the Second World War. It should be noted that during this interlude the proscenium used in the first half of the scene has disappeared, as if to suggest a strong distinction between the past and the present, underlining the factuality of that which has passed, and emphasizing the reality of Islamic State having settled itself upon the world stage.

The scene continues with a speech by caliph al-Baghdadi[lxx]. He explains why one should not stay in a land where ‘Abu Bakr and Omar are insulted,’ (i.e. the lands where Shiites reign, see earlier above). This is either meant to refer to the start of the Caliphate in Syria, or as a justification for engaging in armed conflict, even against other ‘Muslims’. There is strong evidence to suggest that the latter is the case, as the scene following al-Baghdadi’s speech is one of heavy combat. The narrator continues to comment on the images, now shown[lxxi] without the use of a proscenium. Rather than being an attempt at describing history, the comment serves as an ominous threat: ‘It was not befitting for the grandsons of Abu Bakr and Omar [..] to take the stance of a subservient and humiliated person. So they sharpened every blade, to make the rafidah (‘the rejecters’ (of true Islam) as IS calls the Shiites) taste all sorts of killing and torment.’ Up until 07:34, the video shows battle scenes, more specifically victories won by Islamic State. This segment ends with the narrator forecasting war ‘until Allah is worshipped alone.’

The second scene has certain elements that fit the Artaudian tradition, along with some that contradict his ideas: The use of IS’s rhythmic, iconic hymn Dawlat al-Islam Qaamat produces an unsettling effect in an unfamiliar audience. The narrator then, in his depiction of Islamic State’s history, takes his audience along into an alternate reality. It can be argued that the use of a fixed text, a script written by an author, is not within the strict concept of the Artaudian director’s role. This element can therefore be said to be Artaudian in goal, but not Artaudian as an instrument in the play. The use of a proscenium in conjunction with a ‘frameless’ total experience in the latter half of the scene parallels Artaud’s use of both bourgeois theatre techniques for immersion and avant-gardist views[lxxii]. The introduction of caliph al-Baghdadi, particularly in view of his position as leader of Islamic State, constitutes a strongly religious directive force, akin to the Artaudian structure of hierarchy: ‘His director emerges as a ruthless holy man who commands the audience in the name of a “secret” goal, using the theatre as a means to a revelation that operates beyond the bounds of the theatre’[lxxiii]. Finally, in the theme of invasion, mentioned both in the reference to the war in Iraq and subsequently in the rise of Islamic State, there is an immediate parallel with the works of the Jarry Theatre, where Artaud would practice his early conceptions of theatrical revelation, a state of total understanding through the vision of ‘dark forces, invasion, and catastrophe’[lxxiv].

The third segment shows the execution of twenty-two Syrian army captives. This scene is arguably the most theatrical element of the entire video Although the Disbelievers Dislike It. Starting at 07.39, it shows the captives escorted by IS fighters against the backdrop of an olive grove. They are walking in double file, one soldier escorting one prisoner, the latter with their heads bowed down, as in submission to the sons of Islam. At 07:47, the camera angle changes, now showing the barefoot prisoners walking beside the soldiers. This shot emphasizes the relation of power between the prisoner and his escort, soon to be executioner. In front of the line, the infamous ‘Jihadi John’ walks in full black attire. He is dressed in the stereotypical outfit of militant Islamists[lxxv], whilst his fellow soldiers are wearing conventional military outfits. During frames 07:50-08:00, several different camera angles are used, either focusing on the surroundings of the olive grove, or on the faces of the young IS fighters. It should be noted that up until this point Jihadi John’s is the only face that is covered. At 08:02, the line of IS fighters walk past a crate filled with army-style combat knives. The action slows down dramatically while the executioners pick up their weapons; the inserted sound of sharpening knives adds intensity to the scene. The faces of the IS fighters, apart from ‘Jihadi John’s’, are fully visible. There is no sense of anonymity, nor does the gaze of the camera seem to be intruding on the soldiers’ privacy. They are fully aware of their role as actors and act accordingly. At 08.28, the group lines up at an open spot where the execution will commence. At 08.34, ‘Jihadi John’ begins to address president Obama, just as he did during his earlier appearance in the video A Message to America. This scene is carefully orchestrated, as we see a close-up of the line of prisoners and executioners, with ‘Jihadi John’ at the center flanked by two soldiers. At their feet, there are three prisoners, kneeled down obediently. ‘Jihadi John’ now utters religious-war rhetoric: ‘By Allah’s permission, we will break this final crusade.’[lxxvi] The scene with the three kneeled prisoners at the feet of their executioners reminds us of the holy trinity, underscoring through symbolism the narrative of an interreligious war. If you listen closely during this segment you notice that the original sound must have been dubbed over and the new recording inserted later in the audio track. If anything, this means that the message spoken by ‘Jihadi John’ was scripted in advance. At the 09:00 minute mark, there is a dramatic focus on the Nusayri prisoner at the feet of Jihadi John, followed by a close-up of an executioner warming up his hands and knife. For 45 seconds, there is a buildup of dramatic tension, with shots alternating between Nusayri soldiers, IS fighters, and knife play. There is little audible sound, while the tension builds, and extra attention is drawn to the images shown.

At 09:45, ‘Jihadi John’ gives his group the command to execute the prisoners. For ten seconds, we hear the sound of a heartbeat, heavy breathing, and camera shots alternating with a black screen. These are effective techniques to build up dramatic tension, culminating in the horrible act about to take place. From 09:55 to 10:24, the gruesome execution of the twenty-two captives is displayed. There are different camera shots, showing the desperation and the pain on the prisoners’ faces during the cutting of the throats and the subsequent decapitation, and a stream of blood, flowing on the ground.

After the execution has taken place, the atmosphere of the scene changes dramatically. It shows the calm hands of the executioners and their bloodstained knives at 10:27, with only the sound of gushing winds in the background. The camera pans to the corpses of the Syrian men, decapitated, with their heads on their chest facing the camera. At 10.38, the camera pans again, now focusing on the grim faces of the Islamic State soldiers, showing neither joy, nor resentment, only firm determination. The IS fighters appear to be men of different nationalities, which as Winter[lxxvii] remarks, is not a coincidence: ‘the novice executioners are deliberately given a central role, almost as if this footage featured a jihadist “homecoming”, made primarily to focus on IS’ most favored foreign fighters’ . This segment of the video is concluded with these final words: ‘Know that we have armies in Iraq and an army in Sham (= Syria) of hungry lions, whose drink is blood and play is carnage’.

This segment is considerably Artaudian, as it is not merely theatrical, but also staged as an event led by an authoritative figure, using a rhetoric akin to that of the words that rang through the Jarry Theatre. Looking more closely at the scene, starting at 07:39, we see the twenty-two prisoners walking in an orchard, heads bowed down next to their executioners. With the camera focusing on the Islamic State soldiers, we witness a duality of those who are about to die, and those who will go on living – the conquered and the conquerors. It is reminiscent of the Artaudian disposition of the actor and the inanimate representation of the figure often found in his theatre, signifying the mediating force between the visible world and the invisible world that Artaud sought to uncover. In the Artaudian theatre, there is a concentration of power centering on the director of the stage, which is remarkably similar to the position of ‘Jihadi John’ both during the progression through the orchard and during the execution itself. Upon passing the block of knives, time is alternately compressed and drawn out, the action slowing down and speeding up, thus capturing the audience’s attention in similar fashion as Artaud would do to immerse his audience in the play[lxxviii]. The execution itself, starting at 09:45, is obviously of vital importance in a comparison with the theatre of Cruelty. As critically as Artaud perceived cruelty as an instrument of the ‘dissolution’ of hierarchy[lxxix], so the use of cruelty itself became the hallmark of the Artaudian theatre. During the execution, the audience is no longer being addressed; there is no longer a call for action or engagement. The execution serves as a punishment[lxxx] rather than a provocation; the audience, whether enemy or potential ally, is in shock, and profoundly affected by what it has witnessed. It is a shock felt throughout the entire body, right down to the organs. The heads of the executed prisoners are placed on top of their mutilated bodies. A small stream of blood is visible at 11:18, accentuating the visceral currency in which Artaud would offer his revelation. The beginning of the fourth segment of the video[lxxxi] is much like the opening sequence of Although the Disbelievers Dislike It, but rather than presenting an articulated message, it consists primarily of the vocal pledges of jihadist groups swearing allegiance to Islamic State: ‘To the Khalifah Ibrahim Ibn ‘Awwad Ibn Ibrahim al-Qurashi al Husayni, pledging to selflessly hear and obey, in times of hardship and ease, and in times of delight and dislike. We pledge not to dispute the matter of those in authority’. We see the Islamic State flag flying over regions whose jihadist groups swear their allegiance to IS, local militants active in Yemen, Libya and Algeria[lxxxii]. The pledge of allegiance (bay’ah) is subsequently accepted in a second voice recording of al-Baghdadi, in which he announces the expansion of the Caliphate into these regions[lxxxiii].

It should be noted that the words used by the different jihadist groups mix and link up seamlessly, which shows that the ‘bay’ah’ comes in the form of a standard formula that has to be memorized. This obviously goes against the ideas of Artaud, as he abandoned the use of scripts in favor of production plans, thereby giving the actor the artistic freedom to represent the spirit of the text, rather than give a literal rendition of it. Although the appearance (in sound) of al-Baghdadi again underlines the ominous presence of a strong religious figure in the play, the content of this segment is rather practical in nature and does not show significant parallels worth mentioning.

The fifth and final segment[lxxxiv] shows ‘Jihadi John’ with the severed head of Peter Kassig, addressing President Obama and challenging him on his geopolitical policies concerning Iraq. This segment is stylistically very different from the preceding segments of the video and earlier videos featuring the executioner. As Winter remarks: ‘The fifth and final section […] is remarkably inconsistent with the rest of the video and, indeed, all previous IS executions of Western hostages.’ He points out a qualitative difference in production, making the segment seem ‘disjointed’ and ‘tacked on as an afterthought.’[lxxxv] According to Winter, the plausibility of the scene is a point of discussion[lxxxvi], as the footage appears to have been digitally edited. ‘Dabiq’, which features prominently earlier in the video, and is also mentioned by ‘Jihadi John’, appears in writing in the upper right-hand corner of the screen. This suggests that the scene was shot in Dabiq itself, and that the audience is being shown the landscape in which the prophesized battle at Dabiq will take place. ‘Jihadi John’ concludes his speech: ‘And here we are, burying the first American crusader in Dabiq. Eagerly waiting for the remainder of your armies to arrive.’[lxxxvii] The segment is concluded with a final statement by al-Baghdadi in Arabic, whilst the image of the IS soldier, carrying the Islamic State flag is repeated.

Unlike the previous parts of Although the Disbelievers Dislike It is, the final segment converges widely from the characteristics of Artaudian theatre. In contrast to the hierarchical structure of the previous, carefully orchestrated scenes, this scene is rather like a personal challenge or threat, with a dramatic change of tone in the words uttered by ‘Jihadi John.’[lxxxviii] We are past the moment of cruelty, the beheading of Peter Kassig, almost like it never happened. There are no more elements of immersion to be considered, and even ‘Jihadi John’, who only a moment ago led a progression toward a climax of theatrical tension, has dropped his prowess as an authoritative figure. Although this segment shows little resemblance to Artaudian theatre, it is not entirely surprising that it should have been added in the narrative of this video; it serves like a clergyman’s moralizing speech, reiterating the justification of the Jihadi cause after the theatrical climax in segment three.

The question we wanted to answer is whether or not the practical performance of Although the Disbelievers Dislike It compares to the Artaudian performance. Looking at the different segments, it is clear that the introductory segment does fit the Artaudian tradition. The second segment shows strong resemblances, even though the theme of invasion is itself presented as a revelation by IS, rather than being used as a catalyst for theatrical revelation. It can be argued that this notion is not outside of Artaudian tradition per se, as the actual catalyst for theatrical revelation is presented in segment three, thus also making the theme of invasion a separate constituting element of the Islamic State narrative. The third segment perfectly fits the Artaudian tradition, showing surprising parallels with the actual Theatre of Cruelty: the actors and their doubles, the biblical scenery of the orchard, an authoritative leader, and a cruel beheading scene that acts as a catalyst for theatrical revelation. The fourth segment shows no particular parallels with the Theatre of Cruelty, but it is clear also that it serves little dramatic purpose. It merely affirms the narrative of the expanding Caliphate. The fifth and final segment constitutes a stylistic break with the previous segments and shows little resemblance to the Theatre of Cruelty; it is like an epilog, justifying once again the arguments for the Jihadi cause. Concentrating on the first three segments, we can conclude that there are evident and strong parallels between the IS video and the Artaudian theatre. Although the final two segments are far less comparable to the Theatre of Cruelty, we argue that they serve a different purpose in the overall narrative, but as such do not contradict the argument that there are strong parallels between Although the Disbelievers Dislike It and Artaud’s visions.

Chapter 5. Conclusion

To formulate a thoroughly substantiated answer to the question if the hypothesis of this study – ‘The Islamic State’s media productions carry out Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty’ – can be corroborated, we have divided the research into three different domains to find matching and conflicting characteristics: the ideas, the audience and the performance in the two ‘theatrical’ manifestations. As such, we have come to the following conclusions.

Abu Bakr Naji proposes three ideas behind the use of Jihadist media: To lend strength to the justification of Jihadism through rational thought and sharia law, to overcome societal structures through the power of fear and violence, and to incorporate destabilized regions into the Umma. Similarly to Naji, Artaud proposes as main ideas behind the Theatre of Cruelty a search and longing for a divine source of authority, to obliterate the fetters of a ‘manmade’ culture through the use of shock and violence, and finally, to live in a truly natural state of being. Although the Umma is described as the Jihadist utopia, it is as much as an impossible absolute as Artaud’s strict visions for humanity’s true ideal life. Therefore we conclude that the ideas behind the Theatre of Cruelty and the Islamic State are indeed comparable.

The audience to performance relationship of Islamic State’s media outlets is characterized by a non-dialogical rhetoric, mandated by the use of Islamic scripture, which is full of cruel imagery, to shock and engage the audience. The Theatre of Cruelty devised similar principles of audience to performance relationships in order to bring about a punishing, cruel and liberating experience for its spectators. The perception of the audience as a crowd is a fundamental element of the Theatre of Cruelty, and shows a strong parallel with the Jihadist use of social media, spreading their ideas through an online community as if it were a crowd. It is legitimate to conclude therefore that the audience to performance relation in the Islamic State media and the Theatre of Cruelty is comparable.

The practical performance, as studied through the case of Although the Disbelievers Dislike It, shows strong similarities with practical elements in, and the actual performance of the Theatre of Cruelty.

Taking into account the results of each independent research question proposed in this study, observing significant parallels between the Theatre of Cruelty of Antonin Artaud and the cruel videos of Islamic State, and as stated above considering the fact that the message of cruelty is central to many of their videos, we conclude that ‘Islamic State’s media productions indeed implement the characteristics underlying Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.’

Hugh Prysor-Jones in Chronicles Magazine[lxxxix] stated that Islamic State has ‘read the book’ on Artaud, and describes Islamic State media productions as being inspired by Artaud’s ‘assault of the senses.’ We do not know if IS propagandists are aware of the existence of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty but it is evident that IS is implementing its characteristics. The question that remains to be answered now is: what does this mean? What does the connection between the two tell us? The Theatre of Cruelty presents a fictional happening to reach ultimately an impossible absolute, an eloquently conceived state of the human ideal being. It was never realized, because crossing the barrier of the fictional would imply that real violence and cruelty is necessary to achieve that which is idealized, and would therefore automatically be halted by authorities (one could even argue that such a dramatic revolt in the West could only and solely be executed in a – virtual– art or philosophical sphere). The Islamic State is not constrained by such limitations. A more important consideration is that Artaud never meant to actually use real violence and cruelty to reach his goals. Violence and cruelty were meant to be virtual procedural effects to reach the dreamed ideal. The cruelty used by the Islamic State is part of a ‘real time’ strategy to create its prophesized Umma. The Islamic State faces no significant internal opposition in the territory it controls, and as such, has the freedom to exercise its ‘Management by Cruelty’, resulting in, amongst other things, its violent and cruel media productions.

‘ISIS is systematically working to use visual standards that will give their videos an underlying professional look to someone whose eye is accustomed to a European or North American industry standard’ state Dauber & Robinson[xc]. Working this way Islamic State deliberately confronts the West with scenes of violence that are so similar to Hollywood action movies: fictional scenes of violence that ‘we’ enjoy for our pleasure, are now manifested into reality. In that sense, Islamic State is holding up a mirror for the West, as if saying: ‘This is your perverse image of heroism and sensational courage; and we are merely living your fantasy. See what hypocrites you are, condemning our cruelty, while enjoying your own fictional cruelty.’ We believe that it would be unwise not to take this message from Islamic State seriously. The mirror Islamic State is holding up to us does make us aware that we are indeed enjoying violence as a fiction – as a fantasy. It is part of our culture and it would make us indeed hypocrites if we condemn the Islamic State for only realizing what we already advocate and enjoy in our own works of fiction. It places us back on our feet, and we might ask ourselves if we should not reconsider the role of violence and cruelty in our Western body of fiction.

However, there is another essential point: Violence and cruelty in Western media are fictional, but have long been subject of discussion. Is violent imagery not detrimental to children? Can people be incited to crime after seeing cruel and violent films and playing similar games? These are legitimate questions indeed. But do we need Islamic State to confront ourselves with these questions? And what is the moral right of Islamic State to teach us this lesson? Should we listen to people who make a double caricature of our culture by turning torture and murder into a reality?

And there is still another point to be made: Cruelty and violence are indeed inevitable elements of human being’s nature. Denying these is pointless. Mankind has to do something with it, and from that perspective, it is much better to incorporate these darker sides of men in the metaphysical sphere where no real physical harm is done. We are deliberately speaking here of mankind, irrespective of religious or ethnic background, because there are Westerners and Easterners that have learnt this dear lesson: acknowledging the dark side of men and expressing it in art; this happens in Egypt, Morocco, Iraq and Syria as well.

The lesson Islamic State thus has to learn is much more pertinent: its fighters are actually killing in its ‘art productions’. Still, we cannot realistically expect that the Islamic State will be ready to learn the lesson of expressing one’s ideals metaphysically because it aims to realize its scenario, consciously or unconsciously based on the principles of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, into the physical realm. Looking at the fundamentals of both Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty and Islamic State’s cruel videos, they revel in similarities. Considering however the schism between the virtual and the real world, Artaud and Islamic State’s worlds could not differ more.

Notes:

[i] We owe thanks to our colleagues Pieter Nanninga of Groningen University, Herman Beck and Sander Bax of Tilburg University and Kimberly Jannarone of the University of California for their comments on an earlier version of this paper.

[ii] Prysor-Jones, 2014.

[iii] Sakurai, 2014.

[iv] Winter, 2014. 12.

[v] Butcher, 1902.

[vi] Grotowski, 2002. 255.

[vii] Naji, 2006; Saltman & Winter, 2014. 29; Hashim, 2014.

[viii] Naji, 2006.

[ix] Ibid. 51.

[x] Ibid. 51.

[xi] Ibid. 91.

[xii] Saltman & Winter, 2014. 38.

[xiii] Naji. 2006. 14-15.

[xiv] Ibid. 50-51.

[xv] Winter, 2015. 32.

[xvi] Saltman & Winter, 2014. 38.

[xvii] Winter, 2014.

[xviii] http://corpus.quran.com/translation.jsp?chapter=9&verse=32

[xix] Winter, 2014. 2.

[xx] Winter, 2014. 2.

[xxi] Ibid. 4.

[xxii] Ibid. 8.

[xxiii] Islamic State, 2014. 4:10.

[xxiv] Ibid. 4:17.

[xxv] Ibid. 10:38.

[xxvi] Jannarone, 2012. 1-2.

[xxvii] Artaud, 1938. 7. We used an English translation of his work. See references.

[xxviii] Jannarone, 2012. 42.

[xxix] Ibid. 50.

[xxx] Ibid. 33.

[xxxi] Ibid. 75-77.

[xxxii] Ibid. 85.

[xxxiii] Ibid. 86.

[xxxiv] Ibid. 86.

[xxxv] Ibid. 159.

[xxxvi] Ibid. 144.

[xxxvii] Ibid. 146.

[xxxviii] Naji. 2006.

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] Artaud, 1938. 7.

[xli] Naji. 2006. 184.

[xlii] Artaud, 1938. 2.

[xliii] Ibid. 126.

[xliv] Islamic State, 2014. 4:18.

[xlv] Artaud, 1938. 15.

[xlvi] Naji. 2006. 51-53.

[xlvii] Ibid. 67.

[xlviii] Jannarone, 2012. 1.

[xlix] Saltman & Winter, 2014. 31-32.

[l] Dabiq is a place in North-Western Syria where the Islamic Armageddon will ultimately take place. See all volumes of Dabiq on http://www.clarionproject.org/news/islamic-state-isis-isil-propaganda-magazine-dabiq

[li] Jannarone, 2012. 82.

[lii] Ibid. 85.

[liii] Ibid. 87.

[liv] Ibid. 87.

[lv] Ibid. 77.

[lvi] Ibid. 82.

[lvii] Winter, 2015. 43.

[lviii] Jannarone, 2012. 84.

[lix] Ibid. 86.

[lx] Abu Bakr (573-634) and Omar (583-644) are two of the four rightly guided caliphs and successors of the prophet Mohammed. Both are important figures in Sunni Islam.

[lxi] Islamic State, 2014. 0:00-0:50.

[lxii] Muslim (around 815-875) collected traditions of the prophet Mohammed. His work is called the Sahih.

[lxiii] Jannarone, 2012. 150.

[lxiv] Islamic State, 2014. 0:51-7:35.

[lxv] Winter, 2014. 4.

[lxvi] Jannarone, 2012. 90.

[lxvii] Islamic State, 2014. 0:57.

[lxviii] Ibid. 1:15-1:17.

[lxix] Winter, 2015. 29.

[lxx] Islamic State, 2014. 5:11.

[lxxi] Ibid. 5:16.

[lxxii] Jannarone, 2012. 122.

[lxxiii] Ibid. 151.

[lxxiv] Ibid. 151.

[lxxv] A picture of Al-Zarqawi, linked to several terrorist organizations. http://www.globalresearch.ca/who-is-abu-musab-al-zarqawi/201

[lxxvi] Islamic State, 2014. 8:46.

[lxxvii] Winter, 2015. 7.

[lxxviii] Jannarone, 2012. 146.

[lxxix] Ibid. 123.

[lxxx] Ibid. 87.

[lxxxi] Islamic State, 2014. 11:18.

[lxxxii] Ibid. 12:17.

[lxxxiii] Ibid. 12:35.

[lxxxiv] Ibid. 13:55.

[lxxxv] Winter, 2015. 25.

[lxxxvi] Ibid. 29.

[lxxxvii] Islamic State, 2014. 15:19.

[lxxxviii] Winter, 2014. 25.

[lxxxix] Prysor-Jones, 2014.

[xc] Dauber & Robinson, 2015.

Bibliography

Artaud, Antonin. Le Théâtre et son double, trans. by Mary Caroline Richards (New York: Grove Press, 1958). Paris: Gallimard, 1938.

Butcher, Samuel Henry. Aristotle, the Poetics of Aristotle edited with critical notes and a translation. London/New York: MacMillan and Co, 1902.

Barret, Richard. The Islamic State. New York: The Soufan Group, 2014. http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/TSG-The-Islamic-State-Nov14.pdf

Canetti, Elias. Masse und Macht. Hamburg: Claassen Verlag, 1960.

Dauber, Cori E. & Robinson, Mark. ISIS and the Hollywood Visual Style. Jihadology, July 7, 2015, http://jihadology.net/2015/07/06/guest-post-isis-and-the-hollywood-visual-style/

Derrida, Jacques. Artaud le Moma: Interjections d’appel. Paris: Galilée, 2002.

Grotowski, Jerzy. Towards a Poor Theatre. Edited by Eugenio Barba. New York: Routledge, 2002. 255.

Hashim, Ahmed. S. The Islamic State: From al-Qaeda Affiliate to Caliphate. Middle East Policy vol.21, no. 4(2014): 69–83. Doi: 10.1111/mepo.12096

Islamic State. Although The Disbelievers Dislike It. Syria, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.clarionproject.org/news/gruesome-islamic-state-video-announces-death-peter-kassig

Jannarone, Kimberly. Artaud and his Doubles. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2012.

Naji, Abu Bakr. Idaara al-tawahhush. Akhtar marhala satamurru bihaa al-‘umma/ The Management of Savagery. The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Umma Will pass. Translated by William McCants. Olin Institute for Strategic Studies at Harvard University, 2006.

Prysor-Jones, Hugh. Islamic State and the Theatre of Jihad. Chronicles Magazine, October 1, 2014.

Sakurai, Joji. New Theatre of Cruelty: Beheadings Demand Civilization’s Response. Yale Global, October 9, 2014.

Saltman, Erin Marie & Charlie Winter. Islamic State: The changing Face of Modern Jihadism. London: Quilliam Foundation, 2014.

Sontag, Susan. Approaching Artaud. The New Yorker, May 19, 1973, p.39.

Winter, Charlie . Detailed Analysis of Islamic State Propaganda Video: Although the Disbelievers Dislike It. London: Quilliam Foundation, 2014.

Winter, Charlie. The virtual ‘Caliphate’: Understanding Islamic State’s Propaganda Strategy. London: Quilliam Foundation, 2015.