Introduction

Introduction

The organisers of the Conference proposed that this paper[i] should reflect on future relations between the Vrije Universiteit (VU) and South Africa (SA), ‘with an eye for and knowledge of the traditions in which we stand and operate’.[ii] Amongst some others, I will address three aspects to uncover the importance of relations for the future South Africa-Vrije Universiteit involvement. As will be indicated, such relations are intimately linked to the traditions in which we stand, but they are also in need of redirection. For this, I will develop a few case studies, deliberately using relations between the Vrije Universiteit and South Africa as examples. This will inevitably bring relations with Afrikaners specifically into focus, but the lessons learnt should be applicable with regard to future relations with all South Africans and all institutions in South Africa in general. This is important because it is premised that the SAVUSA (South Africa-Vrije Universiteit-Strategic Alliances) programme interprets future relations with South Africa in the widest possible sense. The following aspects were accordingly selected for reflection:

Context

The first aspect relates to the context that is defined for the new initiative at the Vrije Universiteit, and is expressed by the last part (-SA) of the SAVUSA acronym, namely ‘Strategic Alliances’. Although this aspect was not included by the organisers in the title proposed for this paper, I will address it in the first section as it is of importance in evaluating past traditions, as well as for planning of future relations.

Traditions

The second aspect deals with the role of traditions. The key issue is whether traditions have any meaning, positive or negative, when consideration is given on the formation of strategic alliances. The long history of interactions between the Vrije Universiteit and South Africa, specifically with regard to the recent past, opens up ample opportunity to reflect on the role of traditions.

Relationships

The title implies that the Vrije Universiteit wishes to deepen its relationship with South Africa. Relationships are influenced by traditions, but encompass a broader dimension. The context mentioned above implies a thorough-going reconsideration of existing relations, with SAVUSA as the instrument. Once again, an understanding of relations in the context of strategic alliances will need to be reflected upon.

Context – Strategic alliances

The last two letters of the acronym ‘SAVUSA’ indicates that the founders of this programme have created a new context for their future relations with South Africa, namely that of strategic alliances. Strategic alliances are widely practised in the field of business management and industry. This category of practice is built on very close relationships, as indicated by a description in a recent scholarly book on strategic management (Thompson, Gamble and Strickland 2004: 130):

During the past decade, companies in all types of industries and in all parts of the world have elected to form strategic alliances and partnerships to complement their own strategic initiatives and strengthen their competitiveness in domestic and international markets. This is an about-face from times past, when the vast majority of companies were content to go it alone, confident that they already had or could independently develop whatever resources and know-how were needed to be successful in their markets. … Strategic alliances are cooperative agreements between firms that go beyond normal company-to-company dealings but fall short of merger or joint venture partnerships with formal ownership ties.

Strategic alliances are partnerships that often exist for a defined period during which partners contribute their skills and expertise to a co-operative project. An ultimate aim of these partnerships, is frequently to learn from one another with the intention of developing company-specific expertise to replace the partner, when the contractual agreement achieves its aim or reaches its termination date. Such relations are complex. On the one hand the outcome is increased competitiveness for each of the partners, but on the other hand an outcome is expertise gained from a partner who might become a competitor after termination of the alliance. Accordingly, some key issues have to be understood, each raising many important questions that are essential in learning the intentions of prospective partners before they engage in a strategic alliance (Pearce and Robinson 2005: 219).

In industry, core competencies are seminal in identifying partners for an alliance. New competitive expertise has to develop from these competencies. Some key issues are, therefore, to assess and value the partner’s knowledge, to determine knowledge accessibility and evaluate knowledge tacitness and ease of transfer. These objectives raise questions like ‘What are the strategic objectives in forming an alliance?’ ‘Which partner controls key managerial responsibilities?’ and ‘Do we understand what we are trying to learn and how we can use the knowledge?’ (Pearce and Robinson 2005: 219). These authors also indicate the importance of key issues and questions linked to relations, like ‘What is the level of trust between parent and alliance managers?’ ‘Are we realistic about our partner’s learning objectives?’ and ‘Is the alliance viewed as a threat or an asset by parent[iii] managers?’

Thompson and his colleague’s underline that many alliances are unstable, break apart and fail. The commitment of the partners to work together and their willingness to respond and adapt to changing internal and external conditions are prime requirements for stable alliances.

A successful alliance requires real in-the-trenches collaboration, not merely an arm’s-length exchange of ideas. Unless the partners place a high value on the skills, resources, and contributions each brings to the alliance and the cooperative arrangement results in valuable win-win outcomes, it is doomed (Thompson, Gamble and Strickland 2004: 130).

Do these industry and company experiences have any validity in considering the formation of strategic alliances within higher education? The rest of the paper will focus on this question. However, a point of departure is firstly to reflect on an emerging new context in higher education itself, triggered by new modes of knowledge production and transfer.

Higher education transformation

It is generally recognized that universities are among the most stable and change-resistant social institutions in the Western society, seeing that their roots go back to medieval times. Amongst leaders in higher education consensus exists that the core functions of higher education – to educate (knowledge transfer), to do research (knowledge production) and to provide in community service (outreach, emanating from the knowledge base) – must be preserved, reinforced and expanded. However, there is also general agreement that higher education relevance is, and will progressively be, defined by the changing requirements of the global era of the twenty first century. Universities are, for example, no longer the sole custodians of their core functions. In addressing this reality, some universities systematically transformed to a new mode, which is already well researched and well documented (Clark 1990; Gibbons, Limoges, Nowotney, Schwartzman, Scott and Trow 1994). In his lecture on Higher Education Relevance in the 21st Century, delivered at the UNESCO World Conference on Higher Education in Paris, 1998, Michael Gibbons, then Secretary General of the Association of Commonwealth Universities, opened his presentation with a bold statement, summarizing the transformation that occurred in higher education over the past two decades (Gibbons 1998: 1).

During the past twenty years, a new paradigm of the function of higher education in society has gradually emerged. Gone, it seems, is the high-mindedness of a von Humboldt or a Newman with its pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. In their places has been put a view of higher education in which universities are meant to serve society, primarily by supporting the economy and promoting the quality of life of its citizens. … The new paradigm is bringing in its train a new culture of accountability as is evident by the spread of managerialism and an ethos of value for money throughout higher education systems internationally.

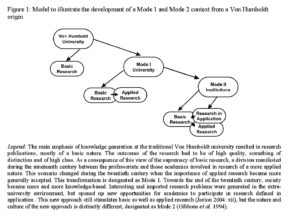

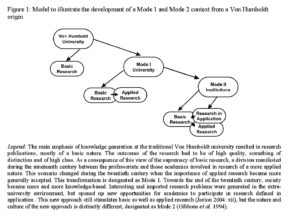

What Gibbons alluded to is the transformation in identity from the classic Humboldtian university of the nineteenth century towards emancipated contemporary institutions, forged by the transformation in their functions. According to Gibbons, research progressively underwent a change in context from curiosity-driven disciplinary knowledge (Humboldtian mode), through a phase where applied research complemented the traditional approach (called Mode 1), to the contemporary phase of knowledge production in application (designated as Mode 2). To illustration these transformations, I developed the model as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Model to illustrate the development of a Mode 1 and Mode 2 context from a Von Humboldt origin Legend: The main emphasis of knowledge generation at the traditional Von Humboldt university resulted in research publications, mostly of a basic nature. The outcomes of the research had to be of high quality, something of distinction and of high class. As a consequence of this view of the supremacy of basic research, a division manifested during the nineteenth century between the professoriate and those academics involved in research of a more applied nature. This scenario changed during the twentieth century when the importance of applied research became more generally accepted. This transformation is designated as Mode 1. Towards the end of the twentieth century, society became more and more knowledge-based. Interesting and imported research problems were generated in the extra-university environment, but opened up new opportunities for academics to participate in research defined in application . This new approach still stimulates basic as well as applied research (Jorion 2004: xii), but the nature and culture of the new approach is distinctly different, designated as Mode 2 (Gibbons et al. 1994)

A detailed analysis of the contemporary meaning of Mode 2 will not be presented here, as it is well covered elsewhere (Nowotney, Scott and Gibbons 2001). There are, however, several indicators which show where Mode 2 is flourishing.

Firstly, Mode 2 mostly implies a distinct degree of cross-institutional connectivity. When a knowledge problem requires participation of expertise from different types of institutions, the technique of ‘network management’ appears to be the method of choice. This implies a new management culture, as it differs from industrial production management directed predominantly towards profit, as well as the traditional academic management with its overt bureaucratic and collegial culture.

Secondly, Mode 2 is also reflected by the analyses of the ‘home bases’ of the academic outputs, like publications, books or patents. In a genuine Mode 2 research activity, for example, one would expect to find outputs that reflect not only multiple authorship, but also co-authors from different institutions – for example, from a public or private laboratory, a hospital or another university. Moreover, new scholarly journals have progressively been established during the past decade or two where research findings, emanating from Mode 2 knowledge production, are published.

Thirdly, Mode 2 can sometimes be identified by reviewing the types of financial supports or grants which an individual or group holds. More often than not, Mode 2 activity can be characterized by evidence of a concerted and systematic attempt to raise funding either from multiple sources or from funding agencies that have explicitly placed cross-disciplinary, cross-institutional or cross-national collaborations on their agendas. In South Africa, the THRIP programme[iv] of the National Research Foundation is a prime example of this.

How does this transformation of higher education relate to the aims of the SAVUSA programme? The present institutional view of the Vrije Universiteit will give direction to this question. In his address at the UNESCO Conference Gibbons (Gibbons 1998: 1) clearly indicates that universities that wish to accept the new paradigm will need adaptation and transformation. These changes might affect institutional goals, the university’s relations to the surrounding society and even its core values. It is therefore of interest to note that the organisers of the expert meeting described the Vrije Universiteit as ‘a truly Humboldtian university with clearly discernable emancipatory qualities’ in the first circular for the meeting. If the ‘Humboldtian’ culture is perceived to be dominant at the Vrije Universiteit, institutional goals are clearly directed towards traditional elitist academic ideals. These ideas are commendable, but do not hold very promising features for the formation of the kind of strategic alliances which might be of importance for future relations with South Africa. However, if the ‘discernable emancipatory qualities’ are also taken seriously, a future in the context of strategic alliances seems much more promising. Examples which will address these two alternatives will be addressed in the third part of this paper. However, it is essential that the meaning of traditions should firstly be addressed.

Traditions

Orientation

In strategic alliances, inter-institutional relations are of prime importance. Within the framework of this Symposium, the ‘meaning of traditions’ clearly relates to such relations. Traditions are therefore interpreted as the customs and practices that prevailed in the past, and which are handed down from generation to generation. The Christian character is the most prominent historical feature of the Vrije Universiteit, and also of South African traditions. Reflection on this will require a paper in its own right. The issue of our Christian traditions will therefore not be addressed here. In fact, it was also not explicitly included in the title which the organisers proposed for this paper.

Within the context of the SAVUSA programme, the traditions between the Vrije Universiteit and the former Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir Christelike Hoër Onderwys (hereinafter referred as the ‘Potchefstroom University’) are particularly illuminating. As an orientation on the meaning of traditions, it therefore offers an interesting case study. Our traditional interaction, of course, which took an about-turn in the 1970s, was well addressed by Dr. Harry Brinkman (Brinkman 2004) and therefore needs not be addressed again. Less attention was given to our traditions during the period since the renewed relations after 1990. It is timely, therefore, to elaborate on this aspect at this moment in time, as it is of significance where SAVUSA considers strengthening future ties with South Africa.

For this reflection, I therefore chose the date of departure as 21 May 1990. The occasion was an informal meeting between myself as Principal of the Potchefstroom University, Prof. Cees Datema, the Rector, and Dr. Harry Brinkman, the Chairman of the College van Bestuur[v] of the Vrije Universiteit. The meeting was granted at my request to meet with the management of the Vrije Universiteit. The venue chosen for our meeting was a small provincial restaurant in Woerden. I raised the only point on the agenda: ‘May we discuss the possibility to restore the broken relationship between the Vrije Universiteit and the Potchefstroom University’. The body language at the meeting was cordial but reserved. Although Pres. F.W. de Klerk had announced the abolition of institutionalized apartheid on 2 February 1990 and Mr. Nelson Mandela had already been released shortly thereafter, three months later students and staff from Potchefstroom, up to the level of the Principal, were still persona non grata at the Vrije Universiteit. We had to meet in Woerden. The meeting lasted for over two hours. Without going into the details of the discussion, it is sufficient to say that it was open, frank and direct. At the end, Brinkman’s conclusion was that they regarded Potchefstroom as a closed book, but from what was conveyed it seemed that a reopening of the VU-PU book might be a real possibility. Somewhat more than a year later, at the beginning of July 1991, Brinkman paid an official visit to Potchefstroom and substantiated the conclusions which he reached at Woerden the previous year.

The findings of Brinkman were made known at the Vrije Universiteit, and on 24 September 1991, I once again met with the College van Bestuur – this time at De Boelelaan. The afternoon I gave a public address in Afrikaans in the Aula at the Vrije Universiteit, officially announced as ‘Hoger Onderwijs voor het nieuwe Zuid-Afrika’.[vi]

Immediate speculations, especially by Ad Valvas,[vii] on the possibility of the formation of a new contract between the two universities were denied by both institutions, then as well as on later occasions. Regular contacts between the Vrije Universiteit and the Potchefstroom University did, however, progressively develop over the next few years. By 1996 it was proposed by Dr. Jan Donner, member of the College van Bestuur of the Vrije Universiteit, that a contract for co-operation should be formed between the two universities in view of their expanding co-operation.

Brinkman proposed a first draft for such an agreement, which was subsequently further developed by both institutions. On 21 April 1997 the Vrije Universiteit proposed a few final adjustments to the draft agreement, and the College van Bestuur informed the Potchefstroom University: ‘Met deze opmerkingen heeft het College van Bestuur overigens goedkeuring aan de formele totstandkoming van de samenwerking door middel van het sluiten van een overeenkomst gehecht’.[viii] Dr. Wim Noomen and myself signed the final document rather unceremonially on 15 December 1997 during an informal dinner in a restaurant in the Van Baerlestraat in Amsterdam, attended also by Dr. Jan Donner. It is unknown whether Ad Valvas was informed of this development.

This historical orientation may seem to be anecdotal, but the content of the contractual agreement, as well as its implementation, is significant in evaluating the meaning of traditions, especially with regard to future relations envisaged for SAVUSA. The first section of the agreement reads as follows:

Basis and purpose of co-operation

The agreement defines a relationship of co-operation between the VU and the PU vir CHO, with the following basis:

1. Recognition of the importance of an orientation towards the society within which each university functions;

2. Support of the development at both institutions in order to contribute to the continuous modernization of each of the institutions in response to the universal requirements of the age and the unique environment within which each functions;

3. Strengthening of both universities’ own responsibility for innovation and the continuity of their institutions;

4. Promotion of capacity-building and quality in the higher education sector in South Africa by means of various forms of institutional co-operation with other institutions in South Africa, where relevant and practicable;

5. In response to the Christian tradition of both institutions.

The contract laid a foundation for extensive deliberations and co-operation between the two universities on the managerial level, probably by far in the interest of Potchefstroom. Contributions by Dr. Harry Brinkman and Dr. Jan Donner at numerous strategic planning meetings of Potchefstroom sensitised the University to the importance of the society within which a university functions – nationally and internationally (Purpose 1). The financial management system, aspects of human resource management and the quality promotion system at Potchefstroom was directly developed by inputs from expertise proposed and defined by the management of the Vrije Universiteit (Purpose 2). Important academic innovations at Potchefstroom were creatively suggested and supported by the Vrije Universiteit (Purpose 3), as will be elaborated on in the last part of this paper. And fourthly, the constructive involvement of the Vrije Universiteit with various institutions in need of capacity-building (Purpose 4), for example at the University of the North West in Mafikeng, significantly contributed to the development, and in this case, to the success of the initial negotiations that eventually led to the merger which resulted in the formation of the new Northwest University.

The main conclusion to be drawn from this aspect of the case study, is that a formal agreement for co-operation between institutions is a key element to success, if taken seriously by those involved in the agreement. However, as a general guideline for future South African relations this is not enough. It should be reminded that the initiatives described above were taken in the first decade after the formal abolition of apartheid in 1990. Much has changed since then, and is progressively changing in South Africa. This also has to be taken into account in rethinking future relations between the Vrije Universiteit and South Africa. In view of its practicality, further reflections on the above mentioned case study will now be used to underline the importance of traditions in partnerships directed towards cooperation.

Emotive behaviour

In the distant past, relations of the Vrije Universiteit with South Africa mainly concerned Afrikaners and their institutions. Moreover, these relations initially had a strong emotional character, as the Dutch people generally regarded the Afrikaners as their Broedervolk.[ix] At the end of his well-known Evolutie-rede[x] of 20 October 1899, Dr. Abraham Kuyper even referred to the Afrikaners as ‘de helden van Transvaal, geen Calvinisten enkel in het woord, maar Calvinisten van karakter en vrome Calvinisten van de daad[xi] (Kuyper 1899: 55). Although some individual Afrikaners might have shared that emotional tie, we never had that passionate feeling for the stamland.[xii] The uniqueness of our common heritage was generally recognized among Afrikaners, in a somewhat subtle way. This was probably best expressed by Prof. J.D. du Toit in the metaphor ‘verborge-een’,[xiii] coming from his poem with that title (Totius 1977: 340).

The decline in this affectionate relationship, and the consequent broadening of the relations of the Vrije Universiteit with other South Africans and their institutions, was well covered at the SAVUSA Expert Meeting (Schutte 2004; Brinkman 2004). Nevertheless, the title proposed for this paper implies that traditions should act as a kind of pivot on which the door to the future might revolve. A key question, especially with regard to the context of strategic alliances, is whether the attitudinal traditions of the Vrije Universiteit towards Afrikaners will be of any meaning for their anticipated future relations with South Africa.

To address the ‘meaning of traditions’, I firstly refer to the occasion when Harry Brinkman received an honorary doctorate from the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education. In his address after the graduation ceremony, he gave in a nutshell a concise description of his experience over many decades of the broedervolk – and specifically of that of his brethren at Potchefstroom. He used the metaphor of a Januskop[xiv] as his concise description of the broedervolk. Given the dignity of the ceremony where he used this metaphor, as well as the fact that metaphors typically used by Brinkman are mostly well-founded, a reflection on the significance of the metaphor Januskop is needed. With regard to the aims of the SAVUSA programme, it may even illuminate obscured areas that might be of deep significance with regard to the future relations of the Vrije Universiteit with South Africa.

In Roman cult, Janus is the animistic spirit of doorways (ianuae) and archways (iani). His symbol is a double-faced head, which is the way he is seen represented in practice and in art. The Grote Nederlandse Larousse Encyclopedie designates a Janus as an ‘onoprecht, onbetrouwbaar persoon; huichelaar’[xv], and a Januskop as a ‘hoofd met twee aangezichten; huichelaar’ – definitely not the kind of character one would consider as a partner in strategic alliances. However, Brinkman did elaborate somewhat on the Janus metaphor in his ceremonial address. According to him, from the very beginning of his encounters with members of his broedervolk, he distinguished two broad categories of personalities: some more enlightened and others more fundamentalist, linking the Janus characterization to attitudes amongst Afrikaners to prevailing socio-political realities in South Africa during the second half of the twentieth century. This observation is also elaborated on in Verkennings in Oorgang, a supplementary edition of Koers, and compiling viewpoints expressed in 1994, 125 years after the founding of the Potchefstroom University (Coetzee 1998: 273). Had members of the broedervolk indeed been hypocrites and pretenders, the chirality of their profile would certainly not have been observable. Another interpretation of the Januskop seems, therefore, to be needed. One such an alternative is offered in Arthur Koestler’s elaborate account of the Janus phenomenon (Koestler 1979), although other interpretations of a Januskop exist, I preferred to use Koestler’s view to develop a working hypothesis for reflection on the meaning of traditions.

Koestler’s book is actually a summary of his work of over twenty-five years and it addresses the emotive behaviour in man and its society which played such havoc in the history of mankind. In his book, he designates the scale of entities, ranging from organisms, through man to society, as ‘holons’:

No man is an island; he is a ‘holon’. Like Janus, the two-faced Roman god, holons have a dual tendency to behave as quasi-independent wholes, asserting their individualities, but at the same time as integrated parts of larger wholes in the multi-levelled hierarchies of existence (Koestler 1979: i).

To develop his viewpoint of man and society, Koestler introduces a Janus principle as the basis of his thesis. The Janus principle is the assumption that each holon, (organism, man, society, etc.) is a self-regulating entity which manifests both the independent properties of wholes and the dependent properties of parts. In social hierarchies the Janus principle is evident: every social holon – individual, family, tribe or nation – is a coherent whole relative to its constituent parts. Yet, at the same time it is part of the larger social entity. ‘This implies that every holon is possessed of two opposite entities or potentials: an integrative tendency to function as part of the larger whole, and a self-assertive tendency to preserve its individual autonomy’ (Koestler 1979: 57).

According to Koestler, self-assertiveness manifests as ‘rugged individualism’, typical of the reformer, the artist, the thinker. Without their inputs in society, there can be no social or cultural progress. The integrative tendency is more complex. It manifests as subordination to a larger whole than that of the individual itself, and is therefore on a higher level in the social hierarchy. In a well-balanced society both tendencies play a constructive part in maintaining equilibrium. In this sense, the Januskop is an intrinsic constituent of every society. Order as well as progress in society is ensured by the self-regulation of these two properties. It should be noted that the societal equilibrium is not a static phenomenon, but dynamic in a progressive sense. Such a phenomenon is common in other fields as well, for example the well-described concept of a steady state or dynamic equilibrium observed in metabolism and enzymology in biochemistry, commonly known as Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

Koestler argues that derangement of balance in a holon, manifesting as a noticeably disturbed equilibrium. He names a few factors that may disturb the equilibrium. One factor is unqualified identification with a social group. Emotive identification with ‘the nation’ or ‘the political movement’ may easily become the driving force for overemphasis of the integrative tendency. By identifying themselves with the group, individuals may adopt a code of behaviour quite different from their personal code. According to Koestler, the Janus principle is intrinsic to all, and no society is prone to a disturbed equilibrium. Rather than mere hypocrisy, as interpreted by the Dutch encyclopaedia, Koestler’s interpretation of the Januskop, as ‘quasi-independent wholes’ appears to be a more fruitful model for understanding Brinkman’s observation of the broedervolk, and offers also a model to reflect on our traditions. To evaluate this model, the following working hypothesis is formulated: The Janus principle might be operative in both the Afrikaner and the Dutch societies, and would manifest during periods of complex societal conditions, like in the 1970s-1990s.

Even a superficial overview of the profile of the Afrikaners during the period 1970-1990 is sufficient to support the hypothesis that the Janus principle is operative in the Afrikaner society. The acerbity of Brinkman’s observation of the Afrikaners as a Januskop is probably most clearly expressed in a brief paragraph from the report on the 1976 discussions between the Vrije Universiteit and the Potchefstroom University vir Christelike Hoër Onderwys (Verslag 1976: 23):

De PU en haar docentencorps kan bepaald niet als een monoliet gezien worden. … Het is duidelik dat een aantal docenten van de PU in woord en geschrift de eigen bevolkingsgroep, de eigen achterban, trachten te overtuigen van de noodzaak van fundamentele veranderingen op korte termijn.[= ‘the self-assertive tendency’] Gezien de gespannen situatie opereren zij in een dikwijls moeilijk grensgebied van enerzijds nog aanvaarbaar zijn voor de eigen groep en anderzijds nog steeds niet aanvaarbaar zijn voor de niet-blanken. Voor ander docenten is de identificatie met de eigen groep primair [= the integrative tendency] en gaat deze uit boven de mogelijke identificatie met Christenen van een andere cultuur en/of ras.[xvi]

This report served as the catalyst to sever all ties between Potchefstroom and the Vrije Universiteit. It was followed by a period of progressive international censure against South Africa, to the extent that it became the polecat of the world. During the 1970s no Afrikaner in his right mind was unaware of the distortions of apartheid, although the vast majority remained supporters of the National Party. Nevertheless, the severity of the reaction of the Dutch against us was unexpected. In fact, the reaction from the 1970s to the early 1990s of the stamland towards the broedervolk was unparalleled by any other Western nation. It appears that at least two factors contributed to this severe reaction:

One generally accepted explanation is that the reaction was not against South Africa, but specifically against apartheid, the despicable form of institutionalized racial discrimination. Moreover, as this practice was instigated precisely by the broedervolk, fundamentally deepened the reaction of the stamland. This was commonly articulated as ‘sympathie over Zuid-Afrika en onbegrip t.a.v. apartheid’.[xvii]

A second factor was the emergence of a sincere commitment of the Dutch against any form of racial discrimination and the identification with those who sufferer under such discrimination. This is well illustrated in the recent obituary on the death of Rev. C.F. Beyers Naudé (1915-2004), drafted by a number of Dutch and related international societies (Obituary 2004). They acknowledged his unique role during the era of apartheid and referred to:

…zijn voorbeeld waaraan wij Nederlanders ons konden spiegelen en wij, pas laat, ons meer bewust werden van de eenzijdigheid van onze band met blank Zuid-Afrika en van de blinde vlek in het opmerken van de eeuwenlange onderdrukking van de zwarte bevolking.[xviii]

One has to agree that this Dutch response against Afrikaners was fully justified and fair. Nevertheless, in the case of the Afrikaners in South Africa, the progressive absolute political power of Afrikaner nationalists and their associated achterban[xix] became the dominant force within the broedervolk. Almost all critical voices from within – Koestler’s self-assertiveness – was stigmatised as verraad.[xx] The reaction against Rev. Beyers Naudé is a prime example of this. Koestler’s disturbed equilibrium amongst the Afrikaners eventually became the dominant profile of the broedervolk in the painful years of the 1970s–1980s. In fact, the Janus principle, required for the prevalence of a balanced society, became dysfunctional, rendering the Afrikaner society in a disturbed equilibrium, predominated by apartism.[xxi]

From this overview, it is clear that the Januskop-metaphor, as used by Brinkman, was much too narrow a characterization of Afrikaners. The Januskop was not just a case of an enlightened few opposed to a few fundamentalists. A disturbed equilibrium dominated within the Afrikanerdom. For Afrikaners, verification of the above-mentioned working hypothesis therefore seems to be possible.

For further verification of the working hypothesis, the attention should now shift to the Netherlands. The critical stance of the Dutch towards Afrikaners progressively intensified during the 1970s–1980s. Formal contacts and brotherly communication were replaced by severe professional and personal excommunication. Die Wende[xxii] in Europe, and the advent of a new South Africa, however, also triggered in the Netherlands some recapitulation on their relationship with South Africa – of which the SAVUSA Expert Meeting is also an example.

Derk-Jan Eppink, Editor of the in the NRC-Handelsblad, wrote an editorial in May 1990 (Eppink 1990) under the title Schuld en Boete,[xxiii] which is an illuminating example of the recapitulation on Dutch-South Africa relations at the beginning of the last decade of the twentieth century. The Editorial was a response to the visits of Pres. F.W. de Klerk to Europe. All countries welcomed him. Only the Netherlands refused to allow him in. Epping systematically analyses the anti-apartheid culture amongst the Dutch during the previous two decades. This culture eventually became inculcated within the Dutch as a form of penance for the guilt of the biased association with the Afrikaner broedervolk, with overtones of the role of the Dutch in the racial context of World War II. Epping reflects on the emotive eruptions against all that even remotely appeared South African: warehouses of Makro being burned down, benzene hoses of Shell being cut through and the books of the Afrikaans section of a library being thrown into the Amsterdam canals.

De banden moesten worden verbroken, het verleden ontkend. Nederland was vóór de derde Wereld, vóór ontspanning met het Oostblok: Nederland zag zich als gidsland. Maar Nederland was ook stamland van Zuid-Afrika, van Afrikaners en van dominee Verwoerd uit Amsterdam, grondlegger van apartheid. Dat kwam slecht uit. Als Nederland wilde doorgaan voor gidsland in de Wereld, dan moest het snel af van de predikaat ‘stamland van Zuid-Afrika’. … Het ‘thema’ Zuid-Afrika had in de jaren tachtig niets meer te maken met Zuid-Afrika zelf, maar alles met de Nederlandse binnenlandse politieke verhoudingen.[xxiv]

The key concept here is the tension between the Dutch ideals of stamland and gidsland.[xxv] Epping’s description of the gidsland of the 1970s-1990s closely relates to Koestler’s model where a new social holon emerges, governed by a new set of codes which define its corporate identity and its social profile. The advent of a new social holon, Epping’s ‘na-oorlogse protestgeneratie’,[xxvi] generated a new achterban. The new group created tension. But when tensions arise, the social holon tends to become over-stimulated. It imposes itself upon its rivals, or takes over the role of the whole. It is accompanied by an urge in society Reflecting the profile of the Dutch society of the 1970s-1980s, a disturbed equilibrium manifested in the Netherlands during the period of complex societal conditions of the 1970s-1990s. It seems justified to state that the Janus principle is not exclusive to Afrikaners, and supports the working hypothesis that the Janus principle is operative in both the Afrikaner and the Dutch societies.

Reconciliation

Although, as already mentioned, there was a growing discontent amongst Afrikaners concerning apartheid, and the realization that a fundamental change had to come, the impact of 2 February 1990 on South Africa, our own Wende, triggered a deep sense of introspection within ourselves. In fact, the speech of Pres. F.W. de Klerk is a prime example of the outcome of such an introspection (De Klerk 1990: 1):

The aim is a totally new and just constitutional dispensation in which every inhabitant will enjoy equal rights, treatment and opportunity in every sphere of endeavour – constitutional, social, economic. … This is where we stand: deeply under the impression of our responsibility. Humble in the face of the tremendous challenges ahead. Determined to move forward in faith and with conviction. I pray that the Almighty Lord will guide and sustain us on our course through uncharted waters.

The South African culture of racial discrimination transformed to a culture of reconciliation, often referred to as a miracle. It became visible through a wide variety of public manifestations. There was reconciliation between Rev. Beyers Naudé and his congregation in Johannesburg. By the promulgation of an act by Parliament, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established with the objective that the Commission had to promote national reconciliation in a spirit of understanding which transcended conflicts and divisions. The Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir Christelike Hoër Onderwys did not officially make a presentation at the hearings of the TRC. However, on its campus a process of reflection on the participation of the University in apartheid unfolded (Reinecke 1998: 181). It resulted in official declarations by the Senate and Council of the University. The declaration by the Senate of 4 May 1994 contained a confirmation of injustices and discrimination practised by the University against its fellow South Africans, culminating in a confession of guilt and deep remorse. The declaration by the Council of the University on 23 June 1994 endorsed the declaration of the Senate and added a commitment of the University towards the new South Africa:

– that the University enters the new political era in a spirit of commitment and enthusiasm and as a Christian University wishes to be involved in the community within which it functions in such a way that it fulfils its calling, although deeply aware of the complexities and challenges of the new era. It is the intention of the University as an educational institution to serve the country and its people in accordance with the requirements of this era;

– that for co-operation with the government, as with any other articulations of the community, constructive involvement is the point of departure of the University, but it should also guard against ever in this process becoming being uncritically subservient;

– that the Christian foundation of the University, as expressed in the motto ‘In Thy Light’ will continue to serve as a conscience, and as an inspiration to take seriously the ideals of the University, while above all recognizing the dependence on God Almighty for the fulfilment of the task of the University.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Broedervolk became the victim of British Imperialism, leaving a deep scar in the fabric of the Afrikaner nation, as expressed by Totius in one of his poems (Totius 1977: 22). Self-reflection at the end of the 20th century brought Afrikaners to the revelation of another scar: this time the self-inflicted scar in their fabric due to their ideological commitment to apartism.

What meaning can we now derive from our traditions as they functioned during the complex societal period in the second half of the twentieth century? The self-inflicted scar of apartism will be an indisputable part of the identity of Afrikaners, now and in the future. Afrikaners will have to make peace with this identity and learn to live with this reality in ages to come. In the case of the Dutch, an apparent emancipated attitude developed from their sincere attempts during the 1970s-1990s to eradicate their historical bond with Afrikaners. However, ever since Jan van Riebeeck set foot in the Cape, it is a profound historical reality that the Dutch are the stamland of the broedervolk. This historic reality is an indisputable part of the identity of the Dutch. It will always surface from time to time when Dutch–South African relations come under the spotlight, and they will have to make peace with it, and learn to live with this reality. This is of importance for our mutual future relations, but also in our relations with other South Africans and other South African institutions. The mere fact that the SAVUSA Expert Meeting devoted considerable time to reflecting on the history of the Netherlands and the Vrije Universiteit in South Africa presents an opportunity to address ways and means to handle our historical realities in a spirit of conciliation. If we succeed, the future of the SAVUSA ideal will be promising.

Relationships

The fruits of reconciliation

The date of 27 April 1994 marks the beginning of the new South Africa. By the first truly democratic election the Afrikaners practically terminated their superior political position in South Africa and symbolically and in reality handed over the future to the majority of South African citizens. It was not the outcome of a fatalistic mindset, but rather the result of a well-founded realisation in the minds and indeed the hearts of Afrikaners. However, it was President Nelson Mandela who, with dignity and confidence, became a national symbol of reconciliation for the building of a new nation, ripped apart by apartism. His inaugural address as the first president of the new South Africa is a prime example of his visionary expectations for the future (Mandela 1994: 1):

I have no hesitation in saying that each of us is as intimately attached to the soil of this beautiful country as the famous jacaranda trees[xxvii] in Pretoria and the mimosa trees [xxviii]of the bushveld. … We enter into a covenant that we shall build a society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in our hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity – a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.

Many Afrikaners found the new dispensation difficult. Some left for some new global destination. Many more stayed in South Africa and progressively became new South Africans. Shortly after his inauguration, President Mandela referred to this general spirit of commitment in his Presidential Address in the National Assembly (Mandela 1994: 271):

… as we sat here over these last days listening to the debate in this, our first democratically elected and fully representative Parliament, one could not help again and again coming deeply under the impression of the remarkable transition our country has experience – a transition from being one of the most deeply divided societies in the world to one so inspiringly united around the commitment to a common future. …

There were indeed some really moving moments in this debate as speakers responded to the exciting, inspirational and liberating possibilities and realities of our newly founded South Africanism. We heard some of our Afrikaner compatriots in this House hailing the dawn of the new democratic South Africa as an event of liberation for themselves rather than as an experience of loss, we heard the honourable leader of the FF[xxix]publicly acknowledging and paying tribute to the demonstrated desire of the majority party to create an inclusive nation in which there is a place for all.

These were some of the moments which captured the new spirit abroad in our country. Those responses demonstrated an encouraging generosity of spirit, reciprocating the generosity so abundantly displayed by the oppressed and suffering people who had mandated their leaders and representatives to negotiate politically a future of peace and forgiveness and inclusivity.

This transition is evident in many fields. A comparison of the poems of Heilna du Plooy in her first (Du Plooy 1993) and in her second (Du Plooy 2003) volumes of poetry, can serve as such an example. Dutch visitors to South Africa noticed the change and wrote on it in the Dutch press (Ester 2004) The association of the Afrikaners with the new South Africa, and an increased dissociation from their origins, became conspicuous. Nevertheless, Ester argues that Afrikaners still remain important partners in the considering of South Africa-Dutch relations.

The new higher education policy, promulgated in 1997, urged the higher education institutions to cultivate institutional cultures of respect and tolerance. Moreover, it was also expected that the institutions should increase a broader responsiveness to societal interests and needs. It required institutions to deliver the requisite research, highly trained graduates and knowledge to address the needs of an increasingly technologically oriented economy. These things had to equip South Africa with expertise to respond to national needs as well as to participate in a rapidly changing and highly competitive global context. The new socio-political national dispensation, as well as new policy developments, confronted the higher education institutions with local and global environments, never encountered by them before. The different ways in which the institutions responded or adapted to the new environment became well researched and documented (Cloete, Fehnel, Maassen, Moja, Perold and Gibbon 2002). It appeared that higher education transformation did not neatly follow the centrally planned policy route. The organisational responses to reform indicate three broad tendencies within the higher education sector (Cloete and Maassen 2002: 447).

The tendency among the historically white Afrikaans-medium universities was to embark on a variety of enterprising strategies. They were ‘remarkably successful in increasing their student numbers, enlarging their product range, securing research and consultancy money and introducing strict cost cutting measures’. This ensured that these universities were doing at least as well as before. It appeared that they were ‘undoubtedly the most responsive to the transformation initiatives of the new government. … It could be said that they “expanded” their domain’. These observations indicate that, superimposed on the national needs for transformation, the historically white Afrikaans-medium universities in general progressively incorporated various aspects of mode 2 characteristics in their institutional missions and culture.

‘The historically white English-medium universities vigorously participated in policy development processes’. Traditionally they had strong international ties, which they were able to maintain even during the period of the academic boycotts. Within the new environment they systematically changed ‘the complexion of their student body and leadership’, but bolstered their academic excellence by relying on ‘their traditional academic staff, dominated by well-qualified white males’. Although they apparently made compromises within the framework of new policies, they largely continued to do what they did before. ‘They thus ‘consolidated’ rather than expanded their domain, implying that they were more inwardly oriented than their Afrikaans-medium counterparts’.

Within the new environment they systematically changed ‘the complexion of their student body and leadership’, but bolstered their academic excellence by relying on ‘their traditional academic staff, dominated by well-qualified white males’. Although they apparently made compromises within the framework of new policies, they largely continued to do what they did before. ‘They thus ‘consolidated’ rather than expanded their domain, implying that they were more inwardly oriented than their Afrikaans-medium counterparts’.

The third tendency was that the transition to the new South Africa precipitated severe crises amongst the historically black universities due to a set of complex factors. The ‘interaction between historical disadvantage, geographical location, and accentuated inequalities driven by academic and management weakness in a competitive market environment’ virtually paralysed some of these institutions. They furthermore became disillusioned by the unresponsiveness of the new government in providing them with widely advocated redress funds. Many could not respond to the threats of the new environment and had virtually no resources to avoid crises.

The National Plan for Higher Education aimed to address the crises in some parts of the sector, but was also an overt ideological initiative to eradicate the ‘geo-political imagination of the apartheid planners’ and the realignment of the institutional landscape according to the ‘imperatives of the new democratic order’ (Asmal 2001). The National Plan provided a framework and mechanisms for restructuring of the higher education system. Central planning, regulation and control became dominant imperatives, diminishing traditional virtues of academic freedom and autonomy, and counteracting institutional transformation associated with the Mode 2 culture.

Ten years after the advent of the new democratic dispensation in South Africa, the South African scene indeed underwent fundamental changes. The fruits of reconciliation are a commitment to !KE E: /XARRA //KE,[xxx] the new formulation of the traditional South African quest for unity in diversity. One-party political domination, however, also spurs on policy initiatives that once again trigger new challenges for what are again new directions in uncharted waters. In such a scenario, partnerships of expertise and relations based on commitment progressively become desperately needed in South Africa. From the intentions of the custodians of the SAVUSA initiative, it does seem that this initiative is timely and well suited to address the need for partnerships in South Africa.

Partnerships

As indicated above, the formal agreement between the Vrije Universiteit and the Potchefstroom University fostered a culture of close collaboration on the managerial level between these universities. Item 3 of the PU-VU contract emphasized that innovation is primarily a university’s own responsibility, but a responsibility that can be mutually strengthened by co-operation. Mode 2 is one approach for innovation that might contribute to the continuity and long-term viability of the primary functions of a university. The formation of a Centre for Business Mathematics and Informatics (BMI) at Potchefstroom serves as a further case study to illustrate this point.

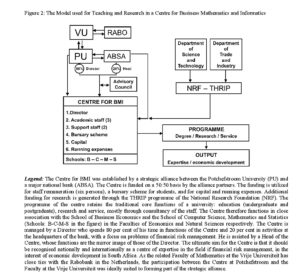

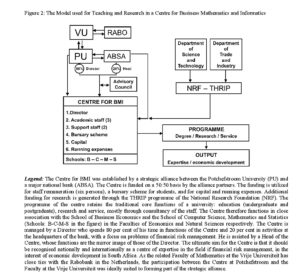

The Centre was a unique model for innovation at the Potchefstroom University, and its implementation was based on a suggestion from Dr. Jan Donner during one of the formal meetings on the managerial level. It was a proposal to foster innovation in the field of mathematics. Moreover, the initial participation of the Vrije Universiteit was seminal in the implementation of the innovation. This model is shown schematically in Figure 2. The Centre for Business Mathematics and Informatics was established in 1998 at the Potchefstroom University. After seven years, it is a shining example of a unique innovation that rendered the University the undisputed leader in the field of risk management in South Africa. Moreover, it is a prime example of a successful strategic alliance between the University and the private sector, through ABSA Bank.

Figure 2 – The Model used for Teaching and Research in a Centre for Business Mathematics and Informatics

Legend: The Centre for BMI was established by a strategic alliance between the Potchefstroom University (PU) and a major national bank (ABSA). The Centre is funded on a 50:50 basis by the alliance partners. The funding is utilized for staff remuneration (six persons), a bursary scheme for students, and for capital and running expenses. Additional funding for research is generated through the THRIP programme of the National Research Foundation (NRF). The programme of the centre retains the traditional core functions of a university: education (undergraduate and postgraduate), research and service, mostly through consultancy of the staff. The Centre therefore functions in close association with the School of Business Economics and the School of Computer Science, Mathematics and Statistics (Schools: B-C-M-S in the figure) in the Faculties of Economics and Natural Sciences respectively. The Centre is managed by a Director who spends 80 per cent of his time in functions of the Centre and 20 per cent in activities at the headquarters of the bank, with a focus on problems of financial risk management. He is assisted by a Head of the Centre, whose functions are the mirror image of those of the Director. The ultimate aim for the Centre is that it should be recognised nationally and internationally as a centre of expertise in the field if financial risk management, in the interest of economic development in South Africa. As the related Faculty of Mathematics at the Vrije Universiteit has close ties with the Rabobank in the Netherlands, the participation between the Centre at Potchefstroom and the Faculty at the Vrije Universiteit was ideally suited to forming part of the strategic alliance

The success of the Centre is reflected in a more than six fold increase in student numbers, 25 per cent of which are at an advanced level. All South African banks and financial institutions, as well as banks and financial institutions internationally, employ graduates of the Centre. Research in financial risk management within the Centre has been on the increase and is included in a recent book, compiled from twenty one seminal research published in The Journal of Risk. The remarks by Philippe Jorion, Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of Risk, (Jorion 2004: xxi) clearly indicates that the new field of risk management is a prime example of a Mode 2 enterprise:

The field of risk management … has developed an expanding body of knowledge in qualitative methods to measure the financial risks of complex portfolios. The ability to provide a comprehensive measure of financial risk has truly transformed the industry. … On the academic side, these developments have spurred fundamental research that complements industry research. In response to the demand for knowledgeable graduates in this field, leading-edge universities are now offering specialized courses in risk management.

There can be no doubt that within the Mode 2 context, there exists real possibilities, and a real need, among some sections of South African universities to form strategic alliances with relevant sections of Dutch universities. The Vrije Universiteit is well equipped for this role. The high quality of its research endeavours is reflected by its Von Humboldt identity and its openness to co-operation, through reference to its emancipatory character. The SAVUSA programme may be the ideal vehicle to stimulate such initiatives. A word of caution is necessary, however. Again, the Centre for BMI may be used to illustrate this point. The presence of the Vrije Universiteit in the Centre has diminished and has been replaced by co-operation with the Technical University (ETH) at Zurich in Switzerland. The Rabobank as a matter of fact was never really involved in the Centre, but a real strategic alliance on aspects of the activities at the Centre was formed after the establishment of the Centre with SAS, the international computer software firm. Consideration of the characteristics required for successful strategic alliances (Pearce and Robinson 2005: 219) can assist in understanding these developments at the Centre.

A new beginning

It will be for SAVUSA to design their strategy for their new initiative in South Africa. The commitments of the custodians of the programme indicate a will for success. In conclusion, three aspects are suggested to be on the agenda in planning the activities for the SAVUSA programme.

Equal partners

The time has come for co-operation between the Netherlands and South Africa to be one of equal partners. For the South Africans that will be quite a challenge. The demands of functioning as academics in a country with tremendous societal and developmental challenges are formidable. In at least the traditional Afrikaans universities, the backlog of a generation of suffering under an academic boycott are still very real, something which often still makes them academically weak partners. Given their short history as academic institutions, as well as the complexities discussed above, makes this an even greater reality at the historically black universities. For the Dutch, equal partners will mean resistance to any attempt of overemphasizing the gidsland attitude, with an open mind which reflects their commitment to equal partnerships, as Hans Ester (Ester 2004) clearly articulated:

De beste reactie uit Nederland is belangstelling, begrip en een weloverwogen weerwoord … Wij zijn terug bij het begin … De Nederlanders worden in een gesprek betrokken dat hen dwingt om ook over zichzelf na te denken en het eigen Europese licht niet onder de korenmaat te zetten. Dat is een eerlijke basis voor de verbondenheid van Nederland en Zuid-Afrika.

An alliance approache

Their context of a strategic alliance should be taken very seriously by SAVUSA. The three key issues here are (1) a focus on the quality of the inputs to come from those who participate in an alliance. This will require the need to focus, and to make clear, and often difficult, choices. (2) Complementarities of the expertise of the participants in a strategic alliance will simultaneously strengthen the individual and the collective expertise and competitiveness in their own academic and societal environments. (3) A commitment to the range of success factors that define strategic alliances (Pearce and Robinson 2005: 219). Innovation and long-term viability will be the ultimate benefits emanating from this approach.

The meaning of traditions

One final encounter with Janus, but now in its most ancient form, provides an inspirational conclusion to the reflection on the meaning of traditions. Janus is probably the oldest of the Roman gods. It was the god of new beginnings. Its normal place was at an entrance or at a doorway. Its one face looked to the past, so as to ensure that the lessons learnt and wisdom gained should not be forgotten, and that traditions cultivated should be cherished. The other face was directed to the future. It symbolizes an attitude of accepting the challenges that lie ahead and of fostering a sense of commitment and perseverance to ensure success. In times of peace and in times of battle Janus changed positions. Sometimes it was visible at the doorway, sometimes it was elsewhere. This means that traditions requires periodic reflection on their meaning, and should never deteriorate into an attitude that we have reached our final destiny. Every year begins once again with January; or, like the seasons, new beginnings always brings a new vitality as one of the Dutch poets (Gorter 1921) so eloquently said:

Een nieuwe lente en een nieuw geluid: …

Naar buiten: … Hoort, er gaat een nieuw geluid … [xxxi]

NOTES

i. The title for this paper as proposed by the organisers of the SAVUSA Expert Meeting.

From the letter of invitation from Prof. Dr. Gerrit Schutte as a guideline for the preparation of this paper.

ii. The title for this paper as proposed by the organisers of the SAVUSA Expert Meeting. From the letter of invitation from Prof. Dr. Gerrit Schutte as a guideline for the preparation of this paper.

iii. In the initiative for the development of A new ‘lexicography’ by experts from the University of Stellenbosch and the Vrije Universiteit, the universities are regarded as the ‘parent’ institutions and the experts as the alliance partners. A functionary to oversee the alliance would be referred to as the ‘alliance manager’, in this particular instance having been Dr. Harry Brinkman.

iv. The Technology and Human Resources for Industry Programme (THRIP) of the National Research Foundation, which resides under the Depertment of Science and Technology, is a partnership programme funded by the South African Department of Trade and Industry, managed by the National Research Foundation. It is guided by a board comprising representatives from industry, government, higher education, labour and science councils. Its mission is to improve the competitiveness of South African industry by supporting research and technology development activities and enhancing the quality and quantity of appropriately skilled people. THRIP also encourages and supports the development and mobility of research staff and students among participating organisations.

v. Management Committee.

vi. Higher Education for the new South Africa.

vii. In-house news journal of the Vrije Universiteit.

viii. With these comments the Management Committee approved the formal establishment of co-operation by concluding a contract.

ix. A nation of brotherhood.

x. Lecture on evolution.

xi. The heroes of the Transvaal, not merely Calvinists in their words, but Calvinists of character, and devoted Calvinists in their deeds.

xii. Country of origin and heritage.

xiii. Mysteriously related.

xiv. Head of Janus, the Roman god.

xv. Janus or a Januskop thus personifies a two-faced and unreliable person (= onbetrouwbaar persoon) and a hypocrite (= huichelaar). A hypocrite is also described as a pretender, a person guilty of hypocrisy. Hypocrisy, in its turn, is a simulation of virtue; a pretended goodness.

xvi. The PU and her lecturer corps should not be seen as monolithic. It is clear that a number of lecturers of the PU through discussion and writing try to convince their own cultural group, their own brotherhood, of the need for fundamental changes in the short run. Given the tense situation they often operate in a complex border area of still being acceptable to their own group, yet simultaneously not being acceptable to non-whites. For other lecturers the identification with the own group is of primary importance and supersedes any possible identification with Christians of another culture and/or race.

xvii. Sympathy regarding South Africa but incomprehension of apartheid.

xviii. His example on which we as Dutch people could reflect and from which we, quite late, became aware of our biased bondage towards white South Africa and the blind spot in seeing the oppression of the black community over centuries.

xix. Brotherhood.

xx. Betrayal.

xxi. The ideological manifestation of bondage to the apartheid paradigm.

xxii. The turn-of-the-tide.

xxiii. Guilt and penance.

xxiv. The ties had to be broken, the past denied. The Netherlands was in favour of the Third World, in favour of relaxation towards the Eastern Block. The Netherlands saw itself as a guiding nation. However, The Netherlands was also the country from which South Africa originated, of the Afrikaners and of Rev. Verwoerd from Amsterdam, founder of apartheid. That was bad. If the Netherlands wanted to be the guiding nation in the world, it had to quickly abandon the identity as ‘country of origin of South Africa’. … By the 1980s the ‘theme’ South Africa no longer concerned South Africa itself, but rather concerned internal political relations within the Netherlands.

xxv. Guiding country.

xxvi. Post-World War II protest generation.

xxvii. Exotic tree of South American origin.

xxviii. Indigenous South African acacia trees.

xxix. FF: Freedom Front, a white opposition party.

xxx. The Koi-San version of the South African motto on the national coat of arms.

xxxi. ‘A new spring and a new sound: … Let’s go outside: … Listen, a new sound is heard …’

References

Brinkman, H. (2005) ‘VU-South Africa, 1972-present: political and managerial developments’, in G.J. Schutte and H. Wels (Eds), The Vrije Universiteit and South Africa, from 1880 to the present and towards the future: Images, practice and policies, SAVUSA POEM Proceedings, Amsterdam: Rozenberg.

Clark, B.R. (1998) Creating entrepreneurial universities: Organisational pathways of transformation, Great Britain: Pergamon.

Cloete, N., Fehnel, R., Maassen, P, Moja, T., Perold, H. and Gibbon, T. (Eds) (2002) Transformation in higher education – global pressures and local realities in South Africa, Landsdowne: Juta.

Cloete N., and Maassen, P. (2002) ‘The limits of policy’, in N. Cloete et al. (Eds), Transformation in higher education – global pressures and local realities in South Africa, Landsdowne: Juta.

Coetzee, C.J. (1998) ‘Die PU vir CHO en die rasse- en volkereproblematiek’, Koers, Supplement 1, Potchefstroom: Buro vir Wetenskaplike Tydskrifte.

De Klerk, F.W. (1990) Opening of Parliament, Debates of Parliament (Hansard) of the second session of the ninth Parliament, 2 February.

Du Plooy, H. (1993) ‘Wintervloek psalm’, in H. du Plooy, Die donker is nooit leeg nie, Kaapstad: Tafelberg.

Du Plooy, H. (2003) ‘Landeskunde’, in H. du Plooy, In die landskap ingelyf, Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis.

Eppink,. D.-J. (1990) ‘Schuld en Boete’, NRC Handelsblad, May.

Ester, H. (2004) ‘Band met Zuid-Afrika is dun geworden’, Nederlands Dagblad, 10 August.

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotney, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P. and Trow, M. (1994) The new production of knowledge: Science and research in contemporary societies, London: Sage.

Gorter, H. (1921) Mei (6th edition), Amsterdam: W. Versluys.

Jorion, P. (2004) Innovations in risk management, London: Risk Books.

Koestler, A. (1979) Janus: A summing up, London: Hutchinson.

Kuyper, A. (1899) Evolutie, Amsterdam: Höveker and Wormser.

Mandela, N.R. (1994) Statement of the President of the African National Congress Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela at his inauguration as President of the Democratic Republic of South Africa, Union Buildings, Pretoria, 10 May 1994, Pretoria: CTP Book Printers.

Mandela, N.R. (1994) Presidential Address, Debates of the National Assembly (Hansard) of the first session of the first Parliament, 27 May 1994, Cape Town: Rustica Press.

Nowotny, H., Scott, P. and Gibbons, M. (2001) Re-thinking science, Malden (USA): Blackwell.

NRC Handelsblad (2004), ‘Overlijdensbericht – Dr. C.F. Beyers Naudé’, 16 September.

Pearce II, J.A. and Robinson, R.B. Jr. (2005) Formulation, implementation, and control of competitive strategy, New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Reinecke, C.J. (1998) ‘Die wording van die PU vir CHO as deel van die Suid-Afrikaanse universiteitsisteem’, Koers, Supplement 1, Potchefstroom: Buro vir Wetenskaplike Tydskrifte.

Schutte, G.J. (2005) ‘The VU and South Africa, 1880-1972: 125 years of sentiments and good faith’, in G.J. Schutte and H. Wels (Eds), The Vrije Universiteit and South Africa, from 1880 to the present and towards the future: Images, practice and policies, SAVUSA POEM Proceedings, Amsterdam: Rozenberg.

Totius (1977) Versamelde werke 10, Kaapstad: Tafelberg.

Thompson, A.A., Gamble, J.E. and Strickland III, A.J. (2004) Strategy – Winning the marketplace, New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Verslag van een samenspreking tussen delegaties van die Vrije Universiteit en de Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir Christelike Hoër Onderwijs (1976), Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

Introduction

Introduction