Abstract

Abstract

The aim of this study is to examine determinants of condom use intention of Tanzanian and Zambian high-school students. Additionally, we aim to investigate whether determinants differ among different target (sub)groups. Data were gathered in a sample of high school students from Arusha area, Tanzania (n = 286), and Kabwe area, Zambia (n = 272). The TPB determinants attitude towards condom use and subjective norm explain, respectively, 15.5% and 16.5% of the variance in condom use intention in Tanzania and Zambia, while self-efficacy is not significantly related to this intention in both countries. In most target (sub)groups from Tanzania and Zambia, the same TPB determinants predict condom use intention. Besides the TPB determinants, other variables are significantly related to condom use intention, such as sexual experience and gender. These results vary over the (sub)groups.

The findings of this study prove the utility and global applicability of the TPB on condom use intention in Tanzania and Zambia. Because most subgroups in both countries show the same TPB determinants of condom use intention, cost-effective overall HIV/AIDS prevention programmes can be developed that can easily be adapted for different subgroups in different countries.

Introduction

AIDS (Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome), caused by HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), is one of the most threatening diseases worldwide (UNAIDS, 2007). Sub-Saharan Africa, the area of Africa south of the Sahara desert, is the most affected region in the world, with AIDS being the leading cause of death in this area. Because relatively little is done on HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment, it is expected that the number of infected people and deaths will rise (UNAIDS, 2007).

HIV infection is often a consequence of a specific behaviour, one of which is unsafe sex (Fishbein, 2000). While condom availability has risen in Sub-Saharan Africa, there are many factors that keep people from using them (AVERT, 2007). Therefore, most HIV/AIDS prevention programmes aim at increasing the use of condoms in order to decrease the risk of infection and restrict the AIDS-epidemic (Bennett & Bozionelos, 2000).

Theoretically, scientific knowledge can contribute to the effectiveness of HIV/AIDS prevention programmes. While some studies found that behaviour change interventions that were explicitly based on theory were not more effective than prevention programmes without a theoretical basis (see Hardeman et al., 2002, for a review), other research showed a higher effectiveness of prevention programmes based on scientific literature (Fishbein, 2000; Gredig, Nideroest & Parpan-Blaser, 2006; Jemmott et al., 2007; Munoz-Silva, Sanchez-Garciá, Nunes & Martins, 2007). A commonly used behavioural model in scientific studies is Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991). According to the TPB, behaviour is best predicted by asking people whether they have the intention to show this specific behaviour. In turn, behavioural intention is determined by attitude, subjective norm, and self-efficacy. The current study on condom use intention in Tanzania and Zambia used the TPB as a theoretical foundation. Until now, a couple of studies on condom use intention applying the TPB have been conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa. Most of these were carried out in South Africa (Boer & Mashamba, 2007; Bryan, Kagee & Broaddus, 2006; Giles, Liddell & Bydawell, 2005; Jemmott et al., 2007). No studies using the TPB were conducted in Zambia yet, and only one study is available on Tanzania (Lugoe & Rise, 1999). The current study was carried out in Zambia and Tanzania to examine whether the results of studies conducted in South Africa are also valid for other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. The aim of the study is to examine determinants of condom use intention of Tanzanian and Zambian high-school students. Furthermore, the following subgroups will be compared to identify TPB determinants of intended condom use among specific target groups: males and females, students with and without a steady boy/girlfriend, and students with and without sexual experience. Subgroup analyzes to investigate whether the relation of attitude towards condom use, subjective norm, and selfefficacy to intention varies among specific target groups have hardly been reported in African studies. The research questions are:

* What are the differences between Tanzanian and Zambian high-school students in condom use intention, attitude towards condom use, subjective norm, and self-efficacy?

* What are the determinants of condom use intention of Tanzanian and Zambian high-school students?

* What are the determinants of condom use intention of males and females, students with and without a steady boy/girlfriend, and students with and without sexual experience?

The target group of this study is high-school students between 13 and 19 years old. Around this age most young people become sexually active and it is important to inform them timely and in the right way on safe sexual behaviour (UNAIDS, 2008a). Only a few prevention programmes in Africa focus on this group, even though the United Nations AIDS programme mentions studying young people as one of the most important goals of their prevention programme in Tanzania and Zambia (UNAIDS 2008a; UNAIDS 2008b). Respectively 11% and 13% of the Tanzanian males and females under study had sex before their 15th year. Of the Tanzanian young males and females (15-24 years old), respectively 81% and 36% had sex in the last 12 months, and 47% and 42% used a condom the last time they had sex (UNAIDS, 2008a). Only 44% of the Tanzanian young females correctly knows how to prevent an HIV infection, as does 49% of the Tanzanian young males.

Respectively 16% and 14% of the Zambian young males and females had sex before their 15th year. Respectively 86% and 30% of the Zambian young males and females had sex in the last 12 months, and 40% and 35% used a condom the last time they had sex. Of the Zambian young males, 37% correctly knows how to prevent an HIV infection, as does 34% of the Zambian young females (UNAIDS, 2008b; UNAIDS 2008c). The HIV prevalence rate in Tanzania is 8% compared to 22% in Zambia (Nyblade et al., 2003) and the percentage of HIV/AIDS-infected males and females is almost 50/50 in Tanzania, while three times more women thanman under 35 are HIV/AIDS-infected in Zambia (UNAIDS, 2006).

Theory of Planned Behaviour

The central behaviour in this study is condom use. How can the desired behaviour, condom use, be stimulated? To answer this question, insight into the factors that determine behaviour must be acquired (Lechner, Kremers, Meertens & De Vries, 2007). There are different theories and models; yet, many studies on condom use are based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). Studies that compared behavioural models showed that the TPB was significantly more efficient in predicting condom use than other behavioural models such as the health belief model, protection motivation theory, cognitive theory, and the information motivation-behavioural skills model (Bakker, Buunk & Siero, 1993; Chaisamrej, Zimmerman, Noar & Thomas, 2005). Moreover, the TPB is the most widely used model in studies on condom use intention (e.g., Armitage, Norman & Conner, 2002; Boer & Mashamba, 2007; Bryan et al., 2006; Bryan, Ruiz & O’Neil, 2003; Eun Seok, Kevin & Thema, 2007; Giles et al., 2005; Jemmott et al., 2007; Molla, Astrøm & Brehane, 2007; Munoz-Silva et al., 2007; Villarruel, Jemmott, Jemmott & Ronis, 2004; Wiggers, De Wit, Gras, Coutinho & Van den Hoek, 2003). Nevertheless, all these studies concluded that the TPB is not a perfect model and that possible expansions or improvements must be examined.

The TPB model can be explained by departing from the behaviour. Someone behaves in a certain way when that person has a strong intention to show that behaviour. Three behavioural determinants are underlying this behavioural intention: attitude towards the behaviour, subjective norm, and self-efficacy concerning the behaviour. Attitude is the general evaluation of the behaviour and is based on underlying beliefs that people have regarding pros and cons of the behaviour. Subjective norm refers to the perceived opinion of the social environment of a person regarding the desirability of his or her performance of the behaviour (Lechner et al., 2007). Self-efficacy is defined as the expectations that people have about their capability to perform a specific behaviour (Lechner et al., 2007). The behavioural intention to use a condom will be larger if a person has a positive attitude towards using a condom, if (s)he perceives that the social environment approves of using a condom and if (s)he expects to be capable of performing the behaviour. The relative influence of the three determinants can vary with the behaviour and population studied (Fishbein, 2000). A frequently voiced criticism on the TPB is that the model is not applicable to every culture because it is overly based on individualistic Western cultures. However, the TPB has been implemented successfully in more than fifty countries, developed as well as undeveloped ones (Fishbein, 2000). In every country, the three TPB determinants were the most important determinants of behavioural intention, although their values differed from country to country. The argument that the model is too individualistic therefore appears to be invalid, because even in a culture where group factors are known to be influential on someone’s behaviour (South Africa), the model explained as much as 67% of the behavioural intention (Giles et al., 2005).

Previous studies on condom use in sub-Saharan Africa

Several studies have been carried out on the applicability of the TPB on HIV/AIDS prevention in Sub-Saharan Africa, although most of them have been conducted in South Africa. The results showed that the TPB seems to be well applicable (For studies in South Africa, see Boer & Mashamba, 2005, 2007; Bryan et al., 2006; Giles et al., 2005; and Jemmott et al., 2007; For studies in Ethiopia, see Fekadu & Kraft, 2001, 2002; and Molla et al., 2007; For a study in Tanzania, see Lugoe & Rise, 1999). The variance in condom use intention among Sub-Saharan Africans could be explained from 22% (Boer & Mashamba, 2007) to 48% (Molla et al., 2007), and one study even explained 67% (Giles et al., 2005). All three TPB determinants were generally significantly related to condom use intention. The conclusion regarding the relative importance of the TPB determinants of condom use intention varied over these studies. When comparing the results from ten datasets as described in the nine above-mentioned articles (considering the males and females datasets of Boer and Mashamba (2007) and Bryan et al. (2006) as separate ones and the study reported by Fekadu and Kraft (2001, 2002) in two articles as one), attitude towards condom use appeared to be the most important determinant in two studies (Boer & Mashamba, 2007 for females; Molla et al., 2007), subjective norm in five studies (Boer & Mashamba, 2005; Boer & Mashamba, 2007 for males; Bryan et al., 2006 for males and females; Fekadu & Kraft, 2001, 2002), and self-efficacy in three studies (Giles et al., 2005; Jemmott et al., 2007; Lugoe & Rise, 1999). Only a few studies showed non-significant results for attitude towards condom use (Boer & Mashamba, 2005; Giles et al., 2005), subjective norm (Boer & Mashamba, 2007 for females; Jemmott et al., 2007) and self-efficacy (Boer & Mashamba, 2005; Boer & Mashamba, 2007 for males; Molla et al., 2007). These results show that a lot of variation in the importance of the TPB determinants was found in the different studies.

Condom use intention is not predicted solely by the TPB determinants. Therefore, it is recommended to take additional variables into account in order to explore their indirect or direct role in the TPB model (Fishbein, 2000; Lechner et al., 2007). In the above studies, some additional variables were significantly related as well: language preference (local language versus English, Jemmott et al., 2007), gender (Boer & Mashamba, 2007; Bryan et al., 2006), HIV knowledge (Bryan et al., 2006), and positive future outlook (Bryan et al., 2006).

Some variables were also considered important in previous studies on the TPB and condom use intention in Sub-Saharan Africa, but their relationship with condom use intention was not significant. We will further explore these variables in the current study. These are age (Bryan et al., 2006), HIV fear (Boer & Mashamba, 2007), sexual experience (Jemmott et al., 2007), and last condom use (Boer & Mashamba, 2007). In addition, following Boer and Mashamba (2007), religion was taken into account, because it was expected that Christians had a lower condom use intention. Several Christian denominations, in particular the Roman Catholic Church, do not approve of condom use (Bradshaw, 2003; Sarkar, 2008). Though never measured before, the residential area of respondents was also included because we had the impression that this might partly explain the differences in the results of earlier studies. For instance, urban areas showed a tendency towards rating self-efficacy as the most important determinant (e.g., Jemmott et al., 2007; Lugoe & Rise, 1999) whereas in rural areas attitude seemed to be more important than selfefficacy (e.g., Boer & Mashamba, 2007; Molla et al., 2007).

Finally, following the theorizing of Fishbein and Yzer (2003) three variables were added that might have a relationship with condom use intention, namely the attitudes towards specific goals. Attitudes towards specific goals are considered important because different goal attitudes might lead to different opinions about condom use. For example, people with an unfavourable attitude towards getting pregnant might hold a different opinion about condom use than people with a favourable attitude towards getting pregnant (Fishbein, 2000). In this study, three specific goals were distinguished that can be gained by performing, or not performing, the target behaviour of having sex with a condom: 1) getting pregnant; 2) experiencing pleasure; and 3) pleasing a partner.

Method

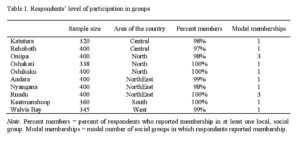

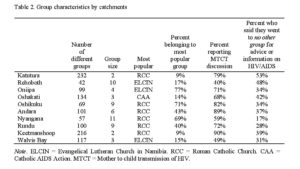

Data collection took place in April and May 2008. The participants were students from high schools in Arusha area, Tanzania, and Kabwe area, Zambia. Students and schools were found using a convenience sample. Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO’s) in Tanzania (Foundation Friends of Tanzania) and Zambia (Student Partnership Worldwide) that work together with schools assisted in the data gathering process by approaching high schools in their area and asking for permission to hand out the questionnaire. Three schools in Tanzania and two schools in Zambia were approached and they all agreed to participate. The questionnaire was translated into the national language of the countries. In Tanzania, this was Swahili and in Zambia this was English. After obtaining informed verbal consent, participants were given anonymous questionnaires. All students filled out the questionnaire within 45 minutes, and there was no non-response. The researcher and an interpreter were present in the classroom during the data collection. Confidentiality was assured in the questionnaire and the researcher repeated orally in class that all responses would remain anonymous.

Subjects

In Tanzania, 294 respondents completed the questionnaire whereas 273 respondents age of the respondents was 13 to 19 years old, respondents younger than 13 years old (i.e., eight in Tanzania and one in Zambia) were excluded, leaving 286 respondents in Tanzania and 272 in Zambia. The majority of the respondents were between 16 and 19 years old (85.7% in Tanzania and 79.8% in Zambia, respectively). Both in Tanzania and Zambia, the median age was 17 years. Of the Tanzanian respondents, 45.8% was female and of the Zambian respondents, 39.0% was female. In the Tanzanian sample, 22.7% reported that they had ever had sexual intercourse, of which 41.8% reported to have used a condom the last time they had sex. Of the Zambian respondents, 23.9% said they had ever had sexual intercourse, of which 39.7% used a condom the last time they had sex. Of the Tanzanian respondents, 81.0% reported to be Christian, 17.3% was Muslim, 1.0% was Hindu and 0.7% had another religion. Of the Zambian respondents, 98.9% reported to be Christian, 0.4% was Muslim, 0.4% was Hindu and 0.4% had another religion.

Differences between the Tanzanian and Zambian sample on the sociodemographic variables age, gender, and boy/girlfriend were examined using t-tests or chi-square tests. Results showed that the mean age of the Tanzanian respondents was slightly but significantly higher (16.95 versus 16.53 years) than that of the Zambian respondents, t = 2.385, p

Questionnaire

The four variables of the TPB were measured using scales that were used by Boer and Mashamba (2007). Because the Cronbach’s ± of the subjective norm scale in this questionnaire was 0.61, which is too low for a valid scale, the subjective norm scale was replaced by the one used by Fisher, Fisher, Bryan, and Misovich (2002), that showed a Cronbach’s ± of 0.79 in a South-African sample (Bryan et al., 2006). Condom use intention was measured with three items on a 5-point scale, for example, “in the future I will always use a condom” (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree, Cronbach’s ± = 0.69). Attitude towards condom use was measured with 13 items, each rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), Cronbach’s α = 0.88. An example of an attitude item is “using condoms will make sex less enjoyable”. Subjective norm was measured with eight items on a 5-point scale, for example, “friends that I respect think I should use condoms every time I have sex, during the next four months” (1 = very untrue, 5 = very true, Cronbach’s α = 0.86). The self-efficacy scale contains twelve 5-point items (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree, Cronbach’s α = 0.69). An example is “I think condoms are difficult to use”. A mean score was calculated for all variables measured with multiple items.

Variables that were not part of the TPB that were measured with existing questions were gender (0 = male, 1 = female), boy/girlfriend, sexual experience, language preference, religion, positive future outlook, HIV knowledge, and HIV fear. Boy/girlfriend was measured by asking “do you have a steady boyfriend/girlfriend” (0 = single, 1 = steady boyfriend/girlfriend) (Boer & Mashamba, 2007). Sexual experience was measured with the question “have you ever had sexual intercourse? (Male’s penis in a female’s vagina)” (Jemmott et al., 2007). Answering categories were: 0 = never had sexual intercourse, 1 = sexual intercourse at least once. In addition, last condom use was measured by the question “the last time I had sex, I used a condom” (1 = not applicable, 2 = yes, 3 = no) (Boer & Mashamba, 2007). Language preference was measured with one question based on Jemmott et al. (2007): “In general, what language do you read and speak?” (1 = only local, 5 = only English). This variable was recoded as follows: 0 = local language preference, 1 = both equal or English language preference. Positive future outlook was measured by 15 items (Cronbach’s α = 0.67) in accordance with Bryan et al. (2006). An example of a positive future outlook item is: “In general I am satisfied with myself” (1 = disagree a lot, 4 = agree a lot). HIV knowledge was measured by four items (Bryan et al., 2006). An example of an HIV knowledge item is: “AIDS is caused by the HIV virus” (0 = no, 1 = yes). A total score was calculated by administering one point for each correct answer (range 0-4). HIV fear was measured with three items (Cronbach’s α = 0.65) in accordance with Boer and Mashamba (2007). An example of an HIV fear item is: “I am afraid of contact with a person who is HIV positive” (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree).

Religion was measured by asking people about their religion (Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Hindu, traditional African religion, none). No respondents adhered to a traditional African religion. Because large parts of the Christian Church oppose condom use, whereas Muslim, Jewish and Hindu churches do not oppose condom use to this extent (Sarkar, 2008), religion was recoded into: 0 = religion with a ban on condom use, 1= religion with no explicit ban on condom use or no religion.

The ‘attitude towards goals’-items had not been used before in condom use studies and were therefore measured with self-designed questions. Attitudes towards three goals were discerned: attitude towards pregnancy (“I have sex because I want to get pregnant”), attitude towards having sex for own pleasure (“I have sex for pleasure”), and attitude towards having sex to please their partner (“I have sex to please my boyfriend/girlfriend”). These items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree). Finally, living area was examined by asking “in what area do you live?” (0 = rural, 1 = urban).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained on the socio-demographic characteristics and the determinants of intended condom use. Differences between the Tanzanian and Zambian mean scores of TPB determinants were calculated using a Students t-test. Furthermore, t-tests were conducted to examine differences between the Tanzanian and Zambian respondents on additional determinants of condom use intention, that is, goals attitudes, HIV knowledge, and HIV fear. These analyses were also done for the separate target groups in each country: males, females, singles, students with steady boy/girlfriend, and students with and without sexual experience. Next, the determinants were included in a multiple regression model using forced entry in blocks with condom use intention as dependent variable. The three blocks were:

1. TPB determinants (attitude towards condom use, subjective norm, and selfefficacy);

2. determinants that might be influenced by means of HIV/AIDS prevention programmes (attitude towards pregnancy, attitude towards own pleasure, attitude towards pleasing partner, HIV knowledge, and HIV fear); and

3. other additional variables (gender, age, boy/girlfriend, sexual experience, residential area, language preference, religion, and positive future outlook). We conducted separate regression analyses for the Tanzanian and the Zambian sample.

Religion was only entered in the Tanzanian analyses as 98.9% of the Zambian respondents was Christian. Finally, separate regression analyses were performed for the above mentioned subgroups in each country by adding the following variables in three blocks:

1. TPB determinants (attitude towards condom use, subjective norm, and self-efficacy);

2. Goal attitudes (attitude towards pregnancy, attitude towards own pleasure, and attitude towards pleasing partner);

3. gender, boy/girlfriend, and sexual experience. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 16.0.

Results

Differences between the Tanzanian and the Zambian sample

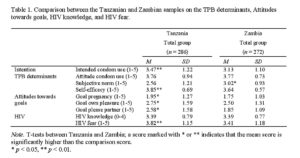

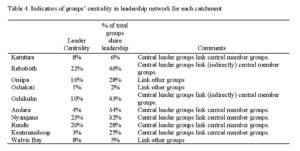

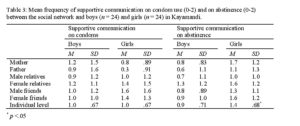

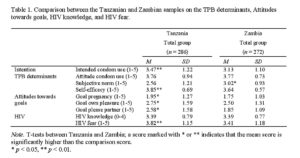

T-tests were calculated to estimate differences between the Tanzanian sample and the Zambian sample with regard to condom use intention, TPB determinants, and condom use related variables that might be influenced by means of HIV/AIDS prevention programmes. Table 1 shows that the Tanzanian students scored significantly higher than the Zambians on condom use intention, self-efficacy, attitude towards pregnancy, attitude towards having sex for own pleasure, attitude towards having sex to please partner, and HIV fear.

Table 1. Comparison between the Tanzanian and Zambian samples on the TPB determinants, Attitudes towards goals, HIV knowledge, and HIV fear. Note. T-tests between Tanzania and Zambia; a score marked with * or ** indicates that the mean score is significantly higher than the comparison score. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

On the other hand, Zambians scored significantly higher on subjective norm than Tanzanians. Due to the relatively large sample size, small differences between average scores can already be significant. When looking at relevant differences, considering a difference of > 0.40 (i.e., 10% of the range of the five-point scales) between the mean scores of Tanzanians and Zambians as clinically relevant, only subjective norm, attitude towards pleasing partner, and HIV fear showed relevant differences. The Zambian sample (M = 3.02) reported a higher average subjective norm than the Tanzanian sample (M = 2.56). The Tanzanian students scored higher on attitude towards having sex to please partner (M = 2.58) and HIV fear (M = 3.82) than the Zambian students (M = 1.85 and M = 3.41, respectively). The analyses were repeated for the target subgroups. The results of the subgroup analyses were comparable with those of the total Tanzanian and Zambian samples.

Predictors of condom use intention in Tanzania and Zambia

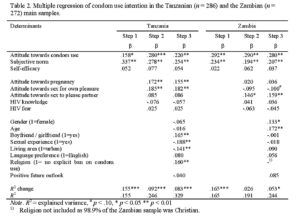

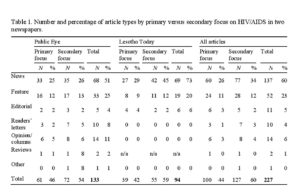

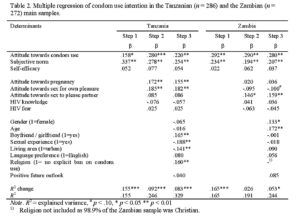

Regression analysis revealed that attitude towards condom use and subjective norm were predictive for condom use intention in both the Tanzanian and the Zambian sample (Table 2).

Table 2. Multiple regression of condom use intention in the Tanzanian (n = 286) and the Zambian (n =272) main samples. Note. R2 = explained variance, # p < .10, * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 1) Religion not included as 98.9% of the Zambian sample was Christian.

Regression analyses were conducted for each target group. The main results of the subgroup analyses are comparable with those of the total Tanzanian and Zambian sample.

Conclusion and discussion

This study examined the predictive power of the TPB on condom use intention amongst 13 to 19 year old high-school students in Tanzania and Zambia. The TPB has potential utility in predicting behavioural intention as the TPB determinants attitude towards condom use and subjective norm explained respectively 15.5% and 16.5% of the variance in condom use intention of Tanzanian and Zambian adolescents. The results of this study also show that attitude towards condom use and subjective norm are important determinants of condom use intention for almost all target groups that were examined in this study: males and females, students with and without a boy/girlfriend, and students with and without sexual experience. In all subgroups, subjective norm was identified as a significant determinant of condom use intention. Attitude towards condom use was significantly related to condom use intention in all subgroups except for two (i.e., the Tanzanian female group and the Tanzanian adolescents with a steady boy/girlfriend).

Determinants of condom use intention seem to exceed national borders, as subgroups from different countries have the same TPB determinants of condom use intention, despite the general idea that differences between (sub)populations can be expected (Fishbein, 2000). These findings prove the utility and global applicability of the TPB for studies on condom use intention, and thus support the findings of Fishbein (2000) who identified the TPB determinants as the most important determinants of behavioural intention in more than fifty studies. The results also give reason for optimism about possibilities to use elements of the same HIV/AIDS prevention programmes for subgroups in different countries. Future research has to focus on the possibility to use one HIV/AIDS prevention programme for, for instance, males in both Tanzania and Zambia. Only small local adaptations might be needed as several of the same behavioural determinants appear to be most important for target groups in both countries. This will reduce costs because the same programme can be implemented in more countries to a large extent.

Further research

into successful implementation of prevention programmes based on scientific studies is needed to reach successful and cost-effective pathways.

Differences in the TPB variables between target groups

Previous studies seldom compared the behavioural determinants of potential separate target groups, with the exception of comparisons between males and females (Boer & Mashamba, 2007; Bryan et al., 2006; Jemmott et al., 2007). With respect to Tanzanian and Zambian males, target subgroup analysis showed that attitude towards condom use and subjective norm were determinants of condom use intention among. This finding is consistent with the results of South African males in the study of Boer and Mashamba (2007), who used the same instruments to measure condom use intention, attitude, and self-efficacy. However, in our study attitude was more important than subjective norm, both in Tanzania and Zambia, whereas in the South African study of Boer and Mashamba (2007) subjective norm was more important. This difference might be explained by the instrument that was used to assess subjective norm. Boer and Mashamba (2007) measured subjective norm by means of the normative beliefs of six significant others, namely current sexual partner, new sexual partner, friends, parents, doctor, and public health campaigns (e.g., “my friends think that I should use condoms”) as well as motivation to comply with these significant others (e.g., “I care about the opinion of my friends”). The instrument we used only assessed the normative beliefs of the respondents’ boyfriend/girlfriend and friends. Taking the motivation to comply into account as well as various significant others might result in a higher predictive value of subjective norm. However, it must be noted that Bryan et al. (2006), using the same subjective norm instrument as we did, also found a higher predictive value for subjective norm than for attitude in their male sample. The results for females were slightly different. For them, subjective norm appeared to be the most important predictor of condom use intention in both our Tanzanian and Zambian sample. This is comparable with Bryan et al. (2006) and Fekadu and Kraft (2001, 2002), who found the same, but contrary to Boer and Mashamba (2007) who reported no significant relationship of subjective norm with condom use intention for the female sample.

Besides differences in the relevance of the subjective norm between men and women, we also found a clinically relevant difference in the mean scores of the subjective norm between the Tanzanian and the Zambian adolescents. The Zambian sample reported a higher average subjective norm than the Tanzanian sample. This could perhaps be explained by the fact that the city of the Tanzanian respondents (Arusha) is more developed than the city of the Zambian respondents (Kabwe). This is affirmed by the difference in the rural/urban rate between the Tanzanian sample (46/54) and the Zambian sample (80/20) and is in line with the survey by Masatu, Kvåle, and Klepp (2003) among 1,247 seventh grade pupils in the Arusha district. In this study, respondents’ friends did not feature as instrumental sources of reproductive health information, indicating that subjective norms of friends played a rather minor role in this area. Compared to their rural counterparts, urban dwellers may have different attitudes towards young people’s sexuality, which in turn may influence the way they communicate about reproductive health matters (Masatu et al., 2003), possibly resulting in a lower perceived social pressure.

Self-efficacy was not related to condom use intention in the total Tanzanian or the total Zambian sample. However, we found a borderline significant effect for Tanzanian females. This partly confirms our impression from previous studies that self-efficacy is more relevant in more urban areas in comparison with more rural areas. Previous studies on condom use intention in Southern Africa found mixed results. Similar to our findings, Boer and Mashamba (2005) and Molla et al. (2007) found no effect of self-efficacy. Boer and Mashamba (2007) found no effect of selfefficacy for males but a significant effect for females. Large effects were found by Jemmott et al. (2007) and Lugoe and Rise (1999). This variation in results is in line with the large differences between studies that were reported by meta-analyses on applications of the theory of planned behaviour to condom use. For example, Sheeran and Taylor reported a correlation between self-efficacy and intention that varied between .08 and .62. Overall, and akin to our results, meta-analyses reported that of the three TPB determinants self-efficacy had the smallest effect on condom use intention, though it must be noted that the average effect was larger than found in our study (Albarracín, Johnson, Fishbein, & Muellerleile, 2001; Sheeran & Taylor, 1999). A point of attention is that the small effect of self-efficacy in our study might be due to our operationalisation of self-efficacy. We used the same items that Boer and Mashamba employed (2005, 2007) and found largely identical results. Though we found no clear pattern in the different wordings of the selfefficacy items between the studies in Sub-Saharan Africa that might explain the variation in results, we cannot exclude that there might be some problem with the items we used. Alternatively, there might be a problem with the items that were used by the studies that found a large effect for self-efficacy. Therefore, future studies might further delve into the consequences of different operationalisations of selfefficacy.

It is noteworthy that in our study, self-efficacy had more effect on intention for Tanzanian women than for Tanzanian man. Similar findings were found in South Africa by Boer and Mashamba (2007). A potential explanation for this might be found in gender power imbalance, that is, self-efficacy is a determinant of condom use intention for females, and less for males, because of the gender power imbalance in sexual relations. Women do have to put more effort into negotiating condom use and this effort is to a large extent determined by self-efficacy (Albarracín, Kumkale, & Johnson, 2004; Boer & Mashamba, 2007). Despite the fact that gender power imbalance does exist in Zambia, women in Western Africa (this includes Zambia) have more control over sexual relationships than women in Southern Africa (Müller, 2005). Therefore, the reason that self-efficacy is not relevant for Zambian women might be that there is less gender power imbalance in Zambia. Future research has to examine to what extent gender power imbalance exists in different countries and how this influences the applicability of the TPB on males and females in sub-Saharan African countries.

To conclude, results for behavioural models are difficult to compare over studies due to variance in the studied populations (Lagarde et al., 2001). This is also shown by our comparison of all TPB studies on condom use intention in Sub-Saharan African countries, which showed that in each of the ten published datasets, different determinants were most important. Furthermore, comparisons are hampered by differences in the operationalisation of the variables. It is unclear whether different results can be explained by different populations or by the use of different items.

The current study is the first one to investigate determinants of condom use intention in two African countries with the same questionnaire. Overall, we found similar results in both countries and for most subgroups. As the use of the same questionnaire seems to lead to more comparable results, it is recommended to develop a standardised questionnaire for future research on the predictive power of the TPB in Africa. Ajzen (2006) gives an outline of how to construct a standardised TPB questionnaire. Importantly, keeping the main sentence structure of the items identical, his recommendations allow for local variations in the exact wording. For instance, certain perceived behavioural consequences or self-efficacy control issues might be more relevant in some countries or for some target groups. This can be taken into account without threatening the comparability of the studies. If a more standardised questionnaire is used in more studies, more cumulative knowledge on the behavioural determinants of condom use intention in Sub-Saharan Africa might be gathered.

Differences in the non-TPB variables between target groups

In the Tanzanian sample, but not in the Zambian sample, having a boy/girlfriend was positively related to a higher condom use intention. The positive effect of a steady relationship might be explained by the fact that having sex with a steady boy/girlfriend is more of a habitual behaviour than having sex with a casual partner.

People are more prepared for habitual sexual intercourse by buying condoms, carrying condoms, and communicating about condom use, which leads to a higher condom use intention (Van Empelen & Kok, 2006). It is unclear why the same was not found in the Zambian sample, but possibly cultural differences might play a role too. In future research, the relationship between societal differences and determinants of condom use should be further explored.

Goal attitudes (i.e., attitude towards having sex for own pleasure, attitude towards having sex to please partner, and attitude towards pregnancy) were significantly related to condom use intention in several subgroups, which raises the question what the underlying mechanisms are. For example, does the positive relationship for females between attitude to have sex in order to get pregnant and condom use intention imply that these adolescents want to wait with having a baby until they are older, and in the meantime want to prevent themselves from getting infected with HIV? There are some studies available on how using a condom influences sexual pleasure (e.g. Catania et al., 1991), but attitude towards pregnancy, attitude towards having sex for own pleasure, and attitude towards having sex to please partner were never measured before in an African study that applied the TPB to condom use intention. It is recommended to elaborate on the role of goal attitudes in future studies.

Tanzanians who adhere to a religion with a ban on condom use reported a lower condom use intention than respondents who have no religion or respondents who adhere to a religion with no explicit ban on condom use. This result can be explained by the Christian Church’ stance, particularly that of the Roman Catholic Church, on condom use (Bradshaw, 2003; Sarkar, 2008). Previous studies showed that religious behaviour is a strong predictor of sexual behaviour (Sarkar, 2008), although is it also indicated that the positive and negative effects of affiliation to conservative religious groups may rule each other out, that is, affiliation with conservative religious groups is more likely to delay sexual initiation, but also lowers the likelihood of condom use during first sex (Agha, Hutchinson & Kusanthan, 2006).

Additional variables that were significantly related to condom use intention in other studies (gender, HIV knowledge, positive future outlook, and language

preference) were not significantly related to condom use intention in the current study, except for gender. This is remarkable, because these variables were measured with exactly the same questions as used in previous studies (Bryan et al., 2006; Jemmott et al., 2007). However, as noted before, study results on determinants of condom use are difficult to compare. Therefore, it is recommended to explore different variables that could have a direct effect on condom use intention, in addition to the basic TPB model, for different countries and subgroups, as this might yield more in-depth insights.

Limitations

An important limitation of the current study is that the sample was not representative for all Tanzanian and Zambian adolescents between 13 and 19 years old. For example, the rural/urban rate, Christian/non-Christian rate, and high school attendance rate differ from the general rates of these countries. The rural/urban rate in Zambia is 60/40, whereas in our Zambian sample this rate is 80/20. The Tanzanian rural/urban rate is 64/36, whereas in our Tanzanian sample this rate is 46/54 (International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2008). Of the Tanzanian population, 30% is Christian (CIA, 2008), and 87% of the Zambian population (US Department of State, 2006), whereas in this study the percentage of Christians was respectively 81% and 99%. All respondents were high school students whereas only a selective group in both countries has the opportunity to go to high school (UNICEF, 2008a, 2008b).

We included religion in our study because several large Christian denominations oppose condom use, whereas most other religions are more liberal in this respect. However, in our survey we did not distinguish between Roman Catholics and Protestants. In Tanzania, about 60% of the Christians is Roman Catholic and in Zambia about 50% of the Christians is Roman Catholic (World Council of Churches, 2008). The Roman Catholic Church forbids the use of contraceptives, whatever the circumstances, but the Protestant churches (with a few exceptions) have developed a different interpretation, and generally emphasise birth control (Sarkar, 2008). Although both Catholics and Protestants promote the adoption of abstinence as an exclusive strategy for young people (Agha et al., 2006) and forbid premarital sex, these different interpretations might affect condom use intention. We found that condom use was lower among people who were members of one of the Christian churches. Most likely, had we been able to differ between the Catholic and Protestant churches, we would have found an even stronger difference between members of the Catholic Church and members of non-Christian churches. In future

studies, it is therefore recommended to include subdivisions of Christianity in the questionnaire.

Sexual experience was operationalised conform an earlier study on HIV/AIDS prevention (Jemmott et al., 2007), as ‘a male’s penis in a female’s vagina’. This

definition was chosen because it is the most common way to have sexual intercourse and we wanted to avoid that non-risky behaviour (e.g., masturbation) would be associated with sexual intercourse. As this is not the only way to have risky sexual intercourse, this definition might have biased the results on risky sexual behaviour. The current and previous studies show that the TPB can be used successfully to predict behavioural intention, but that it is not a perfect model yet. Although several additional explanatory factors were found, we did not examine all possible influences on condom use. For example, the Integrated Model on Behaviour Prediction (IMPB), a model that is related to the TPB, includes environmental constraints and personal skills (Fishbein & Yzer, 2003). The usefulness of the IMPB should be explored in future studies.

Finally, we did not study actual condom use. Meta-analyses on condom use showed that behavioural intention is one of the best determinants of condom use behaviour (e.g., Albarracín et al., 2001; Sheeran & Orbell, 1998). Although prospective studies that test the TPB with respect to the prediction of condom use behaviour in Sub-Saharan African countries are scarce, it is reasonable to assume that this also holds in these countries. In support, Bryan et al. (2006) found that intention was a significant predictor of behaviour among South African adolescents.

Implications for interventions

The findings of the current study have practical implications. HIV/AIDS prevention programmes in both Tanzania and Zambia should aim at the behavioural determinants that contribute significantly to condom use intention. Because most target subgroups have the same TPB determinants of condom use intention, development and implementation costs of prevention programmes can be reduced by using the same approach in both countries. For Tanzania and Zambia, this means that national HIV/AIDS prevention programmes should primarily target subjective norm and attitude towards condom use. These programmes should also take into account the additional non-TPB variables that are significantly related to condom use intention, which can differ for each target group in each country. Because they reported lower condom use intention, in Tanzania special attention should be paid to Tanzanians who are single, live in urban areas, are sexually active, and follow a religion that bans condom use. In Zambia, special attention should be paid to younger people and males. Nevertheless, during the research period in Tanzania and Zambia, it appeared that many NGOs, churches, schools, and politicians are still against condom use, and that they prohibit handing out condoms, for example at schools. As long as this policy does not change, fighting HIV/AIDS and increasing condom use will remain a challenge.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Tanzanian and Zambian respondents who were willing to complete our questionnaire. Furthermore, we would like to thank the Foundation Friends of Tanzania and SPW Zambia for all their efforts in the data gathering process. This study was financially supported by grants from the Jo Kolk Study fund and the AUV Foundation, to which we are very grateful for their donations.

References

Agha, S., Hutchinson, P., & Kusanthan, T. (2006). The effects of religious affiliation on sexual initiation and condom use in Zambia. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 550-555.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

Ajzen, I. (2006). Constructing a TPB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Retrieved from http://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf.

Albarracín, D., Johnson, B.T., Fishbein, M., & Muellerleile, P.A. (2001). Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 142-161.

Albarracín, D., Kumkale, G.T., & Johnson, B.T. (2004). Influences of social power and normative support on condom use decisions: A research synthesis. AIDS Care, 16, 700-723.

Armitage, C.J., Norman, P., & Conner, M. (2002). Can the theory of planned behavior mediate the effects of age, gender and multidimensional health locus of control? British Journal of Health Psychology, 7, 299-316.

AVERT. (2007). HIV and AIDS in Africa. Retrieved April 16, 2008 from http://www.avert.org/aafrica.htm.

Bakker, A., Buunk, B., & Siero, F. (1993). Condoomgebruik door heteroseksuelen [Condom use among heterosexuals]. Gedrag & Gezondheid, 21, 238-254.

Bennett, P., & Bozionelos, G. (2000). The theory of planned behavior as predictor of condom use: A narrative review. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 5, 307-326.

Boer, H., & Mashamba, M.T. (2005). Psychosocial correlates of HIV protection motivation among black adolescents in Venda, South Africa. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17, 590-602.

Boer, H., & Mashamba, M.T. (2007). Gender power imbalance and differential psychosocial correlates of intended condom use among male and female adolescents from Venda, South Africa. British Journal of Health Psychology, 12, 51-63.

Bradshaw, S. (2003, October 9). Vatican: Condoms don’t stop AIDS. The Guardian. Retrieved May 16, 2008 from http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2003/oct/09/AIDS.

Bryan, A., Kagee, A., & Broaddus, M.R. (2006). Condom use among South African adolescents: Developing and testing theoretical models of intentions and behavior. AIDS and Behavior, 10, 387-397.

Bryan, A., Ruiz, M.S., & O’Neil, D. (2003). HIV-related behaviors among prison inmates: A theory of planned behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 2565–2586.

Catania, J., Coates, T., Stall, R., Bye, L., Kegeles, S., Capell, F., et al. (1991). Changes in condom use among homosexual men in San Francisco. San Francisco: Center for AIDS Prevention Studies.

Chaisamrej, R., Zimmerman, R.S., Noar, S.M., & Thomas, L. (2005, May). A comparison of five social psychological models of condom use: Implications for designing prevention messages. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, New York. Retrieved April 27, 2008 from http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p14853_ index.html.

CIA. (2008). The world fact book. Retrieved April 7, 2008 from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2122.html.

Eun-Seok, C., Kevin, K.H., & Patrick, T.E. (2008). Predictors of intention to practice safer sex among Korean students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 641-651.

Fekadu, Z., & Kraft, P. (2001). Predicting intended contraception in a sample of Ethiopian female adolescents: The validity of the theory of planned behavior. Psychology & Health, 16, 207-222.

Fekadu, Z., & Kraft, P. (2002). Expanding the theory of planned behaviour: The role of social norms and group identification. Journal of Health Psychology, 7(1), 33-43.

Fishbein, M. (2000). The role of theory in HIV prevention. AIDS Care, 12, 273-278.

Fishbein, M., & Yzer, M.C. (2003). Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Communication Theory, 13, 164-183.

Fisher, J.D., Fisher, W.A., Bryan, A.D., & Misovich, S.J. (2002). Information-motivation behavioural skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychology, 21, 177-186.

Giles, M., Liddell, C., & Bydawell, M. (2005). Condom use in African adolescents: The role of individual and group factors. AIDS Care, 17, 729-739.

Gredig, D., Nideroest, S., & Parpan-Blaser, A. (2006). HIV-protection through condom use: Testing the theory of planned behavior in a community sample of heterosexual men in a high-income country. Psychology and Health, 21, 541-555.

Hardeman, W., Johnston, M., Johnston, D.W., Bonetti, D., Wareham, N.J., & Kinmonth, A.L. (2002). Application of the theory of planned behaviour in behaviour change interventions: A systematic review. Psychology and Health, 17, 123-158.

International Fund for Agricultural Development. (2008). World poverty map. Retrieved April 4, 2008 from http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org/english/regions/index.htm.

Jemmott, J.B., Heeren, G.A., Ngwane, Z., Hewitt, N., Jemmott, L.S., Shell, R., et al. (2007).

Theory of planned behavior predictors of intention to use condoms among Xhosa adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care, 19, 677-684.

Lagarde, E., Caraël, M., Glynn, J.R., Kanhonou, L., Abega, S.C., Kahindo, M., et al. (2001). Educational level is associated with condom use within non-spousal partnerships in four cities of Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS, 15, 1399-1408.

Lechner, L., Kremers, S., Meertens, R., & De Vries, H. (2007). Determinanten van gedrag [Determinants of behavior]. In J. Brug, P. Van Assema, & L. Lechner (Eds.), Gezondheidsvoorlichting en Gedragsverandering (pp. 75-106). Assen: Van Gorcum.

Lugoe, W., & Rise, J. (1999). Predicting intended condom use among Tanzanian students using the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Health Psychology, 4, 497-506.

Masatu, M.C., Kvåle, G., & Klepp, K.I. (2003). Frequency and perceived credibility of reported sources of reproductive health information among primary school adolescents in Arusha, Tanzania. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 31, 216-223.

Molla, M., Astrøm, A.N., & Brehane, Y. (2007). Applicability of the theory of planned behavior to intended and self-reported condom use in a rural Ethiopian population. AIDS Care, 19, 425-431.

Müller, T. (2005). HIV/AIDS, Gender and rural livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

Munoz-Silva, A., Sanchez-Garciá, M., Nunes, C., & Martins, A. (2007). Gender differences in condom use prediction with theory of reasoned action and planned behavior: The role of self-efficacy and control. AIDS Care, 19, 1177-1181.

Nyblade, L., Pande, R., Mathur, S., MacQuarrie, K., Kidd, R., Banteyerga, H., et al. (2003). Disentangling HIV and AIDS stigma in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia. Washington, D.C.: International Center for Research on Women [ICRW].

Sarkar, N.N. (2008). Barriers to condom use. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 13, 114-122.

Sheeran, P., & Orbell, S. (1998). Do intentions predict condom use? Meta-analysis and examination of six moderator variables. British Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 231-250.

Sheeran, P., & Taylor, S. (1999). Predicting intentions to use condoms: A meta-analysis and comparison of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29, 1624-1675.

UNAIDS. (2006). Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Retrieved April 10, 2008 from http://www.unAIDS.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/Default.asp.

UNAIDS. (2007). AIDS epidemic update. Retrieved April 10, 2008 from

http://www.unAIDSrstesa.org/Documents/press_centre/Complete_report_2007 UNAIDS. (2008a). Country situation analysis Tanzania. Retrieved April 11, 2008 from http://www.unAIDS.org/en/CountryResponses/Countries/tanzania.asp.

UNAIDS. (2008b). Zambia country report. Retrieved April 10, 2008 from http://data.unAIDS.org/pub/Report/2008/zambia2008country_progress_report_en.

UNAIDS. (2008c). Country situation analysis Zambia. Retrieved April 10, 2008 from http://www.unAIDS.org/en/CountryResponses/Countries/zambia.asp.

UNICEF. (2008a). Tanzanian statistics. Retrieved April 11, 2008 from http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/tanzaniastatistics.html#47.

UNICEF. (2008b). Zambian statistics. Retrieved April 11, 2008 from http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/zambiastatistics.html#46.

US Department of State. (2006). Zambia. Retrieved April 10, 2008 from http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2006/71331.htm

Van Empelen, P., & Kok, G. (2006). Condom use in steady and casual sexual relationships: Planning, preparation and willingness to take risks among adolescents. Psychology and Health, 21, 165-181.

Villarruel, A.M., Jemmott, J.B., Jemmott, L.S., & Ronis, D.L. (2004). Predictors of sexual intercourse and condom use intention among Spanish-dominant Latino youth. Nursing Research, 53, 172-181.

Wiggers, L.C.B., De Wit, J.B.F., Gras, M.J., Coutinho, R.A., & Van den Hoek, A. (2003). Risk behavior and social cognitive determinants among ethnic minority communities in Amsterdam. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15, 430-437.

World Council of Churches. (2008). Africa. Retrieved January 5, 2009, from http://www.oikoumene.org/en/member-churches/regions/africa/.

Introduction

Introduction