- by: Marcus Rolle & Alexandra Boutri

“We live in ominously dangerous times” stated the opening line of an article by C.J. Polychroniou (with Lily Sage) titled “A New Economic System for a World in Rapid Disintegration,” which was recently published in Truthout. And while the aforementioned piece was mainly a scathing critique of global neoliberal capitalism and a call for a new system of economic and social organization, its underlying thesis was that the world system is breaking down and that contemporary societies are in disarray.

“We live in ominously dangerous times” stated the opening line of an article by C.J. Polychroniou (with Lily Sage) titled “A New Economic System for a World in Rapid Disintegration,” which was recently published in Truthout. And while the aforementioned piece was mainly a scathing critique of global neoliberal capitalism and a call for a new system of economic and social organization, its underlying thesis was that the world system is breaking down and that contemporary societies are in disarray.

Is the (Western) world in shambles? We interviewed C.J. Polychroniou about the current world situation, with emphasis on developments in Europe and the United States, and sought his views on a host of pertinent political, economic and social issues, including the rise of the far right and the capitulation of the left.

Marcus Rolle and Alexandra Boutri: Let’s start by asking — what exactly do you have in mind when you say, “We live in ominously dangerous times?”

C.J. Polychroniou: We live in a period of great global complexity, confusion and uncertainty. It should be beyond dispute that we are in the midst of a whirlpool of events and developments that are eroding our capability to manage human affairs in a way that is conducive to the attainment of a political and economic order based on stability, justice and sustainability. Indeed, the contemporary world is fraught with perils and challenges that will test severely humanity’s ability to maintain a steady course towards anything resembling a civilized life.

For starters, we have been witnessing the gradual erosion of socio-economic gains in much of the advanced industrialized world since at least the early 1980s, along with the rollback of the social state, while a tiny percentage of the population is amazingly wealthy beyond imagination that compromises democracy, subverts the “common good” and promotes a culture of dog-eat-dog world.

The pitfalls of massive economic inequality were identified even by ancient scholars, such as Aristotle, and yet we are still allowing the rich and powerful not only to dictate the nature of society we live in but also to impose conditions that make it seem as if there is no alternative to the dominance of a system in which the interests of big business have primacy over social needs.

In this context, the political system known as representative democracy has fallen completely into the hands of a moneyed oligarchy which controls humanity’s future. Democracy no longer exists. The main function of the citizenry in so-called “democratic” societies is to elect periodically the officials who are going to manage a system designed to serve the interests of a plutocracy and of global capitalism. The “common good” is dead, and in its place we have atomized, segmented societies in which the weak, the poor and powerless are left at the mercy of the gods.

I contend that the above features capture rather accurately the political culture and socio-economic landscape of “late capitalism.” Nonetheless, the prospects for radical social change do not appear promising in light of the huge absence of unified ideological gestalts guiding social and political action. What we may see emerge in the years ahead is an even harsher and more authoritarian form of capitalism.

Then, there is the global warming phenomenon, which threatens to lead to the collapse of much of civilized life if it continues unabated. The extent to which the contemporary world is capable of addressing the effects of global climate change — frequent wildfires, longer periods of drought, rising sea levels, waves of mass migration — is indeed very much in doubt. Moreover, it is also unclear if a transition to clean energy sources suffices at this point in order to contain the further rising of temperatures. To be sure, global climate change will produce in the not-too-distant future major economic disasters, social upheavals and political instability.

If the climate change crisis is not enough to make one convinced that we live in ominously dangerous times, add to the above picture the ever-present threat of nuclear weapons. In fact, the threat of a nuclear war or the possibility of nuclear attacks is more pronounced in today’s global environment than any other time since the dawn of the atomic age. A multi-polar world with nuclear weapons is a far more unstable environment than a bipolar world with nuclear weapons, particularly if we take into account the growing presence and influence of non-state actors, such as extreme terrorist organizations, and the spread of irrational and/or fundamentalist thinking, which has emerged as the new plague in many countries around the world, including first and foremost the United States.

Read more

Photo: youtube.com

Participatory economics has long been proposed as an alternative to capitalism and centralized planning. It remains, nonetheless, a misunderstood concept and continues to find opposition among both capitalists and anticapitalists. So, what exactly is “participatory economics” and how does it fit with the socialist vision of a classless society? In this interview, Michael Albert, founder of Z Magazine and one of the leading advocates of the movement toward a “participatory society” addresses key questions about capitalism, socialism and the implications of a participatory economy.

C.J. Polychroniou: Any discussion of economic systems revolves essentially around two apparently opposed poles — capitalism and socialism. In reality, however, most of the actually existing economies in the modern world have been “mixed economies.” Be that as it may, what’s your understanding of capitalism, and what are the distinguished features of socialism?

Michael Albert: Capitalism is an economic system in which people own workplaces and resources, employ workers for wages to produce outputs and overwhelmingly employ market allocation to mediate how the outputs are dispersed. Typically also, and I would say inevitably if it has the first two features, it will also have what I call a corporate division of labor in which about 80 percent of the workforce does overwhelmingly rote, obedient and mainly disempowering tasks, and the other 20 percent monopolizes empowering tasks. Income will be a function of property and bargaining power.

In my view, there are, therefore, three main classes in capitalism: a working class doing the disempowering work [whose members] have low income and nearly no influence; a capitalist class that employs workers, sells their product and tries to reap profits, and which, due to those profits, enjoys tremendous wealth and dominant power; and a coordinator class situated between the other two, doing the empowering work, and, due to that, having the power to accrue high income and substantial influence.

Socialism is trickier to pinpoint. For some it is an economy in which those who produce decide all the outcomes, so it is classless, or, if you like, has only one class, the workers, all of whom have the same overall economic status. For others, socialism is a society with a polity that greatly influences economic outcomes on behalf of the public, even while owners still reap profits. For still others, socialism is an economy that has public or state ownership plus central planning or markets for allocation.

I think this last is what socialism in practice has been, plus having a corporate division of labor that arises inexorably due to its forms of allocation but is also preferred, plus an authoritarian polity. However, I call this type of economy “coordinatorism” for the clear and obvious reason that its institutions eliminate capitalist ownership but elevate the 20 percent coordinator class to ruling status. Out with the old boss: the owner, the capitalist class; in with the new boss: managers, doctors, lawyers and so on, the coordinator class.

So, if you like socialism because you hope for classlessness, you are pretty likely nowadays to have in mind some kind of worker-controlled economy but typically without offering clarification of what institutions can deliver that.

If you don’t like the idea of full classlessness — either fearing that it would be dysfunctional or wishing to maintain coordinator class advantages — as socialism, you likely have in mind some variant on classical Marxist coordinatorist formulations.

I prefer classlessness — which, in my mind, is like preferring freedom to servitude — but I also see a need to have an institutional vision able to give it substance, which is what participatory economics, or if you prefer, participatory socialism tries to provide.

Read more

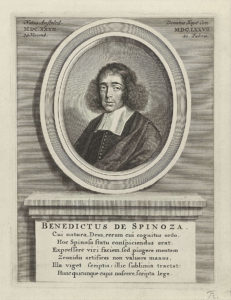

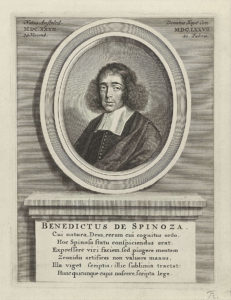

The Spinoza Web is a website that seeks to make the Dutch philosopher Benedictus de Spinoza (1632-1677) accessible to a wide range of users from interested novices to advanced scholars, and everything in between. It is a continually developing, active project whose success depends on its users. Please contact us with feedback, suggestions, and ideas!

The Spinoza Web is a website that seeks to make the Dutch philosopher Benedictus de Spinoza (1632-1677) accessible to a wide range of users from interested novices to advanced scholars, and everything in between. It is a continually developing, active project whose success depends on its users. Please contact us with feedback, suggestions, and ideas!

At present our website offers two points of entry. The ‘Timeline Experience’ tells the story of Spinoza, using rich graphic and other supporting material through which the user can navigate to enter and experience his very world. The ‘Database Search’ is a gateway to an enormous repository for the study of Spinoza, whose goal is eventually to assemble all first-hand documentation pertaining to him. Attractively designed without compromising on scholarly standards, our website promotes a source-based contextual approach to Spinoza who, revered and reviled, has had countless rumours and myths attached to his name over the course of the centuries.

‘Spinoza’s web’-project

The Spinoza Web is a creation of the ‘Spinoza’s Web’-project of the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Utrecht University, funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). It traces back to an early initiative of its main executive, Jeroen van de Ven, and was implemented by the project’s principal investigator, Piet Steenbakkers, who had entertained a long-time wish for a website dedicated to Spinoza. In 2014 postdoctoral researcher Albert Gootjes joined their ranks in a largely advisory capacity. Later that year the team commissioned the Rotterdam-based advertising agency Nijgh, which gladly welcomed the new challenge of combining creative inspiration with scholarly rigour.

Beta release

After extensive planning and user tests, November 2016 saw the beta release of The Spinoza Web, notably featuring the ‘Timeline Experience’ and Database with entries largely based on the historical and bibliographical research by Jeroen van de Ven. Subsequent releases are scheduled to boost the ‘Database Search’ by making available in open access Spinoza’s writings both in their original editions and in an authoritative English translation. Further plans include the addition of an interactive element facilitating Spinoza studies. To help us realize our pursuits, we welcome all contributions including but not limited to financial support. Potential contributors are encouraged to get in touch using the Contact page.

See: http://spinozaweb.org/

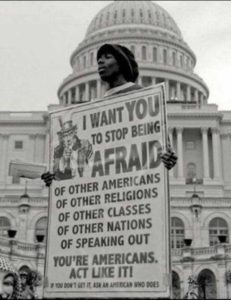

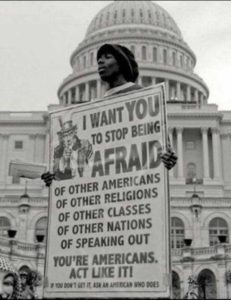

We see an organized anti worker, anti minority, anti immigrant, anti woman, anti LGBTQ, anti ecological, pro imperial, incarceration minded, surveillance employing, authoritarian reaction proliferating around the world. It calls itself right wing populist but is arguably more accurately termed neofascist. It preys on fear as well as often warranted anger. It manipulates and misleads with false promises and outright lies. It is trying to create an international alliance. Courageous responses are emerging and will proliferate around issue after issue, and in country after country. These responses will challenge the unworthy emotions, the vicious lies, and the vile policies. They will reject right wing rollback and repression. But to ward off an international, multi issue, reactionary assault shouldn’t we be internationalist and multi issue? Shouldn’t we reject reaction but also seek positive, forward looking, inspiring progress? To those ends:

We see an organized anti worker, anti minority, anti immigrant, anti woman, anti LGBTQ, anti ecological, pro imperial, incarceration minded, surveillance employing, authoritarian reaction proliferating around the world. It calls itself right wing populist but is arguably more accurately termed neofascist. It preys on fear as well as often warranted anger. It manipulates and misleads with false promises and outright lies. It is trying to create an international alliance. Courageous responses are emerging and will proliferate around issue after issue, and in country after country. These responses will challenge the unworthy emotions, the vicious lies, and the vile policies. They will reject right wing rollback and repression. But to ward off an international, multi issue, reactionary assault shouldn’t we be internationalist and multi issue? Shouldn’t we reject reaction but also seek positive, forward looking, inspiring progress? To those ends:

We stand for the growing activism on behalf of progressive change around the world, and their positive campaigns for a better world, and we stand against the rising reactionary usurpers of power around the world and their lies, manipulations, and policies.

We stand for peace, human rights, and international law against the conditions, mentalities, institutions, weapons and dissemination of weapons that breed and nurture war and injustice.

We stand for healthcare, education, housing, and jobs against war and military spending.

We stand for internationalism, indigenous, and native rights, and a democratic foreign policy against empire, dictatorship, and political and religious fundamentalism.

We stand for justice against economic, political, and cultural institutions that promote huge economic and power inequalities, corporate domination, privatization, wage slavery, racism, gender and sexual hierarchy, and the devolution of human kindness and wisdom under assault by celebrated authority and enforced passivity.

We stand for democracy and autonomy against authoritarianism and subjugation. We stand for prisoner rights against prison profiteering. We stand for participation against surveillance. We stand for freedom and equity against repression and control.

We stand for national sovereignty against occupation and apartheid. We oppose overtly brutal regimes everywhere. We oppose less overtly brutal but still horribly constricting electoral subversion, government and corporate surveillance, and mass media manipulation.

We stand for equity against exploitation by corporations of their workers and consumers and by empires of subordinated countries. We stand for solidarity of and with the poor and the excluded everywhere.

We stand for diversity against homogeneity and for dignity against racism. We stand for multi-cultural, internationalist, community rights, against cultural, economic, and social repression of immigrants and other subordinated communities in our own countries and around the world.

We stand for gender equality against misogyny and machismo. We stand for sexual freedom against sexual repression, homogenization, homophobia, and transphobia.

We stand for ecological wisdom against the destruction of forests, soil, water, environmental resources, and the biodiversity on which all life depends. We stand for ecological sanity against ecological suicide.

We stand for a world whose political, economic, and social institutions foster solidarity, promote equity, maximize participation, celebrate diversity, and encourage full democracy.

We will not be a least common denominator single issue or single focus coalition. We will be a massive movement of movements with a huge range of concerns, ideas, and aims, united by what we stand for and against.

We will enjoy and be strengthened by shared respect and mutual aid while we together reject sectarian hostilities and posturing.

We stand for and pledge to work for peace and justice.

We the initial signers of this “We Stand” statement, listed to the left of this page, upon reaching a critical mass of total signers will consult all signers and collectively discuss and use vote tallying from all signers to join with many other emerging efforts to arrive at more specific demands for warding off reaction, winning worthy gains in the present, and developing grounds upon which to pursue more fundamental changes in the future.

Gaining further numbers, we will all together begin, if we haven’t already, coalescing with our neighbors and work and schoolmates to explore how to best fight against reaction and for our positive demands.

After culling significant shared experiences if possible we will begin to hold gatherings and even conventions in our various countries to join with others to create lasting organizational vehicles and program to continue pursuing our collective agendas.

We initial signers, will seek support, promote unity, and collectively facilitate the emergence of effective means for collective participatory policy-making and program development by all signers as best we can.

Go to: https://www.standforpeaceandjustice.org/

The United States is rapidly declining on numerous fronts — collapsing infrastructure, a huge gap between haves and have-nots, stagnant wages, high infant mortality rates, the highest incarceration rate in the world — and it continues to be the only country in the advanced world without a universal health care system. Thus, questions about the nature of the US’s economy and its dysfunctional political system are more critical than ever, including questions about the status of the so-called American Dream, which has long served as an inspiration point for Americans and prospective immigrants alike. Indeed, in a recent documentary, Noam Chomsky, long considered one of America’s voices of conscience and one of the world’s leading public intellectuals, spoke of the end of the American Dream. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Chomsky discusses some of the problems facing the United States today, and whether the American Dream is “dead” — if it ever existed in the first place.

The United States is rapidly declining on numerous fronts — collapsing infrastructure, a huge gap between haves and have-nots, stagnant wages, high infant mortality rates, the highest incarceration rate in the world — and it continues to be the only country in the advanced world without a universal health care system. Thus, questions about the nature of the US’s economy and its dysfunctional political system are more critical than ever, including questions about the status of the so-called American Dream, which has long served as an inspiration point for Americans and prospective immigrants alike. Indeed, in a recent documentary, Noam Chomsky, long considered one of America’s voices of conscience and one of the world’s leading public intellectuals, spoke of the end of the American Dream. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Chomsky discusses some of the problems facing the United States today, and whether the American Dream is “dead” — if it ever existed in the first place.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, in several of your writings you question the usual view of the United States as an archetypical capitalist economy. Please explain.

Noam Chomsky: Consider this: Every time there is a crisis, the taxpayer is called on to bail out the banks and the major financial institutions. If you had a real capitalist economy in place, that would not be happening. Capitalists who made risky investments and failed would be wiped out. But the rich and powerful do not want a capitalist system. They want to be able to run the nanny state so when they are in trouble the taxpayer will bail them out. The conventional phrase is “too big to fail.”

The IMF did an interesting study a few years ago on profits of the big US banks. It attributed most of them to the many advantages that come from the implicit government insurance policy — not just the featured bailouts, but access to cheap credit and much else — including things the IMF researchers didn’t consider, like the incentive to undertake risky transactions, hence highly profitable in the short term, and if anything goes wrong, there’s always the taxpayer. Bloomberg Businessweek estimated the implicit taxpayer subsidy at over $80 billion per year.

Much has been said and written about economic inequality. Is economic inequality in the contemporary capitalist era very different from what it was in other post-slavery periods of American history?

The inequality in the contemporary period is almost unprecedented. If you look at total inequality, it ranks amongst the worse periods of American history. However, if you look at inequality more closely, you see that it comes from wealth that is in the hands of a tiny sector of the population. There were periods of American history, such as during the Gilded Age in the 1920s and the roaring 1990s, when something similar was going on. But the current period is extreme because inequality comes from super wealth. Literally, the top one-tenth of a percent are just super wealthy. This is not only extremely unjust in itself, but represents a development that has corrosive effects on democracy and on the vision of a decent society.

What does all this mean in terms of the American Dream? Is it dead?

The “American Dream” was all about class mobility. You were born poor, but could get out of poverty through hard work and provide a better future for your children. It was possible for [some workers] to find a decent-paying job, buy a home, a car and pay for a kid’s education. It’s all collapsed — and we shouldn’t have too many illusions about when it was partially real. Today social mobility in the US is below other rich societies.

Is the US then a democracy in name only?

The US professes to be a democracy, but it has clearly become something of a plutocracy, although it is still an open and free society by comparative standards. But let’s be clear about what democracy means. In a democracy, the public influences policy and then the government carries out actions determined by the public. For the most part, the US government carries out actions that benefit corporate and financial interests. It is also important to understand that privileged and powerful sectors in society have never liked democracy, for good reasons. Democracy places power in the hands of the population and takes it away from them. In fact, the privileged and powerful classes of this country have always sought to find ways to limit power from being placed in the hands of the general population — and they are breaking no new ground in this regard. Read more

Andrew Bacevich ~ Photo: democracynow.org

Since the end of the Cold War, the US has been the only true global superpower, with US policymakers intervening freely anywhere around the world where they feel there are vital political or economic interests to be protected. Most of the time US policymakers seem to act without a clear strategy at hand and surely without feeling the need to accept responsibility for the consequences of their actions. Such is the case, for instance, with the invasion of Iraq and the war in Afghanistan. US policymakers also seem to be clueless about what to do with regard to several “hot spots” around the world, such as Libya and Syria, and it is rather clear that the US no longer has a coherent Middle East policy.

What type of a global power is this? I posed this question to retired colonel and military historian Andrew Bacevich, a Boston University professor who has authored scores of books on US foreign and military policy, including America’s War for the Greater Middle East, Breach of Trust, and The Limits of Power. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Bacevich explains how the militaristic nature of US foreign policy is a serious impediment to democracy and human rights.

C.J. Polychroniou: I’d like to start by asking you to outline the basic principles and guidelines of the current national military strategy of the United States.

Andrew Bacevich: There is no coherent strategy. US policy is based on articles of faith — things that members of the foreign policy establishment have come to believe, regardless of whether they are true or not. The most important of those articles is the conviction that the United States must “lead” — that the alternative to American leadership is a world that succumbs to anarchy. An important corollary is this: Leadership is best expressed by the possession and use of military power.

According to the current military strategy, US forces must be ready to confront threats whenever they appear. Is this a call for global intervention?

Almost, but not quite. Certainly, the United States intervenes more freely than any other nation on the planet. But it would be a mistake to think that policymakers view all regions of the world as having equal importance. Interventions tend to reflect whatever priorities happen to prevail in Washington at a particular moment. In recent decades, the Greater Middle East has claimed priority attention.

What’s really striking is Washington’s refusal or inability to take into account what this penchant for armed interventionism actually produces. No one in a position of authority can muster the gumption to pose these basic questions: Hey, how are we doing? Are we winning? Once US forces arrive on the scene, do things get better?

The current US military strategy calls for an upgrade of the nuclear arsenal. Does “first use” remain an essential component of US military doctrine?

It seems to, although for the life of me I cannot understand why. US nuclear policy remains frozen in the 1990s. Since the end of the Cold War, in concert with the Russians, we’ve made modest but not inconsequential reductions in the size of our nuclear arsenal. But there’s been no engagement with first order questions. Among the most important: Does the United States require nuclear weapons to maintain an adequate deterrent posture? Given the advances in highly lethal, very long range, very precise conventional weapons, I’d argue that the answer to that question is, no. Furthermore, as the only nation to have actually employed such weapons in anger, the United States has a profound interest and even a moral responsibility to work toward their abolition — which, of course, is precisely what the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty obliges us to do. It’s long past time to take that obligation seriously. For those who insist that there is no alternative to American leadership, here’s a perfect opportunity for Washington to lead.

Does the US have, at the present time, a Middle East policy?

Not really, unless haphazardly responding to disorder in hopes of preventing things from getting worse still qualifies as a policy. Sadly, US efforts to “fix” the region have served only to make matters worse. Even more sadly, members of the policy world refuse to acknowledge that fundamental fact. So we just blunder on.

There is no evidence — none, zero, zilch — that the continued U.S. military assertiveness in that region will lead to a positive outcome. There is an abundance of evidence pointing in precisely the opposite direction.

Was the US less militaristic under the Obama administration than it was under the Bush administration?

It all depends on how you define “militaristic.” Certainly, President Obama reached the conclusion rather early on that invading and occupying countries with expectations of transforming them in ways favorable to the United States was a stupid idea. That said, Obama has shown no hesitation to use force and will bequeath to his successor several ongoing wars.

Obama has merely opted for different tactics, relying on air strikes, drones and special operations forces, rather than large numbers of boots on the ground. For the US, as measured by casualties sustained and dollars expended, costs are down in comparison to the George W. Bush years. Are the results any better? No, not really.

To what extent is the public in the US responsible for the uniqueness of the military culture in American society?

The public is responsible in this sense: The people have chosen merely to serve as cheerleaders. They do not seriously attend to the consequences and costs of US interventionism.

The unwillingness of Americans to attend seriously to the wars being waged in their names represents a judgment on present-day American democracy. That judgment is a highly negative one.

What will US involvement in world affairs look like under the Trump administration?

Truly, only God knows.

Trump’s understanding of the world is shallow. His familiarity with the principles of statecraft is negligible. His temperament is ill-suited to cool, considered decision making.

Much is likely to depend on the quality of advisers that he surrounds himself with. At the moment, he seems to favor generals. I for one do not find that encouraging.

Copyright, Truthout.

Andrew J. Bacevich is Professor of International Relations and History at Boston University. A graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, he received his PhD in American Diplomatic History from Princeton University. Before joining the faculty of Boston University, he taught at West Point and Johns Hopkins.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, the political economy of the United States and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published several books and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Croatian, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish.