If the world had any ends, British Honduras would certainly be one of them. It is not on the way from anywhere to anywhere else’ (Aldous Huxley 1984:21).

If the world had any ends, British Honduras would certainly be one of them. It is not on the way from anywhere to anywhere else’ (Aldous Huxley 1984:21).

When I had to do fieldwork in the Caribbean region for my final research several years ago, someone from the department of cultural Anthropology in Utrecht in the Netherlands asked me why I didn’t go to Belize. My answer to his question was at that time quite significant: ‘Belize??’ I had no idea where it was and could not picture it at all.

Libraries that I visited in the Netherlands hardly provided any solace. Most of the books on Central America hardly mentioned Belize. Booth and Walker describe the position of the country as follows in ‘Understanding Central-America’: ‘Though Belize is technically Central America, that English-speaking microstate has a history that is fairly distinct from that of the other states in the region. At present this tiny republic, which only became formally independent from Great-Britain in 1981, does not figure significantly in the ‘Central American’ problem’ (1993:3).

Multi-Ethnic Belize

The fact that Belize receives little attention in literature on Central America underlines the peripheral position of the country in this region. Some authors qualify it as part of the Caribbean world; others primarily see Belize as a member of the British Commonwealth. Besides that it is also seen as part of the Central American context. The Formation of a colonial Society (1977) by the English sociologist Nigel O. Bolland was the first scientific work on Belize that I was able to acquire. The Belize Guide (1989) by Paul Glassman provided me with a tourist orientated view of this ‘wonderland of strange people and things’ (Glassman 1989:1). Collecting sustaining literature was and remains a tiresome adventure. Slowly but surely my list of literature expanded.

My knowledge of the region was limited. Reactions from others also confirmed that Belize is a country with a slight reputation. For example, I still remember being corrected by someone from a travel agency. After asking the gentleman if a direct flight to Belize existed, he answered somewhat pityingly: ‘Sir, you must mean Benin´. In my circle of friends, Belize also turned out to be unheard of. The neighboring countries Guatemala and Mexico are better known. An important reason for this is that the media informs people of the most important happenings in these countries. This information is often clarified using maps of the area on which Guatemala and Mexico, but also Belize, are marked. Nonetheless, time and time again Belize turns out to be a country that does not appeal to the imagination.

The comments I heard from tourists coming in from Mexico or Guatemala are notable. ´This is a culture shock´, ´where are the Indians´, ´this doesn´t look at all like Central America´, ´it´s surprising how well you can get by with English here, that was not like that at all in Mexico´. Many of the tourists that come from Mexico quickly go through Belize city on their way to one of the islands off the coast of Belize where they relax for a few days before going to Guatemala. Most of the tourists coming into Belize from Tikal (Guatemala) spend a night in San Ignacio, comment on the fact that everything is so expensive, and quickly travel on to Chetumal (Mexico) the next day.

Belize is a country that lies hidden between two countries with a certain reputation. I do not really think that it is an exaggeration to state that Belize is something of a fictitious end of the world, as formulated by Huxley. In order to obtain an impression of the country, in which this research took place, the next section gives a general idea of the topographic and climatic characteristics. Besides that, the compilation of the population, the constitutional and political situation, the economic position, the religious context and the multi-lingual structure of the country are discussed successively. Furthermore, it is essential to provide an outline of the historic context in which the various ethnic groups in Belize have taken in their place. In other words: How has this country come to be so multi-ethnic?

Belize, A Central American Country on the Periphery

On 21 September 1981, the former British Honduras becomes independent. This date is the formal end of a process of independence that took seventeen years. In 1964, British Honduras of the time received the right to an internal self-government and in 1973 the name of the country was changed to Belize. With an area of 22,965 km2, Belize is the second smallest country in Central America. El Salvador is smaller (21,393 km2), but has considerably more inhabitants with it’s population of 5.889,000. According to the census of 1991, Belize has just 189,392 (Central Statistical Office 1992). This comes down to eight inhabitants per square kilometer, whereas El Salvador has 275 inhabitants per square kilometer. With that, the two countries are each other’s opposites in Central America, Belize is the most sparsely populated and El Salvador the most densely.

Belize

Geography

Belize borders on Mexico in the north, on Guatemala in the west and the south, and on the east the country borders on the Caribbean Sea. The area along the coast consists mostly of marshland with dense mangrove forests, mouths of rivers, lagoons and, every now and again, a sandy beach. Countless small and large rivers, that have played a crucial part in the infrastructure throughout the centuries, run through the country. Much of the wood chopped in the inland found and finds its way towards its destination at the coast via these waterways. It can rain abundantly in Belize in the months May to November, especially in the south, and then the waterways swell up to become rapid rivers.

Climate

The climatic conditions in Belize vary from tropical in the south to subtropical in the north. The climate is warm and the temperature varies between twenty-seven and forty degrees Celsius. It was especially the humidity, with an average of 85% in the southern part of the country that drew heavily on the physical condition of this researcher. The country officially has two seasons. The dry season, that lasts from November to June, and the wet season from June to November. During the wet season, tropical depressions regularly develop in the Caribbean region that reveal themselves as hurricanes. For this reason, this season is also called the hurricane season. This destructive force of nature has hit Belize several times in this century. The hurricanes of 1931, 1955 and 1961 have not failed to leave behind a trail of disaster.

The season in which it is relatively dryer than the rest of the year takes up a few months in the north (February to May), while in the south it only lasts several weeks (Dobson 1973:4). In fact, there is no telling what the weather will do in Belize. A Belizean friend of mine says the following on this matter: ‘We have two seasons here, a dry and a wet season; they generally take place on one and the same day’.

Topography

Belize can be split up into four topographically different areas, the north, the center, the south and the barrier reef off the coast. The river, Rio Hondo, forms the border with Mexico. The northern part of the country is low-lying, quite flat and is dotted with small rivers and lakes. This area is characterized by extensive farming (sugar beet among others).

The central part of Belize has a more hilly appearance. This region was once the border of the rainforest that used to reach further to the south. Lately, the landscape has changed so dramatically through the reclamation of the rainforest, that it has become a separate topographic area. The reclaimed terrain is used as grassland for cattle farms. The newly available ground is also planted with orange and grapefruit trees.

The south is the most uncultivated area in the country. Along the coast, there is a strip of low-lying land through which the Southern Highway runs. In this area small-scaled, intensive farming takes place. Further inland the difference in altitude is larger. This is the terrain of the rainforests, the Mountain Pine Ride and the Maya Mountains with the Victoria Peak as highest point (1120 meters). In the south of Belize the Sarstoon River forms the border with Guatemala.

The fourth topographic region is formed by the barrier reef off the Belizean coast. This is a long-drawn-out area of coral reefs. These coral reefs come up above the water in many places and form chains of ‘exotic’ islands that, in Belize, are called ‘cayes’ and are the largest attraction for tourists.

The Population

The country has a multi-ethnic population. According to the 1991 census, it is demographically compiled as follows: Mestizos (43.6%), Belizean Creoles (29.8%), Garinagu (6.6%), Kekchi Maya’s (4.3%), Mopan Maya’s (3.7%), all other Maya’s (3.1%), East Indians (3.5%), Mennonites (3.1%) and a remainder consisting of Lebanese and Syrians, often called Lebanese in popular speech (0.1%), Chinese (0.4%), ‘Whites’ (0.8%) and others (1.0%). Besides the 189,392 inhabitants, the country shelters approximately 26.000 refugees from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador (Central Statistical Office 1992). It is assumed that the number of refugees is higher in reality, because large areas of Belize are practically uninhabited, so they are difficult to check. Besides that, large landowners like to make use of refugees: they are cheap workers and can be tied to them for a longer time through the debt-peonage system. It doesn’t bother the large landowners if the refugees stay in the country legally or illegally, as long as they are cheap. Among the population, there are many prejudices against these Spanish speakers, who are dimply called ‘aliens’ by the Belizeans.

Form of Government and Political System

Until 1981, obtaining independence was an important national point of discussion. Those for and against independence fought each other with social-economic and political arguments. The fear for a possible military invasion by Guatemala unleashed several collective sentiments. The Belizeans felt threatened. Through this a national sense of unity arose despite different political, social-economic and ethnic backgrounds. Based on this, the Belizeans reacted against the colonial power, the British Kingdom, and the neighboring Guatemala.

After achieving independence in 1981, Belize remained a member of the British Commonwealth. Like most English-speaking Caribbean countries, it is a constitutional monarchy. Formally, the head of state is the British queen; she is represented by a governor-general who, by constitution, must be Belizean by nationality. In practice, this form of government comes down to the fact Belize is sovereign and that the relationship with the British Kingdom is one of ceremonial traditions. Belize has a polity according to the Westminster model. The executive power is in the hands of the governor-general, the Prime Minister and the cabinet. The National Assembly and a bicameral institute consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives hold the legislative power. The Senate consists of eight appointed members. Five senators are appointed by the Prime Minister, two by the head of the opposition party and one by the governor-general. The House of Representatives has 28 representatives that are chosen directly. Furthermore, Belize has an independent judicial power.

In Belize a multi-party system is operative, based on the typical British electoral system. This means that since the independence, two parties have dominated. The People’s United Party (PUP) and the United Democratic Party (UDP). The PUP is a center-left orientated party that is lead by the charismatic George Price. This party has always had strong ties with the union movement, which was the first to resist the British colonial dominion. The UDP of the current Prime Minister follows a center-right political course. This party was founded by the conservative ‘slightly-colored Creole’ establishment with strong pro-British sentiments. The UDP stands for a policy in which free enterprise is stimulated and the free market policy is at the forefront. The first general elections in Belize were held in 1954. The second followed three years later. Between 1957 and 1969 the population voted one every four years. Since 1969 the representative body of the people is chosen every five years.

The political parties in Belize strive for national unification. However, the census clearly shows that Belize is a multi-ethnic society. The internal problems that arise because of this are latently present in Belize, but up until now they do not seem to have a determining role in the political and social-economic sphere.

Economy

Belize is situated in the economic arena of the third world (Clegern 1988:11-4). In spite of this, the economic position is quite favorable in comparison to countries like El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua; a reason for many Belizeans to assume that refugees are more likely to have economic rather than political motivations. After the PUP had stipulated that Belize would receive both internal and external self-rule during the negotiations on independence in 1980, the country had to deal with many economic setbacks once it had acquired independence. In this period Belize’s export was consisted mainly of products from the agricultural industry, such as sugar, molasses, citrus fruits and bananas. Due to the high oil prices, low sugar prices and declining world market, the country was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1981 (Barry 1992:39).

Belize is situated in the economic arena of the third world (Clegern 1988:11-4). In spite of this, the economic position is quite favorable in comparison to countries like El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua; a reason for many Belizeans to assume that refugees are more likely to have economic rather than political motivations. After the PUP had stipulated that Belize would receive both internal and external self-rule during the negotiations on independence in 1980, the country had to deal with many economic setbacks once it had acquired independence. In this period Belize’s export was consisted mainly of products from the agricultural industry, such as sugar, molasses, citrus fruits and bananas. Due to the high oil prices, low sugar prices and declining world market, the country was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1981 (Barry 1992:39).

Today, Belize is almost completely dependent on the economic situation in the United States. A large part of the farming products is exported there. The Belizean tourist industry primarily focuses on the North American market. Furthermore, many Belizeans are partially dependent on the money that is sent to them by family members who have migrated. Due to the fact that the Belizean dollar is linked to the US dollar, an economic setback in the United States hits Belize hard. This makes Belize very fragile economically. Furthermore, the country has a large national debt to the IMF because of its near bankruptcy in 1981. In an attempt to protect employees, the government has introduced a minimum wage of 1.25 Belizean dollars per hour. In 1990 the average annual income per person was 1600 Belizean dollars (Barry 1992:48).

The census of 1991 estimated the supply of labor to be 65.000 people of which 20% was unemployed at the time (Central Statistical Office 1992). These numbers give, in my opinion, an inaccurate picture of the actual situation. A large group of employees in Belize is dependent on the many service and government institutions in the country. Furthermore, much of the labor supply works in the seasonal labor. This means that many employees have to work as day laborers during certain periods per year so they are not certain of a fixed income. The difference between rich and poor that is continually becoming more visible and the unrest that is caused by a chronic shortage of employment are causing much dissatisfaction.

Religions

Belize is a multi-religious society. The census of 1991 distinguishes fourteen different religious movements. The Catholic Church is by the far the best-represented in Belize with 57.7%. Compared to its neighbors, Mexico (92%) and Guatemala (95%), this number is low. The Catholic faith was not introduced in Belize by the Spanish, but by the immigrants from Mexico. North American Jesuits developed a hardy church infrastructure in Belize (Barry 1992;113). Besides Catholicism, the Anglican Church (6.9%), the Pentecostal church (6.3%), Methodists (4.2%), Adventists (4.1%), Mennonites (4%), Hindus (2.5%), Nazarenes (2.5%), Jehovah’s Witnesses (1.4%) and 4.3% other religious movements’ (Baptists, Bahai, Mormons, Moslems and the Salvation Army) are active in Belize. Six percent of the population state that they have no religion (Central Statistical Office 1992).

Languages

English is the official language in Belize, but several other languages are also spoken. Almost every ethnic group has its own language. English is the lingua franca of the country (Troy Lopez 1991:18). This language is often associated with the colonial past and with the Belizean elite. Even though English is the official language; a large part of the population speaks Belizean-Creole or Spanish. According to the census of 1991, 54.3% of the population speaks English well, 45.7% speaks it poorly or not at all. The census also shows that 43.8% of the population speaks Spanish well while 56.2% speaks it poorly or not at all (Central Statistical Office 1992).

The Belizean-Creole is the everyday-language for the Creoles in Belize. Especially the Afro-Belizean group of the population in the Stann Creek District and the densely populated Belize District use this language. The second everyday-language, Spanish, is on the rise and is spoken in large parts of Corozal, Orange Walk, Cayo and Toledo. Spanish is the language of Belizean Mestizos that do not live in Belize District ore have not grown up there. Percentages on other languages that are spoken by the various ethnic groups in Belize are not reported in the census. They are languages such as Mopan, Kekchi, Low German and various kinds of Chinese. The Belizean Garinagu primarily live in the Stann Creek District and the Toledo District. This ethnic group has its own language, Garifuna. In the cities and villages where the Garinagu live, Garifuna is spoken. In Dangriga Creole-English is spoken alongside Garifuna. The senior Garinagu complain that the young Garinagu no longer have any knowledge of their language and that they are involved with a language that, in their eyes, is not a real language. By contrast, in the Garifuna villages, Garifuna is still the primary language. The children first learn Garifuna at home and then later are taught English at primary school. In the rural areas of the Toledo District, Mopan and Kekchi Maya are spoken. The Mennonites, who have their farming areas in the Cayo and Orange Walk District, communicate in Low German.

The Garinagu’s Religious System

‘If a single factor can be cited for the weakening of traditional institutions of family, church, and community, it is that they have been divested of many of the functions that once justified their existence and bound individuals to them.’

‘It is Monday August 20, 1990, the dugu is in full swing, various woman are in trance, the three drummers are following the movements of the buyai, in a sweat. The spirits of the forefathers, the gubida, are present. It is their feast. Past and present are united.’

This passage from my diary describes a moment from a Garinagu ancestral ritual. Within the religious system of the Garinagu society rituals in which forefathers ‘participate’ are extremely important. A principal role during these rituals is taken in by the shaman. The Garinagu call this person buyai. A Garifuna shaman can be either a man or a woman. Shamanism is an essential part of the Garinagu’s religious system. As medium, the buyai makes sure that the ancestors come into contact with their offspring and vice versa during rituals. In this introduction, I will describe just one of these rituals, the dugu.

The dugu can be very intense and time-consuming. Executed in full splendor, it is the most expensive ancestral ritual performed by the Garinagu (Kerns 1989:173). During the dugu-ritual, the adugurahani, the participants call upon ancestors who have been dead for more than ten years. A dugu is performed because something troubling has happened within the family. According to the Garinagu’s religious system, such an incident van be an omen of misfortune, quite likely caused by the ancestors. The dugu serves as a ritual of reconciliation between the ancestors and their surviving relatives.

From my diary: ‘In the summer of 1989, a drama occurred in one of the Garifuna villages in Belize. A boy of about eight was playing in sea when he unsuspectingly stepped on a sting-ray. The sharp needle in the sting-rays tail pierced into an artery. In spite of ferocious attempts to save the boy’s life, he died.

All sorts of rumors quickly spread. The biological mother of the boy had immigrated to the United States a few years before the incident. The family members, who had taken the boy’s upbringing upon them, saw his death as a sign. The suspicion developed that one of the ancestors was not happy with the behavior of the biological mother. She supposedly paid too little attention to the well-being of her family. But, according to the rumors, it was especially her lack of respect for her ancestors that weighed heavily. The buyai from a nearby village was requested to make a diagnosis.’

First, the buyai checks to see if there is any witchery involved and also if it is possible that a drastic occurrence is a signal from an ancestor. Sickness or, as in the case of the boy, death can be caused by an ‘obeah man of woman’ (Gonzalez 1989:283).

In such a situation the buyai acts as a medium between the family and their ancestors. During a ceremony, the buyai uses special spirits, the hiuruha. A hiuruha is an ancestor who was a buyai himself during his time on earth, and now, thanks to a special bond with a living buyai, he is asked for advice.

The Performance of the Dugu

In the case mentioned above a short ceremony, the araíraguni, showed that there was a causal relationship between the mother’s assumed neglect of her ancestors and the boy’s death. Contact between the buyai and the ancestors quickly indicated that a gubida (ancestor) was pushing for a dugu and that witchery was out of the question.

During the araíraguni, the gubida also indicates which specific wishes must be kept in mind during the performance of the dugu and to what the participants must comply. The ancestor also determines the date and length of the dugu. By determining the latter, the ancestor also determines what the financial consequences are for the family. After all, the costs of the ritual rise along with the length, which can vary from one to three and sometimes even four lumangari. A lumangari stands for one day and the following night in which all sorts of ritual acts are executed. A lumangari lasts 24 hours.

If the araíraguni-ceremony has proved that an ancestor has requested a dugu, preparations for the ritual begin. For a large dugu, they can take up to a year. Members of the family must be informed that there is a dugu coming up. Those living in foreign countries must be told long enough beforehand, especially those living in the United States. They are often seen as family members with money, contrary to those from Honduras. In order to give enough people living in foreign countries the chance of come, the dugus are generally held in July, August or September.

Money, which is spent on poultry, pigs, rum and cassava, a buyai who is respected by all, drummers and the number of family members present determine the status of the dugu. Much of everything provides a high status, and little means it is an insignificant, small dugu with a low status.

Aside from informing the family, all sorts of other things are also taken care of during the preparations. The choice for both the buyai and the drummers must be clear. Arrangements are also made for the financial and/or material reimbursement for these people. The temple, dubuyaba, must be readied. The offers must be attained an/or prepared. The participants of a dugu-ritual usually begin with the preparations on Thursday afternoon. They bring the ereba (cassava bread), hiu (cassava beer), binu (rum) and many other attributes to the temple. The majority of these have a ritual function during the dugu. Four days later, on Monday morning the core ritual begins. It ends on the following Wednesday.

From my diary: ‘It is Thursday afternoon, August 16. At about 15 o’clock many people head for the dugu temple. An informant tells me that there will be drumming this afternoon. There are many people present outside of the temple. They are bringing all sorts of attributes into the temple, which are carefully stored, or in the case of the poultry, tied under the benches.

At about 16.30, the drummers begin to play. The rhythm is infectious. The sound is synchronous to the rhythm of the drummer’s harts. People dance and sing. The participants dance individually and shuffle forward. Interrupted by short pauses, the singing and dancing continues until 18.00. After that the activities in the temple stop. Early the next morning the fishermen go to the coral reefs along the coast. These islands are called cayes here. It is going to be an early start tomorrow morning.’

On Friday morning at about six o’clock, the next phase of the dugu starts. From this point on all of the participants stroll in to the temple. It all seems to be very relaxed. Friendly greetings take place and the latest news is exchanged. Some of them have spent the night in the temple. The buyai is busy sprinkling the inside of the temple with white rum. This facilitates the manifestation of the ancestors. It lets them know they are welcome.

The Drumming Begins

At about six-thirty, the drumming begins. The participants form a circle around the goods that are stored in the center of the temple. The buyai stands in the middle of the circle, sprinkling rum and blowing smoke over the goods, among which two outboard motors, a few paddles, plastic jerry cans with water and fuel, food, fishing attributes and a few baskets. These items are set aside for the boats leaving for the cayes sometime during the morning.

At about six-thirty, the drumming begins. The participants form a circle around the goods that are stored in the center of the temple. The buyai stands in the middle of the circle, sprinkling rum and blowing smoke over the goods, among which two outboard motors, a few paddles, plastic jerry cans with water and fuel, food, fishing attributes and a few baskets. These items are set aside for the boats leaving for the cayes sometime during the morning.

From my diary: ‘About thirty women and four men shuffle along in the circle in a very relaxed manner. First, the circle moves anti-clockwise. After a while the direction changes. While the participants move along to the beat of the drum, they sing and make jokes.

A woman standing outside of the circle falls into a trance. She pulls a man out of the circle that then dances with her. Many participants have a white ribbon in their hand with which they wave. I ask a few of the people standing nearby what the ribbon is for. The answers are evasive or they do not know. Later, someone tells me that the white ribbons calm the ancestors down.

The woman in trance and the man assisting her are now dancing inside the circle. The buyai takes two rattles, sisira, and begins to shake them. She stands in front of the drummers who stand up and follow her outside. Every participant takes something from the pile of attributes, which are to go along to the islands. The procession follows the buyai. The woman in trance dances and jumps in between everyone. At the beach, she shortly clamps herself to the buyai. The buyai walks over to the two boats and blows smoke from her cigar, the búe, over them. Next, she sprinkles rum over the boats and throws cassava beer out of a gourd over them.

A short commotion: there is not enough fuel for the outboard motors of both boats. Discussions follow. In the meantime, the drummers imperturbably provide the beat, until all of a sudden they stop.

Someone yells ‘let’s go’ and the boats are pushed out to sea. Those staying behind wave good-bye to the men and women going along for the journey. After a short time of silence, the drummers begin to play again. Those remaining go back to the temple. In the temple, a circle of dancers forms again and after a while another woman goes into a trance. The ancestors are present. Every time one of the women in trance comes close to leaving the temple, a great hilarity arises among the spectators. Especially the youth leave quickly if the threat becomes too great. The buyai stands in front of the drummers like a sort of conductor; she is extremely impressive.’

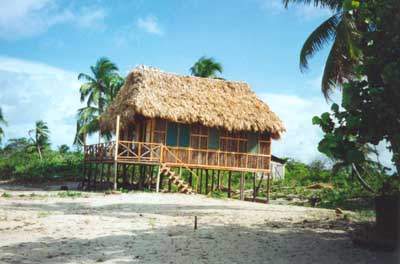

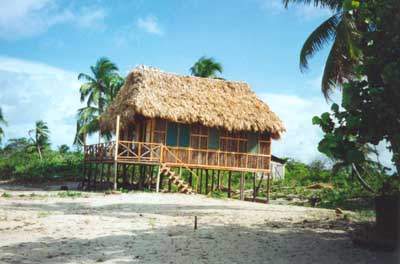

Those travelling to the coral islands have been appointed by the ancestors during the araíraguni. The group, which consists of a number of men and women, is led by a captain, the arünei. The participants of the trip are called adugaha. This word means: she or he who is to catch seafood for the dugu. The feminine participants go along to catch crabs. The men are for fish and shellfish (Macklin 1972:109). One of the participants of the fishing expedition was a fisherman who lived with his family near the thatched roof cabin in which I resided during my research. He told me that ‘this whole dugu business is no concern of mine’. In spite of this he found it a great honor to go along as arünei, captain.

During the journey, the fishermen are accompanied by a gubida. This ancestor makes sure that the fishermen return and that their baskets are filled with seafood (Macklin 1972:110). The crew of the fishing expedition from the case described above, left on Friday morning and returned to the village on Sunday afternoon. They used to be much more dependent on the weather. The trip to the reefs and islands was done by peddling and/or sailing. Today, the journey takes much less time due to the outboard motors. On Sunday afternoon, the buyai, the drummers and the participants gather together in the temple. The final preparations are made.

On Monday morning, the ritual in the temple begins with drumming, singing and dancing. The circle-dance is performed again. Some participants are dressed in orange. They belong to the next of kin of the ancestor who requested the dugu. The orange clothing is treated with an organic yellow-red dye. This dye comes from the fruit of the Bixa orellana and is called gusewe by the Garinagu. The buyai sprinkles in the temple. Elsewhere in the village, the fishermen and women who went to the islands push their boats into the water and head about a kilometer out to sea. They go up and down the coast a few times as if they are waiting for the right moment to moor. The boats are so decorated that they could be used for sailing. There are orange cloths hanging in the masts. In the meantime, the participants leave the temple. The buyai leads, followed by the drummers, the family members and finally the other participants.

Besides the participants of the dugu, there are remarkably many interested spectators present at the beach. The crowd on the beach cheers, sings and waves to the fishing boats. After the boats have been pulled up onto the beach, the baskets with fish, crab and shells are brought into the temple.

From my diary: ‘The temple is filled with participants. More and more people are holding a small bottle filled with rum in their hand. The bottle is closed by a white piece of paper. On this, messages have been written which are directed to an ancestor. During the ritual, these messages are offered to the ancestors. The bottles with their individual messages are gathered together at an especially reserved place in the temple. Others are holding a hen or a chicken. The poultry will be offered later. I get the impression that the participants are waiting for something. All of a sudden the buyai comes out from the back part of the temple. This part is separated from the rest by a wall and an opening with a cloth hanging in front of it. It is called the guli and functions as a sacred area. The buyai sprinkles rum on the walls and every now and again also on some of the participants. Some of the younger participants are clearly not enjoying this ritual act. After the sprinkling, the buyai blows smoke over all sorts of attributes. The drums, garawoun, are also ‘smoked on’. An informant tells me that the smoke from the cigar protects the participants from bad spirits. According to another informant, the buyai looks to see if everything is okay, or as he formulated it: ‘She checks it out’.

The mali or the amalihani, one of the ritual dances during the dugu is about to start. During this dance, in which sacred songs are sung, the ancestor comes through the floor and transforms him or herself into the body of one of the participants. When the mali begins, the three drummers are standing in the back of the temple in front of the guli. They stand next to each other facing the exit of the guli. One of the informants tells me that the buyai plunges her rattles in rum before stepping out of the guli. She does this to stimulate the transformation. After the buyai has left the guli, she stands in front of the drummers and sings out the name of the ancestor for whom this mali is meant. The drummers begin to beat out a rhythm. The participants are behind the buyai. They have a ribbon in their hand with which they wave forwards and backwards. A song is sung.

The Buyai slowly walks Forwards

The buyai slowly walks forwards and, in a way, forces the drummers to move backwards. The moment the drummers and the buyai are in the center of the temple, the buyai bends forward and positions the rattles just above the floor. The drummers follow her movements. All is quiet in the temple; you can only hear the beat of the drums.

Two of the three drummers point their instrument towards the drummer on the left. The beat is held just above the floor as if the four actors have made a pact. It seems as if they want to get something to come out of the floor. The four then repeat this act, but now this ritual act is projected on the space around the right drummer. The buyai accompanies the motions with her rattles; she is the conductor. During the actions the heads of the participants face downwards. Slowly the buyai stands up straight, followed by the drummers. There is a somewhat elderly man standing near the drummers and the buyai. During the ritual he stands there sweating and pouring drops of lemon juice into his throat. He turns out to be the head drummer. He das lost his voice, which makes things quite difficult, because he is the one who must announce the sacred songs. In spite of his handicap, he shouts out a sentence, which leads to the singing of a song by the participants.

During the mali, the buyai leads the drummers and the participants to positions in the temple that correspond with the four points of the compass. This ritual dance is repeated eight times every twenty-four hours during the dugu. Besides that, independent of the length of the dugu, one mali has to be dedicated to the temple. There is great excitement when someone is possessed by an ancestor during the mali. Even an outsider can feel the excitement.’

The rest of the day consists of ritual dancing alternated with time for resting. Some participants spend their rest-time in one of the hammocks, which are available in the temple. Others spend time with family members that they have not seen for some time or prepare food that will be eaten at a later stage.

In the evening, it is quite a lot busier than during the day. Many visitors have their usual business to deal with during the day, so that they can only participate actively in the evening.

During the dugu-ritual, much poultry is ritually slaughtered in the temple. The first session is on the day of the ceremonial welcome of the fishermen and women. In the evening, the poultry that are offered are collected. A stone is placed somewhere in the middle of the temple. Two drummers busy themselves with the birds. With a wide swing, the poultry’s heads are smashed on the stone one by one. It is almost logical that the rule of quantity determining the status of the dugu also counts for this ritual slaughtering.

A large part of the next day focuses on all sorts of offers. The members of the family organizing the dugu offer food cassava beer and rum to the ancestor who initiated the dugu. This day also offers a good opportunity to individual participants to treat other ancestors to food and drink. After a day of offering, there is much drumming and dancing in the evening and at night. Poultry are also ritually slaughtered on this day.

On the last day the ancestors are very present. In the above case, exhaustion was clearly getting to some of the participants. At this dugu, some of them brought more offers before sunrise on their own initiative. The mali is performed a few more times, and the buyai prepares a funsu. This is a cocktail made from eggs and rum.

Each person in the temple takes a small calabash of funsu to the gule, a small room at the back of the temple. Privately addressing a few words to the ancestors, each drinks the funsu, then returns to the main room’ (Kerns 1989:164).

After this there is more drumming

From my diary: ‘It seems as if the ancestors wish to liven up the feast by their presence just one more time. Many of the participants have been possessed by an ancestor or are dancing to the beat of the drums. During the day, more and more people disappear from the temple. The buyai and the next of kin of the ancestor, for whom the dugu was meant, stay behind. A number of closing rituals must still be performed. This means that a few of those involved are still present in the temple a few days after the dugu.’

The dugu is one of the rituals that honor ancestors that, together with a number of other rituals, forms the religious system of the Garinagu society. The notes from my diary cited above clearly portray that certain parts of the religious system are characteristic for the faith of Garinagu. In spite of these characteristic aspects, most of the Garinagu are ‘just plain’ Catholics. In this case, we can speak of syncretism.

Religion is a part of the cultural complex of an ethnic group. A religious climate provides much information on the position of ethnic groups. Religion is a social gauge, which shows if ethnic groups are permitted to express their own identity. Furthermore, the religious system can be an instrument used by ethnic groups to consolidate and/or strengthen their social position. Religious rituals also strengthen community and relational ties. People use rituals to make it known that they accept the common social and moral order of the group. This happens at the expense of one’s individual status. Douglas writes that rituals:

‘are either being used by one individual to coerce another in a particular social situation or by all members to express a common vision of society’ (1991:71).

In practice, it turns out that the deeper religious meaning of the rituals is more valuable to some participants than to others. Nonetheless, the rituals can be defined as social acts that are important to the ethnic group and the ethnic identity.

The Conception of the Soul

In the following section, the religious system of the Garinagu is described. After explaining the role of the Catholic Church within the Garifuna community, an overview of the pantheon is given. Next is a discourse on the conception of the soul and spirit held by the Garinagu. What happens when someone dies and what is the spirit of an ancestor? After this discussion, the specialists on this material have their say. Finally, I discuss a few rites de passage in the form of burial rituals and a number of other rituals that take place once a Garifuna has died. These last rituals are called ‘the cult of the dead’ by Foster (1987) and give a clear idea of the philosophy of life held by the Garinagu. In closing, section 4.3 is a reflection using the term collective fantasies.

The central question will be to what extent the present religious system of the Garinagu is a socially relevant cultural characteristic on which the identity of this ethnic group is based.

The Religious system

The Garinagu’s religious system has developed from a synthesis of various faiths. The most important of these are those of the Island Caribs, influences of African origin and Catholicism (Foster 1987). Even though there are elements during the various rituals honoring ancestors, such as the dugu, which symbolize the Catholic faith, there is a clear distance between the Catholic Church on the one hand, and the rituals in which ancestors appear on the other hand. Of old, Catholicism has played an important part in the process of Christianization of the Garinagu. Gonzalez (1988:82) writes that the French missionaries had converted about ten percent of the Black Caribs to Catholicism before they were deported from St. Vincent (1797). She adds that it is quite probable that the choice of these Black Caribs to let themselves be baptized was partly ‘a diplomatic move’ (1988:34).

In about 1800, the Garinagu landed in countries in Central America in which the Catholic missionaries had been converting for more than three centuries. During his travels through Central America in 1839, Stephens determined that most of the Garinagu in Punta Gorda in the south of Belize were Catholic:

‘like most of the other Indians of Central America, [they] received the doctrines of Christianity as presented to them by the priests and monks of Spain, and are, in all things, strict observers of the forms prescribed’ (1969:29).

It is quite likely that with his last phrase (‘strict observers of the forms’), Stephens subtly indicates his views of Catholicism. This does not make his prickling statement any less true, because it is quite possible that the Garinagu saw Catholicism as the religion of the colonial rulers. In spite of this, the liturgy of the Catholic Church was accepted as the formal religious system, while they informally held on to their cosmological ideas.

Today, 66.7% of the population of the Stann Creek District is Catholic. Just 5.3% indicate that they do not belong to a religious group (Central Statistical Office 1992). Besides the Catholic Church, the Anglican Church (6.5%) and a number of Protestant denominations are active in the Stann Creek District. These are doctrines such as the Pentecostal Church (4.5%), Methodists (4.5%), Adventists (2.9%), Baptists (2.2%) and Nazarenes (1.4%). In spite of the rise of these Protestant groups, Catholicism is still the most important official religious movement in Stann Creek District and the rest of the country.

In this context, the religious compilation of the Garifuna society in Stann Creek District is unremarkably consistent with the general picture of this region and the other districts in Belize. Foster (1984:11) notes that the participation in the Catholic rituals, including marriage, ties the Garinagu to the rest of society: it provides them with a sense of respect. These ideas guarantee the peaceful co-existence and create conditions for the Garinagu in which they can give their religion a specific content.

Most Garinagu seem like liberal Catholics with a balanced view on the function of the Church (see Foster 1984:11). In Dangriga and Hopkins, Catholic priests are treated with respect. This is also the case for representatives of other Christian institutions, including the old woman of the Jehovah’s Witnesses who promotes the Watchtower in Dangriga.

Priests are primarily seen as people who are professionals in performing rituals related to God. It is better to have such a person as a friend than as an enemy. Besides performing all sorts of religious rituals, priests also take on the part of advisor or ombudsman in social issues. On the other hand, issues that have more to do with internal relations in the family and/or the ethnic group are generally discussed with one’s own traditional specialists, such as the buyai or people with a certain status within the group.

There is a certain distance between the Catholic Church and the Garinagu. This is not enforced by the church, but by the Garinagu. As long as the church manages affairs useful to the Garifuna community a peaceful co-existence will continue to exist. The church is more a sort of strategic instrument then representative of an ideology. Foster describes this attitude towards the Catholic Church which is held by many Garinagu as follows: ‘religion is a matter of ritual obligation for the majority rather than a set of ideas to which they dedicate themselves’ (1984:11). The various Catholic holidays, such as All Saints’ Day, All Souls’ Day, Good Friday, Christmas et cetera, are celebrated with much devotion in Central America and Mexico. On the contrary, the Garinagu in Belize only celebrate Christmas with the usual festivities. The Catholic Churches in Dangriga and Hopkins are less conspicuous and much more sober than those in the neighboring countries of Mexico and Guatemala. The influence of the Anglican Church is expressed in the Belizean architecture.

Many of my informants in Dangriga and Hopkins put the influence of the Catholic Church in Belize into perspective. It is in no way comparable to the important social position that this Church takes in in the neighboring countries of Guatemala and Mexico and the rest of the countries in Central America. In Dangriga it was rumored that an important Belizean Catholic priest, very respected in the Central-American region, had gotten on the wrong track as far as his celibacy was concerned. A man in Dangriga commented the following on this: ‘Yeah man, life is a bitch and those guys are only human’. When questioned which social function the Church took in, an informant answered: ‘Well, usually they are good for something’. The answer that most put the Catholic Church into perspective was made by an old lady who confidentially told me during an interview that ‘death is not a decision of the Church, it’s in the hand of God’. This last comment concisely represents the relations. The Church is just an instrument; God has the power. What idea do the Garinagu have of God and are they familiar with supernatural phenomena?

The Pantheon

The Garinagu’s religious system, conform Christian doctrine, is based on the idea of one almighty God who they call Bungiu (derived from the French Bon Dieu). Most Garinagu assume that God is the Creator, next to God, the Virgin Mother and the Holy Child (Jesus) are also called upon in prayers and asked for help. Jesus is seen as the Son of God and of Virgin Mary. According to a buyai in Dangriga, God was the first forefather on earth (Foster 1984:11). The concept of one almighty God is clear and simple. Furthermore, God is on the top of the hierarchy of the Garifuna pantheon. Comments like: ‘It’s in God’s hands’ and ‘With God’s blessing’ characterize the resigned attitude of some believers in this truly intangible and powerful abstract phenomenon of the pantheon.

The monotheistic principle suggests that the Catholic dogma is completely accepted within the religious system of the Garinagu. However, the reality is different. The Catholic Church believes that people end up in heaven or hell after they die. The Garinagu do not have such a dualistic idea of heaven and hell as is preached in the Catholic Church. Foster notes the following on this:

‘However, though ‘Hell’ is rendered as mafiogati (place of devils), the concept of hell is quite foreign to the Garinagu, who believe that ‘what you do here, you pay for here’. For Garinagu, all souls, with the possible exception of murderers, travel to Sairi, the afterworld of luxuriant manioc gardens, at death’ (1984:11).

Man, at any rate the Garinagu, will not end up in hell after they die. One pays for sinful behavior during their earthly existence. In other words: there are supernatural powers on earth that influence the well-being of man and, in a sense, represent the component of hell on earth.

This way of thinking has quite a few consequences. The Garinagu have an almighty determining God and a heaven, the Sairi, where the soul goes after death. Next to the Bungiu, the pantheon has a category in which all dangerous and teasing supernatural beings are gathered together. At the head of this category is Satan or Lucifer (Foster 1984:12). Satan of Lucifer is called Uinani by the Garinagu (Foster 1984:12; Taylor 1951:104). Mafiogati is a place where these dangerous and teasing supernatural beings can reside. These beings are for instance able to make someone sick by taking the human body and its soul into its possession. They are also able to kill a person. Possession of a human body by a supernatural power is of a different order to the ancestors who possess the bodies of offspring, as in the introduction. The latter form has a therapeutic function, there where the ‘bad’ supernatural powers usually have a destructive function. This means that the Garifuna will have to take into account that life on earth can be hell. In the Garifuna pantheon, the supernatural beings on earth are represented by evil spirits. In spite of the name spirits, there is an essential difference between the evil spirits and the spirits of ancestors. Contrary to the spirits of ancestors, the first category has never been human. If is probable that they used to be gods who, with the rise of the monotheistic Catholicism, were given another position in the pantheon. Later in this section, it will become clear that the buyai, the ritual leader from the introduction, is, among others, a specialist in this material.

Not only the ancestral rituals, like the dugu, are an example of syncretism, but the Garifuna pantheon is also founded on this principle. This led to a hierarchical framework with one God at the top and under that three different complex categories of spirits in the religious system of the Garinagu. The most important category of spirits can be traced back to the supernatural world of the Island Caribs and/or Caribs on the mainland of South America. The other category of spirits consists of metaphysical phenomena that have been taken over from pantheons of other ethnic groups in Belize. The third category consists of spirits of ancestors.

The Spirits of the Island Caribs

Mafia is the Garifuna name for devil. The word is derived from the term Mapoya or Mapoia. This was a forest spirit or sylvan deity within the pantheon of the Island Caribs. Taylor (1951:103-4) notes that Mafia is both singular and plural. This means that there are more devils that reside in different places (Taylor 1951:104). Mafia are especially dangerous for pregnant or menstruating women. They appear in women’s dreams and try to seduce them (Taylor 1951:103). It is dangerous for men to have sexual contact with women who are possessed by Mafia. Foster (1984:12-3) states that the symbolism of the Mafia represents relations between men and women. The strength of the woman is expressed in her ability to reproduce. Her warmth symbolized by sexual stimulation (the seduction), giving birth to a child, breast milk, but also menstruation appeals to Mafia in their capacity as cold-blooded reptiles. The essence is that women are more difficult to check in some situations than men are. An insecure man will be the loser in such a situation and accept bad influences, which leads to calamities. For example, a woman getting too close to a newborn baby during her menstruation could lead to bleeding of the navel of the child (Foster 1984:12). A ‘strong’ man will make sure that this does not happen, because the ‘bad’ smell of menstruation blood indicates that a Mafia may be nearby.

The Uguriu is a greatly feared spirit. This being is also characterized as Beelzebub or as prince of the devil (Foster 1984:12-3). The term Uguriu is derived from the Island Carib word keleou, which means devourer. Uguriu is even more dangerous to man than Mafia. Analogue to Mafia, Uguriu has the power to take on the appearance of a reptile, for example, a snake, an iguana or a lizard (Foster 1984:13; Taylor 1951:105). Beelzebub is also capable of manifesting itself in other forms. Then he appears as a sea-crab, a dog, a chicken, an armadillo or a human.

Taylor (1951:105) focuses on the destructive influences that this devourer has in the house of its victims. This creature will devour the first-born of a family, and if the victims do not take measures, the same will happen to the rest of the children. Luckily, Uguriu can be manipulated, he just loves cassava beer and cassava bread. By placing these two products in a corner of the room at night, devouring of the children can be prevented. Uguriu can also possess a woman and let her dance as if she were crazy. Possession of a family’s house by this malicious spirit has many consequences for their fate. Because Uguriu is mainly linked to the house, it can mean that a family has to leave its shelter. In order to avoid this calamity, the residents of a house can take precautions. The best remedy is to bury three sea urchins in the ground within three steps of the threshold. This will keep the spirit out of the house. Taylor describes the Uguriu as a dangerous guest. Foster (1984:13) on the other hand, places Uguriu in the framework of the male-female relationship, as he did with Mafia. Women are also the potential victims of this spirit.

When Uguriu possesses a woman’s body, she is the ‘hostess’. It is also possible that Uguriu will devour her from inside and kill her. The sexual partners of these women can be infected and they await an awful death also coming from within (Foster 1984:13). This is contrary to the method used by Mafia, who will eventually attack a man in order to chase him away, but will never possess him.

Not unimportant is that one of the assumptions about Uguriu is that he was introduced by people from outside the ethnic group. Garifunawomen who carry Uguriu along with them are distrusted by their ethnic group. Their sexual partners, supposedly, too often belong to other ethnic groups (Foster 1984:13).

The Island Caribs believed that the world had an owner. This was symbolized by the night and was called Lakuelle Oubao (Foster 1984:12). The language of the Garifuna has the term Labureme Ubóu, which stands for ‘midnight, owner of world’ (E. Roy Cayetano 1993:148). Umeun is invisible to mankind and among children she causes hives, against which she has a terrible aversion (Taylor 1951:106).

A well-known appearance of a spirit in the Garifuna community is Agayuma. This is a river spirit. Foster (1984:12) writes that the word Agayuma is not a typical Island Carib word. Nonetheless, the Caribs on the South-American mainland have the word Akoyumo or Okoyumo, which means creek spirit. This spirit reveals itself as a woman and seduces men. The consequences of meeting Agayuma can be fatal. If the victim does not call upon a buyai for help, this person’s dreams will be an indication of his coming death.

Several spirits that were still mentioned several decades ago in the pantheon of the Garinagu have now disappeared. The first of these is Dibinaua. This was a sea spirit that primarily kept to the deep waters of the sea. Taylor (1951:106) comments that the concept of the Dibinaua was only expressed vaguely by his informants. Thirty years later, Forster (1984) does not mention this sea spirit. The People’s Garifuna Dictionary (E. Roy Cayetano 1993) does not contain the word Dibinaua. Besides Dibinaua, Taylor (1951:104) speaks of a forest spirit called Iauararugu. Taylor describes this phenomenon as ‘a large shaggy man’ (1951:104). Iauararugu is also not mentioned by Foster (1984) or The People’s Garifuna Dictionary (E. Roy Cayetano 1993).

The ‘Belizean’ Spirits

Besides these ‘Island Carib’ spirits, there are also spirits who originate from the Creole, Maya or Mestizo tradition. An example of such a spirit is La Sucia, ‘a very large woman with long, golden hair’ (Craig 1991:40). La Sucia comes from the Spanish word ‘sucio’, which means dirty, rude, indecent and infectious. According to tradition, she has, among others, been seen in Hopkins. Craig gives the following description of this spiritual phenomenon:

La Sucia is relatively harmless, but can be mischievous enough to frighten those with whom she comes in contact. Sometimes she will, like many of the other enchantresses, take the form of a man’s sweetheart in order to attract him. [Stories also exist about a La Llorana and Xtabai. The former primarily appears in the Orange Walk District, while the latter is more often associated with the Maya.] At times she will await victims on deserted roads; on moonlit nights, she baths by the riverside, lying in wait for some man, usually a drunk to pass by.

When she perceives a potential victim, she opens her gown, exposing her breasts, and laughs at the man. As he approaches her, she seductively draws him farther away from the road then suddenly disappears. The man who is tempted follows La Sucia, usually losing his way and falling asleep in exhaustion. Invariably he wakes up to find that he has been sleeping on a grave in the cemetery, and often he remains confused, suffering from fever and delusions about the bewitching woman in his encounter (Craig 1991:27-32).

Another ‘Belizean’ spirit is Duendu. He is a ninety centimeter long gnome. He wears a hat with a wide rim, has a mean face and a beard. Duendu is usually described as a vigorous old man who floats just above the ground when he walks. A whistling noise can be heard when Duendu is around (Craig 1991:27-32).

Various descriptions and stories exist on this gnome. One of these is that his feet are back-to-front. Duendu is the guardian angel of the animals and people in the forest. For instance, he helps people who are lost and when they are wounded he heals them. Duendu punishes hunters who kill more animals than they need. He also guards a treasure. Nonetheless, there are also countless stories in which Duendu is portrayed as a dangerous villain and a notorious tease. In the Stann Creek district, it is told that Duendu has no thumbs. As soon as he sees human thumbs he tries to pull them off. If you happen to meet this dwarf you should bury your thumbs in the palm of your hand. Duendu can also make children invisible and only a shaman can break the curse.

Burning candles and the Bible keep Duendu away. When confronted by him, making a cross is enough to scare him away.

Sometimes a bright light moving in circles appears at sea in the dark of the night. This phenomenon has a natural explanation, but nonetheless, is often explained as a supernatural phenomenon. The light, which sometimes develops into a ball of fire, can come dangerously close to the fishermen’s canoes. A fishing boot is sucked in by the picking up of the strong wind, and then sails around in circles, out of control. This hinder can be avoided by pointing two crossed knives in the direction of this phenomenon (Craig 1991:17, Taylor 1951:106). The Garinagu call this Faia Landia. It is supposedly a ghost ship still floating around along the coast of Belize. On this ship are the spirits of the first buccaneers who established themselves on the cayes near Belize City (Foster 1984:14). These freebooters, especially British in this region, are called Baymen in Belize. Today, they are often seen as founders of the British based Belize.

About the Soul, the Spirit, Death, Ancestors and Ghosts

According to Taylor (1951:102), the world soul is a term derived from Christianity. As far as I am concerned, this statement is of vital importance. It indicates that the Garifuna ideas on the existence of man are based on a combination of concepts. On the one hand, their ideas about mankind have developed along the lines of the Catholic Church. On the other hand, it will be shown that the elements of the portrayal of mankind as held on St. Vincent, are still very much alive. The Garifuna word for soul is áluma. This word is derived from the Spanish term for soul, namely ‘alma’. What makes the term soul so confusing is that it is grafted on the portrayal of man held by the Catholic Church whereas it is simply a part of the point of departure held by the Garinagu. Both concepts are similar in that they see the other aspect of mankind to be the body. In Garifuna, this is called úgubu. The Garifuna soul is called iuani. This means spirit of the heart and is derived from the Island Carib word ‘iouanni’ (Foster 1984:14). The essential difference between the term soul as used by the Catholic Church and the term spirit used by the Garinagu, lies in the tie to life on earth. Spirits, also those from the pantheon, are a fundamental part of life. Instead of a soul, the body contains a number of spirits that belong to the individual. One of those is the spirit of the heart, which is located in the heart organ.

This contains the rhythm of life, vitality, but also courage, indomitability and emotions. As long as one lives on earth, the iuani is bound to one’s body. Besides a spirit of the heart, everyone also has a spirit called afurugu (Foster 1984:12; Taylor 1951:102). This ‘spirit-duo’ can be seen as the double of one’s self-concept, but then in the form of a spirit. Afurugu appears in other people’s dreams. In other words: when I dream about someone, I am visited by his or her afurugu. Furthermore, a fever is seen as a sign that the afurugu is too loaded down (Taylor 1951:102). When a person all of a sudden gets the feeling that they have to go home because something is going on, they are inspired by afurugu (Taylor 1951:102). Afurugu is often compared to a personal guardian angel (Foster 1984:12).

In practice, the Garinagu do not deny the existence of the ‘Catholic ‘soul. A Garifuna will generally tell an outsider that the spirit of the heart and the soul are one and the same. When someone dies, the spirit of the heart (the soul) leaves the body to make the long journey to Sairi (Foster 1984:14). After this journey, the transformation from spirit of the heart to spirit to spirit of an ancestor is completed. Life, symbolized by the heartbeat, is replaced by the supernatural powers of the spirits of ancestors. Sairi, the world of the ancestors, is at the end of a long path. After the spirit of the heart has crossed a river, he or she is in front of the port to the hereafter Taylor (1951:107) notes that the spirits of the heart standing in front of the port before it is their time are chased away by a barking white dog. They have to go back to life. When the spirit of the deceased has passed through the port, he or she arrives in a lush garden filled with cassava plants and banana trees. Spirits of ancestors await the new arrival and welcome him or her with food and drink (Taylor 1951:107). Afurugu on the other hand, falls into a state of insecurity nine days after his or her ‘owner’s’ death (Taylor 1951:107). This constellation is because úgubu has been buried and iuani has joined the ancestor spirits in Sairi. Without its fountain of life, Afurugu flits through the dreams of loved ones still on earth for a while before passing into oblivion.

According to the Garinagu, the spirits of ancestors have two powers. The gubida and the ahari. These powers, which were together in the spirit of the heart, separate after arriving in Sairi. The spirits are not part of a closed system, so that these ancestral powers can continually present themselves to surviving relatives. The gubida is the negative power bound to earth, death and the grave (Foster 1981:3 and 1984:14). The gubida is impatient, dangerous and wishes confirmation by relatives through ritual acts. The ahari on the other hand, represents the positive power, the good. This ancestral influence is associated with creatures in the air like birds and butterflies. This ancestor spirit an also appear in dreams. Ahari warns and protects relatives (Foster 1981:3). Contrary to the gubida, the ahari is not demanding. A special ancestral spirit is hiuruha. Foster (1984:12) compares this spirit of a buyai to a Catholic saint. The term hiuruha is derived from the word ioulouca. This was the spirit of the rainbow in the pantheon of the Island Caribs. This ancestral spirit also resides in Sairi, but contrary to the ancestor spirits of ‘regular people’; it can be called upon by the buyai at any time. Today, a buyai normally can choose out of four or five hiuruhas. According to Taylor (1951:110), this number used to be much higher. This reduction could, on the one hand, point to the fact that knowledge of the various hiuruhas from the past is declining. On the other hand, it could be an effect of the rise of doctors, which has reduced the amount of work for buyais and made them focus more on psychic problems.

The last group of spirits of ancestors is the ufie, úfiaü or pantu, the Garifuna words for ghost. Because The Garinagu do have the concept of heaven, Sairi, but not of hell, some of the spirits of ancestors remain bound to earth. The Garinagu assume that man has to pay for his sinful thoughts and behavior during his stay on earth. ‘What you do here, you pay for here’ (Foster 1983:11). The consequence of this idea of life is that some lawbreakers are doomed to remain on earth. According to Foster (1984:11), murderers belong to this category. Their spirit of the heart will never make the journey to Sairi. Roaming over earth they present themselves in the form of ghosts. The annoying thing about these sinners is that they can take revenge on people they know or can be set to killing by someone who has the power over this category of ancestor spirits. Ufie betrays his presence by the smell of candle-grease (Taylor 1951:103). Thanks to this signal, a potential victim can bring himself into safety and, helped by a specialist, take countermeasures.

The conceptions of soul, spirit, death, ancestors and ghosts are an aspect of ethnicity that is based on the same, not so easily demonstrated grounds as the pantheon. Nonetheless, like the pantheon, it plays an important part in the imagery of the individual. Furthermore, for an ethnic group, these concepts are at the base of the collective ideas about life and death. They also make it clear to outsiders in which way an ethnic group interprets philosophical questions. The explanation contributes to the concretizing of abstractions and the support that they provide in situations in which the ethnic group is under pressure. This has to do with the fact that the explanation is of importance in regard to things like spirituality, dealing with grief and spiritual needs. In practice, it is especially these concepts, which are not so much in the limelight, that represent the instinctive and spiritual side of ethnicity.

Buyai’s, Obeahmen and Women and the World of Magic

In the summer of 1992, I was visited in Belize by a number of friends from Holland. I took them along to Hopkins. While my landlord, who was slowly becoming my best friend, a Garifuna from Dangriga, was using a machete to break open some coconuts, I heard an awful scream coming from the house which was about fifty meters away. Three women were standing at a distance and unmistakably swearing at us. What had upset these women so much?

There was a latrine close to the place where we were waiting for the refreshing content of the coconut offered to us by my friend. In Hopkins, a latrine usually is a hole in the sand with a fence around it. One of my Dutch friends thought the construction was so interesting that she took a photo of it. Something she should not have done. As was the case, there was a chicken skull hanging above the entrance to the latrine. It was hung there for the protection of the user of the latrine. After all, the user is in a vulnerable position. Dangerous spirits could attack at that moment. Therefore, the toilet must be protected against the influences of black magic or bad spirits. It is said that taking a picture of the specially prepared chicken skull causes its protective power to vanish.

Foster (1984) uses an example to describe how magic can be incorporated in the mutual relationships between family members. The example is about the power of a love potion, the wayaru (tempting powder). Women serve this to entice men. According to his source, men do not need this magical means, though some men use special prayers to win a woman over. The main characters in Foster’s example are a young man, his wife and his sister. All three of them lived in the United States, and the sister had gone back to Belize ‘seeking to obeah her brother’s wife, who had given him wayaru, as a result of which he no longer communicated with his kin and was unable to have sex with anyone except his wife’ (Foster 1984:14).

In these two examples, obeah (magic) is involved. The Garifuna asking for help can consult a buyai or an obeahman or woman for such things. The term obeah deserves further explanation. This magic power is experienced by the receiver as supernatural and can serve as a protection against all sorts of dangers.

It can also be used to hurt someone. In the strict sense of the word, a buyai and obeahmen and women use the power of magic. Or in other words obeah. This makes it even more remarkable that the Garinagu find that the obeah is not one of the skills of the buyai. Gonzalez (1989) categorized the work of a buyai and of obeahmen and women. The result of this is the following comparison:

The buyai can diagnose, heal, identify wrongdoers, perform love magic, trace lost items, can cause sickness and death, is always helped by a buyai spirit (hiuruha), executes public ceremonies, pleases evil spirits of death and of nature. The status of a buyai is ascribed (Gonzalez 1989:284). With the latter, Gonzalez points to the assumption that a buyai was born with his or her gift, but that he or she is not visited by spirits until the ninth year of age because the body is too weak before that time (Gonzalez 1989:288).

The obeahman or woman can make a diagnosis, heal, identify wrongdoers, perform love magic (better than the buyai), cause sickness or death, can use spirits, does not execute public ceremonies, acts with people ‘rather than non-human causative agents’ (Gonzalez 1989:285). The status of an obeahman or woman is acquired, with this she means that the power of magic can be learnt (Gonzalez 1989:285).

Furthermore, a buyai comes from the ethnic group, while an obeahman or woman can be a Creole, a Mestizo or someone from another ethnic group. In spite of the similarities in the above comparison, the magic acts of the buyai are qualified differently by the Garinagu than the capabilities of the obeahman or woman.

The difference in qualification is based on the goal set and on the ethnic descent. The acts of a buyai focus on directing the contact between forefathers and relatives on earth. The buyai also executes rituals meant to heal the Garifuna clients or to protect them from dangerous supernatural powers. The obeahman or woman is not an intermediate between ancestors and relatives. This person also performs ceremonies that can protect the person asking for help from supernatural powers. On the contrary, the obeahman or woman can also bring bad luck upon someone when someone else requests this. This distribution of tasks does not mean that a buyai will per definition refrain from specializing in obeah and practicing it, but it simply does not occur as often. The essential difference is that the role of the buyai lies in internal ethnic issues such as the contact between ancestors and surviving relatives whereas the obeahman or woman represents the dangers from outside the ethnic group. These can for instance be caused by a non-Garifuna putting a curse upon a Garifuna with the help of an obeahman or woman. In other words: the work of a buyai is a specific cultural and socially relevant characteristic of the Garinagu. The obeahmen or women are not specifically tied to one certain ethnic group. Therefore the work of this specialist lies more in the diffuse boundary area of the various ethnic groups, which is why it is not characterized as a cultural characteristic exclusive to the Garifuna society.

The buyai is a ‘gatekeeper’ within the ethnic group. This is a person who, on the one hand, knows all of the ins and outs of the heritage of the ethnic group and guards it. On the other hand, he or she propagates it in order to guarantee the continuity of the cultural aspects, which characterize the group, both inside and outside of the group. This also provides the ethnic group with recognizable forms with which they can express themselves. The buyai is an example of a ‘gatekeeper’ who is specialized in rituals. As a medium, the buyai maintains the relationship between the ancestors and surviving relatives. This shaman also protects clients within the ethnic group from disaster. The fact that the buyai has a central role in the traditional Garifuna rituals also means that he or she plays an important part in the term ethnicity. As this term is only concerned with the individual, but also with the image created of the group by the outside. In Belize a Garifuna is, among other, characterized by their shamanism. In practice, it does not make much difference if someone believes in the buyai or not. The characteristic is the more important here. For example, in Belmopan it was pointed out to me that Dangriga is the cultural center of the Garifuna culture, because the most influential buyai lived there.

Rituals after Death

Alongside their weekly services, the formal religious institutions also offer traditional Catholic or Protestant memorial services and burials. That what is done during these ceremonies is categorized under burial rituals in this discussion. These rites de passage follow the basic idea of funeral ceremonies held in other places in Latin America and the Caribbean. Along with these rites de passage the Garinagu have an informal system in which the ancestors have a central role. Foster (1987) typifies the concept that characterizes this system as ‘cult of the dead’. The rituals performed during cult of the dead have a therapeutic value. These ancestor rituals held a number of years after death contain a pattern that can be traced back to the traditional religious system of this ethnic group and are initiated by the buyai.

The Burial Rituals

Today, death in Dangriga is usually communicated by the cable television network. Before its arrival, the radio played a central part in this sort of thing. The mouth-to-mouth circuit in Hopkins and Dangriga also guarantees a rapid spread of knowledge of a tragic incident. When someone dies, the family keeps wake over the body. During this show of respect, acquaintances of the deceased and/or surviving relatives gather around the house where the body lies in state. The coffin with the neatly dressed bodily remains is placed on a table in the prettiest room of the house. At the head, the base and halfway down the coffin there are candleholders with a burning candle in them on both sides of the coffin. Another table serves as an altar on which there is a jug of holy water and pictures of various saints. There is always someone present in the room where the deceased lies in state up until the funeral. Visitors can literally say goodbye to the body of the dead person. Literally, because the Garinagu assume that the spirit of the ancestor can return to the world of the relatives at any time. The dugu, as described in the introduction, is an example of that. Outside people drink and eat.

Several women sing songs. If there is a musician among those present at the vigil, then the songs are accompanied by the guitar and/or the drum. Other people chat or murmur prayers. During a vigil in Dangriga at which I was present, some men consumed quite a lot of rum. As the evening went on, some of these gentlemen became quite boisterous. Not everyone appreciated this and it led to a long discussion on their behavior and the continuous decline of respect for the spirits of ancestors.

If the wake begins in the evening, it continues throughout the night until the morning. The focus of this day is the burial, the ábunahani. Family members and friends follow the procession to the church and the graveyard.

In Dangriga I witnessed such corteges. A number of processions were led by a jazz band. During one of the parades, the band played ‘ When the saints go marching in’. Gonzalez (1988:79) suspects that this innovation of the funeral ceremony comes from Garinagu from Honduras. Workers on contract from Honduras, who worked in New Orleans for a while, supposedly introduced this type of funeral ceremony into their communities. As the contact between the Garinagu from Honduras and Belize is almost boundary-less by the strong family ties, the jazz component of the funeral procession could have been passed on by family ties. On the other hand, the influence of the United States is so strong in Dangriga, that this renewal could have come straight from New Orleans.

Dangriga’s cemetery lies in the north of the city. There is nothing about this cemetery that indicates that the Garinagu have a specific burial culture. The cemetery in Hopkins gives one the same idea. This one lies somewhere out of the way, hidden between the foliage. Both do not give you the impression that the cemetery has an important role in the burial culture of the Garinagu. Just as in Dangriga, this field of deceased lies to the north of the city. Hopkins cemetery is small, sober and unremarkable. It even seemed quite sinister to me. My first impression was that this place was rarely visited. A number of wooden crosses marked where the deceased were buried. The amount of graves still recognizable was very low considering there were some 800 people living in the village. When counting the gravestones, I only got as far as seven. Both to the left and the right of the path, the crosses were placed so clearly that you could see in which direction the coffin lay. Presuming that the cross is placed at the head, the heads were facing to the west and the feet east. This positioning implies that when set upright, the coffin would be ‘facing’ the sea.