Abstract

Abstract

Concerns about population ageing apply to both developed and many developing countries and it has turned into a global issue. In the forthcoming decades the population ageing is likely to become one of the most important processes determining the future society characteristics and the direction of technological development. The present paper analyzes some aspects of the population ageing and its important consequences for particular societies and the whole world. Basing on this analysis, we can draw a conclusion that the future technological breakthrough is likely to take place in the 2030s (which we define as the final phase of the Cybernetic Revolution). In the 2020s – 2030s we will expect the upswing of the forthcoming sixth Kondratieff wave, which will introduce the sixth technological paradigm (system). All those revolutionary technological changes will be connected, first of all, with breakthroughs in medicine and related technologies. We also present our ideas about the financial instruments that can help to solve the problem of pension provision for an increasing elderly population in the developed countries. We think that a more purposeful use of pension funds’ assets together with an allocation (with necessary guarantees) of the latter into education and upgrading skills of young people in developing countries, perhaps, can partially solve the indicated problem in the developed states.

Keywords: the sixth Kondratieff wave, the sixth technological paradigm, Cybernetic Revolution, population ageing, world finance, pension funds, human capital, developed countries, developing countries.

Human capital is one of the most important drivers of economic development whose contribution to the growth of production and innovations is constantly

increasing. According to the OECD definition, human capital is ‘the knowledge, skills, competencies and attributes embodied in individuals that facilitate the creation of personal, social and economic well-being’ (OECD 2001: 18; see also Kapelyushnikov 2012: 6–7). Human capital is central to debates about welfare, education, health care, and retirement. However, we think that the latter (i.e., retirement) is less frequently debated than it should be. Meanwhile, in the West the rapid population ageing actually devaluates the national human capital in every developed country. There are certain grounds to expect that if the ageing generation is not substituted by a more numerous generation of young specialists, the share of the elderly population will increase and the human capital is likely to decline.

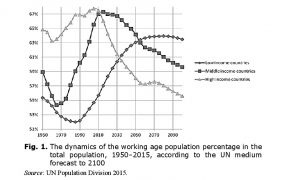

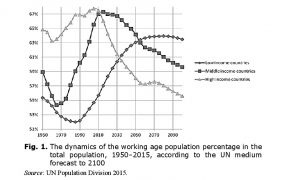

Thus, while the human capital as well as its contribution to the economic development is significantly larger in the developed countries than in the developing ones, the situation with demographic structure of human capital is different. The developing countries’ situation is significantly better at this point, and this can increasingly contribute to the economic competition between the First and Third worlds. We should also take into consideration the fact that the generation of highly educated pensioners in the developed states has increased the demands on society and they play a more active political role than the generation of uneducated ‘old men’ in the developing countries. While the West has apparently depleted its demographic dividend, many developing countries, in fact, are only in the process of its accumulation. And consequently, in this context they can get the most important advantage in the coming decades (see Fig. 1).

Thus, while the human capital as well as its contribution to the economic development is significantly larger in the developed countries than in the developing ones, the situation with demographic structure of human capital is different. The developing countries’ situation is significantly better at this point, and this can increasingly contribute to the economic competition between the First and Third worlds. We should also take into consideration the fact that the generation of highly educated pensioners in the developed states has increased the demands on society and they play a more active political role than the generation of uneducated ‘old men’ in the developing countries. While the West has apparently depleted its demographic dividend, many developing countries, in fact, are only in the process of its accumulation. And consequently, in this context they can get the most important advantage in the coming decades (see Fig. 1).

This also confirms the idea of growing convergence between the developed and developing countries that we adhere to, as the current differences in the

demographic structure and potentialities of the demographic dividend will contribute to the fact that at least in the next two decades the developing countries’ growth rates will be on average higher than those of the developed countries, although this process can proceed with certain interruptions (see Grinin 2013а, 2013b, 2013c, 2014, 2015; Korotayev and Khaltourina 2009; Khaltourina and Korotayev 2010; Korotayev, Khaltourina, Malkov et al. 2010; Korotayev and Bozhevol’nov 2010; Korotayev, Malkov et al. 2010; Malkov, Korotayev and Bozhevol’nov 2010; Malkov et al. 2010; Korotayev, Zinkina et al. 2011a; 2011b, 2012; Korotayev and de Munck 2013, 2014; Zinkina et al. 2014; Korotayev and Zinkina 2014; Korotayev, Goldstone, and Zinkina 2015; Grinin and Korotayev 2014a, 2014b, 2015а).

Problems of Population Ageing and Their Possible Solutions

Problems of Population Ageing and Their Possible Solutions

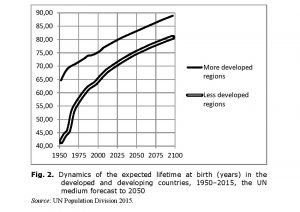

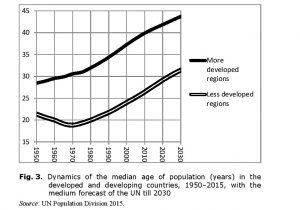

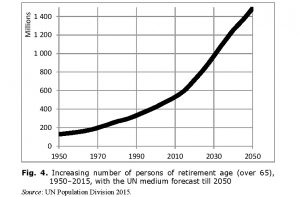

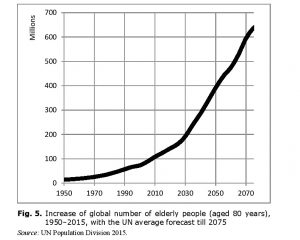

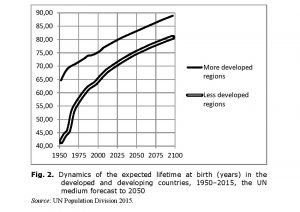

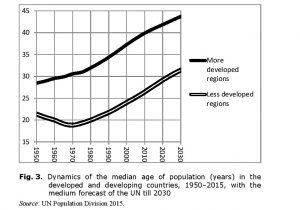

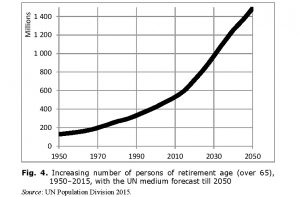

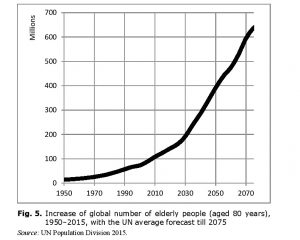

The population ageing (and an increasing number of disabled people) as well as the change in the population age structure (see Figs 2–5) alongside with forthcoming progress in medicine, innovation technologies, and increasing life expectancy in the developed countries will also bring great problems associated with a) the scarcity of labor resources; and b) problems of pension support for the older population.

In some countries they are rather acute already today, but they are to become much more pressing.

We would like to remind that if the median age of population of a given country equals, for example, 40 years, it means that half of the population of this country is younger than 40 years, and the other one is older.

We would like to remind that if the median age of population of a given country equals, for example, 40 years, it means that half of the population of this country is younger than 40 years, and the other one is older.

As is shown in Figure 4, a rapid global increase in the number of retirement-age persons is expected just in the next 20 years when their number will actually double within a small historical period, thus it will increase almost by 600 million and the total number will considerably exceed a billion.

However, a rapid acceleration will be observed in particular as regards the population of people aged 80 years or more. While by 2050 the number of persons of retirement age will approximately double, the number of elderly people aged 80 years or more will practically quadruple, and in comparison with 1950 their number by 2075 will increase almost by 50 times (see Fig. 5).

However, a rapid acceleration will be observed in particular as regards the population of people aged 80 years or more. While by 2050 the number of persons of retirement age will approximately double, the number of elderly people aged 80 years or more will practically quadruple, and in comparison with 1950 their number by 2075 will increase almost by 50 times (see Fig. 5).

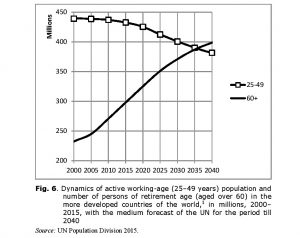

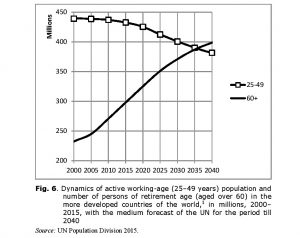

The First World countries will face particular difficulties in the next 20–30 years due to a rapid increase in the number of retirement-age people accompanied with an accelerated reduction of the active working age population, and in 20 years the number of the former will exceed the number of the latter (see Fig. 6).

The First World countries will face particular difficulties in the next 20–30 years due to a rapid increase in the number of retirement-age people accompanied with an accelerated reduction of the active working age population, and in 20 years the number of the former will exceed the number of the latter (see Fig. 6).

Incl. note i

As one can notice, the number of older people per a working age adult will increase. This is very likely to lead to the decline in living standards and to the increasing tension between generations.

One should keep in mind that the older population will form a major part of voters, thus making the politicians to follow their will. Besides, the highly

educated generation of pensioners in the advanced countries has certain demanding social requirements and they are more politically active than the generation of uneducated old people in the developing states. The transition to such a sort of gerontocracy also poses many other threats to a society and to its homogeneity because older people are more apt to conservatism and are less inclined to purchase expensive products, novelties and property, as well as to saving and this may reduce the focus on innovation and lead to considerable change of the contemporary economic model based on the expansion of consumerism. In particular, the population ageing in Japan is one of the reasons of the current deflationary trend (for more details see Grinin and Korotayev 2014c, 2015b).

In theoretical terms, it is possible to distinguish the following possible solutions for the specified problems (here we suppose that all those solutions will be applied, whereas none of them can solve the problem comprehensively):

1. To increase the number of immigrants in the developed countries. Still the opportunities of this pattern are to a large extent depleted and besides, it

leads to the erosion of the society’s major ethno-cultural basis (today we face serious challenges in this direction).

2. To raise the retirement age (together with active rehabilitation of the disabled people). Against the background of the forthcoming revolution in

medical and rehabilitating technologies this looks like an important (although insufficient) resource.

3. The development of labor-saving technologies, in particular robot techniques for nursing, as well as elder and disabled people care (for more details see Grinin L. E. and Grinin A. L. 2015а, 2015b; Grinin A. L. and Grinin L. E. 2015b). This will allow a partial reduction of expenses for care and different services,but it can hardly bring a complete solution of the problem of scarce resources.

4. Finally, the development of the financial system opens another path to the solution of problems with the pension system. The population ageing is directly related to the financial system not only within national systems, but within the global financial system as well. Due to the increasing number of retirees the pension savings have become not simply important, but essential to a certain extent.

Besides, we should note that, on the one hand, today pension and other social funds are not isolated only within a framework of national system, but make an important component of the world finance in the long run. On the other hand, stable pension system substantially depends on the stable and efficient global financial system, even to a greater extent than on the national one.

In the present article we will consider the second and the third directions in the solution of the problem of global population ageing which are closely interconnected, and then we will pass to consideration of the fourth (financial) one.

Global Population Ageing and the Sixth Technological Paradigm

The Cybernetic Revolution is a great breakthrough from industrial production to production and services based on the operation of self-regulating systems.

Its initial phase dates back to the 1950–1990s. The breakthroughs occurred in the spheres of automation, energy production, synthetic materials, space technologies, exploration of space and sea, agriculture, and especially in the development of electronic control facilities, communication and information. We assume that the final phase will begin in the nearest decades, that is in the 2030s or a bit later, and will last until the 2070s.

We denote the initial phase of the Cybernetic Revolution as a scientific-information one, and the final – as a phase of self-regulating systems. So now we are in its modernization phase which will probably last until the 2030s.

This intermediate phase is a period of rapid diffusion and improvement of the innovations made at the previous phase (e.g., computers, internet, cell phones, etc.). The technological and social conditions are also prepared for the future breakthrough. We suppose that the final phase of the Cybernetic Revolution will lead to the emergence of many various self-regulating systems (for more detail see Grinin 2006, 2009, 2012, 2013d; Grinin A. L. and Grinin L. E. 2013, 2015a, 2015c; Grinin L. E. and Grinin A. L. 2015a, 2015c).

So we expect the beginning of the final phase of the Cybernetic revolution in the 2030s and 2040s. We assume that this technological breakthrough at first

will be connected with a breakthrough in the field of new medical (and related to them) technologies. Thus, the increasing process of population ageing (as we will show further) will become one of the most important reasons of development of the final phase of Cybernetic Revolution.

This phase, according to our forecasts, will be imposed on the sixth Kondratieff wave (which will probably last from the 2020s to the 2060s). Therefore,

the sixth technological paradigm (known also as technological system or style)[ii] will be connected with major transformations of the Cybernetic Revolution. We consider the widespread ideas that the basis of the sixth technological paradigm will be formed by the NBIC technologies (or NBIC-convergence), which are nano-bio-information and cognitive technologies (see Lynch 2004; Dator 2006;Pride and Korotayev 2008; Akaev 2010, 2011; see also Fukuyama 2002)[iii] to be only partially true.

We believe that the basis of the sixth technological paradigm will be significantly wider. In general medicine, bio- and nanotechnologies, robotics,

information and cognitive technologies will become the leading technological trends. They will create a complex system of self-regulated production.

We could define this complex as MBNRIC-technologies, by the first letters of the listed technological directions. Thus, it makes sense to speak about medicine as the central element of the new technological system (see also Nefiodow 1996; Nefiodow L. and Nefiodow S. 2014). Medicine more than any other field has unique opportunities for merging all these new technologies into a single system. Besides, a number of demographic and economic reasons explain why this is precisely medicine that should start the transition to the new technological paradigm.

This will be supported by particularly advantageous situation developing by 2030 in economy, demography, culture, a standard of living, etc. that will define a huge need for scientific and technological breakthrough. By advantageous situation, we do not mean that everything will be perfectly good in economy; just on the contrary, everything will be not as good as it could be. Advantageous conditions will be created because reserves and resources for continuation of previous trends will be exhausted, and at the same time the requirements of currently developed and developing societies will increase. Consequently, one will search for new developmental patterns.

Let us describe the background.

– By this time the problem of population ageing will show up to the full (for more detail see the previous section). Moreover, this issue can turn simply

fatal for democracies in developed countries (because the main electorate will be represented by elderly cohorts, and also the generation gap will increase [see also Fukuyama 2002]). In addition, the problem of population ageing will become more acute in a number of developing countries, for example, in China

and even in India to a certain extent (about ageing in Asia see contributions of Park and Shin to this volume).

– The pension payments will become an urgent problem (as the number of retirees per an employee will increase) and at the same time the scarcity of labor

resources will increase, which is already felt rather strongly in a number of countries including Russia (for more detail see Grinin and Korotayev 2015c,

2010; Korotayev and Bozhevolnov 2012; Korotayev, Khaltourina, and Bozhevol’nov 2011; Arkhangelsky et al. 2014; Korotayev et al. 2015). Thus, the problem of scarce labor and pension contributions will have to be solved in such a way that people physically could work for ten, fifteen and even more years (certainly here we can also face a number of social problems). This also implies the disabled people’s adaptation for their fuller involvement into labor

process due to new technical means and achievements in medicine (for more detail see Grinin L. E. and Grinin A. L. 2015b).[iv]

– Simultaneously, by this time, the birth rate in many developing countries will significantly drop (for example, such developing countries as China, Iran, or Thailand already experience below-replacement fertility). Therefore, the respective governments will begin (and some of them have already started) worrying generally not about the problem of restriction of population growth, but about promotion of population growth and population health.

– A huge volume of medical services in the world makes about 10 % of the GDP (and in a number of developed countries it makes more than 10 %, as, for

example, in the USA – 17 % [calculated on the basis of World Bank 2015 data]). The population ageing will make these volumes grow rather significantly.[v]

– The development in the Third World countries leads to the growth of a vast stratum of middle class, while poverty and illiteracy are reduced. As a result, the emphasis of these countries’ efforts will shift from the elimination of unbearable living conditions to improvement of the quality of life, health care, etc. Thus, large opportunities open up for the development of medicine which will get additional funds.

So by the 2030s, the number of middle-aged and elderly people will increase; economy will desperately need additional labor resources while the

state will be interested in increasing the working ability of elderly people, whereas the population of wealthy and educated people will grow in a rather

significant way. In other words, the unique conditions for the stimulation of business, science and the state to make a breakthrough in the field of medicine will emerge, and just these unique conditions are necessary to start the innovative phase of revolution!

It is extremely important to note that enormous financial resources will be accumulated for the technological breakthrough, such as: the pension money whose volume will increase at high rates; spending of governments on medical and social needs; growing expenses of the ageing population on supporting health, and also on health of growing world middle-class. All this can provide initial large investments,high investment appeal of respective venture projects and long-term high demand for innovative products, that is, a full set of favorable conditions for a powerful technological breakthrough will become available.

In the context of population ageing problem we will consider some characteristics of the global financial system.

The Crisis and the Characteristics of the Financial System

The 2008 crisis and subsequent years aggravated both financial and economic,as well as some global social problems. One of the most important problems

among them is the problem of secure social guarantees for rapid ageing population of the World System core. In each country the security of these guarantees is connected with stability of the world financial system.

Let us recollect some important reasons of the global financial economic crisis:

– Random and extremely rapid development of new financial centers and financial flows;

– Non-transparency of many financial instruments, which led to the actual concealment of risks and their global underestimation;

– An excessive level of public debt in many developed and developing countries combined with ineffective use of credits.

They often also say that modern financial technologies are fundamentally deleterious and only bring the world economy into various troubles and that

they are only beneficial to the financiers and speculators. Thus, it would hardly be an exaggeration to maintain that the global crisis, as well as other events, has demonstrated, in an especially salient way, the necessity for major changes in the regulation of international economic activities and movements of world financial flows.

Nevertheless, we believe that it is reasonable to speak not only about the negative role of the world financial flows. On the whole, new financial technologies decrease the risks in a rather effective way and expand opportunities to attract and accumulate enormous capitals, involve actors, and penetrate markets.

The positive effects of the new financial technologies consist in the following:

1. A powerful expansion of the range of financial instruments and products, which leads to the expanding opportunities to choose the most convenient

financial instrument.

2. The standardization of financial instruments and products provides a considerable time-saving for those who use financial instruments; it makes it

possible to purchase financial securities without a detailed analysis of particular stocks; this leads to an increase in the number of participants by an order of magnitude.

3. The institutionalization of the ways to minimize individual risks. Some financial innovations and new regulations help to minimize both the individual

risks of unfulfilled deals and also of bankruptcies in the framework of certain stock markets.

4. The increase in the number of participants and centers for the trade of financial instruments. Modern financial instruments have made it possible to

include a great number of people via various special programs, mediators, and structures.

We also suppose that new financial technologies and modern financial sector have also got such important positive functions as the ‘insurance’ of social

guaranties at the global scale. The matter is that the rejection of the gold standard resulted in the movement of the function of the protection of savings from an ‘independent’ guarantor (i.e., precious metals) to the state. However, there was no state left for the capital owners to entirely rely on as on a perfectly secure guarantor.

The absence of secure guarantees is especially important in terms of the ways to preserve pension and other social funds.

The sharp increase in the quantity of capitals, the necessity to preserve them from inflation and to find their profitable application objectively pushed the financial market actors to look for new forms of financial activities. Generally, the faster are the movements and transformations of financial objects, the better is the preservation of capitals.

Another important point is the distribution of risks at the global scale. We observe growing opportunities to distribute risks among a larger number of participants and countries, to transform a relatively small number of initial financial objects into a very large number of financial products. This makes it possible to achieve the maximum diversification by allowing people to choose convenient forms of financial products and to change them whenever necessary.

The next point is the growth of financial specialization (including various forms of deposit insurance) that supports diversification and the possibilities for expansion.

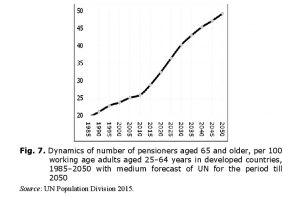

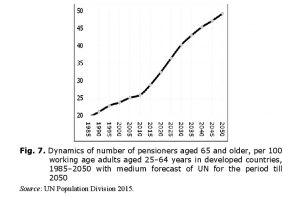

In 2010, there was one pensioner per four working-age adults, whereas in 2025, according to the forecasts of the UN Population Division there will be

In 2010, there was one pensioner per four working-age adults, whereas in 2025, according to the forecasts of the UN Population Division there will be

less than three working-age adults per a pensioner in the developed countries, and there exist even more pessimistic forecasts (see Fig. 7). Who will fill the pension funds in the future? Who will fulfill the social obligations with respect to hundreds of millions of elderly voters?

Here one should take into account that most pension funds are concentrated not in the state pension funds, but in thousands of private (non-state) pension funds (OECD 2014b) that rather actively search for the most secure and profitable investments. The amounts of money concentrated in pension and other funds are enormous: dozens trillion US dollars (see, e.g., Shtefan 2008; OECD 2014a; 2014b, 2015; see also Fig. 8).

In 2012, the accumulations in pension funds of the OECD countries amounted 77.1 % of their GDP, but in 2013 this indicator grew to 84.2 % (OECD 2014b: 7).

In 2012, the accumulations in pension funds of the OECD countries amounted 77.1 % of their GDP, but in 2013 this indicator grew to 84.2 % (OECD 2014b: 7).

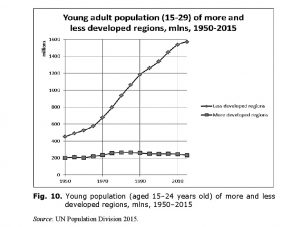

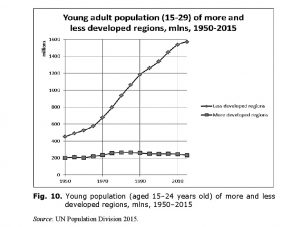

Meanwhile, in the developing countries we observe a huge number of young adults; and it is extremely difficult to provide all of them with jobs and education (see Fig. 10).

It is difficult or even impossible to solve this task without active integration of the peripheral economies into the World System economy as well as without diffusion of capitals and technologies from the World System core; in its turn, such integration cannot be achieved without the development of the world financial system. The situation favors this in some respects because the number of pensioners in the developing countries is still relatively small, the social obligations with respect to them are relatively few, and only after a significant period of time the problem of the pensioners’ support will become acute in those countries.

It is difficult or even impossible to solve this task without active integration of the peripheral economies into the World System economy as well as without diffusion of capitals and technologies from the World System core; in its turn, such integration cannot be achieved without the development of the world financial system. The situation favors this in some respects because the number of pensioners in the developing countries is still relatively small, the social obligations with respect to them are relatively few, and only after a significant period of time the problem of the pensioners’ support will become acute in those countries.

Consequently, the point is to involve pension and other social funds in boosting the developing countries’ economies more actively.[vi] It will assist the latter to provide jobs and education for the young people at present and will multiply the funds in the future. In this case under certain agreements between developed and developing countries it will be possible to achieve a situation when the rising economies will allocate some assets to support the growing layer of older people in the West, the latter will act as a rentier in this case (recently Joseph Stiglitz has expressed similar ideas [Stiglitz 2015]).

Then, there will be no need in the direct migration of millions of young people from the Third World to the First one; thus, there could emerge a sort of

solidarity between different generations of the global world. Of course, such a system will demand considerable measures with respect to security and reliability of such investments. But at the same time, it would provide a certain convergence of different countries’ interests.

Thus, we may say that:

– The participation of pension and insurance funds in financial operations leads to the globalization of the social sphere.

– The countries poor in capital, but with large cohorts of young population, are involved more and more in a very important (though not quite apparent)

process of supporting the elderly population in the West through the unification of the world financial system, its standardization, and the search for the ways to make it more fair and socially oriented.

– Modern financial assets and flows became global and international; a considerable amount of money circulates within this system (though, of course,

not all its participants make equal profits).

– At the same time, one should realize that a considerable part of the circulating sums is the money from social funds (in particular from the pension

ones) and their loss can lead to disasters with such consequences that are very difficult to predict.

– Safe management of the global capital (in addition to its obvious economic and social merits) assures the safe future for the elderly and those who

needs social protection.

– Therefore, the problem of institutional support of financial globalization becomes more and more important.

Let us indicate some key points which clarify the opportunities and difficulties of the suggested scheme; besides, let us outline some of the most important institutional decisions which could help this scheme to function in practice.

First. The pension monies play a certain role in the financial system and depend on well-being and normal functioning of the latter. Money from pension funds is still one of the major systemic components of national and world financial systems. Actually, this means that these are just pension funds that remain one of the leading traders buying government bonds, and also actively buying shares and other securities at stock markets. While the conservative investment policy of pension funds is quite reasonable in general, at the same time it makes them as well as many other subsystems of the financial system highly dependent on the manipulations of the Central Bank, rating agencies and other actors. Particularly, the income of pension funds has considerably decreased in recent years due to deflationary tendencies and low rates on the government debt securities (as the government pays low interests rates to pension funds on the most reliable debt bonds).

Second. Mounting crisis phenomena in financial system are able to radically undermine the well-being of pension funds. The latter have actively invested in securities; therefore, the cost of their assets largely depends on the price of securities. On the one hand, the governmental authorities and exchange players wish to manipulate this cost and its artificial high price (e.g., the so-called buyback transaction of the securities by firms), and on the other hand, in case of crisis the assets’ slump can be quite serious. For example, while in 2007 the asset value of US pension funds amounted to 78.0 % of the American GDP, during the crisis in 2008 it dropped to 59.6 % of GDP. The situation returned to pre-crisis level only in 2013 (OECD 2015: Funded Pensions Indicators: Occupational pension funds’ assets as a per cent of GDP); in other words, pension contributions have become entirely dependent on the economic situation. Therefore, we need some mechanisms of preserving accumulations, including the opportunity to lean on the world financial system.

Third. As we have said earlier, today the secure preservation of the value of accumulated funds depends on the speed of their circulation. However, finances do not exist by themselves, they can hardly break from the production base for a long time and has to rely on real production (the increasing separation of the financial system from production is one of the main problems of the current situation which is largely supported by the monetary doctrine). Thus, we face the necessity of driving the finances (and pension money) beyond national borders. Especially at present, since the production is rather actively moved to the developing countries. Therefore, no wonder that many pension funds invest into emerging markets to increase their income (OECD 2014a: 15). Only few funds do not invest in foreign assets, while some, on the contrary, invest a large amount of their capital abroad (Ibid.). Certainly, the foreign investments do not always imply investments into developing countries. Nevertheless, some investments are made, and thus, the proposed scheme already functions in a certain way. But we can face several serious problems.

First, this is most often ‘short’, in fact, speculative money, whereas generally these are long-term investments that can serve a real source of economic development and income.

Second, this money is almost the first to leave the emerging markets because of their volatility (not least connected with the policy of FRS and ECB) and fully justified conservatism of pension funds; and this also increases the volatility.

Third, the emerging markets certainly offer less guarantees than the developed ones, and therefore, the cautiousness of the funds is fully justified.

Fourth. For an effective functioning of the proposed scheme some highlevel agreements are necessary. Here various forms could be used, for example, investment of money of pension funds in the assets of such largest international financial institutions, as the IMF, WB, ADB, etc. These investments would be non-voting, but the money would be much securer there, and special obligations could guarantee that these funds would be allocated to increase the level

of education and qualification of young people in the developing countries.

It would be quite reasonable to develop some global organizations for the sake of cooperation between pension and other funds, as well as establishing

common insurance funds that will make it possible to support countries in case of a crisis. One could establish an International Pension Fund or something of the kind which would realize financial transfers so that the assets of the ‘older’ population of some countries could help to raise the economy in the countries with ‘young’ population and to accumulate funds for donor countries for the future. Some specific arrangements between countries with certain guarantees for safety of funds would seem rather appropriate. In brief, there could be many options. But the main problem is that despite the fast population ageing, the versions of global solution for the problem are poorly considered.

The Russian philosopher, Alexander Zinoviev, deported to Germany in the 1970s, quite accurately described the Western society as a society of monetary

totalitarianism (Zinoviev 2003) where the mechanism, realizing and preserving it, had reached enormous scales and had become one of the most important pillars of the society. This mechanism had formed in the period of the gold standard and after its cancellation the scale of financial economy had grown tremendously, having spread all over the world. In fact, a new huge sector of financial services has emerged which in some countries amounts to 25–30 % of their GDP. But the importance of this sector will increase in almost all countries, and will also involve their most important social functions.

Hence, the issue of the institutional support of the financial globalization becomes more and more important. We can speak about an extraordinary importance of the reliability and controllability of this system. Its changes should include the increasing coordination between governments and unified international legislation which regulates financial activities and movements. Besides, one should take into account that today the developed countries generally get more benefits from this system and constantly use it to solve their national issues (thus, affecting the whole world) and also they willingly use it as a means to impact other countries’ economies.

We suppose that important guarantees for the future Western pensioners will consist in the development pattern of the global economy which should

transform into a single organism. Thus, the global financial system would be come strong but will be used neither to get the developing countries under control nor as a means to collapse the Third World countries’ economies, nor as a means of unwarranted sanctions and suppression of societies and regimes

which the West considers uneasy. There should occur some transformations in the global financial system that would take into account the growing economies’ interests and thus allow the developing countries to more actively use the social funds accumulated by the West. And at the same time, this will prevent certain governments from expropriating the invested funds.

Actually, the world needs a new system of financial-economic regulation at the global scale.

This research has been supported by the Russian Foundation for the Humanities (Project № 14-02-00330).

Previously published in: HISTORY & MATHEMATICS: Political Demography & Global Ageing. Bibliography: Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House, 2015. – 176 pp. Edited by: Jack A. Goldstone, Leonid E. Grinin, and Andrey V. Korotayev. ISBN 978-5-7057-4670-5

NOTES

[i] More developed countries/regions according to the UN classification.

[ii] Within this approach every Kondratieff wave is associated with a certain leading sector (or leading sectors), technological system or technological style (see Korotayev and Grinin 2012; Perez 2002, 2010). For example, the third Kondratieff wave is sometimes characterized as ‘the age of steel, electricity, and heavy engineering. The fourth wave takes in the age of oil, the automobile and mass production. Finally, the current fifth wave is described as the age of information and telecommunications’ (Papenhausen 2008: 789).

[iii] There are also researchers (Jotterand 2008) who consider GRAIN (Genomics, Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, Nanotechnology) to be the leading set of the technological directions in the future.

[iv] About the influence of ageing on growth rates see the papers of Goldstone and Park and Shin in this volume.

[v] Some studies find that health care costs of patients aged 75–84 years are almost twice as large as the costs of 65–74 years old patients; and the expenses on patients of the 85+ age group increase by more than three times in comparison with the latter (Alemayehu and Warner 2004; Fuchs 1998). The cost of home care and short-term stay in the hospital also to a large degree depends on the patients’ age (Liang et al. 1996).

[vi] It is worth noting that they already participate in this process. Thus, in the large private retirement funds surveyed in 2014 by OECD staff, an average of 36.6 % of all capital were invested abroad (OECD 2014a: 15), whereas more than a half of the surveyed large pension funds invested a part

of their capitals in developing economies (ОЕСD 2014а: 13, 31, 43).

References

Akaev A. A. 2010. Modern Financial and Economic Crisis in the Light of the Theory of the Economy’s Innovative and Technological Development of Economy and Controlling of Innovative Process. System Monitoring of Global and Regional Development / Ed. by D. A. Khaltourina, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 230–258. Moscow: LIBROKOM. In Russian (Акаев А. А. Современный финансово-экономический кризис в свете теории инновационно-технологического развития экономики и управления инновационным процессом. Системный мониторинг глобального и регионального развития / Ред. Д. А. Халтурина, А. В. Коротаев, с. 230–258. М.: ЛИБРОКОМ/URSS).

Akaev A. A. 2011. Mathematical Bases of Kondratieff – Schumpeter’s Innovative and Cyclic Theory of Economic Development. Vestnik instituta ekonomiki RAN 2: 39–60. In Russian (Акаев А. А. Математические основы инновационно-циклической теории экономического развития Кондратьева – Шумпетера. Вестник инсти-тута экономики РАН 2: 39–60).

Alemayehu B., and Warner K. E. 2004. The Lifetime Distribution of Health Care Costs. Health Services Research 39(3) June: 627–642.

Arkhangelsky V. N., Bozhevolnov J. V., Goldstone J., Zverevа N. V., Zinkina J. V., Korotayev A. V., Malkov A. S., Rybalchenko S. I., Ryazantsev S. V., Steck P., Khaltourina D. A., Shulgin S. G., and Yuryev Y. L. 2014. In 10 Years It Will Be Late. Population Policy of the Russian Federation: Challenges and Scenarios. Moscow: Institut nauchno-obschestvennoy ekspertizy; A RANKhiGS pri Presidente RF; Rabochaya gruppa ‘Semeynaya politika i detstvo’ Ekspertnogo soveta pri Pravitel’stve RF. In Russian (Архангельский В. Н., Божевольнов Ю. В., Голдстоун Д., Зверева Н. В., Зинькина Ю. В., Коротаев А. В., Малков А. С., Рыбальченко С. И., Рязанцев С. В., Стек Ф., Халтурина Д. А., Шульгин С. Г., Юрьев Е. Л. Через 10 лет будет поздно. Демографическая политика Российской Федерации: вы-зовы и сценарии. М.: Институт научно-общественной экспертизы; РАНХиГС при Президенте РФ; Рабочая группа «Семейная политика и детство» Экспертного совета при Правительстве РФ).

Dator J. 2006. Alternative Futures for K-Waves. Kondratieff Waves, Warfare and World Security / Ed. by T. C. Devezas, pр. 311–317. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Fuchs V. 1998. Provide, Provide: The Economics of Aging. NBER Working Paper no. 6642. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Fukuyama F. 2002. Our Post-human Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Grinin L. E. 2006. Productive Forces and Historical Process. 3rd ed. Moscow: KomKniga. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Производительные силы и исторический процесс. Изд. 3-е. М.: КомКнига).

Grinin L. E. 2009. State and Historical Process: Political Cut of Historical Process. 2nd ed., rev. and add. Moscow: LIBROKOM. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Государство и исторический процесс: Политический срез исторического процесса. Изд. 2-е, испр. и доп. М.: ЛИБРОКОМ).

Grinin L. E. 2012. Kondratieff Waves, Technological Ways and Theory of Production Revolutions. Kondratieff Waves: Aspects and Perspectives / Ed. by A. A. Akaev,R. S. Greenberg, L. E. Grinin, A. V. Korotayev, and S. Yu. Malkov, pp. 222–262. Volgograd: Uchitel. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Кондратьевские волны, технологи-ческие уклады и теория производственных революций. Кондратьевские волны: аспекты и перспективы / Отв. ред. А. А. Акаев, Р. С. Гринберг, Л. Е. Гринин, А. В. Коротаев, С. Ю. Малков, с. 222–262. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L. E. 2013a. Globalization Shuffles the Cards (Where does the Global Economic and Political Balance of the World Move?). Vek globalizatsii 2: 63–78. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Глобализация тасует карты (Куда сдвигается глобальный экономико-политический баланс мира). Век глобализации 2: 63–78).

Grinin L. E. 2013b. ‘The Dragon’ and ‘the Tiger’: Models of Development and Perspectives. Istoricheskaya psikhologia i sotsiologia istorii 1: 111–133. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. «Дракон» и «тигр»: модели развития и перспективы. Историческая психология и социология истории 1: 111–133).

Grinin L. E. 2013c. Models of Development of China and India. Gosudarstvennaya sluzhba 2: 87–90. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Модели развития Китая и Индии.Государственная служба 2: 87–90).

Grinin L. E. 2013d. Dynamics of Kondratieff Waves in the Light of Theory of Production Revolutions. Kondratieff Waves: Diversity of Views / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, A. V. Korotayev, and S. Yu. Malkov, pp. 31–83. Volgograd: Uchitel. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е.Динамика кондратьевских волн в свете теории производственных революций. Кондратьевские волны: палитра взглядов / Отв. ред. Л. Е. Гринин, А. В. Коротаев, С. Ю. Малков, с. 31–83. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L. E. 2014. India and China: Models of Development and Perspectives in the World. Complex System Analysis, Mathematical Modeling and Forecasting of Development of the BRICS Countries: Preliminary Results / Ed. by A. A. Akaev, A. V. Korotayev, and S. Yu. Malkov, pp. 246–276. Moscow: KRASAND. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Индия и Китай: модели развития и перспективы в мире. Комплексный системный анализ, математическое моделирование и прогнозирование развития стран БРИКС: Предварительные результаты / Отв. ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, С. Ю. Малков, с. 246–276. М.: КРАСАНД).

Grinin L. E. 2015. A New World Order and Era of Globalization. Article 1. American Hegemony: Culmination and Easing. What is Next? Vek globalizatsii 2: 3–17. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Новый мировой порядок и эпоха глобализации. Ст. 1. Американская гегемония: апогей и ослабление. Что дальше? Век глобализации 2: 3–17).

Grinin A. L., and Grinin L. E. 2013. Cybernetic Revolution and Forthcoming Technological Transformations (Development of Leading Technologies in the Light of Theory of Production Revolutions). Evolution of the Earth, Life, Society, Mind / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, A. V. Korotayev, and A. V. Markov, pp. 167–239. Volgograd: Uchitel. In Russian (Гринин А. Л., Гринин Л. Е. Кибернетическая революция и грядущие технологические трансформации (развитие ведущих технологий в свете теории производственных революций). Эволюция Земли, жизни, общества, разума / Ред. Л. Е. Гринин, А. В. Коротаев, А. В. Марков, с. 167–239. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin A. L., and Grinin L. E. 2015a. Cybernetic Revolution and Historical Process. Social Evolution & History 14(1): 125–184.

Grinin A. L., and Grinin L. E. 2015b. Cybernetic Revolution and Forthcoming Technological Transformations (Development of the Leading Technologies in the Light of Theory of Production Revolutions). Evolution: from Big Bang to Nanorobots / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 256–335. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Grinin A. L., and Grinin L. E. 2015c. Cybernetic Revolution and Historical Process (Technologies of the Future in the Light of Theory of Production Revolutions). Filosofiya i obschestvo 1: 17–47. In Russian (Гринин А. Л., Гринин Л. Е. Кибернетическая революция и исторический процесс (технологии будущего в свете теории производственных революций). Философия и общество 1: 17–47).

Grinin L. E., and Grinin A. L. 2015a. Cybernetic Revolution and the Sixth Technological Wave. Kondratieff Waves: Heritage and the Present / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, A. V. Korotayev, and V. M. Bondarenko, pp. 51–74. Volgograd: Uchitel. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Гринин А. Л. Кибернетическая революция и шестой технологический уклад. Кондратьевские волны: наследие и современность / Отв. ред. Л. Е. Гринин, А. В. Коротаев, В. М. Бондаренко, с. 51–74. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L. E., and Grinin A. L. 2015b. From the Biface to Nanorobots. The World is on the Way to the Epoch of Self-governed Systems (History of Technologies and the Description of Their Future). Volgograd: Uchitel (Forthcoming). In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Гринин А. Л. Оm рубил до нанороботов. Мир на пути к эпохе самоуправляемых систем (история технологий и описание их будущего). Волгоград: Учитель [в печати]).

Grinin L. E., and Grinin A. L. 2015c. Cybernetic Revolution and the Sixth Technological Wave. Istoricheskaya psikhologiya i sotsiologiya istorii 8(1): 172–197. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Гринин А. Л. Кибернетическая революция и шестой технологический уклад. Историческая психология и социология истории 8(1): 172–197).

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2010. Will the Global Crisis Lead to Global Transformations. 1. The Global Financial System: Pros and Cons. Journal of Globalization Studies 1(1): 70–89.

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2014a. Globalization and the Shifting of Global Economic-Political Balance. The Dialectics of Modernity – Recognizing Globalization. Studies on the Theoretical Perspectives of Globalization / Ed. by Е. Kiss, and A. Kiadó, pp. 184–207. Budapest: Publisherhouse Arostotelész.

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2014b. Globalization Shuffles Cards of the World Pack: In Which Direction is the Global Economic-Political Balance Shifting? World Futures 70(8): 515–545.

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2014c. Inflationary and Deflationary Trends of the World Economy, or the Spread of ‘the Japanese Disease’. History and Mathematics: Aspects of Demographic and Social and Economic Processes / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 229–253. Volgograd: Uchitel. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В. Инфляционные и дефляционные тренды мировой экономики, или распространение «японской болезни». История и Математика: аспекты демографических и социально-экономических процессов / Отв. ред. Л. Е. Гринин, А. В. Коротаев, с. 229–253. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2015a. Great Divergence and Great Convergence. A Global Perspective. New York, NY: Springer.

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2015b. Deflation as a Disease of the Modern Developed Countries. Analysis and Modeling of World and Country Dynamics: Methodology and Basic Models / Ed. by V. A. Sadovnichiy, A. A. Akaev, S. Yu. Malkov, and L. E. Grinin, pp. 241–270. Moscow: Moscow Publishing House ‘Uchitel’. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В. Дефляция как болезнь современных развитых стран. Анализ и моделирование мировой и страновой динамики: методология и базовые модели / Отв. ред. В. А. Садовничий, А. А. Акаев, С. Ю. Малков, Л. Е. Гринин, с. 241–270. М.: Моск. ред. изд-ва «Учитель»).

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2015c. Global Ageing of Population and Global Financial System. History and Mathematics 10 (In the press). In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В. Глобальное старение населения и глобальная финансовая система. История и математика 10 [в печати]).

Jotterand F. 2008. Emerging Conceptual, Ethical and Policy Issues in Bionanotechnology. Vol. 101. N. p.: Springer Science & Business Media.

Kapelyushnikov R. I. 2012. How much does Human Capital in Russia Cost? Moscow: NIU Vysshaya Shkola Ekonomiki. In Russian (Капелюшников Р. И. Сколько стоит человеческий капитал России? М.: НИУ ВШЭ).

Khaltourina D. A., and Korotayev A. V. 2010. System Monitoring of Global and Regional Development. System Monitoring. Global and Regional Development / Ed. by D. A. Khaltourina, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 11–188. Moscow: LIBROKOM/URSS. In Russian (Халтурина Д. А., Коротаев А. В. Системный мониторинг глобального и регионального развития. Системный мониторинг. Глобальное и региональное развитие / Ред. Д. А. Халтурина, А. В. Коротаев, с. 11–188. М.: ЛИБРОКОМ/URSS).

Korotayev A. V., and Bozhevolnov Yu. V. 2010. Some General Tendencies of the Economic Development of the World System. Forecasting and Modeling of Crises and World Dynamics / Ed. by A. A. Akaev, A. V. Korotayev, and G. G. Malinetsky, pp. 161–172. M.: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Божевольнов Ю. В.Некоторые общие тенденции экономического развития Мир-Системы. Прогноз и моделирование кризисов и мировой динамики / Отв. ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, с. 161–172. М.: ЛКИ/URSS).

Korotayev A. V., and Bozhevolnov Yu. V. 2012. Scenarios of Demographic Future of Russia. Modeling and Forecasting of Global, Regional and National Development / Ed. by A. A. Akaev, A. V. Korotayev, G. G. Malinetsky, and S. Yu. Malkov, pp. 436–461. Moscow: LIBROKOM/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Божевольнов Ю. В. Сценарии демографического будущего России. Моделирование и прогнозирование глобального, регионального и национального развития /

Отв. ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, С. Ю. Малков, с. 436–461. М.: ЛИБРОКОМ/URSS).

Korotayev A., Goldstone J., and Zinkina J. 2015. Phases of Global Demographic Transition Correlate with Phases of the Great Divergence and Great Convergence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 95: 163–169.

Korotayev A. V., and Grinin L. E. 2012a. Kondratieff Waves in the World System Perspective. Kondratieff Waves. Dimensions and Prospects at the Dawn of the 21st Century / Ed. by L. Grinin, T. Devezas, and A. Korotayev, pp. 23–64. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Korotayev A. V., Malkov A. S., Bozhevolnov Yu. V., and Khaltourina D. A. 2010. To the System Analysis of Global Dynamics: Interaction of the Center and Periphery of the World System. Global Studies as an Area of Scientific Research and Sphere of Teaching / Ed. by I. I. Abylgaziev, I. V. Ilyin, and T. L. Shestova, pp. 228–242. Moscow: MAX Press. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Малков А. С., Божевольнов Ю. В., Халтурина Д. А. К системному анализу глобальной динамики: взаимодействие центра и периферии Мир-Системы. Глобалистика как область научных исследований и сфера преподавания / Отв. ред. И. И. Абылгазиев, И. В. Ильин, Т. Л. Шестова, с. 228–242). М.: МАКС Пресс.

Korotayev A. V., Zinkina Yu. V., Khaltourina D. A., Zykov V. A., Shulgin S. G., and Folomeyeva D. A. 2015. Prospects of the Population Dynamics of Russia. Analysis and Modeling of the World and Country Dynamics: Methodology and Basic Models / Ed. by V. A. Sadovnichiy, A. A. Akaev, S. Yu. Malkov, and L. E. Grinin, pp. 192–240. Moscow: Uchitel. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Зинькина Ю. В., Халтурина Д. А., Зыков В. А., Шульгин С. Г., Фоломеева Д. А. Перспективы демографической динамики России. Анализ и моделирование мировой и страновой динамики: методология и базовые модели / Ред. В. А. Садовничий, А. А. Акаев, С. Ю. Малков, Л. Е. Гринин, с. 192–240. М.: Учитель).

Korotayev A. V., and Khaltourina D. A. 2009. Current Tendencies of the World Development. Moscow: LIBROKOM/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Халтурина Д. А. Современные тенденции мирового развития. М.: ЛИБРОКОМ/ URSS).

Korotayev A. V., Khaltourina D. A., and Bozhevolnov Yu. V. 2011. Mathematical Modeling and Forecasting of the Demographic Future of Russia: Five Scenarios. Scenario and Perspectives of Development of Russia / Ed. by V. A. Sadovnichiy, A. A. Akaev, A. V. Korotayev, and G. G. Malinetsky, pp. 196–219. Moscow: Lenand/ URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Халтурина Д. А., Божевольнов Ю. В.Математическое моделирование и прогнозирование демографического будущего России: пять сценариев. Сценарий и перспектива развития России / Ред.В. А. Садовничий, А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, с. 196–219. М.: Ленанд/URSS).

Korotayev A. V., Khaltourina D. A., Malkov A. S., Bogevolnov J. V., Kobzeva S. V., and Zinkina J. V. 2010. Laws of History: Mathematical Modeling and Forecasting of the World and Regional Development. 3rd ed., rev. and add. Moscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Халтурина Д. А., Малков А. С., Божевольнов Ю. В., Кобзева С. В., Зинькина Ю. В. Законы истории. Математическое моделирование и прогнозирование мирового и регионального развития. 3-е изд., испр.и доп. М.: ЛКИ/URSS).

Korotayev A., and de Munck V. 2013. Advances in Development Reverse Inequality Trends. Journal of Globalization Studies 4(1): 105–124.

Korotayev A., and de Munck V. 2014. Advances in Development Reverse Global Inequality Trends. Globalistics and Globalization Studies 3: 164–183.

Korotayev A., and Zinkina J. 2014. On the Structure of the Present-day Convergence. Campus-Wide Information Systems 31(2): 41–57.

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Bogevolnov J., and Malkov A. 2011a. Global Unconditional Convergence among Larger Economies after 1998? Journal of Globalization Studies 2(2): 25–62.

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Bogevolnov J., and Malkov A. 2011b. Unconditional Convergence among Larger Economies. Great Powers, World Order and International Society: History and Future / Ed. by Debin Liu, pр. 70–107. Changchun: The Institute of International Studies; Jilin University.

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Bogevolnov J., and Malkov A. 2012. Unconditional Convergence among Larger Economies after 1998? Globalistics and Globalization Studies 1: 246–280.

Liang J., Liu X., Tu E., and Whitelaw N. 1996. Probabilities and Lifetime Durations of Short-Stay Hospital and Nursing Home Use in the United States, 1985. Medical Care 34(10): 1018–1036.

Lynch Z. 2004. Neurotechnology and Society 2010–2060. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1031: 229–233.

Malkov A. S., Bozhevolnov Yu. V., Khaltourina D. A., and Korotayev A. V. 2010. To the System Analysis of World Dynamics: Interaction of the Center and Periphery of the World System. Forecasting and Modeling of Crises and World Dynamics / Ed. by A. A. Akaev, A. V. Korotayev, and G. G. Malinetsky, pp. 234–248. Moscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Малков А. С., Божевольнов Ю. В., Халтурина Д. А., Коротаев А. В. К системному анализу мировой динамики: взаимодействие центра и периферии Мир-Системы. Прогноз и моделирование кризисов и мировой динамики / Ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, с. 234–248. М.:ЛКИ/URSS).

Malkov A. S., Korotayev A. V., and Bozhevolnov Yu. V. 2010. Mathematical Modeling of Interaction of the Center and Periphery of the World System. Forecasting and Modeling of Crises and World Dynamics / Ed. by A. A. Akaev, A. V. Korotayev, and G. G. Malinetsky, pp. 277–286. Moscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Малков А. С., Коротаев А. В., Божевольнов Ю. В. Математическое моделирование взаимодействия центра и периферии Мир-Системы. Прогноз и моделирование кризисов и мировой динамики / Отв. ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, с. 277–286. М.: ЛКИ/URSS).

Nefiodow L. 1996. Der sechste Kondratieff. Wege zur Produktivität und Vollbeschäftigung im Zeitalter der Information [The Sixth Kondratieff. Ways to Productivity and Full Employment in the Information Age]. 1. Auflage/Edition. Sankt Augustin.

Nefiodow L., and Nefiodow S. 2014. The Sixth Kondratieff. The New Long Wave of the World Economy. Rhein-Sieg-Verlag: Sankt Augustin.

OECD. 2001. The Well-being of Nations: The Role of Human and Social Capital. Paris: OECD.

OECD. 2014a. Annual Survey of Large Pension Funds and Public Pension Reserve Funds. Report on Pension Funds’ Long-term Investments.

OECD. 2014b. Pension Markets in Focus. Paris: OECD.

OECD. 2015. OECD Stat. Public Pension Reserve Funds’ Statistics: Asset Allocation. URL: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=594.

Papenhausen Ch. 2008. Causal Mechanisms of Long Waves. Futures 40: 788–794.

Perez C. 2002. Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Perez C. 2010. Technological Revolutions and Techno-Economic Paradigms. Cambridge Journal of Economics 34(1): 185–202.

Pride V., and Korotayev A. (Eds.) 2008. New Technologies and Continuation of the Person’s Evolution? Moscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Прайд В., Коротаев А. (Ред.) Новые технологии и продолжение эволюции человека? М.: ЛКИ/URSS).

Shtefan J. 2008. Pension Funds of the USA Lost Two Trillion Dollars. New Region 2, October 8. URL: http://www.nr2.ru/economy/199830.html. In Russian (Штефан Е. Пенсионные фонды США потеряли два триллиона долларов. Новый регион 2, 8 октября.

URL: http://www.nr2.ru/economy/199830.html).

Stiglitz J. E. 2015. America in the Way. Project Syndicate, August 6. URL: http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/us-international-development-finance-by-joseph-e–stiglitz-2015-08.

UN Population Division. 2015. UN Population Division Database. URL: http://www.un.org/esa/population. Date accessed: 17.01.2015.

World Bank 2015. World Development Indicators Online. Washington, DC: World Bank. URL: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/.

Zinkina J., Malkov A., and Korotayev A. 2014. A Mathematical Model of Technological, Economic, Demographic and Social Interaction between the Center and Periphery of the World System. Socio-economic and Technological Innovations: Mechanisms and Institutions / Ed. by K. Mandal, N. Asheulova, S. G. Kirdina, pр. 135–147. New Delhi: Narosa Publishing House.

Zinoviev A. A. 2003. Global Human Warren. Moscow: Eksmo. In Russian (Зи-новьев А. А. Глобальный человейник. М.: Эксмо).

We hear all the time about how technology is bad for us. Since the introduction of computers. Even people working on App Development have the same issues, we spend more time sitting at a desk than moving around at work. We have created this sedentary lifestyle that is causing havoc in our overall life.

We hear all the time about how technology is bad for us. Since the introduction of computers. Even people working on App Development have the same issues, we spend more time sitting at a desk than moving around at work. We have created this sedentary lifestyle that is causing havoc in our overall life.