Photo: UNHCR

The Syrian refugee crisis is one of the worst humanitarian disasters since World War II. It is estimated that more than 11 million Syrians have been forced to flee their homes since the outbreak of the civil war in 2011. More than six million are internally displaced, while approximately 4.6 million have taken refuge in Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, and Egypt, and another one million have sought refuge in Europe. Against that background, it is striking that the United States has accepted only 10,000 Syrian refugees. In contrast, Canada, with a population barely one-tenth the size of that of the United States, has accepted three times more Syrian refugees.

There is considerable interest and concern in the United States as to why so few Syrian Christians are registered as refugees by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and why so few Syrian Christian refugees eventually resettle in the United States.

While religion should not be an issue when it comes to the treatment of refugees, the numbers need to be analyzed to determine what they really mean and how they can be explained. Although Christians are generally represented to be as much 10 percent of Syria’s prewar population, the total percentage of Syrian Christian refugees who registered with the UNHCR is only 1.2 percent [i].

Recent news reports state that only 56 of the 10,000 Syrians refugees who resettled in the United States in 2016 are Christian.[ii] These numbers have led to criticism that the systems in place discriminate against Christians, making it difficult for them to register.

This report, which relies mostly on information gleaned from interviews conducted with people and organizations in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan in June and July 2016, provides contextual explanations of why Syrian Christians are not registering as refugees with the UNHCR.

This report also contains the findings of interviews conducted in the United States with individuals associated with U.S.-based organizations and Syrian religious and activist groups. The broader topic of discrimination and the horrors of the Syrian civil war, including its effects on the Syrian Christian community, should be examined more fully, but are not covered by this report. It should be noted that much of the report contains anecdotal information. Very few organizations or individuals—especially individual refugees—were willing to be quoted on the record, but informal conversations with a number of organizations and individuals made this report possible.

One notable finding is that there are sharply different perceptions in the United States, on one hand, and in Lebanon and Jordan, on the other, about treatment of Syrian Christian refugees: U.S. suppositions of anti-Christian discrimination and systemic difficulties as the possible reasons for the small numbers of this group being registered and resettled as refugees contrasts with the perception, especially in Lebanon and Jordan, that Syrian Christians receive preferential treatment and are resettled at a higher rate than other refugees.

Syria has always been a diverse state with numerous minority and religious groups. The Kurds (in the northeast portion of the country) are the largest national minority group. Next are the Palestinians, who fled to Syria following the 1948 and 1967 Arab-Israeli wars, mostly living in refugee camps administered by the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). Armenians are also a prominent religious and national minority group, living primarily in Aleppo and estimated to number from 70,000 to 100,000 at the beginning of the current civil war. There are also smaller numbers of Turkmen and Yazidis. Most Syrians are Sunni Muslims, but other Muslim sects include Alawites, Shiites, and Druze.

Christian minority groups are estimated to represent seven to 10 percent of the pre-conflict population. Included are Greek Orthodox, Melkite Catholics, Syriac Orthodox, Maronites, and other smaller sects. Most of the Christians are Orthodox, with the largest group centered on the Orthodox Church of Antioch and the Eastern Catholic (or Melkite) Church. Other Christian sects include Armenians, Syriac Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, other Orthodox churches, and a small Protestant community.

The Syrian civil conflict and outflow of refugees

The Syrian civil conflict that began in March 2011 has become one of the greatest human tragedies since World War II. Upward of 400,000 people have been killed, and over five million have been displaced and sought refuge outside of Syria. This does not include millions of Syrians who are internally displaced. The refugee crisis has had substantial impact not only on neighboring countries, but also on the world in general. Most of those displaced have sought refuge in Turkey (upward of two million), Jordan (1.5 million to two million), and Lebanon (one million to 1.5 million). Although Turkey and Jordan have created refugee camps, most refugees—perhaps as many as 85 percent—do not stay in the camps, preferring to reside in urban areas (see Appendix 1). Turkey’s government runs the camps in its country, while the UNHCR administers those in Jordan. Lebanon, which still hosts a significant number of Palestinian refugee camps from the 1948 and 1967 wars, has decided not to create any new official camps. This has the unintended consequence of generating more than the one million refugees, who have subsequently dispersed and settled in communities throughout the country.

The UNHCR is tasked with identifying and registering these refugees and providing for their support (see Appendix 2). The UNHCR has a process for identifying and registering refugees and providing basic foodstuffs and access to medical care. Registration is an important first step for refugees not only to receive aid, but also to join a queue for eventual resettlement outside of Syria, if the refugee so chooses. The UNHCR identification system also records vulnerability, so that those refugees deemed as most vulnerable receive preference for resettlement.

It should be recognized that not all those fleeing Syria register as refugees, or seek to resettle, or accept the system for refugee designation. The process of registering and being resettled is long and arduous. The United States, which accepted in excess of 15,600 refugees [iii] since 2011, has a vetting period that takes approximately two years.

Critical question: Why are there so few registered Christian refugees?

The majority of those interviewed for the purpose of this report asserted that the Assad regime does not threaten Syrian Christians in the same way it threatens others. The ruling Baath party and the Assad regime are avowedly nationalistic. Many of the Syrian Christian refugees interviewed in Lebanon – including some who initially supported the opposition – expressed fear that rebels in Syria appear to have become increasingly more dominated by ‘Islamic radicals,’ leaving little place for them in the opposition. The rise of new opposition or rebel groups, including Jabhat Fath al-Sham (the rebranded Jabhat al-Nusra), and, of course, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), make the Assad regime appear less of a threat to Christians in comparison.

Most Syrian Christians are urban and lived in Aleppo, Damascus, Homs, and smaller cities such as Tartous and Latakia. Wadi Nassarah, or the “Valley of the Christians,” is an interesting exception to urban Christian residence trends. The valley is historically a Christian area, containing around 35 Christian villages. It is also where many urban Christian families, who may have moved to Damascus or Aleppo for better opportunities, either kept a historical family home or built a vacation or retirement home. Since the conflict started, many from volatile areas have either moved to their second homes in the valley or allowed families and friends to occupy them. There are even regime-controlled areas of hard-hit Aleppo that are functioning and not under siege. Most of the hardest-hit areas are rebel controlled, and the Assad government’s use of air power and barrel bombs are examples of its superior and deadly firepower that has destroyed rebel-held areas.

Some Christians have been returning even to devastated cities like Homs. Bishop Issam John Darwich of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church in Zahleh, in Lebanon, currently hosts about 800 Syrian Melkite families. Very few of them have registered with the UN, mostly because they plan on returning eventually to Syria. In June 2016, the bishop stated that about 100 families have returned to Homs.[iv]

According to Anne Richard, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Population, Refugees, and Migration, many Christians within Syria also might feel protected by President Bashar Al-Assad, who himself is part of the minority Alawite offshoot of Islam. In her testimony on Capitol Hill in December 2015, Assistant Secretary Richard reported that “a higher percentage of Christians in Syria support Assad and feel safer with him there.”[v]

Characteristics common among Christians in Syria explain why their numbers are low in registering as refugees and applying for resettlement. Since they tend to be highly urbanized, as previously noted, they benefit from greater government spending and better educational facilities, and therefore have more opportunities to acquire wealth in urban areas than in rural regions.

Christians in Syria tend to be more highly educated than other minorities; this is due to historical factors as well as current circumstances. Historically, in Ottoman territories during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, “American missionaries established schools, printing presses, hospitals, and other institutions. Ultimately, very few converted to evangelical Christianity in the way that American missionaries might have hoped.”[vi] After 1856, Ottoman government authorities continued to recognize the de facto ban on Muslim out-conversion, while Muslim communities at the grassroots level stood ready to apply legal and social sanctions against apostates from Islam.”[vii] These Christian missionaries established institutions throughout the great cities of the time, perhaps the most famous of them being the American University of Beirut, founded by Daniel Bliss in 1866. The Catholic community, alarmed by these activities, created its own series of schools and universities, such as St. Joseph’s University, founded in 1875, also in Beirut. Such undertakings were repeated in the great cities of Syria, including Aleppo and Damascus. Christian and Jewish children attended these missionary schools, but the Muslim ulema [viii] tried their best to prevent Muslim children from attending, instead urging them to study in the traditional madrassas [ix]. This meant that by the beginning of World War I, “Christian and Jews had much higher literacy rates than did Muslims.”[x]

Rami Khouri, a well-known scholar and journalist and director of the Issam Fares Institute at the American University of Beirut, called the propensity for Christians to seek education the “Minority Syndrome,” which he describes as the belief that education would be their ladder to success.[xi]

Having higher literacy rates and embracing “Western schools” led to Christians – as a whole – having higher penetration in professions such as medicine, dentistry, teaching, and engineering. As a result, Christians tend to earn higher incomes and possess degrees and professions that are in greater demand in other places in the Arab world or elsewhere, thereby eliminating the need for them to register as refugees. (Jordan and Lebanon are exceptions to such portability of professions, as those countries have bans on refugee employment.)

Another factor against Syrians registering as refugees is the fear of appearing disloyal to the regime. With Syrian Christians having on average more wealth than Syrians in general, it follows that they may own an apartment, a business, or some land, or have a government job with a regular paycheck they still are eligible to collect. The majority of individual refugees, officials in aid organizations, and UNHCR outreach workers interviewed stated that most Syrians believe the mokhabarat [xii] would somehow discover the act of registering as refugees, and that it would be considered disloyal to the Assad regime and the Baath party potentially putting relatives in danger or leading to the confiscation of one’s Syrian property or business. Numerous interviewees expressed how difficult it is for someone from the United States or even Lebanon to understand the stresses of life in Syria because of the pervasive presence of the mokhabarat, even during peacetime. It was reported that even during peacetime, Syrians had to report foreign guests to the secret police.[xiii]

There is, in addition, a stigma associated with the status of being a refugee so much so that people with resources want to avoid it at all costs. Based on discussions and interviews with numerous Syrian Christian refugees and Christian aid and civil society organizations in Lebanon, it became obvious that a great many Syrian Christians had the ability to rent apartments in Lebanon and did not want to register as refugees. They planned on waiting out the war—or at least waiting for the fighting to end in areas where they had lived.[xiv]

A further consideration is that many Syrian Christians worked for the government. Syria has a mixed but mostly centrally planned economy, with a very large government sector. The government regularly pays its bureaucrats, even if their place of employment no longer exists. For example, some Syrian Christians in Lebanon still receive a regular government paycheck. This particularly applies to refugees who have arrived in the last year or so, despite being prohibited by the Lebanese government from entering the country. Aid agencies report that many of the recent refugees are women who come to Lebanon with 17-year-old sons to avoid their conscription into the Syrian military, while the fathers may remain in Syria to either work or receive a paycheck.

Where have Syrian Christians fled?

Syrian Christians overwhelmingly choose Lebanon as a refuge over Jordan or Turkey. According to the UNHCR and U.S. embassy officials, virtually no Christians reside in Jordan [xv] and Turkey.[xvi]

Syrian Christian refugees choose Lebanon for three principal reasons: First, Lebanon has a large and well-organized Christian community, including churches and institutions. Its churches have developed a large and important civil society network throughout the country. Second, most Syrian Christians have well-developed kinship ties in Lebanon, or their home churches have branches in Lebanon. Third, while most Syrians flee fighting and bombardment, those refugees—especially Sunnis—who fear the government tend to escape via the north (to Turkey) or the south (to Jordan). For Syrian Christians, avoidance of areas of government control is not a concern, and they are likely to choose Lebanon as a destination, despite its recent nominal ban on refugees.

Most Syrian Christian refugees avoid refugee camps by choice, fleeing to areas where they have family connections or can work. They know Lebanon does not have formal refugee camps for Syrians. The Lebanese government decided against opening camps on the basis of its experience with official and formal camp facilities created by the UNRWA for Palestinian refugees who fled to Lebanon during the 1948 and 1967 Arab-Israeli wars.

Prior to May 2015, when the UNHCR stopped registering Syrian refugees in Lebanon, it operated numerous mobile registration teams, as well as walk-in registration at facilities throughout the country, including at its headquarters in the Ramlet El Baida neighborhood of Beirut. These teams comprised Lebanese, international UN employees, and Syrians permitted to work in the country. While the UN does not keep records of the religious affiliations of team members, it is highly likely -given Lebanon’s large Christian population – that Christians were involved in these teams. A perception of anti-Christian bias in registration protocol would seem unfounded. UNHCR officials confirmed this view during discussions on the subject.[xvii]

The proportion of Christians among the 102,000 Syrians who came to the United States through work, study, or other visa programs since 2011 is unknown. It seems highly likely, however, that Christians have constituted a significant number of those Syrians who arrive in the United States without official refugee status.[xviii]

A large number of Syrian refugees interviewed for the purpose of this report expressed their desire to return to Syria when the conflict is over, or even when the fighting ends in their area. Outreach workers from the UNHCR and Caritas International confirmed these sentiments. Bishop Darwich reported that 100 of the 800 families receiving assistance from his church in Zahleh returned to Homs in May 2016.[xix]

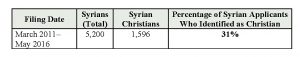

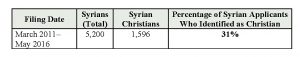

While the Department of Homeland Security does not keep religious affiliation data in the visa applications of people entering the United States, it does record religious affiliation information for those who apply for asylum. Asylees differ from refugees because their status is determined after they arrive in the United States. Unlike UNHCR-registered refugees, asylees are not vetted, and simply arrive at the border or have already entered the United States and are asking for asylum. According to data from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), as illustrated in the chart below, Christians accounted for 31 percent of all Syrian asylee cases in the United States from March 2011 to May 2016. [xx]

Most of the refugees interviewed, who want to skip the UNHCR line, do not have the United States as their top destination choice, reporting instead they find it easier to travel to Europe, Canada, or Australia, and that these destinations are more appealing in terms of services and benefits offered. A major factor in the refugees’ shared sentiment is that they consider the U.S. vetting process too long and burdensome. It takes roughly two years for refugees to be thoroughly investigated to rule out potential ties to radical Islamist groups. The process is also not considered flexible enough. For example, if one step is missed—either through the fault of the refugee or if U.S. personnel are unable to be in the field, such as in Lebanon for security reasons—the whole process restarts.

Most of the refugees interviewed, who want to skip the UNHCR line, do not have the United States as their top destination choice, reporting instead they find it easier to travel to Europe, Canada, or Australia, and that these destinations are more appealing in terms of services and benefits offered. A major factor in the refugees’ shared sentiment is that they consider the U.S. vetting process too long and burdensome. It takes roughly two years for refugees to be thoroughly investigated to rule out potential ties to radical Islamist groups. The process is also not considered flexible enough. For example, if one step is missed—either through the fault of the refugee or if U.S. personnel are unable to be in the field, such as in Lebanon for security reasons—the whole process restarts.

Are refugee camps hostile to Christians?

Some commentators have speculated that Christians fear living in refugee camps because of religious oppression or perceived loyalties to the Assad regime. This, they surmise, accounts for the failure of the UNHCR – which operates in the camps – to register a greater number of Syrian Christian refugees.

This explanation, however, is not in accord with the fact that only 10-15 percent [xxi] (Also see Appendix 1) of all Syrian refugees reside in refugee camps, while, as stated before, the vast majority of Syrian Christians flee to Lebanon, a country that—as a matter of policy—does not have any formal or official Syrian refugee camps.

The conflicted position of Syrian churches

Christianity has a long history in Syria, with the notable conversion of St. Paul the Apostle on the road to Damascus. Today’s churches are concerned about their continuing presence and viability in Syria if their members become registered refugees and eventually resettled in foreign lands.[xxii]

Perceptions of favoritism

It is interesting that in the United States, many (who point to the low numbers of registered refugees as evidence) perceive that institutions in the Levant discriminate against Christians. Perceptions in the Middle East, however, are quite the opposite. While only 1.2 percent [xxiii] of registered refugees are Christian, the actual resettlement rate is 2.5 percent [xxiv], a fact that is interpreted as meaning Christians are favored when it comes to resettlement. While the UNHCR and U.S. resettlement processes are faith-blind other refugee programs and countries like Canada and Australia take other factors into account, including education and kinship ties (i.e., having relatives in host countries – a factor that increases one’s resettlement chances). Moreover, the percentage of Arab Christians in the diaspora is much higher – for example, in the United States approximately 65 percent of Arab-Americans are Christian [xxv]. As Syrian Christians have more kinship ties to the West, they benefit more from resettling in those countries that put emphasis on kinship. Although no interview participants spoke on record, all interlocutors – particularly Christian nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) – were adamant that Christians are not and should not receive preferential treatment, and maintained that the perception of favoritism is harmful. All of the Christian organizations that participated in interview sessions concurred with this fear of favoritism.

A Case in Point: Syrian Armenians

The total numbers of Armenians in pre-civil conflict Syria is estimated to have been anywhere between 70,000 and 100,000, with the overwhelming majority living in Aleppo. The Armenian community in Syria is generally economically successful and constitutes an important part of Syria’s merchant and professional class. Armenians sought refuge in Syria following Turkey’s genocidal campaign against them from 1915 to 1917. While most Armenians subsequently left for Western Europe or the United States, the community that stayed in Aleppo prospered.

Armenians in Syria are wealthier than the average Syrian, and highly clustered around medical professions and trade. They are loyal to the Baath party, having made a community-wide deal with the burgeoning party in the late 1970s to maintain control over their own schools. In this sense, there is a tradition of gratitude among Armenians for the support Syria gave them following their mass displacement from Turkey. This is compounded by the support a secular government engenders among minority Christian groups. In essence, Syrian Armenians are similar to most Syrian Arab Christians in that they are not disloyal to the Baath regime.

Most of Aleppo’s Armenians have fled – only around 5,000 have remained behind. Some have relocated to safer areas within government-held Syria, especially Damascus, Kassab, and Latakia. In addition, while some have been internally displaced, a large number of Syrian Armenians have fled Syria, going to Lebanon and then elsewhere. For historical reasons, Syrian Armenians do not wish to travel or flee to Turkey.

Syrian Armenians are an example of a Christian minority group that has kinship ties in the United States and the ability to obtain foreign passports to leave troubled areas of Syria. Syrian-Armenians are able to obtain citizenship and passports from the Republic of Armenia, which – as of July 2016 – was the only foreign government to have a functioning consulate in Aleppo. The Armenian consulate waives all fees to those who can prove Armenian heritage. Like other Christians, Syrian Armenians do not register with the UNHCR in high numbers. Syrian Armenians have sought refuge throughout the world based on kinship ties. Some have looked to Lebanon, which already has a large and well-established Armenian community. Approximately 16,000 [xxvi] have fled to Armenia, with only 500 having registered as refugees with the UNHCR. Syrian Armenians use their Armenian passports to travel legally to other countries and evidence points to a trend toward traveling and resettling in Canada, Australia, and the United States. Lebanon, which has stopped the inflow of refugees from Syria, allows Syrian Armenians who hold Republic of Armenia passports to travel to Beirut International Airport if they have one-way tickets to Armenia.

According to Serop Ohanian, the Lebanon field director of the Howard Karagheusian Association, a well-developed Armenian social service organization, approximately 16,000–20,000 Armenians have moved to Lebanon, where most have family members. They have settled in the historic Armenian community of Bourj Hammoud and the Bekaa town of Anjar. Mr. Ohanian and the outreach staff at the association actively encourage these refugees to register with the UNHCR, but most do not. Sarkis Barklian, an Armenian activist in Washington, DC, echoes the same sentiment as the Armenian associations in Beirut, reporting that most Syrians Armenians do not register as refugees.

Conclusion

It appears clear that the small number of Syrian Christians who have registered with the UNHCR and the even smaller number of those who have resettled in the United States do not substantiate evidence of pervasive anti-Christian discrimination. Theories that Christians are reluctant to go to refugee camps and thus are not registered by the UNHCR ignore the fact that almost all Christian refugees go to Lebanon (which does not permit official or formal refugee camps for Syrians) and avoid going to Jordan and Turkey (where there are formal and official camps).

Better explanations for the low numbers can be found in such factors as stigma, concern about regime reprisals, availability of resources and kinship ties for alternative actions, and hope for eventual return to Syria. Syrian Christians who wish to resettle elsewhere are using other means to go to foreign countries, as evidenced by USCIS data showing that in 31 percent of all recent cases involving Syrians seeking asylum in the United States, the applicants are Christian.

Notes

[i] The Hill, ‘Critics Wrong on Christian Syrian Refugees,’ December 20, 2015.

[ii] Elliot Abrams, ‘The United States Bars Christian, not Muslim, Refugees from Syria,’

Pressure Points blog (Council on Foreign Relations), September 9, 2016.

[iii] “Refugee Arrivals From January 1, 2011 through October 27, 2016.” Refugee Processing Center. Accessed November 4, 2016. “Refugee Arrivals from January 1, 2011 through October 27, 2016.” Department of State. Accessed November 4, 2016. http://www.wrapsnet.org/admissions-and-arrivals/

[iv] Interview with Bishop Issam Darwich in Zahleh, June 28, 2016.

[v] The Hill, ‘Critics Wrong on Christian Syrian Refugees,’ December 20, 2015.

[vi] Heather J. Sharkey, American Missionaries in Ottoman Lands: Foundational Encounters, 2010, 2.

[vii] Ibid, 9.

[viii] The Arabic term for a recognized body of Islamic scholars.

[ix] The Arabic term for school; in this context meaning traditional Islamic religious schools.

[x] Bruce Masters, Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Arab World, Cambridge University Press, 2001, 156.

[xi] Various interviews and discussions with Rami Khouri in May and June 2016.

[xii] The Arabic term for intelligence agency.

[xiii] Numerous interviews with refugees and various Christian relief organizations in Lebanon, June and July 2016.

[xiv] Meetings with refugees in late June and early July 2016; meetings with leaders, including Father Karam, and outreach workers from Caritas (a Catholic international aid organization). Michel Constantin of the Pontifical Mission echoed this view and stated at a June 21, 2016, meeting at the Pontifical office in Sin el Fil that most middle-class and upper-class Syrian Christians did not want to register as refugees, and, in spite of having to flee their homes, donated monies to Lebanese Christian charities to help other Syrians in need.

[xv] U.S. Embassy in Amman, Jordan, stated in e-mail correspondence on June 14, 2016, that “Jordan does not see Christian refugees from Syria because they either did not flee Syria or fled to Lebanon or Turkey.”

[xvi] Discussions with U.S. Consular officials in Adana, Turkey, on June 16, 2016, during which one official stated: “My knowledge is generally limited, as the number of Christian refugees in Turkey is quite small and often off the grid. My understanding is that many Christians opted to flee towards more regime-held territories and away from ISIL and Sham Front-held territory, which happened to be along the border with Turkey.”

[xvii] Meetings and interviews at UNHCR headquarters, week of June 20, 2016, in Ramlet El Baida, Beirut.

[xviii] The Hill, ‘Critics Wrong on Christian Syrian Refugees,’ December 20, 2015.

[xix] Interview with Bishop Issam Darwich in Zahleh, June 28, 2016.

[xx] E-mail correspondence from USCIS, compiled from case management data, June 13, 2016.

[xxi] ‘Syria Regional Refugee Response.’ Accessed November 8, 2016. UNHCR Inter-Agency Data Portal, http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php.

[xxii] Numerous meetings with church officials in the United States and Lebanon.

[xxiii] The Hill, ‘Critics Wrong on Christian Syrian Refugees,’ December 20, 2015.

[xxiv] Meetings and interviews at UNHCR headquarters, week of June 20, 2016, in Ramlet El Baida, Beirut.

[xxv] “Arab-Americans: An Integral Part of American Society”, Arab-American National Museum, Dearborn Michigan, http://www.arabamericanmuseum.org/umages/pdfs/resource_booklets/AANM-ArabAmericansBooklet-web.pdf.

[xxvi] Huffington Post, ‘Armenia and the Syrian Refugee Crisis,’ March 2, 2016.