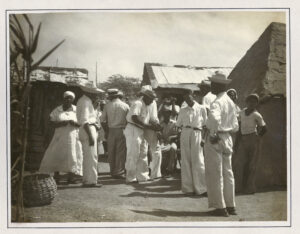

Photograph by Benjamin Gomes Casseres

Photography played a central role in the life of my family when I was growing up in Curaçao. This was certainly not the case for most others in the nineteen fifties and early sixties as it is today, when everyone carries a camera in their pocket and visual culture dominates our life. Then it was a matter of privilege that not many had.

Paíto, as we called my maternal grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres, began to photograph as a young man before 1910, and continued to do so throughout his life. Undoubtedly, he had the time and resources to devote himself to his passion of black and white photography. His many photo albums attest to his outstanding talent as an artist.

As the co-owner of a local camera store, my father, Frank Mendes Chumaceiro, and my mother, Tita Mendes Chumaceiro, had access to the latest equipment, allowing my father to become a pioneering cinematographer on the island, while my mother took color slides, having shifted her artistic talents from painting to photography. Through the years, she won many prizes with her color slides, and her photos of the island’s different flowers were chosen for a series of stamps of the Netherlands Antilles in 1955.

Together, my parents edited my father’s films into documentaries with soundtracks of music and narration and graphically designed titles and credits.

Sometimes these films were commissioned by various organizations and government institutions, including the documentation of visits by members of the Dutch royal family. Movie screenings were regularly held in our living room and at the houses of family and friends who would invite my parents to show their work, as well as at some public events. That was our entertainment in the nineteen fifties, long before television came to the island.

Both my brother Fred and I owned simple box cameras from a young age, working up to SLR cameras as we grew older. Still, I did not take photography seriously as an art until the digital age, when I began to feel I could finally have more control over my output. That was in 2005, when I got my first digital point- and-shoot camera, gradually professionalizing my equipment through the years.

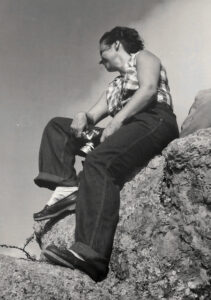

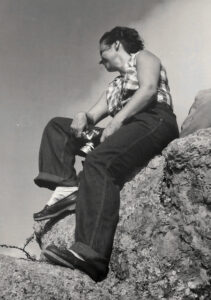

My father and mother with their cameras on top of the Christoffel, 1956, photographer unknown

It was only recently that I began to think about the many ways my rich photographic lineage impacted my life and the directions I have taken as an artist, how it has influenced the development of my own photography. I have discerned six ways that account for this influence by my background – ranging from the circumstances in which the photographs were produced and viewed, to the attitudes that underlie the practice of photography as an art.

A. A treasure trove of photographs

Countless photo albums could be found in our home in Curaçao, with photos by both my parents in their younger years, and later by my brother and me.

After Paíto died in 1955, my mother inherited his albums with family photos, as well as albums with larger prints of his more artistic photographs. Paíto’s family albums documented his leaving Curaçao for Cuba with my grandmother in 1912, where he joined another member of the Curaçao Sephardic Jewish community in buying a sugar cane plantation, which seemed a good business opportunity that also sparked his adventurous spirit.

My mother, Tita, her sister Luisa, and their much younger brother Charlie were born in Havanna. Paíto took their photos from infancy through their teenage years, mostly studio photos often printed in sepia, with the children dressed up for costume parties and other special occasions, posing with their toys and bicycles and with their friends. Paíto would set up his studio in a closed balcony in their house in Havanna with special lighting and curtains or a large painting of a landscape in the background.

The albums also contain photos of their excursions to the beach, where the children learned to swim at an early age, unlike their Curaçao agemates of the same social class, as well as many photographs of trips to the sugar cane plantation, a day’s train ride from Havanna, showing various stages of sugar cane growth and sugar production. With the fall of sugar prices in the twenties, the family was forced to move to a small town much closer to the plantation, where life would be less expensive. Those were exciting years for my mother, when they would play tennis on an improvised court, and ride horses into the fields – years that laid the foundation for her love of nature.

In 1929 my grandparents, returned to Curaçao with their Cuban-born children – totally bankrupt. With the help of his extended Curaçao family, my grandfather was able to establish himself again in business. Here he continued to photograph – landscapes and people in the Curaçao countryside, and especially his grandchildren playing in the yard of their house in Schaarloo, as well on his photographic excursions in nature.

The many photo albums in our house encouraged the ritual of listening to our family members’ stories, to imagine growing up in a different country. In today’s era of digital photography and especially after the cellphone camera came into popular use, every event in life is recorded, and immediately shared on social media. But do we preserve these photographs? Do they remain for others to see, in later generations? Do we view them together, telling their stories?

I am fortunate to have grown up with such a wealth of photographs to document our family history, to bring back memories that have strengthened my sense of who I am, that have fostered a sense of security and connection to the past and to a loving family. It is a sense of grounding. Clearly, many others who grew up in less secure material and emotional circumstances, did not have the same visual record of their families and of their own early years, especially people whose lives were uprooted and had to flee, leaving all visual relics behind.

B. The photographic excursion

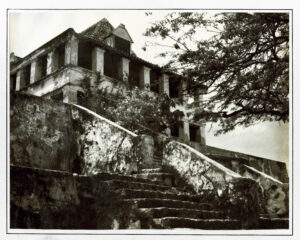

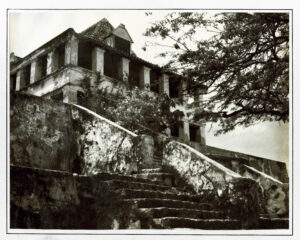

The many Sunday trips with Paíto to the Curaçao countryside were what planted the seeds of my own spirit of exploration in nature. He took photos of us, his grandchildren, climbing heaps of salt mined from the island’s saltpans or resting under the huge mango or coconut trees in the shady groves. On these trips Paíto also took photos of old abandoned plantation houses, the ruins of cisterns or stone bridges from the times of slavery, and of the North Coast where the wild sea would splash against the rocks.

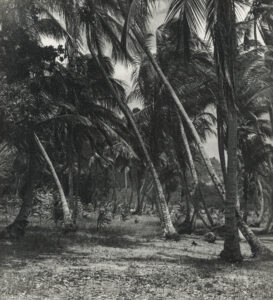

Photograph by Benjamin Gomes Casseres

Access to many of the island’s most beautiful places indeed depended on privilege – to have the right connections to people who owned private plantations, to get permission to enter what was private property and closed to most of the island’s population, often due to racial discrimination. All that, added to the fact that photography in those years was an expensive undertaking, and many could not afford the equipment, the development, and printing of the exposed film.

Owning a car that allowed one to travel on the dirt roads outside the city was also a question of financial privilege. Paíto had a chauffeur who drove his shiny black car and who would clean off the dust and mud when he returned. I don’t remember if Paíto drove himself within the city, but on these excursions, it was Marty, the chauffeur who did the driving, allowing Paíto to fully concentrate on his photography and not to worry about losing the way or getting stuck on the bumpy country roads.

Our photographic excursions continued with my own parents, when they made documentary films about the island, while my mother would take her beautiful color slides. Particularly the nature film “Rots en Water” in 1956, took us to many wild places on the island – to climb the Christoffel for the first time, the highest hill on the island, before there was a park that laid easier access roads;

to explore the cave of Hato with a guide carrying a torch of a dried datu organ-pipe cactus; and to visit the eastern tip of the island, where few would get permission to enter.

My own love of the countryside led to my becoming an avid hiker, going on treks especially in the deserts of Israel, where I moved after attending college in the US. It was while hiking that I started to photograph more seriously, as an art. I was excited to discover how framing through the lens allowed me to penetrate deeper into the landscape, into the textures of the rocks, the interstices between them, as I sought abstractions and a sense of place.

C. Being the subject of the photograph

I was the only girl among Paíto’s four grandchildren. He loved to say, in Spanish, “tres varones y una hembra”, three males and one female, terms that refer to the gender of animals but were clearly meant in an affectionate way and made me feel special. His fourth grandson was born just a month after his death and was named after him.

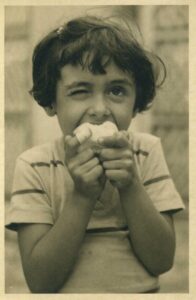

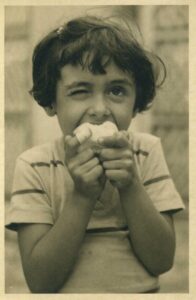

Photograph of me, by Benjamin Gomes Casseres, around 1952

As the only girl, I was his favorite subject. Perhaps also because I was always a calm and introverted child, able to concentrate on what I was doing without being aware of his photographing me. He did not have to ask me to pose, which might have been annoying. He captured so many different faces of me – pensive, deep in thought, playful and mischievous, or bursting out with joy – as if he could see deep inside me. Through his photographs, I came to know myself.

The attention I got from being photographed so frequently gave me a sense of being loved, being special. That feeling was strengthened by the home movies that my parents took of me dancing my improvisations to the records playing on our gramophone, and of my brother and I riding our bikes in the yard, walking on stilts, or acrobatically climbing between two walls in a narrow passage. Seeing those movies through the years reminded us of that love, while also shaping our memories of childhood.

Photograph of me, by Benjamin Gomes Casseres, around 1952

D. Understanding Photography as Art

In the summer of 2006, only a few months before my uncle Charlie died, I interviewed him about Paíto’s photographic practice. He made a drawing of the camera Paíto used in his earlier years as a photographer, the Graflex – a pioneering camera with extension bellows. Paíto would send his photos to be developed in a laboratory in England and he drew lines on the contact prints, indicating where they should be cropped, then sent them back to England with the negatives to be enlarged. Long before Photoshop, he would ask the laboratory to add a sky from a different photo to one of his landscapes. It must have taken a very long time to get the finished photos when mail was mostly carried by ship across the Atlantic.

Paíto’s photographs were admired immensely, though I am not sure if anyone else who was not a family member or friend would see them, as his photographs were never part of a public exhibit – they were in family photo albums, to be viewed only in intimate circumstances. I do not even remember seeing them framed on the wall. Paíto was known in our circles, the Sephardic Jewish community, as one who photographed beautifully – though I am not sure if he was referred to as an “artist”. I always understood his work was different from the snapshots that others made, I could tell there was a lot more to these black and white photographs that were carefully composed, beautifully capturing a different era, mystery, serenity, and longing.

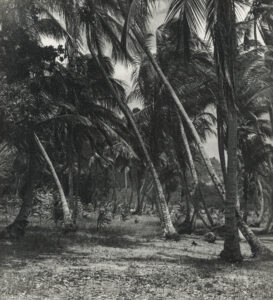

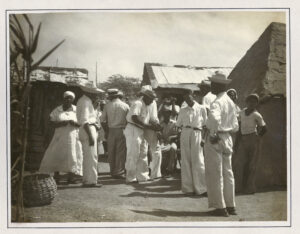

Photograph by Benjamin Gomes Casseres

As a child, I would observe how he worked with depth and devotion – never cutting corners. I noticed his patience, measuring light with an external light meter, figuring out the exposures, choosing the right angle, waiting for the sun to come out from behind the clouds. It was not a question of capturing the moment – but of looking deeper and further into a place and time – all for just one final image. Then he would select the best shots from his many prints, pasting them in his albums, after carefully drawing guidelines on the pages.

I must have understood at an early age, that is how you do art. That this is the seriousness with which the artist works. I am also one who goes through a long process to arrive at the final work, though I don’t believe I have the patience and sense of perfection he had.

Perhaps I also developed a feel for composition by looking at his photographs, intuitively understanding what made them special, as well as how he captured a feeling of mystery, space and distance in his work. I certainly noticed his subject matter – a romantic preference for remnants of the past, old plantation houses, ruins of forts and towers, a lonely house in the fields, the peaceful atmosphere in the old groves of tall, shady trees – the hòfis – that he set as the goal of his excursions, ships sailing away into the distance, as well as his attraction to the old crafts, trades and festivals that were slowly disappearing from the island.

E. Witnessing teamwork

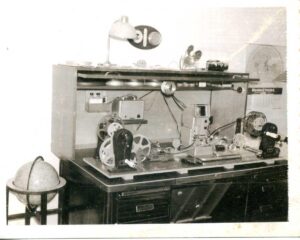

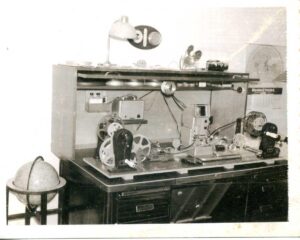

My parents’ editing setup – photo by Frank M. Chumaceiro

My parents started out by making family films and went on to create a large body of mostly documentary films. Their studio was in our living room and study, complete with editing machine, sound equipment, projector, and portable screen. They were assisted by the writer Sini van Iterson in their very

early days and later by others, most notably Jan Doedel as narrator and sound technician.

“Curafilms” is what they called their joint venture. The titles always said: “by Frank and Tita M. Chumaceiro”, without specifying the functions of director, cinematographer, editor, art director, sound designer. Though it was my father who held the film camera and physically spliced the film in the editing machine on the desk in his study, my mother was a full participant in all the stages of

production – sharing her creative insights; scouting locations; discussing the editing options and coming up with new ideas. To have parents doing creative work, and especially when they do it together, was not the norm in the environment I grew up in.

In many ways it was also a project of the entire family, as our parents always shared their ideas with us, and most of the time, we participated in the search for locations and were present at the filming of the movies that involved excursions to lesser-known places of the island. Even when I was still in elementary school, they would share their thoughts about the making of each film with us, and we were there to watch the film-in-progress when they projected it its various stages on the screen in our living room. However, when they worked at night, we had to go to sleep, and I was upset I could not be part of the action.

I learned from my parents the benefits and pleasures of teamwork, even though I am a loner, preferring to do all the work by myself, not because I need to get all the credit, but rather out of a need to be self-sufficient. When I was a curator, and the director of the Antea Gallery for feminist art that I founded in Jerusalem, together with another artist, Nomi Tannhauser, I worked closely with the artists we exhibited, as well as with other curators, when it was a co-curated exhibit. There is a tremendous joy in working together, inspiring each other, and the feeling of satisfaction in completing a shared project, when the finished work is more important than the ego.

Photograph by Benjamin Gomes Casseres

F. The photographer as both outsider and insider

Studying Paíto’s photographs, I realize that what made them so remarkable is that he saw beyond the familiar, exploring the boundaries of what is seen with the eyes, what it means, what it evokes, seeking to see the aura of his subject.

It is an act of looking deeper and further into space and time. In his photographs of ruins and relics he conjures a whole era that once was and is no more; in his closeups he penetrates deeper into the details of what is; and in photos of his landscapes and those of the ships he loved to photograph, he looks out into the distance, past the horizon.

The act of photographing required him to take a step back, to look from the outside, at a distance, with the attitude of the outsider. But the photographic act also required him to penetrate beyond the surface, to have the intimacy of the insider, to look lovingly, to acknowledge the other as a subject. In other words, his photography shows that he was both insider and outsider.

With this realization of the outsider/insider stance that is inherent in the practice of my grandfather’s photography, I have come to better understand my own relation to the medium, being myself both an insider and outsider to my native Curaçao, which I left in 1965, and where I return only as a visitor.

I arrive at the island with the eyes of the outsider – even being a bit of an outsider as I was growing up – but with an insider’s familiarity. I am searching for something – perhaps of the past, perhaps of the hidden secrets that eluded me as a child yet continue to fascinate me today. As I photograph the island, I deepen my vision as outsider/insider as I develop my art, seeking to look beyond the surface, into the interstices, deep into the unconscious – thankful for everything my photographic lineage has given me.

Photograph by Benjamin Gomes Casseres

All photos copyright Rita Mendes-Flohr

Jerusalem, May 21,2024

For my own photographs, see www.ritamendesflohr.com

With the arrival of the new Dutch cabinet under prime minister Schoof, we will witness the ideology of the PVV put into practice. How will the ideas of the PVV be realized in daily policy?

With the arrival of the new Dutch cabinet under prime minister Schoof, we will witness the ideology of the PVV put into practice. How will the ideas of the PVV be realized in daily policy?

07-04-2024 ~ Last month’s European Parliament elections did not bring about the ultimate breakthrough of the far right as some had feared. They are gaining influence though, especially because the lines between them and forces in the political center are blurring. Consequently, we will have to look to the left to stop their surge.

07-04-2024 ~ Last month’s European Parliament elections did not bring about the ultimate breakthrough of the far right as some had feared. They are gaining influence though, especially because the lines between them and forces in the political center are blurring. Consequently, we will have to look to the left to stop their surge.