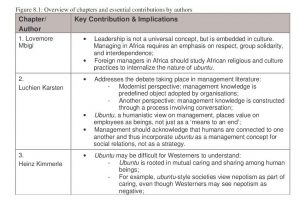

Prophecies And Protests ~ Managing In A Rural Context: Notes From The Frontier

In fact, my philosophy does not allow of the fiction which has been so cleverly devised by the professors of philosophy and has become indispensable to them, namely the fiction of a reason that knows, perceives, and apprehends immediately and absolutely. (Arthur Schopenhauer, The world as will and representation, 1844 (1966: xxvi)).

In fact, my philosophy does not allow of the fiction which has been so cleverly devised by the professors of philosophy and has become indispensable to them, namely the fiction of a reason that knows, perceives, and apprehends immediately and absolutely. (Arthur Schopenhauer, The world as will and representation, 1844 (1966: xxvi)).

Introduction

These notes from the frontier challenge management approaches at all levels, from the management of international relations to the management of an enterprise. Building on a growing literature which questions the so-called Eurocentric approach, this essay challenges the adequacy of political correctness in this furious debate, which has come to so dominate the globalisation thrust of the developed world. These notes from the frontier are presented from the particular frontier in which the author lives and works. To some extent it is a personal observation, but one grounded in research, scholarship and participant observation. The notes bring together a number of observations both of the particular frontier of the author as well as those in the USA, Canada, Europe, Asia, Mexico and elsewhere in Africa. It is a work in progress that attempts to reflect upon the dynamics that underlie the emerging crisis of cultural understanding and misunderstanding in order to find ways to ameliorate the inevitable conflicts if something does not change.

These notes attempt to draw a broad picture of a myriad of complex dynamics as well as ground these thoughts in the nitty-gritty of management in a rural context. It is clearly incomplete as such broad tapestries always are. It is broad, not for the sake of being grand, but because the view of the world from the tribal frontier is very different, and questions some of the widely held beliefs that may seem true from the centres of modernity or other particularities. That globalisation is the mobilization of elites worldwide is not in doubt; however, it faces a danger of losing touch with the feelings and thoughts of those on the ground. It is a dangerous game to play that is, perhaps, begetting a growing reaction to Eurocentrism in general. These notes talk to the issues involved with resolving this basic conflict of the 21st Century, perhaps, contributing to the search for the right questions. This chapter, therefore, roams from the global to the local, intertwining a number of threads, but from a perspective based in a frontier of globalisation.

The notes present the view from a particular context, the particular frontier between globalisation and tribalism in the northernmost province of South Africa, Limpopo Province. It reports the observations of a participant observer, an urban born white South African who has had the fortune to work and live on this frontier for the past 15 years, as well as travelling widely over that time. It also draws on research conducted on specific issues underlying management in this rural context, such as the issues of identity and migrancy as they impact both this rural particularity and other frontiers, including migrants to the so-called developed countries and their particularities worldwide.

This chapter is presented as a contribution to furthering the broader conversations concerning management on the frontiers of globalisation. The frontier is where globalisation and particularities interface, whether in a First or Third World context. More narrowly this contribution forms part of a conversation towards the development of a management style appropriate to the rural Southern African context, in which particularity the author is immersed. The notes contribute to the debate around Afrocentric management. It is somewhat of a heuristic montage attempting to bridge the gap between local and global perspectives and especially the perspective of the particularities vis-à-vis the forces of globalisation. In a sense these are notes from the frontier between modernity and tribality, in this particular case.[i] It is not a clash of civilizations as Huntington (1993) would have us believe; rather it is a clash of histories and trajectories, a clash of values on a myriad of fronts. One must be careful not to trivialize this complex dynamic between cultures and values to a good guy – bad guy scenario. Difference is a matter for respect and not for the cheap politics of maligning the other. The crux of the matter is that you cannot expect others’, cultures, societies and particularities, to accept the dominating culture in its entirety. Management at all levels needs to urgently acknowledge the ‘other’, the particularities’ right to self-determination.

Coming to terms with particularity

In the 21st century, we are all confronting different complexes of a multitude of processes variously called individuation, socialisation, urbanisation, globalisation, nomadisation or whatever. However, we are all ‘modernising’ in our own way, variably influenced by others, but with clearly different starting points, histories, trajectories, cultures, values, perspectives and contexts. These constitute a people’s particularity.

The Boers

South Africa provides a unique window on these processes. South Africa’s rainbow of particularities is unique, partly because of South Africa’s rich and diverse cultural mix, but also, because of the Apartheid Regime’s maintenance, manipulation and ‘preservation’ of traditional societies, or tribalism. It must be recognised that for all its ills, Apartheid resulted from two impulses. First, to keep power in white hands, safe from the so-called ‘Swart Gevaar’ (‘Black Danger’): second, and perhaps more significantly, because it is so often ignored, and because it is so post-modern, its concern with cultural autonomy and integrity; a concern for self-determination. This impulse arose from the successive Boer experiences under British imperialism. History works in cunning ways. Apartheid, for all its negativity, swam against the liberal stream. At the same moment that Apartheid died, liberalism has come to be condemned for its cultural imperialism, or as Highwater (1981) puts it, a ‘self-serving fallacy’. Perhaps, it is significant that with the decline of Apartheid the liberal phantasm declines also? As Chabal (1997) states:

We. Them. ‘We can’t impose our values on them’. The great racist lie at the centre of Western liberalism. The great sophisticated lie which in the century ahead will kill, maim, starve, rob and beat to death tens of millions more Africans than the primitive little lies of Afrikaners ever did.

The Boers’ suspicion of British Imperialism was based in the threat to their integrity made by successive British administrators’ attempts to anglicise them. This experience left an indelible mark on the psyche of the Afrikaners. They were sensitive to the implications of cultural imperialism as they too lived on the frontier. On many other frontiers the settlers solved this problem by a holocaust of extermination, tempered with restricting native peoples to reservations. This is well exemplified by the following dialogue between the Boer Cilliers (Siljay) and the Barolong Chiefs from Sol Plaatje’s 1930 epic, ‘Mhudi’ (1957).

‘But,’ asked Chief Moroka, ‘could you not worship God on the South of the Orange River?’

‘We could,’ replied Siljay, ‘but oppression is not conducive to piety. We are after freedom. The English laws of the Cape are not fair to us’.

‘We Barolong have always heard that since David and Solomon, no king has ruled so justly as King George of England’.

‘It may be so,’ replied the Boer leader, ‘but there are always two points of view. The point of view of the ruler is not always the view point of the ruled. We Boers are tired of foreign Kings and rulers. We only want one ruler and that is God, our creator. No man or woman can rule another’.

‘Yours must be a very strange people,’ said several chiefs simultaneously (1957: 82-83).

The Boer, Siljay, aptly expresses a complex question of the right of people to their own values and world views in the face of a dominating power. It is a question that is so contemporary in this globalising world. Yet he was speaking more than 150 years ago.

Tribal frontier

The new South Africa’s policy, in an attempt to be the most ‘progressive’, has embraced an ideology of modernism, and acted somewhat blindly to the advantages of harmonising with the traditional sectors as they too develop. Lately this has been acknowledged and processes have been set in place to acknowledge the role that traditional structures can play. However, the mistrust of tradition and custom by the ideologues still lingers and hinders the full participation of such sectors or a serious attempt to come to terms with the issues involved.

Concomitantly there has been somewhat of a denial of the multiple perceptual universes that all people live in, and which are particularly complex in South Africa. People are trying to live by both modernity and tribality while denying the one when in the other, and too often compromising the one for the other. To some extent, people ‘accept’ the requirements of modernity, while secretly paying homage to ‘tribality’ and adhering to its customs and practices whenever summoned to do so.

The Limpopo Province of South Africa is particularly interesting as a case study since it is one of the most culturally complex Provinces in South Africa. Limpopo has three dominant ethnic/tribal groupings dominating vast swathes of the province, each with their own internal divisions; the Venda, Northern Sotho and the Shangaans. In addition there are the Ndebele who are less populous yet the most widely distributed throughout the Province, Indian South Africans, Zimbabweans, Motswanas, Mozambicans, a smattering of white South Africans and recent migrants from all over Africa and the world.

In 1996 a list of issues of concern in public management was presented to the Provincial Government’s Human Resources Committee. One of the issues highlighted was ‘the conflict between the demands of custom and tradition and the demands of modern work’. No one on the committee denied the veracity and importance of the issue, but it was taken off the list of issues to be presented to the Provincial Cabinet, because it was seen as embarrassing. Yet the very same person, who censored the list, had adamantly confirmed that even for someone as ‘modern’ as himself, such summonses were ‘non-negotiable’.

The embarrassment of the emerging middle class at their multiple allegiances and their conflictual dominant frame of reference all too often means that there is a lack of action and dialogue toward finding an appropriate way to deal with this dilemma. This further contributes to the confusion of the issues involved and processes affected. In a context in which people desperately want to show that they can function in a bureaucratic society of mediated consumption (after Lefebvre’s 1976 notion of a Bureaucratic Society of controlled consumption), people do not want to acknowledge that they are tribal at heart. If denial or rejection continues we will all face the uncertain yet inevitable consequences. The possibility of conflict between globalisation and a vast number of particularities could unfold. Shane (2006: 4) notes that terrorism, rather than being global has a ‘provincial soul’. War on too many fronts is always dangerous. Inayatullah (2000: 816) argues for this recognition as follows:

What I argue for is a layered self, which does not discount ego, family, nation, religion, race or ideology but progressively moves through these various aspects of identity, until humanity is embraced, and then finally a neo-humanist self, wherein nature and the spiritual are included. Identity thus has depth but is not shaped by the dogmas of the past.

But this has to happen in a way determined by the people of the particularity. She continues to warn of the serious consequences that could arise from this frustration of a people’s right to self-determination:

If we do not go this way then the long-term result will be depression. … By the year 2020, non-communicable diseases such as depression and heart disease are expected to account for seven out of every ten deaths in the developing regions, compared with less than half today. Death becomes the future since hope is lost.

The real danger is that we will continue creating conflict between particularities and modernity, fuelling the dangerous dynamic in world affairs signalled by 9/11 and the increasingly uncertain global environment. Yes it may be reactionary, but it has to be recognised as an honest reaction to a globalisation which is primarily concerned with seducing the elites of the particularities. The world is in danger of warring about cultural diversity on a number of different fronts for the foreseeable future. A modus operandi needs to be found that can harmonise this diversity and pacify and allay potentially destructive forces. Traditional society promises to hinder development, unless some way is found to harness the energy released by ‘tribality’ and its values. In turn these particularities can temper and enrich the process of globalisation, harnessing it for the cultural integrity of the particularity, keeping faith to the basic values and spirit of that particularity, while adapting to the changed historical circumstances. The debacle in Iraq serves as a warning to those who would tamper with seemingly weaker traditional forces.

This is both a challenge and an opportunity. Can a dialogue on culture and management be incubated? The Afrocentrism debate seems to be one part of such a conversation, which could only release creative energies and perhaps do more to reduce terrorism than anything else.

Instead of seeing ‘tribality’, particular traditional societies, indigenous knowledge, values etc. as reactionary or, at least, simply resistant to change, they should be approached with respect, sensitivity and circumspection. There is an urgent need to confront this issue and nurture conversations in all the particularities towards taking ownership of development in the face of a rampant globalisation. In other words, particularities need to guide and decide on the direction of their particular development trajectory, i.e., self-determination. A first step is to bring the issues into the open. At all the frontiers, conversations need to find ways to harmonise the diversity, not just manage or attempt to merely co-opt it.

Confronting tribality

Stated in the starkest possible way, and with some obvious caveats, my concern is with the inescapable fact that the West seems today no nearer to understanding Africa than it was a hundred years ago, on the dawn of the colonial enterprise (Chabal 1997).

A voyage of discovery

I am an African, of Ashkenazi Jewish cultural origins whose grandparents came from near Vilnius in present-day Lithuania, arriving in the Cape Colony in the 1890s, with whatever cultural roots and/or ‘hybridisations’ that lie unknown back in the mists of time. I grew up in the privileged upper middle class of modern Johannesburg of the 1950s and 1960s. Johannesburg was the frontier of the world mining industry, a typical mining town. It grew very rapidly into a cosmopolitan city with all the accoutrements of modernity. Johannesburg under the rise of formal Apartheid, and despite it, was a very vibrant place. Sophiatown and Alexandra were centres of this vibrant emerging urban community, and its Great White Way on Commissioner Street boasted theatres to match anything around Times Square in New York City or London. Art Deco and later Bauhaus left still visible marks on the city’s landscape.

Johannesburg, and other South African cities, are characterised by a mix of many cultures even if dominated by the modernizing urban culture. European and American fashion and music mixed with the indigenous strains through Mbaklanga, Kwela, township Jazz and now kwaito. In the late 1950s and early 1960s the streets were alive with music. Kwela bands roamed Johannesburg performing guerrilla style in the streets with people throwing coins in their caps on the pavement in appreciation. A tea box bass, two or three penny whistlers and a guitarist, would break and run when the police arrived as they routinely did.

Safely walking these streets as a child was an exciting adventure, despite the clouds of Apartheid hanging over it. The Apartheid regime wiped out Sophiatown and tried to empty Alexandra unsuccessfully.

The rural hinterland was ever present in the dress, languages and style of the people. But the rural context was somewhat mysterious to a young white boy growing up. Like another world, that intruded into my everyday life in almost every way, but remained afar. I would travel through rural South Africa and Rhodesia (as Zimbabwe was called in those days), seeing the traditional grass and mud huts, mingling with the people, immersed in differences and similarities I did not understand but felt and perceived.

I spent 12 years studying and working in the United States and Canada, and in all that time I never felt truly at home; ‘home’ was always calling. It was only years later that I realized that I, too, had been a migrant per se. I returned to South Africa in 1982 believing change was more possible. It had become apparent to me that the only solution for the Nationalist Government, the African liberation movements and the Captains of Industry, was some sort of negotiated resolution. However, I was greeted in South Africa not by vibrant analysis of the possibilities for South Africa but rather by a growing hegemony of thought, soon to be spearheaded by the campaign to make the country ungovernable and the widespread school boycotts. Instead of vibrant analysis one was met with calls for solidarity, and intellectuality was reduced to mobilizing slogans.

It was very different to the lively climate of disciplined theoretical and policy debate that had so characterised the period of Biko and others that had been so influential in the 1960s South Africa I had left. In the South Africa of the 1980s one was even castigated as a reactionary for suggesting that negotiations were even a possibility, let alone inevitable. It seemed that people were so caught up with actions and events, and in the rush to identify with the ANC and UDF, that they could no longer discern trends. Discussion and dialogue had become narrow and confined to the politically correct, on the left at least. Freethinking was no longer encouraged.

Reflecting on this now one is awed by the fact that a little over twenty years later the rule of ‘political correctness’ is incarcerating debate and conversation on a world-wide basis. Perhaps South Africa, one of the models of ‘regime change’, was a pivot around which the whole world was changing from a cold war dialogue between Communism and Capitalism to the ‘War on Terror’.

Around 1984, in an informal seminar at a prestigious South African university, a paper was presented concerning research conducted with migrant labourers in Johannesburg. The author had found that to the migrants ‘home’ was not Johannesburg where these migrants spent the overwhelming majority of their time and where they earned a living, but rather, ‘home’ was the village from which they originated and where their ancestors were buried, that is, their traditional frame of reference. A discussion broke out between two distinguished professors who were present as to ‘Why “these people” relate to the “homelands”?’ It was pointed out by someone that it was not the Apartheid homeland the migrants were referring to but their spiritual ‘home’. People get their ontological security from their spiritual relatedness to their ancestors, through traditions, customs and communing with the spirits as a community. One of the professors inquired, rather condescendingly, ‘but why do these people need spirit?’ Someone replied, ‘If you don’t know I can’t tell you!’ This awakened me to the fact that many modernists, although highly educated, had difficulty accepting the world view of the other.

I worked for 10 years at the National Institute for Personnel Research (NIPR) which was incorporated into the Human Sciences Research Council in 1986. During this period I had the opportunity to conduct Human Relations Climate Investigations in Public, Private and Civil Sector organisations during a period of rapid social change. My work was not limited to organisational investigations but was also directed at broad policy issues in a variety of sectors and disciplines.

In 1992 I was headhunted to the University of the North in Limpopo Province and have worked there ever since, through its merger with the Medical University of Southern Africa to become the University of Limpopo. Only when I moved to Limpopo was I confronted directly by tribality. It took quite a while before I began to come to grips with the social dynamics. They were so different to what my anti- Apartheid ideas and urban prejudices had led me to expect. The left wing urban ideology of the time had no place for tribalism and ethnicity. These were judged merely as products of Apartheid. The reality I found forced a very difficult and painful reappraisal of these ‘truths’. As Dean, Executive Dean and then Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Campus Principal at the University of Limpopo’s Turfloop Campus (previously University of the North) I have through participant observation and focused research been able to explore the implications of the rural context on management processes.

The Apartheid Legacy

At the inauguration of Mr. Mandela as the Chancellor of the University of the North in 1993, a Venda chief sent the ‘Tshikona’, (the Venda Men’s Dance), performed when the community celebrates rights of passage rituals, to perform in honour of the occasion. It was a great honour for President Mandela. The dance involved at least a hundred male dancers of all ages, moving as one snake to wondrous music from their simple pipe flutes to the beat and rhythm of the Dumbula, the massive Venda sacred drum. It was a marvel to behold for it so completely integrated anarchy with order. While the dance was continuing on the field in front of the stands, a student leader attempted to take the microphone so as to call the dancers to end. Mr. Mandela was moved to intervene and had to tell the student leader to desist. To the student leaders this was something to be tolerated and its meaning and beauty were somehow lost on them, though not on the vast majority of students, visitors and dignitaries gathered there who watched in awe, clearly moved by the spirit of the dance. There is a strong tradition among African intellectuals of distancing themselves from their traditional roots, at least in their writing.

In the 1960s and 1970s young Black Consciousness intellectuals consistently spoke against their traditional cultures and traditions. This political imperative was clearly expressed, for example, in the early work of Prof. Njabulo Ndebele, now the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cape Town. He wrote in the early 1970s:

… the blacks must set about destroying the old and static customs and traditions that have over the past decades made Africa the world’s human zoo and museum of human evolution. When customs no longer cater for the proper development of adequate human expression, they should be removed. Almost all the so-called tribal customs must be destroyed, because they cannot even do so little as to help the black man get food (1973: 81).

The problem with cultures is the unassailable fact that you cannot understand them fully, as an outsider. It was widely held that local ethnicity and culture were creations of the Apartheid state and that when Apartheid went so would any talk of these ‘survivals’. This reflects the a-historical view which has so dominated academic debate in South Africa, a perspective that believes that people want to leave their traditional roots behind for ‘development’ or modernity.

However, sentiments have changed since Ndebele made this reflection of a particular moment in the history of the struggle. Mafeje (1996: 20) identified the negative effect of such thinking among African intellectuals and others as:

… to devalue traditional institutions in Africa and elsewhere in the Third World and to give the impression that ‘modernisation’ was necessarily a reproduction of European institutions in Third World countries. The latter assumption has proved unwarranted …

Things have now changed as Wole Akande (2002) concurs:

In the fifties and sixties, the peoples of the newly independent African countries were told Western values would inspire modernization and lead oppressed people to demand the human rights enjoyed by people in the Western World. Today Africans find it ironic that the values broadcasted from the West represent oppression of the poor and the decay of civilization. Consequently, Western values are fast becoming discredited and devalued in the eyes of many Africans.

As I (1984: 1) previously wrote:

The racial dimension has been so overemphasised that it makes any discussion of cultural differences, within this context, appear as a justification for the policies of Apartheid. Without negating the basic similarities between all human beings there is still a need to come to terms with the various aspirational paradigms of our varied peoples.

However, at the time, this was deemed ‘politically incorrect’. Dialogue in South Africa has been dominated, distorted, dissuaded and outlawed by the repressive Apartheid state’s rigid censorship, bannings, pass laws, forced removals, detentions, and violence. On the other hand, in progressive circles, ‘political correctness’ in the service of ‘solidarity in struggle’, sometimes distorted and dissuaded dialogue as well. In the words of Howe (1993: 4) ‘Apartheid has given ethnicity a bad name’. In April of 1993 scholars from all disciplines and all corners of the world gathered in Grahamstown for a conference called ‘Ethnicity, identity and nationalism in South Africa: Comparative perspectives’. McAllister, one of the convenors, noted:

Just a few years ago it would have been impossible to hold a conference of this kind in South Africa, or even to address the kinds of questions and issues which it raised. Not only was there a boycott which prevented intellectuals from other countries from visiting our shores, but within South Africa itself the feeling was that ethnicity was purely a creation of the Apartheid state.

Furthermore, as he clarifies, ‘To discuss ethnicity was somehow to legitimate its existence, and thus to legitimate the Apartheid state. There are still South Africans who feel this way, but the tide has turned’ (1993: 7).

Hopeful words, but unfortunately the issue of culture, Afrocentric management included, is still something that is difficult to discuss without raising emotions and memories of the vicious social engineering of ethnicity under Apartheid.

The view from the tribal frontier

The view from the tribal frontier is very different to the view from the heart of modernity, be it Johannesburg or any other capital anywhere in the world where modernity is dominant. In Limpopo and other parts of the rural Southern African subcontinent, ‘tribality’ is the dominant. Even the Afrikaners see themselves as a tribe. At this frontier of tribality, the modern is only emerging, somewhat dominating only in urban or peri-urban nodes against a complex tribal backdrop. This is very different to viewing the tribal against the overwhelming backdrop of New York, London, Moscow, Beijing, Amsterdam or even Johannesburg, Durban or Cape Town.

This difference of perspective is common to all situations in which what Baudrillard (1995) calls ‘particularities’, are in contact with the modernising impulse called globalisation, or what has been called the new imperialism (Escobar 2001). There is also a frontier in the midst of the centres of modernity with the hoards of immigrants who arrived during the latter half of the last century and who are still arriving. That is a frontier too, but somewhat blurred by the political correctness of notions of melting pots and hybridisation which have so dominated the imagination until recently. It was presumed, and hardly questioned, that the immigrants were being transformed into citizens, almost totally absorbing the dominant culture as their own. The jury is still out on this question. It was certainly given a jolt by the fact that the London suicide bombers were British born in most cases. Perhaps, many of the new immigrants to the first world are only role-playing the ways and means of their new host country, while maintaining their own historico-cultural-spiritual roots and identity.

One of the key concepts in traditional society is the ‘ancestors’. In the West one can ask the question, ‘Do you believe in the spirit of the ancestors as a guiding force in everyday life?’ as a somewhat abstract question, assuming that one may or may not believe. In other words it assumes that there is a choice for an ‘individual’. To someone immersed in traditional society from birth, the ancestors are a given that people accept unstintingly. The question of whether or not one believes in the ancestors is nonsensical in this context. There is no question. This is, perhaps, what makes it embarrassing to admit. What will the Western other think of me? It is safer to deny it.

The ancestors are so intertwined with so many aspects of the persons being, at a totally assumptive level, it may not even be possible to, in fact, reject, as it may be in the West, the primary difference being that all people become ancestors when they die. In a sense, immortality lies ahead of everyone. Judeo-Christians do not become gods. Chief Seattle, beginning his 1854 Oration put this difference of perspective and values very elegantly:

Your dead cease to love you and the land of their nativity as soon as they pass the portals of the tomb and wander away beyond the stars. They are soon forgotten and never return. Our dead never forget this beautiful world that gave them being. They still love its verdant valleys, its murmuring rivers, its magnificent mountains, sequestered vales and verdant lined lakes and bays, and ever yearn in tender fond affection over the lonely hearted living, and often return from the happy hunting ground to visit, guide, console, and comfort them.

He concludes: ‘Let him be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not powerless. Dead, did I say? There is no death, only a change of worlds’ (Oration of 1854: verse 1). Tribal people are not merely exotic remnants of a dead age, ‘noble savages’ as it were, but real human beings living now. As Inayatullah militates:

As American Indians have told New Age appropriators, if you desire to use our symbols, our names, our dances, our mysticism, then you must as well participate in our pain, in our defeats, in our anguish. You must also see us in our humanity, good and evil, and not as noble savages. It is the arbitrary exclusion of certain dimensions of history and self that become problematic (1999: 816).

Immortality is hard to give up. People relinquish the histories passed down to them only very reluctantly. Identity is rooted in history and culture, and is not simply an outcome of the environment. In a world where the particular is dominant, it is foolish to deny it and even more foolish to ignore it. One cannot assume that all people really want to embrace modernity uncritically. The resistance coming from particularities cannot be disregarded as mere resistance to change, for it draws from the wisdom that has been handed down through the ages. People recognise their particular culture, tradition and history as their birthright.

It is worth noting the seminal founding work of political anthropology, Pierre Clastres’ ‘La société contre l’état’ (1974) published in English as ‘Society against the State’ (1989). He points to the, albeit unconscious, ethnocentric judgments made of primitive societies, ‘… their existence continues to suffer the painful experience of a lack – the lack of a state – which, try as they may, they will never make up’ (189). He contends that this ethnocentrism has an ‘… other face, the complementary conviction that history is a one-way progression, that every society is condemned to pass through the stages which lead from savagery to civilization’ (190). He concludes his argument as follows: ‘It might be said, with at least as much truthfulness, that the history of peoples without history is the history of their struggle against the state’ (218).

The attempt at hegemony by the state unites but, at the same time, also destroys the dialects, cultures and languages that do not gain dominance. This homogenisation is resisted by particularities to various degrees. How many dialects and languages has the world lost already? Perhaps we will never know. Griggs and Hocknell (2005) estimate that what they call the ‘Fourth World’ consists of between 6,000 and 9,000 particularities and accounts for more than a third of the total population of the world. The implication of all of this for the case of management in Africa and other regions with vibrant particularities with a strong allegiance to traditional societies is that they ‘conspire’ against developments if they perceive them to threaten the core spirit of their traditions, customs, land and autonomy. People accept change which they perceive as beneficial. One must never presume ignorance and any lack of intelligence among people from particularities, or tribals, because of their lack of formal education. Rural people are very clever and can very quickly identify the weak points of any system and abuse, exploit, corrupt or deflect it. The ignorance and blindness of the so-called ‘educated’ may even be much greater. Andre Gide who took a trip down the Congo in 1925 wrote in 1927:

But people are always talking of the Negro’s stupidity. As for his own want of comprehension, how should the white man be conscious of it? I do not want to make the black more intelligent than he is, but his stupidity, if it exists, is only natural, like in animal’s, whereas the white man’s, as regards the black, has something monstrous about it, by very reason of his superiority (124).

Gide’s observation unfortunately still captures the way the Globalisers still look at the particularities. The world is still suffering from these self serving misperceptions and misconceptions.

Identity and migration

There is a growing awareness of the difference between the migration of Europeans and even Eastern Europeans and Jews to the United States of America prior to Second World War. These immigrants sought after the American Dream and, while in fact maintaining an identity from the home country, quickly integrated into the culture of their adopted home. However, the newer waves of immigrants are perhaps different both in their origins outside of the common European culture of previous waves of immigrants, but also in their strong ties to the culture of their particularity. A recent article in Pravda highlights a particularly radical perspective on these recent immigrant waves to the United States and Europe. Mikheev (2006) puts it succinctly: ‘The world which the West has been ruthlessly transforming for years, has started to transform the West in return’. He continues to explain:

Many respectable politicians acknowledge nowadays that massive immigration may destroy the Western civilization in the end. Immigrants continue to conquer the world promoting their own needs and values. … As a rule, immigrants preserve their national identity, which gives them a reason to defend their rights and needs. … Immigration has become a serious problem for the USA too. Non-white Americans have become much more socially and politically active than they used to be in the past. There are US experts who think that immigrants and their growing families will eventually create one of the most serious problems for the USA’s internal security in the 21st century. This view was recently echoed by the Republican Senator for Tennessee in the United States, Lamar Alexander, who said: ‘A lot of the uneasiness and emotion over this immigration debate is from Americans who are afraid we are going to change the character of our country’ (Reynolds 2006).

While the Democratic Senator from California, Dianne Feinstein, commenting on the legislation making English the official language of the USA, put it slightly differently:

I think it’s very important that people who want to spend the rest of their lives in this country become identified with American ideals … It’s important people learn to speak the language, learn to respect the democracy, want to abide by the rule of law and that this country shouldn’t be little ghettos. Learning English is symbolic of buying into that ideal (Reynolds 2006).

This recognition of the fact that migrants may not take on the culture of the host country as their own through assimilation or integration is dawning all across the developed world. Commenting on the Danish experience, Toksvig (2006: 23) writes:

What seems to have surprised Denmark is that many of the people arriving in need of relief wanted to bring their own culture. They did not want to be Danish in the way the Danes did. Even today it is estimated that, instead of assimilating, 95 per cent of thirdgeneration Turkish-Danish males import their spouses from Turkey.

The colonial powers did not consider their settlers taking on the cultures of the countries they occupied; after all, they had invaded. So why should immigrants assimilate? Or rather, why should their adherence to their home culture surprise the Europeans and Americans as it seems to? Some migrants may try and divide their worlds, holding traditional society as some kind of static entity which they like to visit in order to show the people, from the village, how successful they have become. But most have no choice but, to some degree at least, to accede to custom and tradition’s demands as they intrude into their everyday life. Demands such as being summoned to the village for funerals, weddings and other community rituals are generally not negotiable. Other demands, such as those for support of extended family members or the requirement to fund ostentatious funerals and weddings may drive the person to any lengths to satisfy these demands and requirements, so as not to lose face.

This is not to say that traditional societies, as such, are unchanging. They are changing with time and context like everything else. The question is whether the particularity is going to be able to protect values and customs dear to their hearts, and play the role they should in guiding the conversation towards a future modus operandi maintaining the integrity of their history and values. Perhaps this will lead to a range of ‘hybrids’ for this southern tip of Africa. Maybe something else will emerge through a blossoming of diversity and mutual respect. Or is something to be imposed?

It is, of course, always difficult to understand what is happening in other parts of the world, as it is to understand why it is that ‘others’ do not behave as we would expect them to do. Nevertheless, our deficiencies in making sense of what is taking place in Africa seem to me to go far beyond the usual problems which we may justifiably have about understanding other peoples and continents. What is puzzling to me is not just that our failure to comprehend Africa is extraordinarily acute but that, in this age of supposed rationality, we seem content to accept failure on such a scale when it comes to the African continent – as though the curse of the Dark Continent should forever obscure our vision and impair our ability to understand (Chabal 1997).

On the other hand those living in the First World view traditional society from a dominating perspective, considering traditional cultures as simply remnants of a distant past, as survivals. This arrogance of domination, presumed superiority, risks trivializing these cultures as quaint and interesting, and not really taking them seriously. Some even attempt to adopt a co-optive paternalism. That is, ‘simulating’ an accommodation through the adoption of the symbols and trappings of the particular cultures. This unfortunately leads to the marginalisation and denial of the more profound questions being asked by the leaders of particularities worldwide. This only serves to drive them to more covert levels. Espey (2002), while categorically emphasizing that he does not promote this, notes:

… There is no doubt that poverty in the south and the clash between the dominant Western civilisation and other subservient civilisations is fertile breeding ground for global terrorism. This is a security issue for the north and is already being acknowledged by leaders in the north (in Macfarlane 2002).

Much of the third world, in contact with modernity, either at home or abroad, has, perhaps, been operating at this covert level over the past century, living in their multiple worlds and keeping their true identity within their community. Unlike Third Worlders (i.e., those from particularities) or is it Fourth Worlders, First Worlders, the moderns and post-moderns as they like to term themselves, have a notion of an integrated unified identity striving for self-actualisation, which to a Third Worlder looks a lot like self-indulgence. This hyper-individualism is hard for most Third Worlders to understand. Etzioni comments on a 1993 meeting of Asian leaders in Bangkok:

The purpose of the meeting was to formulate an Asian stance on human rights which would be represented at the upcoming World Conference on Human Rights. According to one report, ‘What surprised many observers … was the bold opposition to universal human rights … made on the grounds that human rights as such do not accord with “Asian values”’. Asian intellectuals justify this opposition on the grounds that Western notions of human rights are founded on the idea of personal autonomy, which Asian culture does not hold as a fundamental virtue, if it embraces autonomy as a virtue at all (1997: 179).

Third Worlders on the other hand are used to living in many very different cultures and are comfortable in each of them, or at least can appear to be. What is masquerade and what is real only the actor may know, but possibly only viscerally, in many cases. Migrants learn quickly to move seamlessly between their worlds without any inner contradiction.

Cornejo Polar (2000) counters notions of hybridity with the notion of cultural heterogeneity. Grandis and Bernd (2000) summarise Polar’s view as follows:

Rejecting the belief that migration results in a synthesis of the urban with the rural, and the present with the past in the identity of the immigrant, he asserts that migration leads to the formation of dual, or multiple identities. Although these often appear to oppose one another, they are able to coexist without tension in the migrant, and allow the articulation of multiple and apparently contradictory perspectives in the discourse of the migrant (2000: xx).

This concurs with research conducted among migrants in Limpopo Province (Franks 1994) which found that the migrant’s world is one in which it makes sense for him/her to live and work in Johannesburg, while ensuring the survival of ‘home’. Above all, ‘home’ remains the migrant’s primary source of identity while s/he can move easily between these worlds.

To someone who does not know of the subtle varieties of world views that are possible, isolated in their narrow confines (albeit hypermodern or post-modern), it is difficult to understand the sensibilities of the other as anything but frivolous. They are clearly foreign. Middle class urbanites of our global cities cannot even move among the denizens of their own cities without culture shock, let alone understand the sensibilities of a sangoma.[ii] in South Africa. This inability to understand the legitimacy of the other, no matter how strange and foreign they may appear is the root danger of the present crisis in world affairs. It is not that traditional cultures are unchanging. As Garcia Canclini (1995: 155) proposes:

… What can no longer be said is that the tendency of modernization is simply to promote the disappearance of traditional cultures. The problem, then cannot be reduced to one of conserving and rescuing supposedly unchanged traditions. It is a question of asking ourselves how they are being transformed and how they interact with the forces of modernity.

Viewing issues of management from this perspective does not accept the superiority of modernity in its assumptions but rather resents its seemingly inevitable domination. As we see, the resistance to this domination in Iraq, and throughout the Middle East, has resorted to open terrorism and guerrilla warfare. Perhaps, this will force a realization that the voices of the particularities demand recognition and respect, and demand that their concerns are addressed. Their capitulation cannot be forced without their annihilation. Luyckx (1999: 979) reports the plea of one of the non-Western participants at the Brussels Seminar in 1998, as follows:

There is already a dialogue and cross-fertilization going on between Asian cultures and Western culture. The same thing is true for the historic role of Islam. But we are urging the West to change, and go into a real dialogue. There is no shortage of noisy words in the field of management (Mintzberg 1999).

Reality is far too complex for these buzzwords to be more than very partial analyses, no matter how holistic they claim to be. Here one must remember the caution of Schopenhauer against the professors and their ‘… fiction of a reason that knows, perceives, and apprehends immediately and absolutely’ (1966:xxvi).

In the investigation of social situations, that is, in trying to grapple with understanding the complex dynamics of situations, contexts and people, there is great danger in the application of predetermined understandings. The error of such applications is systematic. This systematic error may, down the line, create more problems than the initial intervention was intended to solve.

Humankind will always (continuously and forever) have to find appropriate ways to manage in the ever-changing situations and contexts and with the people whose interests and concerns are diverse and also always changing. All the models and buzzwords have something to teach us, but in the particular moment in a particular situation, with particular people, the appropriate thing to do cannot be predetermined. It is always a matter of fit, in terms of time and space, yet there is seldom an abstract fit; it always involves judgement. However, this is not to belittle the importance of models and ‘loud words’ in enriching management and leadership vision and understanding. There is always a need for praxis and knowing one’s context and people.

The danger of ‘error’ in all theories and models is that it is systematic. Error systematically fetishises one aspect of a complex and dynamic situation, ignoring others. Following Schopenhauer (1844) and Baudrillard’s (1983) notion of the ‘precession of the model’, Giri (1998) draws upon the Upanishads:

Let us begin with the Upanishadic insights where it is believed that reality is beyond our categorical formulation and comprehension. Whatever categories and concepts we use to make sense of reality, they are not adequate to provide us with a total picture. The Upanishadic insights refer to the simultaneous need for concept formation as well as the abandonment of concepts. … It is only when one fully and thoroughly disengages oneself from superimposition, that one opens oneself to an experience of reality.

A strategy may be appropriate in the abstract but may not be appropriate in the particular moment in a particular situation in the particular context with those particular people.

For example, after the changes in South Africa, the application of participation as a panacea, as a visible sign of the new democracy, had a particularly detrimental effect on the running of the very institutions that the country needed in order to build itself for example. In Higher Education, where I have been an active participant, it certainly contributed to the ungovernability which characterized the sector, especially the historically Disadvantaged Institutions, for many years. Leadership was cowed before an orgy of participation, and corruption of all sorts followed. This is still continuing. Participation, when introduced into a very volatile and politicised situation ends up allowing the domination of any organised minority. Participation, too, has to be managed. The challenge is to find the appropriate way to manage in particular situations with particular mixes of people and values, in full awareness of the nuances of the particular moment in time. We need to learn how best to manage in our particularity.

Culture and Management

A Saudi Arabian public manager’s resort to disciplinary measures to control his subordinates’ performance and behaviour is severely restricted by the civil service code and the strong traditional inhibition on causing someone to lose his face or means of livelihood. Consequently, he is obliged to try informal methods of persuasion and social pressures before turning to punitive steps. In assuming the role of the paternalistic leader, the manager is expected to look after the financial, social and professional welfare of his subordinates who will return this in the form of personal loyalty, obedience and acceptable standards of behaviour and performance (Atiyyah 1999: 9).

The Saudi public servant, as with his South African counterpart, is forced into roles that a global manager would consider an abuse of his/her freedom. How would these same global managers respond to the KwaZulu Provincial Minister of Education’s refusal to be in her office for three weeks because her office was bewitched? As her husband told the media, ‘There is a common belief that she is being bewitched by her predecessor’. The predecessor responded: ‘I don’t know anything about muti. I am a Christian. I don’t want evil to affect anyone’. The culture of the context infiltrates every organisation or institution to some degree. For instance, the old school tie, Broederbond, Lodges, etc., can all influence organisational functioning. This is no better or worse, only different, in its extent and domination. On the tribal frontier traditional culture dominates in fact.

Ouchi (1981: 40) noted the crucial point when he wrote that ‘… an organization cannot convert new employees into a firm specific culture deviant from the surrounding society – so instead it adopts an organisational culture with central values identical to those of the surrounding society’. Sinha (1992: 5) reported on this situation in the Indian sub-continent, which harbours so many ancient particularities:

Other scholars (e.g., Ganesh 1982; J.B.P. Sinha 1990) confirmed that Indian work organisations remain embedded in the socio-cultural milieu. Modern technology is often compromised with social compulsions to the extent that in some cases automatic machines and plans are rendered manual (either by neglect or inept handling) for creating more job points. Work forms remain Western in description, but work relationships are permeated with cultural ethos. The organisational chart as given by the supplier is kept neatly in the drawer, but hierarchy is culturally shaped. The organisation may have high tech but the identity remains social (Parikh 1979). Ganesh (1982: 5) observed that ‘… organisations in this country [India] have fuzzy boundaries. Essentially organisations have come to represent settings in which societal forces interact. Thus, our organisations have provided settings for interaction of familiar forces, interest groups, caste conflicts, regional and linguistic groups, class conflicts, and political and religious forces …’. He further pointed out: ‘In some cases, the sociocultural factors adversely affect organisational vitality and productivity. However, in some other cases, they are effectively utilized to maintain high productivity (J.B.P. Sinha 1990; J.B.P. Sinha and D. Sinha 1990).

More recently Kao, Sinha and Sek-Hong (1995), published an important work, Effective organisations and social values, which was succinctly reviewed by Professor Gandhi of the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore, expanding on Ouchi’s basic premise as follows:

People’s behaviour in different social settings, whether at home or at work is largely determined by their values, attitudes and beliefs. To a large extent the culture one belongs to determines these. In organisations people belonging to the same culture have similar social values and therefore display similar patterns of behaviour. Managers who recognise these social values and design appropriate work systems tend to create more effective and successful organisations.

Instead of functioning as the global manager would expect, decisions in the organisation are overridden by interests outside the organisation. A chance meeting at a funeral can undo all the plans made by an organisation in its planning. Decisions can be made by the collective behind the scenes.

Sinha provides the key to sustainable development, through harmonising the cultural nuances of the social context with the needs of the organisation. Rather than attempting to co-opt, suppress or merely wish them away, the customs and traditions of the cultural particularity have to be negotiated if sustainable development is to be arrived As Mazrui (1974: 17) has pointed out, the failures of African Governments perhaps follow from a dependent stratification system, in which the selection of leaders and the conferring of privilege are ‘based on values and skills drawn from a dominant foreign source’. They have been those most Westernised, and not those with the vision and capability to develop their historical context. In a sense what Mazrui is alluding to is the fact that African development has followed a Western rather than an African template, a template foreign to the third world context and therefore an imposition. Afrocentrism arises as a counter to the Eurocentrism that has dominated the world for so long. Afrocentrism arises from the interaction between the domination of the socalled global over the local, or what Baudrillard (1995) calls particularities. These notes from the frontier understand Afrocentrism as viewing the world from and within Africa.

Much of the management-in-Africa literature seems to focus on how one should motivate and manage people, relying heavily on notions of participation which is where first world management happens also to be, the learning institution etc. However, until we face the deeper issues of values and identity, honestly and openly, we are not going to find an appropriate modus operandi for management in Africa or any other particularity.

Even champions of globalization increasingly fret that it may damage or destroy the diversity that makes the human race so fascinating, leaving nothing but homogenized, least-common-denominator forms of creativity. In the wake of September 11, there is a new urgency to these concerns. The fury of the terrorists – and of the alarming number of people around the world who viewed the attacks as a deserved comeuppance for an arrogant, out-of-control superpower – is sparked in part by a sense that America is imposing its lifestyle on countries that don’t want it. And one needn’t condone mass murder to believe that a new world order that leaves every place on the globe looking like a California strip mall will make us all poorer (Weber 2002).

The view from the particularities is pretty unanimous. Sohail Inayatullah (2000: 12) suggests:

As the intelligentsia for hyper capitalism search for new legitimating factors, the challenge for the anti-systemic movements, in this possible window of opportunity, will be to create visions and practices of a more multicultural society with an alternative economics that is spiritually grounded.

Wole Akande (2002) echoes a similar sentiment:

But what is there to fill up the vacuum of decaying Western values? The expression ‘African values’, now typically propagated by Zimbabwean dictator Mugabe, is generally discredited as being the government propaganda of dictators. There is indeed a general confusion about which set of values might take the place of the once universal Western value set. However, the search for new or old values is ongoing. A search for historic, cultural roots can be observed in all non-Western societies. Predictably, any revivalist movement is bound to meet resistance especially since ‘Asian’, ‘African’ and ‘Muslim’ values have also been questioned as a result of their use of the most repressive parts of their cultural roots. Even so, the peoples of Africa nowadays act more self-confident on behalf of their roots than only a decade ago. Local cultural expressions, beginning with the arts, lead on a path towards cultural autonomy, which again should influence the value set.

On the other hand, all the talk of multiculturalism in the West risks becoming merely an exercise in containing particularities within modern and western constraints, all the time maligning the particularities. Just as the West uses extreme events to malign entire thousands-of-years-old cultures, this ‘hegemony of the new’ can have terrible consequences.

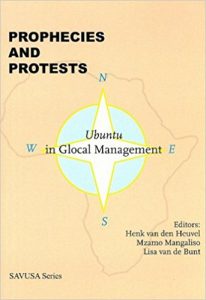

Many writers have contributed to an important dialogue towards ubuntu and African-based Management. Notable among them are Koopman (1991), Mbigi and Maree (1995), Boon (1996), Lessem (1996) and Mbigi (1997) among others (cf. as Mbigi (1997) describes in his book entitled ‘Ubuntu: The African Dream in Management’). While one appreciates their pioneering work one has to agree with Manning (2001: 3):

The first question, then, is how to bring in new thinking and at the same time preserve valuable experience. Secondly, how can the performance of new teams be enhanced? Answers to both questions are closer to hand than most managers think. They lie not in ill-defined notions of ‘African management’ or drawn-out diversity training, but in much more pragmatic ‘strategic conversation’.

One of the greatest problems with all the amelioratives (and Afrocentric management can be viewed as such, not that that is all it is) is that they have seldom been evaluated by neutral research. This does not have to be quantitative research, or what Mbigi denounces as ‘empirical research’. But, if others cannot confirm the claims, we are in the realms of ‘puff’. This goes for the legion of buzzwords that have each had their fifteen minutes of fame. One is reminded of Mintzberg’s question: ‘Are we so numbed by the hype of management that we accept such overstatement as normal?’ (Mintzberg 1999)

Thinking that ubuntu or some African or Afrocentric management can capture the essence of Africa is as absurd as thinking one could typify the West through its humanistic philosophies. These typifications are always limited to a few if not a single dimension of the issue. When used in that way these useful exercises become reduced to nothing more than buzzwords adding to the noise. It risks becoming the worst form of reification or rather commodification, more to do with commerce and business than with any real understanding of the complex dynamics faced at the frontiers. The question is whether it furthers our understanding and ability to find a way forward. However, despite these dangers, all buzzwords do have something to contribute to the conversation.

Issues of managing on a tribal frontier

Living and working on the tribal frontier in South Africa I can only attempt to draw on my research and management experience within this rural context to try and elucidate the issues that beg for understanding in terms of the issue of culture and management for a particularity in the face of rampant globalisation. The following anecdotes illustrate the general flavour of the issues unique to the tribal frontier:

A Director of a School appointed a woman lecturer as the supervisor of a student’s dissertation work. He was approached by a number of people to change the appointment because the student was a Venda male, and a ‘Venda male’ could not be supervised by a female. This is common to all the tribes in the Limpopo and beyond although it is slowly changing. Adherence to such views depends on the degree of urbanisation more than anything else. Perhaps, the lower the degree of formal education, the higher the so called chauvinism, at least publicly and by word, however,the deed may contradict this.

Rightly or wrongly the Director decided to accede to the request in this case. However, it illustrates the dilemma of offending local values or those of modernity in the attempt to find an accommodation which allows processes to continue. What if a white requested not to be supervised by a black. This we could not accede to as custom is not at issue, or is it?

Recently the Ministry of Education reported that its highly publicised programme to incentivise excellence in teaching had run into problems. The programme for bonuses was based on peer review scores given by colleagues. The minister of Education said the programme had run into problems because ‘they all just give each other 100 per cent’ (Hogarth 2006: 38). To which a local satirist, Hogarth, responded: ‘Gosh. What did she expect?’ (ibid.).

A Human Relations Climate Investigation conducted in the Limpopo Provincial Public Service (Franks, Glass, Craffert and de Jager 1996) indicated the following major issues:

– Lack of mobilisation of skills and expertise towards a common vision;

– Classism. A feeling among some public servants that they are ‘professionals’ and therefore superior to those they are supposed to serve;

– Confusion of political and administrative purposes;

– Historical and contemporaneous favouritisms (from baasskap to broerskap to sexism to comradeship);

– Inadequate performance evaluation systems;

– Inadequate supervision and management;

– Inadequate training and development;

– Covering-up, excusing, or simply just not recognising, incompetence;

– Conflict between the perceived demands of tradition and custom versus the demands of modern administration.

The core issue underlying all other issues and exacerbating the situation is what the authors termed ‘the conflict between the demands of custom and tradition and the demands of modern management’. The inadequacy of this conception is acknowledged, despite its descriptive accuracy and heuristic potential. It is important to understand that this conception represents a complex dynamic of interacting forces some of which have been sketched above.

To give an example: A public servant sits at a desk with a pile of work to do. S/he receives a phone call. It is someone from his/her village summonsing him or her ‘home’ for a funeral, marriage or other such responsibility. Culturally, and in terms of custom, this is ‘non-negotiable’, and takes precedence over any other responsibilities. Invariably the public servant puts his or her pen down, locks the office and goes ‘home’ for anything up to two weeks. The work must wait.

This is not something that can easily be changed. However, what can be done is to pro-actively put procedures in place for such an eventuality, whereby the public servant contacts someone else to take over the workload while s/he is away. S/he should brief the respective people as to what is to be done and what is urgent. In this way it would be ensured that work would at least continue and important things get done.

Unfortunately, at present we resist even acknowledging the issue. As a Chief Director said to me, ‘it is embarrassing!’ It is only embarrassing because we are trying to deny cultural differences, partly because Apartheid made such a fetish of them, and secondly because we are presently so concerned to prove we are modern.…

It is urgent that difference needs to be recognised and celebrated. It is certainly not something to be embarrassed about. Let us put appropriate procedures in place to handle these legitimate responsibilities. The conflict between the demands of custom and tradition and the demands of modern enterprise, overtly or covertly affects all work processes at each and every level of enterprise. For instance this conflict or dilemma:

– Affects all processes of selection, and placement of staff can be influenced by agendas extraneous to the goals of the organisation. Pressures to hire the home boy or girl is just the tip of this iceberg of nepotism;

– Work and modern enterprise are secondary to ‘home’ and all it stands for. That is, the spiritual frame of reference influenced by the ancestors, in the legends of the mass of the workforce;

– Interrupts work flows: funeral interruptions; absences without replacement, and/or delegation. In some cases access to the absentee’s office may not be possible and if faxes arrive there they will wait till the absentee returns. This has the effect of clogging work processes. Even high level executives have to attend numerous funerals on Saturdays disturbing their focus and limiting their work;

– Strengthens informal networks: encourages the formation of tribal, clan, political, or whatever based informal networks which compete with the formal decision-making processes. Because of this, partial interests tend to be served above those of the organisation as a whole. Generally it creates disruptive networks that exacerbate organisational politics hindering organizational functioning;

– Complicates discipline, and makes it impossible to implement performance management. Managers cannot act procedurally against a home boy or girl who is not performing without having to face his family and clan at the funeral every Saturday. It is not like in the city where, if a manager fires someone or disciplines them, the manager probably never sees the person again. In the rural context it is much more personal. Strategies and procedures need to be put in place that can help people face these very real and emotional processes, decisions and dilemmas;

– Encourages favouritism of all sorts: nepotism, clanism, tribalism and caraderie flourish. Hire the home boy or girl;

– Compromises security and confidentiality: the impossibility of implementing security protocols as they will be overridden for a ‘home-boy or girl’, or even a comrade.

Perhaps most important is the notion of ‘face’ affecting all processes. For instance it is never made apparent that an appointee is an affirmative action appointment because of the damage it would do to that person’s ‘face’ as such. Therefore no development processes are put into place to assist the appointee. Nor can such an appointee ask for assistance or mentoring lest they be seen as an affirmative appointee and lose face. These factors can end up subverting well-meaning processes such as affirmative action by reducing it to nepotism, ethnicism or tribalism, or just plain camaraderie among members of the ruling party. The strategy of favouritism has its downside, which only emerges in full strength once the third or fourth generation of affirmative appointments have settled in. What emerges is a struggle for positions and organisational politics rules supreme with merit being pushed aside. There is no reward for those who do their job, as they will not be noticed in the cocktail lounges in their expensive clothes or in their extravagant automobile nor in their mansion.

In addition the Public Service in South Africa is riddled with a confusion of political and administrative purposes. This can best be illustrated by looking at the hierarchy of trust found among the respondents in the Northern Province survey. The respondents were asked: ‘How well do you think the following people/organisations/departments can be trusted to look after your interests at work?’ The respondents could indicate ‘good’, ‘fair’, ‘bad’ or that they did not know. Generally the higher the education the less they trust any of the role-players. The current position clearly illuminates the morale situation in the Public Service.

It is not surprising to find that 50 per cent of respondents in the Labour category trust the union and that trust in the unions declines for clerical workers and Administration Officers and is lowest with the Middle Managers. Surprisingly, for the Senior Management the trust in the union (48 per cent) is almost as high as for the labourers. This indicates that Middle Management can often be overruled by their Senior Managers. They find themselves in the middle of a political alliance which cuts across the administrative procedures. The confusion of roles evident in the hierarchy of trust in the Limpopo Province Public Service explicates a parallel process to that of cultural identity and solidarity.

The further from the centres or nodes of modernity the greater the influence of tradition and custom, the more tribality dominates. However, the influence at the centre should not to be underestimated, as much of it is covert, and denied. But it is clearly a matter of degree.

Many of these influences are covert. Exacerbating the situation is the denial around such issues. This denial stems from the elites buying into the global paradigm as well as embarrassment and playing of roles to accommodate the demands of modernity. Sometimes the application of so-called African Management can collude with the disruption of organisational functioning rather than helping.

This is not going to change unless we recognise and acknowledge the competing value systems and do something to harmonise them. At present we are merely allowing them to find their own way, damaging organisational and institutional growth.

The central problem is the confrontation between merit and organisational politics that really arises from outside the organisation itself. Merit builds respect while a politically riddled organisation builds contempt. And this is something that all the spin doctors cannot gloss over. If these processes are left unchecked it eventually leads to situation of a war of all against all for position. The following caricature illuminates the situation that arises from the abuse of Affirmative Action: ‘If I have a job that I cannot do, and you have a better position, with better pay and perks, that you cannot do, then why can’t I not do your job?’

We desperately need to come to terms with the fact that as soon as we allow interests external to the goals of the organisation to influence decisions within the organisation we encourage the fudging of roles and interests. External interests can influence all levels of functioning, from CEOs to streetsweepers. All decisions at all these levels can be influenced allowing policies to be hijacked for interests other than those of the organisation as a whole. The organisation can be hijacked by any of a multiplicity of interests whether they be political (i.e., camaraderie), tribal, ethnic, clan, family, broerskap or whatever kind of favouritism. It merely depends on who the home boys or girls are. Favouritism opens the possibility for self-interested motives to corrupt processes, masked in the rhetoric of the ruling policy environment. For example:

– Appointment of unqualified homey is sometimes masked as affirmative action;

– Taking kickbacks or giving oneself contracts is even rationalized as empowerment;

– Hard decisions are not taken and incompetence is excused for a myriad of reasons.

In rural areas, especially, we have to find a way to work with the traditional structures, if we are to make organisations work. It is necessary to deal with the social and psychological impacts of rapid urbanisation on people. If we do not talk about the conflicts in people’s minds, caught between the demands of custom and tradition and the demands of modern enterprise conflict may be exacerbated. Denial fosters the conflict between tradition and modernity undermining morality and subverting all enterprise. There is a dire need to assist people to change in a way that is consistent with their values and more importantly allow and encourage so-called tradition to develop the wealth it contains for the benefit of society. As Mafeje (1996: 20) comments, noting the growing number of voices raising the issue of ‘… the relationship between culture and development in Africa’:

The underlying presupposition is that Africans have not fared well so far precisely because they have abandoned their own cultures and languages in favour of alien culture and language. While the correlation might not be as simple as such presuppositions imply, there is an obvious need for re-evaluating African experience so as to discover what went wrong, and how best it could be corrected, relying on homegrown remedies.

While the assimilation of alien culture and language has been led by the elites, its absorption further down has been far weaker. It is urgent that African intellectuals incubate a dialogue between tradition and modernity, as is happening in India and other third world countries that are successfully resolving this complex of difficult issues and find ways to come to terms with modernity. All particularities need to find a modernization that begins to harmonise with their indigenous knowledge and value systems.

These notes talk at the micro level to the need for an African management that can synergise management principles with the demands of custom and tradition as well as for custom and tradition to harness the management of human capital towards African solutions to Africa’s problems.

Towards the future

There is a rising awareness of the need to deal with the cultural question. The frenzied attempt to deny cultural relativity is waning. A Brussels Seminar at the European Commission (1998) proposed a ‘double hypothesis’:

– ‘That we are in transition to a transmodern way of thinking that combines intuition and spirituality with rational brainwork;

– That 21st century conflicts will likely be not between religions or cultures but within them, between premodern, modern, and transmodern worldviews’.

Luyckx continues: ‘Non-Western thinkers find this framework useful: it opens a door to criticism of the worst aspects of modernity without being ‘anti-Western’ (1998:974).

Inayatullah (2000: 7) comments that ‘like death, the West has become ubiquitous. But will hegemony continue and are there any signals of possible transformation from within and without?’ Inayatullah proposed the following four alternatives for the West: A dramatic ageing population leading to a future where immigrants are required for survival, however, once in the holy land of Disney, multiculturalism may make porous the West itself;

– Genocide against the Other, resisting internal transformative processes;

– The Artificial Society, wherein diversity and the Other are pushed back since high productivity can be achieved through the new information and genetic technologies, that is, through reductionist science and linear economic progress; While the latter technocratic scenario is most likely, there are possibilities that a more multicultural, Gaian, communicative, globalist future may emerge.

While, perhaps, a little idealistic, Inayatullah captures the possible futures before us. Perhaps we will negotiate future hybrids. But socially engineered simulations will simply not wash. Perhaps, hybrids with integrity? But this will be a rocky path and the warning made by Jan Christian Smuts more than a century ago, during another outbreak of a particularity resisting colonialism, the Boer War, reflects this:

History will show convincingly that the pleas of humanity, civilization, and equal rights, upon which the British Government bases its actions, are nothing else but the recrudescence of that spirit of annexation and plunder which has at all times characterized its dealings with our people (Smuts 1900: 3).

Can the global heed the warnings, or will it arrogantly attempt to impose its will, annihilating all particularities? Baudrillard, echoing Inayatullah’s second alternative, warns somewhat prophetically:

Our wars thus have less to do with the confrontation of warriors than with the domestication of the refractory forces on the planet, those uncontrollable elements as the police would say, to which belong not only Islam in its entirety but wild ethnic groups, minority languages etc. All that is singular and irreducible must be reduced and absorbed. In this sense, the Iran-Iraq war was a successful first phase: Iraq served to liquidate the most radical form of the anti-Western challenge, even though it neverdefeated it (1995: 86).

Dialogue needs to escape the ‘good guy – bad guy’ level of political discussion so predominant in world affairs today. This is accurately reflected in the exposition of the goings on at Abu Graib Prison in Iraq as well as other interviews with US troops in Iraq. The American troops vilify and hate the people they are fighting. Also, the congressman who, after viewing pictures from the prison showing Iraqi women having to display their breasts, noted that he had not seen any violence. That is violence to the Iraqi women.

Politics is not about good guys and bad guys, or ‘good and evil’ as President Bush would have us believe. Politics is about conflicts of interests, whether they be spiritual, cultural, social, political and/or economic. Unless particularities are taken seriously, acknowledging conflicts of interest for what they are and respecting their histories and aspirations, little progress can be made in management or in world affairs. More problematically, if we are to stop the terrible talk of good and evil as unleashed by the dangerous dialogue world leaders are flirting with in their ‘War on Terrorism’ from spiralling out of control, the world will have to act swiftly or the chance for dialoguewill dissolve in mistrust, loathing and the maligning of the ‘other’. As Wole Akande (2002) has noted: