De mysterieuze dood van een priestervorst

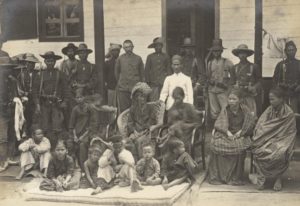

De 2e man van rechts is Adranoes Lohij, de oppasser ofwel dardanel van overste Veltman, staand tussen een aantal Atjehse teukoe’s. Op zijn borst de Militaire Willems-Orde en de bronzen medaille voor Menslievend Hulpbetoon.

De tentoonstelling ‘De Laatste Batakkoning’ in 2008 in Museum Bronbeek en het daaraan gekoppelde boek gaven een helder beeld wat er voorafging aan de dood van Si Singamangaraja. Het boek, grotendeels samengesteld uit onderzoek van Harm Stevens, is voorzien van vele originele documenten die de lezer meeneemt naar een roerige tijd. Een periode waarin de laatste verzetshaarden worden uitgeschakeld en grote delen van het archipel worden onderworpen aan het koloniaal gezag.

Over de momenten van het leven van de Batakkoning bestaan verschillende lezingen. Met het ontsluiten van een oude foto, met daarop een inheemse ex-militair met onderschrift ‘Oppasser van overste Veltman’ kwamen er nieuwe feiten aan het licht.

De twaalfde Si Singamangaraja

Ompoe Pulo Batu was de twaalfde Si Singamangaraja ofwel Leeuwenvorst in erfopvolging en gold voor zijn volk als heilige. Door een sluier van mystiek die om hem heen hing en zijn hiërarchische positie in de lijn van de offerpriesters, werd hij door de westerse wereld aangeduid als de priestervorst. De in 1849 geboren priestervorst had zich net als de twee voorgaande Si Singamangaraja’s gevestigd in Bakara, gelegen ten zuidwesten van het Tobameer op Noord-Sumatra. De Bataks, gevestigd rond het Tobameer, leefden veelal autonoom en vormden midden negentiende eeuw nog niet een volk. Maar door het opdringen van het Nederlands-gouvernement en de steeds groter wordende invloed van de zending, onder aanvoering van veelal Duitse zendelingen in de laatste kwart van de negentiende eeuw, kregen de Bataks een gemeenschappelijke vijand. Dit leidde in 1883 tot een opstand onder ruim 9000 Toba-Bataks gericht tegen de westerse indringers. Door het geweld ging alles wat westers was in rook op, maar ook de bekeerde Batak-kampongs moesten het ontgelden. De schrik zat er goed in bij de Europeanen en zij velen verlieten hals over kop het Batak-gebied. De priestervorst werd gezien als leider van deze opstand en het Nederlands-gouvernement gelastte in datzelfde jaar het Nederlands Indisch Leger met een strafexpeditie tegen de priestervorst. 4 maanden lang woedde er oorlog het Batak-gebied. Nadat het Nederlands Indisch Leger op 12 augustus zijn residentie in Bakara had bereikt, was de priestervorst al met zijn gevolg gevlucht naar Lintong in de hoger gelegen oerwouden ten zuiden van het Tobameer. Bakara werd door het Nederlands Indisch Leger ‘getuchtigd’ of beter gezegd, geheel verwoest. Het zou tot 1904 duren voor er een nieuwe serieuze poging werd ondernomen om het verzet te breken. De tocht van overste Van Daalen door de Gajo, Alas en Bataklanden, maakte aan vele illusies van het verzet in de binnenlanden van Noord-Sumatra snel een eind. Met een golf van geweld trokken tweehonderd marechaussees ruim vijf maanden lang door de oerwouden van Noord-Sumatra. De marechaussees kwamen ook in het gebied van priestervorst, echter was hij net als in 1883 niet vindbaar. Met de expeditie van Hendrikus Colijn, de latere minister-president van Nederland, werd eind 1904 een nieuwe poging ondernomen. Ook toen werd er geen contact gemaakt met de priestervorst.

Brief van Si Singa Mangaradja, die regeert over de Bataks, gericht aan de heer ‘overste generaal, leider van de oorlog van de kompenie’.

‘De brief is aan u gericht omdat u oorlog voert in het land van de Bataks en mijn onderdanen gevangen heeft genomen. Maar ik heb ook woorden ontvangen van de grote heer van Medan en de resident van Tampanoeli (Batak gebied) en van de controleur, zij zeggen geen oorlog te zullen voeren tegen mij en degene waar ik over regeer.

Heb alle betrokkenen een brief gegeven dat er vrede is en ik een oorlog zal voeren tegen de kompenie. Ik zeg nu tegen de ‘overste generaal’, keert gij terug, en ga niet met mij en degene waar ik over regeer in oorlog. Het is toch niet geoorloofd om mij en mijn onderdanen lastig te vallen. Keer terug, anders overtreed u de regeles van de woorden van vrede en afspraak, die gemaakt zijn met de resident van Medan.

En als er klachten zijn over mijn onderdanen, richt u tot mij. Mijn onderdanen willen geen moeilijkheden.

Keer terug, anders overtreed u de regeles van de woorden van vrede en afspraak, die gemaakt zijn met de resident van Medan.

Zo zij het.

3 november 1904′

In de daaropvolgende jaren werden diverse kleine expedities ondernomen om de priestervorst op te sporen, echter zonder resultaat. Op 1 maart 1907 deed assistent-resident der Bataklanden een oproep aan het gouvernement. De onrust, die de ongrijpbare priestervorst met zich mee bracht, moest snel ten einde worden gebracht. Zijn oproep luidde letterlijk: “De buitengewone toestand eischt daarom buitengewone maatregelen: tydelijke verwydering van alle ongewenste elementen en de beschikbaarstelling van eenige flinke marechaussee onder een beproefde aanvoerder b.v. de kapitein Christoffel, aan wien zooveel mogelyk de vrye hand moet worden gelaten…..”.

Anderhalve maand later was kapitein Christoffel, een doorgewinterde marechaussee officier die een deel van de Bataklanden al eens had bezocht tijdens de tocht van overste Van Daalen in 1904, met 4 brigades marechaussee op zoek naar de schuilplaats van Si Singamangaraja. De vier marechausseebrigades onder bevel van Christoffel waren ruim tweeëneenhalve maand op expeditie voordat zij hun doel, de schuilplaats van priestervorst, hadden bereikt.Het was een barre tocht over de ruige hooglanden en door oerwouden van Midden-Sumatra. Op 24 april 1907 maakte een van de brigades contact met de ‘bende’ in Lintong. Daarbij vertoonde de Ambonese marechaussee Lohij volgens koninklijk besluit van 7 maart 1908, No 55 “grooten moed, veel beleid, voortvarendheid en trouwe plichtbetrachting”. Door zijn optreden werd, Ompoe Radja Boli van Lintong, de vader van de belangrijkste verzetsleider Ompoe Babiat gearresteerd en de oudste zoon van de priestervorst, Soetan Nagari, ‘onschadelijk’ gemaakt. Daarbij werd zijn geweer M95 buitgemaakt.

Adranoes Lohij had zich in 1896 te Saparoea vrijwillig aangemeld bij het Nederlands Indisch Leger. Twaalf jaar later was deze marechaussee rijkelijk gedecoreerd met onder andere de bronzen medaille voor Menslievend Hulpbetoon en de Militaire Willem-Orde. De laatste en tevens hoogste onderscheiding kreeg hij voor zijn aandeel van het opsporen en onschadelijk maken van Si Singamangaraja op 24 april en 17 juni 1907. Zijn militair carrière verliep niet zonder kleerscheuren. Hij raakte diverse keren gewond door klewanghouwen en rentjong-steken aan hand, arm, borstholte, bovenbeen en knie. Lohij overleed in 1914 op 38 jarige leeftijd.

Johannes Rotikan meldde zich in Menado, hetzelfde jaar als Lohij, aan bij het Nederlands Indisch Leger. Ook hij maakte enkele jaren deel uit van het korps marechaussee en was net als Lohij door de Atjeh-oorlog inmiddels een geharde militair. Op 17 juni 1907, tijdens de overval op de schuilplaats van Si Singamangaraja nabij Pea Radja, zette Rotikan, Lohij en 2 andere marechaussees de achtervolging in op de vluchtende Si Singamangaraja. In het ravijn wordt de priestervorst ingehaald en omsingeld door de 4 marechaussees en doodgeschoten. Rotikan werd een klein jaar later benoemd tot ridder in de Militaire Willems-Orde 4e klasse bij koninklijk besluit van 7 maart 1908, No 55. “Zich onderscheiden bij de krijgsverrichtingen in de residentie Tapanoeli, hoofdzakelijk in het eerste halfjaar 1907. 17 juni 1907 overval van eene schuilplaats van Si Singamangaradja nabij Pea Radja. Blijken te geven van buitengewoon moed door den priestervorst Si Singamangaradja met behulp van 3 andere marechaussees te omsingelen, onversaagd stand te houden, toen de vorst hem met een rentjong onverwacht aanviel en dezen daarop kalm neer te schieten.”

Dit relaas komt grotendeels overeen met de citaten uit het dagboek van de eerste-luitenant J.H. Van Temmen, die de expeditie in 1907 meemaakte als ondercommandant. Hij beschrijft hoe de marechaussees de priestervorst inhalen en omsingelen. Daarbij roept de voorste marechaussee: tarok rentjong, tarok rentjong ofwel taroeh rentjong. Hij beveelt de rentjong neer te leggen. Maar de priestervorst legt deze niet neer, hij roept: djangan passang ofwel niet schieten. De priestervorst schijnt op dat moment ook zijn rentjong uit de schede te halen.

Feitelijk beschrijft Van Temmen bijna hetzelfde als de inschrijving in het register der Militaire Willems-Orde, handelend uit zelfverdediging. Echter bestaat er nog een tweede versie van het relaas die net als de citaten van Van Temmen zijn opgenomen in het Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlands Aardrijkskundig Genootschap van 1944. Deze tweede versie is van de oudste dochter van Si Singamangaraja, Rinsan. Zij was net als haar vader op de vlucht geslagen toen de overval begon. Zij liep een aantal meters voor haar vader, totdat zij het bevel hoorde om te blijven staan. Ze keek om en besefte dat dit commando niet voor haar was bedoeld, maar voor haar vader. Zij hoorde haar vader zeggen “Ahoe Si Singa Mangaraja” ofwel ik ben het SiSingamangaraja.Een marechaussee riep “tarik rentjong, tarik rentjong” ofwel trek je wapen uit, trek je wapen uit. Haar vader herhaalde nog “Ahoe Si Singa Mangaraja”. Daarna hoorde zij slechts geknal en geschreeuw. Toen ze zich terug haastte, zag ze een militair met een lange snor die haar levenloze vader fouilleerde. Zij begreep niet dat haar vader, die zich wilde overgeven, toch werd neergeschoten. De lichamen van Si Singamangaraja en zijn twee jonge zonen werden naar de markt van Balige gebracht en tentoongesteld, zodat de bevolking kon zien dat hun vorst gesneuveld was en het verzet zinloos was.

De twee versies staan haaks tegenover elkaar; was het zelfverdediging of werd de priestervorst ‘neergelegd’. Een term die veelal werd gebruikt bij het uitschakelen van verzetsleiders tijdens de Atjeh-oorlog. Het inzetten van kapitein Christoffel voor deze ‘klus’ doet het laatste vermoeden. Echter heeft deze rijk gedecoreerde militair al zijn persoonlijke aantekeningen verbrand en rest er slechts nog een officieel relaas.

Een aantal zaken kan men op zijn minst als opmerkelijk beschouwen

De benoeming van 2 marechaussees tot Ridder in de Militaire Willems Orde, die feitelijk waren gekoppeld aan het sneuvelen van de oudste zoon van Si Singamangaraja, de omsingeling en het sneuvelen van Si Singamangaraja, was tot aan de dag van vandaag onbekend. Daarnaast werd de priestervorst volgens de inschrijving van het register door totaal 4 marechaussees ingesloten, wat niet in de publicaties is terug te vinden.

In het artikel “Het sneuvelen van de Si Singamangaraja”, in het Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlands Aardrijkskundig Genootschap van 1944 is een foto gepubliceerd. Deze was beschikbaar gesteld uit de collectie van W.K.H. Ypes, met de aanduiding foto 6. De foto is gemaakt na het sneuvelen van de priestervorst. De oude vrouw in de rotanstoel is de moeder van de priestervorst, rechts en links naast haar zijn voornaamste vrouwen en de rest van zijn naaste familieleden. Op de achtergrond militairen van het korps marechaussee.

Een bijna identieke foto uit de collectie W.K.H. Ypes, die niet gepubliceerd is het Koninklijk Nederlands Aardrijkskundig Genootschap van 1944, vertoont een interessant detail. Er staat een militair op die op de beschikbaar gestelde en gepubliceerde foto niet staat. De militair is Adranoes Lohij, een van de 2 benoemde ridders. Opmerkelijk is ook dat er geen (bekende) officieren op de foto staan, ‘slechts’ een Europese onderluitenant, staand in de achterste rij zonder hoed.

Er zijn vele hypotheses te bedenken over de ware toedracht van de dood van de priestervorst. De enige echte getuigen hebben hun verhaal nooit in het openbaar kunnen vertellen of misschien beter gezegd hebben het nooit mogen vertellen. Zelfs in de bekende Atjeh- en marechaussee boeken wordt de dood van de mystieke priestervorst niet meer genoemd. Het doet vermoeden dat de gehele affaire snel vergeten moest worden. Het gouvernement was zeer niet ontevreden met het behaalde resultaat van kapitein Christoffel. Zoals het Nieuwsblad van het Noorden op 22 juni 1907 schreef: “Nu Singa Mangaradja gesneuveld is, behoeft men zich niet het hoofd te breken met de rol, die hem verder zou worden toegedeeld.”

Si Singamangaraja kreeg per presidentieel discreet de titel Pahlawan Nasional Indonesia ofwel held van Indonesië.

Eerder gepubliceerd op: https://kleinnagelvoort.wordpress.com/de-mysterieuze-dood-van-een-priestervorst/

Het blog van John Klein Nagelvoort – Een verzameling verhalen uit ons koloniaal verleden: : https://kleinnagelvoort.wordpress.com/