Trump’s America And The New World Order: A Conversation With Noam Chomsky

For the prelude to this interview, read yesterday’s conversation with Noam Chomsky on “Trump and the Flawed Nature of US Democracy“, which exposes the pitfalls of the political system that made Trump’s rise to power a reality.

Are Donald Trump’s selections for his cabinet and other top administration positions indicative of a man who is ready to “drain the swamp?” Is the president-elect bent on putting China on the defensive? What does he have in mind for the Middle East? And why did Barack Obama choose at this juncture — that is, toward the end of his presidency — to have the US abstain from a UN resolution condemning Israeli settlements? Are new trends and tendencies in the world order emerging? In this exclusive Truthout interview, Noam Chomsky addresses these critical questions just two weeks before the White House receives its new occupant.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, the president-elect’s cabinet is being filled by financial and corporate bigwigs and military leaders. Such selections hardly reconcile with Trump’s pre-election promises to “drain the swamp,” so what should we expect from this megalomaniac and phony populist insofar as the future of the Washington establishment is concerned?

Noam Chomsky: In this respect — note the qualification — Time magazine put it fairly well (in a Dec. 26 column by Joe Klein): “While some supporters may balk, Trump’s decision to embrace those who have wallowed in the Washington muck has spread a sense of relief among the capital’s political class. ‘It shows,’ says one GOP consultant close to the President-elect’s transition, ‘that he’s going to govern like a normal Republican’.”

There surely is some truth to this. Business and investors plainly think so. The stock market boomed right after the election, led by the financial companies that Trump denounced during his campaign, particularly the leading demon of his rhetoric, Goldman Sachs. According to Bloomberg News, “The firm’s surging stock price,” up 30 percent in the month after the election, “has been the largest driver behind the Dow Jones Industrial Average’s climb toward 20,000.” The stellar market performance of Goldman Sachs is based largely on Trump’s reliance on the demon to run the economy, buttressed by the promised roll-back in regulations, setting the stage for the next financial crisis (and taxpayer bailout). Other big gainers are energy corporations, health insurers and construction firms, all expecting huge profits from the administration’s announced plans. These include a Paul Ryan-style fiscal program of tax cuts for the rich and corporations, increased military spending, turning the health system over even more to insurance companies with predictable consequences, taxpayer largesse for a privatized form of credit-based infrastructure development, and other “normal Republican” gifts to wealth and privilege at taxpayer expense. Rather plausibly, economist Larry Summers describes the fiscal program as “the most misguided set of tax changes in US history [which] will massively favor the top 1 per cent of income earners, threaten an explosive rise in federal debt, complicate the tax code and do little if anything to spur growth.”

But, great news for those who matter.

There are, however, some losers in the corporate system. Since November 8, gun sales, which more than doubled under Obama, have been dropping sharply, perhaps because of lessened fears that the government will take away the assault rifles and other armaments we need to protect ourselves from the Feds. Sales rose through the year as polls showed Clinton in the lead, but after the election, the Financial Times reported, “shares in gun makers such as Smith & Wesson and Sturm Ruger plunged.” By mid-December, “the two companies had fallen 24 per cent and 17 per cent since the election, respectively.” But all is not lost for the industry. As a spokesman explains, “To put it in perspective, US consumer sales of firearms are greater than the rest of the world combined. It’s a pretty big market.”

Normal Republicans cheer Trump’s choice for Office of Management and Budget, Mick Mulvaney, one of the most extreme fiscal hawks, though a problem does arise. How will a fiscal hawk manage a budget designed to massively escalate the deficit? In a post-fact world, maybe that doesn’t matter.

Also cheering to “normal Republicans” is the choice of the radically anti-labor Andy Puzder for secretary of labor, though here too a contradiction may lurk in the background. As the ultrarich CEO of restaurant chains, he relies on the most easily exploited non-union labor for the dirty work, typically immigrants, which doesn’t comport well with the plans to deport them en masse. The same problem arises for the infrastructure programs; the private firms that are set to profit from these initiatives rely heavily on the same labor source, though perhaps that problem can be finessed by redesigning the “beautiful wall” so that it will only keep out Muslims.

Is this to say then that Trump will be a “normal” Republican as America’s 45th President?

In such respects as the ones mentioned above, Trump proved himself very quickly to be a normal Republican, if to the extremist side. But in other respects he may not be a normal Republican, if that means something like a mainstream establishment Republican — people like Mitt Romney, whom Trump went out of his way to humiliate in his familiar style, just as he did to McCain and others of this category. But it’s not only his style that causes offense and concern. His actions do as well.

Take just the two most significant issues that we face, the most significant that humans have ever faced in their brief history on earth; issues that bear on species survival: nuclear war and global warming. Shivers went up the spine of many “normal Republicans,” as of others who care about the fate of the species, when Trump tweeted that “The United States must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability until such time as the world comes to its senses regarding nukes.” Expanding nuclear capability means casting to the winds the treaties that have sharply reduced nuclear arsenals and that sane analysts hope may reduce them much further, in fact, to zero, as advocated by such normal Republicans as Henry Kissinger and Reagan Secretary of State George Shultz, and by Reagan, in some of his moments. Concerns did not abate when Trump went on to tell the cohost of TV show Morning Joe “Let it be an arms race. We will outmatch them at every pass.” And it wasn’t too comforting even when his White House team tried to explain that “The Donald” didn’t say what he said.

Nor do concerns abate because Trump was presumably reacting to Putin’s statement: “We need to strengthen the military potential of strategic nuclear forces, especially with missile complexes that can reliably penetrate any existing and prospective missile defense systems. We must carefully monitor any changes in the balance of power and in the political-military situation in the world, especially along Russian borders, and quickly adapt plans for neutralizing threats to our country.”

Whatever one thinks of these words, they have a defensive cast and as Putin has stressed, they are in large part a reaction to the highly provocative installation of a missile defense system on Russia’s border on the pretext of defense against nonexistent Iranian weapons. Trump’s tweet intensifies fears about how he might react when crossed, for example, by unwillingness of some adversary to bow to his vaunted negotiating skills. If the past is any guide he might, after all, find himself in a situation where he must decide within a few minutes whether to blow up the world.

The other crucial issue is environmental catastrophe. It cannot be stressed too strongly that Trump won two victories on November 8: the lesser one in the Electoral College and the greater one in Marrakech, where some 200 countries were seeking to put teeth in the promises of the Paris negotiations on climate change. On Election Day, the conference heard a dire report on the state of the Anthropocene from the World Meteorological Organization. As the results of the election came in, the stunned participants virtually abandoned the proceedings, wondering if anything could survive the withdrawal of the most powerful state in world history. Nor can one stress too often the astonishing spectacle of the world placing its hopes for salvation in China, while the leader of the free world stands alone as a wrecking machine.

Although — amazingly — most ignored these astounding events, establishment circles did have some response. In Foreign Affairs, Varun Sivaram and Sagatom Saha warned of the costs to the US of “ceding climate leadership to China,” and the dangers to the world because China “would lead on climate-change issues only insofar as doing so would advance its national interests” —

unlike the altruistic United States, which supposedly labors selflessly only for the benefit of mankind.

How intent Trump is on driving the world to the precipice was revealed by his appointments, including his choice of two militant climate change deniers, Myron Ebell and Scott Pruit, to take charge of dismantling the Environmental Protection Agency that was established under Richard Nixon, with another denier slated to head the Department of Interior.

But that’s only the beginning. The cabinet appointments would be comical if the implications were not so serious. For Department of Energy, a man who said it should be eliminated (when he could remember its name) and is perhaps unaware that its main concern is nuclear weapons. For Department of Education, another billionaire, Betsy DeVos, who is dedicated to undermining and perhaps eliminating the public school system and who, as Lawrence Krause reminds us in the New Yorker, is a fundamentalist Christian member of a Protestant denomination holding that “all scientific theories be subject to Scripture” and that “Humanity is created in the image of God; all theorizing that minimizes this fact and all theories of evolution that deny the creative activity of God are rejected.” Perhaps the Department should request funding from Saudi sponsors of Wahhabi madrassas to help the process along.

DeVos’s appointment is no doubt attractive to the evangelicals who flocked to Trump’s standard and constitute a large part of the base of today’s Republican Party. She should also be able to work amicably with Vice-President-elect Mike Pence, one of the “prized warriors [of] a cabal of vicious zealots who have long craved an extremist Christian theocracy,” as Jeremy Scahill details in The Intercept, reviewing his shocking record on other matters as well.

And so it continues, case by case. But not to worry. As James Madison assured his colleagues as they were framing the Constitution, a national republic would “extract from the mass of the Society the purest and noblest characters which it contains.”

What about the choice of Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State?

One partial exception to the above is choice of ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson for Secretary of State, which has aroused some hope among those across the spectrum who are rightly concerned with the rising and extremely hazardous tensions with Russia. Tillerson, like Trump in some of his pronouncements, has called for diplomacy rather than confrontation, which is all to the good — until we remember the sable lining of the beam of sunshine. The motive is to allow ExxonMobil to exploit vast Siberian oil fields and so to accelerate the race to disaster to which Trump and associates, and the Republican Party rather generally, are committed.

And how about Trump’s national security staff — do they fit the mold of “normal” Republicans, or are they also part of the extreme Right?

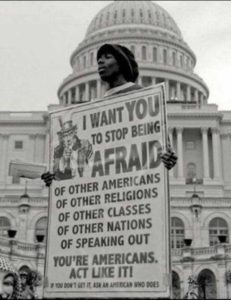

Normal Republicans might be somewhat ambivalent about Trump’s national security staff. It is led by National Security Advisor Gen. Michael Flynn, a radical Islamophobe who declares that Islam is not a religion but rather, a political ideology, like fascism, which is at war with us, so we must defend ourselves, presumably against the whole Muslim world — a fine recipe for generating terrorists, not to speak of far worse consequences. Like the Red Menace of earlier years, this Islamic ideology is penetrating deep into American society, Flynn declaims. They are, he says, being helped by Democrats, who have voted to impose Sharia law in Florida, much as their predecessors served the Commies, as Joe McCarthy famously demonstrated. Indeed, there are “over 100 cases around the country,” including Texas, Flynn warned in a speech in San Antonio. To ward off the imminent threat, Flynn is a board member of ACT!, which pushes state laws banning Sharia law, plainly an imminent threat in states like Oklahoma, where 70 percent of voters approved legislation to prevent the courts from applying this grim menace to the judicial system.

Second to Flynn in the national security apparatus is Secretary of Defense Gen. James “Mad Dog” Mattis, considered a relative moderate. Mad Dog has explained that “It’s fun to shoot some people.” He achieved his fame by leading the assault on Fallujah in November 2004, one of the most vicious crimes of the Iraq invasion. A man who is “just great,” according to the president-elect: “the closest thing we have to Gen. George Patton.”

In your view, is Trump bent on a collision course with China?

It’s hard to say. Concerns were voiced about Trump’s attitudes toward China, again full of contradictions, particularly his pronouncements on trade, which are almost meaningless in the current system of corporate globalization and complex international supply chains. Eyebrows were raised over his sharp departure from long-standing policy in his phone call with Taiwan’s president, but even more by his implying that the US might reject China’s concerns over Taiwan unless China accepts his trade proposals, thus linking trade policy “to an issue of great-power politics over which China may be willing to go to war,” the business press warned.

What of Trump’s views and stance on the Middle East? They seem to be in line with those of “normal” Republicans, right?

Unlike with China, normal Republicans did not seem dismayed by Trump’s tweet foray into Middle East diplomacy, again breaking with standard protocol, demanding that Obama veto UN Security Council resolution 2334, which reaffirmed “that the policy and practices of Israel in establishing settlements in the Palestinian and other Arab territories occupied since 1967 have no legal validity and constitute a serious obstruction to achieving a comprehensive, just and lasting peace in the Middle East [and] Calls once more upon Israel, as the occupying Power, to abide scrupulously by the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention, to rescind its previous measures and to desist from taking any action which would result in changing the legal status and geographical nature and materially affecting the demographic composition of the Arab territories occupied since 1967, including Jerusalem, and, in particular, not to transfer parts of its own civilian population into the occupied Arab territories.”

Nor did they object when he informed Israel that it can ignore the lame duck administration and just wait until January 20, when all will be in order. What kind of order? That remains to be seen. Trump’s unpredictability serves as a word of caution.

What we know so far is Trump’s enthusiasm for the religious ultraright in Israel and the settler movement generally. Among his largest charitable contributions are gifts to the West Bank settlement of Beth El in honor of David Friedman, his choice as Ambassador to Israel. Friedman is president of American Friends of Beth El Institutions. The settlement, which is at the religious ultranationalist extreme of the settler movement, is also a favorite of the family of Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, reported to be one of Trump’s closest advisers. A lead beneficiary of the Kushner family’s contributions, the Israeli press reports, “is a yeshiva headed by a militant rabbi who has urged Israeli soldiers to disobey orders to evacuate settlements and who has argued that homosexual tendencies arise from eating certain foods.”Other beneficiaries include “a radical yeshiva in Yitzhar that has served as a base for violent attacks against Palestinian’s villages and Israeli security forces.”

In isolation from the world, Friedman does not regard Israeli settlement activity as illegal and opposes a ban on construction for Jewish settlers in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. In fact, he appears to favor Israel’s annexation of the West Bank. That would not pose a problem for the Jewish state, Friedman explains, since the number of Palestinians living in the West Bank is exaggerated and therefore a large Jewish majority would remain after annexation. In a post-fact world, such pronouncements are legitimate, though they might become accurate in the boring world of fact after another mass expulsion. Jews who support the international consensus on a two-state settlement are not just wrong, Friedman says, they are “worse than kapos,” the Jews who were controlling other inmates in service to their Nazi masters in the concentration camps — the ultimate insult.

On receiving the report of his nomination, Friedman said he looked forward to moving the US embassy to “Israel’s eternal capital, Jerusalem,” in accord with Trump’s announced plans. In the past, such proposals were withdrawn, but today they might actually be fulfilled, perhaps advancing the prospects of a war with the Muslim world, as Trump’s National Security Adviser appears to recommend.

Returning to UNSC 2334 and its interesting aftermath, it is important to recognize that the resolution is nothing new. The quote given above was not from UNSC 2334 but from UNSC Resolution 446, passed on March 12, 1979, reiterated in essence in UNSC 2334.

UNSC 446 passed 12-0 with the US abstaining, joined by the UK and Norway. Several resolutions followed, reaffirming 446. One resolution of particular interest was even stronger than 446-2334, calling on Israel “to dismantle the existing settlements” (UNSC Resolution 465, passed in March 1980). This resolution passed unanimously, no abstentions.

The Government of Israel did not have to wait for the UN Security Council (and more recently, the World Court) to learn that its settlements are in gross violation of international law. In September 1967, only weeks after Israel’s conquest of the occupied territories, in a Top Secret document, the government was informed by the legal adviser to [Israel’s] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the distinguished international lawyer Theodor Meron, that “civilian settlement in the administered territories [Israel’s term for the occupied territories] contravenes explicit provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention.” Meron explained further that the prohibition against transfer of settlers to the occupied territories “is categorical and not conditional upon the motives for the transfer or its objectives. Its purpose is to prevent settlement in occupied territory of citizens of the occupying state.” Meron therefore advised that “If it is decided to go ahead with Jewish settlement in the administered territories, it seems to me vital, therefore, that settlement is carried out by military and not civilian entities. It is also important, in my view, that such settlement is in the framework of camps and is, on the face of it, of a temporary rather than permanent nature.”

Meron’s advice was followed. Settlement has often been disguised by the subterfuge suggested, the “temporary military entities” turning out later to be civilian settlements. The device of military settlement also has the advantage of providing a means to expel Palestinians from their lands on the pretext that a military zone is being established. Deceit was scrupulously planned, beginning as soon as Meron’s authoritative report was delivered to the government. As documented by Israeli scholar Avi Raz, in September 1967, on the day a second civilian settlement came into being in the West Bank, the government decided that “as a ‘cover’ for the purpose of [Israel’s] diplomatic campaign,” the new settlements should be presented as army settlements and the settlers should be given the necessary instructions in case they were asked about the nature of their settlement. The Foreign Ministry directed Israel’s diplomatic missions to present the settlements in the occupied territories as military “strongpoints” and to emphasize their alleged security importance.’

Similar practices continue to the present.

In response to the Security Council orders of 1979-80 to dismantle existing settlements and to establish no new ones, Israel undertook a rapid expansion of settlements with the cooperation of both of the major Israeli political blocs, Labor and Likud, always with lavish US material support.

The primary differences today are that the US is now alone against the whole world, and that it is a different world. Israel’s flagrant violations of Security Council orders, and of international law, are by now far more extreme than they were 35 years ago, and are arousing far greater condemnation in much of the world. The contents of Resolutions 446-2334 are therefore taken more seriously. Hence, the revealing reactions to 2334 and to Secretary of State John Kerry’s explanation of the US vote.

In the Arab world, the reactions seem to have been muted: We’ve been here before. In Europe they were generally supportive. In the US and Israel, in contrast, coverage and commentary were extensive, and there was considerable hysteria. These are further indications of the increasing isolation of the US on the world stage. Under Obama, that is. Under Trump US isolation will likely increase further and indeed, already did, even before he took office, as we have seen.

Why did Obama choose abstention from the UN vote on Israeli settlements at this juncture, i.e., only a month or so before the end of his presidency?

Just why Obama chose abstention rather than veto is an open question; we do not have direct evidence. But there are some plausible guesses. There had been some ripples of surprise (and ridicule) after Obama’s February 2011 veto of a UNSC Resolution calling for implementation of official US policy, and he may have felt that it would be too much to repeat it if he is to salvage anything of his tattered legacy among sectors of the population that have some concern for international law and human rights. It is also worth remembering that among liberal Democrats, if not Congress, and particularly among the young, opinion about Israel-Palestine has been moving toward criticism of Israeli policies in recent years, so much so that 60 percent of Democrats “support imposing sanctions or more serious action” in reaction to Israeli settlements, according to a December 2016 Brookings Institute poll. By now the core of support for Israeli policies in the US has shifted to the far right, including the evangelical base of the Republican Party. Perhaps these were factors in Obama’s decision, with his legacy in mind.

The 2016 abstention aroused furor in Israel and in the US Congress as well, among both Republicans and leading Democrats, including proposals to defund the UN in retaliation for the world’s crime. Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu denounced Obama for his “underhanded, anti-Israel” actions. His office accused Obama of “colluding” behind the scenes with this “gang-up” by the Security Council, producing particles of “evidence” that hardly rise to the level of sick humor. A senior Israeli official added that the abstention “revealed the true face of the Obama administration,” adding that “now we can understand what we have been dealing with for the past eight years.”

Reality is rather different. Obama has, in fact, broken all records in support for Israel, both diplomatic and financial. The reality is described accurately by Financial Times Middle East specialist David Gardner: “Mr. Obama’s personal dealings with Mr. Netanyahu may often have been poisonous, but he has been the most pro-Israel of presidents: the most prodigal with military aid and reliable in wielding the US veto at the Security Council…. The election of Donald Trump has so far brought little more than turbo-frothed tweets to bear on this and other geopolitical knots. But the auguries are ominous. An irredentist government in Israel tilted towards the ultraright is now joined by a national populist administration in Washington fire-breathing Islamophobia.”

Public commentary on Obama’s decision and Kerry’s justification was split. Supporters generally agreed with Thomas Friedman that “Israel is clearly now on a path toward absorbing the West Bank’s 2.8 million Palestinians … posing a demographic and democratic challenge.”In a New York Times review of the state of the two-state solution defended by Obama-Kerry and threatened with extinction by Israeli policies, Max Fisher asks, “Are there other solutions?” He then turns to the possible alternatives, all of them “multiple versions of the so-called one-state solution” that poses a “demographic and democratic challenge”: too many Arabs — perhaps soon a majority — in a “Jewish and democratic state.”

In the conventional fashion, commentators assume that there are two alternatives: the two-state solution advocated by the world, or some version of the “one-state solution.” Ignored consistently is a third alternative, the one that Israel has been implementing quite systematically since shortly after the 1967 war and that is now very clearly taking shape before our eyes: a Greater Israel, sooner or later incorporated into Israel proper, including a vastly expanded Jerusalem (already annexed in violation of Security Council orders) and any other territories that Israel finds valuable, while excluding areas of heavy Palestinian population concentration and slowly removing Palestinians within the areas scheduled for incorporation within Greater Israel. As in neo-colonies generally, Palestinian elites will be able to enjoy western standards in Ramallah, with “90 per cent of the population of the West Bank living in 165 separate ‘islands,’ ostensibly under the control of the [Palestinian Authority]” but actual Israeli control, as reported by Nathan Thrall, senior analyst with the International Crisis Group.Gaza will remain under crushing siege, separated from the West Bank in violation of the Oslo Accords.

The third alternative is another piece of the “reality” described by David Gardner.

In an interesting and revealing comment, Netanyahu denounced the “gang-up” of the world as proof of “old-world bias against Israel,” a phrase reminiscent of Donald Rumsfeld’s Old Europe-New Europe distinction in 2003.

It will be recalled that the states of Old Europe were the bad guys, the major states of Europe, which dared to respect the opinions of the overwhelming majority of their populations and thus refused to join the US in the crime of the century, the invasion of Iraq. The states of New Europe were the good guys, which overruled an even larger majority and obeyed the master. The most honorable of the good guys was Spain’s Jose Maria Aznar, who rejected virtually unanimous opposition to the war in Spain and was rewarded by being invited to join Bush and Blair in announcing the invasion.

This quite illuminating display of utter contempt for democracy, along with others like it at the same time, passed virtually unnoticed, understandably. The task at the time was to praise Washington for its passionate dedication to democracy, as illustrated by “democracy promotion” in Iraq, which suddenly became the party line after the “single question” (will Saddam give up his WMD?) was answered the wrong way.

Netanyahu is adopting much the same stance. The old world that is biased against Israel is the entire UN Security Council; more specifically, anyone in the world who has some lingering commitment to international law and human rights. Luckily for the Israeli far right, that excludes the US Congress and — very forcefully — the president-elect and his associates.

The Israeli government is, of course, cognizant of these developments. It is therefore seeking to shift its base of support to authoritarian states, such as Singapore, China and Modi’s right-wing Hindu nationalist India, now becoming a very natural ally with its drift toward ultranationalism, reactionary internal policies and hatred of Islam. The reasons for Israel’s looking in this direction for support are outlined by Mark Heller, principal research associate at Tel Aviv’s Institution for National Security Studies. “Over the long term,” he explains, “there are problems for Israel in its relations with Western Europe and with the U.S.,” while in contrast, the important Asian countries “don’t seem to indicate much interest about how Israel gets along with the Palestinians, Arabs, or anyone else.” In short, China, India, Singapore and other favored allies are less influenced by the kinds of liberal and humane concerns that pose increasing threats to Israel.

Are we then in the midst of new trends and tendencies in world order?

I believe so, and the tendencies developing in world order merit some attention. As noted, the US is becoming even more isolated than it has been in recent years, when US-run polls — unreported in the US but surely known in Washington — revealed that world opinion regarded the US as by far the leading threat to world peace, no one else even close. Under Obama, the US is now alone in abstention on the illegal Israel settlements, against an otherwise unanimous Security Council. With President Trump joining his bipartisan congressional supporters on this issue, the US will be even more isolated in the world in support of Israeli crimes.

Since November 8, the US is isolated on the crucial matter of global warming, a threat to the survival of organized human life in anything like its present form. If Trump makes good on his promise to exit from the Iran deal, it is likely that the other participants will persist, leaving the US still more isolated from Europe.

The US is also much more isolated from its Latin American “backyard” than in the past, and will be even more isolated if Trump backs off from Obama’s halting steps to normalize relations with Cuba, undertaken to ward off the likelihood that the US would be pretty much excluded from hemispheric organizations because of its continuing assault on Cuba, in international isolation.

Much the same is happening in Asia, as even close US allies (apart from Japan) — and even the UK — flock to the China-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the China-based Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, in this case including Japan. The China-based Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) incorporates the Central Asian states, Siberia with its rich resources, India, Pakistan and soon, probably Iran, and perhaps Turkey. The SCO has rejected the US request for observer status and demanded that the US remove all military bases from the region.

Immediately after the Trump election, we witnessed the intriguing spectacle of German chancellor Angela Merkel taking the lead in lecturing Washington on liberal values and human rights. Meanwhile, since November 8, the world looks to China for leadership in saving the world from environmental catastrophe, while the US, in splendid isolation once again, devotes itself to undermining these efforts.

US isolation is not complete, of course. As was made very clear in the reaction to Trump’s electoral victory, the US has the enthusiastic support of the xenophobic ultraright in Europe, including its neofascist elements. The return of the right in parts of Latin America offers the US opportunities for alliances there as well. And the US retains its close alliance with the dictatorships of the Gulf and Egypt, and with Israel, which is also separating itself from more liberal and democratic sectors in Europe and linking with authoritarian regimes that are not concerned with Israel’s violations of international law and harsh attacks on elementary human rights.

The developing picture suggests the emergence of a New World Order, one that is rather different from the usual portrayals within the doctrinal system.