Punishment And Purpose ~ Penal Attitudes

3.1 Introduction

3.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter it has been argued that the practice of legal punishment in itself is morally problematic because it involves actions that would be considered wrong or evil in other contexts. The practice of legal punishment therefore demands a sound (moral) justification. Questions relating to the justification and subsequent goals of punishment have been considered in depth in a number of theoretical and philosophical approaches.

The gamut of theoretical perspectives concerning the justification and goals of punishment has been narrowed down to the general categories of Retributivism, Utilitarianism, Restorative Justice and mixed or hybrid theories. Paying due attention to the main controversies that (still) shape theoretical debate, Chapter 2 elaborated in some detail on the core arguments of these accounts of legal punishment. Radical theories were introduced, but not elaborated, since it was argued that they are of little relevance to the focus of this book, namely the study of attitudes of magistrates within the criminal justice system.

This chapter takes a more detailed look at the concept of penal attitude and its measurement. Penal attitudes are defined as attitudes towards the various purposes and functions of punishment. In turn, these purposes and functions of punishment are deduced from the philosophical theories discussed in the previous chapter. Section 3.2 elaborates in some more detail on the ‘attitude’ concept in general, and ‘penal attitudes’ in particular. A number of different approaches to the definition and use of the concept of penal attitudes is briefly presented. Section 3.3 explores and justifies the arguments of why it is important to try to measure such attitudes. It is argued that the measurement of penal attitudes is essential for any study that is directly or indirectly concerned with the link between moral theory and practice. Section 3.4 discusses various strategies that can be used for measuring penal attitudes including some of the practical and methodological issues. Research experiences in the Netherlands and abroad are introduced both for illustrative purposes and to highlight the pros and cons of the different approaches (and should not be viewed as an exhaustive review of such research).

3.2 What is a penal attitude?

In the previous section penal attitudes have been broadly defined as attitudes towards the various goals and functions of punishment. Although such a definition introduces the object of the attitudes, the actual meaning of the concept attitude remains unexplained. Before elaborating further on penal attitudes and their measurement, a somewhat more detailed discussion of the attitude concept is therefore merited.

Many texts concerning the study and measurement of attitudes mention Gordon Allport’s influential work (1935) as the historical bench mark for the application of the attitude concept in social-psychology. Indeed, Allport was among the first to systematically analyse and define the term attitude. However, as his own ‘History of the concept of attitude’ shows, many scholars before him had attempted to define and use it for scientific purposes (Allport, 1935, pp. 798–810). Allport traces the first use of the attitude concept in psychology back as far as 1862. After reviewing sixteen definitions of ‘attitude’ and identifying some common and useful elements, he presents his own definition of attitudes:

An attitude is a mental and neural state of readiness, organized through experience, exerting a directive or dynamic influence upon the individual’s response to all objects and situations with which it is related (Allport, 1935, p. 810).

Allport’s definition contains elements of the concept of attitude that are still generally accepted today.[i] However, to some this definition might seem unduly complex (Oskamp, 1977). Moreover, as Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) pointed out, “conceptual definitions will be most useful when they provide an adequate basis for the development of measurement procedures without trying to elaborate on the theoretical meaning of the concept” (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975, p. 6).

Traditionally, attitudes were said to be partitioned into three components: cognitive, affective, and conative (action tendency). There are, however, questions about the empirical validity of this partitioning because in practice the individual components may prove to be indistinguishable (McGuire, 1969; Oskamp, 1977). Furthermore, this partitioning has led to much confusion about the true meaning of the concept. It is therefore not surprising that in an extensive literature review, Fishbein and Ajzen (1972) found almost 500 different ways that were designed with the aim of measuring the concept attitude. However, they argue, many of these attempted to place a subject on a bipolar dimension indicating a “general evaluation or feeling of favorableness toward the object in question” (p. 493). Fishbein and Ajzen suggest that the term ‘attitude’ should be reserved solely to refer to a person’s location on the affective dimension concerning a particular attitude object. The evaluative nature of attitudes is reflected by many types of attitude measurement that focus on a person’s rating on ‘like-dislike’, ‘agree-disagree’, ‘favourable-unfavourable’, ‘good-bad’ or ‘approve-disapprove’ scales. Some of the best known examples of such attitude scales are those developed by Thurstone, Guttman and Likert.[ii]

Stressing the evaluative nature of attitudes, a widely accepted definition of the concept is: (…) a learned predisposition to respond in a consistently favorable or unfavorable manner with respect to a given object (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975, p. 6).

However, as Ajzen pointed out years later (1988), attitudes, though still primarily reserved for the affective dimension, may also be inferred from expressions of beliefs (i.e., cognition) about the attitude object and expressions of behavioural intentions (i.e., conation) toward the attitude object (Ajzen, 1988). In fact, as Hogarth argued, the word ‘evaluative’ in the definition already implies both a belief (cognition) about an object and an emotional response (affect) to it (Hogarth, 1971). From an operational point of view, this seems to be the most manageable approach to the attitude concept and as such it will be endorsed in this study.

The essence of the definition is that an attitude is learned (through experience, education, social and cultural environment), is evaluative in nature and has a motivational function with respect to behaviour. Furthermore, ‘attitude’ is a theoretical construct that has to be inferred from measurable responses toward an object (Ajzen, 1988, p. 4). Attitude objects may be things, places, persons, events, concepts or ideas (Oostveen

& Grumbkow, 1988).

In the present context the adjective ‘penal’ refers to the attitude object of interest to this book. Thus, in general, we are concerned with the study of attitudes with respect to punishment. In particular, our interest lies in scrutinising the link between moral legal theories of punishment and the practice of punishment. To further this endeavour, the attitude object(s) have been further restricted to the central concepts of the theories of Retributivism, Utilitarianism and Restorative Justice.

3.3 Why measure penal attitudes?

It has been argued, from a moral point of view, that theories can and should bind the practice of punishment to certain order and regularity (see Chapter 2). Moral theory of legal punishment is expected to serve as a critical standard for the practice. In other words, we would expect our practice of punishment to reflect a solid underlying legitimising framework. Officials within the criminal justice system frequently tend to justify their institution and the concrete practice of punishment by referring to legitimizing aims and values drawn from moral theories of punishment (Duff & Garland, 1994). Accordingly, the evident moral worth of philosophies and theories of punishment leads one to expect a consistent link between theory and practice. Closer inspection of sentencing practice, however, suggests that, although a link between (moral) theory and practice may well be present, it is not as evident and straightforward as one might expect or wish. As Tunick has put it:

I believe there is an ideal of justice underlying our practice of legal punishment, an ideal that sometimes gets obscured, lost in the shadows of the institutions of criminal law (Tunick, 1992, p. viii).

At an aggregate level, overlooking longer periods of time, autonomous dynamics seem to underlie the sentencing process. Such dynamics, however, appear to be independent of the offences committed or the social context in which the system is operating (Michon, 1995; Michon, 1997). Furthermore, even though such dynamics may be demonstrated, they do not necessarily reflect underlying legitimising views about functions and goals of punishment.

At the more specific level of concrete sanctions in individual cases or in groups of similar cases, the quest for consistent underlying views concerning justification and purpose is perhaps even more complicated. At this level research has repeatedly shown substantial differences between individual judges and between district courts concerning sentencing decisions in similar cases (Berghuis, 1992; Fiselier, 1985; Grapendaal, Groen, & Van der Heide, 1997; Kannegieter, 1994). Furthermore, it proves to be especially difficult to infer underlying purposes or philosophies of punishment from the actual practice of sentencing (Myers & Talarico, 1987).

This is especially true in instances concerning the relation between offence seriousness and severity of punishment. For instance, with rehabilitation in mind, the more serious the offence, the more deviant the offender’s personality is supposed to be, and therefore the longer the offender must be detained in order to rehabilitate. A similar relation between offence seriousness and severity of punishment holds for deterrence, incapacitation, and retribution (Fitzmaurice & Pease, 1986, pp. 49–51; Pease, 1987). Most sentences can be argued a posteriori to have had the intention of serving any combination of purposes or any purpose exclusively (cf. Van der Kaaden & Steenhuis, 1976). As such, one might even argue that moral legal theory concerning punishment merely serves as a convenient pool of rationalisations that can be drawn from eclectically (cf. Van der Kaaden, 1977).

Even if all judges would be completely consistent (within and between themselves) in their sentencing practices, it would still be impossible to infer an underlying philosophy solely from the sentences passed. Additional (external) statements concerning purposes of punishment would be helpful.[iii] One might expect to find such guiding principles in the Penal Code. In Dutch Penal Code, however, no such information is to be found (Hazewinkel-Suringa & Remmelink, 1994; Nagel, 1977; Van der Kaaden, 1977 ). Neither a general justification, nor purposes at sentencing are provided in the Dutch Penal Code.[iv] But even if ‘rationales for sentencing’ (Council of Europe, 1993) were to be formalised, the mere existence of such reasoned expositions is not enough to guarantee their adoption by sentencing judges, nor can examination of sentences establish whether they have been applied consistently.

Thus, if we are to study the link between moral legal theory and the practice of punishment, the measurement of judges’ penal attitudes is an inevitable prerequisite. We need to be able to measure penal attitudes in a manner consistent with moral legal theory. If there is a legitimising (moral) view or framework underlying the practice of sentencing today, it should somehow be reflected in the minds of the sentencing judges. If a general justification and purposes of punishment were prescribed in Dutch Penal Code, we could ‘simply’ check if judges’ attitudes reflect such prescriptions. In the absence of both formal prescriptions and guiding principles, it is therefore important to measure judges’ attitudes and to search for communal moral points of view with possible implications for sentencing. The first necessary step is to establish that the various theoretical arguments and concepts have some meaning whatsoever in the minds of magistrates. Second, we would have to decide whether judges’ understanding of those concepts reflects a consistent, relevant and legitimising perspective of justice for the practice of sentencing.

In summary, moral theories can only ‘bind’ the practice of punishment if the officials involved in the practice know of, understand, and adopt (at least parts of) those theories. The notion of ‘penal attitudes’ must be central in any study concerning the link between moral theory and practice. The measurement of penal attitudes will play a critical role not only in establishing the link between moral theory and practice of punishment, but also in assessing implications for legislative change and policy implementation (Bazemore & Feder, 1997). For example, in order to encourage more consistency in sentencing, sentencing committees within the Dutch judiciary are currently coordinating the formulation of ‘starting points’ in sentencing. Such a system of starting points, however, presupposes the existence of an underlying vision (Lensing, 1998). Detailed knowledge about the visions of Dutch magistrates may determine the success and acceptance of such starting points. It is conceivable that judges interpret and validate goals and means of sentencing in different ways. If we want to harmonise such differences, we need to be able to explicitate them objectively (Van der Kaaden, 1977). Furthermore, longitudinal assessment of penal attitudes, as well as their measurement among different professional groups (e.g., prosecutors, probation officers) may be of crucial importance for shedding light on some of the fundamental dynamics underlying our criminal justice system.

3.4 Approaches to the measurement of penal attitudes

This section provides a brief review of a number of approaches to the measurement of penal attitudes. The specific definition of our attitude object (as described in Section 3.2) will be relaxed in order to allow us to draw examples from a wider range of research experiences.

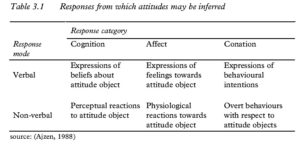

In Section 3.2 it was argued that ‘attitude’ is a theoretical construct. As such, attitudes are not open to direct observation. Instead, attitudes have to be inferred from peoples’ responses to attitude objects. Such responses are believed to be expressions of attitude (De Vries, 1988). These expressions may be verbal or non-verbal in nature and, in general, are measurable. Table 3.1 shows the types of measurable responses towards objects from which attitudes may

thus be inferred. The table was extracted from Ajzen (1988, p. 5). Because attitudes have to be inferred from verbal or non-verbal expressions, concerns for reliability and validity of the measurement abound. We will pay due attention to such concerns. Although Table 3.1 shows the various types of responses from which attitudes can be inferred, methods for measuring those responses may vary within and across the cells. A particularly useful and important general distinction between measurement methods is one which considers differences between qualitative and quantitative approaches to attitude measurement.

Qualitative approaches to attitude measurement generally focus in depth on relatively few cases. “It goes beyond how much there is of something to tell us about its essential qualities” (Miles & Huberman, 1984, p. 215). Qualitative research methods include unstructured or semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions (Rubin & Rubin, 1995), think-aloud protocols (Ericsson & Simon, 1984; Newell & Simon, 1972), group interviews and conversation analysis (e.g., focus groups: Morgan (1993)), observations of overt behaviour and content analysis of documents or transcripts. These methods produce data in the form of words rather than numbers (Miles & Huberman, 1984). Although some level of quantification (coding) is not uncommon in qualitative research, in general it does not rely on statistical methods of inference. Rather the qualitative researcher emphasises in-depth interpretation of the often detailed qualitative data at hand (Swanborn, 1987).

Quantitative approaches, on the other hand, focus on relatively large numbers of cases. They are aimed at producing quantitative or easily quantifiable data. Quantitative research methods generally involve the use of (inferential) statistics in order to search for or test common and generalisable patterns of association or causation. Quantitative approaches to attitude measurement usually concern extensive use of uni- and/or multidimensional scaling techniques with data obtained through questionnaires.

Scaling methods are used to scale persons, stimuli or both persons and stimuli (McIver & Carmines, 1981). One of the most widely used unidimensional scaling methods is Likert scaling (Likert, 1970; McIver & Carmines, 1981; Swanborn, 1988). A Likert scale produces a single score for a person representing his or her degree of favorableness toward a particular object. Some other well-known unidimensional scaling techniques are Guttman scaling and Coombs scaling (cf. McIver & Carmines, 1981; Summers, 1970; Swanborn, 1988). In contrast with the Likert scale, which is subject (i.e., person)-centered, the scales developed by Guttman and Coombs produce scale values (on one continuum) for both persons and stimuli. Of course, the choice of method should depend on the research questions. In contemporary attitudinal research, however, most researchers seem to prefer the use of Likert scales. Likert scaling procedures are relatively simple, easy to use and generally appear to produce results at least as reliable as the other, more complex methods.

Multidimensional scaling techniques involve the simultaneous assessment of respondents’ positions vis-à-vis more than one latent trait (i.e., dimensions). Furthermore, ultidimensional methods, such as Principal Components Analysis (Dunteman, 1989), Factor Analysis (Kim & Meuller, 1978; Kim & Mueller, 1978), Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) (Kruskal & Wish, 1978), HOMALS and PRINCALS (Gifi, 1990; Van de Geer, 1988) may be used to determine the dimensionality underlying responses to a set of items. In other words, they are used to determine the number and composition of empirically (and preferably theoretically) discernible latent traits in a particular set of data. As such, in empirical research, multidimensional methods frequently precede unidimensional scaling in order to determine how many and which attitude scales should be constructed as well as which items should be included in those scales.

Before elaborating on some examples of different approaches to attitudinal research in a judicial setting, one more methodological issue regarding certain types of attitude measurement needs to be addressed. As mentioned above, concerns for reliability and validity abound in any type of attitude measurement. Moreover, ‘single item measures’ of attitude are especially prone to problems of reliability and validity. Although such single item scales are frequently referred to as ‘Likert-type scales’, they should not be confused with attitude scales obtained through the Likert procedure, which involves summation of multiple items.[v] In single measures of attitude, respondents are asked to report directly on the attitude of interest using a single scale for favorableness or agreement. A single measure can never fully represent a complex theoretical construct. Rather, such a single measure simply captures part of that construct. This is a matter of validity. Furthermore, single measures tend to be unreliable: repeated measurements are not as highly correlated as one might expect or wish.

This is due to random error in measurement. In multiple item scales, the random errors involved in the separate items are assumed to cancel each other out through the combination procedure, yielding a much more reliable final scale. Although most methodologists agree that multiple item scales are superior to single item scales (McIver & Carmines, 1981; Nunnally, 1981), single item scales are still widely used.

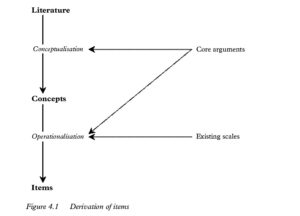

Apart from, but related to, methodological issues in scaling, the researcher interested in a particular attitude must decide on how to select or derive the items (attitude statements) that will be used for the measurement. Again, different approaches are possible. Among these are eclectic or pragmatic approaches, theory driven approaches and phenomenological approaches. Below, a number of research experiences with attitude measurement in a judicial setting are discussed to illustrate different approaches.[vi]

3.4.1 Quantitative research

Multiple measures

One comprehensive and well known quantitative study of the sentencing process is Sentencing as a Human Process by Hogarth (1971). Magistrates’ attitudes play a central role in this frequently cited study. Given the impact Hogarth’s study had in this field of research as well as the systematic and well documented methodology he applied, we will give it more attention than several other studies.

Confronted with substantial disparity in sentencing in Ontario, Canada in the 1960’s, Hogarth set out to examine and explain the sentencing process among Canadian magistrates. He distinguished between three main classes of independent variables: variables related to the cases dealt with, legal and social environment (constraints), and personality and backgrounds of the magistrates (Hogarth, 1971, p. 18). In considering the personality of magistrates, Hogarth chose to focus on ‘larger psychological units’, i.e., attitudes. He argued that attitudes represent “a compromise between inner forces of individual magistrates and their definitions of the external world to which they relate” (p. 24). As such, he conceived attitudes as information-processing structures (p. 101). Hogarth’s definition of the concept attitude is quite conventional and concurs with our view of the concept discussed in Section 3.2 above. His attitude object, however, is much more widely defined. Hogarth considers judicial attitudes. Judicial attitudes include all attitudes relevant to the judicial role which the individual magistrate has adopted.

In determining the method of attitude measurement, Hogarth argued against inferring judicial attitudes from judicial conduct (i.e., overt behaviour) because that would lead to circularity in reasoning when explaining the behaviour. Instead, he chose to construct attitude scales through specifically designed questionnaires. Hogarth’s approach to the selection of attitude statements (items) that are used for scale construction is phenomenological.

This approach can be contrasted with the theoretical approach to item selection in which items are logically derived from existing theories on the subject. In the theoretical approach, “the researcher makes a priori theoretical assumptions about the existence of certain attitudes held by the subjects of investigation” (p. 103). In the phenomenological approach, on the other hand, items are selected from evaluative statements made by the subjects of investigation themselves. The phenomenological sources of evaluative statements which Hogarth used include sentencing principles stated by magistrates in reported cases, articles published by magistrates, reports of study groups, decisions of courts of appeal and speeches by judges related to crime and punishment (p. 107). The pool of attitude statements thus obtained was narrowed down in the course of three pilot studies involving various types of subjects such as students, police officers, and probation officers.

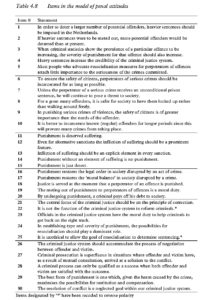

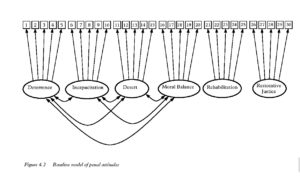

For his main study, Hogarth selected a sample of 116 probation officers, 103 police officers, 50 law students, 59 social work students, and 73 magistrates. He used Principal Components Analysis with orthogonal (varimax) rotation of the components to derive attitude scales from a pool of 107 items. Five rotated principal components emerged from the analysis, explaining almost 60 percent of the total variance in responses. The first component is labelled justice. It covers items that seem related to the concern that crime be punished in proportion to its severity (just deserts).

The second component is labelled punishment corrects and involves items related to individual prevention through treatment and individual deterrence. The third component is labelled intolerance and involves items not directly related to crime, but, rather, social deviance in general. The fourth component is labelled social defence and involves items related to general deterrence and denunciation of crime. The fifth and final component is labelled modernism and relates to ‘new-world’ puritanism versus values associated with the modern welfare state. It involves items concerning the use of alcohol, crime, need for self-discipline and antagonism to social welfare measures (p. 129).

Although Likert scales analogous (in terms of items) to the five components turn out to be quite reliable (split half reliability), the rotated principal components had better predictive value regarding the Canadian judges’ sentencing behaviour. This finding was obtained through regression analyses. Before drawing any definite conclusions about the impact of judicial attitudes on judges’ sentencing behaviour, Hogarth’s analyses proceeded with including variables related to the cases dealt with, and legal, social and situational constraints. Results showed sentencing by Canadian magistrates

(…) as a dynamic process in which the facts of the cases, the constraints arising out of the law and the social system and other features of the external world are interpreted, assimilated, and made sense of in ways compatible with the attitudes of the magistrate concerned (Hogarth, 1971, p. 343).

These findings concur with Hogarth’s view of attitudes as important information-processing structures. Although the judicial attitudes themselves may not be the most important single factor determining the outcome of a sentencing process, they play an important role in the way judges perceive (filter) the world around them (p. 367).

Hogarth was among the first to systematically analyse the sentencing process in a quantitative manner using a wide range of independent variables including judges’ attitudes. Although criticisms regarding some of the methods are possible[vii], the study had considerable impact and served as an important impetus for future research.

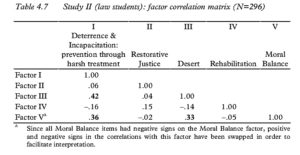

Examples of more recent studies in which similar quantitative approaches to the measurement of (penal) attitudes were used, include those carried out by Carroll et al. (1987) and by Ortet-Fabregat and Pérez (1992). Carroll et al. set out to find coherent patterns of association (‘resonances’) among sentencing goals (‘penal philosophies’), causal attributions, ideology and personality. They described two studies: one with law and criminology students and one with probation officers, both in Chicago, U.S. They factor-analysed a pool of 104 sentencing goal items.[viii] Three meaningful factors emerged from the analysis:

satisfactory performance of the criminal justice system, punishment (harsh treatment) and rehabilitation.

Subsequently, for further analyses, the highest loading items were selected for inclusion in summated rating scales (i.e., Likert scales).

The same procedure was applied to construct scales for attributions of crime causation, ideology and personality. For both students and probation officers, further analyses indicated two types of coherent patterns among the variables. The first revealed a conservative and moralistic pattern: a punitive stance toward crime; belief in individual causes of crime; lower moral development of offenders; authoritarianism; dogmatism; and political conservatism. Carroll et al. viewed the second pattern as being more liberal in nature: rehabilitation; deterministic view on causes of crime; higher moral development of offenders; and belief in the powers and responsibilities of government to correct social problems (Carroll et al., 1987).

Ortet-Fabregat and Pérez (1992) discussed two studies aimed at describing and comparing attitudes of different types of professionals within the criminal justice system in Catalonia, Spain toward causes, prevention and treatment of crime. The first study used a sample of students, while the second study used rehabilitation teams and social workers from prisons, prosecutors, judges and lawyers, corrections officers and police officers. The main purpose of the first study was to develop scales measuring the attitudes towards causes of crime (cf. Carroll et al., 1987), prevention, and treatment. The authors’ approach to the selection of items was eclectic, theoretical and phenomenological. They eclectically obtained items from existing attitude scales (e.g., Brodsky & Smitterman, 1983), theoretically from scientific literature about the topics and phenomenologically from communication with professionals in the criminal justice system. Causes of crime were represented by 22 items, prevention by 25, and treatment by 22. Each set of items was separately analysed using Principal Components Analysis with orthogonal rotation. Two principal components appeared to underlie attitudes toward causes of crime: hereditary and individual causes, and social and environmental causes. Analysis of the prevention items also resulted in two components: coercive prevention and social intervention prevention. Analysis of the treatment items resulted in one substantive underlying component, which was labelled assistance versus punishment. Analogous summated rating scales (i.e., Likert scales) were constructed for subsequent use in the second study with criminal justice professionals. The second study aimed at describing and comparing mean scores on the attitude scales between the various professional groups in the sample. Results indicated that, overall, a social and rehabilitation approach to the causes, treatment and prevention of crime was favoured (Ortet-Fabregat & Pérez, 1992). Apart from this overall impression, any differences found were in the directions that could be expected considering the different professional roles of the groups. For instance, rehabilitation teams and social workers from prisons were less favourable towards coercive prevention and more favourable towards social intervention prevention than were law enforcement officers.

Single measures

Single measures generally focus on concrete sentencing goals, such as rehabilitation, retribution and deterrence. Respondents are either asked to indicate their favourableness toward the concepts on separate rating scales or requested to rank a number of sentencing goals. Some of the studies concern ratings for sentencing goals in general whilst others relate to specific cases. Examples of studies in which such measurement procedures are used include those carried out by Forst and Wellford (1981), Henham (1990), and Bond (1981).

To provide an empirical foundation for the formulation of sentencing guidelines for the federal court system in the U.S., Forst and Wellford carried out an extensive survey on the goals of sentencing and perceptions of sentencing disparity. They conducted interviews with 264 federal judges, 103 federal prosecutors, 110 defence attorneys, 113 probation officers, 1248 members of the general public, and 550 incarcerated federal offenders (Forst & Wellford, 1981). Respondents were asked to rate the importance that they in general attached to general deterrence, special deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and just deserts on five-point scales. In order to improve validity of the measurement, all respondents were first provided with definitions of these concepts. Judges were also asked about the severity of their sentences when, for a given case, they had a specific sentencing goal in mind. Furthermore, the general ratings for the sentencing goals were used to explain judges’ sentencing decisions in 16 hypothetical cases. Results indicated that among judges general and special deterrence were found to be especially important, followed, in decreasing order of importance, by incapacitation, rehabilitation and just deserts. Prosecutors and probation officers also found deterrence and incapacitation more important than rehabilitation and just deserts. Among defence attorneys and prison inmates, rehabilitation received strongest support. Judges indicated that rehabilitation, if intended, clearly makes a sentence more lenient. Using the hypothetical cases, with length of the prison term as dependent variable, regression analyses showed that judges’ perceptions of the goals of sentencing could explain 40 percent of the variance.

Henham (1988; 1990) examined English magistrates’ sentencing ‘principles’ as well as their sentencing behaviour. Henham interviewed 129 magistrates using structured questionnaires. He asked the magistrates to rate the general sentencing objectives of reformation, punishment, general deterrence, individual deterrence and protection of society on five-point scales.[ix] Furthermore the magistrates were asked to select a particular sentencing objective for each of five hypothetical criminal cases. Results showed that, in general, English magistrates attached greatest importance to protection of society, followed by, in decreasing order of importance, individual deterrence, general deterrence, punishment and reformation. Correlations between these ratings led Henham to speculate that magistrates find it difficult to discriminate amongst the various objectives (p. 115). However, this may well be due to error resulting from Henham’s measurement method (i.e., single measures). Furthermore, magistrates appeared to be consistent in terms of the general and case specific views that they hold themselves. However, contrary to Hogarth’s findings, Henham found no evidence to “support the view that penal philosophy is a particularly important mechanism in the selective perception of information regarding legal constraints by sentencers” (Henham, 1990, p. 151).

Bond and Lemon (1981) carried out a study among 157 English magistrates to determine the effect of experience and training on importance attached to sentencing objectives and sentencing behaviour. Respondents were asked to give a general rating of importance for individual deterrence, general deterrence, reformation, retribution, and protection of society. Subsequently for eight hypothetical cases, judges were requested to indicate the appropriate sentence. Results indicated that as a result of experience, magistrates became less inclined to perceive their role in sentencing as one concerned with reformation of offenders and more inclined to see it as concerned with deterrence and protection of society. Furthermore, increasing experience leads to less sympathetic views of offenders (p. 133). Training, which magistrates receive on the bench, appeared to moderate these effects.

Apart from measuring favourableness toward certain sentencing goals with rating scales, several other methods have sometimes been used. Some researchers asked respondents to mention the goal(s) they aim to achieve with a sentence either in a general sense, or in the context of a specific case. An example of such an approach is Kapardis’ research.[x] Kapardis (1987) used nine cases with 168 English magistrates. Judges were asked to pass sentence and indicate which goal(s) they wanted to achieve. The most frequently stated aim among magistrates was individual deterrence, followed by punishment, reform, protection of society, general deterrence, denunciation and reparation. However, widely different sentences were sometimes given in the same case and with the same penal aim in mind.

Kapardis found no consistency between judges’ penal philosophies (in terms of sentencing objectives) and punitiveness in sentencing behaviour (p. 198). A second example of a study concerning judges in criminal courts using other methods than rating scales, is the study carried out by Bruinsma and Van Grinsven (1990). Although this study was not directly focused on measuring individual penal attitudes it is an exception to the general lack of quantitative studies in the Netherlands in this area of research. Bruinsma and Van Grinsven chose abstract sentencing goals as the starting point of their analyses. Propositions were deduced from these sentencing goals. For instance, concerning the sentencing goal of general prevention, the deduced proposition was: ‘The more serious the offence, the harsher the punishment’ (Bruinsma & Grinsven, 1990, p. 136). In order to empirically test these propositions, Bruinsma and Van Grinsven transformed them into decision rules, incorporating case- and offender characteristics. Assuming that the amount of material damage is a good indicator for seriousness, the resulting decision rule for the above proposition was: ‘The greater the material damage caused by the offence, the harsher the punishment’ (p. 136). The researchers realised that if they found empirical confirmation for the decision rules, it would not necessarily imply that the ‘underlying’ sentencing goals had indeed been aimed for.

This is due to unavoidable difficulties involved in inferring underlying purposes from the actual practice of sentencing discussed in Section 3.3. Instead, they argued that failure to empirically confirm a decision rule does merit the conclusion that the underlying sentencing goal had not been applied. In the above manner, propositions and decision rules were deduced from a number of sentencing goals. Bruinsma and Van Grinsven tested their decision rules using a random sample of 1210 cases heard by police judges at district courts in the Netherlands. Results indicated that Dutch police judges are only to a limited extent guided by the decision rules that were deduced from sentencing goals.

3.4.2 Qualitative research

In this section we will discuss examples of qualitative research carried out in the Netherlands. The reason for this decision is that research on attitudes among Dutch criminal justice officials in general, and judges in particular, is very scarce (Frijda, 1996; Van Duyne & Verwoerd, 1985; Van Koppen, Hessing, & Crombag, 1997). In so far as Dutch research directly or indirectly involved (penal) attitudes, views or opinions, it has been predominantly qualitative in nature. The methods used involve interviews, dossier and protocol analysis, discussion groups, and participant observation. As such, this section not only illustrates relevant methods of qualitative research, but also outlines the general state of affairs of such research in the Netherlands. The studies discussed include those carried out by Enschedé et al. (1975), Van der Kaaden and Steenhuis (1976), Van Duyne (1983; 1987), Van Duyne and Verwoerd (1985), Kannegieter and Strikwerda (1988), and Kannegieter (1994).

From 1952 until the end of 1954, Enschedé kept systematic notes of the cases he heard as a police judge[xi] in the District Court of Rotterdam. His notes on 244 cases of theft in the Rotterdam harbour area were later analysed by Moor-Smeets (Enschedé et al., 1975, pp. 25–58). Because Enschedé found it difficult to motivate his sentences in more than superficial terms and frequently lacked the time to register his motivation, analysis of the reasons for the sentences was seriously impaired. However, perusal of the sentences passed in relation to characteristics of the offences, together with a general disregard for characteristics of offenders, led Moor-Smeets to speculate that Enschedé’s point of view was more likely to be general preventive in nature than special preventive (p. 41).

Following the analyses by Moor-Smeets, Swart (Enschedé et al., 1975, pp. 59–93) attempted to concentrate in greater detail on judicial views and opinions on sentencing. He combined two methods of investigation.

First, subjects were asked to pass sentences in nine versions of a hypothetical theft case. Participants were also asked to motivate their judgement.

Second, after passing and motivating the sentences, participants discussed their decisions and views with each other. Eleven such sessions were held in ten different districts in the Netherlands, with a total of 162 participants. Most participants were members of the judiciary (judges and prosecutors). Results indicated substantive variation in sentencing decisions and motivations within each version of the case. Since participants received the same hypothetical cases, Swart points to personality characteristics of participants as the most probable cause of this variation (p. 81).

With reference to Hogarth’s research findings, Swart speculates about the selective perception and interpretation of case characteristics by participants as a result of their personal views (p. 62, p. 82). However, incompleteness and superficiality of the written motivations provided by (only half of the) participants offered only fragmentary insight in such factors. In discussing the cases, participants showed clearly differing opinions on sentencing objectives. In each case, a wide variety of objectives was endorsed by different participants. Moreover, participants seemed to lack a common frame of reference for discussing sentencing objectives with each other. Furthermore, participants who had different objectives in mind passed the same sentence, while participants with the same objectives in mind passed different sentences (p. 83). The general impression emerging from these analyses was not one that conforms to the idea of sentencing as a rational, goal-orientated practice.

Van der Kaaden and Steenhuis examined prosecutors’ views and behaviour in the Arnhem jurisdiction[xii], the Netherlands (Van der Kaaden & Steenhuis, 1976). The first stage in their research involved a questionnaire in which participants were asked to determine and motivate a sentence in two (real) robbery cases. Subsequently, after inventarisation of responses, discussion groups were organised with the prosecutors in each district in the region. In the discussion groups, participants were asked to explain their sentencing decisions and motivations. The prosecutors were encouraged to comment on each other’s responses. Results showed large variations in sentencing demands in both cases. For instance, in one of the cases, decisions varied from dismissal up to 12 months unconditional imprisonment with a compulsory hospital order. These differences could not be attributed to different views on sentencing objectives. As in Swart’s analysis, participants who had the same objectives in mind passed different sentences while participants who had different objectives in mind passed the same sentence. Because the meaning of the various sentencing objectives was obviously interpreted very differently by different prosecutors, a second round of discussions was organised. This time, the meanings of the objectives retribution, special and general prevention, affirmation of norms, and conflict resolution were extensively discussed. Confusion about the meaning of these concepts abounds. Like Swart, Van der Kaaden and Steenhuis conclude that sentencing does not appear to be a very rational practice. Rather, in essence, sentencing appears to be a highly personal matter (p. 19–20).

Van Duyne carried out two observation studies, one with prosecutors (1983; 1987), the other with judges in the plural chamber of a district court (1987; 1985). In order to gain more insight into the decision making processes of prosecutors, Van Duyne focussed on seven prosecutors at the District Court Alkmaar, the Netherlands. He asked them to think aloud while handling ten real cases. Van Duyne found the decision making processes of the prosecutors to be less complicated than expected. The decision making appeared to be one-dimensional: prosecutors selected only those characteristics of a case for consideration which were consistent with a particular ‘dimension’. Examples of such dimensions are ‘professionalism’, ‘social misfit’ or ‘rehabilitation’ (Van Duyne, 1987, p. 147).

Despite this ‘simple decision making’, large discrepancies were found in sentencing demands in each case. Reasons for these discrepancies, Van Duyne argued, include the fact that prosecutors may differ substantially in their choices of the dimensions, in the weights attached to the selected characteristics of a case and in their opinions about proper punishment (Van Duyne, 1987, p. 147). Furthermore, unless specifically requested, very few prosecutors mentioned sentencing objectives. When asked specifically, retribution and prevention were the most frequently mentioned sentencing objectives. According to Van Duyne the fact that most prosecutors did not initially mention sentencing objectives should not be taken to imply that such objectives are irrelevant: purposeful action does not necessarily require decision making with prominent and clearly formulated objectives in mind (Van Duyne, 1983, p. 189). Sentencing objectives, Van Duyne concluded, do play an important role, but this is at a more implicit level and only among a wide range of individual variables related to perceptions of the working environment and task conception.

Through participant observation,[xiii] Van Duyne and Verwoerd (Van Duyne, 1987; 1985; Verwoerd, 1986) examined the collective decision making processes in a panel of judges sitting at one of the district courts in the Netherlands. They attended deliberations in chambers and later analysed 27 transcripts. Punishment objectives such as rehabilitation, retribution or deterrence were seldom mentioned explicitly in the deliberations. Moreover, the decision making seemed very casual to the extent that one of the researchers compared it to haggling in the marketplace (Van Duyne, 1987). No indication was found between sentencing objectives perceived by judges and their actual sentencing behaviour (Verwoerd, 1986). However, the absence of overt verbal statements and discussions pertaining to sentencing objectives does not necessarily imply such considerations to be unimportant for the individual judges (cf. De Keijser, 1999; Van den Heuvel, 1987).

Kannegieter and Strikwerda (Kannegieter, 1994; 1988) set out to examine disparity in sentencing in minor criminal cases. They focused on public prosecutors’ and judges’ views on sentencing. In 1987 they interviewed 18 prosecutors and 17 police judges in the district courts of Leeuwarden, Groningen and Assen, the Netherlands. In the first part of the interview, respondents were asked to demand (prosecutors) or pass (judges) a sentence on a written case that they received some time before the interview. Some information pertaining to personal characteristics of the offender was omitted in the case dossier in order to determine the relative importance of such factors. The additional information was only given if a participant asked for it. After participants had made their decision, they were asked to motivate it. Results showed a great deal of variation in decisions on this one case. The type and severity of punishment could not be consistently related to sentencing objectives. Answers to questions about sentencing objectives were given in very superficial terms. In general, however, there seemed to be agreement that special prevention was the main objective in their sentencing decisions. Despite such agreement on the main general goal, means to attain that goal were viewed very differently (Kannegieter & Strikwerda, 1988, pp. 60–61). Furthermore, almost half of the judges stated their scepticism about the realisation of sentencing objectives.

3.4.3 Some final remarks

In summary, a number of widely used quantitative and qualitative approaches to the measurement of attitudes, opinions or views in judicial settings have been discussed. Most of the studies were aimed at explaining sentencing behaviour using psychological (attitudinal) characteristics of the sentencer. The findings of these studies seem to vary as much as the sentencing behaviour that most researchers report. In this chapter, the studies discussed were used mainly as examples of different measurement approaches. However, even if we had carried out an exhaustive literature review, given the wide variety of methodologies and types of respondents, it would have been extremely difficult to draw general conclusions. Perhaps a meta-analysis (cf. Mullen, 1989; Rosenthal, 1984) of such studies would provide some more general insights. Such a meta-analysis would require coding of variables such as research method, type and number of respondents, types of cases used, year of research and country of research. Concerning the Dutch situation, there is one aspect that seems to emerge from all the qualitative research reviewed. This concerns the confusion or disagreement among criminal justice officials about the meanings of various sentencing objectives as well as the researchers’ inability to find consistencies between sentencing philosophies and sentencing behaviour.

Despite such findings, most authors still allot an important role to the personal views of sentencers. Frequently this is done in a way similar to Hogarth, by stating that psychological characteristics determine the way in which people perceive and interpret the world around them. Concerning the views of the participants in the different studies, one cannot escape the impression that opinions about goals and functions of punishment are not very relevant or interesting to them. Of course this does not necessarily imply that such attitudes or opinions are absent or do not play a role in a less obvious or indirect manner.

NOTES

i. For a detailed critical discussion of the separate elements in Allport’s definition of attitude, see McGuire (1969).

ii. See Summers (1970) and Fishbein (1967) for these and other scaling techniques.

iii. In 1993, the Council of Europe has strongly recommended its member states to explicitly express ‘sentencing rationales’ in their Penal Codes in order to reduce inconsistency in sentencing (cf. Council of Europe, 1993). These recommendations reflect a firm believe in the relevance and impact of theoretical and philosophical concepts for the practice of sentencing.

iv. For a critical discussion on the absence of justification and purposes of sentencing in Dutch Penal Code, see Nagel (1977, pp. 30-40). See also Walker (1985, pp. 105-106) who critically argues that many penal statutes’ silence on the purposes of punishment is deliberate and has political reasons.

v. The term Likert-type scale is frequently used for the method of scoring, implying (usually) a five-point scale ranging from ‘completely agree’ to ‘completely disagree’. Furthermore, an integral part of the Likert procedure is determining internal consistency of the summated scale through item analysis.

vi. Preparatory work carried out by I. Bakker has been very helpful as the basis for the following sections. See Bakker (1996).

vii. For instance, one might argue that Hogarth’s phenomenological approach for deriving attitude scales involves a circular aspect. The scales were derived from evaluative statements of the same population to which they are applied. Furthermore, orthogonal rotation of the principal components yields uncorrelated scales: such orthogonality is artificial and may not do justice to meaningful and important correlation between particular attitudes.

viii. How exactly this pool of items was obtained, remains unclear. The authors mention that the items were selected from a larger pool of items which was written to reflect the dimensions under study (Carroll et al., 1987, p. 110).

ix. Henham used and adapted Hogarth’s purposes of sentencing (Henham, 1990).

x. A similar approach was chosen by Ewart and Pennington (1987).

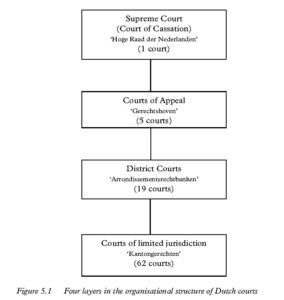

xi. See Section 5.2 for an introduction to the organisation of Dutch criminal courts.

xii. That is, ‘Hofressort’ Arnhem: see Section 5.2.

xiii. One other example of research with participant observation in a judicial setting is Van de Bunt’s research (1985) on decision making by public prosecutors in the Netherlands.