Punishment And Purpose ~ Summary And Conclusions

The fact that a practice exists does not automatically imply that it is, or can be, consistently justified in its given form (even if this may have been the case in the past). The practice of punishment, it has been argued, is a morally problematic practice and therefore needs a consistent (moral) justification. The present study explored the justification of the Dutch practice of punishment from one particular perspective. The aim of the study was to determine whether or not a consistent legitimising framework, either founded in or derived from moral legal theory, underlies the institution and practice of legal punishment in the Netherlands.

The fact that a practice exists does not automatically imply that it is, or can be, consistently justified in its given form (even if this may have been the case in the past). The practice of punishment, it has been argued, is a morally problematic practice and therefore needs a consistent (moral) justification. The present study explored the justification of the Dutch practice of punishment from one particular perspective. The aim of the study was to determine whether or not a consistent legitimising framework, either founded in or derived from moral legal theory, underlies the institution and practice of legal punishment in the Netherlands.

In order to investigate the link between moral theory of punishment and the practice of punishment the first step was to explore whether concepts derived from moral legal theory have a meaning for criminal justice officials. Furthermore, it was necessary to explore how these concepts, as utilised by judges, interrelate. The gamut of perspectives concerning the justification and goals of punishment was narrowed down to three main categories: Retributivism, Utilitarianism and Restorative Justice. Retributivist theories are retrospective in orientation. The general justification for retributive punishment is found in a disturbed moral balance in society; a balance that was upset by a past criminal act. Infliction of suffering proportional to the harm done and the culpability of the offender (desert) is supposed to have an inherent moral value and to restore that balance.

Utilitarian theories are forward-looking. Legal punishment provides beneficial effects (utility) for the future that are supposed to outweigh the suffering inflicted on offenders. This utility may be achieved, through punishment, by individual and general deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation and resocialisation, and the affirmation of norms. Restorative justice emphasises the importance of conflict-resolution through the restitution of wrongs and losses by the offender. The victim of a crime and the harm suffered play a central role in restorative justice. The main objective is to repair or compensate the harm caused by the offence.

The central concepts of these three approaches to legal punishment were systematically operationalised as a pool of attitude statements to enable the measurement and modelling of penal attitudes. As a result of two extensive studies involving Dutch law students, this measurement instrument was refined, replicated, and validated. Based on the results of the second study with law students, a theoretically integrated (structural) model of penal attitudes was formulated. Following the two studies with law students, data were collected from judges in Dutch courts. Almost half of all judges working full-time in the criminal law divisions of the district courts and the courts of appeal cooperated with the study. Analyses revealed a number of interesting findings.

In the past it had been asserted that there is much conceptual confusion among Dutch judges as to the meaning of various goals and functions of punishment (cf. Chapter 3). In contrast, the present study shows that the relevant concepts are consistently measurable and meaningful for Dutch judges. In both student samples as well as in the judges’ sample Deterrence, Incapacitation, Rehabilitation (Utilitarian concepts) and Desert and restoring the Moral Balance (Retributive concepts) could be represented by five separate, internally consistent scales. The approach of Restorative Justice could be empirically represented by a single homogeneous attitude scale in all three samples. As such, unlike Retributivism and Utilitarianism, Restorative Justice was the only approach that was reflected by a single dimension and thus appears to offer a more integrated account of punishment than the other approaches. To our knowledge (see literature review in Chapter 3) this is the first study to have successfully operationalised Restorative Justice and to position it empirically amongst the more traditional approaches to criminal justice. It was, however, the factor least supported by judges. An examination of the theoretically integrated model of penal attitudes amongst judges confirmed earlier findings with law students: in three different samples, the two student samples and the sample of judges, (basically) the same structure in penal attitudes was found. Further analyses revealed that instead of mirroring any particular approach or theoretical framework exclusively, the overall structure of Dutch judges’ penal attitudes reflects a streamlined and pragmatic approach to punishment. Two clusters of substantially correlated concepts were identified in judges’ attitudes. These included Deterrence, Incapacitation, Desert, and restoring the Moral Balance on the one hand and Rehabilitation and Restorative Justice on the other. The first set includes concepts generally associated with punitiveness, or, rather, harsh treatment of offenders. The second set involves socially constructive aspects of the reaction to offending. Rehabilitation involves socially constructive aspects of the offender and his position in society, while Restorative Justice is concerned with socially constructive aspects of the victim’s position and the relationship between victim and offender. The fact that Restorative Justice and Rehabilitation turned out to be strongly correlated may seem awkward from a theoretical point of view. After all, an important impetus for the development of the Restorative Justice approach has been a high degree of dissatisfaction with the existing retributive and utilitarian approaches. Two explanations come to mind. First, there is an inclination in the Netherlands to regard restorative aspects as means of helping to bring about behavioural changes in offenders. Second, the Restorative Justice paradigm does not disqualify rehabilitation and resocialisation of offenders. Though not the primary objective, resocialising effects of a restorative intervention are regarded as probable and desirable spin-offs (e.g., Bazemore & Maloney, 1994; Walgrave, 1994; Weitekamp, 1992). In penal practice both views may therefore be regarded as complementary.

Moreover, this empirical finding can be taken as an illustration of how an alternative paradigm (like Restorative Justice) may become incorporated in or perhaps even corrupted by the existing criminal justice system, thus losing its identity as a true alternative paradigm (cf. Levrant, Cullen, Fulton, & Wozniak, 1999). This finding may also lead one to ponder on opportunities for a theoretical integration of Restorative Justice and the utilitarian view of Rehabilitation. However, both views share an important weakness that cannot be resolved by integration. This is the lack of a limiting and guiding negative principle, since both views are quite indifferent to the (unintended) punitive effects of an intervention. Furthermore, since rehabilitation is a likely and beneficial spin-off of restorative actions (perhaps even more so than interventions explicitly aimed at rehabilitation), little is to be gained from such integration. A final note on the association between Restorative Justice and Rehabilitation in the minds of Dutch magistrates relates to our operationalisation of Restorative Justice.

For the purpose of this study we concentrated on a modest (i.e., immanent; see Chapter 2), less radical version of Restorative Justice. A radical version would, with the current group of respondents, presumably have led to Restorative Justice being represented by a dimension much isolated from the other concepts in the study.

In essence, results showed the complex of penal attitudes to be dominated by two straightforward perspectives: harsh treatment (incorporating Deterrence, Incapacitation, Desert, and Moral Balance) and social constructiveness (incorporating Restorative Justice and Rehabilitation). Thus, in terms of general, case-independent penal attitudes, Dutch judges appear not to feel constrained by theoretical incompatibilities or boundaries. One might expect the general perspectives of harsh treatment and social constructiveness to be conflicting. However, these two ‘down to earth’ attitudinal perspectives were found to be uncorrelated. Given this pragmatic general structure of penal attitudes, no systematic and consistent approach or direction is implied regarding the justification and goals of punishment in sentencing practice. Instead, particular characteristics of offence and offender are more likely to determine the value attached to specific goals and justifications of punishment in each and every case. The pragmatic approach that was revealed can be interpreted as an attitudinal structure that reflects or facilitates the strong desire in Dutch sentencing practice to individualise sentences, i.e., to tailor a sentence to the unique aspects and circumstances of specific cases and individual offenders (cf. Chapter 5). We will return to this point shortly.

A limited number of judges’ background characteristics were available for a closer look at judges’ penal attitudes (i.e., court of appointment, age, gender, function within criminal law division of the court, experience in criminal law division, and previous occupation). Gender and years of experience in the criminal law division appeared to be the only characteristics substantially related to individual penal attitudes. Preferences for ‘harsh treatment’ increase with years of experience while, at the same time, support for ‘social construction’ drops. Furthermore, female judges tend to be less favourable towards Incapacitation, Deterrence, and Desert than their male counterparts.

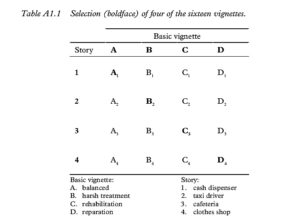

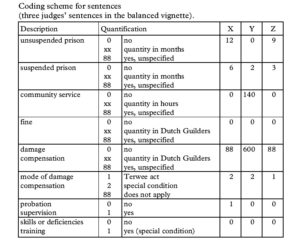

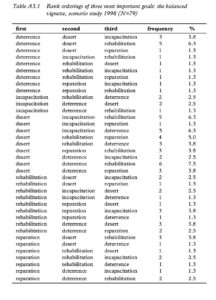

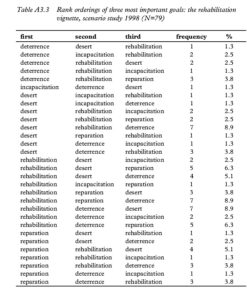

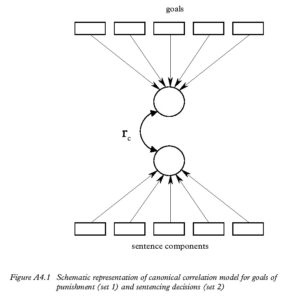

In order to acquire an overall and well-founded impression regarding the link between supposed purposes and justifications of punishment and the actual practice of punishment, it is not sufficient simply to measure and analyse abstract penal attitudes. A necessary further step is to examine the goals that judges pursue in specific criminal cases. In short, the two aspects of interest are abstract notions of punishment on the one hand, and ‘punishment in action’ on the other. Punishment in action was examined by means of a scenario study. This involved presenting judges with four criminal cases (robbery cases) and examining the differences in preferences for goals of punishment and sentencing decisions. The cases employed in the scenario study were based on a selection from a large database of real cases that were heard by criminal courts in the Netherlands. The four cases that were presented to judges differed from one another in terms of the incorporation of pointers (i.e., bits of information) that were expected to evoke preferences for different goals of punishment. As such a ‘balanced vignette’ (equal pointers for deterrence, incapacitation, desert, rehabilitation, and reparation), a ‘harsh treatment vignette’ (dominated by pointers for deterrence, incapacitation, and desert), a ‘rehabilitation vignette’ (dominated by pointers for rehabilitation) and a ‘reparation vignette’ (dominated by pointers for reparation) were created (cf. Chapter 7). The study further aimed to determine whether or not substantial and consistent patterns of association exist between goals and sentences and also the relevance of abstract penal attitudes for pursuing particular goals of punishment in specific cases. Thus, for selected cases, the study was tailored to explore the consistency and relevance of sentencing goals in the light of sentencing decisions rather than to explain sentencing decisions. The scenario study explicitly focused on judges’ penal attitudes and preferences for goals of punishment while, through the experimental nature of the design, controlling as many other factors as possible. A major strength of such a design, in which the same cases are presented to all judges in the study is that, given a particular case, any differences found between judges’ evaluations cannot be attributed to differences in specific case characteristics.

The scenario study showed that, within the same criminal cases, judges’ preferences for goals of punishment varied substantially. Apparently, there is no commonly shared vision among Dutch judges in relation to the goals of punishment that apply in specific cases (at least not with the goals that we have focused upon). A partial exception was the harsh treatment vignette, the most serious case in the scenario study, in which the majority of judges agreed about the relative low level of importance of rehabilitation and reparation as goals of punishment.

The study also showed that judges’ sentencing decisions varied widely in the same criminal cases. Moreover, it was shown that different types of criminal cases with different types of offenders elicit different types of variation in sentencing. In the most serious robbery case in the study (i.e., the harsh treatment vignette) the offender and offence characteristics showed few opportunities for rehabilitation and reparation, as reflected in judges’ preferences for the goals of punishment. While there was little variation among judges in choice of principal punishment (i.e. unconditional prison term), as well as in the choice of special conditions, variation in sentencing in this case manifested itself predominantly in terms of severity, that is, length of the prison term. In the three other vignettes, where opportunities (pointers) for rehabilitation and/or reparation were present, the variation in sentencing decisions was more complex. This was due mainly to variations in choice of principal punishments as well as variations in the use of special conditions with suspended sentences.

While the judges evaluated the cases from the scenario study individually, in practice serious cases are tried by panels of three judges (cf. Chapter 5). In deliberations in chambers, such panels have to reach agreement amongst themselves on the sentence to be passed. To relieve the caseload of panels of judges in the Netherlands, it has been suggested that the competence of police judges (unus iudex) should be increased from six to twelve months imprisonment (cf. Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal, 1998; Van der Horst, 1993). The wide variation in sentencing decisions among individual judges found in this study raises a cautionary note when considering such a change in the system. Before implementing such a change, the effect on sentencing disparity of trying more serious cases by judges sitting alone should be considered very seriously. The mitigating effects of consensus as a result of the deliberations by panels of judges should not be undervalued.[i]

The relationship between preferred goals of punishment and sentencing decisions in the scenario study was examined in order to determine whether or not the variation in both sets of variables was linked in a consistent and substantial manner. Even though, with respect to the same cases, judges may differ amongst themselves, both in terms of their preferred goals of punishment as well as in their sentencing decisions, it is still possible for goals and sentences to be related in a consistent and meaningful way. Overall, results show that preferences for goals of punishment were not very relevant for choosing a particular sanction, nor were sentencing decisions consistently rationalised by goals of punishment. As might be expected, however, the harsh treatment vignette constituted an exception. In this case at best 18 percent of the variance in sentencing could be accounted for by variance in goal preferences. The two sets of variables were clearly associated along the lines of harsh treatment versus social constructiveness.

Regarding the relationship between personal, case-independent, penal attitudes and preferred goals at sentencing, penal attitudes were expected to be of relevance only when pointers for the range of goals of punishment are equally present in a particular case. In the balanced vignette (i.e. balanced in terms of pointers for the range of goals), penal attitudes were expected to act as tiebreakers, whereas their role was expected to be irrelevant in the other vignettes. Results of the study show judges’ penal attitudes not to be relevant for preferred goals at sentencing in any of the four cases in the scenario study.

Thus, the current study went looking for a clear and consistent link between justifications and goals of punishment derived from moral legal theory on the one hand, and the practice of punishment on the other.

Such a link could not be established. The argument was put forward that if there is a consistent legitimising moral framework underlying the current practice of punishment, this should somehow be reflected by that practice. This argument has been explored from several points of view. The overall structure in general penal attitudes reveals a pragmatic inclination that is insufficient to serve as a consistent and legitimising (moral) framework. In specific criminal cases there was no agreement on the goals of punishment to be aimed for. Sentences in the same criminal cases differed widely and no substantial and consistent patterns of association between goals and sentences were found. Perhaps there are other mechanisms or processes, apart from those derived from moral legal perspectives that may provide sufficient justification and guidance for the practice of punishment. From the perspective adopted in this study, however, it seems safe to conclude that there is no consistent legitimising and guiding moral framework underlying the current practice of punishment.

While individualisation is valued in Dutch sentencing practice and judges may aim to individualise their sentences as much as possible, the scenario study has shown that individualisation can, depending on the sentencing judge, imply a wide variety of sentences in terms of type, severity, and special conditions for exactly the same criminal case. In the light of these findings, individualisation has, in fact, two components: a judgecomponent and a case characteristics-component.[ii] While individualisation in sentencing may be a highly valued principle in the Dutch practice of punishment, it obviously has a number of potential drawbacks. The wish to individualise sentences may, for example, be in direct conflict with the principle of equality in sentencing. Concerns about equality in sentencing have increased in the Netherlands over the last decade and have led to various initiatives to enhance consistency in sentencing. Initiatives for attaining a greater level of consistency in sentencing include structured deliberations between chairpersons of the criminal law divisions of the courts, attempts to formulate ‘band widths’ or ‘starting points’ for sentencing in certain types of cases, and the development of and experimentation with computer-supported decision systems and computerised databases (e.g., Oskamp, 1998). Without a commonly shared underlying moral framework or vision of punishment, the (strict) application of such essentially inanimate mechanisms may eventually lead to a bureaucratic equality in sentencing (cf. Kelk, 1992; Kelk & Silvis, 1992) in which the moral justification and goals of punishment are pushed still further into obscurity.[iii]

Moreover, and perhaps paradoxically, in the absence of a commonly shared vision on the justification and goals of punishment, it remains questionable whether or not such mechanisms will ever be accepted or consistently applied by sentencing judges (De Keijser, 1999). Perhaps cases similar to the harsh treatment vignette (i.e. few opportunities for rehabilitation/ reparation), where there was some level of consensus about the goals of punishment and appropriate type of sentence, will be the most amenable to the use of such mechanisms.

The present study constitutes an appreciable simplification of the complex and dynamic process of sentencing in real life court cases. By choosing such an approach, however, the extreme dependence of judges on external influences and mechanisms has been shown. A commonly shared vision underlying criminal justice on fundamental moral principles and their practical implications may constitute a first line of defence against extra-judicial influences, such as short-term criminal politics (e.g., passed on through the public prosecutor), and media hypes that may be considered undesirable. An intricate and at heart morally problematic institution such as legal punishment, that cannot fall back on and does not reflect a coherent underlying vision, will, in the long run, forfeit its credibility. On the part of policymakers, the necessity of normative and theoretical reflection already seems to become irrelevant or is even viewed as an obstacle (cf. ’t Hart, 1997). The essence of the practice of punishment is being reduced to or reformed into technocratic rationalisations primarily based on considerations for manageability, control (Van Swaaningen, 1999; Kelk, 1994; Feeley & Simon, 1992), and instrumentality (Foqué & ‘t Hart, 1990; Schuyt, 1985). One may legitimately wonder whether actions within such a practice can or should, in the long run, still be called ‘punishment’.

The fact that we have not been able to establish a clear and consistent link between justifications and goals of punishment derived from moral theories and the practice of sentencing, may be attributed to a number of causes. If one accepts the basic premise of this study, namely that punishment is morally problematic and therefore needs a consistent and practically relevant moral justification, the present results should at least lead one to reconsider and discuss the justification and goals of punishment and the way in which they relate to our contemporary practice. One argument may be that the theories of utilitarianism, retributivism, and restorative justice are in themselves plainly too awkward for practical purposes, i.e., to provide a clear and practically relevant legitimising and guiding framework for the contemporary practice of sentencing. Therefore, the gap between these legitimising theories of punishment and the actual practice cannot be bridged. Theoretical compromises, i.e. hybrid theories, will not effectively solve the problem. Hybrid theories, it has been argued, can very well disguise eclecticism in sentencing practice (cf. Chapter 2). A second argument takes the opposite point of view, i.e., that the practice of sentencing, conceived as an essentially morally problematic practice, is defective: it is a practice in which a coherent vision on the moral foundations of punishment and the goals at sentencing is absent. While individual judges may have their own idiosyncratic models of the relationship between goals of punishment and specific sanctions, such a relationship is hard to discern at the aggregate level. These arguments are not mutually exclusive. Moreover, either way, a defective link between moral theory and the practice of legal punishment, as observed in this study, remains. This suggests, at least, two general and simultaneous courses of action.

First, the necessity of serious and fundamental theoretical reflection is evident. In this respect, it is striking that in the Netherlands the theoretical debate appears to have died out. To date, relatively few lawyers and scholars appear to attach great value to moral theorising. An important course of action would therefore be to revive the theoretical debate, not just for the sake of theorising, but rather for the sake of repairing the moral foundations of legal punishment with clear implications for sentencing practice.

A second and related course of action would be to put serious effort into reaching a consensus and to make the link between (theoretically derived) goals of punishment and actual sentences explicit. Such deliberations should not simply include principal punishments, but the whole array of sentencing options that are currently available to judges. This requires serious reflection and, more importantly, would imply making certain commitments that may not be popular from a political perspective. While mixing cocktails consisting of a multitude of frequently conflicting goals may be smart from a (short-term) political point of view, it renders sentencing practice impalpable and difficult to legitimise. Rather than conceiving of such processes as attempts to limit judges’ discretion in sentencing, they may eventually help to avoid more serious constraints on sentencing discretion through bureaucratic mechanisms. Currently, in the Netherlands, the unduly complex and fragmented nature of our sanctions system is being scrutinized. The Department of Justice has recently suggested a number of ways to streamline the system (cf. Department of Justice, 2000; see also Justitiële Verkenningen, 2000). Incorporating explicit and well-considered notions of the link between punishment and purpose in such a process of streamlining is an opportunity for real improvement that should not be missed (cf. Van Kalmthout, 2000; see also De Jong, 2000).

These courses of action should constitute the first steps towards a sentencing practice that is less impalpable and more coherent. Simultaneously they may stimulate a search for other methods of promoting disciplined conduct and social control (cf. Garland, 1990). As such, they may fuel a process of decremental change (Braithwaite & Pettit, 1990) in the reach and workings of the current criminal justice system. Obviously the debates should not be limited to the judiciary but must also be extended to the legislator and the government.[iv] One of the great challenges is to establish common ground for such debates. After all, political and philosophical reflection can often be difficult to reconcile (’t Hart & Foqué, 1997). The readiness of criminal justice officials, government, and the legislature to address these issues will depend on an acknowledgement that the current state of affairs is unsatisfactory. It will also depend on the belief in the potential to improve the current state of affairs and, subsequently, on the actual willingness to act on these beliefs (cf. Likert & Lippitt, 1966; see also Denkers, 1975). This study may contribute to the acknowledgement of this fundamental moral problem in contemporary criminal justice.

Powerful tools that can contribute to the process of improving the current state of affairs are readily at hand. Structured deliberations between chairpersons of the criminal law divisions of the courts, a council for the administration of justice, attempts to establish ‘band widths’ or ‘starting points’ for sentencing in certain types of cases, and the development of and experimentation with computer-supported decision systems and computerised databases have been focussed on attaining greater levels of consistency in sentencing. Consistency in sentencing does not necessarily solve the moral problems at stake. Moreover, without a commonly shared vision of the justification and goals of punishment and the way they should relate to actual sentences, the effectiveness of such initiatives is questionable. However, these initiatives are the tools par excellence for making differences explicit (in terms of goals and motivations as well as in terms of sentences) and for forming a body of knowledge on which a common vision can start to take shape.

NOTES

i. For further objections, see Doorenbos (1999) and Corstens (1999).

ii. Recently, after an examination of sentencing disparity in the British House of Lords, Robertson (1998) also stressed the highly personal nature of judicial decision-making. By identifying which judges tried the case, he has been able to correctly predict the outcome of appeal cases more than 90 percent of the time. His study, however, focused on differences between judges on other types of dimensions than the penal attitudes employed in this study.

iii. For instance, the formulation of ‘band widths’ or ‘starting points’ in sentencing for certain types of cases is predominantly founded upon averages of sentences passed in similar cases.

iv. Concerning the specific maxima (i.e. per individual offence) of principal punishments in Dutch criminal law, such a fundamental reflection on part of the legislator was recently recommended by De Hullu et al. Normative standards that (ought to) underpin legislative choices and decisions need to be developed and made explicit (De Hullu, Koopmans, & De Roos, 1999).