At Western Sahara: Visiting A Forgotten People

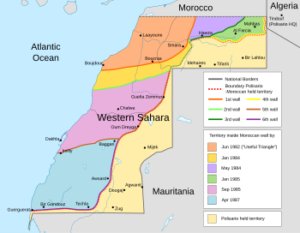

Western Sahara – Map: en.wikipedia.org

06-17-2024 ~ South of the Algerian town of Tindouf on the border with Western Sahara are five refugee camps. The camps are home to the Sahrawi people of Western Sahara and are administered by their freedom movement Polisario, which is fighting to liberate their homeland from Morocco.

Life in the desert camps leaves a deep impression and testifies to a people who, despite limitations, have managed to build a well-organized society under harsh conditions. “We Sahrawis were originally a nomadic people who used to travel around on camels and settled in different places in and around Western Sahara. There were no borders that limited us from moving into what is today Mauritania or Algeria,” said Jadiya who is a translator.

The colonial era saw European powers come to Africa to take over territories, exploit labor, and extract natural resources. In Western Sahara, the Portuguese and French were first beaten back by the local population before Spain managed to colonize the area in 1884. In 1973, the Polisario freedom movement was established by the indigenous Sahrawi people to liberate their land from the Spanish empire.

Western Sahara remained a Spanish colony until 1975 when the Moroccan government organized a so-called “Green March” with 350,000 protesters marching into Western Sahara to claim the land. The protesters pressured Spain to leave Western Sahara, which Morocco then occupied. Today, Western Sahara is still occupied by Morocco and is thus considered to be Africa’s last colony.

Desert Camps

It is around 35 to 40 degrees Celsius in Wilayah of Bojador, the smallest of the five refugee camps on the border with Western Sahara. My feet are boiling in my shoes, but walking in bare feet is not an option. The sand is far too hot. According to Filipe, a local Sahrawi engineer educated in the Soviet Union, it has been five to six years since it last rained in the camps. “Not a single drop from the sky,” he says.

In the refugee camps, people live either in simple huts with tin roofs or in “getouns,” square tents with entrances on all sides and a large colored carpet as a floor. Skeletons of cars stripped of wheels, doors, windows, seats, and all interior parts remind me of apocalyptic TV shows. Car doors are reused as fencing for the village’s many goats, which are often seen wandering around in herds on the sand hills in the camp. However, the many car frames work well as playgrounds for children who would otherwise not have access to slides, swings, or climbing frames.

The Wall of Shame

Western Sahara is divided into three areas. There is the region of Western Sahara where the occupying power Morocco is in power. There are the liberated areas of Western Sahara, where the freedom movement Polisario is in power. And then there are the refugee camps in Algeria, where Polisario is also in power. To separate the different areas from each other and maintain control over the occupation, the Moroccan monarchy built a 2700-kilometer wall across Western Sahara.

“The Wall of Shame,” as the Sahrawis call it, can easily be compared to Israel’s apartheid wall in Palestine, as both were built by occupying powers and effectively force indigenous families and other communities to live apart from each other.

Although the Wall of Shame is built of sand, “it’s the most dangerous wall in the world,” a Polisario soldier says. The wall is divided into several lines: barbed wire, dogs, a moat, the wall itself, 150,000 soldiers, and eight million landmines. The outermost line is the numerous mines. In addition to making it harder for Polisario soldiers to penetrate, civilian nomads or local cattle are often blown up from stepping on the mines.

A Temporary Situation

As a result of the Moroccan occupation, thousands of Sahrawis fled in the 1970s to the refugee camps in Algeria, whose government allowed Polisario to administer the camps as part of the liberated territories.

The five refugee camps in Algeria are named after towns in Western Sahara. For example, Wilayah of Bojador is named after the city of Bojador, which is in one of the areas ruled by Morocco. “Each camp is named after one of our cities to signal that the camps are temporary. It’s to show that we will return to our real cities one day,” says engineer Filipe.

Wilayah of Bojador may be the newest and smallest of the five refugee camps administered by Polisario. But when I stand on the camp’s largest hilltop, I can see houses and tents far out on the horizon. All around the camps is the flag of Western Sahara, which with its black, white, green, and red colors is very similar to the Palestinian flag. The only difference is that the Western Sahara flag has a red crescent and star in the middle. “The black color symbolizes the occupation. Today, the black color is at the top, but when we will achieve our freedom, from that day on, we will fly the black color at the bottom,” says Filipe.

A Well-Organized Society

Despite limited access to resources, the Sahrawis have in many ways managed to build a well-organized society. For example, each camp—which is considered a region—is divided into several small districts. Each district has a small health clinic, and each camp has a regional hospital. In addition, there is an administrative camp where the main hospital is located. “If you are ill, you first visit the health clinic in your district. If they cannot help you, go to the regional hospital. If they cannot help you either, you go to the administrative camp hospital, then to the hospital in the nearby Algerian town of Tindouf, then to the Algerian capital Algiers, and finally to Spain,” says Filipe. “It is very well organized.”

Around the Wilayah of Bojador, there are small shops where you can buy groceries like rice, pasta, potatoes, and canned tuna. In the camp, I encounter everything from a school, kindergarten, women’s association, and a library to a hairdresser, a mechanic, and small stalls selling tobacco or perfume.

A truck travels the narrow, bumpy roads from home to home, filling bags—the size of inflatable trampolines—with water so families can drink, bathe, and wash their clothes. According to the NGO, The Norwegian Support Committee For Western Sahara, international observers describe the Sahrawi refugee camps as “the best-organized refugee camps in the world.”

A Life Outside the Camp

The Sahrawis and Polisario are doing the best they can to create a dignified life for the people in the refugee camps. But it is not free of challenges. According to Fatima, a member of the Sahrawi Youth Union, one of the biggest challenges today is that there is an older generation that can remember a life before the camps, while a large younger generation has lived their entire lives in the camps.

“To prevent children in the camps from growing up without knowing about life outside the camps, we have set up a scheme where children are sent to Spain to live with a family for a period of time. In this way, they become ambassadors for Western Sahara in Spain, and they see that there is life outside the camps,” says Fatima. When Fatima was six years old, she was part of the program. “I had never in my life seen a fish or seen so many green trees in the same place. I thought it was just something you saw in movies. That it wasn’t real. But in Spain, I learned that it’s real,” she recalls.

Challenges

There are still problems that Polisario and the local population in the camps struggle to solve. Several young men say that job opportunities vary and that they are often unemployed. Even the men and women employed in hospitals and police stations only receive a salary once every three months, and the pay is not high. Many young unemployed Sahrawis must go abroad to find a job. In the meantime, they volunteer in the camps to carry out various practical tasks.

Refugee camps rely on international donations from bodies like the UN or from other countries. When a bus in Spain is damaged and no longer meets national safety requirements, it can be sent to Western Sahara. Here the buses, which are very similar to Danish city buses, drive around in the sand with passengers. But in many ways, the Sahrawis live a limited life in the camps at Tindouf. During my entire stay, I didn’t see a single trash can. The lack of a waste system means that cigarette packs, plastic bottles, and other rubbish are strewn around the camp.

The power goes out frequently and connecting to the internet is generally a problem. The latter is considered a major problem for the Sahrawis, who want to connect with people in the wider world to bring international attention to their resistance struggle.

Promoting the Cause

The Sahrawis are interested in drawing attention to their cause. In the desert, they have established a museum called the Museum of Resistance, where tourists are taken on a journey from the Sahrawi’s original nomadic life through the colonial period and the Moroccan occupation to Polisario’s fight for liberation. The museum includes a miniature version of the Wall of Shame and several of the tanks and weapons that Polisario soldiers have managed to take from the Moroccan military. In the desert you will also find a media house where journalists sit behind desktop computers, writing articles and updating the Polisario website and social media with news from the camps. There are soundproof rooms, microphones, and soundboards to record radio broadcasts, and studios with green screens and video cameras to record TV news. Polisario has its own TV channel.

In addition, the Sahrawis organize the renowned international film festival FiSahara, which brings people from all over the world. Many of the international guests at the film festival come from Spain. Sahrawi President Brahim Ghali met journalists at the festival. He criticized Spain’s prime minister Pedro Sánchez for changing his country’s position regarding Morocco’s occupation; in 2022, Sánchez wrote to Morocco’s King Mohammed VI to say that he agreed with the view that Western Sahara should be autonomous but under Moroccan rule. “We have frozen our relations with the Spanish government, but we still have good relations with the Spanish people,” said Sahrawi President Ghali.

By Marc B. Sanganee

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter. Marc B. Sanganee is editor-in-chief of Arbejderen, an online newspaper in Denmark.

Source: Globetrotter

06-09-2024. Europeans go to polls this week for parliament vote. What is at stake? Is the future of the European Union (EU) at risk on account of the surge of the far-right? But is the EU even a democratic institution worth saving? And why is the Left in crisis across Europe? Political economist/political scientist C. J. Polychroniou tackles these questions in an interview with the French-Greek independent journalist Alexandra Boutri.

06-09-2024. Europeans go to polls this week for parliament vote. What is at stake? Is the future of the European Union (EU) at risk on account of the surge of the far-right? But is the EU even a democratic institution worth saving? And why is the Left in crisis across Europe? Political economist/political scientist C. J. Polychroniou tackles these questions in an interview with the French-Greek independent journalist Alexandra Boutri.