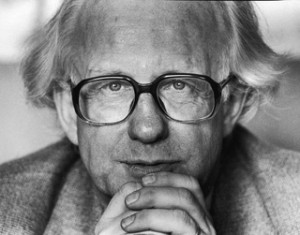

Johan Galtung

12-09-2024 ~ Based on his experience as a mediator in many conflict areas, the author discusses twelve approaches to reconciliation.

He concludes that no single approach is capable of handling the complexity of the situation after violent events, thus combining approaches makes more sense.

The parties involved in the conflict should be invited to discuss these approaches and therefore be able to arrive at the best combination for their own situation.

Key words: conflict theory, peace work, reconciliation

Reconciliation is a processed aimed at putting an end to conflict between two parties. It includes a closure of hostile acts, a process of healing and rehabilitation of both perpetrators and victims. Reconciliation processes often require the intervention of a third party. That party attempts to manage the relationship between perpetrators and victims (Galtung, 1998).

During the reconciliation process the victim can seek restitution for the harm from the perpetrator by having the perpetrator punishedor give compensation. Another possibility is that the victim ‘gets even’ with the perpetrator through revenge. This may bring some gratification, but it may not automatically bring healing from trauma.

The perpetrator may seek release from his guilt through submission, penitence or apology and asking forgiveness.

Since reconciliation essentially takes place between perpetrator and victim, either of them can block the process. In that case, the trauma and guilt live on, and eventually may fuel new conflicts.

In this article twelve different approaches to reconciliation will be discussed.

1. The ‘blaming the circumstances’ approach

During the process the third party tries to change the perspective of both perpetrators and victims on the cause of their conflict. Cultural factors and/or structural deficits in society are identified as the real underlying causes of conflict. Reconciliation is possible as soon as both parties agree on these causes. The key word here is ‘agree’. ‘Outer conditions made you a perpetrator and me a victim. That is not a good reason for us to hate each other, for you to feel excessive guilt, or for me to develop a victim psychology. We can close the vicious circle and heal our psychological wounds. We can even reconcile with each other and put the past behind us. We can join forces and fight those conditions that pitted us against each other in horrible acts of violence.’

Even if this is not the full truth, it can be more than half the truth. Moreover, it can be self-fulfilling.

Outsiders, like peace workers, may suggest that perspective as a way of thinking about their own situation. This may best be suggested to one party at the time rather than the parties together. This avoids the victim getting upset by seeing the perpetrator grab the opportunity ‘to cash in’ more on his professed guilt. It is important they first arrive at an exculpatory position, and then bring them together to celebrate a joint approach.

The peace worker’s task is to carefully and tactfully open the eyes of all parties on the potential peaceful aspects.

2. The reparation/restitution approach

X has harmed Y. X is conscious of his guilt; Y is conscious of the trauma. X comes to Y and offers reparation or restitution: ‘I’ll undo the harm done by undoing the damage’. At the simplest level, for example a tenant buying a new vase to replace a broken one, to the most complex level of countries and alliances at war with each other; money, goods and services are used to undo damage. Sometimes the relation is direct, sometimes via institutions like insurance companies (e.g., for damage done to cars in accidents; countries are not yet insuring against damage in wars). However, as any house- or car-owner knows: there is also the inconvenience and time lost in the process. Reparation must always be at a higher level than simple replacement cost. This approach will only work when the harm done is reversible.

When trauma has been caused and is deeprooted, any restitution borders on an insult to the victim. There is an element of ‘buying oneself off the hook’ by attempting to make the victim forget what happened. The harm is reduced to a commodity to be traded: ‘By mistake I took something from you, here, have it back with an extra 10% for inconvenience and time lost’.

The task of the peace worker is to explore all possible arguments with the perpetrator and the victim so that they fully understand what is involved if this is the approach chosen.

They both have to accept the approach, so that the perpetrator does not offer something that falls on barren soil, or worse – increases the aggression. Moreover, the victim should not be further harmed by expecting a restitution that never comes, for whatever reason.

Another task that may fall to the peace worker is that of suggesting what might constitute a concrete act of restitution. People might have limited idea of what would be suitable, and this aspect must be taken more seriously than finding a gift for an anniversary. In addition to being wanted by the victim, the act of restitution must convey the correct symbolic message. That is also relevant for the perpetrator. He may for instance, be afraid that the act of restitution is an implicit admission of guilt and can be held against him as a confession. He may also worry lest the act does not lead to closure as a condition for reconciliation. He may wonder about the time perspective: are we talking about one act, or about a repetition, such as every year, like the anniversary of the violent act?

Restitution is a transaction, a two-way action that must contain balance and symmetry. The instrument to ensure that is a contract, signed by both perpetrator and victim. The peace worker should know how to draw up a document of this type; in short, s/he has to be a bare-foot lawyer, in addition to a theologian and a psychologist for reconciliation tasks. There may be objections that a contract is too formal, not sufficiently spontaneous, symbolic, or healing. However true, for those who choose this approach, that may be a minor matter.

3. The apology/forgiveness approach

X has harmed Y; X is conscious of his guilt, Y is conscious of the harm. Both are traumatized. X comes to Y, offers ‘sincere apologies’ for the harm, Y accepts the apologies.

Metaphors of turning a page, opening a new chapter, even a new book, in their relations are invoked. The slate is wiped clean, and will now be inscribed with positive acts. There is agreement that what happened is ‘forgotten’ and not to be referred to again.

However, is it also ‘forgiven’? Does ‘I accept your apology’ mean ‘I forgive you’? This is definitely not true and may have a variety of meanings. Some possible translations

– ‘I apologize’=‘I wish what I did to be undone and promise, no more’

– ‘I accept your apology’=‘I believe what you say, let’s go on’

– ‘Please forgive me’=‘Please release me from my guilt to you’

– ‘I forgive you’=‘I hereby release you from your guilt to me’

Thus, forgiving goes one-step further in relating to the trauma of guilt. Guilt is in the spirit, and arises from the consciousness of having wronged someone. This establishes a relation to the victim, to one’s own ego, and to any God/State believed in. The victim can only release the wrongdoer from the first form of guilt. To some, that is the only guilt acknowledged or perceived.

A positive effect of this approach is a bond of compassion between X and Y. A negative effect is its superficiality. Just as restitution is good for people with money, apology is for those good with words. X agrees to see the harm as wrong, as something he wishes undone, and Y helps him by saying that you can now live as if no harm was done. Yet, the root causes of the violence remain and are untouched.

For the peace worker this is very different from the reparation/restitution approach. There is a transaction which requires both parties to be willing, meaning that either one can sabotage the process. This can occur if the victim does not accept the apology, or does not to forgive; or if the perpetrator does not to extend an apology, or not ask for forgiveness.

In addition, whereas there is something economic and contractual in the process of restitution, this transaction is spiritual/psychological. Both parties have to be ‘in the mood’ to enter this relationship. This is frequently preceded by a feeling of ‘having looked into the abyss’; it is this, or hatred, retribution rather than restitution, with no end of the violent cycle.

The peace worker has to have it all in his/her mind and hands, actively steering the process toward closure. It requires knowledge, skills and above all human tact, with the only training mostly on the job.

4. The theological/penitence approach

This approach consists of a well-described, well-prescribed chain: submission-confession-penitence-absolution; to and from God. The penitence is mainly self-administered: prayer, fasting, celibacy, joining a monastery, and flagellation. The belief is some pain in this life is better than eternal pain in the after-life. Absolution thus releases the perpetrator as the sinner from his guilt unto God.

One problem is that this only works for the believer, or for the person who at least has some belief. There is little in this approach for the atheist.

A religious leader, in this case, holds the role of peace worker. What should he be encouraged to be a good peace worker on top of his theological role? The basic point has already been mentioned: to broaden the perspective. The priest helps by paving the way for reconciliation with God, and thereby for the believer, with the self. To do this he may have to strengthen the faith in self and help remove doubts. However, the other, the victim, still remains and is the forgotten party in this transaction.

In looking at the approaches already discussed, broadening the perspective means taking something away from one, or more of them. Obviously, the priest cannot make full use of the previously mentioned ‘blaming the circumstances’ approach, because he stresses the individual responsibility of the sinner. Yet, he can make use of the reparation/restitution approach and the apology/forgiveness approach.

What is recommended is that the priest, as peace worker, must include the victim. In some cases, the victim might say: ‘Leave me alone, I have had enough suffering. I do not want to add more by having to meet him again, accept some act of restitution, or even listen to his insincere apologies. None of that will ever undo what has happened.’ This reaction is understandable, and the peace worker may have to be a go-between if the direct encounter is judged to be too hard on either, or both. Rather than bringing them together, he may have to rely on an individual dialogue with each of them.

5. The juridical/punishment approach

This is the secular version of the above The successor to God is the State. The judge takes the role of the priest. The prescribed process above now reads submission-confession-punishment by seclusion-readmission to society. The logic is the same. The perpetrator is released from the guilt toward ‘society’; the other two forms of guilt remain. For problems, see above. 2)

How do International Tribunals work in terms of collective violence? Much as one would expect: the accused tend to be the perpetrators of person-to-person violence, those who kill with machetes and gas cham- bers, not those who kill with missiles and atom bombs; and they would tend to be the executors of violence rather than the civil- ians giving the order, or setting the stage. As a result, the general moral impact will probably be relatively negligible.

Yet tribunals exist, with a major one for war crimes, crimes against humanity and geno- cide being created. As conceived of within the juridical/punishment framework, they will all have more or less, many of the problems discussed above. The key to the solution is broadening the approach by adding other solutions as well.

The name of the peace worker, in this case, is the judge (and, to a much lesser extent, some of the prison personnel).

Like the priest the judge is also used to adding additional aspects to his juridical profession, which, like the priest, implies that what happens is according to the Book.

What should he look for to be a good peace worker on top of his juridical role? He should realize that the task is not finished when the relation to the International Community (of States) has ended because the prison sentence has been served. The perpetrator-state perspective is too narrow. Imprisonment does something to the body by limiting physical movement; yet leave the capacities of the spirit basically untouched, and in some cases, enhanced. The judge should add the skills of the priest, and the priest may have to learn how to do the theological/penitence approach with non-believers. Then there is also the possibility of adding the restitution and apology approaches. This could even be included as part of the sentence with a tacit or explicit understanding that the success of the process could shorten the sentence, but not include amnesty. The truth has pre- sumably already come out through the well-tested methods of the juridical approach, with evidence, testimonies, pleas (pro et contra), and final evaluation.

6. The co-dependent origination/karma approach

In Buddhism it is believed that although any human being at any point can choose not to act violently, the decision is influenced by his karma, his moral status at that moment. This karma is the result of the accumulation of ‘whatever you do, sooner or later, comes back to you’. But the victim’s karma, and their joint, collective karma also contributes to this decision. All karma flows from the merits and demerits of earlier action.

Since these intertwining chains stretch into the past-lives, the side-lives of the context and the after-lives of the future, the demerit of a violent act cannot be placed at the feet of a single actor only. There is always shared responsibility for bad karma. Hence, the way to improve karma is through an outer dialogue, which in practice means a round-table where the seating pattern is symmetric, allocating no such roles as: defendant, prosecutor, counsel, or judge, and with a rotating chairperson.

Preparation for these round-table dialogues should include meditation as an internal dialogue, with participants trying to come to grips with the forces inside themselves. Thus, in Buddhist thinking, there is no actor who carries 100% of the responsibility alone; it is all shared. Whereas Christianity can be accused of being too black and white, Buddhism can be accused of being too grey. However, the idea of cooperating to plug the holes in the boat we share, rather than searching for the one who drilled the first hole, and having a court case on board as the boat is sinking, is appealing, both for conflict resolution and for reconciliation.

In conflict theory, the concept that comes closest to this is the conflict formation. The first task in any conflict transformation process is to map the conflict formation, identifying the parties that have a stake in the outcome, their goals, and issues, as well as defining any conflict of goals.

The peace worker can use the mapping tool of the conflict worker, and proceed in basically the same way. He can have dialogues with all parties over the theme ‘after violence, what’? He can identify conflicts, hard and soft, and try to transcend them by stimulating joint creativity. Or, he can bring them all together and be the catalyst and facilitator around, rather than at the head, of the round table. Conflict work and peace work are closely related, and this approach is based on the combination of inner dialogues (meditation) and outer dialogues, with or without the peace worker as a medium.

The karma approach is an excellent point of departure, given its holism, neutrality and appeal to dialogue. In that sense it is actually a meta-approach, above or after the other approaches, accommodating all of them, like the ho’o ponopono approach outlined at the end. It is an attitude, a philosophy of life, beyond the stark dichotomy of perpetrator-victim, and in that sense different from the preceding five, and similar to those approaches that follow.

7. The historical/truth commission approach

In this approach the basic point is to describe, in great detail, what actually happened. In trying to explain it, letting the acts, including the violent ones, appear as the logical consequences of the antecedents. The assumption is that deeper understanding may lead to forgiving. Although ‘getting the facts straight’- however ugly – is important, there are serious problems with this approach.

To begin with, mere understanding does not always result in forgiveness. The hideous acts stand out, whether they include the names of perpetrators or not. Also, if they are not pardoned, why should they receive impunity, or get off the hook? It may be argued that the perpetrators will also read the report that establishes their guilt to the victims, to themselves and to the God they may believe in, and will be tormented by that and by social ostracism. That is punishing, not forgiving.

Next, this does not by itself produce the catharsis of an offered and received apology, nor the hoped for and offered forgiveness. Truth alone is merely descriptive, not spiritual.

Furthermore, this approach does not deal with the question ‘how do we avoid this in the future?

Lastly, it limits the process to professionals whose task is to come up with the official version. It may be far better have 10 000 people’s commissions, in each local community and each NGO, using round-tables which involve all parties whereby they themselves try to arrive at a joint understanding and reconcile in the process.

The task of the peace worker is to organize these dialogues and to ensure that the findings flow into some general pool. One way to accomplish this is to put at the disposal ofthe citizens in any part of a war-torn society, village, ward, company, or organization, a large book with blank pages to be inscribed. The book will become a part of the collective memory, no doubt subjectively formulated, but that also has its strengths. Rather that than the truth lawyers and historians who think they can establish a single book that will encompass thousands of truths.

Contained in the book would be descriptions of violence and traumas, not only what happened but also how it touched them and wounded them. Added to that would be their thoughts on what could have been done, on reconstruction and reconciliation, the resolution of the underlying conflict, and their hopes for the future. In other words, the citizens would establish their own truths for themselves.

Something like this was done by the Opsahl Commission for Northern Ireland some years ago, and no doubt played a role in externalizing the conflict by seeing it as something to be handled objectively, outside the participants.

Soka Gakkai in Japan has also done an impressive job collecting the war memories of many women in 26 volumes, thereby establishing a collective memorial to be consulted by future generations. However, the major task of the peace worker is to give the search for truth the two twists indicated while remaining truthful to empirical facts: counter-factual history, what might have happened if, and the history of the future, how do we avoid this in the future. Again, let 10 000 dialogues bloom.

8 The theatrical/reliving approach

This approach would use exactly that: involving all parties, in numerous exercises to relive what happened. This is not about documentation and ‘objectivity’, but of reliving the subjective experience. The ways to do this are numerous; telling what happened as it happened, as a witness to a historical/truth commission is already reliving, revealing and relieving. To have the other parties do the same, adds to the whole.

To tell the stories together, in the same room, adds a dimension of dialogue, which can easily become very emotional (that’s not how it happened! is that why you did it?) Then, to stand up, re-enact it up to, but not including, the violence, may have a cathartic effect provided there is an accompanying tension release through dialogue. The parties may even switch roles, which some might see as coming too close. However, it depends on the parties involved, like in a negotiation sometimes it is better to keep the parties separate. The important point is to arrive at a deeper understanding, which is more emotional and less descriptive.

An alternative approach is, of course, for a professional to write this up and present it on national television for common con- sumption. In general, this should not be excluded, but should occur in plural, not with the idea of writing one play to finish all plays.

A basic advantage of the theatre approach, however rudimentary and amateurish, is that it opens windows so often closed to positive social science: what might have happened if and how do we avoid this in the future? The actors can relive history up to the point where it went wrong and then, together, invent an alternative continued scenario, up to inventing alternative futures, with theatre as future workshops. A play can be rerun at any point; history, unfortunately cannot.

The peace worker would have to talk with all parties in advance, have them tell their truths about what happened and then get their general consent for the theatrical approach. It should be done with the real parties as actors, and very close to the real story. For example, in a sexual harassment conflict in a school with a student complaining that the teacher made advances and the teacher denying that this was the case. In this case, the principal may say, show us what happened. In such a real case those who watched concluded that the teacher did not ‘go too far’, but also that the girl had good reasons for having apprehensions about what might have happened next. In a concrete situation there are so many dimensions to what happens that words are hardly able to catch it all. Enacting may help explore those dimensions.

Others may be called on as stand-ins for roles or scenes too painful for the real par- ticipants to enact. The drama can also be rewritten so that ‘any similarity with any real case is totally coincidental’. The point is to give vent to emotions in a holistic setting by enacting them, taking in as much of the totality of the situation as possible. Writing the play, before and/or after it was enacted, can also prove very valuable.

Technically, videotaping may be useful, not only to improve the accuracy of the enactment (‘let us take that one again, I am not sure you captured what happened’), but also to be able to stop the video and say: ‘this is the turning point. This is where it went wrong. Let us now try to enact an alternative follow-up, what should, and what could, have been done’. Obviously, making and enacting conflict-related theatre is an indispensable part of the training of conflict workers for reconstruction and resolution, not only for reconciliation.

9.The joint sorrow/healing approach

This approach is carried out in the following way: joint sorrow is announced for all conflicting parties. The myth that some people ‘gave’ their lives during the armed conflict is explored for what it is: those people had their lives taken away from them by incompetent politicians who were incapable of transforming conflict, themselves incurring little or no risk but willing to send others into (almost) certain death, and spreading that death to others in the process. Without opening a new front against the political and military class as a common enemy, war as such is deeply deplored. People dress in black, sit down in groups of 10-20 including people formerly enemies. They examine the basics: how could the armed conflict have been avoided? How can it be avoided in the future? Are there also acts of peace that can be highlighted and celebrated?

To discuss how an armed conflict could have been avoided is not new; any country that has been attacked may engage in that debate on each anniversary (one conclusion is often to keep the powder dry, and be better armed next time). To discuss this together with the aggressor who jointly deplore war, any war, as a scandal and a crime against humanity, searching for alternatives both in the past and the future, is a relatively new and promising approach.

The main issue at point is the togetherness. As time passes, more meetings in take place, including gatherings of veterans on both sides. The other side of the military story; evaluating victories and defeats in the light of new information gained may fascinate them. If they are soldiers in the real sense, then there may be no need for any reconciliation. They were professionals doing a job, unfortunately destructive rather than constructive. All professionals, even soldiers, want to know whether they did a good job; few would know this better than the other side.

The task of the peace worker is not to organize encounters of demolition experts however, but to have veterans meet civilians, civilians meet civilians, and to have both of them meet the politicians who gave the orders. The question to be asked is: when will any acts of war, and not only cruelty on the ground, come with the names of those responsible on them? Who ordered that bombing, killing X civilians? Not only the well-known names at the very top of the hierarchy, their orders are usually general, but the generals whose orders are specific. Such encounters should not become tribunals. The focus is on healing through joint sorrow, not on self-righteousness. The model could be a village, town, or district recently hit by natural disaster. There are local fault-lines and enmities; although no one would accuse any one on the other side of a fault-line of having caused or willed, a disaster. Yet, there are casualties and massive bereavement with visible signs of shared, joint sorrow across fault-lines, such as flags on half-mast and people in black.

Of course there is also healing in this. Right after a war may be too early for joint sorrow. Nonetheless, after some years the time will come and that opportunity should not be lost.

10. The joint reconstruction approach

Once again, the point is to do it together. German soldiers used a scorched earth tactic in Northern Norway, leaving nothing to the advancing Red Army and driving out the inhabitants. Would it be possible for those inhabitants to cooperate with the soldiers after the war is over, making the scorched earth bloom again, coming alive with plants, animals, and humans, with building and infrastructure?

A good thing would be to have civilians from the same nation come and participate in the reconstruction. Of course, they should not be representatives of the perpetrators of the violence, and may even be their antagonists (like sending conscientious objectors to clean up after the soldiers, the non-objectors).

However, they would demonstrate that there are both hard and soft aspects of that nation, as of any nation, that could count toward depolarization. Moreover, there would be no direct confrontation between perpetrators and victims; years may be required before that could safely occur.

Nevertheless that should remain the eventual goal. Which brings us back to the point about revenge: by violence going both ways not only harm but also guilt may be equal- ized (to some extent); the parties meet as moral equals. Yet, it would be far better to build moral equality around positive, constructive acts rather than negative ones.

Hence, the argument would be for soldiers on both sides to disarm and then meet, but this time to construct, not to destruct. Then victims could meet with victims, command- ing officers (COs) with COs, etc. This could serve as preparations for perpetrator and victim meeting, both of them together trying to turn their tragedy into something meaningful through acts of cooperation, rather than inserting some third parties in- between.

Once, when the present author was suggesting this approach in Beirut there was an interesting objection: this will not work here. In Lebanon there were not two parties fighting each other, but seventeen. Ammunition was used like popcorn, peppering houses, very rarely hitting the openings, yet still leaving bullet-scars all over. The response could be: no problem, get one former fighter from each group, give them a course in masonry, put seventeen ladders parallel, have them climb to the top and repair the facades as they descend.

Use the high numbers as an advantage. What a TV opportunity – provided there is also a spiritual side to the joint work.

That last point contains the crux of the matter. While rebuilding is a concrete, practical act, reconciliation is mainly spiritual. What matters is the togetherness at work; reflect- ing on the mad destruction, shoulder-to-shoulder and mind-to-mind. The preceding four approaches could give rich texture to the exercise: joint sorrow would seep in even if rebuilding could also be fun. Reflection on futility would enter. For this to happen, those who did the destruction should also do the construction, facilitating reliving on the spot. In doing so, two or more parties will find together a deeper, more dynamic, truth. Also, they will realize how deeply they share the same karma or fate.

In this, the peace worker should remember that there is much more to reconstruction than simply rebuilding physical infrastructure. Institutions have to function again; there are heavily war-struck segments to care for, refugees and displaced persons to resettle. There is much to be overcome by reconstructing structures and cultures. War hits all parties in some way; some lightly and some more heavily. It is inconceivable that no one from the former enemies will cooperate in joint reconstruction.

11. The joint conflict resolution approach

If joint reconstruction might be possible, how about joint conflict resolution? After all, that is what diplomats, politicians, and some military to some extent attempt to do. Nonetheless, there are two basic problems with this approach regardless of the quality of the outcome. It is top-heavy, anti-participatory and therefore in itself some kind of structural violence, often excluding the very people on whose behalf they presumably are negotiating behind veils of secrecy. Often they are protected elite who may not themselves have been the physical or direct victims of violence and may even be responsible for unleashing that violence.

So the argument here would be for general, even massive, participation. Two ways of doing this have already been given: the therapy of the past, having people discuss what went wrong at what point and then what could have been done; and the therapy of the future, having people discuss and imagine how the future would be if there is work done in favour of a more sustainable peace, and what that work would look like, starting here and now. In short, having people as active participants in conflict resolution; as subjects, not only as the objects of someone else’s decisions or deeds

It is in this process that human and cultural healing, as well as structural healing, would take place. As previously mentioned, a major form of horizontal structural violence before, during and after a war is polarization; what could be more depolarizing than reconciliation through joint efforts to solve the problems?

The psychological costs might be considerable; but the social gains would be enormous. What would be required would be for the ideas to flow together in a public joint idea pool.

Here the peace worker becomes a conflict worker again, trying Conflict Transformation By Peaceful Means. For example, efforts were made in the ‘before violence’ phase; is it now easier or more dif- ficult in the ‘after violence’ phase? No doubt it is more difficult in the sense that there is more conflict-related work to do: reconstruction and reconciliation. But is the resolution, or transformation, also more difficult?

This can argued both ways. On the one hand, the violence may have hardened both sides. The victor, if there is one, feels he can dictate the outcome, having won the violent process.

The loser thinks of revenge, and may never accept the outcome in his heart. Yet, there may also be acceptance, even sustainability, if the terms are not too harsh. Also, there may be a fatigue effect; whatever the outcome, never the violence again! How long the fatigue effect lasts is another matter.

One problem, mentioned above, is that the tasks of reconstruction are so pressing that reconciliation, let alone resolution, often recedes into the background. The peace worker has to keep the resolution discussion alive. Above we have given many examples of how reconstruction and reconciliation can transform the whole society so that a conflict that once was very hard can be softened. In this way, Germany will probably ultimately have no border problems, because the borders wither away within the super-national organization, the European Union. It is an overarching structure that has reduced the polarization in Europe’s midst, and made transformations possible in the long run.

12. The ho’o ponopono approach

A man is sleeping in his home when he hears some noises, he gets up, catches a young boy on his way out, stealing money. The police are called, and the young boy is now a ‘juvenile’ known to the police, obviously a ‘delinquent’, and as they say: ‘three strikes and you are out’. The place is Hawaii. In Hawaiian culture there is a tradition in a sense that combines reconstruction, reconciliation, and resolution, the ho’o ponopono (setting straight). This concept may be known through cultural diffusion, e.g., to the owner of the burglarized, violated house. He looks at the boy and thinks of him serving twenty years in prison, and he looks at the police. ‘Hey, let me handle this one’. It transpires that the boy’s sister is ill and the family is too poor to pay for medication. Every little dollar counts.

Ho’o ponopono is organized. The man’s family, neighbours, the young boy and his family, all sit around the table; there is a moderator who is not a member of the families or neighbours, the ‘wise man’. Each one is encouraged sincerely to present his/her version; why it happened, how, what would be the appropriate reaction. The young boy’s cause is questioned, but even if accepted, his method is not. Apologies are then offered and accepted, forgiveness is demanded and offered. The young boy has to make up for the violation by doing free garden work for some time. The rich man and neighbours agree to contribute to the family’s medical expenses.

So, in the end, the story of the burglary is written in a way that is acceptable to all; the sheet of paper is then burnt; symbolizing an end to the burglary, but not to the aftermath.

This may be questioned as rewarding the burglar. However, if this restores all parties, reconciles them, and resolves the conflict, then this should be point.

Regardless, it may sound simple, but it is not. This approach requires deep knowledge and skills from the conflict/peace worker bringing the parties together, as does being the wise person who is chairing the session. There is rehabilitation for the victim, paying respect to his feelings, giving him voice & ear, apology and restitution. There can be manifestations of sorrow, even joint sorrow. A new structure is being built bringing people together who never met before, sharing the karma of this conflict, imbued with the culture of this way of approaching a conflict. There are efforts to see the acts in the light of extenuating circumstances; nature, structure, culture, with restitution and apology followed by forgiveness as integral parts. So are the elements of penitence and punishment that builds ties between victim and perpetrator. The karma element may also be at work in this approach.

The truth element is obvious, as that all parties have to tell their truths (making it easier for the perpetrator). This is also theatre : ho’o ponopono is a reconstruction of what happened, with the parties as actors, all acting jointly.

In short, Polynesian culture puts together what Western culture keeps apart. There is coherence to these processes, which gets lost in the Western tendency to subdivide and select, and more particularly to choose a punishment approach. So, perhaps a cul- ture that has managed to keep it all together is at a higher level than a culture that, out of this holistic approach to ‘after violence’ (including ‘after economic violence’), selects only a narrow spectrum?

Conclusion

Some conclusions flow naturally from these explorations. First, there is no panacea. Taken singly, none of these approaches are capable of handling the complexity of an ‘after violence’ situation; healing the widely diverse wounds, closing the violence cycles, reconciling the parties within themselves, to each other and to whatever higher forces that may exist.

One reason is that they are all embedded in dense nets of assumptions, some of which may be cultural.

Westerners would have no difficulty recognizing ho’o ponopono culturally specific, or ‘ethnic’, but tend to claim that theological and juridical approaches are universal, using Western = universal. However, human stupidity has to be tempered with human wisdom, which, in turn, has to be taken from wherever we can find it.

Cultural eclecticism is a must in the field of reconciliation, we cannot draw on any one culture alone; taken in combination these approaches may make more sense. The problem is to design the best combinations for any given situation, and that obviously requires knowledge, skill and experience. Some of the twelve belong quite naturally together, in twos and threes:

– the ‘blaming the circumstances’ approach (1): nobody is guilty, and the karma approach (5): we are all guilty/responsible, together, are perspec- tives that may have great conciliatory effect;

– the reparation/restitution approach (2) and the apology/forgiveness approach (3) complete each other, and may work if the case is not too hard;

– the penitence approach (4) and the pun- ishment approach (5) also complete each other, and may release the perpetrator from guilt;

– the historical approach (7) and the the- atrical approach (8) complete each other, providing an image of factual and poten- tial truths;

– the joint sorrow approach (9), the joint reconstruction approach (10) and the joint resolution approach (11) are based on the same methodology;

– the ho’o ponopono approach (12) is very holistic, in a sense incorporates all others.

As there is some validity to all approaches, why not try them all? There are good rea- sons to do this. The ‘blaming the circumstances’ approaches may blunt the trauma and the guilt, and pave the way for more symmetric approaches, with shared responsibility. Ho’o ponopono practiced within all sectors in a society might deepen that impact. The three ‘joint approaches’ (9, 10, and 11) could be initiated at an early stage, at a modest level, to gain experience. At the same time, history commissions and theatre groups will begin to operate. If someone has broken the law by committing crimes of war, against humanity, and genocide, they will of course have to be brought to justice, facing the State, the Community of States, and his/her God.

The time has then come for the two approaches that, together, give the meaning to the concept of reconciliation that most people usually have in mind: forgiveness, to the aggressor/perpetrator who deserves being forgiven. In a transaction, two-way traffic is required. What flows in the other direction is a combination of a deeply felt apology based on an undeniable truth, and restitution; in some cases to be televised nationally.

However, this transaction will only lead to healing-closure-reconciliation within a con- text of all the other approaches, as a crowning achievement. If attempted too early, it may fall flat, particularly if outsiders enter and say, ‘well, you surely have been through tough times, but it is all over now so why not shake hands and let bygones by bygones!’ Trauma, including the trauma flowing from guilt, may fill a person to the brim and beyond. Feelings that overwhelm the survivors have to be treated with respect, and respect requires time.

In all of this, two traditions have crystallized with clear contours: the priest and the judge. They carry prestige in society because they know the book that can open the gates to heaven or hell, or to freedom or prison. The other ten approaches are less professionalized if we assume that historians do not have a monopoly on truth, or playwrights on drama. For all approaches a versatile, experienced peace worker would be meaningful and helpful. He does not declare people as either damned/saved, or guilty/non-guilty. He is trying to help them come closer to each other, not to love each other, but to establish reasonable working relations that will not reproduce the horrors. The bitter past should become a closed book, what happened should be for- given but not forgotten. In doing so, he will have to work with the priest and the judge without letting the asymmetry of their ways of classifying human beings become his own.

One simplified, superficial, but yet still meaningful, way of doing reconciliation work is to invite the parties to discuss them. They all more or less know what happened, but may be divided over why, and what comes next. The twelve approaches are presented, possibly with the peace worker acting some of the roles. The parties around the table are then invited to discuss, and through discussion to arrive at the best combination for their situation.

In the present author’s experience this is possible, even in war zones. Furthermore, something important can occur: as they discuss reconciliation, some reconciliation takes place. The approaches begin to touch their hearts, even if the outer setting is only a seminar. Of course, this is nothing but an introduction to the real thing, but from such modest begin- nings waves of togetherness may spread – even from the most turbulent centres.

References

Galtung, J. (1998) 3R: Reconstruccion, Resolucion, Reconciliacion (3R: Reconstruction, Resolution, Reconciliation). Gernika: Gogoratuz.

1) Throughout this article the masculine terminology is used. Therefore ‘he’ should be read as ‘he/she’ and ‘his’ should be read as ‘his/her’.

2) A personal remark: doing six months in a Norwegian prison provided ample opportunity to reflect on the functions of punishment. Yes, I broke Norwegian law by refusing to do the punitive extra six months of a (to my mind) senseless alternative service. I wanted to do peace work. The imprisonment did not reform me; I would have broken the same law again. But I felt guilt, not for having broken a law, but for having broken the ties to family, friends, and fiancé. They said, don’t worry, we can take it, but some of that guilt remained.

Originally published in: Intervention 2005, Volume 3, Number 3, Page 222 – 234