Graham Greene in the Belgian Congo

My purpose in this contribution is to present and contextualize the only film footage ever recorded of the novelist Graham Greene (1904-1991) in the Belgian Congo in 1959. The footage was filmed with an 8mm camera, which did not record sound. It belongs to Mrs. Édith Lechat (née Dasnoy;1932-) and her husband, the leprosy specialist Doctor (later Professor) Michel Lechat (1927-2014).

From 1953 through 1960, Dr. Lechat was head of the leper hospital and colony of Iyonda, a village and mission station some 15 kms south of the city of Coquilhatville (now, Mbandaka) in central-western Congo. Greene stayed a number of weeks in Iyonda and other mission stations in the region in search of inspiration, a setting, and material for a new novel. The novel, A Burnt-Out Case, appeared in 1960, and was dedicated to Dr. Lechat. Greene occupied a room in the house of the missionary fathers in Iyonda, but spent long parts of his days with the doctor and his family. The film reached me through the hands of Édith Lechat, who had it transposed to a DVD-playable format, and via my friend Hendrik (a.k.a., “Henri” or “Rik”) Vanderslaghmolen (1921-), who was a missionary in the region at the time. As he was one of the only Belgian missionaries there with some knowledge of English, he often accompanied Graham Greene during his trips from one mission station to another. Rik Vanderslaghmolen and the Lechats are still close friends today.

Much of the information I offer below stems from conversations I had with both Rik Vanderslaghmolen and Édith Lechat in July and August 2013. Regrettably, Dr. Michel Lechat’s poor health condition did not allow me to probe his memory, but an interview he gave for the Brussels-based weekly The Bulletin on the occasion of Greene’s death in 1991 is available (Lechat 1991), as well as a closely similar talk he gave at the 2006 Graham Greene Festival in Berkhamsted, published in the London Review of Books in August 2007 (Lechat 2007). Édith Lechat has given me the kind permission to share the film with the readership of Rozenberg Quarterly and to add the necessary contextual information on both the historical situation and the contents of the film.

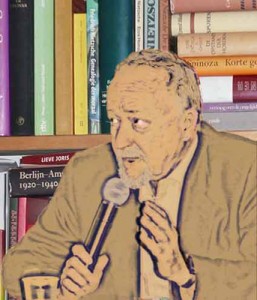

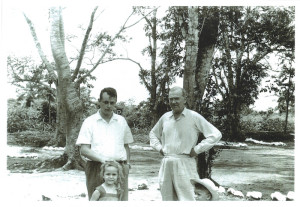

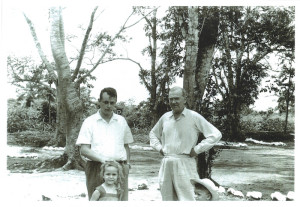

Graham Greene (right, 54 years old) with Dr Michel Lechat (31 years old) and Lechat’s two first-born children, Marie and Laurent. Car park in front of the airfield of Coquilhatville, the Belgian Congo, 5 March 1959. Photo reproduced with permission from Edith Lechat.

Snippets of the film were used in a documentary the BBC produced on Graham Greene in 1993 (The Graham Greene Trilogy, by Donald Sturrock). Yet, the order in which the documentary presented the snippets did not respect the original course of the film and they were, in any case, fragmentary. Also, neither the film bits nor the voice-overs in the documentary provided much information on Greene’s stay in the Congo and his relation with the Belgian missionaries, but rather served to portray Greene’s personality, i.e. to illustrate what some interviewees described as his tendency to falsely pretend happiness and gaiety while in reality being a sombre and depressed man, especially in those years. My contribution here is thus an opportunity to present, for the first time, the film in its full and unedited length, and to zoom in on the Congolese and missionary circumstances under which it was made.

Graham Greene’s journey to the Belgian Congo took place in the beginning of 1959; to be precise, he arrived by plane in Leopoldville (now, Kinshasa) on 31 January and left that city again for Brazzaville on 7 March 1959. He was in Iyonda from 2 to 11 February and again from 26 February to 5 March, visiting other mission stations in between these two periods. The reason why some 35 years later Greene wrote that “In 1959 I spent about three months in and around the leper colony of Iyonda in the then Belgian Congo” (Greene in Hogarth 1986: 108) and why in the same way he mentioned “months” in an interview heard in part 2 of the BBC documentary, remains unclear. His stay in the Congo must have appeared much longer to him with hindsight than it had been in reality. Either way, in 1958 he had a rough idea for a book in mind, namely a stranger arriving in a leper colony run by a missionary order. When Greene was searching for a suitable leper colony in a remote place of the globe which he could visit to substantiate his technical knowledge of leprosy and where he could spend time with missionaries, a mutual Belgian friend told him about Michel Lechat and his work in the Congo (Lechat 1991, 2007). He wrote three letters to the doctor, who in turn discussed it with the missionary fathers of Iyonda and Coquilhatville, and his stay was arranged.

The missionary congregation in charge of Iyonda, Coquilhatville, and the other mission stations Greene visited during his Congo journey was the Belgian branch of the Catholic Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (Missionnaires du Sacré-Coeur de Jésus, MSC), which included among its members the famed specialists and guardians of the Mongo people, Edmond Boelaert (1899-1966) and Gustaaf Hulstaert (1900-1990), and which produced the proto-scholarly and socially committed journal Æquatoria (1937-1962), later succeeded by Annales Æquatoria (1980-2009) (see Vinck 1987, 2012 and www.aequatoria.be for more details). The MSC missionaries and their bishop Mgr Hilaire Vermeiren (1889-1967) were particularly proud to receive the famous author, who had not only converted to Catholicism in his early twenties but some of whose books, such as Brighton Rock, The Lawless Roads, The Power and the Glory, The Heart of the Matter, and The End of the Affair, also developed profoundly Catholic themes.

Entrance to the Iyonda leprosery, with the missionary fathers’ house on the left, where Greene was accommodated. The first part of the 8mm film was recorded on the loggia of this house. Photo reproduced with permission from R. Vanderslaghmolen.

During his stay in the Congo, Greene kept a diary in which he noted down daily observations, thoughts and conversations, and in which he tried out some characterizations and pieces of story for the novel: “I took advantage of the opportunity to talk aloud to myself, to record scraps of imaginary dialogue and incidents, some of which found their way into my novel, some of which were discarded” (Greene 1968 [1961]: 7). Afterwards, the diary was thoroughly proofread by Dr. Lechat, who did not only correct technical errors related to leprosy and leprosy treatment but also cleaned out quite some painful descriptions of real people and situations, before it was published, in 1961, under the title In Search Of A Character: Congo Journal. It contains the dates and locations of Greene’s whereabouts, and mentions the various missionaries, colonials and other people he met on his way. In an article posthumously published in Annales Æquatoria, Gustaaf Hulstaert identified each MSC missionary mentioned in the diary and also attempted to find clues in A Burnt-Out Case (Hulstaert 1994). Hulstaert ends his article with a defence of his fellow missionaries, most of whom Greene had depicted in not so favourable terms in the diary and, less explicitly identified, in the novel as well. Greene had found many of them, although kind and hospitable (see also his words in Hogarth 1986: 108), not widely educated, rather naive and infantile, easily amused by college types of humour and immature games, some of them cruel with animals, others lazy, and all of them occupied with all sorts of logistics, such as constructing buildings, running schools, laying in provisions, but not with the spiritual fundaments and higher goals of motivated Christianity.

One of the exceptions was the bishop, Mgr Vermeiren. Greene and Vermeiren seem to have shared the same perception of the priests; testament to this is what Vermeiren wrote to the MSC provincial superior in Belgium in 1957: “It is my impression that quite a number of our priests are not mature. For people holding university degrees, they sometimes behave so childishly” (letter to Jozef Van kerckhoven, 26 April 1957, MSC Archives). In his diary, Greene appreciates Vermeiren for being “a wonderfully handsome old man with an eighteenth-century manner – or perhaps the manner of an Edwardian boulevardier” (Greene 1968 [1961]: 26), and lauds his cultivation as well as his bravery and tenacity in the difficult years of decolonization (1968 [1961]: 40; see also Hulstaert 1989). In the many years of professional and friendship contacts I have had with members of the MSC, I have learned that priests and friars who worked under Vermeiren are in general less eulogistic about him, remembering him especially for his aloofness and sense for pomp and rank – a characterization which also surfaces in biographical sketches such as Van Hoorick (2004: 26). This discrepancy is indicative of Greene’s general preference for patrician class and high-cultured milieus, and in any case suggests that his interpretive grid was considerably remote from the fathers’, leading more than once to a misunderstanding or at least to a lack of connection. This want of mutual understanding and connection is also mentioned by Hulstaert (1994: 501-502) and was similarly reported to me by Rik Vanderslaghmolen and Édith Lechat.

One of the MSC missionaries working in the Congo was Martin (Adolf) Bormann Jr. (1930-2013), first-born son of Adolf Hitler’s private secretary Martin Bormann, and Hitler’s godson. Converted to Catholicism at the age of 17, he studied theology and was ordained priest in 1958, in the Austrian-German branch of the MSC (MSC 1963: 255). He went to the Congo for the first time in May 1961, where he was assigned to the mission station of Mondombe, in the easternmost diocese of the MSC mission region, some 800 kms east of Iyonda and Coquilhatville. In 1964, fleeing the advancing Simba rebels, he lived for some days hidden in cassava fields, but was nonetheless caught (Bormann 1965, 1996). In November 1964, he was freed by Belgian paratroopers and repatriated to Europe. He went back to the Congo for a second term of one year in March 1966 and left priesthood in 1971. On 12 February 1959, the day when Greene arrives in the mission station of Bokuma, located some 70 kms northeast of Iyonda but still some 700 kms away from Mondombe, he writes “Incidentally Martin Bormann’s son is somewhere here in the bush” (1968 [1961]: 44-45). However, in 1959 Bormann had not yet arrived in the Congo. An explanation for this confusing anachronism in Greene’s diary is to be found in the fact that, as Édith Lechat and Rik Vanderslaghmolen reported to me, Martin Bormann’s entrance in the congregation of the MSC and his being assigned to the missions in the Belgian Congo raised some dust among missionaries and colonials in the vicariate of Coquilhatville. In 1959, Bormann’s anticipated arrival was, in fact, the talk of the town in Coquilhatville and depending mission stations. Greene must have picked up the news and misinterpreted it, believing Bormann had already arrived.

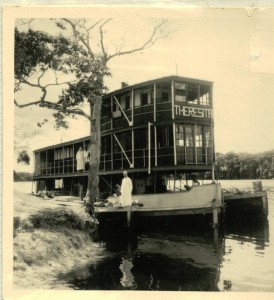

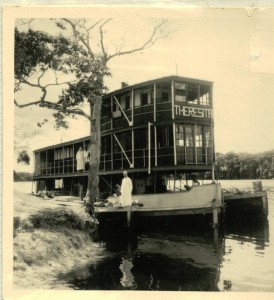

A Burnt-Out Case is set in a leprosery in the Belgian Congo and has as one of its protagonists a Belgian doctor (Dr. Colin), head of the leprosery, who, moreover, works in close collaboration with a group of missionaries, whose personalities and characters conjure up the MSC missionaries Greene met during his journey. In his dedication of the novel to Dr. Lechat (Greene 1977 [1960]: 5), Greene insists that the leprosery in the novel is not literally the one in Iyonda, even if he may have copied “superficial characteristics” from it. He also avers that Dr. Colin is not Dr. Lechat: apart from the fact that he has the same experience of leprosy, the character is in “nothing else” based on him. As far as the missionaries are concerned, Greene admits that he gave the Superior of the mission station to which the leprosery is attached in the novel, the same habit of smoking one cheroot after the other and of spilling ashes on everything and everyone in his vicinity as he had seen the Superior in Iyonda, Pierre Wynants (1914-1978), do. Also, Greene says the river boat on which the main character Querry, and later Parkinson, travel to and from the leprosery is inspired by the steamer which Mgr Vermeiren had put at his disposal in 1959 and on which he was often accompanied by Rik Vanderslaghmolen. But apart from that, Greene insists, none of the central characters is based on any particular person he had met in the Congo, and the novel “is not a roman à clef, but an attempt to give dramatic expression to various types of belief, half-belief, and non-belief, in the kind of setting, removed from world-politics and household-preoccupation, where such differences are felt acutely and find expression” (Greene 1977 [1960]: 5). Yet, however much I agree that reading A Burnt-Out Case as a roman à clef would severely miss the author’s point and defeat the purpose of the artistic experience, there do seem to be closer resemblances than Greene admits.

The river steamer Theresita, property of the MSC missionaries in the Congo and used by Graham Greene in 1959 to move from one mission station to another. Photo reproduced with permission from R. Vanderslaghmolen.

First of all, much like Greene, Querry, too, defends himself against allegations, from Marie, that the story he is telling her would be an allegory of his past and that he would be the boy appearing in it. Querry retorts to her: “They always say a novelist chooses from his general experience of life, not from special facts” (Greene 1977 [1960]: 152). Greene could have spoken exactly the same words in defence of A Burnt-Out Case. Secondly, Querry displays the same lack of impatience with what he feels to be the priests’ mediocrity as Greene shows in his diary, and both Greene and Querry are sickened by the fondness for gratuitous game hunting of one particular missionary, who, moreover, is both in the novel and in real life the captain of the river steamer (real person: Georges Léonet, 1922-1974). Thirdly, the bishop in the novel is depicted as an aristocratic and highly refined gentleman. He is described as “an old-fashioned cavalier of the boulevards” (Greene 1977 [1960]: 64), which is no less than an immediate echo of the words “Edwardian boulevardier” Greene used in his diary to describe Mgr Vermeiren. What is more, the bishop in the novel is a fond player of bridge (1977 [1960]: 64). The diary does not make mention of Vermeiren’s avid passion for this card game, but this passion is still legendary among MSC members today – not in the least Rik Vanderslaghmolen, who was often summoned to drive Mgr Vermeiren to outlying bridge venues. Fourth, in the same way as Greene is on record for having been a womanizer, drawing much of his success with the other sex from his fame (i.a., Shelden 1994), Querry, too, looks back on a life in which his status and celebrity as an artist-architect earned him considerable attention from women. Fifth, Greene was already world-famous before his departure to the Congo, and as the anticipation of too much attention annoyed him greatly, he travelled in the Congo under the pseudonym “Mr. Graham” (Lechat 1991, 2007). In the diary, Greene more than once noted down his irritation with admirers, mostly Belgian colonials, who in spite of his attempted anonymity managed to approach him to discuss literary matters or submit creative writings of their own to his appreciation and advice. Michel Lechat recounts the funny anecdote of how Greene, upon spotting from far an admirer driving in the direction of the leprosery, would run into the Lechats’ house, jump out of the rear window of their bedroom, and run away into the forest (Lechat 1991, 2007). Querry, too, is an internationally renowned artist, whose success and praises have worn him out. In fact, the very reason for his leaving Europe and hiding away in the Congo is his self-unmasking as a second-rate artist and his related desire to vanish from sight. The nail in Querry’s coffin is Mr. Rycker, Marie’s husband and a Belgian colonial entrepreneur relentlessly exasperating Querry with tributes and references to his grand artistic achievements. Again, the resemblance between Querry and Greene is too striking to be left unnoticed. Lechat in fact also remembers a number of other anecdotes and actual situations that befell Greene in the Congo and that are almost literally lived by Querry in the novel (Lechat 1991, 2007). Decidedly, as the biographer Norman Sherry put it, “in describing […] Querry, Greene is describing himself” (Sherry 2004: 194), and much more so than the novelist was prepared to recognize.

A Britain-based author of many novels set in tropical places, who goes to the Congo in order to find inspiration for a new book, travels the Congo river or its tributaries on a steamer, keeps a Congo diary in preparation of the book, and, in his literary creation, connects outer-world removal from all things familiar with inner-world self-confrontation, despair, and madness – one cannot help being reminded of Joseph Conrad and his Heart of Darkness and An Outpost of Progress (for Conrad’s Congo diary see Najder 1978 and also Stengers 1992).

Evidently, in terms of writing style, no two authors could be more unlike than Greene and Conrad. Although both privilege themes of gloom, failure, and disillusion and even though they both gauge the characters’ psychological and emotional states and changes (see also Stape 2007, among others, on Conrad’s heritage in Greene’ s work), Greene’s style is much less oriented towards sensuality and sensation, is story-practical, and is above all narrative- and action-driven whereas Conrad’s is description-based. Of more importance is the fact that, and the ways in which, Greene invokes Conrad on more than one occasion in his Congo diary. The diary entries reveal how heavily Conrad’s shadow had been hanging over Greene since his first days as a novelist.

First of all, we find several appropriate but terse and spontaneous citations from Heart of Darkness in the diary. When contemplating Leopoldville, Greene briefly cites, without any identification of the self-evident source: ““And this also”, said Marlow suddenly, “has been one of the dark places of the earth”” (Greene 1968 [1961]: 15). And when admiring the Congo river at Iyonda, he writes down “This has not changed since Conrad’s day. ‘An empty stream, a great silence, an impenetrable forest.’” (1968 [1961]: 18). We later on learn that Greene has found his Congo journey to be a perfect occasion to reread Heart of Darkness. In itself, this is not particularly noteworthy, as many a European has done the same when travelling to the Congo for the first time. What is of interest is that, on the day of 12 February 1959, Greene confesses that in 1932, i.e. at the age of 28 already, he had abandoned reading Conrad altogether, because it filled him with a strong sense of inferiority as a writer: “Reading Conrad – the volume called Youth for the sake of The Heart of Darkness – the first time since I abandoned him about 1932 because his influence on me was too great and too disastrous. The heavy hypnotic style falls around me again, and I am aware of the poverty of my own” (1968 [1961]: 42).

At that young age, Greene thus stopped reading Conrad – “that blasted Pole [who] makes me green with envy”, as he once referred to him (Keulks 2006: 466) – in order to avoid the risk of being too much influenced by him. Could this be where we have to find the origins of Greene’s strongly opposite writing style, a style he developed in reaction to Conrad’s, which he held in great awe and at the same time considered unattainable? Édith Lechat recalls how she and her husband once mentioned their great keenness for Conrad in a conversation with Greene, and how his reaction was unusually evasive and crabby. So crabby that the three never raised the subject Conrad again. Fascinatingly, a bit later, when he has progressed further in the book, Greene makes a new assessment of the novel as compared to his reading of it in his twenties: “Conrad’s Heart of Darkness still a fine story, but its faults show now. The language too inflated for the situation. Kurtz never comes really alive. […] And how often he compares something concrete to something abstract. Is this a trick that I have caught?” (Greene 1968 [1961]: 44). Whether one agrees with Greene’s appreciation or not (at least as far as Kurtz is concerned, I do), what we seem to be witnessing here is a moment later in Greene’s life at which he overcomes his self-degrading veneration of Conrad. The 54-year old, mature Greene, now rereading Heart of Darkness “as a sort of exorcism” (Lechat 1991: 16), has found faults in Conrad’s characterizations and has discovered a stylistic trick he believes he was overusing. These demystifying discoveries seem to enable Greene for the first time in his life to step out of Conrad’s overpowering shadow, to free himself from the burden of his inescapable ubiquity, now undone.

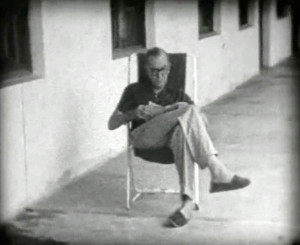

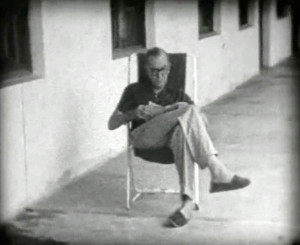

8mm film of Graham Greene in Iyonda, the Belgian Congo, 5 March, 1959. Reproduced with permission from Edith Lechat and Rik Vanderslaghmolen.

Click video to play. Click lower right corner of video to enter full screen. Press “escape” to exit full screen. Note: We are aware of an issue with this video in some internet browsers and are working on a solution.

The camera for this 8mm film was held by Father Paul Van Molle (1911-1969), the later superior of the Iyonda mission and leper colony. Greene mentions Father Paul only once, and briefly, in his diary, namely on 10 February, when receiving a haircut from him (1968 [1961]: 38). Greene himself does not mention or allude to the filming in his diary in any way. On the basis of a series of clues, Édith Lechat has been able to reconstruct that the filming took place in the morning and at lunch time of Greene’s last day at Iyonda, namely Thursday 5 March 1959. Later in the afternoon, the Lechat family would drive Graham Greene to the airfield of Coquilhatville, where he was to board a plane to Leopoldville. With Greene’s departure imminent, Father Paul realized the fathers and the Lechat family had not yet captured his presence among them on film, and therefore hastened to do so.

The film as shown here was not edited: all ‘cuts’ are moments at which Paul Van Molle switched the camera off and on again. The film, 4 minutes and 40 seconds in length, can be said to consist of two main parts, each filmed at a different time of the day and at a different location in Iyonda. The first part, running until 2’19”, is shot in the morning time on the loggia, named barza in Belgian colonial parlance, of the fathers’ house, where Greene was accommodated (see also photo of Iyonda above). The second part, running from 2’23” until the end, is an hour or two later, i.e. at lunch time, in the Lechat house, which was a few hundred meters away from the fathers’ house. On 27 February, Greene writes that “I no longer bother to go to the Congo [river] to read” (1968 [1961]: 66), a habit he used to entertain during his first stay in Iyonda from 2 to 11 February. The first twelve seconds of the film show Greene stretched out in a deck chair on the fathers’ barza reading a book, which according to the diary must be Belloc’s Catholic testimony The Path to Rome (1968 [1961]: 76). The fact that he is doing his daily reading there, and not on the banks of the Congo river, confirms that the film was recorded during Greene’s second stay in Iyonda.

The other details of the first part of the film are as follows. After 0’12”, we see that Greene has put the book aside and is engaged in a conversation with whom we discover a bit later to be Édith Lechat, then 27 years old, standing on the edge of the barza. Shortly after that, Father Rik Vanderslaghmolen, aged 38, joins in from behind Greene. As I mentioned above, Rik was one of Greene’s main escorts during his Congo journey, and in that capacity his name reappears quite frequently in the diary. At the time of Greene’s visit, Vanderslaghmolen was on leave in Iyonda to recover from illness (see also Hulstaert 1994: 498). Both the film and the diary show a Vanderslaghmolen as his family, confreres, and friends, including myself, know him best, namely as a frolicsome practical joker, an impish leg-puller, an ever good-humoured, jesting entertainer. As the three are having an amicable, relaxed conversation, Greene remaining seated, the zoom is close enough for an experienced lip reader to decipher what Greene is saying, probably in (broken) French, the language in which he habitually conversed with Édith Lechat (whereas he mostly used English with her husband). From 0’32” through 0’39”, Greene is entertained by the Lechat children, Marie (4.5 years old) and, on his little tricycle, Laurent (2.5). Then, from 0’39” to 0’45”, Greene is filmed holding a camera to photograph the cameraman, Rik stepping in and whimsically hindering Greene from looking into the camera viewer. After that (0’46” – 0’58”), Greene and Rik are larking about, Rik blocking the door of the house to prevent Greene, clutching his inseparable whisky flask, from coming in. In the following bit, until 1’13”, we first see Greene with Édith Lechat, lighting a cigarette, and her two children, immediately followed by Rik and Greene sillily engaged in a mock waltz, a stunt clearly triggered by the filming occasion. Next (1’13” – 1’20”), Rik amuses his company by trying to squeeze his lofty body into little Laurent’s tricycle. After Greene picks up his book and glasses and regains his deck chair, and Édith Lechat, following her daughter, leans through a window of the fathers’ house to have a conversation with someone inside, Dr. Lechat has joined the company and a chat ensues between the three (until 2’19”), Greene still seated, Michel and Édith Lechat standing. Michel Lechat’s and Greene’s gazes (1’56” – 1’59”) reveal a light, good-hearted annoyance with the camera’s intrusion.

The second part of the footage is shot in the house of the Lechats, showing Greene with the Lechat family at lunch, assisted by their Congolese servant Mongu Henri (year of birth unknown). This takes place only a few hours after the morning scene at the fathers’ house. It can be noticed, however, that Greene has changed shirts, possibly in anticipation of his flight to Leopoldville (notice that it is the same shirt as in the photo above, taken in the car park at the Coquilhatville airfield). Gazes into the lens and nervous laughter make it clear that the company, although trying to behave naturally, remain acutely aware of the camera’s presence during the entirety of the meal. My poor lip reading skills aside, I venture to say that at 3’36” – 3’38”, Mrs. Lechat, slightly embarrassed, addresses the cameraman with the words“Père Paul, arrête! Arrête de filmer, s’il te plaît!” (“Father Paul, stop! Stop filming, please!”). Between 3’16” and 3’20”, we witness Dr. Lechat repairing his photo camera, the same camera with which, a few hours later, his wife would take the picture in the airfield car park.

The second half of the 1950s was one of the darkest periods in Greene’s life, specifically after the break-up with his mistress Catherine Walston (i.a., Shelden 1994; Sherry 2004; R. Greene 2008). His manic depression reached the most severe point he had experienced until then, he self-reported to feel chronically miserable, even to have turned into a misanthrope. In the BBC documentary, relations and friends of Graham Greene’s narrate how he was an absolute master in masking away this gloominess and dejection, concealing it under the exact opposite – merriment, smiles, superficial gaiety. Appearing in off-screen voice, his wife Vivien Greene explains that: “I’ve discovered, and I’m sure I’m right, that people who are great on practical jokes are very unhappy. And I think it was when Graham was most unhappy that he started all these practical jokes. […] It was I’m quite sure when he was most deeply unhappy that he had this spell of practical joking, which people think of as high spirits but I don’t think it is.” Her off-screen voice is heard over (very short) bits of images showing Graham Greene dancing around with Rik Vanderslaghmolen on the fathers’ barza and looking happily entertained at lunch with the Lechat family. The message of the documentary makers is clear: Greene’s gaiety and insouciance visible on the Congo footage are make-believe, a shallow pose that when scratched away reveals a deeper, lurking despondency. I do not wish entirely to refute this analysis, but at the same time would like to invoke the album, also mentioned above, that the graphic artist Paul Hogarth made on the locations appearing as settings in Greene’s novels (Hogarth 1986).

In commentaries Greene added to Hogarth’s paintings in this album, the novelist remembered his time in Iyonda as not particularly gloomy: “It was not a depressing experience. […] Most of my memories of the léproserie are happy ones – the kindness of the fathers and friendship of Dr. Lechat to whom the book is dedicated” (Greene in Hogarth 1986: 108-112). Certainly, the late 1950s were dark, dismal years in Graham Greene’s life, and to be sure the writing of A Burnt-Out Case constituted a terrible artistic ordeal for him – as he put it: “What was depressing was writing the novel and having to live for two years with a character like Querry. I thought it would be my last novel” (Greene in Hogarth 1986: 108). But perhaps the time he spent in the Congo with Dr. and Mrs. Lechat and with the fathers, among whom the comic and generous teaser Rik Vanderslaghmolen, who according to Édith Lechat was “the only person really capable of making Graham Greene laugh and have fun”, triggered off tiny bouts of contentment in Greene’s tormented soul. A contentment surely initiated from the outside, and maybe ephemeral and fleeting, but nonetheless momentarily highly efficacious.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely wish to thank Édith Lechat and Rik Vanderslaghmolen for all the information, feedback, and viewpoints they so kindly offered me. Both of them have given their approval to this text. My gratitude also goes to Honoré Vinck for his assistance with a number of archival issues and to Jürgen Jaspers.

REFERENCES

Bormann, Martin. 1965. Zwischen Kreuz und Fetisch: Die Geschichte einer Kongomission. Bayreuth: Hestia.

Bormann, Martin. 1996. Leben gegen Schatten: Gelebte Zeit, geschenkte Zeit. Begegnungen, Erfahrungen, Folgerungen. Paderborn: Bonifatius.

Greene, Graham. 1968 [1961]. In Search of a Character: Congo Journal. London: Penguin.

Greene, Graham. 1977 [1960]. A Burnt-Out Case. London: Penguin.

Greene, Richard (Ed.) 2008. Graham Greene: A Life in Letters. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Hogarth, Paul. 1986. Graham Greene Country: Visited by Paul Hogarth, Foreword and Commentary by Graham Greene. London: Pavilion.

Hulstaert, Gustaaf. 1989. Vermeiren (Hilaire). Biographie Belge d’Outre-Mer – Belgische Overzeese Biographie 7(C): 365-368.

Hulstaert, Gustaaf. 1994. Graham Greene et les missionnaires catholiques au Congo Belge. Annales Æquatoria 15: 493-503.

Keulks, Gavin. 2006. Graham Greene. In Kastan, D. S. (Ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature, 466-471. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lechat, Michel. 1991. Remembering Graham Greene. The Bulletin: The Newsweekly of The Capital of Europe, 18 April 1991: 14-16.

Lechat, Michel. 2007. Diary: Graham Greene at the leproserie. London Review of Books 29(15): 34-35.

MSC (Missionnaires du Sacré-Coeur de Jésus). 1963. Album Societatis Missionariorum Sacratissimi Cordis Jesu, A Consilio Generali Societatis ad modum manuscripti pro Sociis editum. Rome: MSC.

Najder, Zdzislaw (Ed.) 1978. Congo Diary and Other Uncollected Pieces by Joseph Conrad. New York: Doubleday.

Shelden, Michael. 1994. Graham Greene: The Man Within. London: Heinemann.

Sherry, Norman. 2004. The Life of Graham Greene, Volume 3: 1955-1991. New York: Viking.

Stape, John. 2007. The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad. New York: Bond Street Books.

Stengers, Jean. 1992. Sur l’aventure congolaise de Joseph Conrad. In Quaghebeur, M. & Van Balberghe, E. (Eds), Papier blanc, encre noire: Cent ans de culture francophone en Afrique centrale (Zaïre, Rwanda et Burundi), 15-34. Brussels: Labor.

Van Hoorick, Walter. 2004. Hilaire Vermeiren: De tweede Beverse missiebisschop (1889-1967). Land van Beveren 47(1): 11-30.

Vinck, Honoré. 1987. Le cinquantième anniversaire du Centre Æquatoria. Annales Æquatoria 8: 431-441.

Vinck, Honoré. 2012. Ideology in missionary scholarly knowledge in Belgian Congo: Æquatoria, Centre de recherches africanistes; The mission station of Bamanya (RDC), 1937-2007. In Harries, P. & Maxwell, D. (Eds), The Secular in the Spiritual: Missionaries and Knowledge about Africa, 221-244. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

About the author

Prof.dr. Michael Meeuwis is Professor of African languages and linguistics at Ghent University, where he is also the director of the Centre for Studies in African Humanities ( http://www.cesah.ugent.be/ ).

His domains of interest include the grammatical description of Lingala, the sociolinguistics of Lingala, the history of colonial linguistics in the Belgian Congo, South African sociolinguistics, issues related to language and identity in sub-Saharan Africa, and description and theory formation in pragmatics. His continuously updated list of publications can be consulted at https://biblio.ugent.be/person/801001653606; his personal page is to be found at http://www.africana.ugent.be/node/208

See also: http://grahamgreenebt.org/

See also: http://www.aequatoria.be/

Matt Essieh is my name, born in Sampa which is a village on the border with Ivory Coast. I loved school but had to stop at age twelve after completing middle school. My parents were very poor, even so that I had to live as an altar boy at the Catholic mission. My parent’s house was literally too small for all their children and you know that we Africans can improvise! So I grew up at the mission. After middle school I went across the border into Ivory Coast and stayed with an aunt. It was my own idea and the only way I knew to find money to further my education for which I have a passion. Yes so my plan was to do odd jobs and so raise enough money to support myself through secondary school. I decided on moving over the border into another country because in those days the economy over there was better. It was for example possible to earn money delivering loads at the local market with your wheel barrel and I also sold ice-cream with one of these bicycles with a cold box up front. I was willing to do everything. I cleaned tables in one of the hotels and many other ‘by-day’ jobs, whatever I could find.

Matt Essieh is my name, born in Sampa which is a village on the border with Ivory Coast. I loved school but had to stop at age twelve after completing middle school. My parents were very poor, even so that I had to live as an altar boy at the Catholic mission. My parent’s house was literally too small for all their children and you know that we Africans can improvise! So I grew up at the mission. After middle school I went across the border into Ivory Coast and stayed with an aunt. It was my own idea and the only way I knew to find money to further my education for which I have a passion. Yes so my plan was to do odd jobs and so raise enough money to support myself through secondary school. I decided on moving over the border into another country because in those days the economy over there was better. It was for example possible to earn money delivering loads at the local market with your wheel barrel and I also sold ice-cream with one of these bicycles with a cold box up front. I was willing to do everything. I cleaned tables in one of the hotels and many other ‘by-day’ jobs, whatever I could find.