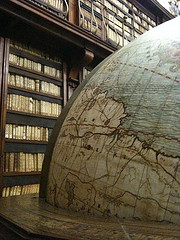

South Lebanon – Photo by Nicolien Kegels

“National liberation, national reawakening, restoration of the nation to the people or Commonwealth, whatever the name used, whatever the latest expression, decolonization is always a violent event.” – Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 1.

In order to understand Hezbollah’s political and social project it is crucial to start by placing the movement within the wider context of Middle Eastern conflicts. The Palestinian cause and the failure of the Arab nationalist experience of Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 1950’s and 1960’s in addition to the colonial experience which determined the region’s maps, borders and current political identities are all necessary components of Hezbollah’s political discourse. To this day, Palestine remains central in Arab political concerns and being Arab remains a political and ideological position that is in constant flux.

I will argue that the emergence of Hezbollah and subsequently their political discourse must be understood in relation to three main issues of contemporary Arab history:

a. the post-colonial liberation struggle for the establishment of independent political entities and identities (with Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Arab Nationalist experience as its most salient example);

b. the resurgence of Islam as a political force after the failure of secular Arab nationalism;

c. and the specifically Shiite political experience from the Iranian Revolution to the emergence of Hezbollah out of the Lebanese Shiite condition.

South Lebanon

In this essay, written in 2012, I will present the context for the emergence and development of Hezbollah’s political discourse. The preceding three conditions will be investigated in order to better understand the discourse and identity that this Islamic movement is promoting in Lebanon and the Arab world. After exposing the context of emergence and decline of Arab nationalism, the rise of political Islam as a response, and the specific experience of Shiite political movements in Lebanon, I will show how Hezbollah’s political discourse transformed from an uncompromising Shiite militia in the 1980’s to a Lebanese political party and resistance movement in the 1990’s and with the liberation in 2000, to a regional force after the 2006 war.

Looking at the political landscape in the Middle East today, one can notice that the same political divisions of the early post-colonial time remain at the heart of current conflicts between the pro-Western “moderate Arab states” and the anti-Western “axis of refusal”. In fact, since the end of European direct colonial rule over the Arab world, two opposing camps emerged that were to mirror the global division of the Cold War between a revolutionary socialist pro-Soviet camp and a reactionary pro-Western one (Kepel 2006, 46). The first group adopted a revolutionary rhetoric refusing western influence and preaching armed resistance against the Israeli occupation of Arab lands and a refusal of the Western post-colonial influence. This group led by Nasser’s Egypt in the 1950’s and 1960’s was mobilizing the Arab masses with a discourse of Arab nationalism and socialist reforms. On the other side, were the monarchical regimes of the Gulf, Jordan, pre-revolutionary Iraq and Tunisia. This pro-Western camp was concerned in preserving the status quo and curtailing the advancement of Arab nationalism and socialism into their societies.

While the revolutionary camp gave way to what is now usually referred to as the “axis of refusal” now formed mainly of the alliance between Iran, Syria, Hezbollah, and Hamas (EL Husseini 2010), the monarchical camp gave way to what is now called the “moderate states” which now includes in addition to the previous pro-Western states, Egypt[i]. Since Nasser, the first camp has been more successful in representing the popular will and appealing to the general populations while the second camp has managed to sustain its interests despite its general lack in popularity. The fall of Arab nationalism and the emergence of religious discourses and sectarian divisions especially after the Iranian Revolution and the second Gulf war led to this division becoming somewhat of a religious war between a Sunni camp (the “moderate” Arab states) and a Shiite one (the “axis of refusal” which also includes non-Shiite components). This is not to say that religious divisions do characterize the conflict between the two, however, one of the mainstream discourses emerging do represent it this way. My argument is that the conflict is essentially a political one between two forces with opposite programs and visions of society and the relation with the Western other.

I will argue that Hezbollah as a movement that belongs to the “axis of refusal” is one of many movements – religious in most parts – that emerged on the ruins of the Arab nationalist experience with a discourse that rejected the secularist ideas of Nasser and re-articulated an anti-colonial discourse with an Islamic essence. For this reason, I will start my analysis of Hezbollah with a historical context that traces the emergence of Arab nationalism and its failure in order to better understand the conditions of emergence of political Islam and its Shiite variant in Hezbollah.

The emergence of Hezbollah can be read through a number of socio-political, cultural and economic transformations that shaped the conditions for political Islam to emerge as the hegemonic force of resistance in various forms. As Mohammed Ayoob contends “Hizbullah and Hamas are part of a larger trend that has come to combine nationalism with Islam in the Arab world since the 1970’s” (Ayoob 2008, 114). Many scholars have traced the emergence of new Islamic political forces as a reaction to the 1967 defeat and the failure of secular Arab nationalism.

Ayoob continues “Political Islam thus became a surrogate for nationalist ideologies, seamlessly combining nationalist and religious rhetoric in a single whole. Francois Burgat observes, ‘Much more than a hypothetical ‘resurgence of the religious,’ it should be reiterated that Islamism is effectively the reincarnation of an older Arab nationalism, clothed in imagery considered more indigenous” (ibid, 114).

Furthermore, Islamism must be understood not as a movement backwards or as many have argued an anti-modern phenomenon, but to the contrary. Political Islam in many of its various forms is as Michael Watts argues “a conspicuously modern phenomenon” (Watts 2007, 192). In fact, Graham Fuller argues that as today’s most influential political discourses in the Arab world, Islam(s) seem to be preoccupied with the same economic, social, and political issues that move much of the political debates in the developing world (Fuller 2004, xix, 67, 81). The author writes that “Islamists are struggling, like so much of the rest of the developing world, with the genuine dilemmas of modernization: rampant change of daily life and urbanization at all levels, social dislocation and crisis, the destruction of traditional values, the uncertain threats of globalization, the need for representative and competent governance, and the need to build just societies and to cope with formidable political, economic, and cultural challenges from the West” (ibid, xii).

Fuller’s argument is precisely that political Islam as he says “is not an exotic and distant phenomenon, but one intimately linked to contemporary political, social, economic and moral issues of near universal concern” (ibid, xii).

This essay and my project in general have precisely this aim: to de-exoticize Hezbollah by presenting it as a political movement with a complex set of demands and articulations that are rooted in economic, political and cultural conditions often shared in many parts of the world. By exposing the conditions that led to the emergence of Hezbollah as a political movement and the conditions that led to this movement to adopt the set of demands and political identities that they promote, I will argue that looking at militant political Islamic movements only as terrorist groups hinders any possibility of understanding these groups.

The rise and fall of Arab Nationalism

Being Arab has not always referred to a political group identity for those people living in what is called the “Arab world” – the land stretching from the Atlantic Ocean meeting North Africa to the Gulf Sea[ii]. Ever since an Islamic Caliphate represented authority in what is now the Arab world, it was the power of Islam that consolidated the different groups living under the banner of the Islamic Empire[iii]. Within the widely diversified Empire, individual group identities took the shape of tribe, clan or ethnic affiliations which were often an obstacle to the emergence of national identities (Dawisha 2005, 86). In fact, if any Arab political entity ever existed, it was never distinct from Islam as its forging force. Thus, it was not Arabism that constituted the identity of the two Arab dynasties that succeeded Mohammed (the Umayyad and the Abbasid), but their authority to represent the power of Islam and thus lead the Umma[iv].

Therefore, Arabism did not justify any distinct political identity before the notion of nationalism as a secular cultural identity, was articulated by Arab intellectuals within the Ottoman Empire in late 19th century[v]. As an idea, the first articulation of Arab nationalism can be linked to the emergence of a class of intelligentsia among Arab speaking peoples (mainly in Syria where a large number of Christian Arabs live) influenced by European modernity and Enlightenment (ibid, 40). These intellectuals were educated in European missionary schools, widely spread in this area at the time, or in Europe. Therefore they were influenced by the growing ideas of nationalism and modernity spreading there (Zein 1979, 60)[vi]. Zein argues that these articulations appeared in the late decades of the 19th century as a reaction to the growing Turkification of the Ottoman Empire (ibid, 55-80).

The outcome of the Great War (1914-1918) provided a new motivation for the Arab nationalists. The promises of an independent Arab state made to Sharif Hussein of Mecca by the British in exchange for him fighting the Ottomans were not kept and the Sykes-Picot[vii] accord between the French and the British – the victors of the war – would introduce a new factor to the Arabs and the Arab nationalist narrative: colonialism. The Sykes-Picot accord divided the Arab lands of the former Ottoman Empire into nation-states under the authority of one of the two victors. Thus, the accords became a symbol of colonial domination over the Arab ‘fatherland’ and the betrayal of the West[viii]. The “Arab Cause” will no longer be independence from Ottoman rule, but the re-unification of the [lost] ‘Arab nation’ and the liberation from colonial domination. In other words, the outcome of the Great War was the transformation of the Arab nationalist movement into an anti-colonial one something that remains a crucial component of the Arab nationalist identity (see also Khalidi et al. 1991).

However, it was not until the 1950’s that Arab nationalism overcame its status as an elitist movement and achieved the status of a mass movement and a hegemonic narrative of identity. With the revolution in Egypt (1952) and the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser to power (1954), Arab nationalism assumed a considerably different articulation compared with that of its early theorists. One crucial issue that would be added to the anti-colonial stance of the Arab nationalist discourse was the emergence of the State of Israel on the ruins of Palestine in 1948 as another episode of the colonial project.

In the following paragraphs, I will examine the shifts on political, social, economic and cultural levels that facilitated Nasser’s articulation of Arab nationalism to make Arab the hegemonic identity in the ‘Arab world.’ Nasser’s project of a secular Arab nationalism would collapse on the battlefields of the 1967 war with Israel opening the way for the emergence of new movements. I will argue that in addition to the transformations on the social and economic fields, the radio played a fundamental role in spreading Nasser’s narrative to Arab populations beyond the Egyptian borders allowing it to influence the way people in the Arab world defined themselves and their identity.

Consolidating the Arab Nation

In 1952 the Egyptian Khedive was overthrown after a revolution led by the “Free Officers” of the Egyptian army. The two leading figures of this group were Muhammad Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser. The former would become the first president in 1953 and would be replaced in 1954 by Nasser after an internal power struggle. Nasser, a young, dynamic and charismatic figure, would quickly become the symbol of the Arab-socialist revolution. The “Free Officers” started mainly as a reaction to the corruption of the post-colonial government and its failure to provide a social, economic and political independence to the country; these officers rejected the continuous exploitation of Egypt’s wealth at the hands of the ex-colonizers and their local agents. The movement was also motivated by another factor, namely the defeat of the Arab armies in the 1948 war against the newly formed state of Israel. Nasser and his companions all participated in this war, and their ideals were forged – as Nasser himself later wrote in his book The Philosophy of the Revolution – on its battlefields. They blamed the inter-Arab ruling class rivalry for the defeat of the Arab armies and the colonizers for their support of their last colony: Israel[ix].

Once in power, Nasser endorsed a transnational project of Arab nationalism, a message that he enthusiastically spread throughout the Arab world. He invested large sums of money to create what became the Arab world’s largest broadcasting system. Nasser was clearly aware of the power of Radio to gather Arab masses and his aim to reach these masses would take form in the station associated with his name: Sawt el Arab (the Voice of the Arabs). The station was launched in 1953 as a project supervised by Nasser himself (Boyd 1975, 646). Its goal was to reach all the Arabs ‘from the ocean till the sea’ and propagate the narrative of Arab nationalism and socialism; the channel would give Nasser access to Arabs outside of Egypt expanding his power base beyond nation-state borders and making him the leading figure for Egyptians and non-Egyptians alike. Shortly after its launch, Sawt el Arab became the most popular channel in the Arab world with a reach extending from Morocco to the desert of Saudi Arabia (Dawisha 2005, 148-9).

Adeed Dawisha writes that, “If national identity emerges as a result of purposeful narrative, then it is essential to comprehend accurately when the narrative began, for its later development and contemporary impact has to have something to do with the intellectual, ideological, and political influence under which it emerged” (ibid, 16).

The rise of the Arab nationalist narrative of Nasser to the forefront of popular movements in the 1950’s and 1960’s is a result of multiple transformations that occurred in the Arab territories since the late days of the colonial rule. In this context, radio was the medium that for many reasons was bound to be the vehicle of the Arab nationalist narrative. Whether for cultural, social or technological reasons radio was the perfect medium to articulate an identity itself based on the sound of a common Arabic language.

Technological advancements, mainly in communication technology played an essential role in accelerating the spread of a common imaginary in Arab speaking societies. Egypt’s cultural productions – mainly cinema and music – were and still are the most widespread in the Arab world. The emergence of a pan-Arab popular culture, but also pan-Arab literary currents, was achieved at a time when cinema, radio, and other forms of communication (roads, airports and ports) were being introduced en masse to Arab societies (Hourani 2002, 336-40). Furthermore, Arabic language is the fundamental element in any idea of Arab nationalism. It is through this language that any such narrative has to be articulated and propagated. The emergence of a new form of transnational Arabic during this period is another factor that contributed to the spread of the nationalist narrative. Technological breakthroughs in communication were spreading a new simplified medial Arabic that would emerge as a transnational language adequate to the message of Nasser and his radio broadcast (ibid, 340-2).

Between 1930 and 1950 changes in the social and economic structure of the Arab states led to the emergence of new classes and new notions of belonging, and subsequently created new needs on political, social and discursive levels. In this sense, my aim in this section is to explore different forces that led to a rise of a common Arab consciousness and a notion of Arabism that would take a concrete shape in the discourse of the Egyptian revolution and its Arab-socialist system.

A key force was the rise of a common Arab class consciousness and strong anti-imperialist feelings among the lower and middle classes that would provide a strong vehicle for the message of Arab socialism to spread in urban centers across the Arab world. Prior to the revolution, the breach between the ruling class and the population was burgeoning. The intense and rapid expansion of urban populations was significant in the formation of new political and social trends opposed to the status quo that the ruling classes were aiming to maintain. During this era the economies of the Arab states were growing and with them their dependence on the West. The discovery of oil in the Gulf increased western interests in this region and subsequently western hegemony. Urban societies were subjected to a number of changes and new political ideas were emerging to contest Islam’s place as a common identity. A new class of urban proletariat was emerging, cities were growing, rural immigration was increasing, education was expanding and women were starting to participate in the economy (ibid, 345-79)[x]. Economic growth in the Arab countries depended on aid and investments from industrialized nations. Investments and loans from industrialized states were given with a political agenda especially once the Cold War reached the Middle East. Aid was not only economic but also military. Dependence on the countries which provided aid increased and they remained indebted (ibid, 366, 377-8).

One major change in the Arab socio-economic landscape was the discovery and exploitation of oil in the Gulf States. This had two major effects: transforming these states from poor tribal desert regions into industrialized oil producers which meant a growing need for work force which came mainly from Egypt, Syria and other countries of the Arab world; and transforming these states into a vital strategic target for the industrialized countries (ibid, 378). The discovery of oil drastically changed the geopolitical and strategic value of these states. Thus, as the time of direct colonialism was over, different approaches of control were needed: friendly regimes had to be supported, or put in place by the industrialized states whether European, American or Soviet. The end of direct colonialism was clearly not an end to colonial domination or imperialist hegemony, which made a strong case for anti-imperialist narratives to gain ground in Arab societies[xi].

During these two decades a fast mutation on technological level was visible throughout the Arab world. The Arab nation-states were introducing new techniques of mass-communication triggering transformations on social, economic and cultural levels. These developments reduced distances in the Arab world, allowing a faster and easier spread of cultural goods. Transportation, publishing, and media were the main fields of change. Developments in transportation and air travel made the distances between hitherto remote quarters of the Arab world smaller. Travel from one city, or country to another became more frequent with the further development in road building and railroads. Immigration of workers from Egypt and other Arab countries where workforce was abundant to the Gulf States provided further contact and exchange between Arabs from different states (ibid, 338-9; Sharabi 1966, 13).

Publishing flourished in Cairo and Beirut where intellectual circles gathered thinkers, writers and poets from all Arab states due to the relative political freedom and diversity, as well as the presence of established educational institutions. New means of expression and media provided a space for discussion which united educated Arabs more than ever before (Hourani 2002, 338). With the quick educational revolution a new market of readers was growing in most of the Arab countries providing these publications with a transnational readership of students and literate Arabs (ibid, 392-7). New media was also gaining ground in both entertainment and information. Apart from newspapers which had a growing number of circulation and a more regional appeal, radio and cinema had become by the late 1940’s a popular entertainment accessible for a large part of urban populations (ibid, 393).

Since the 1950’s, transistor receivers were relatively inexpensive, a factor that enabled lower income people to purchase them and have access to radio broadcasting (Boyd 1993, 4). Often, whole villages would have one radio receiver and listening would be a group ceremony (Hourani 2002, 393). The spread of radio among populations of all classes enhanced the social influence of the medium and popular, recognizable voices appeared such as Umm Kulthum, Nasser and Ahmad Said (presenter and manager of Sawt el Arab) (ibid, 393).

In fact, the creation of the Sawt el Arab channel and in more general terms the Egyptian broadcasting system was part of Nasser’s revolutionary project. It was an intrinsic part of the revolution and its exportation to the other Arab states. Nasser envisioned Egypt as playing a central role in the Middle East and the Arab world under his leadership. This is apparent in his book, The Philosophy of the Revolution where he makes hints to his political designs and indications of radio broadcasting services which he would serve political goals (Boyd 1975, 645). Nasser’s awareness of radio’s strategic power was thus reflected by his personal role in launching Sawt el Arab and defining its agenda. The channel succeeded in its goal and quickly became a major medium in the Arab world through which Nasser would disseminate his ideas of Arab unity and incite revolutions outside of Egypt (Dawisha 2005, 147).

The radio also presented new paradigms: simultaneity, entertainment and sensationalism. It was able to transmit Nasser’s speeches with all their emotional connotations and richness simultaneously to the listeners and the crowds; it could unite a transnational public listening to the same voice at the same time while being aware that across the political frontiers many other Arabs were hearing the same voice. Nasser’s speeches became group or radio ceremonies similar to what Katz and Dayan call media events and television ceremonies where viewers are sharing the same live images of an event broadcast on their television screens (Dayan and Katz 1992, 14-17). These were events in which Arabs were able to participate in and consolidate a nationalist sentiment. Radio was an ideal medium; it could bypass the problem of illiteracy and appeal to a wide range of listeners in various cities in the Arab world (Boyd 1993, 28; Boyd 1975, 648).

The efficiency and the importance of the radio in Nasser’s strategy was such that during the 1956 war, the British army attacked Egyptian radio transmitters in the hope of silencing the Voice of the Arabs making way for their station broadcasting from Cyprus to take its place and propose Nasser’s ouster. The bombing was not successful and neither was the Voice of Britain. The Arab staff of the British station resigned once the programming became counter propaganda. This episode gave way for new strategies: the need for more transmitters and decentralization of their locations was now necessary to protect the radio broadcast. At this juncture radio had become a strategic weapon (Boyd 1975, 649)[xii].

In his Cairo Documents, Muhammad Heykal, a prominent Arab journalist and consultant to Nasser, recalled a meeting between the UN Secretary General Hammarskjold and Nasser. The first had asked Nasser: “Can we disarm the radio?” to which Nasser replied: “How can I reach my power base? My power lies in the Arab masses. The only way I can reach my people is by radio. If you ask me for radio disarmament, it means that you are asking me for complete disarmament” (Boyd 1975, 650-1).

Furthermore, apart from the radio, cinema houses were spreading in Arab cities and movie going quickly became accessible to poor urban classes as well as to rural communities. Egypt was by far the largest film producer and Egyptian films were popular in all Arab countries, competing with Hollywood productions. Egyptian films, shown in cinemas in all Arab cities, spread common images about society and national struggle. Simultaneously, these films were spreading a familiarity with Egyptian voices and movie stars, Egyptian colloquial Arabic and Egyptian popular music. As a result, these were becoming a shared Arab culture par excellence (Hourani 2002, 392-3).

These developments in mass-communication contributed to the social mutation in the Arab world. Arabs in different nation-states now had access to a shared world they could move in and a common imagination thanks to books, newspapers and new media (ibid, 338-9). Hourani writes that at this time “there was an increasing mass of material to feed the minds of those who saw the world through the medium of the Arabic language and most of it was material which was common to all Arab countries” (ibid, 392). It would be hard to imagine the emergence of Arab nationalism as a mass movement in the Arab world and its appeal to people in distant quarters of the Arab world without the earlier presence of a common culture, or a common imaginary that was made possible by technological and cultural advancements.

Several currents in literature and popular culture appeared during this period. This resulted in the introduction of a common imaginary and a common cultural heritage for the Arabs in different nation-states. In this sense a common popular culture, which was Egyptian in most cases, became accessible to all Arabs and shared by most of them (Dawisha 2005, 143-4, 148). Moreover, some of the notions of identity and modernization that were articulated and discussed by intellectual currents of the period would reappear in Nasser’s narrative of Arab nationalism. The technological advancements in media and communication made it easier for these literary currents and popular culture to achieve a regional influence and transnational reach[xiii]. The intellectuals were in most cases familiar with both the culture of the colonizer and their own. They were concerned with possibilities of change and reform in the status of their societies and identities. With the emergence of Arab nationalism as a discourse of change that was concerned with social justice and the articulation of a local cultural identity this generation of intellectuals would join the ranks of Nasser’s revolution and provide the intellectual basis for it (Hourani 2002, 395).

Another central aspect in this period was urbanization and the rise of a class of urban proletariat in the larger cities. The rise of an Arab proletariat and the appearance of trade and labor organizations would be essential for the subsequent rise of a class consciousness and of socialist trends among these increasingly numerous groups in most Arab states. A new urban educated class was starting to accept the ideas of Arab nationalism propagated mainly by the Syrian Ba’th party, the first Arab nationalist party to have a social impact in the 1940’s. The rise of local education created a new class of educated urban professionals who had a less westernized social background. It was this class that was oriented towards Arabism and Islam (Sharabi 1966, 13; Dawisha 2005, 124-7). The importance of local education as opposed to the colonial educational systems was to introduce a new individual whose ideas derived from its local Arab roots. The colonial system of education was sustaining an educated class during the colonial period whose ideas are taken from the West, thus creating a colonial, hybrid individual who knows only to assimilate the teachings of the West and once faced with the local culture would find themselves alienated. In a way Arab nationalism was the product of this hybrid class (Hourani 2002, 389-97).

As the Arabic nations had substantial agrarian populations, the peasantry represented a considerable force of support for the revolutionary movements. The intellectual vanguard came from the small bourgeoisie and the professional classes. It was a consequence of the educational development described above and would have a crucial role in rallying the rural populations around the Arab nationalist movement. In fact, these intellectuals were in part rural immigrants to the cities and assumed the role of “translating” the political and ideological foundations of nationalism and socialism to the illiterate peasants and workers in villages as well as in cities. A recurrent theme in Arab engaged cinema and theatre is the character of the young rural immigrant who comes back to his village after he had acquired education in the city to spread the ideas of nationalism and socialism encountered in the city.

The spread of Arab nationalism could not be achieved without a modernization and a popularization of the Arabic language. After all, it was this language that formed the foundations of the emerging Arab identity and the raison d’être of Arab nationalism. As long as it remained secluded within the borders of the educated classes it could not consolidate the masses that every revolution had to address. Arabs in different quarters of the region speak very different forms of colloquial Arabic and often so different that communication is impossible between them without the use of an intermediary form of Arabic. The common Arabic is the literary or classical Arabic, the language of the Quran and written texts, itself inaccessible for illiterates (Sharabi 1966, 4).

Arabic language as such plays a central role in Arab politics as the language of political discourse. As the language of the Quran it carries religious undertones and Islamic imagery (ibid, 93). The language had been going through a process of modernization since the late 19th century with the intellectual movement of Al-Nahda (the Arab renaissance in late 19th century and early 20th) to meet the requirements of modernity, notably in the novel and the press. This simplified version of Arabic (a mixture of classical language and colloquial tones) remains the official language of political discourse (ibid, 93-4). In the first half of the 20th century namely during the 1930’s, Taha Hussein, one of the most important thinkers and writers in the Arab world demonstrated that Arabic “could be used to express all the nuances of a modern mind and sensibility.” Even though Taha Hussein, an Egyptian, was hostile to the idea of an Arab nation and rather emphasized on the distinctiveness of Egypt as an entity, his work on Arabic had an important effect on the later development of it as the language of the modern Arab Nation (Hourani 2002, 341-2). New literary formats like the novel and the journalistic article introduced a simple construction and a more accessible vocabulary. Newspapers, radio and films spread a modern and simplified version of literary Arabic throughout the Arab world. Thanks to the widespread of Egyptian music and films, Egyptian voices and intonations were already familiar everywhere (ibid, 340).

During the revolution in Egypt a ‘medial Arabic’ would rise chiefly with Nasser and Naguib. This language would characterize radio broadcasts and political discourse (an oral combination of a simplified Arabic and spoken colloquial tones and intonations). This language had an unprecedented impact on people “who were addressed for the first time in their own spoken language” (Sharabi 1966, 94), in a simplified discourse which created a close link between them and the leader. Sharabi notes that “the revolution itself brought this new facility and ease to the Arabic language and enabled the rise of a truly mass press and popular literature. […] it removed a profound psychological barrier separating the illiterate masses from the educated classes of society and created on the political plane a new sense of unity and belonging” (ibid, 94).

Nasser himself had a great influence in establishing a new style in political speeches. He had a talent for using the Arabic language effectively and he helped popularize modern Arabic which is widely used in mass media. His live-transmitted public speeches combined elements of Egyptian colloquial, which was already widely understood by Arabs, with classical Arabic (Boyd 1975, 646; Dawisha 2005, 149). As will be examined in Chapter 3, Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s Secretary General, employs a similar style combining literary Arabic and Lebanese colloquial language in his speeches. This oratory skill is a component of Nasser’s charisma. What resulted was a political discourse which could be understood by the illiterate and the educated alike and which as Sharabi notes gave the people a sense of “unprecedented kinship with the new leadership” (Sharabi 1966, 94).

Nasser’s public speeches, his charisma and oratory skills, reached the Arab public on the waves of the Sawt el Arab radio station and became an essential component of his strategy to propagate Arab nationalism. In his speeches Nasser utilized terms and imagery that addressed the concerns and daily experience of the common people. His common use of the word “Karameh” (dignity) is an example. Dawisha writes: “for the millions of common folk in Egypt and the rest of the Arab world who for years had suffered untold indignities at the hands of the colonizers, karameh would find a sure resonance in their hearts” (Dawisha 2005, 149). Nasser would also refer to the great Arab history in order to root the Arab identity in a historical ground. Nasser’s claims were accompanied with practical policies to make his narrative credible. Focusing on education, he would enhance Egypt’s influence by encouraging the export of Egyptian teachers to other Arab countries who would spread the ideals of Arab nationalism (ibid, 150).

Nationalism, colonialism and Islam

Southern Lebanese Borders – Photo by Walid el Houri

Political life and ideas of governance in the Arab world have been influenced by two major forces: Islam on one hand and colonial domination on the other (Sharabi 1966, 15; Hourani 2002, 345-9). Arab nationalism and political Islam both share these influences. It is not the intention of this chapter to map out the development of Islamic political thought and philosophy or the details of the colonial experience, however, it is essential to mention the impact of the colonial experience on the post-colonial political projects that will emerge in the Arab states.

While Islamic political thought had little influence over the nationalist projects that were primarily influenced by the European ideas of modernity, it would appear more clearly in the articulation of the emerging political Islamic groups in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Emerging Islamic movements were preoccupied with different interpretations of the Islamic state. They built on earlier theological work and Islamic political thought as well as the ideas of modernity in order to provide state building projects that met the requirements of the present while being faithful to Islam. The Iranian Revolution and Khomeini’s theory of the “rule of the Jurist” in the Islamic Republic and Sayyid Qutb’s Muslim Brotherhood are prime examples.

The colonial experience had an influence on the development of both secular Arab nationalism and political Islam. Colonialism was linked to the establishment of a new political system of parliamentary democracy. Under French or British rule, parliamentary life produced a strong sense of disillusionment for the Arab intellectuals and common people alike. Local governments were in all cases composed of the corrupt ruling elites who succeeded in gaining the acceptance of the colonizers by acting as their local agents against popular will. The failure of colonial parliamentary democracy in the Arab countries was attributed not only to its application by the dominant power but to the system itself. It came to be associated with corruption and the plundering of local resources by ruling elites and foreign occupiers, foreign interference and exploitation (Sharabi 1966, 57-8). Sharabi puts forth three factors that contributed to the failure of political democracy in the Arab world and its transformation into a synonym of corruption and the domination of foreign interests in the minds of many Arabs.

The first reason was “the continued existence of foreign domination during the delicate phase in which parliamentary institutions were being established.”

The second was the fact that “the monopoly of power” remained in the hands of “a privileged class.”

The third was “the exclusion from political responsibility of the younger generation, particularly as it was represented by the doctrinal parties of the 1930’s and 1940’s” most of which were nationalist or socialist (ibid, 56-7).

Similarly, Hourani claims that the sought independence in most of the countries of the Middle East resulted from “manipulation of political forces.” Ruling families and educated elites immediately came to power through their “social position and political skill which had been needed during the period of transfer of power.” However, these groups failed to get any popular support or to create a state in the full sense of the term. The new/old ruling classes did not, according to Hourani, “speak the same political language as those whom they claimed to represent” nor did they come from a similar social background. They were mainly preoccupied in preserving their own social positions rather than developing the country. This opened the way for revolutionary movements which would articulate the growing needs of their societies by calling for three important demands: strong national identity, social justice and religious revival. Such movements varied ideologically from the Muslim Brotherhood, Arab nationalism, communism or socialism (Hourani 2002, 403).

The revolutionary movements in all their forms (such as Ba’th, Nasserism, Syrian Nationalism, Muslim Brotherhood) were addressing the “popular masses” (Al-jamahir) which were composed of the peasants and the workers – the proletariat (Sharabi 1966, 84). As I will address in the next section these would be the target of political Muslim groups that would emerge on the ruins of Arab nationalism. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, Nasser’s narrative of Arab nationalism was successful in gathering these “popular masses” in different Arab states around an idea of Arab socialism and was more successful than any other revolutionary movement of its time. In fact some of these movements like the Ba’th will seek to ally themselves with Nasser to increase their popular support and sustain their political power (Dawisha 2005, 155-6). The Nasserist narrative thus hegemonized three major demands into one single discourse of Arab socialism: anti-colonialism/anti-imperialism,social justice/socialism and Arab unity.

With the rise of the revolutionary discourse appeared a deep division among two camps in the Arab world: the revolutionary states (Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Algeria) and the monarchical ones (Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Morocco, and Libya) and in between were states such as Lebanon and Tunisia who were liable to influence from both sides of the political divide. In Nasser’s discourse “liberation” acquired a new meaning; it was no longer the liberation from foreign rule but from the corrupt ruling regimes as well. Nasser’s rhetoric placed “revolution” against “reaction” (Sharabi 1966, 11-2). Sharabi writes: “Al Thawriyah [revolutionary ideology] is not just a political revolution, but represents a comprehensive attitude toward social and economic life, including new values and criteria of thought” (ibid, 82). The revolutionary movement was in this sense reflecting a new dominant discursive force, which would re-define values and truths in the Arab societies, revolutionary and non-revolutionary alike. As I will expose throughout this project, this articulation of resistance is also present in Hezbollah’s discourse where a chain of equivalence is also made between political and economic liberation and the ideological stance towards imperialism.

In conclusion, the failure of liberal democracy under colonial rule in the Arab countries resulted in a social injustice that the revolutionary movements that emerged sought to oppose. This movement, as Sharabi notes, resembled in many respects “the rebellion of the ideological and socialist revolutionaries in early 19th century Europe”. The new system of values believed that oppression in the Arab states is “the perpetuation of the social and economic systems created under European domination and represents an extension of European capitalist exploitation”. Independence after the end of the mandates becomes “the economic and social liberation of the masses and as a second step, their integration into the political order of society” (ibid, 83).

The opposition between the revolutionary and monarchical camps, became one of the central aspects of the discourse of the revolutionary ideology of Nasser: the dichotomy between “progressive revolutionary” (taqadoumya el thawrya), and the “reactionary opportunistic” (raj’ya el intihazya) supported by “imperialism and colonialism“. This radical opposition between the two was based on the revolution’s expanding aspect to the “non-liberated” countries. “The mission of the revolutionary states” was after all to export the revolution and fight imperialism wherever it might appear (ibid, 86).

Outside of Egypt, Nasserism, was gaining ground partly because of the personality of Nasser and because of his successes namely the 1956 war, the High Dam, social reform and his defense of the Palestinian cause[xiv]. These achievements provided a sense of hope and empowerment to Arabs everywhere. They were delivered to the Arabs by the transnational press and radio which appealed to “Al jamahir” which ironically means both the masses and the audiences (Hourani 2002, 407-9; Dawisha 2005, 147-8). While the expanding audience of Nasser “deepened conflicts between Arab governments” – which at present are divided between the “moderate states” and the “axis of refusal” – Nasserism “remained a potent symbol of unity and revolution” (Hourani 2002, 407); in this sense it created an imaginary self for Arab peoples to identify with.

While Arab nationalism was gaining ground in many quarters of the Arab world, in many countries it was still the idea of Islamic brotherhood that remained at the forefront of forces of change. Islamic brotherhood with its pan-Islamic scope was a natural opponent of Arab nationalism. These two articulations of political identity have been in a constant competition and conflict (the hostility between the Muslim brotherhood and Nasser is one major example, but also in Syria between the Muslim brotherhood and the Ba’th) (Sharabi 1966, 6; Dawisha 2005, 188-9; Hourani 2002, 398-400).

Sharabi argues that the revolutionary ideology did not fully succeed in giving legitimacy to the regimes which represented it in the revolutionary states and ultimately failed to achieve its ideals of unity and social justice. Nonetheless even though the revolutionary ideology did not succeed in uniting the Arab world, it did succeed “in transforming the political environment” and in creating a new notion of identity – being Arab – whose impact is still felt to a certain degree today (Sharabi 1966, 87-91; Dawisha 2005, 153).

In the next sections, I will analyze the impact of the failure of Arab nationalism after the 1967 defeat of Nasser – “al Naksa” (the setback) – on the emergence of political Islam. This episode is essential for understanding the conditions of emergence of Hezbollah out of the growing Islamic revolutionary movements that appeared in the 1970’s and for understanding the discursive strategies of Hezbollah and the meanings and narratives that will be analyzed in the following chapters.

“Islam is the solution”

In his book La Question Religieuse au XXIe Siecle, Georges Corm analyzes the conditions that led to the return of the religious to the forefront of the political sphere around the world. Corm argues that In the last three decades more and more people identify with and are being identified by their religious belonging (Corm 2006, 5). Religion has come to stand for more than personal belief and has become a political identity. Muslims are no longer only those who practice Islam, they are treated as an ethnic group, or a ‘culture’ – and as a political group. One can thus be identified as a Muslim or even identify as a Muslim while being an atheist for instance[vx].

In fact during the 16 years of Nasser’s rule (1954-1970), Arab nationalism while it failed to unite the Arab world under one nation, succeeded in marginalizing all other ideologies (Choueiri 2005, 308). In other words, even though Nasser’s project of a united Arab nation failed and the experience turned into an authoritarian single party rule, the legacy of Arab nationalism inasmuch as it formulated a sense of being Arab became and remains influential until today.

The analysis of nationalism in the Arab world is often described in terms of a movement that neutralized the role of religion, or as the outcome of the decline in the influence of the religious institutions on a population that is becoming more educated and “modern” (ibid, 294). The secular nature of the hegemonic experience of Arab nationalism, while being opposed to the Islamic tendencies that were contesting the political field at the time (The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt for instance), did not mean that religion was uprooted from the Arab societies. In fact Gilles Kepel writes that: “theoreticians of ‘developmentalism’ have tended to equate modernization with secularization. But nowhere in the Muslim world of the late 1960’s did religion vanish from popular culture, social life, or day-to-day politics. Islam was merely handled in different ways by different regimes and was combined with nationalism in ways that varied according to the social class of those who had seized power at the moment of independence” (Kepel 2006, 47). In fact, as Kepel recounts, even during the heyday of secular nationalism, education in Egypt, Syria and Iraq stressed on the socialist character of Islam. Official educational material claimed that if “properly understood” Islam would promote socialism (ibid, 47).

Choueiri proposes four common points between religion and nationalism: they are both “spontaneous or involuntary responses to sociological factors and psychological dilemmas“; ” universal, in the sense that all societies have had to adopt one or the other in their historical development“; “sublimate ‘male dominance’”; and “are emotionally charged and often shot through with the energy of constant endeavour and self-sacrifice. The concept and practice of martyrdom often straddle their inner dynamics” (Choueiri 2005, 295).

Choueiri goes on to suggest an understanding of these identities as based on an experience of loss – a lack in the Lacanian vocabulary (ibid, 295). Such an experience of loss allows religion or nationalism to provide a discourse that would provide the promise of restoring the previous state of fullness. Nonetheless, Choueiri argues, religion and nationalism present essential differences. The main difference pertains to geographical limits. While nationalism is founded on a clear and defined geographical border that the nationalist discourse will endow with “a cherished national legacy, political religion abhors borders, decries national identification and tries to soar above human ties centered on defined territories” (ibid, 296).

Choueiri identifies another difference between the two political projects in the tendency of religious discourse to demarcate clear distinctions between “believers and non-believers, men and women, God and the community of the select, the chosen and the true representatives of the divine will as opposed to a collection of errant groups of people” (ibid, 296). However, I would argue that this, rather than being a difference, is more of a similarity between the two inasmuch as nationalist discourses tend to equally classify the population into those who are faithful to the nation and those – “traitors” – who act against the national will.

Thus, religion has always played a part in the national struggles in the Middle East – albeit superseded by the hegemonic status of secular Arab nationalism during a specific period. Watts, on the other hand, argues that the experience of secular nationalism in Turkey, Egypt or Iran, “exposed the superficial rooting that secular nationalism had developed within Muslim civil society” (Watts 2007, 194). In fact, secularism was seen by religious groups as an extension of the colonial project and after the failure of Nasser, religious movements “demonstrated that they have now gained ground in terms of populist politics at the expense of those that champion secular nationalist ideologies” (Choueiri 2005, 459).

In this framework Watts argues that Islamic movements have been the most active on the political and social levels in filling the gap left by Arab nationalism. In other words, Islamic movements have proved to be very active and efficient in their presence and organization of civil society and providing alternative institutions to the state that support the masses of poor marginalized people (Watts 2007, 192).

According to Milton-Edwards, “The resurgence and revival of faith in the 1970’s has traditionally been tied to explanations of the ‘watershed defeat’ of the Arabs against Israel in the Six Day War of 1967 and the emergence of a ‘crisis of identity’ in Muslim majority states in the region” (Choueiri 2005, 455). The defeat of 1967 and Nasser’s resignation almost immediately after it (which was later retracted) was, in the words of Kepel “a major symbolic rupture” (Kepel 2006, 63). Rather than defeating Israel as repeatedly promised by Nasser, in 1967 the Arab armies were the ones to be humiliated and more Arab land was lost. With this material and symbolic loss, the aura of Nasser and his Arab nationalism collapsed, leaving the terrain ripe for the Islamist movements (ibid, 63). Arabs and Muslims were quickly disenchanted with the promises of Arab nationalism which led to increasing “political activism in the name of Islam” (Choueiri 2005, 456).

Indeed the defeat of 1967 caused a great “disturbance of spirits” and questions about whether there was a moral cause for it erupted (Hourani 2002, 442; Choueiri 2005, 455). The defeat, it was later argued by Islamists, was precisely the result of a lack of faith in the secular regime of Nasser. Kepel writes that “conservative Saudis would call 1967 a form of divine punishment for forgetting religion. They would contrast that war, in which Egyptian soldiers went into battle shouting “Land! Sea! Air!” with the struggle of 1973, in which the same soldiers cried “Allah Akhbar!” and were consequently more successful” (Kepel 2006, 63).

The defeat of 1967 changed the balance of power between the ruling regimes and Islamist movements. While Nasser’s nationalism was in power, Islam was kept away from the political field even though it remained an essential aspect of people’s day to day lives and personal identities. Once nationalism was defeated, Islamic groups were able to enter the political field and challenge the weakened states. Furthermore, the disenchantment of people allowed these groups to gather more recruits than at any time during the reign of the nationalists (Dawisha 2005, 278). At that moment the slogan of Muslim groups became “al-Islam huwa al-hal, ‘the only solution is Islam’, and they could have added, the only permissible identity was Islamic” (ibid, 279). By the mid 1980’s, Arab nationalism had been long gone between the strengthening State-nationalisms in all Arab states and the predominance of Islamic opposition to the Arab regimes from Syria, Iraq, Egypt and Algeria. Indeed, “the rejuvenation of Islam as a radical political alternative robbed nationalism of whatever chance of recovery it might have entertained after 1967” (ibid, 296-7).

From Arabism to Islam

It is true that Arab nationalism as a political project of uniting Arab states into one nation had died, however, Arabism inasmuch as it is a cultural proximity established between the different Arabic speaking peoples during the decades of Nasser’s message kept on living. This meant that citizens of different Arab states were expected to voice their opinion about the conduct of regimes anywhere in the Arab world. Arab regimes were aware that their policies spilled over the linguistic borders even if these borders became more significant to national identities than ever before. This tendency Dawisha would call Arabism as opposed to Arab nationalism (Dawisha 2005, 252-4). This Arab public sphere would be the field where emerging Islamic discourses operated, and, as we will see later in this chapter, in Hezbollah’s case, the movement adopted a discourse that establishes the interests of the Arab nation as identical to those of the Muslim one especially in reference to the Palestinian cause and the struggle against imperialism.

Islam however had become a major factor of legitimacy for any regime. By the late 1970’s and early 1980’s “any Arab government which wished to survive had to be able to claim legitimacy in terms of three political languages – those of nationalism, social justice and Islam” (Hourani 2002, 451). Thus, secular and non secular regimes alike had to start using Islam in varying ways (as a cultural heritage or as a religious doctrine) to justify their rule and in self-defense against growing Islamist groups who themselves were successful in articulating a political discourse that combines the three elements (ibid, 452-3). “In the 1980’s and 1990’s, radical Islam had become for the Arab regimes what Arab nationalism was in the 1950’s and 1960’s” (Dawisha 2005, 277)[xvi].

While the 1967 defeat had a crucial effect on the rise of Islam as an alternative discourse, it was not the only factor in this resurgence. Islamists argued that the post-colonial secular nationalist experience was “untrue to Islam and lacking ‘authenticity’” (Fuller 2004, 69). In fact, even the most anti-imperialist regimes of the post-colonial period – Nasser being a characteristic example – were based on a “Western model of state building” (ibid, 69) and were soon caught in the whirlpool of structural problems left by the colonial years and became mere authoritarian regimes imposing policies from the top down (Turkey, Iran and Egypt are the typical examples).

Once these authoritarian nationalist regimes failed in the face of Israel and the Imperialist other, Islamists were quick to claim both authenticity and a hostility both to the Western and the Communist other for that matter. The Islamists were naturally opposed to the ruling elite which in most cases was either secular or in other cases allied with the West. While they did speak for the poorer segments of society, Islamists did not adopt class based discourses, rather – as was the case in other parts of the world where a religious revival was succeeding to the post-colonial secularist regimes (Fuller offers India, Israel, Sri Lanka, and Latin America as other examples in this case) – Islamists adopted a discourse that was directed against the established order (ibid, 70).

The language of Islam was able to mobilize and appeal to Arab people in a way that Arab nationalism had succeeded a decade before. Hourani writes that “Islam could provide an effective language of opposition: to western power and influence, and those who could be accused of being subservient to them; to governments regarded as corrupt and ineffective, the instruments of private interests, or devoid of morality; and to a society which seemed to have lost its unity with its moral principles and direction” (Hourani 2002, 452). Islamic groups were taking advantage of two important factors that ensued from the defeat of nationalism: on the one hand the uncertainty of the ruling forces after the 1967 defeat and the disappointment among both intellectuals and masses. Thus, Kepel writes, “conservative governments, on the Saudi model, encouraged Islamism as a counterweight to the Marxists on university campuses, whom they feared. And some of the young leftist intellectuals, as they took stock of their failure to impress the masses, began to convert to Islamism because it seemed a more genuine discourse” (Kepel 2006, 64).

What gave Islamists and especially the militant movements among them, another ideological impetus was the success of the Iranian Revolution in 1979 (Choueiri 2005, 457; Kepel 2006, 61). The revolution provided the model for Islamists whether Sunni or Shiite, in order to establish a modern Islamic state (Dawisha 2005, 278). Watts states that “Iran provided an imagined community of immeasurable power for all the Muslims that resonated across sectarian and political lines” (Watts 2007, 192). The years that followed the revolution were marked by unrest in many parts of the Arab world, all of which were instigated by Islamist movements: Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Algeria, Tunisia, Bahrain in addition to Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Morocco (Dawisha 2005, 279).

While much of the Islamist movements of today are – at least in words – revolutionary and anti-imperialist, this cannot be said about the Islamists of the 1970’s. Kepel writes that “The Islamic upsurge of the 1970’s was not merely a revolutionary, anti-imperialist movement that roused the impoverished masses by the skillful use of religious slogans, as in Iran. Nor was it simply an anti-communist alliance forged by the Americans and the Saudis. To measure its full impact we need to identify its many dimensions and investigate the different periods of gestation, the networks, the lines of communication, the tendencies and ideas that composed it, with the context of the demographic, cultural, economic, and social realities of the decade” (Kepel 2006, 62). In the next section I will attempt to provide an overview of these dimensions before providing a more specific context that pertains to the emergence of Hezbollah as a Shiite religious movement.

Slums and globalization

The rise of political Islam has its roots in many different grounds. Apart from the crisis of identity, the trauma of the 1967 defeat of Arab nationalism and the failure of the secular nationalist state model, the economical and technological transformations in the Arab world were of equal importance. Watts argues that the rise of political Islam must be read along the lines of the failure of the Arab nationalist model and the “poisonous political-economic conjuncture (oil, primitive accumulation, and cold war geopolitics are its coordinates)” (Watts 2007, 193).

Indeed with the 1967 defeat, the “crashing waves of petro-capitalism, neoliberal austerity, and recession” the effects of the nationalist experience led the way to a collapsing of the link between the “political classes and the urban poor” (ibid, 194). Social and economic crisis were essential to the emergence of new means of articulating demands of new groups of people, most notably the urban poor. These were the first target of Islamist movements in addition to a religious bourgeoisie who had different interests and expectations but both agreed on an opposition to the current ruling elite (Kepel 2006, 67). Thus, Islamist movements took two opposing forms: on one hand a conservative reactionary one supported by Saudi Arabia and the US against communism and socialist reforms and whose aims were not the empowerment of the urban poor. On the other hand, a revolutionary one supported by leftist movements and the USSR as an anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist trend, namely the early days of the Iranian revolution (ibid, 68).

The 1970’s and 1980’s witnessed some of the most important political events for the emergence of political Islam in its present form. The rising oil prices made Saudi Arabia one of the biggest regional powers after the 1973 war and the death of Nasser in 1970. The Iranian revolution had a great influence on the existing Muslim movements in the Arab world. Furthermore, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the American-Saudi support of fundamentalist Islamic resistance against the Soviets (today’s Al Qaeda) and the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) were major events that reshuffled the geopolitical field to the advantage of the Islamists (Choueiri 2005, 311; Ali 2002).

Like many others, Watts relates the ascension of political Islam to the growing slums around the big cities in the developing Muslim world (Kepel 2006; Fuller 2004; Choueiri 2005; Watts 2007; Hourani 2002). After all, Watts argues, “Islamic cities have always been the theatres in which the complex dialectics of ruler and ruled, man and woman, and space and identity have been performed” (Watts 2007, 193). The population growth in the Muslim world presented “a demographic change of spectacular proportions” (Kepel 2006, 66). By the mid-1970’s, Kepel writes that those under 24 years old “represented over 60 percent of the total population” (ibid, 66). The populations were growing increasingly urban and the movement towards the cities and their outskirts led to the growth of massive urban slums.

While the living conditions in these slums deteriorated, education accelerated and the proportion of literate and university students of both genders was growing with Arabic as the language of education (Hourani 2002, 424). The developments in education meant that more and more of these poor urbanites had access to “newspapers and books but also great expectations of upward mobility” (Kepel 2006, 66). The upward mobility did not happen, instead unemployment, frustration and anger against the ruling elites meant that “social and political discontent was most commonly expressed in the cultural sphere, through rejection of the nationalist ideologies of the ruling cliques in favor of Islamist ideology. This process began on the once left-leaning university campuses which were now, in the early 1970’s, controlled by Islamist movements” (ibid, 66).

According to Hourani, two factors led to Islam having a greater role within the political discourse in the 1980’s: “on the one hand, there was the vast and rapid extension of the area of political involvement, because of the growth of population and of cities, and the extension of the mass media. The rural migrants into the cities brought their own political culture and language with them. There had been an urbanization of the migrants, but there was also a ‘ruralization’ of the cities. […] The sense of alienation [of these migrants] could be counterbalanced by that of belonging to a universal community of Islam. […] those who wished to arouse them to action had to use the same language” (Hourani 2002, 452). From the deteriorating living conditions of the growing urban population, to the increasing education and the new means of communication and expression grew a new group of people who were articulate and able to express themselves in a language different from that of the traditional educated elite (ibid, 442-3). Thus, a growing discussion about the role of religion in the organization of society appeared from the slums and new voices emerged claiming the need for a religious thought that could establish a basis for a revolutionary party (ibid, 443-5).

Most of the Arab states were authoritarian regimes where the division of wealth was radically uneven. In other words, these were states that had failed on both economic and political levels leading people to demand more democratic forms of representation and an economic structure that would provide a solution to the growing unemployment and poverty (Fuller 2004, 77). A constellation of demands from the economic to the political were to be articulated around a chain of equivalence with Islam at its center. As Fuller argues, such states were “adept at developing empty forms of quasi-democratic governance, basically institutional shells that continue to deny political power to all but the elite.” For Fuller, this condition did nothing but intensify the sense of frustration that would be picked up by Islamic groups who would provide both a means of voicing this frustration and palpable social and economic support networks to alleviate the suffering of the poor urban populations. Furthermore, since most of these regimes were supported by the United States (Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, Morocco, Saudi Arabia) it was only logical for the opposing Islamic groups to adopt an anti-Western stance (ibid, 69). It is therefore no surprise that in most Arab countries the Islamists have become the strongest forces of democratic opposition to established authoritarian regimes (ibid, 77).

Another important factor of the emergence of political Islamic groups was the weakening of the state structure. In this framework Fuller writes that “as the state’s sovereignty is weakened, it comes under assault across much of the Third World: from above by globalization, international organizations, the spread of new global norms, global interdependency, ease of transportation reducing isolation, loss of control over internal communications due to satellite communications and the Internet; and from below by rising regionalism, ethnicity, criminal organizations, and the breakdown of state control and authority at local levels” (ibid, 76).

Islamic movements, as I have argued before, are universalist in nature, as opposed to the geographically delimited nationalisms. And while Islamist movements are generally anti-globalist in the vague sense of the word, they are both a reaction to and a product of the processes of globalization. This is not specific to Islam but as Fuller argues, pertains to the increasing role of religions in general: “the combination of the disruptive effects of globalization and the desire to establish moral foundations for authority have contributed to the increasing role of religion in politics. Islam is just one of many religions to engage in political and social involvement” (ibid, 78).

The destructive effect of globalization on the economies of many developing countries is clearly seen in the unbalanced development between Arab countries and within them. The growth of slums around the big cities is one example. Globalization has come to stand for an “essentially Western project containing its own ideology and agenda, whose challenge generates new threats, dangers, discontents, and reactions. Globalization to many is simply a new form of Western or American hegemony in a massive economic, political, and cultural package of questionable benefit” (ibid, 73). This leads to the emergence of various articulations of anti-globalist movements that are essentially anti-American. In the Muslim world, as this chapter argues, Islamism has come to stand for this position, however, this is nothing particular to the Muslim world but seems to be shared by most developing countries with movements adopting different articulations and ideologies in different places. Going back to Fuller, “Islam need not be anti-Western or anti global by definition, but it functions as guardian and repository of cultural tradition that emerges from Islamic faith, culture, and tradition. The voices raised against the negative impact that globalization and its assumptions may inflict are not only Muslim” (ibid, 73).

This attitude against, or critical of, globalization and its negative effects is one that is shared by Islamists, nationalists, leftists, and other political groups. They perceive globalization as a cultural attack on local traditions with the increasing influence of Western or American culture. The process of globalization is seen as a threat to the sovereignty of states and the economic interests of the marginalized classes (ibid, 74).

The effects of globalization are paradoxical. On the one hand it allows for connections to emerge across boundaries, thus extending interaction between identities and groups. Transnational Islam and Islamic movements are good examples of such a globalization of identity. Globalization also prompts local reactions of self protection by emphasizing particularity and local identities. Islam inasmuch as it becomes a reaction to the “westernization” of local culture is indicative of this as well. In this sense, it is precisely globalization and its discontents that will allow a movement such as Hezbollah to extend its discourse to many international leftist groups as we will see later in this chapter. As Fuller writes “we cannot all be simply ‘global citizens’; cultural homogenization does not furnish warm and fuzzy feelings of belonging. The more our identities are exposed to powerful international influences, the more we seek comfort and meaning in our local culture, mother tongue, customs, food, clothing, and identity as well. When globalization is seen as foreign and threatening (witness popular early American derision at the idea of Japanese car imports) local identities quickly rise to the defense. Islam is one such identity. Islam particularly strengthens identity when arrayed against non-Muslim power” (ibid, 75).

While the effects of globalization engendered an impoverished mass of Muslims, the oil boom of the 1970’s established Saudi Arabia as a major force in the region with the availability of funds that would be used to sponsor Islamic groups to serve the interests of the kingdom and its American ally. Saudi Arabia was already engaged in a common war against communism and socialism with the US since the times of Nasser (Kepel 2006, 51-2) and after the Iranian Revolution petro-dollars flowed in order to sponsor a Wahhabi form of Islam that would fight the Communists (most notably in Afghanistan) and provide a Sunni counter force to Iranian style Shiite Islamism in the region. The growing Wahhabi sponsored Islamism was soon to prove uncontrollable when Saddam Hussein denounced the alliance between Saudi monarchy and the West during the Gulf war (Kepel 2006, 73).

It was not only the sponsoring of Islamist movements outside of Saudi Arabia that was a consequence of the oil boom. The growing immigration from Arab and Muslim countries towards the oil rich Gulf where work and money were plenty (Watts 2007, 195; Hourani 2002, 425) meant that for many of the immigrants who amassed fortune in the Gulf “social ascent went hand in hand with an intensification of religious practice” (Kepel 2006, 71). While the immigration of Egyptians to the Gulf was not a new phenomenon, it should be noted that before 1967, this was largely focused on educated young individuals. After 1967, this was a “mass migration of workers at every level of skill” (Hourani 2002, 425-6). These workers were much more susceptible to ideological influence and what was before a migration of teachers to spread Arab nationalism in the Gulf became a reversed movement.

A final factor essential to the emergence of political Islam as a hegemonic force pertains to the development in media and communication technology. As I have argued earlier in this paper, radio played a central role in propagating Arab nationalism, it would be the new electronic media (audio and VHS tapes), satellite television and later the internet that would provide the communicative tools for the propagation of political Islamic discourses. A new medium, television, was by the early 1970’s part of most Arab households and became “scarcely less important than the cooker and the refrigerator” (ibid, 425).

Watts argues that in order to account for the success of revolutionary Islam, it is necessary to look at three conditions of possibility that “lend it its almost unprecedented anti-imperialist powers.” These conditions are: “the virtual, the incendiary, and the spectacular” (Watts 2007, 188). The virtual relates to the emergence of new media technologies (satellite TV, newspapers distributed free on the internet, chat rooms, and text messaging in addition to the traffic of CDs and DVDs which can “circumvent state censorship”. This is what Watts would call a “mediatic architecture capable of sustaining a transnational Arab public sphere” and help form what he calls the “virtual Umma” (ibid, 189). The growing sense of a shared Islamic community was thus nourished by shared images of suffering Muslim peoples. Regional and global media allowed “the creation of a profound sense of collective suffering” that is propagated by images of dead Muslims from Palestine, to Iraq to Afghanistan (ibid, 189). The incendiary effect of these images is central to the powers of Islamic movements to mobilize people who are emotionally affected by these images. Furthermore, Islamic movements were not only extremely efficient in the spectacular use of images of suffering but also and most importantly in the use of images of violence perpetrated against the enemy which both adds to the incendiary nature of the message and demonstrates the ability of these groups to challenge their enemies (ibid, 191).

The ability to efficiently use media technologies by Islamic groups has been one of the major factors in their growing influence. Whether it is the violent sectarian discourse of Al Qaeda-like groups who promote a discourse of violence against anyone who does not conform to their interpretation of the faith, or the political mobilization and recruitment discourse of groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt whose project is of a political nature in opposition to the ruling dictatorship, or the resistance message of Hezbollah in Lebanon which aims at addressing a more balanced discourse of opposition to occupation and Western involvement in the region, these groups have all demonstrated a significant ability to use new media technologies in ways to advance their claims and articulate their different political discourses.

Having described some of the most important factors in the genesis of political Islam in its general forms I will suggest in the next section a context to the emergence of Hezbollah as a particular case within the larger trend of political Islamism. Hezbollah’s particularity stems from several factors: first its religious identity being Shiite rather than Sunni as is the case for the vast majority of Arab Islamic groups; second its emergence in the Lebanese context where the demographic and political reality of the country where Christians represent one essential community in both numbers and political power has pushed the movement to adopt a distinctive discourse when it comes to dealing with religious difference and state building; third its emergence as a military movement fighting the Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon which established the movement as primarily a military one that had to later establish itself as a political party as well; fourth the emergence of the movement out of an environment where leftist activism was predominant. Thus, in order to account for the discursive strategies and the development of Hezbollah’s political discourse and identity it is important to first investigate the conditions of emergence of the movement out of a specifically Shiite and Lebanese condition.

The emergence of Hezbollah

The emergence of Hezbollah can be traced to two essential transformations that occurred during the decades following the failure of the Arab nationalist movement. On the one hand, the emergence of Islam as a new hegemonic identity in the Arab world as discussed in the previous section and on the other, the developments that took place within the Shiite faith in Lebanon and Iran[xvii]. These two transformations were the result of political and economic changes, exposed in the previous section that redrew the demographic map of the Arab world and the Middle East.

Historically, the Shiites have always been dominated if not often oppressed by the Sunni political power in the Arab world. For this reason, the Shiite narrative of history is imbued with a sense of victimization and an experience of oppression and varying degrees of acquiescence to, or revolt against oppression (Nasr 2006, 90-91). While it is true that Arab nationalism was articulated as a secular Arab discourse, Nasr argues that for many Shiite Arabs the experience of Arab nationalist governments was one of being ruled by “the same Sunni elites – landowners, tribal elders, top soldiers, and senior bureaucrats” (ibid, 90). Nasr writes that “Arab nationalism, which defined national and regional identity for most of the post-independence period, is at its heart a Sunni phenomenon – although many of the thinkers who gave shape to the idea, and especially its most virulent expression, Ba’thism, were Christian” (ibid, 91).

Nasser’s discourse presented a narrative of a lost Arab glory that must be regained through the defeat of imperialism and the residues of colonial power. This particularly referred to Israel, western interests as well as the corrupt monarchies and regimes friendly to the West still ruling some of the Arab countries especially in the Gulf. The image of this golden Arab past, which is essential to any national formation, was criticized by Nasr as being associated to a Sunni past. Nasr argues that Arab nationalism “inherits the mantle of the Umayyad and Abbasid empires and the Ayubid and Mamluk monarchies – the historical expressions of Muslim and Arab power. Arab nationalism’s promise of triumph and glory evoked memories of medieval Islamic power and drew on that legacy to rally the masses to its cause. The flag-bearer states of Arab nationalism – Egypt, Syria, and Iraq – had all been seats of Sunni power” (ibid, 91).

While many Shiites were indeed drawn by Nasser’s discourse, they remained essentially outside of the ruling elite. In Lebanon, Nasser’s discourse proved to be very attractive to the Shiites. As Shaery-Eisenlohr argues “Lebanese Shi‘ites were among the most committed supporters of Nasser, the political mood among Shi‘ites in that period was [secular] nationalist, nationalist, nationalist ( qawmi, qawmi, qawmi ), in all its forms” (qtd. in Shaery-Eisenlohr 2008, 59).