The new media scene in Turkey can be viewed parallel to the establishment of Visual Communication Design (VCD) departments at universities, which goes back to the end of the 1990s. In 1996 private universities founded earliest VCD departments. Yıldız Technical University is the first state university that started such a program, as well as the first master and doctoral degree program in the field. A pioneer in this field, Bilgi University’s VCD department started organizing annual student work exhibits in 2001. These exhibits created a broader awareness of digital technologies. The opening of VCD departments in public and private universities has led to an increased interest in screen based digital media in the last decade. At present there are roughly 170 universities in Turkey, about 45 of them in İstanbul and many of them have a VCD or similar program.

The new media scene in Turkey can be viewed parallel to the establishment of Visual Communication Design (VCD) departments at universities, which goes back to the end of the 1990s. In 1996 private universities founded earliest VCD departments. Yıldız Technical University is the first state university that started such a program, as well as the first master and doctoral degree program in the field. A pioneer in this field, Bilgi University’s VCD department started organizing annual student work exhibits in 2001. These exhibits created a broader awareness of digital technologies. The opening of VCD departments in public and private universities has led to an increased interest in screen based digital media in the last decade. At present there are roughly 170 universities in Turkey, about 45 of them in İstanbul and many of them have a VCD or similar program.

There is not (yet) a department or program solely dedicated to new media in any art faculty of any Turkish university. For the most part, art education still follows a conventional art educational practice, although there seems to be a gradual shift towards conceptual artworks created with different media – even within more conservative institutions such as the Faculty of Fine Arts at Mimar Sinan and Marmara University.

Screen-based interaction has been in the curriculums of all programs from the beginning. But the first course to go beyond screen-based interaction and towards spatial and tangible interfaces in terms of design and art, was offered only recently in 2005 at Bilgi University – and it was actually by me. (I still continue to teach this course at Sabancı University). In 2005, Elif Ayiter and Selim Balcısoy started a multi-disciplinary course at Sabancı University. This course focused on the collaborative work of design and engineering students. Koray Tahiroğlu, a musician who was educated abroad, started similar courses in the Music Department at Bilgi University. In 2008 the students presented their interactive compositions in a club. This was the first event of its kind in Turkey.

While there are several – mostly individual – attempts to develop new media art education, there is still no program that focuses exclusively on new media design and art practice. Some students have created extraordinary new media works. Until recently art programs have primarly considered digital technologies as tools instead of considering them as an artistic medium. New media art did not become mainstream, even among the young generation. It is not a coincidence that almost all (of the few) internationally acclaimed Turkish new media artists continued or completed their education abroad.

Istanbul Technical University, the oldest and one of the most respected technical schools of Turkey, started a masters degree program entitled Information Technologies in Design in 2005. The program could have been very successful considering the experience gained in the field at that time and the initiators’ new perspective on it. Unfortunately it was not able to survive because of bureaucratic complications.

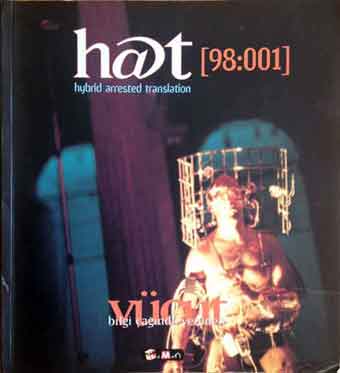

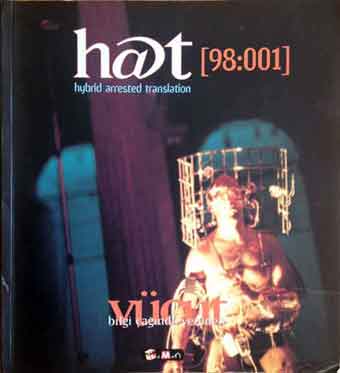

figure# HAT, the first magazine focused on art and new technologies

A new generation of young academics is beginning to emerge. Many universities have created space for new media in their curriculums. Some have even started programs called “new media” which are actually journalism programs, not design or art programs. Therefore VCD programs or departments are still the only creative resources for new media art and design in Turkey. This field is still waiting for dedicated programs.

The earliest attempt to create a platform for new media in Turkey was a media art and theory magazine called HAT (Hybrid Arrested Translation). Only one issue was published in 1998. Fatih Aydoğdu was the editor and initiator of the magazine. In its first and only issue, HAT focused on the “body in the information age”, with texts from Paul Virilio, Vilem Flusser, Arthur Kroker, Hans Moravec and artists like Stelarc, Orlan, Aziz + Coucher.

In 2002, NOMAD was founded as an independent group and officially registered as an “association” in 2006. NOMAD, in their own words, aims to produce and experiment with new patterns in the digital art sphere by using the lenses of various other disciplines. Başak Şenova, Emre Erkal and Erhan Muratoğlu were the initiators of the project. NOMAD realized the first sound art festival titled “cntr_alt_del” in 2003, then continued in 2005 and 2007-2008. Nomad developed an important local network and carried out many projects, which evolved into networking and projects combining contemporary art and social issues.

In 2006, Ekmel Ertan and Aylin Kalem, then colleagues at Bilgi University, organized TECHNE Digital Performance Platform, which was the first new media event of its kind in Turkey. It was a one-week festival, consisting of a small exhibit, seminars, two dance performances and a few workshops around new media.

Until 2007, there were only a few academics and some individuals in the developing Turkish new media field and the need for an independent institutional organization was clear. Some of the people who worked together in TECHNE started Body Process Arts Association (BIS), which is the first and only independent NGO in the field. BIS initiated by Ekmel Ertan, Özlem Alkış and Nafiz Akşehirlioğlu, who started amberFestival (amber Art and Technology Festival) in the same year (more on the amberFestival later).

BIS has curated six festivals since then, all of which were very successful in creating international visibility for the art and technology field and new media art in İstanbul. In November of this year (2013), we will curate the seventh amberFestival.

figure# Track04, Bilgi University VCD Department’s student exhibiton

Few universities’ VCD programs continue to have interesting outcomes. Bilgi University’s VCD department supported an annual student exhibition refered to as Track, marginally influential in the initial years. Track was discontinued in 2010.

In 2006 Bilgi University moved to its new Santral campus, which includes a contemporary art museum on the inspiring terrain of an Ottoman electric plant. This space offered new possibilities for new practices in the field. The Performing Arts Department of the same university contributed by opening workshops and including new technologies in their curriculum. Faculty members Aylin Kalem and Beliz Demircioğlu started the artist group BODIG that provided dance and performance workshops utilizing new technologies. In 2008 Lareate International Universities bought Bilgi University which effectively ended its cultural life. In 2013 the museum was converted into classrooms and its collection that had generated huge enthasusiasm in the Turkish art scene was sold. Debate erupted over the status, ethical rules and regulations overseeing the sale of the collection.

A very promising recent initiative is a Game Lab called “Bug” started by Güven Çatak at Bahçeşehir University. Bug has already designed a few games, collaborated in the making of a documentary about the game industry in Turkey and publishes course documentaries online. The long-term plan is to start a game design department, which will be the first in Turkey.

The Kurye Video Festival has begun to show an interest in new media and has collaborated off an on with EU organizations and realized some new media events which addressed designers and creative industries as audience.

Lately, galleries and museums have also expressed interest in new media; Pera Museum hosted the Japan Media Art exhibition in 2010 and Borusan Music House opened a second media exhibition called “Material and Light”. The director of Borusan Music House has declared that their long-term aim is to open a new media museum in Istanbul. Although they have some new media artworks in their collection, this is not likely to happen in the near future.

The Istanbul art scene, or perhaps more accurately the “art market”, has developed considerably in the last years. More single new media works are part of contemporary art exhibitions. I prefer to call it art market because the arts have been left almost completely to, the private sector; the state is not a real actor in this area anymore. Indeed, apart from the early Republican period when the major art schools were founded, the Turkish state has never really supported the arts. It was in fact quite the opposite. Ataturk Cultural Center which was the 4th biggest venue in the world when it was opened in 1969 and was home of the state theatre and state opera and ballet has been closed down since 2008 for renovations. State Art and Sculpture Museum has been closed for the same -officially declared- reason for the last nine years due to an unending process of renovation.

Only in 2010 -when İstanbul was the European Capital of Culture- the independent artists and organizations working in the contemporary art field was supported by the state for the first time, through the İstanbul 2010 ECC Agency. That experience showed us that no practice or procedure through which artists and the state can work together had been developed. Today‘s art scene is primarily comprised of national corporations which support their own cultural institutions, with some commercial galleries for a small elite audience and collectors. Therefore corporations and a small group of galleries and collectors have been leading the art scene.

Since the mainstream market reacts slower to the changes of the time, and Turkey is just a follower of the Western art scene, what we have managed to get is a conventional art market. This may also be true for many other countries these days; less state money for the arts and whatever is available mostly goes to traditional or conventional arts. However, the complete lack of public money in the Turkish art scene leaves it open to the manipulation of power actors and leaves artists, artist groups, independent institutions, etc. in danger of losing their voice.

In an art scene like this, it is difficult to find your way as a young artist, especially if you are working in a niche. As I mentioned before there are only a few artist in Turkey who have developed a career in new media.

figure# News Knitter, Ebru Kurbak and Mahir Yavuz

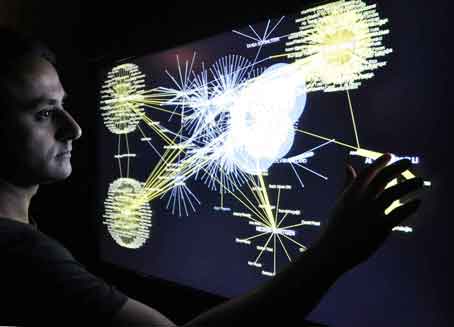

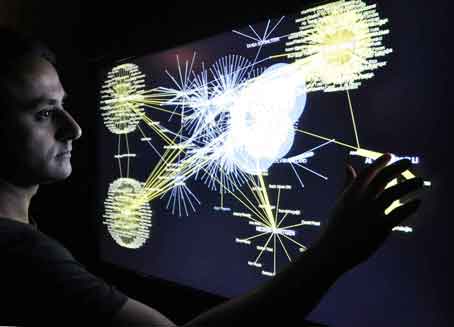

Burak Arıkan is the best-known Turkish media artist. He studied at MIT after completing his civic engineering education and master’s degree in media design in Turkey. He is the most productive artist in the field. During his education at MIT he worked on different topics and collaborated with many international artists. Lately he works on Network Mapping, which he developed as an artistic tool to analyze social relations among actors in many different fields, but especially in the art scene. One of his notable works is Mypocket.

Mahir Yavuz and Ebru Kurbak became especially known for their collaborative work called News Knitter. They created pullovers that visualized large scale data; specifically news images about the Turkish military. It is partly a political work consisting of data collected by Google which does searches for a certain time period. The information is then processed with custom software to create the visualization. After completing their graduate education in Turkey, they both moved abroad for their PhD study Yavuz now works and lives in NYC. Kurbak completed her PhD and works as an establised artist and researcher based in Vienna.

figure# Artist Collector Network, Burak Arıkan

Ali Miharbi is another media artist who completed his higher education in the United States. Miharbi works with face tracking software and most of his recent work is based on related concepts. Among his works are Delegation and Faces on Mars. He also wrote RTÜK, a plug-in written for Firefox which lets ordinary users ban those parts of websites that they believe are unsuitable. It’s a critical work in protesting the state’s internet policy.

Onur Sönmez is a young artist who completed his graduate study at Linz after his undergraduate studies at Bilgi University. Sönmez started his career as a designer and worked as a research artist at Future Lab. He lives and works abroad as an artist and researcher. Among his works, which cover a wide range, are The Mexican Standoff, Jason Shoe, and White Shadow.

Not all of these artists come from a digital background, but they are also not from conventional art education or practices. Of course there are many established artists in Turkey who use new technologies among other techniques and media. I did not mention them here as New Media Artists. Mainly because new media or technologies are not their main medium and even if they create such works, they do not shape their artistic repertoire. Although I believe that these artworks deserve the same merit as others, it is a completely different artistic approach and methodology which distinguish new media artists from the conventional ones.

figure# amberFestival posters

After this brief history of new media in Turkey, I will continue with our own experience, BIS and amberPlatform.

BIS (Beden-İşlemsel Sanatlar Derneği / Body-Process Arts Association) is an Istanbul based initiative that aims to explore artistic forms of expression at the crossroads of the body and technological processes. It was founded in 2007 as an association by a team of researchers and artists from different disciplines such as dance, performance, design, social sciences and engineering.

BIS aims to create an international discussion and production platform. It defines its area of interest in its subtitle. The concept of body-process arts encompasses artistic forms that explore, embody and question the complex, multifaceted relationship and fluid boundaries between body and technology and the consequences of their interaction.

BIS started amber Art and Technology Festival in November 2007 which consisted of a new media art exhibition, performances, workshops, seminars and artist presentations. It has since become an annual event.

amberFestival’s objectives;

– To promote research and production in new forms of artistic expression that exploit new technologies

– To provide visibility to artworks and young artists working in the field of art and technology

– To present international artworks to young artists and the general Turkish public

– To bring critical topics in art and technology to public attention

– To improve young artists’ perception of technology by encouraging active and creative use of it

– To create a new international art and technology network between East and West

figure# amber’10 exhibition

amberFestival has worked on realizing these objectives in the past years and has created a new international scene on the crossroads of art and technology. The themes of the past 6 festivals were “Voice and Survival” “Interpassive Persona”, “Uncyborgable?”, “Datacity”, “Next Ecology”, “Paratactic Commons”; each with references to local as well as international panoramas. This year we focused on smartness, the market-speak of today’s technologically sophisticated conditions, with a critical approach. Festival theme entitled “Did you plug it in?” with a subtitle “fool your smartness”.

In the previous six editions of amberFestival combined, 218 artists and researchers have presented their work; Stelarc, Bill Vorn, Marcel.li Antunez Roca, Mladen Dolar, Robert Pfaller among them. Over 149 installations were exhibited, 26 workshops, 18 performances, 14 lectures, more that 100 paper presentation and talk and 53 artist presentations were realized.

From the first installment of the festival presenting the work of local artists has been an important issue. amberFestival encouraged young artists and tried to make sure that a quarter of the exhibited works were created by local artists. So far, 54 local artists have exhibited their works at amberFestivals. For most young artists it is the first international presentation of their work and a great opportunity for networking.

amberFestival helped create awareness about the Art and Technology field and brought critical topics to public attention. The themes of the festival encouraged broad discussion of important topics related to technology and society. Starting in 2009 with amberConference the topics became even more visible to, and elicited the participation of, a larger audience.

The first international amberConference was held in conjunction with the 2009 amber Art and Technology Festival. amberConference aims at creating a platform of discussion and dissemination of various themes and topics in which science, art and technology converge. Now in its fifth year, amberConference continues in close collaboration with İstanbul Modern, İstanbul Technical University, Sabancı University and the University of Southampton.

figure# amber’10 exhibition

amberPlatform also created or collaborated on other projects abroad and exhibited works of artists who live and work in Turkey. Luna Park was a collaboration with Dortmund based Artsceneco, with exhibitions in Munich, İstanbul and Dortmund. Intercult Playface was an exhibition in Museum Quartier in collaboration with Interface Culture Master program. In 2012 we exhibited new media artworks from Turkey in The Hague, The Netherlands with exhibition title “Commons Tense” in collaboration with local TodaysArts Festival. Part of this exhibition also showed in gallery HBKsaar in Saarbrucken, Germany.

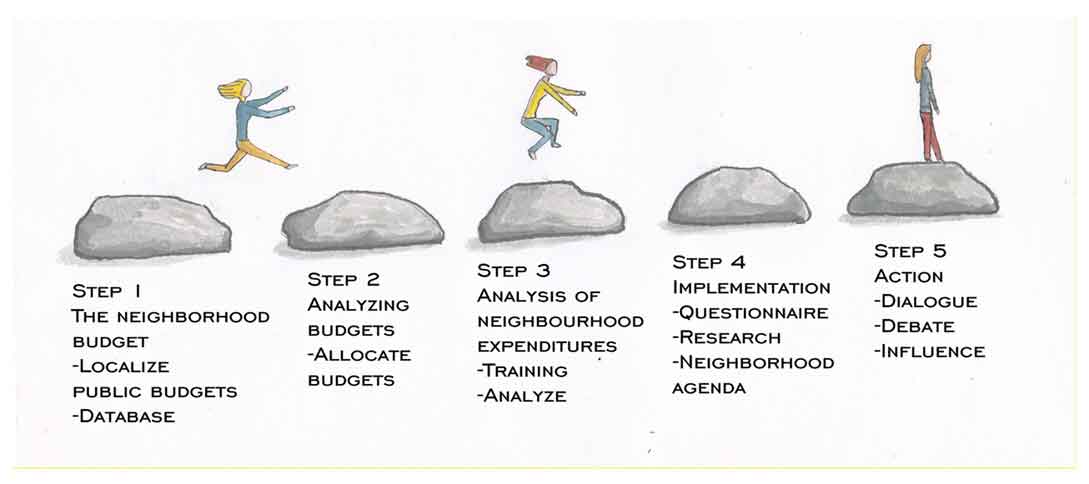

BIS runs several other projects on the crossroads of art, technology and society. I like to mention few of them to picture the wide range of interests and actual works that amberPlatform executes in parallel to its effort in the art scene. The fund raising process for amberFabLAB is about to be finalized and it is expected to be operational in the fall 2013. amberFabLAB will be a fabrication laboratory that aims to democratize the production and to disseminate the making of culture as a node of the international fablab network. Open Data Open City is another ongoing amberPlatform project that aims to build an Open Data Portal and to advocate openness culture and transparency for the state with the help of todays technologies.

BIS remains one of the important actors that shaped, and continues to shape, the art and technology scene in Turkey.

About the author:

Ekmel Ertan, Artistic Director at amberPlatform/BIS, Lecturer at Sabancı University

Read more: http://www.amberplatform.org/

See also: http://www.forumist.com/