Rozenberg Publishers 2004 – ISBN 978 90 3619 341 2

In the life of each organization, situations arise that are completely new to the history of the organization. These situations are complex, surprising, urgent, inspiring, threatening and sometimes enduring. Leadership is forced to bring the organization into uncharted territory. Facing these situations, and often after a period of muddling through in a business-as-usual way, leadership has to recognize that a breakthrough response will only emerge from a previously unexplored (and, for this organization, a revolutionary) strategy process. Think about the bewilderment in a high-tech company when an emerging technology from a competitor threatens the whole existence of their organization.

The California energy crisis in 2002 is another example: by initially oversimplifying the problem and failing to identify and evaluate major alternatives, the state found itself in a crisis of its own making. If there had been proper communication about this complex system among all interested parties (e.g. suppliers, regulatory agencies, distributors, and consumers), it is unlikely that the decisions made would have proven so unsatisfactory. Yet another instance is the dilemma faced by a nationalized railway or postal service – is deregulation an opportunity or a threat? Should they lobby against adoption of a new deregulation law, or pursue it as a great opportunity?

According to William Halal, who assessed the state-of-the-art of strategic planning in his study of 25 major corporations: “Issues can be thought of as stress points resulting from the clash between the organization and its continually changing environment. The magnitude of change is so great now that the social order has become a discontinuity with the past, creating a deep division between most firms and their surroundings that allows the environment to bear against the organization like a drifting continental plate. Issues comprise the societal hot spots that are generated at this stressful interface, forming social volcanoes that often erupt unexpectedly to shower the corporation with operational brush fires” (Halal, 1984, p. 252).

Two examples of such change are cited in the following pages. Suffice it to say that there is a class of macro-problems in uncharted territory which lead to “bet the organization” decisions.

How to Enter an Unknown Land?

Much has been written for leaders of organizations about the need to improve the quality of strategic decision making when one is faced with conditions of turbulence and revolution. Decisions have to be taken faster, they have to be more creative, they must draw on the wisdom of many, and they also need the commitment of several internal and external stakeholders. Academic and popular writers on strategy and policy mention the growing complexity and turbulence of the environment, the growing interconnectedness of organizations, and the growing importance of stakeholder participation and organizational responsibility. Management must become aware of the need to flatten the organizational structure because of increasing knowledge intensity and the escalating professionalism of work.

This is just a short list of the underlying causes for the need to dramatically change the style and process of strategic management. When entering terra incognita, leadership has to ensure that those involved in policy development create consistent, doable, relevant and creative strategies. These must be based on a shared understanding of context and totality, an inspiring image of the future, clear value tradeoffs and well-tested and explored alternatives for action. How is it best to realize all these demands? How can all of this be brought to life in a typical conference room? That is the question the book Policy games for strategic management – Pathways into the unknown addresses. We want to show how a discipline called gaming/simulation can help organizations to realize these objectives.

There are reasons enough to become somewhat cynical when one reads the above summary. Many limiting factors in the capabilities of even the wisest individuals and the best-run organizations make it very difficult to even begin to live up to the standards of decision making now required. There are always time and resource constraints, and there is the basic human tendency to simplify complexity. Because of differing (and often conflicting) perspectives pertinent to the many disciplines and functions present in every large social structure, organizations frequently face severe communication problems. Within and between organizations, many opportunities for cooperation are never explored because of real or perceived differences in values and interests. There is often a lack of talent, imagination and/or patience to examine a strategic issue thoroughly instead of adopting the most obvious alternatives, which are easiest to implement given the existing balance of power.

Policy Exercises: Preparing for the Unknown

In the book, we analyze the structure of strategic problems in uncharted territory and explore what it takes to handle these problems. We show in detail how certain organizations have successfully dealt with them, using the policy exercise methodology based on the discipline of gaming/simulation. Experienced and responsible clients and observers of this methodology have evaluated this approach as very effective and practical. To stay in line with common practice, and also for stylistic reasons, we use the terms “policy exercise” and “policy game” synonymously.

The policy games presented in the book were created as “safe environments” where people who have a key role in confronting major problems can bring their knowledge and skills to the forefront of the strategic debate. They provide the opportunity for “as real as possible” experiential learning to mobilize core competencies and test the skills that may be needed in the future. They help to develop confidence and ownership and reduce the fear of the unknown.

Games have an important role in making sure that strategies are doable in the eyes of the doers. The basic assumption and thus the message of this book is that gaming/simulation is a powerful strategic tool for organizations which are required to enter uncharted territory. A gap exists between the gaming discipline and the literature on strategic management. In professional and academic journals on policy, strategy, and organizational change, one finds little about successful gaming applications. This is unfortunate, because a properly devised gaming/simulation rapidly enhances the sophistication of the participants. The technique is particularly well suited for circumstances where the objectives are to provide an integrative experience, illustrate management techniques in an experiential manner, develop esprit de corps among a group, convey an overview or systems “gestalt” (the big picture), and provide an environment for experimenting with improving group process. Gaming/simulations offer a fruitful potential for melding many skills.

The Goals

Two goals motivated the authors to write Policy games for strategic management – Pathways into the unknown. These aims are inseparably intertwined but require independent logic to be properly addressed:

• We want to contribute to the further development of the discipline of gaming/simulation as a method to solve strategic problems; and

• We want to improve communication between our discipline and the related policy disciplines.

The current state of the gaming/simulation discipline is represented by a wide array of formats in projects where this technique has been employed worldwide. To the uninitiated, this great variety (scope, purpose, subject matter, technique, nature of the product, etc.) implies that gaming/ simulation is all things to all people. The image conveyed does not contribute to the credibility of the discipline.

The irony, of course, is that the allied fields of policy, strategy, and organizational change are each well-established users of gaming/simulation. The difference is that each of these fields tends to select gaming applications as specifically appropriate to their need. As a consequence, colleagues from these fields are often unfamiliar with the broader spectrum, the history and the methodology of the discipline of gaming/simulation. Policy issues must increasingly be resolved under conditions of complexity and there are few effective techniques for dealing with these situations. With the book, we want to show that a well-understood, clear, replicable and practical method to create policy games exists for the unique decision situations that organizations sometimes face.

Key Concepts

The more conceptual parts of the book analyze the gaming/simulation approach. This approach is relevant for strategic problem solving because – in a well-structured, transparent and effective way – it can put into operation a large number of the lessons that have emerged from the literature that deals with resolving macro-problems. To capture these lessons in a tangible format, we define five key process criteria for handling macro-problems or “bet the organization” decisions. We have labeled these criteria the “five Cs”: complexity, communication, creativity, consensus, and commitment to action. We give a short introductionto these key concepts below.

Complexity

Macro-problems are complex from a cognitive point of view. Framing such problems correctly is difficult. There are many variables involved, but no one knows what and how many the important variables are. The same is true for the relationships between the variables. The causes of the problem are often obscure, and so are the future trends. There is no overview or solid past knowledge of how to act vis-à-vis this problem. Usually, many potentially relevant sources of knowledge are available, but the existing knowledge household might prove to be scattered and incomplete, and its elements are often of unequal quality. It is not available in a format useful for decision making, nor is it shared by the relevant people.

In the case of the IJC Great Lakes Policy Exercise, the policy exercise designers had to identify and cope with close to a thousand variables. The exercise was intended to help the assembled group arrive at a holistic understanding of a complex problem. This could only happen if the “shared images of reality” were viewed as authentic by a clear majority of the hundred (or so) policy makers as they debated the best course of action to pursue (this story is told in Chapter 3 of the book).

The first criterion for entering the terra incognita of macro-problems is that one must apply a method for handling the complexity of such a problem. As we will demonstrate, gaming/simulation can produce policy exercises in which many different sources and types of data, insights and tacit knowledge can be integrated in a problem-specific knowledge household. Furthermore, these policy exercises provide an environment that allows the exploration of possible strategies for entering uncharted territory. These games offer a safe environment to test strategies in advance. They help decision makers to create a possible future and allow them to “look back” from that future. We call this capability of gaming “reminiscing about the future” (Duke, 1974).

Communication

Communication is essential when important decisions are to be made. There are not many organizations in which one individual has the authority to make strategic decisions alone. Even when a final decision will be taken by a single individual or a limited number, these top decision makers have to rely on and collect the wisdom of many people within and beyond the borders of their organization. In complex situations where a group must resolve a perplexing issue, traditional modes of communication have proven not to work very well. New methods are needed which provide an overview and stimulate gestalt communication. The book will show that policy games, if applied properly, are a hybrid form of communication. They are hybrid in the sense that they allow many people with different perspectives to be in communication with each other using different forms of communication in parallel. We label this the multilogue characteristic of policy games (Duke, 1974).

Creativity

In many cases, problems can be approached with new combinations of proven and well-tested lines of action. But this can only be done if the analysis of the problem leads to the “aha” effect of recognizing the analogy between the new situation and familiar examples. Discovering analogies is basically a process of creativity: it needs the playful exchange of perspectives and the retrieval of intuitive or tacit knowledge. Accumulation of experience in a person, a team or an organization leads to the development of a repertoire of responses to many different challenges. As Mintzberg (1994) points out, finding the appropriate response to a challenging issue is not a science, but a craft. It is about combining experience with creativity to find a new, original, inspiring and adequate pathway into the unknown. To the extent that science does not have a complete answer, the policy exercise can provide a disciplined approach that requires confronting the known and the unknown.

‘[S]cience is an endeavor in which one gets such wholesome returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact” (Mark Twain)

The Dutch philosopher Johan Huizinga (1955) has made a major contribution to the understanding of the fundamental link between play and creativity. In his famous study on man as a player (Homo Ludens), Huizinga puts forward the thesis that innovation can only be achieved by play. In the free and safe activity of play, and consequently in the free spirit of a playful mind, the individual can go beyond the borders of the limiting forces of everyday life. Only through play can new combinations be developed which, according to Schumpeter (1934), is precisely what innovation means. Policy exercises combine the realistic element of simulation with the playful stimulus of gaming. People in roles explore the dynamic consequences of the available knowledge base in a free and stimulusrich environment. They test each other’s responses to trigger novel alternatives and to challenge and play with any idea that seems to have potential.

Consensus

New challenges often bring out old, and sometimes unsuspected, conflicts of values. Organizations in a steady-state situation have often developed a balance in “frozen” conflicts. In most organizations, conflicts of values and interests have been brought to rest. They have resulted in workable arrangements: compromises that reflect the existing power balance. In short, there is a workable degree of consensus. But in turbulent times, in periods of transition, and under the strong pressures of major challenges, this consensus will be tested. The power balance might shift because the owners of new and suddenly relevant resources (skills, knowledge, networks, capital, etc.) want a stake in the issue. Newly affected parties appear in the arena and the old supporting stakeholders may become marginal or even hostile. As a consequence, “new rules of the game” have to be defined. There is a need for a new consensus, which, preferably, should not be the result of a long and costly battle in the period after a strategy has been chosen. The concerted action and support of many stakeholders is needed to deal with major problems. Gaining understanding (with regard to complexity), finding a novel course of action (with regard to creativity), and the negotiation of consensus should all be part of the process of communication which precedes the adoption and implementation of a strategy. A painful and conflict-ridden collective thought experiment is much more desirable that a conflict-ridden and stalled implementation process.

The simulation character of policy games helps to avoid a major threat involved in other forms of finding a consensus. When a group of people reaches consensus without proper analysis or without looking beyond the borders of traditional perspectives, there is a real danger that only politically feasible and easy-to-implement strategies will be discussed. In the literature, this is called “group-think” – and the history of organizational decision making is full of fateful examples of this phenomenon.

Policy games are “social simulations” (Van der Meer, 1983) in the sense that they model the social organization around an issue. They put real people in roles as caretakers of certain interests and positions and distribute resources as in real life. They allow players to explore the consequences of the issue at hand within the existing structures and rules. In a game, one is often surprised to discover that the gains and benefits of a certain strategy affect parties in a completely different way than expected. Win-win options might be discovered, and the “early warning” nature of the game might signal potential win-lose situations at a stage when policy adoptions can still be discussed.

Commitment to Action

People are action-oriented beings. This is especially true for individuals who have a long career of “making things happen.” Of course, strategy without action is not strategy at all. Initiatives lacking the entrepreneurial drive to succeed will soon end up on the pile of good intentions. That is why a good process for entering into the unknown must create a commitment to action for those people whose energy and endurance is vital to the success of the strategy. Charismatic and dedicated leadership is important, but, increasingly, this is not enough. In the de-layered, more knowledge-intensive, more professional and faster-moving organizations of our time, strategy is realized in the day-to-day decisions of many individuals and teams in the work force at the points of interaction with clients and other stakeholders. More and more people are active in realizing a strategy as relatively autonomous decision makers. It is essential that all members of a group move into uncharted territory at the same time. This presupposes that all the individual actors understand the problem, see the relevance of the new course of action, understand their roles in the master plan, and feel confident that old skills or skills to be acquired in due time will help them to conquer the obstacles and seize the opportunities ahead.

A Short History of Policy Gaming

Space permits only cursory attention to this topic. Suffice it to say that there is a rich history of gaming activity and much of it relates to policy concerns. The purpose of this section is to describe the origins and evolution of the policy exercise as a relatively new phenomenon that emerged out of a very old tradition. Games are as old as humankind, and have always had a culture-based learning function. Tribal rituals, games of the young knights in the Middle Ages, the childhood games of our youth; these are all examples of games to internalize rules and master important skills.

Games for Learning

Gaming has been used for centuries as an exercise in military strategy; the technique has also been widely used for other serious learning purposes. Since World War II, gaming has expanded its scope to include theoretical and practical endeavors in every imaginable discipline. Beginning with the advent of training games for business, the field has broadened to embrace the social sciences and educational needs of modern society. Information and communication technology has fundamentally changed (and will keep on changing) the gamer’s toolbox. The new technologies have given the gaming discipline an enormous boost. Improved computational, graphic and communication methods have resulted in games with more dynamic realism, a much shorter production time, and simpler facilitation procedures. The element of simulation can also be found in games from the past. In their extensive study of the history of games and play, Gyzicki and Gorni (1979) found that backgammon is the oldest known board game in the world, dating from 2450 B.C. Backgammon, of which many varieties exist all over the world, simulates a match on a track court.

Early War Games

Sun Tzu

The origin of war games is unclear; however, it is likely that chess was one of the earliest versions of this activity. The game of chess, originating in the army of India around the fifth century, simulates a war between kingdoms. Not only the shapes of the figures, but also the hierarchy and the mobility of the pieces represent the structure of an army from that period. Shubik (1975) found concepts of gaming and elements of a theory of strategic gaming in the writings of a great Chinese military genius, the general Sun Tzu (original about 500 B.C., republished 1963), whose book on the “art of war” is still widely read.

Certainly there is a great similarity between chess and many of the later versions of war games played on a board as the symbolic equivalents to warfare. They represented abstractions of military confrontations, and by the turn of the 18th century, they were formalized to ensure consistency of play governed by rules and standardized penalties. Significant changes were introduced into the “new” German war games in that actual maps (instead of a grid game board) were used, and a greater complexity was introduced into the decision structure. By the 19th century, because of the different requirements for “realistic” as opposed to “playable” games, their construction split along the lines of “rigid” and “free” games. Both versions tended toward a higher level of sophistication, but whereas the former version relied heavily on formalized procedures to govern play (maps, charts, dice, extensive calculations), the free games substituted the judgment of experienced umpires to expedite the play. Both have been employed as techniques for analyzing and evaluating military tactics, equipment, and procedures.

Casimir (1995) studied two 19th century German textbooks on war gaming in the library of the University of Göttingen. In Von Aretin (1830), Casimir found a discussion on the development of war games between 1664 and 1825. Von Aretin sees a development of constant decrease in the level of abstraction and a growing complexity of the games. Casimir quotes Von Aretin’s very modern-sounding opinion on the value of the war game as a tool for training: “that playing a game is better than listening to long, tiring, half-understood and quickly forgotten lectures or paging for hours through books” (Casimir, 1995). In Meckel (1873), Casimir found a summary of the many advantages of war games compared to other forms of learning, such as practice in giving and receiving orders. This, as Casimir rightly points out, is quite comparable to modern experiences with the use of games to train for teamwork (Geurts, et al., 2000).

The two major forms of war games, free play and rigid play, still exist. Both are used as techniques for analyzing and evaluating military tactics, equipment, procedures, etc. The free-play game has received support because of its versatility in dealing with complex tactical and strategic problems and because of the ease with which it can be adapted to various training, planning, and evaluation ends. The rigid-play game has received support because of the consistency and detail of its rule structure and its computational rigor. In addition, the development of large capacity computers has made it possible to carry out detailed computations with great speed, and thus enabled the same game to be played many different times. These developments have allowed for an increase in the number and types of war games.

Concurrent with these developments, there has been an increased popularity of war gaming, and the technique has spread to other countries. Initially, West Point copied various British versions, and war gaming developments have continued in the armed forces to the present. Prior to World War II, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto convinced the Naval General Staff to stage a theoretical attack on Pearl Harbor during the annual naval war games. During the early days of the Gulf War, some 50 years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, newspapers reported that Norman Schwartzkopf had been given operational responsibility for this mission in Kuwait and Iraq. Schwartzkopf was selected because he had prepared a new and surprising strategy for this mission in a war-gaming exercise. These are just two of many instances where military leaders have utilized games for both training and problem-solving purposes. One thing is clear: war gaming is a very important predecessor of the form of policy gaming described in the book.

Modern War Games

Over a 3000-year period, the prime use of war games has been for instruction. However, they have also been used for analysis (as in the Pearl Harbor incident), particularly with respect to testing alternative war plans. The Axis powers made more extensive use of war games during the period leading up to World War II than did the Allies.

In addition to the Japanese Naval War games previously mentioned, the Japanese Total War Research Institute conducted extensive games. Here, military services and the government joined in gaming Japan’s future actions: internal and external, military and diplomatic. In August 1941, a game was written up in which the two-year period from mid-August 1941 through the middle of 1943 was gamed and lived through in advance at an accelerated pace. Players represented the German-Italian Axis, Russia, the U.S., England, Thailand, the Netherlands, the East Indies, China, Korea, Manchuria, and French Indochina. Japan was not played as a single force, but instead as an uneasy coalition of the Army, the Navy, and the Cabinet, with the military and the government disagreeing constantly on the decision to go to war, X-day, civilian demands versus those of heavy industry, etc. Disagreements arose and were settled in the course of an afternoon with the more aggressive military group winning most arguments. Measures to be taken within Japan were gamed in detail and included economic, educational, financial, and psychological factors. The game even included plans for the control of consumer goods, which, incidentally, were identical to those actually put into effect on December 8, 1945. Postwar military gaming efforts have reached high levels of sophistication, approaching the ingenuity displayed by science-fiction writers. There have been other extensive war gaming developments since the advent of the computer. For reference purposes, see Shubik (1975), Brewer & Shubik (1979), Osvalt (1993) and Boer & Soeters (1998). On a happier note, gaming efforts are now being directed towards the pursuit of non-military purposes as evidenced by the examples.

Positioning Policy Games

The above section has made clear that gaming/simulation has a long tradition and that games can have many forms and functions. Although we explain our view on the policy exercise in more detail in later chapters, this introductory chapter provides an initial definition and positioning of policy games.

Meaning of Play – Central Characteristics

J. Huizinga – Homo Ludens

Play is a central human characteristic; a basic counterpoint to life itself. The Dutch philosopher Johan Huizinga has probably contributed the most to the systematic analysis and philosophical interpretation of the concept of play. Huizinga (1955, p. 1) views man as a game-playing animal: “play is to be understood … not as a biological phenomenon but as a cultural phenomenon. It is [to be] approached historically, not scientifically.” Huizinga notes that animals play, therefore playing is not solely a human activity. Games have been a fundamental aspect of our lives from infancy. There is both playful play and serious play (e.g. Russian Roulette as a pastime by soldiers on the front line). Huizinga claims that play is the basis of culture from which myth and ritual derive. In his book Homo Ludens, he finds several elements that define a game (see also Geurts, et. al, 2000). In this context, he states that play:

• Is a voluntary, superfluous activity (one enters into it out of free will);

• Is stepping out of real life into a temporary sphere of activity;

• Means being limited in terms of time and place;

• Has fixed rules and follows an orderly process;

• Promotes the formation of new and different social groupings;

• Is itself the goal; and

• Is accompanied by a sense of tension and joy and the awareness that the activity is different from normal life.

There seems to be a contradiction here: is a game only a game if the activity itself is the goal? For Huizinga, game and play are the main forces for cultural change and innovation: only by stepping out of the ordinary routine of everyday life will individuals discover new routes and perspectives. “Culture arises in the form of play,” says Huizinga (1955, p. 46). There is only a hazy border between play and seriousness. Just as humankind is able to develop more and more games for joy and entertainment, in the same way, there seems to be no limit to the fantasy of people when creating games in which creative and learning effects are directed towards a consciously chosen “outside-the-game” goal.

Comparison of Simulation vs. Gaming

Gaming is valuable in part because it responds to a human need – people crave information: they enjoy exploring, discovering and learning. They do not like just to be told about something; they learn most readily from concrete instances and information strong in imagery. A simulation generally involves a detailed representation of reality in a computer whereas, in a game, the players are the central part of the model construct. Gaming has some valuable features:

• It is an explicit statement that provides a framework that incorporates player strategies in an integrative structure;

• It permits players to employ these strategies in a group process;

• It provides the opportunity to break through old interpretative frameworks; and

• It brings many ideas to bear on the problem at hand.

What is simulation? The Latin verb “simulare” means “to imitate” or “to act as if.” Duke (1980) defined simulation as “a conscious endeavor to reproduce the central characteristics of a system in order to understand, experiment with and/or predict the behavior of that system.” To be able to simulate the behavior of a system, one creates or uses a model of that system. Leo Apostel (1960, p.160) defines a model as follows: “Any person using a system ‘A’ that is neither directly nor indirectly interacting with a system ‘B,’ in order to obtain information about system ‘B,’ is using ‘A’ as a model for ‘B.’” Simulation models are specifically made to help clients understand the systems in which they are embedded.

A model can have many different forms: a road map, a three-dimensional representation of a building, a mathematical algorithm or a complex computer program possibly accompanied by graphical representation. A gaming/simulation is a special type of model that uses gaming techniques to model and simulate a system. A gaming/simulation is an operating model of a real-life system in which actors in roles partially recreate the behavior of the system. The word “partially” refers to the fact that a game can contain many other elements that play a part in simulating the system, such as maps, game pieces (e.g. poker chips) and computer software . The game invites the players to jointly create a future from a starting position.

Step by step, they make decisions, alter cooperative or competitive relations, and act within the rules of the game on the basis of their joint or individual insights and preferences. The policy exercise can be thought of as a small group problemsolving technique that offers a means of experimenting with the management of complex environments (these are often called “wicked problems”). The approach clarifies these problems and demonstrates to managers the need to be proactive in exploring a variety of solutions before a decision is taken.

A simulation is an operating model of the central features of a system; that is, it shows functional as well as structural relations (Greenblat, Duke, 1975). Some simulations are operated within computers, other types are performed by human players. This eliminates the need to build in psychological assumptions. The actions of players within the game consist of a set of activities aimed at achieving goals in a limiting context with many constraints. At this point, a clarification of terminology is important since this definition of gaming/simulation encompasses a wide range of exercises. Business games, war games, operational gaming, management games and other exercises with a great variety of prefixes fall into this category. The function of these gaming/simulations will vary. There are exercises to motivate a group, ice-breaking activities, games for education and training in schools or organizations, and games for policy making. Our focus is on the latter and we will start to explore them in the next section.

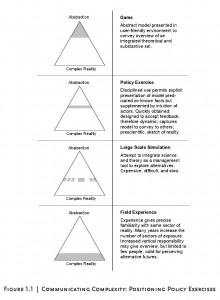

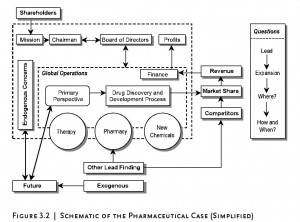

Figure 1.1 helps to illustrate the nature of these different approaches. The figure shows that the level of abstraction appropriate for policy exercises can be placed between very abstract games and very detailed large-scale simulations that prove useful for operational planning in well-understood areas.

Figure 1.1

Policy Games: One Form of Gaming/Simulation

A policy exercise is a gaming/simulation that is explicitly created to aid policy makers with a specific issue of strategic management. A policy exercise will function as a managerial support process that uses gaming/simulation to assist a group in policy exploration and execution. A large and growing number of professionals devote a substantial part of their energies to the effective use of gaming/ simulation tools. In each new situation, the professional has to complete essentially the same sequence of activities:

• Validate the decision to use this approach;

• Clarify the client’s needs;

• Structure the problem effectively;

• Develop a prototype exercise;

• Test and modify the prototype;

• Deliver the exercise to the client; and

• Evaluate the final product.

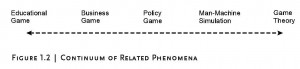

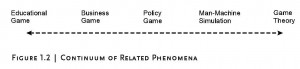

A major characteristic of the policy exercise approach is that it allows players to experience the complexity of strategic problems and their environments. It allows the players to understand the interaction of social, economic, technological, environmental and political forces that exist in planning and decision making problems. The objective of a policy game is to create an operating model of the problem environment that is general and structural. The use of a game employs a process that lets the participants debate the model; it also makes the model vivid so that it will be retained. As a consequence, facts and particulars will be better understood (bits and pieces now have a logical place to be stored). It is best to think of the policy game as falling along a continuum of related phenomena ranging from sports and pastimes, educational games, policy games, manmachine simulations, and pure simulation to the mathematical theory of games (Figure 1.2)

Figure 1.2

Meier (1962) described gaming/simulation as “invention in reverse”; it transforms a macro-phenomenon into a workable exercise. The degree of compression in time and scale must achieve a reduction or magnification of several “orders of magnitude” as it combines experience with technology, frequently using trial-and-error methods. There is the challenge of retaining verisimilitude while selecting one part per million. The challenge of designing an exercise is well stated by Meier & Duke (1966, p.12): “… the real challenge is to reproduce the essential features of a (complex system) in a tiny comprehensible package. A set of maps is not enough. Years must be compressed into hours or even minutes, the number of actors must be reduced to the handful that can be accommodated in a laboratory …, the physical structure must be reproduced on a table top, the historical background and law must be synopsized so that it can become familiar within days or weeks, and the interaction must remain simple enough so that it can be comprehended by a single brain. This last feature is the most difficult challenge to all.”

The policy exercise method uses a variety of design features to ensure a seamless integration of the final product. Both Richard E. Meier (1962) and Harold Guetzkow (1963) have emphasized simulation as an “operating representation of the central features of reality.” The list of techniques from which to draw is long; however, these are central:

• The selection of critical variables

• Contrived face-to-face groups

• Role playing

• Time compression

• Scale reduction of the phenomena

• Substitution of symbolic for alpha-numeric data and vice versa

• Simplification

• The use of analogies

• Replication

A policy exercise typically involves extensive preparation and analysis of the system being addressed, setting the stage for a workshop where expert participants work through scenarios from various stakeholder perspectives. The game is made to represent the current situation in an organization; very often the policy exercise is used only once. That means that great care has to be given to the aspects of validity, reliability and credibility. The policy exercise is designed to provide a shared image of the complex system under investigation. This enables participants to communicate about the issues, appropriate strategies, and the probable impacts of policy decisions. To be able to deliver these services to a client, the game designer has to use a wellstructured design process. Given the nature of policy games, this design process must include:

• Techniques from model building (to represent the system);

• Concepts from strategy theory (how to model the strategic “space”);

• Design techniques for ad hoc work environments (ergonomics; e.g. players have to be able to handle the materials and master the rules and steps of play); and

• Techniques involving arts and crafts (e.g. creating visual representations).

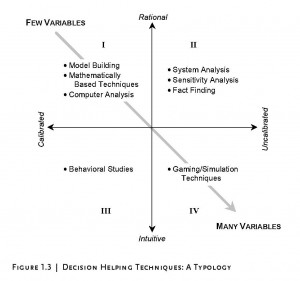

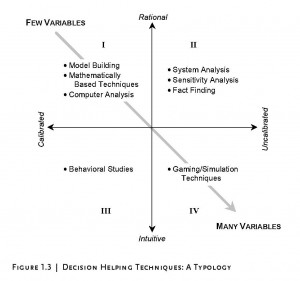

Armstrong and Hobson (1973) have developed a useful diagram (Figure 1.3). If simulation (Quadrant I) can be described as the reasoned reaction to complexity.

Figure 1.3

Simulation (pure Quadrant I mathematical simulation) cannot be used as a foundation for the synthesis of complex systems to invent new patterns. Simulations only allow you to repeat history – they do not permit a group to “play” with new ideas, whereas games allow a group to “invent” the future. Simulation must be exclusive in the variables it incorporates; a game is inclusive and forces players to confront these factors even though they are vague. Simulation is useful in purely scientific environments (e.g. sending humans to the moon) where the environment is data-rich and the solution must be mathematically correct. However, in dealing with problems that have Quadrant IV characteristics, there is a risk of over-reducing complexity and oversimplifying the problem. If a Quadrant I technique is used in a Quadrant IV environment, things must be rationalized, measured, logically structured, quantified, and carried through a logical process that gives logical results. Incorrectly employed Quadrant I techniques can produce a self-fulfilling prophecy; on the other hand, a properly used policy exercise can, and often does, produce profound counterintuitive results.

Towards a Professional Gaming Paradigm

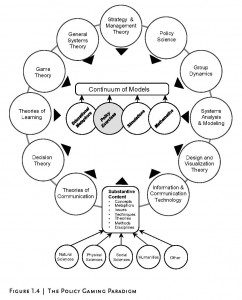

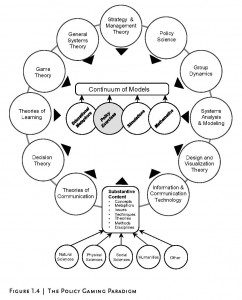

The gaming/simulation approach to strategic problem solving described in the book is a multidisciplinary and eclectic modeling methodology. It is nurtured by and uses theorems and techniques from a wide variety of professional and academic fields. Humankind has created many areas of expertise, each with its own knowledge, tools, recipes and specialized skills that are potentially relevant when designing a strategic game to analyze a perplexing strategic problem. Figure 1.3 positions policy exercises on a continuum of modeling techniques that are reflected in the main disciplinary and professional areas the reader will encounter in this book. The book will hopefully convince the reader of the added value of the risky but stimulating adventure of crossing the borders of the many mature and fast-moving disciplines that appear in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4

Multidisciplinary oriented academics, like the authors, are motivated by strong ideals of enlightenment, relevance and the unification of science. However, they run the risk of falling into the trap of academic hubris or even worse, of propagating and using half-understood or obsolete knowledge from fields that are not their own disciplines. There is only one good preventive line of conduct to avoid these fallacies: dialogue with specialized colleagues: in our case, with the disciplines of organization and strategy.

Case One – Strategy Making in a University Hospital

The Client

As far as the strategic agenda for the University Hospital was concerned, there were several issues that needed hospital-wide thinking and concerted action. For example, the future patient flow was expected to change radically, from inpatient care to outpatient care. One of the forces behind this was the need to reduce healthcare costs. The case is a good example of some of the core functions of gaming. It is about collective futuring in a safe environment in order to experience the problems of current strategic patterns and to explore new and more productive lines of behavior. It is also an interesting example of strategy making in a large professional organization. The intended outcome was not so much a strategic plan of action but rather to improve the strategic capabilities of all the relevant professionals who actually create the future of the hospital in their daytoday actions.

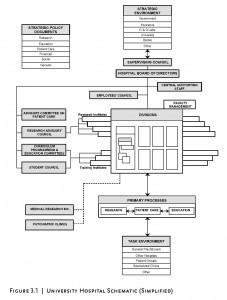

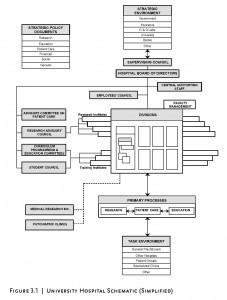

The University Hospital is part of a large Dutch university, and is also one of the most highly regarded medical institutions in the Netherlands. The organization has three primary processes: patient care, research, and education. In the Netherlands, all academic hospitals fulfill these three functions, and the non-academic hospitals usually restrict themselves to patient care. The client hospital was a very large and diverse institution. The many different functional departments all exerted constant pressure internally to search for the optimal contribution to the three primary processes. However, this does not mean that the hospital was not affected by pressures from its environment. On the contrary, one of the more pressing issues at the time of the project was how to respond to an emerging trend in healthcare policy. Increasingly, organizations like the hospital had to work more closely with local peripheral health institutions. The hospital’s initial structure was strongly dependent on the concept of the matrix organization. This proved to be incapable of dealing with the complexity facing the organization. Due to internal and external pressures, a new organization structure had been introduced some eight years earlier. The Board of Directors created a divisional structure that proved to be rather successful. This was based on the business unit structure adopted by many large corporations in the private sector. The model that the new structure followed was the concept of the functional division in which the three primary processes were fully integrated.

Division management was given considerable autonomy to decide on resource and task allocation. In the divisions, medical professionals were “put in the lead.” Cooperation with other divisions was accomplished via contracts, and coordinating structures were created for the training programs and the multidisciplinary research programs. The supervising board took on more of a coaching and facilitating function and formalized the agreement with the divisions in contracts and budget statements. Within the 11 newly created divisions, the managers proved to be successful in managing their own operations and staying within their budgets. External assessments of the hospital research and training showed that the new structure was both efficient and effective: the assessments continued to be rated good to excellent. However, for some members of top management, the new structure created an awareness of a serious danger: perhaps the innovation had been too successful.

The Problem

The division structure had been operational for several years. Some members of the Hospital Board and some division leaders had observed a tendency by the division managers to focus primarily on issues of their own concern. The Board of Directors considered this to be a serious problem. When resources had to be divided over the 11 divisions, the division managers defended the interests of their own division as much as possible. The new division structure and the idea of the medical professionals being in the lead assumed that the division managers would agree on resource distribution while balancing divisional and general hospital interests. It was further assumed that they would be able to do so without strong interference from the Board of Directors; however, this proved to be very difficult. Gradually, some members of the hospital administration began to worry that there was neither sufficient stimuli in the new structure nor a proper attitude to take care of the interests of the whole hospital both now and in the future. At the same time, there was no real interest in reinstalling the Board’s former central powers. The challenge was to solve this danger of a “tragedy of the commons” within the existing structure.

As far as strategic and hospital-wide challenges were concerned, there were several issues that needed strategic thinking and concerted action. For example, in the future, the patient flow was expected to change radically from inpatient care to outpatient care. One of the forces behind this was the need to reduce the cost of healthcare. The Board of Directors, working with the senior managers, identified several problems:

• Within the hospital, there were internal and structural determinants that complicated decision making on organization-wide issues;

• Divisional managers had developed stereotypical behavior that complicated the search for an organization-wide strategy; and

• The hospital as a whole was confronted by a strategic challenge so important that the Board of Directors had to take the initiative to drastically improve joint decision making.

These convictions and insights were not yet shared by all the division executives and central services managers. In order to meet the expected future challenges, a shared awareness and definition of the problem was needed among both the members of the Board and all divisional management team members.

Goals, Purposes, and Objectives

The policy exercise had to fulfill two main goals within the hospital organization. On the one hand, the hospital management needed to become more aware of the problems mentioned above. In that sense, the game had to function as a mirror. On the other hand, the game needed to help the participants explore more productive ways of making decisions that were vital for collective future success. This was called the “window on the future” function of the game. These two goals can be divided into four objectives:

• Participants had to learn about known and unknown strategic challenges within their organization. There needed to be an increased awareness of the problems of the internal organization and in the rapidly changing external environment;

• Therefore, the participants needed to develop a joint problem definition. The game needed to help them to communicate about the general organizational obstacles;

• Participants had to learn to act more flexibly. This was unavoidable in the complex organization of the hospital environment; and

• The game needed to stimulate the participants to develop a more positive attitude towards change. It had to motivate employees to consider important conditions for change in the organization.

Why Did the Client Select the Policy Exercise Process?

The Board of Directors had tried to communicate their concerns about the problems through a report and several discussion meetings, but this effort had no serious effect on the behavior of the relevant managerial echelons. For this reason, they adopted a Board member’s suggestion to apply the gaming technique. This member of the Board had heard about the potential experiential learning power of the gaming tool. He was convinced that top professionals working in the hospital would be more open to this involving and confrontational type of interactive learning than they had been to reports and non-committal discussions.

Specifications for Policy Exercise Design

The exercise was designed for use in an eight-hour framework that included the introduction, playing time, and a debriefing session. The game was designed for 36 people and was to be used only once. The exercise was initially intended for the Board of Directors and Division Management. During the interviews in the systems analysis phase, it became clear how important the department heads were for the gamed problem (departments are units within the division usually chaired by a professor). Several of these senior professionals indicated that they did not want to be excluded. After careful reconsideration, the Board of Directors decided to involve the department heads. Finally, the following participants were selected:

• Hospital Board of Directors (4 people);

• Divisional Management Teams (11 times 3 people: a senior professor as chairman, a manager of patient care and a finance and operations manager); and

• Department heads (variable numbers).

The Schematic: A Model of Reality

Figure 2.1

A schematic of the problem was developed in an attempt to create a visual presentation of the internal and external characteristics of the hospital (see Figure 2.1). The initial description of the problem environment usually emerges in discrete, partially organized, and sometimes conflicting pieces. It is the task of the research team and the client to synthesize these elements of the system into an integrative and explicit model that can be easily described and discussed. The objective is to develop a graphic on a wall-size chart which contains the “Big Picture,” or an overview of all the considerations that might be significant to the policy issue being addressed by this process. This schematic is an indispensable element of the game design process and its use brings about some surprising results.

The schematic is discussed more fully in Chapters 7 and 8 in the book.

Description of the Policy Exercise

The design team followed a formal process to create, employ, and evaluate the policy exercise. Only a few steps central to the understanding of the significance of the exercise are described below. The design team consisted of four external gaming specialists and two members of the hospital organization. This team had several meetings with an ad hoc advisory group within the hospital. The design team studied a large number of documents and

interviewed many representatives of the managerial echelons. A number of external experts were also interviewed. A period of 15 weeks elapsed between the initial agreement on the project contract and the final use of the game. In cooperation with the client, the consultants decided to develop an open game format. In this case, it was not important that the effects of decisions be simulated in a detailed way (the participants were expert enough to know what the results of certain actions would be). What was needed was a very flexible form of role play on the basis of one or two scenarios about the future. The game needed to start with steps of play that mimicked the normal routine of decision making. The game was to be observed by external experts. Both the experts and the players were able to ask for timeouts to discuss and possibly improve the style of collaboration and negotiation.

The scenario was as follows:

It is now January 2003. The strategic plan for 1997 (the year in which this game was played) is valid. The organization has not changed much compared to 1997, but some relevant developments have taken place in the meantime. The emphasis has been put more and more on the transformation of care to permit patients to be increasingly cared for in their own environment. For this hospital and other large hospitals, this has led to a radical decrease in the number and duration of admissions, while the number of outpatient treatments has clearly risen. The Ministry of Health, with the support of the Association of Academic Hospitals, has approved the enlargement of the hospital’s outpatient clinic to twice its current size; by the end of 2003, a plan of implementation has to be ready. The plan has to be neutral budget, which means that the resources have to be reallocated internally. In addition, the plan must be supported by the Board and the managers present at this meeting.

Major Sequence of Activities

Pre-Exercise Activities – The Hospital Board sent personal invitations to all participants announcing the date of the Hospital Strategy Simulation. To give the participants enough time to prepare, the organization took great care to provide clear information concerning the goals to be reached. The invitation to all participants asked that they contribute to the realization of the plan. In the plan, many deciions had to be made, including the distribution of the budgets for the divisions (for research, education, patient care and personnel). The participants had to decide how these decisions were to be made, by whom, and when. All participants played roles that corresponded with their real positions within the hospital organization. In the game, the hospital had six divisions with corresponding management teams. The board was fully represented and present during the exercise. Several department heads played the roles of the leadership of the coordinating research and education programs, positions they also held in real life.

Policy Exercise Activities – The participants started play in the morning with a rolespecific brainstorm session about the consequences of the enlargement of the outpatient clinic. They had to take into account the consequences for budgets and personnel and the effects on research, education and patient care. The remarks were written on flipcharts and, after the brainstorm session, every team had to give an opening statement; this technique ensured that all the participants were informed about the others’ points of view.

The next step consisted of deliberation and negotiation. The participants had the opportunity to meet other teams to talk about the proposed approach for doubling the size of the outpatient clinic. Important aspects of this part of the session were continuous consultation, lobbying, and informal decision making. After that, a meeting was held between the Hospital Board and division chairpersons. The other players were the audience; however, they were permitted to intervene with written questions. In the afternoon, a new cycle started. Each original team had a new opportunity to offer a brief opinion about the outpatient clinic and the negotiations and meetings. The Board provided a response to these interim statements and some observations by the external experts were discussed. For the second time, the participants had the opportunity to meet other teams informally and talk about the plan. This was followed by another meeting between the Hospital Board and the division chairpersons. The other teams served as the audience and were permitted to intervene.

Post-Exercise Activities – Finally, an extensive and lively debriefing session was held with the players and the consultants. Summaries written on the overheads were used to extract interesting remarks, and to explore the ambitions of the participants. The objective of the last activity of the exercise was to evaluate and learn from the sessions. Questions addressed included: What have we achieved today? What have we done differently than usual? Did we do better than normally? What do we have to do differently from now on? Each team had to summarize its deliberations on an overhead sheet, and these were used in the critique. Questionnaires were completed before and after each cycle of play. The results were publicized in the final report.

The Results

During the game, attention was directed primarily towards the first goal (hospital members should become more aware of the problems) and, to a lesser degree, towards the second goal (exploring strategic challenges). Agreement about the problem was a necessary condition for the success of the concept of “medical professionals in the lead.” The game assignment had required them to make a plan for the strategic challenge presented in the scenario; this was used primarily to obtain a joint problem definition and secondly to give some insight into possible solutions.

With regard to the first goal, the game can be considered a success. This can be concluded from the debriefing and the questionnaires. In January 1998, a final report that contained conclusions by the participants and consultants was sent to the Board of Directors. Four important lessons can be distinguished:

• The Board of Directors should consult the division managers about strategic issues before establishing a policy framework;

• The division managers should consult each other more often about strategic issues;

• Ways need to be found to take advantage of the expertise of the nursing and financial managers for the formulation of the general hospital policy; and

• There is a need to pay attention to the essential role of the department heads and other executives in developing and implementing the general hospital policy.

The participants agreed about the overall value of the simulation, but when answering the question: “Did you learn anything?” they indicated that the upper hospital management had probably learned more than the participants themselves. This can be seen as a remarkable unanticipated result. During the game, top management paid little attention to the department heads (many of these players complained that they were bored and underused). In the evaluation, this led to the recommendation to involve them more intensively in the client’s policy cycle.

Case Two – Globalization and Pharmaceutical Research & Development

In this case, a large U.S.-based pharmaceutical company had developed the idea of starting an R&D facility in Europe. R&D management, whose task was to put this strategy into operation, had to address several important questions: Should we expand into Europe? If yes, what activities should we expand? Do we need to acquire new skills? Where should we locate these new activities? And, how should we best implement these plans?

They opted to use a policy exercise that required top management to explore the issues in a simulated environment as they thought through the implications. The result was unexpected, in that the leading option at the outset was rejected in favor of an alternative that was not articulated until the exercise was played. As a consequence, much smaller sums of money were put at risk and favorable results were achieved in a fraction of the time the initially favored option would have required.

This case is noteworthy because it was a good example of the game design process actually guiding the strategic debate. The project covered both the phases of strategic analysis and strategic choice. The participatory systems analysis proved vital for the proper framing of the problem. In this phase, it became clear that enormous sets of data had already been collected. The game design process helped the client to develop a format for analysis so that scattered data became real information. It proved essential to ensure that all the tacit knowledge of the relevant professional functions was used.

The Client

The client for this project was the pharmaceutical research and development division of a large international drug company. The company was faced with increasing problems in getting new products developed and to market. A multinational, publicly held corporation, the company had substantial existing foreign investments. In response to an expanding global awareness, they were concerned with remaining competitive in the rapidly changing pharmaceutical industry. To remain competitive, they had to adapt to a changing environment; it was essential for them to examine the corporate mission as it needed to change in the future. To achieve the goal of timely product introduction worldwide, thus increasing market share and profitability, it was felt within the company that its drug discovery and development effort had to be extended into new markets; the establishment of new foreign discovery capabilities was thought to be essential. A new R&D facility in Europe was believed to be their best option.

An earlier decision to expand in another country had not gone well. Analysis revealed that this was largely due to a failure to recognize the complexity of the decision environment and the importance of involving key personnel in the process. As a consequence of these difficulties, management resolved to use a process that would involve the appropriate people within the organization from the outset. Due to many uncertainties associated with this decision, they elected to use a policy exercise to help them decide on a specific location. The aim was to have a consensus-building activity that would draw upon the wisdom available within the organization.

The main decision under consideration concerned the expansion of pharmaceutical R&D facilities. Since the decision would impact on many facets of the corporation, the proposed European Discovery Facility (EDF) needed to be evaluated in terms of key endogenous and exogenous factors, with a future’s perspective in mind, as the 5-year, 10-year, and 25-year implications of any decision were investigated. At an operational level, they were concerned with how to implement the EDF to enhance the company’s long-run global posture.

The external considerations affecting their mission were:

• The state of the global economy;

• The public’s growing concern over the burden of healthcare costs;

• A shift in the provision of healthcare services from the expert to the concept of self-help;

• The possibility of reduced rates of return in the pharmaceutical industry;

• The prospects for supporting research and development with diminishing resources; and

• The increased significance of new product introduction in the pharmaceutical industry.

In response to these changes in the industry, they had to address a number of strategic and operational issues. Strategic issues that were considered included:

• Research and development productivity;

• The company’s foreign role;

• Internal standards and their application abroad;

• Enhancement of a global posture; and

• The strategic policy implications of a European Discovery Facility.

The Problem

In an effort to remain competitive in a rapidly changing international context, the company decided to seriously examine the pros and cons of locating a research facility in Europe. The problem was to identify all the significant variables, to delineate these variables in some clear format, and to analyze them to establish their relative priorities. All of this was accompanied by the need for participatory decision making and effective communication among the staff of the R&D Division, as well as with other divisions and upper management. In this particular case, the problem that was initially presented by the client was: “In which country should we locate this facility?” After a period of time, the question changed to four broad questions that addressed both strategic (what?) and operational (how?) considerations: Should we expand? If so, how should our capability be changed? Where should we locate? And, how can we bring this transformation about?

The 16 tasks given to the participants during the exercise were designed to help the R&D staff formulate an accurate and innovative conceptualization of the EDF problem. Participants in the process were asked to make a decision on questions centered on the following areas:

• Discovery and development emphasis;

• Research activity proposed for the EDF;

• Therapeutic/technical mix;

• Geographic location of the EDF;

• Structure and implementation of the EDF;

• Internal organization;

• Degree of home office involvement; and

• Staffing the EDF.

Goals, Purposes, and Objectives

The exercise was developed to aid top management in formulating and assessing their strategy. The explicit objectives were:

• To assist R&D management in the development of the parameters for the proposed research facility (location, style, capacity, configuration, and primary mission);

• To provide for participatory and interdisciplinary problem formulation and effective communication among the management team facing the decision;

• To help management of the R&D Division reach consensus on the optimum siting of a new facility in Europe, thus aiding the Office of the Chairman in reaching a decision; and

• To encourage the advancement of alternative approaches to research, thus helping to formulate an innovative conceptualization of the problem; and

• To transmit to appropriate staff the decision process as well as the dimensions of the problem that had to be considered in reaching a decision.

Why Did the Client Select the Policy Exercise Process?

In their attempt to deal with the problem, management selected the policy exercise methodology as the most appropriate one because of its ability to:

• Investigate the complexities of important, non-reversible decisions under conditions of uncertainty by identifying all the variables under consideration, delineating them in a clear format; and analyzing them by establishing relative priorities;

• Provide explanatory, if not predictive, insights about the problem and its environment to participants in the process;

• Overcome disciplinary, language and cultural barriers; facilitate communication in a situation where varied jargon was used; induce and evoke a high level of participation; and, allow participants of widely varying perspectives to gain a shared overview of the problem;

• Compress time, and when employed through several cycles representing defined time spans, enable the long-range outcomes of one or another course of action to become more comprehensible; and

• Augment the rational systems approach to problem solving by allowing infusion of subjective judgments into the process.

Specifications for Policy Exercise Design

The successful development of an exercise requires a careful delineation of responsibilities and lines of authority. These, and other appropriate administrative matters, must be fully resolved before the substantive material is addressed. In this case, it proved necessary to explain the approach to the central stakeholders. Although the technique is very old, its use in serious policy debates in large corporations is relatively new. Special attention on the part of the project team was required at this stage to legitimize the effort. The project team consisted of researchers from the University of Michigan, an internal (client) advisory committee and external consultants. The duration of the project was negotiated to be four months. It was important at the outset to define the criteria that would later serve as the measure for the evaluation of the product. The objective of the specifications was to raise and address specific questions that pertained to and anticipated the final conditions that would govern the design and use of the exercise. This is a natural extension of the problem statement, in which the objectives and constraints for assessment of design, construction and use are made explicit. In this particular case, the specifications included a definition of the intended audience, primary goals, stylistic considerations (reflective, mutual problem-solving style), and practical constraints: duration (one day), number of participants (12-18), computer usage, room and material requirements, and the planned recording of the participants’ responses.

The participants were drawn from the Research & Development, Control, International, Medical Affairs, Manufacturing, Regulatory Affairs, and Treasurer divisions. These participants were senior staff members who were asked to work from one of five “perspectives.” The perspectives did not coincide exactly with the position these participants held in real life; rather, they were an amalgamation of several executive responsibility areas. The players were selected on the basis of their familiarity with the actual role that was subsumed under that perspective.

The Schematic: A Model of Reality

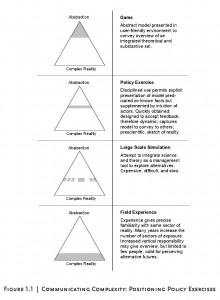

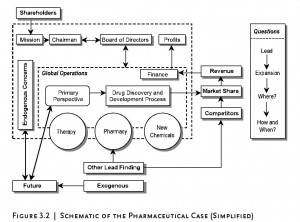

Several trial schematics preceded a final form for delivery to the client. This graphic had been reduced to those factors considered relevant within the constraints of the problem statement; this process of selection took place in the context of an ongoing dialogue with the client. The final document needed to retain enough detail to adequately represent the problem environment; however, it also needed to communicate the central aspects visually and quickly. It became an integral part of the exercise and provided the frame of reference for the policy exercise activity. A simplified version of the final schematic of the EDF problem environment is presented below in Figure 2.2 The schematic places the following elements in relation to each other:

• The primary stages of the drug development and drug discovery process;

• The interaction of this process with related exogenous processes (competition, universities, etc.);

• The primary in-house (endogenous) perspectives (medical, marketing, regulatory, management, manufacturing and science);

• The relationship of the discovery and development process with the rest of the company, the market and the company owners;

• A wide range of endogenous and exogenous concerns placing the discussion about the discovery facility against a 25-year time horizon; and

• The four central questions that the gaming exercise addressed: What was the future of the drug development and discovery process? What type of facility was required? Where should it be built? And, how can the plan be placed into operation?

Figure 2.2

The interactive development of the schematic was an important part of the process for the client who viewed this document as extremely valuable. The schematic was significant for the following reasons:

• It showed the client that the consulting team had reached a mature understanding of the problem and its environment; as such, it was an early step in the legitimization of the project;

• It served as a discussion vehicle because it forced the respondents who held different views on how the organization functioned to resolve those differences among themselves. Conflicting views of the “big picture” had to be integrated into this compromise view;

• It forced all the different stakeholders to look beyond the boundaries of their normal work environment and, in doing so, it established a sharp image of the problem; and

• It was a solid basis for the selection of the main topics to be addressed by the exercise.

The problem set, as initially perceived, was too broad to be included in the exercise. The factors of primary concern were identified based on the original problem statement and the specifications. The schematic proved very useful in the process of selecting components for inclusion in the exercise. The process guaranteed that the exercise met the primary criteria: it was situation specific, relevant and parsimonious.

The evolution of this schematic experienced a dramatic moment! It had been reviewed and approved by all senior staff except the Vice President of Sales (the design team had not been allowed to present the draft to Sales because “We create products; they sell them!”). After the schematic was finalized, the design team prevailed in getting access to the Vice President of Sales. He immediately recognized that the drawing was invalid in capturing the primary research flow process – it failed to illustrate products that were licensed at the several decision points in the development of a product. The schematic was redrawn and an intense debate followed; it was approved as modified. During the play of the game, this information proved decisive in rejecting the leading pre-game strategy and in the development of an unexpected (and successful) final strategy.

Description of the Policy Exercise

The EDF format employed participants playing roles that represented diverse perspectives on the problem. The exercise consisted of 16 tasks designed to help the R&D staff formulate an accurate and innovative conceptualization of the problem. The focus of attention was on the parameters of the primary mission (location, style, capacity, and final operational configuration). The overall purpose was to identify the R&D activities that would increase their ability to remain competitive over the next 20 years.

The scenario focused on the question: What should their strategy be to be successful in the 21st century? The scenario outlined a brief history of the corporation, the company’s mission, the pros and cons of a European Discovery Facility, and future considerations from a variety of perspectives (science, medicine, management, manufacturing, marketing, regulatory activities, international concerns, drug development, etc.). The scenario focused on the premise that the expansion of the research and discovery activities in Europe would:

• Contribute to their acceptance as an international pharmaceutical company;

• Increase scientific networking with the international academic community;

• Allow them to tap local and regional knowledge relevant to new drug discovery;

• Expand the pool of scientific talent that they could tap to fill critical staff positions;

• Improve their ability to develop drugs outside the U.S. regulatory climate;

• Accelerate the registration process in the region where the facilities were located;

• Allow for more effective capacity to respond to regional disease entities;

• Expand marketing potential outside the U.S.; and

• Inject fresh ideas and approaches into the thinking of the R&D organization.

During the course of the exercise, events were introduced to update the scenario; players were expected to evaluate the impact of these events on their decisions. The roles in the EDF exercise represented the key perspectives that influence the R&D process. The participants were asked to assume and represent the issues and concerns that would be particularly important for each perspective. Following are short role descriptions for each role.

• The Management Advocate Role was responsible for administrative efficiency; management style; personnel and staff development; finance, including budgeting; and efficient utilization of resources; and exogenous concerns such as economic conditions in the marketplace and communications.

• The Manufacturing Advocate Role dealt with equipment and technology requirements, production scheduling, development, feasibility, and efficiency; its exogenous concerns were new process technology developments, governmental standards and controls; and consumer safety.

• The Marketing Advocate Role had to think through strategies on product promotion and recognition, pricing, corporate image, product line; and analysis of domestic and international markets and distribution, market share, competition, and cultural sensitivity to therapeutic needs.

• The Medical Advocate Role was responsible for thinking through strategies that related to lead finding, therapeutic needs, new indicators, product introduction, drug development and testing technologies. Exogenous concerns included access to and strength of academic/clinical contacts, clinical support, journal publication, data transfer, and cultural sensitivity to therapeutic needs.

• The Regulatory Advocate Role was to create the strategies about internal control standards, licensing, and corporate liability. Exogenous concerns included country-specific drug registration, patent requirements, governmental standards/ controls, consumer safety, and political concerns.

• The Science Advocate Role focused on strategies that related to lead finding, pre-selection of new drugs, pharmaco-therapeutic concepts, new chemical entities, drug development, internal research environment and support, and research flexibility. Exogenous concerns were access to the scientific community, publication in journals, new drug development technologies, communication and data transfer networks, external lead finding, new chemical entities, pharmaco-therapeutic technologies and concepts.

The complex nature of the problem being addressed by the EDF exercise required that players have access to a wide variety of specific and factual information. As the exercise did not intend to make factual experts of the players, the majority of the information and data was presented as accessory material that was available for players to draw upon as the need arose. This information assisted players in realistically assuming and playing their roles. The data was made available through a number of formats including document files and abstracts, topic-specific notebooks, charts, and graphs.

The need for accessible information dictated a format that allowed for easy filing, storage, retrieval, and presentation of data essential to the decision-making process. The selected format made extensive use of graphic displays, indexed notebooks, and computerized database capabilities. The room layout and environment was similar to a war room model. Graphic displays were posted in ready view of all participants and additional information was easily accessed in the notebooks or from a computer. Trained staff was in the room to assist as required.