Will the Golden Age For Corporate Shareholders Ever End?

John P. Ruehl – Source: Independent Media Institute

05-05-2024 ~ Shareholders have assumed enormous influence over U.S. corporations over the last few decades. Despite their firm hold, shifts are underway that could alter the domestic corporate landscape.

On April 3, 2024, Disney CEO Bob Iger officially fended off the attempt by institutional investor Nelson Peltz and his hedge fund Trian Partners to secure two board seats. During the affair, Disney faced pressure from proxy advisory firm Institutional Shareholder Services to support Peltz’s initiative. While Iger prevailed, the costliest board fight in history underscores the significant influence of shareholders in shaping the fates of corporations.

Historically, U.S. corporate power was concentrated among executives, though with varying degrees of influence held by workers and other stakeholders. However, over the last century, U.S. corporations increasingly oriented themselves around their stock price and the imperative to maximize shareholder value. This mindset has now firmly entrenched itself within U.S. corporate culture and continues to shape their decisions and priorities.

Until the early 20th century, shareholders wielded minimal influence over U.S. corporations, with notable changes instigated by industries such as railroad conglomerates. To sidestep antitrust accusations and manipulate competition, for example, railroad companies created “communities of interest” by buying shares in one another, frequently installing their financiers and bankers on targeted companies’ boards. However, increased antitrust enforcement from the Supreme Court discouraged these practices by 1912.

Investors remained undeterred. Throughout the 1920s Merger Wave, shareholders amassed large stakes in various companies, eroding the traditional influence of company founders, executives, families, as well as other stakeholders like employees, trade unions, suppliers, customers, and local communities. The momentum of the shareholder rights movement surged following the stock market crash in 1929, which prompted legislation aimed at increasing transparency granting shareholders increased authority and information access.

During World War II, U.S. industrial power was centralized under government control. This trend, however, waned after the conflict concluded, leading to a resurgence of privatization that benefited shareholders as control shifted away from government oversight. Despite initially dominating the post-WWII economic landscape, U.S. companies began encountering tougher competition from global rivals by the 1960s, hindering their growth.

During the 1970s, prioritizing stock price growth for shareholders gained traction. However, it was the 1980s when this mindset became institutionalized, with legal rulings such as Smith v. Van Gorkom, (1985) and Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews and Forbes Holding, Inc. (1986) affirming corporations’ duties to shareholders.

Amendments to corporate laws aimed to enhance shareholder rights, enabling actions like director nominations, and voting on executive pay. Executive stock rewards thus began to increase, incentivizing risk-taking for short-term gains. Additionally, the 1986 Tax Reform Law cut the individual top tax rate and fueled heightened interest in short-term stock trading.

The evolution of institutional investors also played a pivotal part in reshaping the financial landscape. The growing role of hedge funds, 401(k) pension plans managed through mutual funds, and the introduction of other major asset management firms like Vanguard and BlackRock began to herald a new era in the stock market and corporate governance.

In the decades up to the 1980s, corporate raiding had become increasingly common. However, regulatory changes during the 1980s lifted restrictions on mergers and acquisitions, leading to the peak of the U.S. corporate raiding era. During this time, riskier, higher-return bonds called “junk bonds” and leveraged buyouts involving a large amount of borrowed money to purchase a company evolved into crucial financial tools for funding corporate takeovers. Companies often targeted struggling companies or undervalued firms, acquiring them with the intention of privatizing operations, slashing costs, divesting assets, and eventually reintroducing them to the public market.

In response to these attempts, entrenched corporate management networks implemented defensive strategies. They issued new shares to existing shareholders as poison pills, diluting the ownership stake of prospective buyers. Dual-class share structures allowed company insiders to maintain their control even with a minority of shares. Staggered boards meanwhile divided boards into different classes to make it difficult for outside entities to gain control. However, many still found themselves compelled to yield to the demands of institutional investors.

While corporate raiding declined in the early 1990s, the concept of stock prices as the primary measure of a company’s performance, thereby ensuring shareholder loyalty, was established. With more individuals and pension funds investing in the stock market, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average becoming an even more important economic indicator, increasing shareholder value had become the prevailing corporate imperative by the close of the 20th century.

Criticism of the shareholder value system and its repercussions, such as job outsourcing and soaring CEO pay, continued into the 2000s and remains widespread. Boeing’s diversion of pandemic relief funds for stock buybacks highlights the issue of prioritizing immediate shareholder gains over long-term stability and growth.

Boeing’s actions, though legal due to a 1982 SEC ruling that legitimized buybacks, received public criticism without significant consequences. Nevertheless, Boeing’s ongoing troubles with the safety of its planes have been exacerbated by the lack of investment. Several incidents have led to a notable decline in its share price over the last few months, erasing the benefits achieved through short-termism policies.

The evolution of corporate culture toward shareholders has occurred globally but to a lesser extent in other capitalist countries. In South Korea and Japan, stakeholder consensus among customers, suppliers, and the community remains more prominent. Long-term relationships are common with employees and suppliers, facilitating trust and collaboration throughout the supply chain, though efforts to increase the influence of shareholders are ongoing.

Many European firms have traditionally been characterized by high levels of ownership by founding families and governments. While this has slowly changed, there remains a culture of “codetermination” in Germany and other European Union (EU) countries. This model grants greater rights to employees in the decision-making process, with a focus on stability and job preservation, and returned after Germany pursued more shareholder-friendly policies during the 1990s.

In contrast, the UK shares a corporate structure more akin to that of the U.S., and it remains Europe’s financial powerhouse even after Brexit. However, the UK only has 15 companies in the top 100 companies, compared to 27 for Germany, 31 for France, and 40 for Japan in 2023. China’s state-owned enterprises have meanwhile claimed the top spot from the U.S.

Nonetheless, advocates of U.S. corporate structure highlight the flexibility and adaptiveness of U.S. companies compared to European and Asian firms, which are often viewed as less innovative. Additionally, they contend that this system has contributed to higher GDP growth than other developed countries, while several EU states maintain high unemployment rates. It is also argued that U.S. companies have navigated recent challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine better.

U.S. companies have of course benefited from various factors such as the size of the domestic market, geopolitical influence, and status of the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency, attracting global investment. However, they have become enamored by short-termism driven by investors. By 2020, the average holding period of shares on the New York Stock Exchange had shrunk to roughly five months, compared to an average of eight years in the late 1950s. Shareholders can easily sell their shares without sacrificing any assets in the company, hindering long-term strategic planning.

Frustration with the persistent dominance of shareholders in the U.S. corporate world has prompted efforts to diminish their influence in recent years. In 2018, Democratic senators proposed the Reward Work Act and the Accountable Capitalism Act, which would require large companies to allocate 33 to 40 percent of board seats to worker-elected representatives. These proposals mirror the German concept of board-level codetermination, adopted in the post-WWII era and now popular in many European countries.

Some contend that the German-style codetermination model is a poor fit for U.S. corporations. Moreover, codetermination initiatives have primarily focused on facilitating discussions between workers and employers on immediate conditions, serving as a supplement to existing union representation and collective bargaining structures rather than radically strengthening worker influence.

One advantage is the flexibility granted by U.S. state law, enabling states to experiment with their own rules. On April 19, 2024, the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, voted to unionize after two failed attempts in 2014 and 2019. The decision not only brings representation to Volkswagen workers in the U.S. but also represents the first successful unionization effort at a non-Big Three (General Motors, Stellantis, and Ford Motor Company) auto plant in the South. And since the first unionization push in New York in 2021, 41 states now have at least one unionized Starbucks, reminiscent of a century ago when labor movements gained significant momentum.

Policy recommendations have also emerged. Corporate Social Responsibility emerged originally in the mid-20th century but then reemerged by the turn of the millennium. Environmental, Social, and Governance considerations then emerged by the 2010s, alongside Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives. At a 2019 American Business Roundtable resolution, 196 CEOs advocated for a change in business culture and to commit CEOs to “meeting the needs of all stakeholders.”

Despite increasing calls for corporate accountability, these endeavors often lacked enforceability. DEI initiatives in particular have become embroiled in political controversies, leading to companies backtracking on their commitments. Shell meanwhile faced pressure from activist shareholders in 2021 regarding its contributions to climate change, including from its largest institutional investors, Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street. But as economic considerations took precedence, minimal pressure was put on Shell, resulting in negligible advancements in climate change initiatives.

Nonetheless, just as the rise of communication networks in the 20th century allowed investors to gain influence over corporations, the rise of the internet and social media has equipped stakeholders and grassroots activists with their own tools. Public pressure to raise the minimum wage has resulted in dozens of cities and counties increasing their minimum wage in recent years and compelled companies like McDonald’s to stop lobbying against it. The GameStop stock saga of early 2021 meanwhile demonstrated how retail investors, fueled by social media hype, drove the company’s stock price upward, threatening institutional investors by disrupting established market dynamics.

Institutional investors like Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street, which all own major shares in one another, have helped lead to an immense concentration of corporate ownership. Failing to reduce their dominance, and shareholders in general, could inspire further reforms. Limited Liability Companies emerged partly in response to this dominance, with the first one established in Wyoming in 1977. Meanwhile, large companies like OpenAI and Stripe are opting to remain private, further reducing the power of shareholders.

Additionally, worker cooperatives, businesses owned and operated by employees who share in decision-making and profits, have experienced renewed interest in the U.S. Despite waning popularity after their initial rise in the 19th century, they began to rebound in the 1970s and 1980s. The founding of the United Stated Federation of Worker Cooperatives in 2004 has since helped expand the number of worker cooperatives in the country.

Benefit corporations, for-profit companies that prioritize both their societal and environmental impacts, have also seen significant growth in recent years. Maryland became the first U.S. state to enact laws providing for public benefit corporations in 2010, and has since been joined by 36 other states and Washington, D.C.

The corporate era preceding the current one characterized by shareholder dominance was far from ideal. However, to foster a more equitable corporate landscape, public support for political initiatives that challenge the status quo and multi-stakeholder-focused business initiatives will be crucial to reducing the influence of shareholders. This may lead to major upheavals in pension systems and 401(k) plans invested in the stock market, yet it holds the potential to greatly improve worker rights, inspire long-term strategic planning, and promote a more equal distribution of corporate profits.

By John P. Ruehl

Author Bio: John P. Ruehl is an Australian-American journalist living in Washington, D.C., and a world affairs correspondent for the Independent Media Institute. He is a contributing editor to Strategic Policy and a contributor to several other foreign affairs publications. His book, Budget Superpower: How Russia Challenges the West With an Economy Smaller Than Texas’, was published in December 2022.

Credit Line: This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

05-03-2024 ~ Extensive ocher use reflects the culture and cognitive abilities of early humans, who inherited an affinity for red from primate ancestors.

05-03-2024 ~ Extensive ocher use reflects the culture and cognitive abilities of early humans, who inherited an affinity for red from primate ancestors. 05-03-2024 ~The Netherlands commemorates the victims of the Second World War annually on May 4th. This remembrance takes place through a ceremony held at the central square ‘de Dam’ in Amsterdam.

05-03-2024 ~The Netherlands commemorates the victims of the Second World War annually on May 4th. This remembrance takes place through a ceremony held at the central square ‘de Dam’ in Amsterdam.

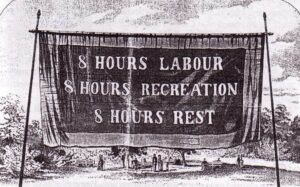

05-01-2024 ~ Progressive economic ideas have been on the whole an anathema to the U.S. political establishment and violence against labor militancy has always been the norm for almost all of the country’s political history. Nonetheless, the U.S. labor movement has not yet been defeated.

05-01-2024 ~ Progressive economic ideas have been on the whole an anathema to the U.S. political establishment and violence against labor militancy has always been the norm for almost all of the country’s political history. Nonetheless, the U.S. labor movement has not yet been defeated.