Censuur en zelfcensuur in de klassieke islamitische wereld

‘Verbrand rustig papier, want wat u daar leest

zit veilig opgeborgen in mijn geest

Het gaat met me mee, waarheen ik ook rijd,

staat stil als ik stop en sterft als ik overlijd

Zwijg over ‘t branden van papier en perkament;

zeg wat u weet, en men zal zien dat u verstandig bent’

(Ibn Hazm)

De Spaans-Arabische denker Ibn Hazm (Cordoba 994 – Niebla 1064) leeft in de westerse wereld voort door de ‘Ring van de duif’, een jeugdwerk vol melancholieke en misschien ook wel vroegwijze bespiegelingen over de liefde. Het boek is in vele talen vertaald, onder andere in het Nederlands in een vertaling van Remke Kruk en J.J. Witkam (Amsterdam, Meulenhoff, 1977, 2e dr. 1985). De islamitische wereld kent hem echter vooral als schriftgeleerde en grondlegger van een eigen islamitische rechtsschool. Hij was een moeilijk mens, buitengewoon onbuigzaam en principevast, en hij had daarnaast de gewoonte vrijelijk zijn mening te geven. Hij was voortdurend in conflicten verwikkeld met de schriftgeleerden van de gevestigde Malikitische rechtsschool, die hij als meelopers van het gezag beschouwde. In politiek opzicht was hij loyaal aan het Umayyadenkalifaat van Cordoba, hoewel dat tijdens zijn leven ter ziele ging en opgevolgd werd door een aantal lokale dynastieën die in het Spaans bekend staan als de ‘Reyes de Taifas,’ partijkoningen. Hij kwam in aanvaring met de machthebber van Sevilla door hem in een van zijn boeken te ontmaskeren als een fraudeur en een moordenaar. Het was deze zelfde heerser die op gegeven moment de opdracht gaf om zijn boeken publiekelijk te verbranden, waarop Ibn Hazm de bovengenoemde dichtregels schreef (Asín Palacios 1927-32, I, p. 230-235). In het gedicht lijkt hij het incident te willen bagatelliseren omdat alleen de papieren dragers van zijn gedachten vernietigd worden, niet de geest die deze gedachten heeft geproduceerd. Dat komt wat naïef over, omdat hij niet lijkt te beseffen dat het papier wel degelijk essentieel is om zijn gedachten te kunnen verbreiden, en verbreiding van zijn gedachten is wat elke auteur tenslotte wil.

Dit voorval illustreert het aloude spanningsveld tussen de behoefte van de individuele burger om zijn mond open te doen en het belang van de samenleving als geheel. Dit belang bestaat uit twee elementen, het morele belang van de openbare zeden en het politieke belang van de openbare orde. In vrijwel alle samenlevingen zijn het de geestelijke en wereldlijke autoriteiten die over dit tweeledige belang waken. In het Westen hadden we, vooral sinds de uitvinding van de drukpers, het instituut van de censuur, uitgeoefend door Staat of Kerk. Deze censuur moest noodzakelijkerwijs op strakke, ambtelijke wijze georganiseerd worden. De drukpers gaf de mogelijkheid om zeer snel en op grote schaal ideeën te verspreiden, en er moest dus slagvaardig worden opgetreden om de verspreiding van ongewenste ideeën te voorkomen. In de periode daarvoor, toen boeken nog moeizaam met de hand gekopieerd moesten worden, ging de verspreiding van teksten veel minder snel en waren er minder schrijvers en minder lezers. Beide laatste categorieën behoorden daarenboven tot de sociale laag die het dichtst bij het officiële gezag stond. Dat betekende dat de controle over het geschreven woord makkelijker uitvoerbaar was en dat er dus geen grote organisatie of ingewikkelde regelgeving nodig was om die controle te realiseren.

De uitvinding van de boekdrukkunst mag dan gelden als beginpunt van de censuur als ambtelijke instelling, maar dat betekent nog niet dat er daarvoor in het Westen geen samenhangende pogingen werden ondernomen om het geschreven woord te controleren. Zo woedde er in de dertiende eeuw aan de universiteit van Parijs een debat over de verhouding tussen de christelijke orthodoxie en de filosofie van Aristoteles en diens Arabische commentatoren, zoals Averroës. In 1210 en 1215 werden de ‘Arabische commentatoren’ verboden, in 1231 werden ze gecensureerd toegelaten en in 1255 werden ze officieel aan het curriculum toegevoegd. Uiteindelijk stelde Étienne Tempier, bisschop van Parijs, in 1277 een lijst van verboden opvattingen op. Ieder die bijvoorbeeld de opvatting verkondigde dat de wereld eeuwigdurend was of dat God niet rechtstreeks kon ingrijpen in de gebeurtenissen op aarde kon rekenen op excommunicatie (Wilson 1996, II, p. 1017-1018, Piché 1999, p. 160).

De ‘klassieke’ islamitische samenleving en de burgerlijke vrijheden

De controle op het geschreven woord en de inperking van de menings-vrijheid van het individu zijn vrijwel altijd gangbaar in samenlevingen die het collectieve belang stellen boven het individuele belang. Samenlevingen die van dit model uitgaan stellen ook nog vaak een eind-doel aan de samenleving, een politieke of godsdienstige vervolmaking. Het ligt dus voor de hand dat individuen die doelbewust dit streven saboteren geneutraliseerd moeten worden. Deze gedachte wordt treffend verwoord door de vierde editie van de Duitse ‘Grosse Herder’ encyclopedie, die gedeeltelijk tijdens de Hitlerperiode verscheen:

‘Im nationalsozialist[ischen] Staat ist die Meinungsfreiheit des Einzelnen ersetzt durch das Recht der Volksgemeinschaft, alle volksfeindl[iche] Kräfte fernzuhalten.’ (‘Der Grosse Herder’ 1931-1935, lemma ‘Zensur,’ XII, kol. 1445-46)

In tegenstelling tot de sterk geïndividualiseerde, moderne westerse maatschappij geldt de islamitische samenleving als een collectief met religieus geïnspireerde doelstellingen, waarbij het belang van het individu ondergeschikt is aan het groepsbelang of de heilsverwachting van de groep als geheel. Dit is vanzelfsprekend een generalisatie, want het gaat hier om een enorm groot en divers gebied met een geschiedenis van bijna veertienhonderd jaar. Het beeld wordt in ieder geval bevestigd door een interview van Elma Drayer in het dagblad Trouw van 6 april 2001. Hierin omschreef arabist/diplomaat Marcel Kurpershoek de samenleving in Saoedi-Arabië als volgt:

‘Bij ons [in Nederland] zijn individualisme, experimenteren, zelf iets nieuws bedenken, de hoogste waarden. In Saoedi-Arabië is het omgekeerd. Daar heerst een sterke drang tot conformisme. Ze lopen allemaal in dezelfde, zakachtige gewaden, dragen dezelfde hoofd-doeken. En het is heel verkeerd om in je eentje te geloven.’

Nu heeft Kurpershoek het hier over het moderne Saoedi-Arabië, maar voor dit land geldt dat het zich meer dan andere islamitische landen vastklampt aan de oude waarden van de klassieke islamitische samenleving. Deze klassieke samenleving, die min of meer intact bleef tot aan de komst van het Europese kolonialisme in de negentiende eeuw, leek nog het meest op de westerse middeleeuwse standenmaatschappij. Alle macht kwam van God en de machthebber was diens plaatsvervanger op aarde, of zoals de Osmaans-Turkse sultans zichzelf noemden, ‘Gods schaduw op aarde’. Het geldend recht was gebaseerd op de onaantastbare en onveranderlijke, en vooral ook onfeilbare Goddelijke Openbaring. Als iedereen zich maar aan deze wet hield zou de volmaakte samenleving vanzelf tot stand komen, net als in de dagen dat de profeet Mohammed zelf nog de scepter zwaaide over zijn kleine groepje geloofsgenoten. Het was aan de machthebber om gehoorzaamheid aan deze wet af te dwingen, en hij werd daarbij ter zijde gestaan door drie groepen: het leger, dat de orde met geweld beschermde, de klasse van religieuze schriftgeleerden, die de heilige wet interpreteerden en toepasten, en tenslotte het administratieve overheidsapparaat. De kringen aan het hof, de schriftgeleerden en de ambtenaren vormden de klasse van geletterden, de makers en lezers van teksten. Verder was er natuurlijk het gewone volk, vaak als de ‘kudde’ aangeduid. Deze kudde was onderverdeeld in vrijen en slaven. Het concept ‘vrijheid’ (in het Arabisch: ‘hurriyya’) werd dan ook in die termen gedefinieerd: een vrije = geen slaaf. Hoewel de ene onderdaan meer geprivilegieerd was en meer macht en geld kon hebben dan de andere kon uiteindelijk niemand rechten doen gelden tegenover het overheidsgezag, of zoals de Amerikaanse oriëntalist Franz Rosenthal het zegt:

‘The greatest threat to individual freedom resulted from the fact that the government – that is, the ruler in actual possession of the power – had the right to exercise judicial power in most cases concerning public order and safety. The ruler also had the right to imprison people at will whenever he decided that it was necessary to do so. That this was his right cannot be denied. It followed from the fact that in Islam, the ruler had jurisdiction over the whole vast area not covered by the religious law […] The govern-ment would send to prison actual or alleged heretics, religious fanatics who took the law into their own hands, charlatans, and, in general, all those

guilty of violating public order in any one of countless ways.’

(Rosenthal 1960, p. 53-54)

Dat wil niet zeggen dat er op basis van volstrekte willekeur geregeerd werd. Voor het duurzaam handhaven van gezag is legitimiteit nodig, en de vorst ontleende deze aan de godsdienst en de heilige wet. Bij het uitoefenen van zijn gezag moest hij dus bij voorkeur handelen in de geest van die wet. De toepassing en de interpretatie van de islamitische wet waren voorbehouden aan de klasse van schriftgeleerden. Binnen die klasse bestond er ruimte voor de uitwisseling van ideeën, en bij het ontbreken van een officieel leergezag zoals in het christelijke Westen konden tegenstrijdige opinies vaak naast elkaar bestaan. Dat klinkt in theorie mooier dan het in de praktijk was: in de loop der eeuwen consolideerde de orthodoxie zich en konden alleen zeer grote geesten zich werkelijk afwijkende opinies veroorloven, die vervolgens de nieuwe orthodoxe opvatting vormden.

Degenen die het te bont maakten in hun opvattingen over het geloof of de religieuze wet wachtte in laatste instantie een aanklacht wegens ketterij, een middel dat met enige spaarzaamheid gebruikt werd. Bij ketterverklaringen vonden wereldlijke en geestelijke autoriteiten elkaar moeiteloos, omdat de religieuze legitimering niet in het geding was en de wereldlijke overheid dus zonder terughoudendheid kon optreden. Het was een vonnis dat bijvoorbeeld prominente soefi’s trof, islamitische mystici. Soefi’s bestonden in alle soorten en maten, van in zichzelf gekeerde asceten tot losgeslagen figuren die beweerden dat zij God zo dicht genaderd waren dat de islamitische wet voor hen niet gold, een opinie met duidelijke gevolgen voor de openbare orde. Een dergelijk vonnis trof de mysticus al-Hallaj in het jaar 922, omdat hij zozeer geloofde in de versmelting van zijn persoon met het Goddelijke dat hij gezegd zou hebben: ‘Ik ben de Waarheid.’ Het technische detail dat hem fataal werd was zijn verklaring dat een gelovige ook de pelgrimstocht zou kunnen maken naar een bij hem thuis geconstrueerde Kaäba, zodat hij zich de reis naar Mekka zou kunnen besparen: een overduidelijk ketters standpunt. De kalief wist na veel discussie een ketterverklaring aan de schriftgeleerden te ontfutselen en al-Hallaj werd ter dood veroordeeld. Hij kreeg duizend zweepslagen, zijn handen en voeten werden afgehakt en men liet hem ‘s nachts aan een kruis hangen. De volgende dag werd hij onthoofd en werd zijn lijk verbrand (Kritzeck 1964, p. 112-113). Het is begrijpelijk dat onder deze omstandigheden de meer exuberante opvattingen niet lang overleefden. De drang tot conformisme en zelfregulering was sterk.

Deze bovenstaande kwestie viel binnen het domein van de isla-mitische wet, maar de schriftgeleerden probeerden ook hun invloed te laten gelden op het terrein dat Rosenthal omschreef als ‘the whole vast area not covered by the religious law’ (zie hierboven). De jurist al-Mawardi (974-1058) schreef een handboek over bestuurskunde, getiteld ‘Al-Ahkam al-sultaniyya’ (‘De vorstelijke decreten’), waarin hij het gedrag van de wereldlijke overheid zo veel mogelijk koppelde aan de koran en de islamitische wet (Al-Mawardi 1996). Ook hoge ambtenaren lieten met regelmaat een soort traktaten het daglicht zien dat wij in het Westen herkennen als ‘vorstenspiegels’: geschriften waarin auteurs zich uiten over de meest wenselijke bestuursvorm en het ideale gedrag van de vorst.

De islamitische schriftgeleerden probeerden zich als hoeders van de moraal ook te bemoeien met teksten die weinig met de islam van doen hadden, zoals poëzie en verhalend proza. Waren deze frivoliteiten wel toelaatbaar? Is het volgens de islam wel geoorloofd om dingen op te schrijven die niet echt gebeurd zijn of die niet echt gebeurd kúnnen zijn zoals fabels, waarin immers pratende dieren worden opgevoerd? De Nederlandse arabist Bonebakker ziet in principe een negatieve grondhouding van de islamitische geleerden tegenover literaire teksten, zonder overigens tot harde conclusies te komen (Bonebakker 1992, passim). Een dergelijke houding lijkt van alle tijden en van alle religies te zijn: in Nederlandse evangelische boekhandels zal men ook weinig fictie aantreffen, en in het moderne Midden-Oosten zijn het vooral de seculier ingestelde boekhandelaren die dichtbundels en romans verkopen.

Anders dan bij ketterij schoot de islamitische wet te kort bij het aanpakken van lasterlijke of obscene teksten. Vooral waar het ging om de seksuele moraal konden de juristen weinig kanten op: de islamitische wet respecteert in principe alles wat zich binnen de vier muren van het huis afspeelt, en het bekende koranvers ‘Uw vrouwen zijn een akker voor u, zo komt dan tot uw akker zoals gij maar wilt…’ (koran 2:223), gaf nauwelijks een handvat om een bepaald seksueel gedrag op te leggen. De islamitische wet verbiedt wel uitdrukkelijk seksuele handelingen tussen mannen en vrouwen die niet met elkaar gehuwd zijn of die niet in een meester-slavin verhouding tot elkaar staan, maar verder is het allemaal nogal ongewis. Daarnaast weet de islamitische wet in al zijn formalisme geen raad met het schrijven over verwerpelijke of verboden handelingen. Om een voorbeeld te geven: als Hasan overspel pleegt onder de ogen van vier, meerderjarige mannelijke getuigen, dan is hij zonder meer strafbaar. Als Hasan echter een boek schrijft waarin hij zegt: ‘Er was eens een man die overspel pleegde,’ dan is daar vanuit juridisch standpunt weinig tegen te doen. Het wordt echter weer een heel andere zaak als Hasan schrijft dat overspel uitdrukkelijk toelaatbaar is, want dan ontkent hij een bestaande islamitische rechtsregel en dat betekent ketterij.

Zelfcensuur

Buiten het gebied van het islamitisch recht had de wereldlijke overheid dus een grote vrijheid van handelen om op te treden tegen lasterlijke, obscene of zo maar onwelgevallige teksten van welk genre dan ook, fictie of geen fictie. Dat er in de klassieke wereld van de islam schrijvers waren die dat soort teksten maakten kan men duidelijk genoeg zien aan het voorbeeld van de recalcitrante Ibn Hazm. Schrijvers wisten dat er grenzen waren die niet overschreden mochten worden, maar waar die grenzen lagen moet van periode tot periode en van plaats tot plaats verschild hebben. Ook is hierboven al even aangestipt dat eigenlijk niemand rechten kon doen gelden tegenover de overheid, maar dat er toch verschillen waren in privileges en macht. Zo was de meest obscene dichter van de Arabische literatuur, Ibn al-Hajjaj (gestorven in 1001), tegelijkertijd als ambtenaar verantwoordelijk voor de handhaving van de goede zeden in Bagdad. De Nederlandse arabist Geert Jan van Gelder noemt dit verschijnsel een voorbeeld van een inconsequentheid die hij ook tegenkomt bij bloemlezers die zich druk maken over vieze gedichten, maar tegelijkertijd die gedichten citeren in hun bundels (Van Gelder 1988, p. 81-82), maar je kunt het misschien ook anders zien: door zijn sociale positie en zijn functie kon hij het zich wellicht veroorloven om obscene teksten te schrijven en te verspreiden, omdat hij in dit geval zelf de overheid vertegenwoordigde en dus een zekere onaantastbaarheid genoot.

Een schrijver die niet in zo’n benijdenwaardige positie verkeerde kon verschillende dingen doen om een aanvaring met de autoriteiten te voorkomen. Hij kon bijvoorbeeld zijn hart luchten en vervolgens de benen nemen. Zowel in politiek als in ideologisch opzicht is de islamitische wereld nooit iets anders dan een lappendeken geweest, en veel schrijvers vonden wel ergens een heerser die met hun opvattingen kon leven. Deze ‘intellectuele ballingschap’ klinkt dramatischer dan het in werkelijkheid was. Intellectuelen hadden voor hun levensonderhoud vaak een patroon nodig, en het eindeloos rondreizen ‘op zoek naar kennis’ was een universele islamitische traditie waaraan velen van naam meededen, op zoek naar teksten, collega-geleerden of een beschermheer (Sourdel 1985, p. 126-127).

Zover hoefde het natuurlijk niet te komen. Als een auteur een boek maakte kon hij van verschillende strategieën gebruik maken om te zeggen wat hij wilde, maar tegelijkertijd negatieve reacties op zijn tekst te voorkomen of te verzachten. We zouden dat nu zelfcensuur noemen. Nu is het in de regel erg lastig om uit te maken wat een auteur in zijn tekst heeft veranderd of aangepast onder druk van zijn omgeving, de autoriteiten of wat dan ook. Het enige wat we hebben is de tekst zelf, en wie probeert uit te maken wat de tekst had kunnen zijn in de beste van alle mogelijke werelden verzeilt al gauw in speculaties. Nu zijn er rondom de ‘eigenlijke tekst,’ zoals in voor- en nawoorden en ook wel in het gedrag van de auteur ten opzichte van zijn eigen tekst, wel momenten waar te nemen waarop de auteur gepoogd heeft eventuele negatieve reacties vóór te zijn.

Disclaimers en verontschuldigingen

Zo kan de auteur bijvoorbeeld een ‘disclaimer’ aan zijn tekst toevoegen of zijn verontschuldigingen aanbieden. De auteur verklaart dat hij de inhoud van zijn tekst zelf verwerpt of niet serieus neemt: hij heeft het boek alleen maar geschreven om mensen te waarschuwen. Zo’n disclaimer vinden we in het prozawerk van de Arabische auteur al-Hariri (gestorven in 1122). In zijn – puur fictieve – tekst biedt hij uitgebreid verontschuldigingen aan voor het feit dat zijn verhalen niet echt gebeurd zijn, maar dat zijn bedoeling niets anders is dan lering, niet frivool vermaak. Wordt volgens de islamitische wet iemand niet op zijn bedoelingen beoordeeld? Al-Hariri aarzelt niet om zijn eigen werk als nonsens te betitelen om eventuele kritiek te pareren (Bonebakker 1992, p. 7).

Een ander aardig voorbeeld van een verontschuldiging voor een tekst die mogelijk als aanstootgevend beschouwd zou kunnen worden is het boek ‘De verkwikking van de ziel, of wat de zuurpruim aan het lachen maakt,’ een vreemde verzameling van humoristische gedichten en verhaaltjes over eten en drinken, hasjiesj en feestvieren, gemaakt door de Egyptische auteur ‘Ali Ibn Sudun (1407-1464). In deze tekst staat een verhaal waarin de hoofdpersoon een bidkleedje steelt van een vrome man en vervolgens het kleedje verpatst om er hasjiesj van te kopen. Stelen mag natuurlijk niet en al helemaal niet van een vrome bidder, en het kopen van hasj is ook niet in de haak. Het is zeker niet het enige fragment waarin dingen gebeuren die God verboden heeft, en in het colofon staat dan ook een rijmpje waarin de auteur nederig boete doet voor wat hij geschreven heeft:

‘Als ik in mijn overdrijving te ver ben gegaan

en niets wat ik maakte de toets der kritiek doorstaat,

dan smeek ik de goede God dat Hij vergeeft wat ik heb gedaan,

in het volle besef dat Hij geen smekeling vallen laat’

(Vrolijk 1998, p. 175 Arabic text)

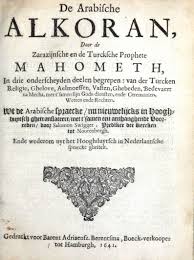

Ook in de Westerse oriëntalistische traditie komen deze disclaimers voor. Zo is er een Nederlandstalige versie van een Duitse vertaling van de koran, verschenen in 1641 onder de titel ‘De Arabische Alkoran door de Zarazijnsche en de Turcksche Prophete Mahometh… uyt de Arabische sprake nu nieuwelijcks int Hoochduytsch getranslateert … door Salomon Swigger … ende nu wederom uyt de Hoogduy[t]sche in onse Nederlantsche spraecke overgheset.’ De (overigens onbekende) Nederlandse vertaler onderkende het risico dat hij kritiek over zich heen zou kunnen krijgen bij het publiceren van een dergelijke onchristelijke tekst, en hij voorzag zijn boek van het volgende ‘ten geleide’:

Ook in de Westerse oriëntalistische traditie komen deze disclaimers voor. Zo is er een Nederlandstalige versie van een Duitse vertaling van de koran, verschenen in 1641 onder de titel ‘De Arabische Alkoran door de Zarazijnsche en de Turcksche Prophete Mahometh… uyt de Arabische sprake nu nieuwelijcks int Hoochduytsch getranslateert … door Salomon Swigger … ende nu wederom uyt de Hoogduy[t]sche in onse Nederlantsche spraecke overgheset.’ De (overigens onbekende) Nederlandse vertaler onderkende het risico dat hij kritiek over zich heen zou kunnen krijgen bij het publiceren van een dergelijke onchristelijke tekst, en hij voorzag zijn boek van het volgende ‘ten geleide’:

‘De Arabische translateur tot den Leser.

Hier uyt kont ghy verstaen ende vernemen, wanneer ende van waer haer valsche Prophete Mahometh zijnen oorspronck ende begin genomen heeft, ende met wat ghelegenheyt die selve dit sijn fabelwerck, lacherlicke ende dwaesachtige leere ghedicht ende ghevonden heeft: want hier in vindt ghy van alle sijn Droomen,

listen ende practijcken, ende alle sijn verleydische menschen-vonden.’

(Swigger 1641, p. [ii])

Anonimiteit

Een ander middel voor een auteur om zijn ideeën te verspreiden zonder persoonlijk erop aangesproken te worden is de anonimiteit. De tiende-eeuwse secretaris, hoveling en schrijver Abu Hayyan al-Tawhidi schreef het volgende over het ‘Genootschap van de Zuivere Broeders,’ een auteurscollectief dat een verzameling traktaten uitbracht over de gewenste vereniging tussen het islamitische geloof en de filosofie:

‘They claimed that perfection is achieved when Greek philosophy and the Arab religious law are combined. And they composed fifty epistles on all parts of philosophy, theoretical and practical, and made a special index for them. They called them The Epistles of the Sincere Brethren and Loyal Friends. Remaining anonymous, they distributed them among the bookdealers…’

(Kraemer 1986, p. 169)

Verbranding van eigen boeken

Franz Rosenthal noemt in een recentere publicatie het verhaal van auteurs die er voor kozen om hun eigen boeken te verbranden, vaak aan het eind van hun leven. Hij vermoedt dat het hier om een ‘topos’ gaat, een vaste wending zonder feitelijke betekenis. In alle door hem gesignaleerde gevallen ging het namelijk om buitengewoon vrome mannen, die tot deze daad kwamen vanuit een gevoel van zelfreiniging of het achterlaten van alle aardse beslommeringen. Misschien waren ze ook bezorgd over hun reputatie na hun dood en pasten ze een preventieve censuur toe op hun eigen werk (Rosenthal 1995, p. 40-42).

Verschuilen achter God en de autoriteiten

Het is de gewoonte in islamitische boeken om te beginnen met een lofprijzing van God en Zijn profeet. Soms is die heel kort, maar vaak worden de loftuitingen omgewerkt tot een soort kapstok, waarbij men de eigen motieven om een boek te schrijven rechtstreeks aan God zelf ophangt. Men verschuilt zich als het ware achter Gods brede rug. Dat kan heel onschuldig zijn, zoals in het monumentale verslag van de wereldreizen van Ibn Battuta (gestorven in 1368), waarin God degene is die ‘de aarde heeft onderworpen aan Zijn dienaren, opdat ze over haar wegen kunnen trekken,’ en die de kamelen en de boten geschapen heeft (Ibn Battoeta 1997, p. 7-8), en op de eerste pagina van het bestuurskundeboek van al-Mawardi wordt God geprezen als degene die recht en wet geschapen heeft zodat Zijn dienaren op de juiste wijze bestuurd kunnen worden.

In een wat minder onschuldige variant verwijst de Egyptenaar ‘Ali Ibn Sudun naar God in de inleiding van zijn humorboek en hij noemt Hem degene die ‘opluchting schenkt bij beklemming, die verdriet uitwist en laat verdwijnen door het scheppen van blijdschap.’ God zelf heeft de humor geschapen om de mensen hun verdriet te laten vergeten, en wie zou dan nog kritiek uit kunnen oefenen op de grapjes van de auteur? (Vrolijk 1998, p. 2 Arabic text).

Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Nafzawi, de vijftiende-eeuwse auteur van een soort Arabische Kama Soetra, doet het niet anders. Zijn boek, ‘de Zoetgeurende Tuin,’ is een buitengewoon nuchter commentaar op de verhouding tussen mannen en vrouwen. Zo verklaart hij onomwonden dat het mannelijk orgaan minstens zes vingerbreedtes lang moet zijn om voor vrouwen enig nut te hebben. Er staan tips in hoe men een abortus kan opwekken, hoe men erectieproblemen behandelt en wat men kan doen tegen okselgeur. In de inleiding op zijn werk noemt ook hij God als degene die de wereld zo gemaakt heeft dat mannen en vrouwen genot ontlenen aan elkaars geslachtsorganen en dat zij geen rust kennen voordat die twee bij elkaar gekomen zijn (Al-Nafzawi 1999, p. 3). Al-Nafzawi laat het echter niet bij het inroepen van Gods autoriteit. In zijn inleiding noemt hij uitdrukkelijk de grootvizier van de heerser van Tunis, die hem aanspoorde het boek te schrijven en ook nog enkele suggesties deed voor het verhogen van de kwaliteit ervan (Ibid., p. 4).

Wie zou zijn stem kunnen verheffen tegen het onverslaanbare koppel van God en sultan?

Staatscensuur

Tot zover de strategieën die schrijvers zelf konden hanteren om niet in de problemen te geraken. Maar wat als dit allemaal niet mocht baten en de auteur tegelijkertijd niet verstandig genoeg was om met de noorderzon te vertrekken? Wat deed het overheidsapparaat zelf om controle uit te oefenen over ongewenste boeken als de genoemde zelfregulerende mechanismen niet werkten?

Soms vonden er op initiatief van de autoriteiten boekverbrandingen plaats, zoals in het geval van Ibn Hazm. Hoe vaak dit gebeurde weten we niet. Beroemde gevallen werden geboekstaafd, maar misschien waren er veel andere auteurs die hetzelfde overkwam, maar van wie we nu niets meer weten. In ieder geval kwam het vaak genoeg voor om het voor de islamitische schriftgeleerden de moeite waard te maken om er een opinie over te formuleren. De strenge Hanbalitische rechtsschool, een der vier orthodoxe juridische richtingen, ging hierin het verst. Volgens de veertiende-eeuwse Hanbalitische jurist Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya kon het vernietigen van een boek nooit een onrechtmatige daad opleveren en waren dezelfde regels van toepassing als bij de vernietiging van onwettige goederen als wijn en hasjiesj. Andere rechtsscholen gingen niet zo ver (Rosenthal 1995, p. 39-40).

Waren er echter ook andere, minder extreme middelen beschikbaar voor de overheid om censuur uit te oefenen? In de klassieke islam bestond er niet zoiets als een aparte, officiële organisatie die deze taak had, maar wel was er het instituut van de ‘hisba,’ in principe een soort economische controledienst annex zedenpolitie annex dienst openbare werken onder leiding van een ‘muhtasib,’ een woord dat vaak vertaald wordt met marktmeester. De hoofdtaak was de controle van de soeks, de maten en gewichten et cetera. In de praktijk had de marktmeester het recht om naar eigen inzicht corrigerend op te treden voor zo ver het niet om de in de koran zelf genoemde vergrijpen ging. Hij kon daarbij naar eigen inzicht handelen en hoefde niet te wachten op een officiële klacht. In het al eerder genoemde boek over bestuurskunde van al-Mawardi staat een passage volgens welke de marktmeester het recht heeft om bedrog of de verspreiding van verkeerde ideeën tegen te gaan: wie knoeit in het vak van de jurisprudentie zonder de juiste kwalificaties dient terechtgewezen te worden. Als religieuze commentatoren opinies verspreiden die in tegenspraak zijn met de orthodoxie, dan dient de marktmeester daar een eind aan te maken (Al-Mawardi 1996, p. 269-270).

De vraag is nu of de marktmeester niet alleen de personen vervolgde die ongewenste opinies verspreidden, maar ook degenen aanpakte die boeken verspreidden waarin die opinies opgeschreven stonden? Met andere woorden: werden de boekhandelaren aansprakelijk gesteld voor de inhoud van hun handelswaar? De boekhandel was een florerende bedrijfstak, waarin de handel in papier en schrijfmaterialen samenging met het leveren van kant-en-klare handschriften van veelgevraagde teksten of het bemiddelen in diensten van professionele kopiisten. Hiertoe dienden de boekhandels vaak als een soort uitleenbibliotheek: ze leenden de handschriften in hun handelsvoorraad uit om ze op bestelling af te laten schrijven. Zoals dat in de Midden-Oosterse bazareconomie annex gildensysteem gebruikelijk is klonterden de boekhandelaren bij elkaar in aparte wijken of delen van de soek. Over de boekhandel is het een en ander geschreven (zie bijvoorbeeld Pedersen 1984), maar er wordt geen gewag gemaakt van een eventuele controle over de boekhandel om ongewenste boeken te weren, van razzia’s of inbeslagnames. Dat wil niet zeggen dat er geen controle was: naar analogie met de ‘would-be’ juristen en korancommentatoren mag je aannemen dat ook boekhandelaren vervolgd konden worden of dat in ieder geval hun handelswaar het voorwerp van controle was. Toch is de situatie verre van duidelijk. Van het genootschap van de ‘Zuivere Broeders’ is al vermeld dat zijzelf liever in de anonimiteit bleven, maar dat ze wel hun religieus-filosofische traktaten onder de boekhandels verspreidden. Kennelijk waren ze wel bang voor repercussies ten aanzien van henzelf, maar hoefden ze niet te vrezen voor invallen bij de boekhandel en confiscatie van hun teksten.

Wederom geeft het geruchtmakende proces tegen de Perzische mysticus al-Hallaj wat nuttige informatie. Bij zijn proces riep hij volgens de overlevering uit: ‘Jullie hebben het recht niet om mij op basis van een technisch detail buiten de wet te stellen. Boeken van mij, die de orthodoxie hooghouden, liggen op dit moment in de boekhandels.’ Het feit dat zijn boeken, waarvan de inhoud als orthodox gold, vrij verkrijgbaar waren suggereert dus dat boeken die dat niet waren wel degelijk uit de boekwinkels geweerd werden, misschien door zelfcensuur van de handelaren, maar misschien ook onder druk van de autoriteiten. Na het proces en de executie van al-Hallaj besloten de autoriteiten om zijn boeken tot niet-orthodox te verklaren, en er wordt expliciet vermeld dat ‘alle boekhandelaren opgeroepen werden om onder ede te verklaren dat ze nooit meer een werk van al-Hallaj zouden kopen of verkopen’ (Kritzeck 1964, p. 109, 113).

Conclusie

In de religieus geïnspireerde klassieke islamitische wereld werd de vrijheid van meningsuiting door de islamitische wet beperkt, met de doodstraf als ultieme sanctie. In het gebied dat niet door de islamitische wet bestreken werd konden de autoriteiten naar eigen inzicht optreden. Er bestond censuur, maar dan voornamelijk in de vorm van zelfcensuur binnen de groep der geletterden. Auteurs bedienden zich van allerlei strategieën om minder aanvaardbare teksten toch geaccepteerd te krijgen of om problemen met het gezag te voorkomen. Het is aannemelijk dat de autoriteiten controle uitoefenden over de florerende bedrijfstak van de boekhandel via de ‘hisba,’ eigenlijk een controledienst voor de markten. De autoriteiten konden actief verhinderden dat teksten verspreid werden, bijvoorbeeld door een directe aanwijzing aan de boekhandelaren of door de verbranding van boeken.

Bibliografie

Miguel Asín Palacios, Abenházam de Córdoba y su Historia crítica de las ideas religiosas, 5 dl., Madrid, Real Academia de la Historia, 1927-32.

S.G. Bonebakker, Nihil obstat in story-telling?, Amsterdam, Noord-Hollandsche Uitg. Mij., 1992 (Koninklijke Akademie van Weten-schappen, Mededelingen van de afdeling Letterkunde, Nwe. Reeks 55 no. 8).

Geert Jan van Gelder, The bad and the ugly, Leiden, Brill, 1988.

Der Grosse Herder, 4e ed., 13 dl., Freiburg i.Br., Herder, 1931-1935.

Ibn Battoeta, De reis, vert. door Richard van Leeuwen, Amsterdam, Bulaaq, [1997].

Joel Kraemer, Humanism in the renaissance of Islam, Leiden, Brill, 1986.

James Kritzeck, Anthology of Islamic literature, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1964.

Al-Mawardi, The ordinances of government, transl. by Wafaa H. Wahba, Reading, Garnet, 1996.

Muhammad b. Muhammmad al-Nafzawi, The perfumed garden of sensual delight, transl. by Jim Colville, London, Kegan Paul International, 1999.

Joh. Pedersen, The Arabic book, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1984.

David Piché, La condamnation parisienne de 1277, Paris, Vrin, 1999.

Franz Rosenthal, The Muslim concept of freedom, Leiden, Brill, 1960.

Idem, ‘Of making many books there is no end,’ in George N. Atiyeh, The book in the Islamic world, Albany NY, State University of New York Press, 1995, p. 33-55.

Dominique Sourdel, ‘Peut-on parler de liberté dans la société de l’Islam médiéval?,’ in George Makdisi [et al.], La notion de liberté au Moyen Age: Islam, Byzance, Occident, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1985, p. 119-133.

Salomon Swigger, De Arabische Alkoran, door de Zarazijnsche en de Turcksche prophete Mahometh, Hamburg, gedruckt voor Barent Adriaensz. Berentsma, 1641.

Arnoud Vrolijk, Bringing a laugh to a scowling face: a study and critical edition of the ‘Nuzhat al-nufus wa-mudhik al-`abus’ by `Ali Ibn Sudun al-Basbugawi (Cairo 810/1407 – Damascus 868/1464, Leiden, Research School CNWS, 1998 (Contributions by the Nederlands-Vlaams Instituut in Cairo; CNWS Publications, Vol. 70).

Catherine Wilson, ‘Modern Western philosophy,’ in Seyyed Hossein Nasr [et al.], History of Islamic philosophy, London, Routledge, 1996, Part II, p. 1013-1029.