Noam Chomsky

We live in extraordinarily dangerous times. Climate breakdown is upon us, yet nation-states and their leaders continue to pursue policies based on “national security” and the pursuit of geopolitical objectives. The transition to a clean and sustainable global energy landscape is hampered both by powerful interests linked to the fossil fuel economy and lack of international cooperation. In fact, the war in Ukraine, which runs on fossil fuels, is not only delaying climate action but has increased reliance on the very energy sources that drive global warming and poison the planet. Indeed, the war has been a godsend to the fossil fuel industry. “Drill, baby, drill” is back with a vengeance, and oil and gas companies are reaping unprecedented profits as families everywhere are struggling with skyrocketing energy costs.

To be sure, “savage capitalism,” as Noam Chomsky powerfully remarks in this exclusive joint interview with economist Robert Pollin, is unleashed today even more destructively than it has in the past. Yet, as Pollin so astutely points out, there are ways to tame global warming and make a successful transition to a sustainable future based on clean energy systems (which do not include nuclear power plants or so-called negative emission technologies). In fact, Chomsky and Pollin agree that, in large part, it is political will that stands in the way of securing the future of humanity and the planet. As Chomsky notes, the task of political education in the age of global warming is analogous to the task of philosophy as described by Ludwig Wittgenstein: “to show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.”

Robert Pollin

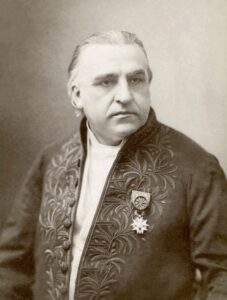

Noam Chomsky is institute professor emeritus in the department of linguistics and philosophy at MIT and laureate professor of linguistics and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Program in Environmental and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. One of the world’s most cited scholars in modern history and a critical public intellectual regarded by millions of people as a national and international treasure, Chomsky has published more than 150 books in linguistics, political and social thought, political economy, media studies, U.S. foreign policy and world affairs, and climate change.

Robert Pollin is distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. One of the world’s leading progressive economists, Pollin has published scores of books and academic articles on jobs and macroeconomics, labor markets, wages, and poverty, environmental and energy economics. He was selected by Foreign Policy Magazine as one of the “100 Leading Global Thinkers for 2013.” Chomsky and Pollin are co-authors of Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (2020).

C. J. Polychroniou: Noam, the systemic impacts of the war in Ukraine are enormous and they include economic shocks, food and energy security, geopolitical dimensions, and climate change. With regard to the latter, while it is difficult to make an accurate estimate of the climate impact of the war in Ukraine, it is crystal clear that it hinders current efforts to curb global warming and may even alter long-term strategy on climate action and action plan. How exactly are the war in Ukraine and the climate crisis connected, and why are governments doubling down on coal, oil and gas instead of doubling down on the clean energy transition?

Noam Chomsky: An independent observer looking at the world today might well conclude that it is being run by the fossil fuel and military industries, or by lunatics. Or both.

The scientific literature is harrowing, regularly showing that earlier dire warnings were too conservative and that we are careening towards disaster at a frightening pace. Even without reading the literature, anyone with eyes open can see that nature is saying “enough”: extreme heat, huge floods, devastating drought and severe water crises, large regions of the earth approaching the point where they will soon be uninhabitable.

How are we reacting? The basic character is captured by a clip from the marvelous satirical journal Onion — except that it is perhaps even beyond their imagination. It is real. And reported, with disbelief, in the mainstream:

‘In a paradox worthy of Kafka, ConocoPhillips plans to install “chillers” into the permafrost — which is thawing fast because of climate change — to keep it solid enough to drill for oil, the burning of which will continue to worsen ice melt.’

In his bitter antiwar essays, Mark Twain wielded his formidable weapon of satire against the perpetrators. But when he reached the renowned General Funston, he threw up his hands in despair: “No satire of Funston could reach perfection,” Twain lamented, “because Funston occupies that summit himself…. [He is] satire incarnated.”

What is happening before our eyes is unleashed savage capitalism as satire incarnated. Even Twain would be silenced.

To see what is at stake, consider some basic facts. “Arctic permafrost stores nearly 1,700 billion metric tons of frozen and thawing carbon. Anthropogenic warming threatens to release an unknown quantity of this carbon to the atmosphere.… Carbon dioxide emissions are proportionally larger than other greenhouse gas emissions in the Arctic, but expansion of anoxic conditions within thawed permafrost and soils stands to increase the proportion of future methane emissions. Increasingly frequent wildfires in the Arctic will also lead to a notable but unpredictable carbon flux.”

The carbon flux may be unpredictable in detail, but the resulting devastation is all too predictable in its general outline. How then does unleashed savage capitalism respond? Simple. Let’s employ our best brains to find ways to slow the melting down a little so that we can pour more poisons into the atmosphere for profit, and as a side effect, release those Arctic permafrost stores into the atmosphere more rapidly so as to make life unlivable.

Unfortunately, the observation generalizes. We find satire incarnate wherever we turn, even in marginal corners. Thus, one argument against solar energy is land use. A real problem, especially in the U.K., where golf courses take up over four times as much space as solar power, so we learn from political economist Adam Tooze’s invaluable Chartbook.

Satire incarnate is just the cutting edge. It brings out dramatically the elements of dominant economic institutions that are lethal if unleashed. It would be hard to conjure up a more fitting epitaph for the species — or more accurately, for the institutions that have become dominant as what we call civilization marches forward.

The Ukraine war finds its natural place in this collective madness. One outcome of Putin’s criminal aggression and the consequent sanctions regime is to restrict the fossil fuel flow from Russia on which Europe relies, particularly the German-based system that is its economic powerhouse. Economic consequences for Europe are severe, though not for the U.S., which is largely immune; or for that matter for Russia, which at least for now is profiting handsomely from rising oil prices and has many eager customers outside of Europe.

Europe is seeking alternative sources of oil and gas, a bonanza for the U.S. fossil fuel industry, rewarded with new markets and expansive drilling opportunities to enable it to destroy life on Earth more effectively. And the military industry could hardly be more ecstatic as the killing and destruction mount.

People seem to have a different view. In Germany for example, where 77 percent of the population “believe that the West should initiate negotiations to end the Ukraine war.”

One can think of other reasons to bring the horrors to a quick end, but the fate of organized human society is surely one. The Ukraine war has reversed the limited efforts to address the mounting crisis of environmental destruction. While it should have accelerated efforts to move rapidly towards sustainable energy, that was not the path chosen by the political leadership. Rather, the choice has been to accelerate the race to the abyss.

What should be done at this critical moment is outlined perceptively by economist and political analyst Thomas Palley: “The European Union must build trade and commerce with Russia. That is an economic marriage made in heaven. Russia has resources and needs technology and capital goods. Europe has technology and capital goods and needs resources.”

And more generally, “What should be done is a profound recalibration that diminishes the influence of the US in Europe, strengthens the European Union, and aims for inclusion of Russia in the European family as envisaged by President Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990,” in his call for a “common European home” from Lisbon to Vladivostok with no military alliances, no victors or defeated, and a common effort to move towards a more just social democratic future — if not beyond.

“Getting there is beginning to look impossible,” Palley adds. But accommodation among the great powers must be achieved, and soon, if there is to be any hope for decent survival. The madness of devoting scarce resources to slaughter and destruction when cooperation to meet major crises is an absolute necessity simply cannot be tolerated.

Unleashed savage capitalism is a death sentence for the species. That has long been obvious, even before it reached the level of satire incarnated. The crucial word is “unleashed.” The leash should be, and can be, in the hands of those who have higher aims in life than enriching private power and enhancing the political forces that prefer global dominance to the Gorbachev vision.

We should not underestimate the barriers in economic and political realms, and also in the doctrinal systems that articulate and protect the structures of power. The matter is of particular importance in the U.S., for reasons too obvious to elaborate.

The barriers within the reigning doctrinal system are illustrated in a very revealing current essay in the major establishment journal. The authors are two well-informed foreign policy analysts at the more liberal end of received opinion, Fiona Hill and Angela Stent.

Their article illustrates graphically the extraordinary subordination to official doctrine that confines U.S. elites to an “alternative reality” that has little resemblance to the world. Confined within their self-reinforcing cocoon, they are simply incapable of comprehending the global reaction to their vocation of endless criminality.

Hill-Stent harshly condemn the Global South — most of the world — for its failure to join the U.S. in its profound distress “that Russia has violated the UN Charter and international law by unleashing an unprovoked attack on a neighbor’s territory.” The Global South even sinks so low as to “argue that what Russia is doing in Ukraine is no different from what the United States did in Iraq or Vietnam.”

Hill-Stent attribute this failure to rise to our level of nobility and understanding of global reality to Putin’s machinations. What else could account for such blindness?

Could there be a different reason, for example, the fact that outside the cocoon people actually look at the world and quickly discover that the U.S. is far and away the world leader in violating the charter and international law by unleashing unprovoked attacks — worldwide, even thousands of miles away? And could it be that they see that U.S. aggression in Iraq and Vietnam is an incomparably graver crime even than Putin’s aggression in Ukraine?

And as a minor footnote, perhaps these “backward” peoples are well aware that the Russian aggression, which they in fact harshly condemn, was in fact extensively provoked — as Western commentators tacitly acknowledge in their own curious way by conjuring up for this case alone the novel phrase “unprovoked attack,” which has become de rigeur in polite circles for the plainly provoked Russian aggression.

Given the climate of irrationality and subordination to doctrine that reigns in the U.S. it is necessary to reiterate, once again, that extensive provocation does not provide any justification for criminal aggression.

The Hill-Stent exercise in obfuscation is, regrettably, an instructive example of prevailing mentality among the more liberal sectors of doctrinal orthodoxy, amplified by conformist media and journals of opinion. These sectors of course play a prominent role in shaping the climate in which policy is designed and implemented, a matter of overwhelming significance in the most powerful state in world history, with no close competitor.

The realities of the modern world impose unique responsibility on Americans. Ludwig Wittgenstein described the task of philosophy as “to show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle,” the flies being philosophers who buzz about in conventional confusions. Analogously, one task for those concerned about the future is to try to help educated elites find their way out of the doctrinal cocoon in which they have confined themselves, and to liberate the general public from the “alternative reality” that elite circles have constructed.

No small task, but an essential one.

Military operations produce enormous amounts of greenhouse gas emissions as capacity for and use of military force depend on energy that comes in the form of fossil fuels. In fact, the U.S. military emits more carbon into the atmosphere than some countries do and has a long history of fighting wars for oil. Is it realistic therefore to expect serious climate action on the part of the world’s major powers if they continue to ignore how militarism fuels the climate crisis?

Chomsky: And, we may add, if they continue to ignore how the climate crisis fuels militarism. The climate crisis engenders conflicts. We’ve already witnessed that in Syria and Darfur, where migrations caused by unprecedented droughts provided a large part of the background for the horrors that ensued. There are looming crises that may put even these awful events in the shade.

India and Pakistan are at sword’s point, engaged in constant armed confrontations. Both are suffering severely from global warming. One-third of Pakistan is under water, sometimes many feet deep, following an intense heatwave and a long monsoon that has dumped a record amount of rain. In neighboring India, poor peasants in mud huts are trying to survive drought and heat reaching 50 degrees Celsius (50ºC), virtually unlivable, of course without air conditioning. Meanwhile the governing authorities race to produce more and better means of destruction. Another grim case of satire incarnates, perhaps. The sources of their water supplies are shared and diminishing. The rest can be left to the imagination.

What isn’t left to the imagination is that both are armed to the teeth, including huge nuclear arsenals, an unsustainable arms race for much smaller Pakistan. For both, it is an unconscionable waste of resources that are desperately needed to face their shared and devastating problems of global warming and other forms of destruction of the environment.

India-Pakistan is only one of many such examples of impending disaster. The U.S., though unusually privileged, is not immune, as we have seen in the past months.

As usual, the crises are not just human destruction of the environment. Scandals proliferate. The city that has been worst hit is Jackson, Mississippi, the state capital. The water system has been failing for years, and now its residents are literally without potable water — in a country with unparalleled wealth and natural advantages.

“Experts say this crisis was years in the making, a result of inadequate funding for essential infrastructure upgrades. For the past year, leaders of this majority-Black, Democrat-led city have pushed for additional funding from the White Republicans who run the state. Little has come of those appeals.”

Deeply rooted social pathologies make their own contributions to human misery, exacerbating those produced by destroying the environment and radical misuse of resources. The U.S. is, furthermore, far in the lead in accelerating the militarization of the world.

More tasks for Americans, and not them alone.

Bob, the world was falling short of meeting its climate goals even before the outbreak of the Ukraine war. Indeed, it’s obvious by now that climate goals cannot be reached without fast and radical action. In that context, can you talk a bit about the role that carbon tax and cap-and-trade play as strategies for reducing carbon emissions?

Robert Pollin: Let’s first be clear on what we mean by the world’s “climate goals.” The most basic goals were set out in 2018 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the leading global organization that brings together and synthesizes climate change research. In its landmark 2018 special report “Global Warming of 1.50C,” the IPCC established two primary goals: to reduce global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by about 45 percent in 2030 relative to the 2010 level and to achieve net zero emissions by around 2050. The IPCC argued that these goals must be achieved to have a reasonable chance of limiting global warming to 1.50C above pre-industrial levels. The IPCC had concluded that limiting global warming to 1.50C above pre-industrial levels is needed to dramatically lower the likely negative consequence of climate change.

Just since the IPCC’s 2018 report came out, we have been seen much more severe impacts of climate change than what the IPCC had anticipated in terms of heat extremes, heavy rains and flooding, droughts, sea level rise and biodiversity losses. To take just one recent example, average daily temperatures were sustained at over 110°F during the heat wave in India this past May. The intensifying climate crisis is making such episodes increasingly frequent. As Noam discusses, the war in Ukraine is only worsening the situation. It is therefore fair to conclude that the IPCC’s 2018 targets should be understood as what is minimally necessary to move onto a viable global climate stabilization path. This conclusion has been affirmed by the IPCC itself in its even more extensive 2022 follow-up studies.

Where does the world stand today in terms of achieving the IPCC’s emission reduction targets? As of the most recent data from the International Energy Agency (IEA) — the best-known and thoroughly mainstream organization that develops global energy models — global CO2 emissions were at around 36 billion tons in 2019. This represents a roughly 70 percent emissions increase since 1990 and a 14 percent increase just since 2010. More to the point, according to the IEA’s projections for future emissions under alternative realistic scenarios, emissions will fall barely at all by 2030 and will not come close to achieving the zero emissions target by 2050.

Specifically, in its 2021 “World Energy Outlook” report, the IEA developed two scenarios for future CO2 emissions levels based on what it considers to be realistic assessments of the current global policy environment. One is what the IEA terms a “Stated Policies Scenario.” This scenario “explores where the energy system might go without additional policy implementation.” It is based on taking “a granular, sector-by-sector look at existing policies and measures and those under development.” In short, this scenario aims to project what CO2 emissions will be through 2050 if global policies remain basically fixed along their current trajectory. In this scenario, global CO2 emissions will not fall at all by 2030 and will decline by only 6 percent, to 33.9 billion tons, by 2050. In short, assuming we take climate science seriously, this is nothing less than a doomsday scenario.

Under a second “Announced Pledges Scenario,” the IEA “takes account of all of the climate commitments made by governments around the world, including Nationally Determined Contributions as well as longer term net zero targets, and assumes that they will be met in full and on time.” Under this more aggressive scenario, the IEA projects that emissions will still fall by only 7 percent as of 2030, and that by 2050, the emissions level will be at 20.7 billion tons — i.e. well less than halfway to achieving the zero emissions goal by 2050. In other words, even this more aggressive IEA scenario also is not too far from a doomsday scenario, assuming we take climate science seriously.

The IEA does also develop a scenario through which the world can reach zero emissions by 2050. The difference between the IEA’s stated policies and announced pledges scenarios relative to their net zero emissions by 2050 scenario is what the IEA terms an “ambition gap.” The question for getting to zero emissions is therefore to figure out how to close this “ambition gap,” i.e., how to avoid, somehow, a full-scale global climate catastrophe.

How much can carbon tax or carbon cap policies contribute here? Both of these measures aim to directly reduce the consumption of oil, coal and natural gas. This is critical since CO2 emissions from burning coal, oil, and natural gas to produce energy is, by far, the largest source of overall CO2 emissions, and thus, the major cause of climate change.

In principle at least, a carbon cap establishes a firm limit on the allowable level of emissions for major polluting entities, such as utilities. Such measures will also raise the prices of oil, coal and natural gas by limiting their supply. A carbon tax, on the other hand, will directly raise fossil fuel prices to consumers, and aim to reduce fossil fuel consumption through the high prices. Either approach can be effective as long as the cap is strict enough, or tax rate high enough, to significantly reduce fossil fuel consumption and as long exemptions are minimal to none. Raising the prices for fossil fuels will also create increased incentives for both energy efficiency and clean renewable investments, as well as a source of revenue to help finance these investments.

However, significant problems are also associated with both approaches. The first is their impact on the budgets of middle- and lower-income people. All else equal, increasing the price of fossil fuels would affect middle- and lower-income households more than affluent households, since gasoline, home-heating fuels and electricity absorb a higher share of lower-income households’ consumption. There is an effective solution here, developed initially by my PERI coworker Jim Boyce. That is to rebate to lower-income households a large share, if not most, of the revenues generated either by the cap or tax to offset the increased costs of fossil-fuel energy. Boyce termed this a “cap-and-dividend” program.

Another major problem with carbon caps is with enforcement. In particular, when these cap programs are combined with a carbon permit option — as in “cap-and-trade” policies — the enforcement of a hard cap becomes difficult to sustain or even monitor. So instead of measures that could be major contributors to fighting climate change, we end up with a mess of accounting tricks and exceptions. For the most part, this has been the experience thus far with cap-and-trade policies, both in the U.S. and Europe.

There are some easy fixes for this problem, as we have discussed in previous interviews. The most straightforward is to establish hard caps, such as utilities being required to reduce their fossil fuel consumption by, say, 5 percent per year, every year, with no exceptions and no cap-and-trade escape hatches. The CEOs of corporations who fail to hit these hard caps would face serious criminal liability.

Arguments in favor of the deployment of negative emission technologies, such as direct air capture and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, are gaining ground these days in spite of their technological immaturity. Same goes for nuclear power plants and even geo-engineering in spite of the inherent risks that they entail. What role can such strategies play in the effort to make a complete break from reliance on fossil fuels?

Pollin: Neither negative emissions technologies nor nuclear power can likely contribute significantly to building an alternative global clean energy infrastructure. Indeed, it is more likely that they will create still more severe problems.

Let’s start with nuclear. It does have the important benefit that it generates electricity without producing CO2 emissions. But nuclear also creates major environmental and public safety concerns, which only intensified after the March 2011 meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant in Japan and still more, after Russia seized control of the Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plants in the early stages of its invasion of Ukraine six months ago. Nuclear disasters at both Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhia became active threats immediately. Just over the past month, the Zaporizhzhia plant has come under intense siege. Thus, as of August 3, the Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency Rafael Grossi stated that conditions at Zaporizhzhia are “completely out of control” underlying “the very real risk of a nuclear disaster.” By mid-August, the BBC described “the growing concern over safety at the site…as both sides accuse each other of shelling the area.” The BBC article quotes U.N. Secretary General António Guterres’s warning that “any potential damage to Zaporizhzhia is suicide.”

Negative emissions technologies include a range of measures whose purpose is either to remove existing CO2 or to inject cooling forces into the atmosphere to counteract the warming effects of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. One category of removal technologies is carbon capture and sequestration. A category of cooling technologies is stratospheric aerosol injections.

Carbon capture technologies aim to remove emitted carbon from the atmosphere and transport it, usually through pipelines, to subsurface geological formations, where it would be stored permanently. The general class of carbon capture technologies have not been proven at a commercial scale, despite decades of efforts to accomplish this. After all, as we have discussed in previous interviews, carbon capture would be the savior for the oil, coal and natural gas industries if the technology could be made to work commercially at scale. However, even if carbon could be successfully captured at reasonable costs, the technology would still face the threat of carbon leakages that would result under flawed transportation and storage systems. These dangers will only increase to the extent that carbon capture becomes commercialized and operates under an incentive structure in which maintaining safety standards cuts into corporate profits.

The idea of stratospheric aerosol injections builds from the results that followed from the volcanic eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991. The eruption led to a massive injection of ash and gas, which produced sulfate particles, or aerosols, which then rose into the stratosphere. The impact was to cool the Earth’s average temperature by about 0.60C for 15 months. The technologies being researched now aim to artificially replicate the impact of the Mount Pinatubo eruption through deliberately injecting sulfate particles into the stratosphere. Some researchers contend that doing so would be a cost-effective method of counteracting the warming effects of CO2 and other greenhouse gases.

However, the viability of stratospheric aerosol injections as a major climate solution has been refuted repeatedly by leading researchers in the field. For example, the Oxford University climate scientist Raymond Pierrehumbert, a major contributor to various IPCC studies, is emphatic in his 2019 paper, “There is No Plan B for Dealing with the Climate Crisis,” that this type of geo-engineering — what he refers to “albedo hacking” — does not offer a viable solution to the climate crisis. Pierrehumbert writes:

‘The excess carbon dioxide that human activities inject into the atmosphere has a warming effect that extends essentially forever, whereas the stratospheric aerosols meant to offset that warming fall out of the atmosphere in about a year. It’s just a matter of gravity –stuff denser than its surroundings falls — aided a bit by atmospheric circulations that enhance the removal. This is why the cooling effects of even a major volcanic eruption like Pinatubo dissipate after two years or so. Hence, whatever level of albedo hacking is needed to avoid a dangerous level of warming must be continued essentially forever.’

Pierrehumbert further writes that “We simply do not know the way the climate will respond to these novel forcings, or how our social and political systems will respond to these disruptive and possibly ungovernable technologies.”

Renewable energy critics argue that wind and solar are not reliable sources because of their variability. Others argue that wind farms encroach on pristine environment and destroy a country’s natural habitat, as is the case with the installation of thousands of wind turbines on scores of Greek islands in the Aegean Sea. How would you respond to such concerns, and are there ways around them?

Pollin: Three major sets of challenges arise in building a high-efficiency/renewable-energy dominant global energy infrastructure. They include the two you mentioned, i.e., 1) intermittency with solar and wind energy; and 2) the land use requirements for renewables, especially solar and wind. The third major challenge is the heavy mineral requirements as inputs for the clean energy infrastructure. In the interests of space, I will focus on just the first two.

Intermittency refers to the fact that the sun does not shine, and the wind does not blow, 24-hours a day. Moreover, on average, different geographical areas receive significantly different levels of sunshine and wind. As such, the solar and wind power that are generated in the sunnier and windier areas of the globe will need to be stored and transmitted at reasonable costs to the less sunny and windy areas. In fact, these issues around transmission and storage of wind and solar power will not become pressing for many years into the clean energy transition, probably for at least a decade. This is because fossil fuels, along with nuclear energy will continue to provide a baseload of non-intermittent energy supply as these energy sectors proceed toward their phaseout while the clean energy industry rapidly expands. Fossil fuels and nuclear energy now provide roughly 85 percent of all global energy supplies. Even with a phase out to zero by 2050 trajectory, fossil fuels will continue to provide most of the overall energy demand through about 2035. Meanwhile, fully viable solutions to the technical challenges with transmission and storage of solar and wind power — including around affordability — should not be more than a decade away, certainly as long as the market for clean energy grows at the rapid rate that is necessary. For example, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that global battery storage capacity could expand between 17 — 38-fold as of 2030.

The issue of land use requirements is frequently cited to demonstrate that building a 100 percent renewable energy global economy is unrealistic. But these claims are not supported by evidence. Thus, the Harvard University physicist Mara Prentiss shows, in her 2015 book Energy Revolution: The Physics and the Promise of Efficient Technology, as well as in her more recent follow-up discussions, that well below 1 percent of the total U.S. land area would be needed through solar and wind power to meet 100 percent of U.S. energy needs.

Most of this land use requirement could be met, for example, by placing solar panels on rooftops and parking lots, then operating wind turbines on about 7 percent of current agricultural land. Moreover, the wind turbines can be sited on existing operating farmland with only minor losses of agricultural productivity. Farmers should mostly welcome this dual use of their land, since it provides them with a major additional income source. At present, the U.S. states of Iowa, Kansas, Oklahoma and South Dakota all generate more than 30 percent of their electricity supply through wind turbines. The remaining supplemental energy needs could then be supplied by geothermal, hydro and low-emissions bioenergy, which are all non-intermittent renewable sources. This particular scenario includes no further contributions from solar farms in desert areas, solar panels mounted on highways or offshore wind projects, among other supplemental renewable energy sources. However, if handled responsibly, all of these options are also viable possibilities.

It is true that conditions for renewable energy production in the United States are more favorable than those in some other countries. Germany and the U.K., for example, have population densities seven to eight times greater than the U.S. and also receive less sunlight over the course of a year. As such, these countries, operating at high efficiency levels, would need to use about 3 percent of their total land area to generate 100 percent of their energy demand through domestically produced solar energy. But using cost-effective storage and transmission technologies, the U.K. and Germany can also import energy generated by solar and wind power in other countries, just as, in the United States, wind power generated in Iowa could be transmitted to New York City. Any such import requirements are likely to be modest.

What about Greece? With co-authors, I am currently working on a study that considers the land use issues in Greece within the framework of achieving a zero-emissions economy there by 2050. I hope to be able to give more details on our results soon. For now, suffice it to say that there is no need for Greece to be installing wind farms on pristine sites. As with the U.S., there is more than sufficient land area in Greece to meet 100 percent of the country’s energy demand through investments in high efficiency and building a renewable infrastructure situated on artificial surfaces like rooftops, parking lots, highways and commercial locations, as well as, to a relatively modest extent, agricultural lands.

Noam, we are the only species to evolve a higher intelligence, but we are not making the right decisions over climate and the environment. Is it because of politics and the way the world economy functions, or perhaps because of fears that the challenge of global warming is too overwhelming so we might as well go on with business as usual, make some alterations along the way and just hope for the best?

Chomsky: Evolution of higher intelligence is an intriguing scientific problem. It is even possible that we are the only species in the accessible universe to have evolved what we call higher intelligence, or at least to have sustained it without self-destruction. Yet.

As for why the existential crises that may soon end sustainable life on Earth receive far too little attention, one can think of many possible reasons. There is also a deeper question lingering in the not too remote background. The question burst into consciousness with dramatic intensity 77 years ago, on August 6, 1945. Or should have.

On that fateful day we learned that human intelligence had registered a grand achievement. It had devised the means to destroy everything. Not quite yet, in fact, though it was clear that further technological progress would soon reach that point. It did, in 1952, when the U.S. exploded the first thermonuclear weapon, and the Doomsday Clock advanced to two minutes to midnight. It did not become that close to terminal disaster again until Trump’s term, then moving on to seconds as analysts abandoned minutes.

The question that arose with stark clarity 77 years ago was whether human moral intelligence could rise to the level where it could control the impulse to destruction. Can the gap be overcome? The record so far is not promising.

The game is not over unless we choose to end it. The choice is unavoidable. How humans will decide is by far the most important question that has arisen in the brief sojourn of humans on Earth. We will soon provide the answer.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).