To Address Increasing Inequality And Global Poverty, We Must Cancel Debt

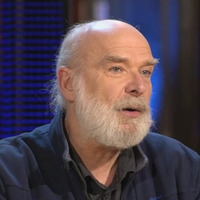

Massive debt levels are a feature of contemporary capitalism that cannot be eradicated without radical change, says political scientist Éric Toussaint.

“The indebtedness of the working classes is directly connected to the widening poverty gap and increasing inequality, and to the demolition of the welfare state that most governments have been working at since the 1980s,” says Toussaint in this exclusive interview for Truthout.

Toussaint — a historian and international spokesperson for the Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt (CADTM), and author of several books on debt, development and globalization — shares his thoughts on debt, inequality and contemporary socialist movements in the conversation that follows.

C.J. Polychroniou: Over the past few decades, inequality is rising in many countries around the world, both across the Global North and the Global South, creating what UN Chief António Guterres called in his foreword to the World Social Report 2020 “a deeply unequal global landscape.” Moreover, the top 1 percent of the population are the big winners in the globalized capitalist economy of the 21st century. Is inequality an inevitable development in the face of globalization, or the outcome of politics and policies at the level of individual countries?

Éric Toussaint: Rising inequality is not inevitable. Nevertheless, it is obvious that the explosion of inequality is consubstantial with the phase that the world capitalist system entered into in the 1970s. The evolution of inequality in the capitalist system is directly related to the balance of power between the fundamental social classes, between capital and labor. When I use the term “labor,” that means urban wage-earners as well as rural workers and small-scale farming producers.

The evolution of capitalism can be divided into broad periods according to the evolution of inequality and the social balance of power. Inequality increased between the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the first half of the 19th century and the policies implemented by the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States in the 1930s, and then decreased up to the early 1980s. In Europe, the turn towards lower inequality lagged 10 years behind the United States. It was not until the end of World War II and the final defeat of Nazism that inequality-reducing policies were put in place, whether in Western Europe or Moscow-led Eastern Europe. In the major economies of Latin America, there was a reduction in inequality from the 1930s to the 1970s, notably during the presidencies of Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico and Juan D. Perón in Argentina. In the period from the 1930s to the 1970s, there were massive social struggles. In many capitalist countries, capital had to make concessions to labor in order to stabilize the system. In some cases, the radical nature of social struggles led to revolutions, as in China in 1949 and Cuba in 1959.

The return to policies that strongly aggravated inequality began in the 1970s in Latin America and part of Asia. From 1973 onward, the dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet (advised by the “Chicago Boys,” the Chilean economists who had studied laissez-faire economics at the University of Chicago with Milton Friedman), the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, and the dictatorships in Argentina and Uruguay are just a few examples of countries where neoliberal policies were first put into practice.

These neoliberal policies, which produced a sharp increase in inequality, became widespread from 1979 in Great Britain under Margaret Thatcher, from 1980 in the United States under the Reagan administration, from 1982 in Germany under the Kohl government, and in 1982-1983 in France after François Mitterrand’s turn to the right.

Inequality increased sharply with the capitalist restoration in the countries of the former Soviet bloc in Central and Eastern Europe. In China from the second half of the 1980s onward, the policies dictated by Deng Xiaoping also led to a gradual restoration of capitalism and a rise in inequality.

It is also quite clear that for the ideologues of the capitalist system and for many international organizations, a rise in inequality is a necessary condition for economic growth.

It should be noted that the World Bank does not consider a rising level of inequality as negative. Indeed, it adopts the theory developed in the 1950s by the economist Simon Kuznets, according to which a country whose economy takes off and progresses must necessarily go through a phase of increasing inequality. According to this dogma, inequality will start to fall as soon as the country has reached a higher threshold of development. It is a version of pie in the sky used by the ruling classes to placate the oppressed on whom they impose a life of suffering.

The need for rising inequalities is well rooted into World Bank philosophy. Eugene Black, World Bank president in April 1961, said: “Income inequalities are the natural result of the economic growth which is the people’s escape route from an existence of poverty.” However, empirical studies by the World Bank in the 1970s at the time when Hollis Chenery was chief economist contradict the Kuznets theory.

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty presents a very interesting analysis of the Kuznets curve. Piketty mentions that at first, Kuznets himself doubted the real interest of the curve. That did not stop him from developing an economic theory that keeps bouncing back and, like all economists who serve orthodoxy well, receiving the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (1971). Since then, inequalities have reached levels never before seen in the history of humanity. This is the result of the dynamism of global capitalism and the support it receives from international institutions that are charged with “development” and governments that favor the interests of the 1 percent over those of the enormous mass of the population, as much in the developed countries as in the rest of the world.

In 2021, the World Bank reviewed the Arab Spring of 2011 by claiming, against all evidence, that the level of inequality was low in the entire Arab region, and this worried them greatly as it was symptomatic of faults in the region’s supposed economic success. As faithful followers of Kuznets’ theory, Vladimir Hlasny and Paolo Verme argue in a paper published by the World Bank that “low inequality is not an indicator of a healthy economy.”

Gilbert Achcar summarizes the position taken by Paolo Verme of the World Bank as follows: “in the view of the 2014 World Bank study, it is inequality aversion, not inequality per se, that should be deplored, since inequality must inevitably rise with development from a Kuznetsian perspective.”

Finally, the coronavirus pandemic has further increased the inequality in the distribution of income and wealth. Inequality in the face of disease and death has also increased dramatically.

Neoliberal policies have created massive debt levels for so-called emerging markets and developing countries, with debt threatening to create a global development emergency. What’s the most realistic solution to the debt crisis in developing countries?

The solution is obvious. Debt payments must be suspended without any penalty payments being paid for the delay. Beyond suspension of payment, each country must carry out debt audits with the active participation of citizens, in order to determine the illegitimate, odious, illegal and/or unsustainable parts, which must be canceled. After a crisis of the size of the present one, the slates must be wiped clean, as has happened many times before throughout human history. David Graeber reminded us of this in his important book, Debt: The First 5,000 Years.

From the point of view of the CADTM, a global network mainly active in the Global South but also in the North, the need to suspend payments and cancel debt does not only concern developing countries, whether they are emerging or not. It also concerns peripheral countries in the North like Greece and semi-colonies like Puerto Rico.

It is time to dare to speak out about canceling the abusive debts demanded of the working classes. Private banks and other private bodies have put great energy into developing policy of lending to ordinary people who turn to borrowing because their incomes are insufficient to pay for higher education or health care. In the U.S., student debt has reached over $1.7 trillion, with $165 billion worth of student loans in default, while a large part of mortgages are subjected to abusive conditions (as the subprime crisis clearly showed from 2007). The terms of certain consumer debts are also abusive, as are most debts linked to micro-credit in the South.

Indebtedness of the working classes is directly connected to the widening poverty gap and increasing inequality, and to the demolition of the welfare state that most governments have been working at since the 1980s. This is true all over the world: whether in Chile, Colombia, the Arabic-speaking region, Japan, Europe or the United States. As neoliberal policies dismantle their systems of protection, people are obliged, in turn, to incur debt as individuals to compensate for the fact that the states no longer fulfil the obligation incumbent upon them to protect, promote and enact human rights. Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya and Nancy Fraser emphasized this in their book, Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto.

What are the alternatives for a sustainable model of development?

As stated in the manifesto, “End the system of private patents!”:

The health crisis is far from being resolved. The capitalist system and neoliberal policies have been at the helm at all stages. At the root of this virus is the unbridled transformation of the relationship between the human species and nature. The ecological and health crises are intimately intertwined.

Governments and big capital will not be deterred from their offensive against the populations unless a vast and determined movement forces them to make concessions.

Among new attacks that must be resisted are the acceleration of automation/robotization of work; the generalization of working from home, where employees are isolated, have even less control of their time and must themselves assume many more of the costs related to their work tools than if they worked physically in their offices; a development of distance learning that deepens cultural and social inequality; the reinforcement of control over private life and over private data; the reinforcement of repression, etc.

The question of public debt remains a central element of social and political struggles. Public debt continues to explode in volume because governments are borrowing massively in order to avoid taxing the rich to pay for the measures taken to resist the COVID-19 pandemic, and it will not be long before they resume their austerity offensive. Illegitimate private debt will become an ever-greater daily burden for working people. Consequently, the struggle for the abolition of illegitimate debt must gain renewed vigor.

The struggles that [arose] on several continents during June 2020, notably massive anti-racist struggles around the Black Lives Matter movement, show that youth and the working classes do not accept the status quo. In 2021, huge popular mobilizations in Colombia and more recently in Brazil have provided new evidence of massive resistance among Latin American peoples.

We must contribute as much as possible to the rise of a new and powerful social and political movement capable of mustering the social struggles and elaborating a program that breaks away from capitalism and promotes anti-capitalist, anti-racist, ecological, feminist and socialist visions. It is fundamental to work toward a socialization of banks with expropriation of major shareholders; a moratorium of public debt repayment while an audit with citizens’ participation is carried out to repudiate its illegitimate part; the imposition of a high rate of taxation on the highest assets and incomes; the cancelation of unjust personal debts (student debt, abusive mortgage loans); the closure of stock markets, which are places of speculation; a radical reduction of working hours (without loss of pay) in order to create a large number of socially useful jobs; a radical increase in public expenditure, particularly in health care and education; the socialization of pharmaceutical companies and of the energy sector; the re-localization of as much manufacturing as possible and the development of short supply chains, as well as many other essential demands.

A few years ago, you argued that the socialist project has been betrayed and needs to be reinvented in the 21st century. What should socialism look like in today’s world, and how can it be achieved?

In the present day, the socialist project must be feminist, ecologist, anti-capitalist, anti-racist, internationalist and self-governing. In 2021, we commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune when people set up a form of democratic self-government. It was a combination of self-organization and forms of power delegation that could be questioned at any moment, since all mandates could be revoked at the behest of the people. It has to be clearly stated that the emancipation of the oppressed will be brought about by the oppressed themselves, or will not happen at all. Socialism will only be attained if the peoples of the world consciously set themselves the goal of constructing it, and if they give themselves the means to prevent authoritarian or dictatorial degradation and the bureaucratization of the new society.

What Rosa Luxemburg said in 1918 is as valid today as it was then: “without a free and untrammeled press, without the unlimited right of association and assemblage, the rule of the broad masses of the people is entirely unthinkable.”

She added:

Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party — however numerous they may be — is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently. Not because of any fanatical concept of “justice” but because all that is instructive, wholesome and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effectiveness vanishes when “freedom” becomes a special privilege.

Faced with the multidimensional crisis of capitalism hurtling towards the abyss due to the environmental crisis, modifying capitalism is no longer a proper option. It would merely be a lesser evil which would not bring the radical solutions that the situation requires.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Source: https://truthout.org/to-address-increasing-inequality-and-global-poverty-we-must-cancel-debt/

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, climate change, the political economy of the United States, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books, and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Arabic, Croatian, Dutch, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthout and collected by Haymarket Books; Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors); and The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthout and collected by Haymarket Books (scheduled for publication in June 2021).