ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Adapted Arguments: Logic And Rhetoric In The Age Of Genes And Hardwired Brains

It is said that the Greek philosopher Diogenes once sought to prove that the apparently unique capacity of humans to engage in logical reasoning was not really special to humans alone. His proof relied on an observation about hunting dogs. On the hunt, such dogs may have occasion to come to a fork in the road. When they do, they stop and sniff one of the two paths in the road. If they do not pick up the scent on that path, they immediately turn and run down the other path, without stopping to sniff it. Diogenes asserted that these beasts were “reasoning” as follows:

It is said that the Greek philosopher Diogenes once sought to prove that the apparently unique capacity of humans to engage in logical reasoning was not really special to humans alone. His proof relied on an observation about hunting dogs. On the hunt, such dogs may have occasion to come to a fork in the road. When they do, they stop and sniff one of the two paths in the road. If they do not pick up the scent on that path, they immediately turn and run down the other path, without stopping to sniff it. Diogenes asserted that these beasts were “reasoning” as follows:

P or Q

not P

therefore Q

Dogs may indeed have a rudimentary capacity to engage in what we call logical reasoning – even if they could not recognize the above case as an example of modus tollendo ponens. But that, pace Diogenes, is really the point. No animal other than humans can engage in abstract logical reasoning. No animal other than humans can think in terms of Ps and Qs, or conditionals, or negations, or inference rules. Until recently, it was assumed that when humans engaged in logical reasoning, we were engaging that specific part of the brain that enables us to solve abstract logic problems like the ones found in textbooks on formal logic. To be sure, emotions or passions surrounding a particular situation might “cloud” our logical reasoning processes and make it difficult for us to come to a logical conclusion about a particular matter. But neither the emotions surrounding a situation, nor any other concrete aspect of the situation, could change the actual reasoning process that we used. In short, it was assumed that humans come equipped with one all-purpose reasoning mechanism in our brain, and that we utilize only that particular mechanism when we reason about anything.

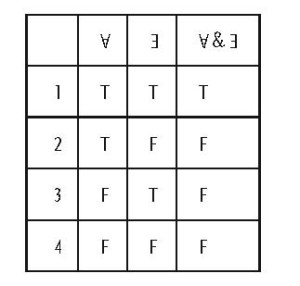

But that may be wrong. Recent research by evolutionary psychologists seems to indicate that humans “reason” dramatically differently – and better – when we are “processing” a social exchange situation that is open to the possibility of cheating (see Cosmides and Tooby 1992a). The point is not that the rules of formal logic do not apply to such situations. The point is that humans do not automatically apply the rules of formal logic to such situations. Indeed, we automatically apply other rules – probably located in another part of our brains – to those situations alone. This is fortunate however, because the human capacity to reason in general is (as I said) relatively poor when compared to our capacity to “reason” about social exchange situations in which we ourselves or others can be cheated.

The explanation that evolutionary psychologists give for this is simple. When the human mind evolved, several hundred-thousand years ago, humans did not need to be able to reason about Ps and Qs. Nor did we really need to be able to reason in the abstract. But we did need to be able to figure out when we were being cheated in a social exchange situation. Thus we evolved a narrowly tailored capacity to enable us to do just this. Such a capacity is, in effect, a cheater-detector. It seems that humans have an extraordinarily well-developed cheater-detector mechanism.

The implications of this research for scholars of logic and rhetoric are enormous. If humans really do “process” logical arguments differently based solely on the content of those arguments, then this might help us to understand better why some arguments seem “naturally” more persuasive – or at least more salient – than others. I deal extensively with this research and its implications for communication in chapter ten of my book The Return of Human Nature, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. (Gander 2002). What follows is a condensed version of that analysis. I begin with a brief discussion of evolutionary psychology. Next, I discuss precisely how our cheater-detector might work. Finally, I conclude with some thoughts about what this means for scholars of logic and rhetoric.

1. Evolutionary Psychology and the Return of Human Nature

If you have even a passing familiarity with the recent torrent of articles and best-selling books written by scientists and targeted toward an audience of educated non-scientists, you cannot help noticing it: Human nature is back. At least by those who remain up-to-date on such matters, the thinking now seems to be that a complex and richly detailed human nature really does exist, that it is to a very large degree scientifically knowable, that it differs markedly between the sexes, that it delimits a set of viable human cultures, and that, because of all this, it makes a big difference when we set out to discuss moral, ethical, and political questions.

The return of human nature has been facilitated, in no small part, by the emergence of a branch of science that has come to be known as evolutionary psychology. Succinctly put, evolutionary psychology can be defined as an interdisciplinary science that attempts to understand how the human mind works by viewing the mind as – in the words of Steven Pinker, a leading evolutionary psychologist – “a system of organs of computation, designed by natural selection to solve the kinds of problems our ancestors faced in their foraging way of life, in particular, understanding and outmaneuvering objects, animals, plants, and other people” (21). The systems of organs of computation to which Pinker refers are sometimes called mental modules by evolutionary psychologists. Apparently we have mental modules that enable us to perform an enormously wide variety of tasks, including: keeping track of degrees and types of relatedness among our kin; selecting a mate; deciding what amount of resources to invest in our various children; understanding how the minds of other individuals work; recognizing faces; rotating images in our minds; detecting when someone is trying to cheat us; and executing numerous other mental operations (see ibid.).

To the extent that culture is created by collections of evolved individual minds working in some degree of unison, evolutionary psychologists claim special insight not only into how cultures are generated, but also into which cultures are humanly possible. The phrase evolutionary psychology itself came into widespread use as the result of an enormously influential volume of essays entitled The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture edited by Jerome H. Barkow, Leda Cosmides, and John Tooby. As the editors of that volume explain:

Evolutionary psychology is simply psychology that is informed by the additional knowledge that evolutionary biology has to offer, in the expectation that understanding the process that designed the human mind will advance the discovery of its architecture. It unites modern evolutionary biology with the cognitive revolution in a way that has the potential to draw together all of the disparate branches of psychology into a single organized system of knowledge. (1992b: 3)

The critical point here is that evolutionary psychology understands the human mind not as an essentially blank slate upon which culture writes its various dictates, nor as a mysterious vessel that now contains the essence of our humanity (an essence that may once have been thought to reside in the soul). Rather, evolutionary psychology understands the mind as simply another part of the human body, albeit an especially complex part. Still, like all parts of body the mind has a specific function. Its function, according to evolutionary psychologists, is information-processing or computation. The mind runs “algorithms” that have been programmed into it by nature. Also, according to evolutionary psychologists, like the human body the human mind must have evolved over the course of the last two-million or so years of humanoid evolution.

This understanding of the mind is simultaneously appealing and distressing. It is appealing because it seems to argue for the overall psychic unity of mankind and womankind. It seems to suggest that underneath the outwardly different and sometimes bizarre cultures that anthropologists tell us exist and have existed on the planet earth, men and women are now, and have been for at least the past one-hundred thousand years, pretty much the same everywhere. Each sex shares basically the same pattern of emotional reactions, the same reasoning processes, the same desires for the same types of physical and social rewards, the same attitudes toward others and toward the physical world, and so forth. The hundred thousand year figure, by the way, comes from the fact that given the glacially slow pace of humanoid evolution, the human mind itself has not changed appreciably from what it was structurally one-hundred thousand years ago.

But this understanding of the human mind is also distressing because it seems strongly to suggest that the human mind as it exists today may be tragically ill-equipped to deal with the problems faced by modern humans. After all, our hunter-gatherer ancestors of one million, or even one-hundred thousand, years ago never faced the problems attendant to noisy, overcrowded urban population centers. Additionally, they never needed to compute probabilities concerning situations that occurred much beyond the realm of their small foraging group, nor could they even have known that such situations occurred. And they certainly never needed to negotiate the complex demands of a modern workplace in which men and women cooperate and compete side by side very often within a cultural and legal framework governed by the strictures of political correctness, the explicit requirements that equality be maintained between the sexes, and the ever-present threat of sexual harassment lawsuits.

So life was different for our hunter-gatherer ancestors. No big news there. But in some respects life was also very much the same. Humans are amazingly social. Indeed, that is surely one of the defining characteristics of our species. A large part of that sociability involves exchange with other humans. Of course, you don’t have to be a free-trade fanatic to see that individuals have an obvious incentive to engage in mutually beneficial trades. Such trades can actually produce more resources for all, resulting in a type of non-zero sum environment that is the very definition of progress.

On the other hand, you don’t have to be a cynic like Diogenes to see that, while mutually beneficial trades may be best for society as a whole, for any given trade, each individual involved has the incentive to benefit himself at the expense of his trading partner. If I agree to give you some meat from a hunt in exchange for some water you have drawn from a lake some distance away, and if I get the water from you without giving the meat in exchange – perhaps because you lack the mental capacity to see that you are paying a cost (water) without receiving a benefit (meat) – then I may survive while you perish. Eventually, the mental mechanism that helped me to survive – a mechanism that assessed costs and benefits, and enabled me to see when I might be coming out behind on any given exchange – would come to predominate in the species. That, at any rate, is the story of how we might have come to possess a specific cheater-detector mechanism. But do humans have such a mechanism, and if so, how does it work?

2. Cheater-Detectors and Logical Minds

To begin this discussion, I invite the reader to answer the two questions that appear below. (These questions were adapted from the work of Leda Cosmides and John Tooby 1992a.)

Suppose you are in charge of hospitality at the ISSA conference. You know that various conference members will be attending various receptions. You have developed a system of keeping track of the various conference members and the receptions they will be attending. Your system is complex, but it includes the following rule:

Rule 1: If a conference member is attending the reception at the Park Plaza, then he or she must be in Group 3.

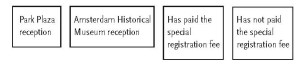

Your assistant has been working hard all day to sort conference members and the receptions they will be attending based solely on the above rule. But you suspect your assistant is suffering from jet-lag and may therefore have become confused. Below are four cards (Figure 1). Each card corresponds to one conference member. One side of the card indicates a reception that the member will be attending, the other side indicates the one group the member is in. Here is your first question: Which one(s), if any, of these cards must you turn over to be absolutely certain that rule 1 has been followed?

After answering that question, consider another very similar situation. Suppose you are in charge of hospitality at the ISSA conference. You know that various conference members will be attending various receptions. You also know that, because it has an open bar, many conference members want to attend the reception at the Park Plaza. Unfortunately, that location is relatively small. Hence you establish the following rule:

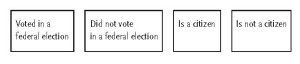

Rule 2: If a conference member is attending the reception at the Park Plaza, then he or she must have paid a special registration fee.

Your assistant has been working hard all day to sort conference members and the receptions they will be attending based solely on the above rule. But you suspect your assistant is suffering from jet-lag and may therefore have become confused. Below are four cards (Figure 2). Each card corresponds to one conference member. One side of the card indicates a reception that the member will be attending, the other side indicates whether the member has paid the special registration fee. Here is your second question: Which one(s), if any, of these cards must you turn over to be absolutely certain that rule 2 has been followed?

After answering these questions, you may notice that they both have exactly the same logical form – If P then Q – where P corresponds to a conference member is attending the reception at the Park Plaza and Q corresponds either to he or she must be in Group 3 or he or she must have paid a special registration fee. The negation of an If-then statement of this form is: P and not Q. Hence, for both questions above, the correct answer is that you would need to turn over only the first card and the last card, because only on those cards could you possibly encounter a case of P and not Q on the same card.

You might think that individuals would get the correct answer to each of these questions as often as they got the incorrect answers since both questions have exactly the same form. Only their content is different. But strikingly this does not seem to be the case. In fact, individuals do dramatically better in correctly answering the second question, by a ratio of about 3 to 1 (see Cosmides and Tooby 1992a: 187). Just because both of these questions take the same form, the observed discrepancy must therefore have something to do with the content of each question. Look again at the second question. In that question P can be understood as a “benefit.” We know that going to the Park Plaza reception is something that many people want to do, presumably because they see it as in some way beneficial. Similarly, in the second question Q can be understood as a cost. One needs to pay a special fee to be able to go to the Park Plaza reception. Now, a person who takes a benefit without paying the requisite cost (P and not Q) is a cheater.

This little example – and the very significant experimental research on which it is based – seems to show that humans have a specific mental ability to detect cheating in social exchange situations, and that this ability operates independently of our ability to carry out logical reasoning. This mechanism is (as the above example shows) better at detecting cheaters than our “logical reasoning” “module” is at detecting violators of simple descriptive rules like: if a conference member is attending the reception at the Park Plaza, then he or she must be in Group 3. Perhaps even more interestingly, when the rules of formal logic differ from the “rules” or “algorithms” used by our cheater detectors we are better able to detect cheaters by using the cheater detector than we would be by using the rules of formal logic. The evolutionary psychologists Cosmides and Tooby argue, correctly I think, that the following two rules are logically different, but equivalent from the perspective of a social exchange (ibid. 188).

Rule 3: If you give me your watch, I’ll give you $20.

Rule 4: If I give you $20, you give me your watch.

Notice that the formulation of Rule 3 is identical to the formulation of the above Rules 1 and 2. Thus in Rule 3 P – always the first clause in the conditional statement – corresponds to the phrase if you give me your watch while Q – always the second clause in the conditional statement – corresponds to the phrase I’ll give you $20. Notice also that in Rule 3 P is the benefit (to me) and Q is the cost (to me) in the exchange.

But for Rule 4 P corresponds to the phrase I give you $20 while Q corresponds to the phrase you give me your watch. Thus for Rule 4 P is the cost (to me) and Q is the benefit (to me) in the social exchange. But, as Cosmides and Tooby write, “No matter how the contract is expressed, I will have cheated you if I accept your watch but do not offer you the $20, that is, if I accept a benefit from you without paying the required cost.”

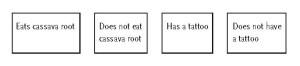

Now suppose you show two groups of individuals the following sets of cards (Figure 3).

Suppose further that you gave one group Rule 3 and asked that group which cards would need to be turned over to detect violators of that rule, while you gave a second group Rule 4 and asked that group which cards would need to be turned over to detect violators of that rule. If we approach social exchange situations that implicate the possibility of cheating logically, we would expect that the first group would do substantially better at the assigned task than the second group. This is because the first group was working from a rule that was logically equivalent to the conditional If P then Q, and could thus be negated by P and not Q. But if those in the second group used the negation P and not Q as applied to their “switched” formulation of the rule, they would turn over the third card P and the second card not Q – exactly the wrong two cards. Remarkably, both groups do equally well at detecting cheaters and, again, much better than they do at detecting violations of simple descriptive rules (ibid. 188-9). It seems, then, that when we “reason” about social exchange situations that might involve cheating we turn “off” our logical reasoning module and turn “on” our cheater detection module. This result also seems to show that humans are able to reason equally well from the perspective of either individual in a social exchange situation.

Further, there is evidence suggesting that the content specific nature of the cheater detector module is extremely fine tuned. It appears that the module gets turned on only when we reason about a social exchange situation that involves the possibility of cheating, but also, that the module gets turned on in these situations even if we do not understand the cultural context of the social exchange. For example, most Americans would doubtless understand the following statement

Rule 5: If you vote in a federal election then you must be a U.S. citizen as a type of social exchange situation open to the possibility of cheating. An individual may try to vote without being a citizen. Thus if you were to show Americans the following four cards (Figure 4)

you probably would not be surprised if they were good at detecting violators of this rule. You might suspect that their success came not from the use of any cheater detection module, nor even from the use of any reasoning process, but rather from the fact that Americans are simply familiar with this aspect of their culture. But this appears not to be the case. When subjects were given a simple descriptive rule with which they could be expected to be familiar – such as, If one goes to Boston, one takes the subway – they were no where near as good at detecting violations of this culturally familiar rule as they were at detecting violators of a culturally familiar rule that implicated the possibility of cheating in a social exchange situation (see ibid.).

But what clinches this point is an examination of how well people do detecting violators of rules when they have absolutely no familiarity with the cultural context in which the rule is embedded. Two groups of people were given the following rule:

Rule 6: If a man eats cassava root then he must have a tattoo on his face

They were then shown the following cards (Figure 5):

Notice, first, that this rule does not correspond to any cultural practice with which any subject would likely be familiar, because it was simply made up by the researchers. Notice also that this rule need not necessarily implicate a social exchange situation involving the possibility of cheating. In fact, one group was told that in the particular culture from which this statement was drawn, having a tattoo on one’s face meant that one was married, and all married men just happened to live on the side of the island on which only cassava root grows. This explanation makes the above rule a simple descriptive rule, similar to the rule that if one eats sauerkraut then he must be German. The other group, however, was told that cassava root is a delicacy that not everyone is allowed to eat. It was explained that one requirement of eating this was having a tattoo. Remarkably, the second group did dramatically better, by a margin of three to one, in detecting violators of the rule than the first group, even though the rule and the cards were exactly the same for both groups (see ibid. 186; 196-7; but see also Miller: 302-3). The almost inescapable conclusion is that the second group had their cheater detectors activated. Also, in general, individuals do better at detecting violators of culturally unfamiliar rules that implicate the possibility of cheating in a social exchange situation than they do at detecting violations of culturally familiar rules that are merely descriptive but do not implicate the possibility of cheating (Cosmides and Tooby 1992a: 184-187).

Finally, consider this. If you were designing a mental module to be used by ancestral humans for whom social exchange was a vital part of life, and if efficiency were a critical concern – remember any module eats metabolic energy and takes up brain space – what would be the minimum requirements for this module? Obviously, you would want it to be good at detecting cheaters. But would you necessary want it to be good at detecting altruists? Probably not, since altruists pose no threat to society. And, indeed, it appears that while we do have a mental module for detecting cheaters, neither that module, nor any other module we may have, works very well at detecting altruists. Subjects were given many of the same rules and cards I have been discussing above, and asked which cards they would need to turn over to determine who had “violated” the rule by being altruistic – that is, by paying a cost but not taking a benefit. Subjects did no better at this task then they did at determining violations of simple descriptive rules (see ibid. 193-95).

3. Some Implications for Logic and Rhetoric

The evidence presented above, and more, seems to suggest strongly that we do have a specific mental module for cheater-detection, and that this module is not a by-product of our general ability to reason. It is a hardwired, “dedicated” module designed to focus specifically on one set of “inputs” (the possibility of cheating in a social exchange situation) and return one set of “outputs” (the benefit-cost structures that are necessary to evaluate whether one has been cheated). Perhaps the most significant implication of this research is that the process of human reasoning – a process that is still thought to be so insensitive to content that the premises of arguments can be represented in the formal logic as merely letters like “P” or “Q” – is itself different depending upon the content of those Ps and Qs. If this is true, we may need to rethink, for example, the way in which we administer intelligence tests – specifically tests which purport to measure an individual’s skill at inferential reasoning. From now on, we may need to specify which inferential reasoning skills – for example, ones about social exchange or ones about descriptions of the world – that we are attempting to measure, and we may need to formulate the content of the questions accordingly. Cosmides and Tooby also note that if their findings hold up, we may be justified in looking for different reasoning processes in other areas of life including: the evaluation of threats; the benefits associated with joining certain “coalitions” of other humans; and of course mate choice (see ibid. 166). Finally, the existence of a cheater detector fits perfectly with a kind of urethics that foregrounds fundamental fairness, as opposed (say) to one that foregrounds blind altruism. The point is that humans naturally compare costs and benefits, and look for cheaters in any social exchange situation. Thus from a rhetorical perspective, arguments that suggest that individuals may be taken advantage of by cheaters in their midst could seem especially persuasive.

Consider, in this regard, the fairly recent history of the whole welfare reform debate in America. During the 1980s – the so-called decade of greed – president Reagan went a long way in laying the groundwork for dismantling the federal welfare bureaucracy, and curtailing the overall amount of welfare payments to individuals, by explicitly arguing that large numbers of individuals were abusing the welfare system. “Welfare queens,” as they came to be known, were supposedly everywhere, driving Cadillacs and wearing expensive clothes. Interestingly, Reagan himself did not coin that term “welfare queen.” The term was invented by Chicago newspaper writers to refer to one Linda Taylor who, in 1976, was charged with defrauding the federal government by, among other things, using several aliases to collect more welfare than that to which she was legally entitled (see Zucchino, 65).

In the 1990s Bill Clinton then went on to complete the welfare revolution by restructuring the system along lines that were not all that different from those laid down by Reagan. Significantly, Clinton did this in part by relying on a very similar, though perhaps a gentler, version of Reagan’s arguments. Recall Clinton’s pledge in his 1992 acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention to “end welfare as we know it,” and his promise to say to those on welfare: “You will have, and you deserve, the opportunity through training and education, through child care and medical coverage, to liberate yourself. But then, when you can, you must work, because welfare should be a second chance, not a way of life.” From a rhetorical perspective that is also informed by evolutionary psychology, the public policy debate surrounding welfare unfolded in ways that seem quite consistent with what we have theorized about the natural tendency of humans to foreground the potential for cheating in a social exchange situation.

Notice, for example, that both Clinton and Reagan saw that what disturbed most Americans was not the existence of welfare as such, but rather, the potential for cheating the system, and, more importantly, the inability of individual Americans directly to detect such cheating. Huge welfare bureaucracies may be good at taking advantage of economies of scale when delivering their “product,” but they wildly set off our initiate cheater-detectors. Yet, because of their very size, welfare bureaucracies prevent individual taxpayers from effectively monitoring the system. This helps to explain an aspect of the welfare debate that bedeviled Ted Kennedy liberals, and also that probably caused them to think badly of their fellow citizens. Throughout the 1980s, and especially in the early 1990s, liberals were saying, quite correctly, that the whole welfare debate was grossly out of proportion to the amount of money that welfare payments themselves represented as a percentage of the overall federal budget. Liberals wondered how average Americans could be so exercised over so trivial a percentage of the federal budget, especially when other areas of the budget – defense spending, for example – went seemingly unscrutinized. Liberals concluded that Americans must be greedy and selfish. But this conclusion was simply wrong, for it failed to take account of precisely how our cheater-detection mechanism works. Welfare is a particularly salient example of social exchange. Thus, as I have said, it immediately sets off our cheater-detectors. Hence, it may not be that the average American is greedy and selfish. It may rather be that the average American has a natural impulse not to “define deviance down,” especially with respect to social exchange situations. This impulse was reflected everywhere in the welfare debates of the 1990s, including especially in the title of the very bill that was being debated. Although it is sometimes called the “welfare reform” act for short, we should not forget that on August 22, 1996 President Clinton signed what is formally known as the “Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.”

Notice also that the welfare debate has seemed to come full circle, back to explicit questions concerning who deserves welfare and by whom (federal or state governments) the benefits are to be distributed. In their 1971 book The “Deserving Poor,” Joel Handler and Ellen Hollingsworth note that as far back as the English Poor Laws of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, governments have sought to determine who is poor through no fault of his or her own (as might be the case if poverty results from blindness or other physical handicap, or from widowhood) and who is poor because he (the male pronoun is appropriate here) is just lazy. Handler and Hollingsworth also note that from its inception in 1935 to roughly the mid 1960s, Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), a federal program for “deserving” poor, relied heavily for its rhetorical appeal on the perception that benefits went to mothers who were widows. That appeal may have lost a good deal of its utility in the early and mid sixties as welfare rolls, which had remained fairly steady for the previous thirty years, shot up dramatically. There is a huge literature devoted solely to answering the vexing question of exactly why we saw such a dramatic raise in welfare recipients beginning in the early sixties (see, for example, Murray). At least one explanation ties the raise in both welfare recipients and in overall welfare payments to a rise in illegitimate births which began during this period. This is usually regarded as a “conservative” explanation for the problem. But even as early as 1962 liberals may have sensed the danger that this explanation posed to a continuation of a federally funded welfare system. It cannot be a coincidence that in 1962 the Kennedy administration successfully fought to rename ADC by inserting the critical word “Families,” thus rechristening the major federal welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). Liberals know about the rhetorical power of naming, just as do conservatives. If renaming AFDC happened to give the impression to most taxpaying Americans that welfare payments were going to what those taxpaying Americans probably defined as families – i.e., to households with a father, a mother, and children – this would surely not be the first time that a noble lie was used in the service of what many thought to be a worthy purpose. The point I want to emphasize, however, is that the rhetorical appeals used by all sides in the various economic policy debates of the last one hundred years or so seemed consistent with a social ethics that is deeply concerned about the possibility of cheaters in our midst.

I hope to have shown that there is some evidence that the argumentation patterns humans use today bear some resemblance to the types of arguments that may have been “adaptive” in our hunter-gatherer past, and that these argumentative patterns may, in some colloquial sense, be “hardwired” into our brains. At the very least, there is fruitful potential for collaboration in this area between evolutionary psychologists and scholars of logic and argumentation.

REFERENCES

Barkow, J. H., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (Eds.) 1992. The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Clinton, W. J. 1992. Acceptance address at the Democratic National Convention. New York Times, July 17, 1992, A. 14.

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. 1992a. Cognitive adaptations for social exchange. In Barkow, Cosmides & Tooby, 1992.

Cosmides, L., et. al. 1992b. Introduction: Evolutionary psychology and conceptual integration. In Barkow, Cosmides & Tooby, 1992.

Gander, E. 2002. The Return of Human Nature: How Evolutionary Psychology is Changing the Way Talk About Ourselves. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Miller, G. 2000. The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature. New York: Anchor Books.

Murray, C. 1984. Losing Ground: American Social Policy 1950-1980. New York: Basic Books.

Pinker, S. 1997. How the Mind Works. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Zucchino, D. 1997. The Myth of the Welfare Queen. New York: Simon & Schuster.