ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Towards A Proposition Of The Argumentative Square

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

In his semantic description of language, Ducrot puts forward a rather provocative thesis, with respect to traditional semantic theory, namely, that words do not mean anything if meaning is understood in terms of vocabulary, by which he defies the primacy of the informative in the account of meaning. The informative is said to be derived from and subordinated to the argumentative, which is, in turn, presented as inscribed in language and defined in terms of argumentative orientation, topoi and enunciators (viewpoints). The notion of lexical enunciator unfolds the argumentative potential in a word (lexeme), i.e., points of view formulated according to four basic topical forms. It is tempting to imagine the four topical forms as a taxonomy of viewpoints and present them in a square model.

The square model has already been used in logic and narrative semiology, and there were attempts to see Ducrot’s work related to and even explicable by them, especially, since the names of some relations (e.g. contradiction and contrariety) repeat in some or all of the theoretical frameworks. Ducrot has explicitly drawn a line of separation between, on the one hand, the semiotic square and the logical square, and, on the other hand, his own theoretical path[i]. On a closer inspection – which is impossible to be deployed here due to the limitations of time and space – one could indeed realize there is no direct theoretical import between them. The logical and semiotic squares differ from the one that could be reconstructed from Ducrot’s work to a great extent in their fundamental elements, function and nature, definitions of relations and treatment of meaning and truth.

As the four-angled form itself has nothing to do with the incompatibilities between Aristotle, Greimas and Ducrot, it is possible to attempt and arrange the four topical forms in a square model. However, the structural relations in – what let it for the purpose of this paper be called the argumentative square – must, accordingly, be defined and understood differently than in the logical or semiotic squares.

2. Ducrot – Theory of argumentation in the language-system – TAL

The general thesis of TAL is that “the argumentative function of a discourse segment is at least partly determined by its linguistic structure, and irrespective of the information which that segment conveys about the outer world” (Ducrot 1996: 104). Let me summarize Ducrot’s explanation of the main concepts introduced by the general thesis of TAL on a single example. Suppose two people are considering how to get back to their hotel:

1.

A: “Would you like us to walk?”

B: “It’s far away.”

An argumentative function is actually an argumentative orientation of an enunciator’s viewpoint, which means that a certain viewpoint is “represented as being able to justify a certain conclusion, or make that conclusion acceptable.” (Ducrot 1996: 104) In the example provided, the answer would by most of us be understood as oriented towards a refusal of the suggestion. Representing a certain distance by terms ‘far away’ functions as an argument for not walking. A special stress is put on the expression represented as being able to justify instead of simply saying it justifies a certain conclusion. It means that it is not a question of what cause or factor leads effectively to a certain conclusion, but rather what argument is represented as having such a strength within a particular discourse.

It is important, though, that our answer does not convey information about the (f)actual distance. The term ‘far’ can be used fairly irrespective of the actual quantity of metres/kilometres, and is, therefore, not a description of reality. I am fairly sure there is no consensus over how much is ‘near’ and from which point on a distance is considered to be ‘far’. Instead, the term rather conveys our attitude towards a distance and our company. Namely, if, for example, B would favour a walk with A, he/she would probably find the same distance less bothering and, in a certain sense, even too short, and might accordingly answer:

1.

(A: “Would you like us to walk?”)

B: “Of course, it’s nearby,”

which would, in turn, be oriented towards accepting the proposal. We can see that an argumentative function is dependent on the choice of words we used, which led Ducrot to conclude that an argumentative function is at least partly determined by the linguistic structure. Basically this thesis is understood in terms of enunciators, whose argumentatively oriented viewpoints are said to be intrinsic to the very language system. By different enunciators[ii], found within a single utterance, Ducrot understands the sources of different points of view, or better, viewpoints with different argumentative orientation. Ducrot uses the term borrowed from Aristotle and refers to the viewpoints of nunciators as topoi. Topos is the element of an argumentative string that bridges the gap from an argument to a conclusion by relating the properties of the former and the latter. It is a shared belief, common knowledge accepted beforehand by a certain community and rarely doubted about. We can analyse the following argumentative string:

2.

“It is far, so let’s take a cab”

into an argument A: “It is far”

a conclusion C: “let’s take a cab”

and topos T: If the distance is great, one should take a means of transport.

Within this paper I would like to concentrate on the concept of lexical enunciator. Lexical enunciator stands for the idea that argumentatively oriented viewpoints are a constitutive part of lexicon items – words. The explanation of lexical enunciators requires a few more theoretical concepts. Topos has three characteristics: it is general, common and scalar. Scalarity of a topos is understood as the scalarity of the relationship between the property of an argument and the property of a conclusion. The properties themselves are scalar – they are properties you can have more or less of. The degree of one property implies the degree of the other. The four possible combinations of degrees of involved properties are called topical forms. Referring to our last example (2), the following topical form was used:

FT: The greater the distance, the more one should rely on a means of transport.

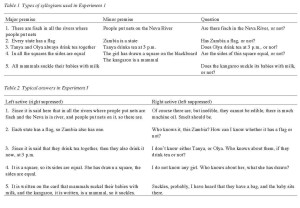

Let me now demonstrate in detail how it is possible to analytically reconstruct topical forms as constitutive parts of lexemes. Ducrot considers the following four adjectives that seem to have common informative content: ‘courageous’, ‘timorous’, ‘prudent’, and ‘rash’. In principle they all relate to confronting danger, to the fact of taking risks, but differ to a great extent in argumentative sense (see Scheme 1). Regarding the two properties P (taking risks) and Q (quality) that support the argument and the conclusion, we can distinguish two contrary topoi: T1, which relates the notion of risk to the notion of goodness, and T2, which relates the notion of risk to the notion of badness. Each contrary topos can, according to the notion of scalarity, be understood in terms of a scale with two converse topical forms (FT1’ – FT1’’ and FT2’ – FT2’’) standing for the converse argumentative orientations. Thus we get the following scheme:

Scheme 1

The four topical forms can be formed as follows:

T1: taking risks (P) is a good thing (Q)

FT1’: the more one takes risks, the worthier one is (+P,+Q)

FT1’’: the less one takes risks, the less worthy one is (-P,-Q)

T2: taking risks (P) is a bad thing (Q)

FT2’: the more one takes risks, the less worthy one is (+P, -Q)

FT2’’: the less one takes risks, the worthier one is (-P,+Q)

The converse topical forms are the two directions of the same topical scale composed of many degrees. A point of conversion presents a problem, namely, a person either performs or does not perform an act. That is why the line in the model presenting the converse relation is disconnected.

We can now see how the scheme explains the points argued by Ducrot.

The meaning of lexical enunciators can be analytically translated into topical forms that have different argumentative orientation. Lexical enunciators are units of the lexicon and topical forms are understood as constitutive of their intrinsic meaning (which is primarily argumentative). This is one of the arguments, according to Ducrot, for his thesis that argumentative orientation is inscribed into the very language-system.

Although it seems to be analytically possible to distinguish the objective objective (informative) content from the subjective (argumentative) orientation, Ducrot tries to prove that they are actually amalgamated, and that the common objective component observed in the two contrary topoi is merely illusory. The smallest denoted component is already seen from opposing points of view that build up into two different notions – in Ducrot’s example one perspective deals with risks that are worth taking (P1), while the other, in fact, considers the risks as unreasonable to be taken (P2). By this Ducrot proves that tempting as it might be to consider that the argumentative is merely added on top of the informative, the two are actually amalgamated to the extent that what is perceived as the informative is derived from and dependent on the argumentative (P1 and P2 instead of P). In the case of lexical enunciators the viewpoint contained in a lexical unit contains the idea of quality[iii], namely, conclusion seems to be a judgement, an attribution of value to what is observed. It seems, therefore, that by communicating we, contrary to our belief, do not so much convey the information of what happened, but at the same time place a much greater stress on our attitude towards the occurrence and persons involved.

In accordance with his already mentioned belief that viewpoints are represented as being able to justify a certain conclusion, Ducrot claims that we choose (not necessarily consciously or strategically) the appropriate lexical item (that is, item with appropriate argumentative orientation) with respect to the attitude we adopt towards the person spoken to[iv] or our discursive intentions[v] to create our version of what is happening.

3. A proposition of the argumentative square

A proposition of the argumentative square is derived from Ducrot’s oppositions between topical forms. As the analysis of lexical enunciators showed, an important factor in the definition of relations is also the quality attributed to an entity, which reflects our attitude towards an entity and/or our communicative intentions. The terms that will be used in the explanation of the following scheme are taken from articles reporting on a particular football match. It is my belief that the distribution of terms into their relational slots of the square model is highly dependent on an actual discourse, therefore, let me first give an outline of the context within which articles were written and published. On 2nd April, 1997, national football teams of Slovenia and Croatia met in the qualifications for the World Cup in France, 1998. Before the match the Croatian team was, by both sides, considered to be the favourite. Still, they were under pressure, because they badly needed to win and score three points to get qualified. The score was a draw – 3:3, which is important to remember and compare to interpretations it underwent in reports. A draw meant that each of the teams got one point. For the Slovenian team this was the first point ever scored in the qualifications for the world championship. A draw for them was a success, although this point was not enough for them to participate in the World Cup. For the Croatian team, on the other hand, there was still a chance to get qualified, but their next opponent was expected to be much tougher and this chance seemed rather meagre. The terms used in the example were collected from several articles published in the Slovenian as well as Croatian newspapers.

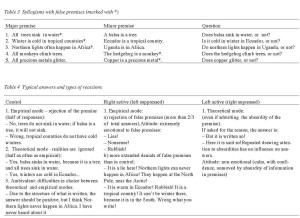

The argumentative square comparing definitions of the result could be formed in the following way (the reconstructed topical forms are included in the explanations of the respective relations):

Scheme 2

Contrariety is primarily the relation between topoi, that is, between two contrary perspectives and evaluations of seemingly the same occurrence (P). However, the occurrence is far from being the same. The first topos presupposes the match to be a true reflection of skills (P1), and the second, on the contrary, presupposes the match not to be indicative of the real quality of the teams (P2). The reporters seem to be reporting on two distinct matches – P1 and P2 – and, accordingly, applying two contrary topoi:

T1: Success (in P1) is to be attributed a positive value.

T2: Success (in P2) is to be attributed a negative value.

Although reporters are all referring to the same match, the readership is actually offered two contrary accounts that, at the level of social signification, construct two different pictures and form opposing attitudes. That is why definitions can be very important, especially, when they serve as a basis for decision-making and entail social or political (re)actions[vi].

Conversity is the relation between the two opposing topical forms of the same topos. They both agree in seeing the occurrence in the same way, for example, they both deny that the match was a true reflection of skills (P2) and consequently apply topos T2. According to whether the result in such a match was considered a success or a failure, they differ in evaluation of the teams:

FT2’: The more you succeed (in P2), the less appreciation you get.

FT2’’: The less you succeed (in P2), the more appreciation you get.

Calling their performance a ‘stroke of luck’ (FT2’) attributes the team, which is represented as being successful, a negative value. I believe you would agree that a ‘stroke of luck’ implies that their success is to be attributed to good fortune or even an inexplicable coincidence, and not to their skills and capabilities. Conversely, calling their performance ‘bad luck’ (FT2’’) attributes the team, which is represented as being unsuccessful, a positive value. Again, I believe you would agree that ‘bad luck’ implies that something beyond their qualities prevented their otherwise good skills from realizing their potential.

The two crossing relations (FT1’ – FT2’ and FT1’’ – FT2’’) deserve most of our attention. It seems they would well conform to the name of joking relations. The name is taken from Mauss (Mauss 1928) and Radcliffe-Brown’s (Radcliffe-Brown 1940, 1949) texts, where they, from the anthropological point of view, examine the ways in which people within a society (they mainly focused on families) take effort to avoid conflict and thereby maintain social order. Social structure and especially structural changes, conjunction and disjunction, as in the case of marriage that draws closer two social groups that were up to then clearly distinguished, set the members of those groups into positions where there is an increased possibility of interest clash. Chances of conflict between the newly related members can be avoided in two ways: by exaggerated politeness (between son in law and mother in law) or joking (between brothers and sisters in law). Joking is understood as an avoidance of conflict and not the cause of it – the proof for that is found in Radcliffe-Brown’s substitute term permitted disrespect. It refers to the conventionalized uses of disrespect, or better, disrespect found between those members of a family, where it does not endanger communication, but is moreover a sign of social intimacy, directness and relaxed attitude. Within a social group or society, it can be quite rigidly set which of the two forms is appropriate between which members. But their precise distribution is not universal to all societies. What seems to be universal, though, is the presence of both ways of avoiding conflict and the balance of their distribution.

By introducing joking relations Radcliffe-Brown and Mauss established an important link between social structure and social interaction, which is a combination that is today becoming increasingly important in the research of the interactional basis of social life. Joking relations therefore prove to be a very important principle also for the research into contemporary societies, where family might not be recognized as the most important social group any more. The following quotations should testify to the topicality of this view today. Gumperz in his foreword to Brown and Levinson’s book (Politeness 1978) describes politeness to be “basic to the production of social order, and a precondition of human co-operation, so that any theory which provides an understanding of this phenomenon at the same time goes to the foundations of human social life.” (Foreword: XIII) Later on in the book the authors wrote: “We believe that patterns of message construction, or ‘ways of putting things’, or simply language usage, are part of the very stuff that social relationships are made of (or, as some would prefer, crucial parts of the expressions of social relations). Discovering the principles of language usage may be largely coincident with discovering the principles out of which social relationships, in their unteractional aspect, are constructed: dimensions by which individuals manage to relate to others in particular ways, ” (Brown, Levinson 1978: 55)

Reconsiderations of Mauss and Radcliff-Brown’s theories today necessarily include many concepts from contemporary anthropology, sociology and interactional studies that were not used by them. I would herewith again refer to Brown and Levinson’s study of politeness, where they enumerate the following context dependent social factors that contribute to the overall weight of a potentially offensive act and through its estimation influence the choice of higher-ordered politeness strategy: social distance[vii], power[viii] and ranking of imposition[ix]. Within this paper provisional and most simplified correlation will be adopted only to indicate a basic model against which variations in use can be observed and studied – respectful patterns of behaviour are typically (but not only!) found in situations of social distance, power difference and high rank of imposition, while joking might be most commonly (and with least risk of causing conflict) applied in relations of social intimacy, equality in power and low rank of imposition.

Joking relation could, in accordance with Ducrot’s four topical forms, be defined as the relation between those two topical forms of the contrary topoi that take up different attitudes towards the subject involved. One point of view ascribes the subject a positive value, while the other presents him in a negative manner. What connects them is, extralinguistically, the performance (or lack of performance) of seemingly the same action. However, as explained,the representation of the action involved is, intralinguistically, not the same.

For example, joking relation is the relation between ‘victory’ (FT1’) and ‘a stroke of luck’ (FT2’) that can in our case be reconstructed as follows:

FT1’: The more you succeed (in P1), the more appreciation you get.

FT2’: The more you succeed (in P2), the less appreciation you get.

By ‘victory’ one approves of the result, even if one does not like it, since it presupposes the match to be a true reflection of skills, while by a ‘stroke of luck’ one reveals that one considers the result inadmissible, since the term presupposes the match not to be indicative of the real quality of the teams, and actually implies that the result should be different if the skills were the decisive factor. Either ways, though, one team is represented as being more successful than the other, although the result was, technically speaking, a draw! The argumentative potential might be so much more obvious in the following examples. The reporter supporting the home team, which was represented as more successful, actually talked of ‘a historical victory’, ‘sensational draw’ and ‘lethal stroke’, while the reporter supporting the less successful team confirmed his definition of the result – ‘a stroke of luck’ – by calling the more successful team ‘second-class players’.

One point of view pays respect to the subject of the action, and even upgrades its qualities, which is typical of a politeness strategy, the other can be considered joking, or rude, since it downplays the exhibited value of the subject and the action it performed. The choice of either of them is dependent on the relation between the two interactants in our case reporter towards the team (or even worse, the state the team represents) and/or reporter’s intentions. With Radcliff-Brown and Mauss joking should be understood as permitted disrespect. But since communication break-down is a constitutive part of interaction, the concept of rudeness and offence should nevertheless not be neglected. The argumentative square should include both interactional functions for the purpose of explaining why and where communication went wrong.

The orientation followed throughout this explanation of the argumentative square can be summarized as follows: what we say is as important as its wording – the actual choice of words, and the word-choice is influenced by the identification of the relation between the speakers. We can, therefore, conclude that what we communicate is to a high degree dependent on who we are communicating with. This is similar to Ducrot’s statement, in which he claims that we choose lexical units with regard to our attitude towards the person spoken to and our discursive intentions – that argumentative orientation determines the informative.

Let us take another example. A student comes out of an examination room and is asked by his fellow students how demanding the lecturer was. The student might call the lecturer ‘detailed’ or ‘hairsplitting’, depending on whether he/she wants to attribute him/her positive or negative value, and whether he/she considers the lecturer’s comments appropriate or inappropriate. The argumentative square and the respective topical forms could be formed like this:

Scheme 3

T1: Accuracy is respected.

FT1’: The more one is accurate, the more one is respected.

FT1’’:.The less one is accurate, the less one is respected.

T2: Accuracy is not respected.

FT2’’: The less one is accurate, the more one is respected.

FT2’: The more one is accurate, the less one is respected.

‘Detailed’ attributes the lecturer a positive value, since it presupposes that such strictness is reasonable and as such respected. Calling a lecturer ‘hairsplitting’, on the other hand, presents him/her in a negative manner, since it presupposes that the strictness involved is unnecessary or even ill-intentional. Since we all were students once, we probably all remember that such definitions of lecturers are highly subjective, depending on our own likeness of a lecturer and/or especially the grade we received.

By calling a person ‘hairsplitting’, we might run a risk of a conflict. The most impressing thing is that we can, and I think we actually do mostly (although not necessarily strategically or consciously), change our opinion of the action and person (fake or even lie) for the purpose of keeping our relation towards the person concerned. It seems that we somehow tend to perceive the actions of some people as worth of appreciation and tend to express a higher view of their action sometimes solely for the purpose of maintaining our relation. Let us suppose a third party was present at the exam, a young assistant. After the student has left the room, the lecturer might inquire about his/her own methods, asking his/her assistant whether he/she was not too demanding. The assistant’s answer:

3. “You were quite detailed, true, but that’s what an examination is all about,”

might be understood in terms of presenting the senior as reasonable in order to maintain hierarchical relation, especially, if to his/her friends the same assistant would talk of his mentor as ‘hairsplitting’. Yet, maintaining a relation might not always be one’s intention.

We must now briefly focus on the nature of the correlation between interactional and social patterns. Although social relations and, accordingly, expected interactional patterns seem fairly rigidly imposed upon us, this is only one aspect of the relation between social order and people living it, where interactional patterns can be understood as reproducing the established social relations. This is the so called conservative or passive aspect. The other is dynamic. Here the adoption of a certain interactional pattern contributes to the creation or establishment of a certain relation between interactants – it functions as a proposal of a certain relation that can be accepted or rejected. Even towards our closest friends we can take on both kinds of attitude – respectful and joking.

Let us imagine a person A tells a person B some confidential information. Person B reveals this information to his/her partner – person C. When A finds out, he/she just might accuse B of ‘babbling out’ the secret. This definition presupposes that secrets need to be kept secret, and since B revealed it to another person, he is attributed a negative value, namely, is considered to be unreliable. C, on the other hand, wants to protect his partner saying B was ‘frank’. This is a characteristic that is respected and what it implies is that such a person does not hide anything, but is always straightforward, open and honest. Person C, therefore, in spite of the same social rank, expresses respect towards B. Does not thereby C actually stress B’s exceptionality and raise him from the average? Does not C establish a distance between B and all the others, and empower B in that respect?

Equally, one can adopt a joking relation with one’s boss, for example, by saying something like:

4. “Haven’t you babbled it out the other day?”

If one’s boss accepts it, which means, he/she does not get insulted nor does he take any revengeful actions, does not they actually set the common grounds? In principle the provisional correlation still holds. What changes is that the new social relation gets constructed, although only temporarily. With Brown and Levinson this tendency is called reranking of social variables. Situation is an important factor in this respect. As in our previous example of young assistant, one might adopt a polite attitude towards one’s boss when he/she is present, or in the presence of his/her colleagues, while report in a joking manner about the same occurrence when reporting it to the people of one’s own rank.

4. Conclusion

Let me briefly sum up what has been said about the argumentative square. The four topical forms stand for four argumentatively oriented viewpoints or enunciating positions. They are social viewpoints in two senses. In most cases they are common-sense beliefs acknowledged by a community. They can also be more personal (private) beliefs, but as such negotiable: accepted or rejectable within a stretch of communication, which is a good enough reason to call them social.

The four viewpoints seem to have something in common. They seem to establish a relation between the “same” properties. One of the most important Ducrot’s achievements included in this square is that it points to the illusory common nature of these characteristics. This is illustrated already by the contrariety of topoi, but the best illustration is provided by the joking relation. In case of lexical enunciators (that were the primary study case), the two terms of the joking relation can refer to materially the same person and situation. Still, what is seen is not the same at all – one’s attitude towards the person is different as well as is one’s interpretation and understanding of the action performed by him/her. This is possible, because material and social worlds with their respective meanings are not the same. The argumentative square is meant to contribute to the understanding of the latter only. There is another set of terms that is usually associated with the introduced issues, namely truth/falseness. There is no place for this opposition within the argumentative square either. Language usage is about presenting something as true and real, it is about social reality that is necessarily relative to perspectives, enunciating positions, viewpoints. This is a perspective common to constructivistic line of argument. I refer here to Jonathan Potter’s book Representing Reality (1996), where descriptions are seen as human practices and that they could have been otherwise. The relevance is put on “what counts as factual rather than what is actually factual” (Potter 1996: 7).

The model is dynamic in two ways. Every topical form has its argumentative orientation towards a certain conclusion. Since in the case of lexical enunciators the conclusion seems to be the attribution of quality to the person spoken to or about, the chosen topical form can either maintain or attempt to construct a certain type of social relation. Word-choice, understood in this way, plays a vital role in day-to-day stretches of talk, where accounts get constructed.

It was said that topical forms stand for argumentatively oriented viewpoints or enunciating positions. It should now be stressed that the argumentative square primarily illustrates the argumentative orientations of the four topical forms pertaining to two contrary topoi. Each of them can be more or less strongly supported by more then one actual terms or argumentative strings understood, therefore, as degrees on topical scales. For example, the following terms share the same argumentative orientation, but differ in the strength of quality attribution: ‘failure’, ‘defeat’, ‘fiasco’, ‘national tragedy’. The meaning of actual terms is relative to communities and furthermore changes in time and place. Further difficulty with terms is that every term can not so easily be classified as a lexical enunciator, and sometimes an argumentative orientation of what other times the problem proves to be finding different terms for all four orientations. The argumentative square should be understood as a structural analytical model, irrespective of the concrete terms and applicable to any existing topoi. Its shortest definition would therefore read: the argumentative taxonomy of social viewpoints. It serves best for the analysis and demonstration of relativity of those definitions that express contrary accounts of what, extralinguistically, appears to be the “same” situation.

NOTES

i. “Those who work within Greimas’ semiotic perspective say that those four adjectives are the four angles of a square the Greimas square being a sort of adaptation of Aristotle’s logical square. I am not going to go into criticism of those conceptions: I prefer to give you my own way of describing those four adjectives.” (Ducrot 1996: 188)

ii. Polyphonyis a concept that within seemingly uniform notion of a speaker distinguishes three agents, which do not necessarily coincide with one single person: the producer, the locutor and the enunciator.

iii. “it seems to me that in the word itself, as an item of the lexicon, there is a sort of justification of ‘elegance’, – a justification which is like a fragment of discourse written into the word ‘elegant’ I do not think one can understand even the meaning of the word ‘elegant’ without representing elegance as a quality to oneself.” (Ducrot 1996: 88 and 94)

iv. “It is not at all on the grounds of the information provided that you can distinguish the thrifty from the avaricious, it seems to me. The difference is in the attitude you adopt towards the person you are speaking about” (Ducrot 1996: 132)

v. “at times, depending on our discursive intentions, we represent a risk as worth taking and we have consideration for the person who takes it and at others, on the contrary, in our discourse, we represent the fact of taking risks as a bad thing.” (Ducrot 1996: 188)

vi. The point argued might get its full importance with the following example. We can daily read about the so called ‘crises’ around the world, where opposing forces are described in two contrary ways. Since we are not physically or otherwise directly present, our understanding depends solely on articles we read or news we hear. Let me stress that even more important than our own understanding is the understanding of those who decide on the quality and quantity of help or sanctions. Rough categorizations would be as follows: ‘defensive forces’ vs. ‘rebellions’ or ‘repressive forces’ vs. ‘liberators’. The first pair of terms presupposes a justified regime and accordingly portrays those who are against it as unreasonable, while the second pair of terms presupposes the regime to be unfair and, accordingly, considers it to be reasonable and even liberating to act against it. The selection of terms applied is based on reporters’ point of view, their pre-existing attitude towards the regime in question and not actual happenings.

vii. Social distance is ‘a symmetric social dimension of similarity/difference within which S(peaker) and H(earer) stand for the purpose of this act. In many cases (but not all), it is based on an assessment of the frequency of interaction and the kinds of material or non-material goods (including face) exchanged between S and H’. (Brown and Levinson 1978: 76)

viii. Social power is ‘an asymmetric social dimension of relative power, roughly in Weber’s sense. That is, P(H,S) is the degree to which H can impose his own plans and his own self-evaluation (face) at the expense of S’s plans and self-evaluation.’ (Brown and Levinson 1978: 77)

ix. Ranking of imposition is ‘a culturally and situationally defined ranking of imposition by the degree to which they are considered to interfere with agent’s wants of self-determination or of approval’. (Brown and Levinson 1978: 77)

REFERENCES

Brown, P. & S. C. Levinson (1978). Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ducrot, O. (1984). Le dire et le dit. Paris: Minuit.

Ducrot, O. (1996). Slovenian lectures. Ljubljana: ISH.

Mauss, M. (1928). Parentés à plaisanteries. Annuaire de l’École pratique des hautes études.

Potter, J. (1996). Representing Reality: Discourse, Rhetoric and Social Construction. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: SAGE.

Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. (1940). On Joking Relationships. Africa, XIII, No. 3.

Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. (1949). Africa, XIX, No. 3.

Zagar, I.Z. (1995). Argumentation in Language and the Slovenian Connective Pa. Antwerpen: Antwerp Papers in Linguistics 84.