ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Argument Or Explanation? Propositional Relations As Clues For Distinguishing Arguments From Explanations

1. Indicators of argumentative moves

1. Indicators of argumentative moves

In order to investigate which types of words and expressions can be helpful in analyzing argumentative discourse, we started a research project at the University of Amsterdam that concentrates on verbal indicators provided by the Dutch language of the communicative and interactional functions of argumentative moves. Our project aims at making an inventory of potential indicators, classifying their indicative force in terms of the pragma-dialectical model for critical discussion, and describing the conditions that need to be fulfilled for a certain verbal expression to serve as an indicator of a specific argumentative move. The scope of the project is not restricted to indicators of arguments and standpoints, but extends to indicators of all speech acts that can play a part in resolving a dispute.

In carrying out our research, we make use of pragma-linguistic descriptions of connectives and other linguistic elements that can be indicative of aspects of argumentative discourse that are indispensable for an adequate evaluation. In our attempt to apply linguistic descriptions of markers of various kinds of textual relations in the analysis of argumentative discourse, we have encountered a number of obstacles. A major cause of this is that the most prominent approaches of indicators of textual relations are developed from a metatheoretical perspective that is crucially different from the functionalizing and externalizing approach favoured in pragma-dialectics. In addition, there is usually a difference of purpose: linguists are not particularly interested in analyzing argumentative discourse; their distinctions are therefore not geared to solving our problems of analysis.

In this paper, I shall begin by explaining the starting-points of our own pragma-dialectical approach to argumentative indicators. Next, I shall discuss the main problems we have with the relevant linguistic literature. Finally, I shall attempt to demonstrate the fruitfulness of our approach to the analysis of argumentative discourse. In this endeavour, I shall concentrate on the problem of distinguishing arguments from explanations.

2. A pragma-dialectical perspective on the analysis of argumentation

In the pragma-dialectical research programme, argumentation is approached from four basic meta-theoretical starting-points: the subject matter under investigation is to be ‘externalized’, ‘socialized’, ‘functionalized’, and ‘dialectified’ (Van Eemeren et al. 1996: 276-280). What are the implications of these starting-points when applied to the problem of analysing argumentative discourse?

First, functionalization. When analyzing argumentation, the purpose for which the argumentation is put forward is to be duly taken into account. Functionalization can be realized by making use of theoretical instruments from speech act theory, making the speech act the basic unit of analysis, with the propositional and the illocutionary level as its sublevels. By making use of pragmatic insights, the functions and structures of the speech acts performed in argumentative discourse can be adequately described.

Second, socialization. When analyzing argumentation, one should realize that argumentation does not consist in one single individual privately drawing a conclusion, but takes place in the context of a process of joint problem solving. In order to do justice to the fundamentally dialogical character of argumentative discourse, the analysis should be aimed at elucidating the collaborative way in which the protagonist and the antagonist respond to each other’s – real or projected – questions, doubts and objections.

Third, externalization. The analysis should not focus on psychological dispositions or internal thought processes of the people involved in an argument, but on the externalizable commitments created by their performance of speech acts.

Fourth, dialectification. Dialectification is achieved by regimenting the exchange of speech acts directed at resolving a difference of opinion in an ideal model for critical discussion. When analyzing argumentative discourse, this model serves as a point of reference: it clearly indicates what to look for in the analysis. Of course, the analysis must be further justified by referring to the details of the presentation and the context.

Starting from these metatheoretical premises, a pragma-dialectical analysis of an argumentative text aims at identifying all elements that are relevant to the resolution of the dispute and therefore to the evaluation of the discourse. The selection criterion for including elements in the analysis is thus functionality in resolving the dispute. Not all speech acts, however, can be directly related to the overall aim of a critical discussion. In many cases, it needs first to be determined whether there exists a functional relation between certain speech acts before their exact contribution to resolving the dispute can be determined. In such cases, the local relevance of the speech act is to be considered first, before its overall relevance can be at issue.

The reason for this is twofold. First, some speech acts, for example the speech act of argumentation and that of explanation, cannot stand by themselves; they must be in a particular way connected to another speech act by the same speaker. In the case of argumentation, there should exist a relation of support between the argument and a standpoint; in the case of explanation, there is to be an explanatory relation between the explanation and the assertion that expresses the state of affairs that is to be explained (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992: 29). Both argumentation and explanation are complex speech acts, which maintain at a higher textual level a relation with another speech act (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1984: 109).

Second, due to the dialogical character of a critical discussion, many speech acts are only relevant in connection with the speech act to which they react. This is, for instance, the case with speech acts by means of which standpoints and arguments are accepted, agreements are reached on the allocation of the burden of proof, or concessions or criticism are expressed.

According to Van Eemeren and Grootendorst’s definition (1994: 52), an element of discourse is relevant to another element of discourse ‘if an interactional relation can be envisaged between these elements that is functional in the light of a certain objective’. The relevance of an argument to a standpoint consists in it serving as a means to make a standpoint acceptable to the other party, thus making it possible to achieve the interactional aim of convincing the other party. The relevance of an explanation to the state of affairs to be explained is that the explanation makes it understandable for the listener how this state of affairs has come into being.[i]

In the case of reactions to speech acts performed by another party, the relevant connection between the speech acts may be that the one speech act gives an indication as to whether or not the communicative or interactional aim of the other speech act has been achieved – or to what extent. This is, for instance, the case if the second speaker indicates that he accepts – or does not accept – a speech act by the first speaker, or if he indicates that he understands – or fails to understand – a speech act performed by the other speaker. A reaction may also be relevant because it is an attempt to make another speech act acceptable, thus removing the other party’s criticism or doubt, or because it is an attempt to make another speech act understandable, thus solving the other party’s comprehension problems.

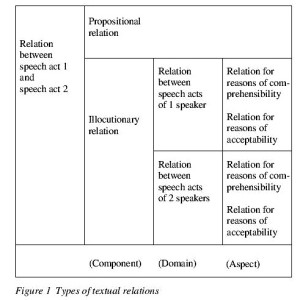

In the pragma-dialectical approach, the notion of relevance is seen as three-dimensional. So far I have only taken account of the domain dimension: to what kind of unit (speech event, stage or other speech act) is a speech act relevant, and of the aspect dimension: what form of relevance is at stake (are the speech acts connected for comprehensibility or acceptability reasons). In considering the relevance of a speech act, justice should also be done to the third dimension, the object dimension. In this endeavour, it is to be established which component of the speech acts is at issue: do we concentrate on the relevance of the propositional content, or of the communicative force? On both these levels, relevance relations may exist. In combination, the metatheoretical starting-points and the ideal speech act model make it possible to give a definition of analytically relevant speech acts and analytically relevant relations between speech acts. Figure 1 gives an overview of the various ways in which elements of an argumentative text may be related to each other.

As far as the indicators of argumentative moves are concerned, it is clear that the clues for analysis should include both indicators of the illocutionary force of individual speech acts and indicators of relations between speech acts. In the linguistic literature, until now the major focus has been on discourse connectives and other indicators of textual relations. What do these linguistic approaches have to offer for the analysis of argumentative discourse?

3. Other perspectives

Research concerned with textual relations and relation-indicating devices is primarily undertaken in the field of text linguistics and discourse analysis. Broadly speaking, two major types of approach to indicators of textual relations can be distinguished. First, top-down approaches, in which textual relations are classified in terms of a limited number of theoretical notions (‘primitives’), and subsequently an attempt is made to determine which connectives can be used to mark these relations. Among the representatives of this approach are Mann and Thompson (1988), Sweetser (1990) and Sanders (1992, 1997). In the second type of approach, the bottum-up approach, first an inventory of indicators is made and then it is attempted to find out (in a pretheoretical way), by analysing texts or by using substitution tests, how these indicators can be used. As a result, a set of features comes up ‘inductively’ that is necessary for giving a systematic description of the various indication devices. Representatives of this type of approach are Knott and Mellish (1996) and Schiffrin (1987).[ii]

In our attempt to make use of the semantic and pragmatic descriptions of argumentative and other types of connectives, we encountered two major types of problem: incompatibilities with the pragma-dialectical meta-theoretical premises and lack of relevance of the distinctions to problems of analysis. Let me briefly illustrate these problems.

Many of the prominent approaches to textual relations are only partly functionalized, for example, Mann & Thompson’s, Sanders’ and Sweetser’s approach. In principle, these authors do all make use of concepts from speech act theory and they seem to favour a functional approach. Seen from a pragmatic perspective, their approaches suffer nonetheless from a number of inconsistencies. They all make a distinction between relations between states of affairs in reality, and pragmatic or illocutionary relations. They do not make a hierarchical distinction between relations at the propositional and relations at the illocutionary level. Relations between states of affairs, which in a speech act perspective would be regarded as propositional relations, are treated as functioning on a par with illocutionary relations. For this reason, it often goes unnoticed that relations between two speech acts can exist on two levels at the same time. This is, for instance, the case in an argument-standpoint relation at the illocutionary level that is based on a causal relationship at the propositional level.[iii]

I shall illustrate the problem by discussing some distinctions made in the Rhetorical Structure Theory of Mann and Thompson (1988). At first sight, this theory seems to correspond nicely with the pragma-dialectical approach. Mann and Thompson consider their theory to be a functional theory of text structure and they think that it can be used as a tool for the analysis of a wide range of text types. They distinguish a large number of textual relations varying in the effect they intend to achieve in the reader. For each relation between two text spans, called the ‘nucleus’ and the ‘satelite’, they formulate a number of constraints reminiscant of the felicity conditions for speech acts.[iv] The textual relations are divided into two groups, ‘subject matter’ relations and ‘presentational’ relations:

Subject matter relations are those whose intended effect is that the reader recognizes the relation in question; presentational relations are those whose intended effect is to increase some inclination in the reader, such as the desire to act or the degree of positive regard for, belief in, or acceptance of the nucleus (1988: 257).

In their definition of subject matter relations, the only intended effect Mann and Thompson mention is the communicative effect of recognizing the relation between the propositional contents of the related speech acts. They do not give an account of the illocutionary purpose, or interactional goal, for which a propositional relation is employed by the writer. This means that the analyses offered by Mann and Thompson are only partially functional.

In other approaches, the lack of externalization is problematic. Sweetser’s (1990) multiple-domains theory, currently popular among pragma-linguists, is a good example. According to Sweetser, sentences that contain ‘causal’ conjunctions, such as ‘therefore’, ‘since’ and ‘so’, can be given different readings, depending on the type of causality that is at issue. The relationship between the conjoined clauses can be based on

(a) real-world causality,

(b) epistemic causality or

(c) speech act causality. Sweetser (1990: 77) gives the following examples:

(1a) Real-world causality: John came back because he loved her

(1b) Epistemic causality: John loved her, because he came back.

(1c) Speech act causality: What are you doing tonight, because there’s a good movie on.

From Sweetser’s examples, it becomes clear that the relation of epistemic causality must be similar to the relation between a standpoint and an argument for the truth or acceptability of its propositional content. The problem is, however, that Sweetser gives an internalizing definition of the epistemic relation which creates a fundamental difference between the epistemic causal relation and the argumentative relation.[v] Sweetser does not situate the epistemic relation at the speech act level, but at the level of the speaker’s thought processes. In her analysis, example 1b is seen as a statement about the writer’s conclusions and how they were reached. Knott and Mellish (1996: 153) point out that ‘an account is missing of how an argumentative text […] achieves a rhetorical effect on the reader – how it persuades the reader’ of the conclusion that is presented by the writer. They concede that there may be contexts where Sweetser’s analysis of epistemic relations is preferable, for instance when dealing with writers who are simply expressing their own chain of reasoning out loud for scrutiny by a reader whose authority they accept, but they do not consider this a prototypical use of argumentative relations (Knott & Mellish 1996: 154).

The internalizing approach underlying the concept of epistemic causality runs counter to the pragma-dialectical starting-point of externalization, which requires the argumentation theorist to concentrate on the speech acts performed and the externalized or externalizable commitments of the arguer rather than on the beliefs and inferences involved in the reasoning process of drawing a conclusion. A different type of problem concerns the applicability of the distinctions made in the linguistic literature to the analysis of argumentation. Sometimes the definitions of textual relations are not differentiated enough for practical purposes. Often all inference-relations are brought together under the general heading of ‘causal relation’. Then it is not possible to make a distinction between establishing a causal connection, describing a causal relation, and making use of a causal relation in an explanation or in an argument.

There are authors who make all kinds of subdistinctions, but it is often not obvious that they are relevant for analytical purposes. Sometimes it is even difficult to discover to which subcategory or subcategories the argumentative relation belongs. In the Rhetorical Structure Theory by Mann and Thompson, for instance, it is hard to determine which relations are to be regarded as argumentative. Apart from obvious candidates, such as the presentational relations ‘Motivation’, ‘Evidence’ and ‘Justify’, there are subject-matter relations such as ‘Cause’ that could or could not be used argumentatively. The same is true of ‘Solutionhood’: the intended effect of this relation is that the reader recognizes that one part of the text presents a solution to a problem presented elsewhere. Such a solution, however, can be presented for descriptive purposes, but also for argumentative purposes, as in pragmatic argumentation.

4. Distinguishing arguments from explanations

The distinctions made in the linguistic literature are not a good starting-point for solving problems of analysis of argumentative discourse such as distinguishing arguments from explanations. Due to the failure to distinguish systematically between relations at the propositional level and relations at the illocutionary level, an important source of clues is disregarded. By linking relations at the propositional level systematically with relations at the illocutionary level, as propagated in the pragma-dialectical approach, it is possible to obtain information that is crucial to the identification of the speech acts of arguing and explaining.

Whereas there are no restrictions on the propositional content of a standpoint supported by an argument, both the propositional content of the explained statement and that of the explaining statements are bound to certain conditions. These conditions can be deduced from the characteristics of the speech act of explaining.[vi] They make clear that a piece of reasoned discourse can only be an explanation if the reasoning is at the propositional level based on a causal relation, not on a symptomatic relation or an analogy. Moreover, the causal relation should be construed in such a way that the effect is mentioned in the explained statement and the cause in the explaining statement, instead of the other way around. In addition, the explained statement should contain a descriptive proposition, not an evaluative or inciting one. This proposition should refer to a factual state of affairs, not to a state of affairs that is still to be realized. Since an explanation must be based on a causal relation, identifying the type of relation the reasoning is based on at the propositional level is a crucial step in the analysis. Indicators of propositional relations are therefore an important source of clues for distinguishing arguments from explanations.[vii]

My conclusion is that the functionalizing speech act perspective inherent in the pragma-dialectical approach creates a better starting point for making a systematic inventory of linguistic clues at the different hierarchical levels of argumentative discourse than the pragma-linguistic approaches proposed by others. Particularly, by combining pragmatic analyses of the contextual preconditions for performing the speech acts of arguing and explaining with the use of pragma-dialectical analytical instruments, a sound basis can be created for using linguistic insight in a well-founded and systematic way.

NOTES

i. In the context of a critical discussion, realizing the communicative aim of making it understandable for the listener how a certain state of affairs came into being, can be a means to further the achievement of an interactional aim that is associated with one or more other illocutionary acts performed in the discussion.

ii. In principle, the top-down approaches are more closely related to the pragma-dialectical approach to argumentation analysis in that they start from a theoretical stance taken toward the phenomena, and thus can be seen as ‘a priori’ approaches instead of inductive a posteriori apporaches. The pragma-dialectical approach is a priori in the sense that it begins with a model of critical discussion (Van Eemeren et al. 1993: 52-52). Nonetheless, the bottum-up approaches are also relevant to our research, since they often provide detailed descriptions of the ways in which various types of indicators may be used.

iii. Sanders (1997: 123) does acknowledge that a propositional and and illocutionary relation may exist at the same time, but he claims this is not necessarily the case, and regards the propositional relation as of secondary importance.

iv. Apart from relations consisting of a nucleus and a satelite, Mann and Thompson also distinguish ‘multinuclear’ relations (1988: 247). The large majority of relations, however, holds between a nucleus and a satellite.

v. Even if Sweetser’s epistemic causal relation were to be reinterpreted as a relation between speech acts, it would still not fully satisfy the concept of argumentation. Sweetser’s epistemic causal-conjunctions always have factual conclusions: certain knowledge ‘causes’ the speaker to conclude that something is true. There is no place for argumentation in support of evaluative or inciting conclusions.

vi. My overview of distinguishing features of arguing and explaining is based on Houtlosser’s (1995: 226-227) analysis of the speech act complex of giving an explanation and van Eemeren and Grootendorst’s (1984: 44-45, 1992: 31) analysis of the complex speech act of argumentation.

vii. In the case of argumentation, indicators of propositional relations are called ‘indicators of the argumentation scheme’.

REFERENCES

Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst (1984). Speech acts in argumentative discussions. A theoretical model for the analysis of discussions directed towards solving conflicts of opinion. Dordrecht/Cinnaminson: Foris Publications, PDA 1.

Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, communication and fallacies. A pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst (1994). Relevance reviewed: the case of argumentum ad hominem. In: F.H. van Eemeren & R. Grootendorst (Eds.), Studies in pragma-dialectics (pp. 51-68, Ch. 5). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Eemeren, F.H. van, et al. (1993). Reconstructing argumentative discourse. Tuscaloosa/London: University of Alabama Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, et al. (1996). Fundamentals of argumentation theory. A handbook of historical backgrounds and contemporary developments. Mahwah (N.J): Lawrence Erlbaum.

Houtlosser, P. (1995). Standpunten in een kritische discussie. Een pragma-dialectisch perspectief op de identificatie en reconstructie van standpunten. Ifott: Amsterdam [Standpoints in a critical discussion. A pragma-dialectical perspective on the identification and reconstruction of standpoints (with a summary in English)].

Knott, A. & C. Mellish (1996). A feature-based account of the relations signalled by sentence and clause connectives. Language and Speech, 39, 143-183.

Mann, W.C. & S.A. Thompson (1988). Rhetorical structure theory: toward a functional theory of text organization. Text, 8, 243-281.

Sanders, T. (1992). Discourse structure and coherence. Aspects of a cognitive theory of discourse representation. Diss. Katholieke Universiteit Brabant.

Sanders, T. (1997). Semantic and pragmatic sources of coherence: On the categorization of coherence relations in context. Discourse Processes, 24, 119-147.

Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sweetser, E.E. (1990). From etymology to pragmatics. Metaphorical and cultural aspects of semantic structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.