ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Must Arguments Be Explicit And Violent? A Study Of Naïve Social Actors’ Understandings

Argumentation is one way of settling differences, and it is often prized by theorists as an alternative to violence and other less intellectual ways of managing conflicts (e.g., Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969; Ehninger & Brockriede 1963). We academics have no difficulty at all in seeing that arguing is a dramatically different sort of thing than physical fighting. The clarity with which we see this, however, may not match the perceptions of our students, or the public at large. This paper explores the possibility of perceptual connections between arguing and violence among ordinary people.

Argumentation is one way of settling differences, and it is often prized by theorists as an alternative to violence and other less intellectual ways of managing conflicts (e.g., Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969; Ehninger & Brockriede 1963). We academics have no difficulty at all in seeing that arguing is a dramatically different sort of thing than physical fighting. The clarity with which we see this, however, may not match the perceptions of our students, or the public at large. This paper explores the possibility of perceptual connections between arguing and violence among ordinary people.

1. Literature Review

At the 1997 Alta meeting, we reported some intriguing results about naive social actors’ understandings of argument (Benoit & Hample 1997). We had asked them to keep diaries about conflicts that they had avoided or cut short. But in reading the diary accounts, we frequently found ourselves wondering what could possibly have been avoided or cut off, because the narratives seemed very complete to us. After a number of re-readings, we decided that, unlike argumentation scholars, our respondents assume that there is a “violence slot” in the development of face to face arguments, and if nothing physically aggressive happened, the argument had not moved through all its potential phases. We also realized that they seemed not to count something as an argument at all if the central claim-and-disagreement were not explicit. That is, if no one had gotten around to announcing the disagreement, they thought the interaction was unfinished.

We followed that study up with a larger one, still using data from conflict diaries, but undertaking systematic coding of the accounts instead of a qualitative reading of them (Hample, Benoit, Houston, Purifoy, VanHyfte, & Wardwell 1998). We found that explicitness and destructiveness of the arguments in the diaries were correlated at r = .80, which is extraordinarily high. In other words, the more explicit (i.e., argument-like) a conflict was, the more destructive it was. For our respondents, arguments seem not to be alternatives to violence; instead, they appear to be companions to fights, or causes of them, or parts of them, or perhaps even essential to their nature.

That we were surprised by this is surely due more to our own perceptual blinders than anything else. Earlier work has shown that people are definitely fearful that their arguments will get out of hand, in spite of their earnestly cooperative intentions (Benoit 1982). Trapp (1990) documented a tendency for arguments to escalate into verbal aggression, and Infante, Chandler, and Rudd (1989) suggest that these out-of-control arguments may trigger spouse abuse. When naïve actors are asked to list the specific actions that may take place in a face to face argument, many of them specify one or more slots for threats and physical violence (Hample, Dean, Johnson, Kopp, & Ngoitz 1997). Gilbert (1997) explores the idea that both the standard practices and standard theories of argument are competitive, agonistic, and masculine. Somehow, though, our own commitments to argumentation as an alternative to violence, as a rational path to conflict management, as an interactive ideal in the face of conflicting wants, made us see all these negative indications about the nature of argument as being nothing but minor perceptual distortions, failures to understand the real nature of arguing. We continue to hold our original commitments, but we now feel a greater need to acknowledge, understand, and respect what non-specialists think about all this.

Let us begin by asking, What had to be so, in order for our diary studies to have come out the way they did? Recall that the key result, the one exercising us here, is that explicitness and destructiveness of arguments are very nearly synonymous for our informants. We understand explicitness to index the recognition that the encounter actually is an argumentative one. When the disagreement is unstated or the conflict merely implied, our diarists seemed to think that an argument hadn’t quite happened, that they were describing a conversation one could simply walk away from, without any argumentative commitments having been made. A clearly identifiable argument – an explicit one – was also a destructive one. Feelings would be hurt, bodies might be threatened, relationships could be put at risk.

Two explanations for this identity between explicitness and destructiveness occur to us. (1) This is the way the world is. People accurately and representatively reported their arguments to us. All, or virtually all, arguments really do implicate violence or its immediate possibility. (2) People have the prejudice that arguments are typically destructive. Therefore, whenever they identified something as being appropriate for a diary entry – perhaps as being a paradigm case of arguing – they had already judged that the episode had hurtful potential. Thus, destructiveness was a qualifying feature for something to be reported to us.

We have little to say here about the first possibility. We know that it is not so theoretically, because arguments can be productive and emotionally positive experiences. The equivalence of arguing and hurting may well be an accurate summary of some people’s personal experience with conflicts (Hample, in press), but this is not the case for everyone. The design of the study we report here controls for this first possibility by making it inoperative in our stimulus materials.

The second possibility is the one that mainly concerns us. On reflection, we believe that explanation (2) could have two different causes. The first is that people’s “destructiveness prejudice” is as deeply seated as some other deleterious stereotypes. Whenever they see an argument, they think they are also seeing danger of some sort. This might be a defensive reaction against the known possibility of hurt, or might reflect a negativity bias in perceiving others and their actions (see Coovert & Reeder 1990). The second possible cause is that people simply misunderstand what is meant by “argument” (or, less presumptuously, that naïve actor’s definitions are just different than ours), and that they can be educated toward a view that more closely resembles the academic one.

Our research strategy is a fairly simple one, at bottom. We created a series of argument vignettes that were each explicit or implicit, destructive or constructive. Then we asked respondents to rate these on scales that would reflect perceptions of explicitness and destructiveness. By providing these scenarios ourselves, and systematically varying the two key variables, we removed possibility (1) from consideration. Even if the world nearly always does generate explicit and damaging arguments, our design doesn’t.

We anticipate two possible sorts of outcomes, which correspond to the two possible reasons for explanation (2). If our respondents continue to see explicitness and destructiveness as highly correlated (even though they have been manipulated to be orthogonal in our design), we will be confident that we are observing a persistent perceptual bias. Anticipating the possibility of this outcome, we included tests of a trait connected to conflict perceptions, the tendency to take conflict personally (TCP) (Hample & Dallinger 1995). Should this perceptual effect appear, the TCP data might be a first step in explaining its etiology. If, on the other hand, the correlation between explicitness and destructiveness disappears, we will conclude that our diary respondents were simply working with a different definition of “argument,” one that will not be unusually difficult to change through standard instruction; that is, the earlier association was due to their category “argument,” rather than to their perceptions or biases about it. Our hope is that the correlation dissipates, but we have no grounds for predicting whether it will or not, so we offer no formal hypothesis.

2. Method

2.1. Respondents

Data were provided by 303 students enrolled in undergraduate communication classes at the first author’s institution. 53% were male, and the sample’s mean age was 20.3 years. The sample was distributed across the four undergraduate years, with 20-30% belonging to each class.

2.2 Procedure

Respondents were given a booklet. After giving consent, they answered some demographic questions and filled out the trait version of the Taking Conflict Personally scale (Hample & Dallinger 1995). The respondent then read a brief argument scenario, was instructed to imagine himself/herself participating in the interaction, and then filled out several scales about the imagined interaction. Then each respondent repeated these last procedures with a second scenario. After finishing, students were debriefed.

2.3. Scenarios and Instructions

We wrote 16 scenarios, which were randomly distributed throughout the sample. We based them, as far as we could, on actual reports from the diary studies. The scenarios were labeled “possible interactions” for respondents. These vignettes were designed to represent several conditions. Half were explicit, and half implicit; half were constructive, and half destructive; half involved an argument with a roommate, and half with a romantic partner. Each condition was represented twice in the collection of scenarios, yielding a 2x2x2x2 (explicit x constructive x relationship x replication) design.

To ease the understanding of our results, please notice that “replication” will always refer here to a different example of, say, an explicit, constructive, roommate argument. This is easily confused with the fact that each respondent read two scenarios; these will be called scenario (or vignette) 1 and 2. The “replications” have nothing to do with the scenario series, so that the second explicit/constructive/roommate argument was read first just as often as it was read second.

Each scenario was preceded by these instructions: “Please read the brief description of a possible interaction you might have. Pause for a moment to visualize it, and to imagine you’re actually in it. How would you react? What would you do or say? How would you feel? After you’ve taken a moment to do that, please respond to the items we’ve provided, according to how they apply to the interaction we’ve supplied.” Here is an example of one of the scenarios, instantiating a destructive, not-explicit argument with a romantic partner: “You have a long distance relationship. You haven’t seen your romantic partner for a month and when s/he comes to visit, you go out with some of your friends. When you are out dancing, your romantic partner trips you, as a sort of bad joke.” Following the scenario, 16 items (described below) were provided, along with standard instructions on how to respond.

2.4. Instruments

Taking Conflict Personally (TCP) was measured by means of a 37 item Likert instrument designed to produce scores on six subscales (Hample & Dallinger 1995). Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales are as follows: direct personalization, .82 (omitting item 1); persecution feelings, .74; stress reactions, .65 (omitting item 27); positive relational effects, .74; negative relational effects, .79; and like/dislike valence, .75 (omitting item 20).

Constructiveness and explicitness were measured by eight semantic differential items each. These items were generated for this study. They are as follows (where R indicates reverse scoring, and item numbers are shown).

Constructiveness:

– constructive/destructive [1],

– good/bad [2],

– harmful/beneficial [4R],

– helpful/damaging [8],

– a controlled interaction/not a controlled interaction [10],

– would harm our relationship/would not harm our relationship [12R],

– violent/nonviolent [13R],

– positive/negative [15].

Explicitness:

– explicitly an argument/not explicitly an argument [3],

– hid my feelings/ expressed my feelings [5R],

– a conflict/not a conflict [6],

– didn’t give reasons for what I said or did/did give my reasons for what I said or did [7R],

– disagreement between us not apparent/disagreement between us was apparent [9R],

– I communicated clearly/I didn’t communicate clearly [11],

– said what I thought/did not say what I thought [14], and

– everything would be out in the open/everything would not be out in the open [16].

We ran a series of exploratory factor analyses on these scales. Since each respondent filled out the scales for two scenarios, we conducted separate factor analyses for each scenario series. The destructiveness items performed more or less as expected, loading together for both scenario series, except that item 15 had to be dropped. On analysis, the explicitness items proved to be measuring two different things. The first, which we will continue to call explicitness, consists of items 3, 6, and 9. The other, which in hindsight appears to be assessing the presence or absence of full disclosure, we will call disclosiveness. We therefore formed scales, as follows.

The constructive/destructive scale consists of items 1, 2, 4, 8, 10, 12, and 13, and produces Cronbach’s alphas of .89 and .90 for the two scenarios. The explicitness measure includes items 3, 6, and 9, with alphas of .71 and .76. The disclosiveness scale consists of items 5, 7, 11, 14, and 16, and yields alphas of .84 and .87. The directions of scoring were such that a high score on the first variable shows that respondents felt the conflict would be destructive, a high score on the second means that respondents thought the conflict would be implicit, and a high score on the third indicates nondisclosiveness.

3. Results

3.1. The Associations Among Destructiveness, Explicitness, and Disclosiveness

Perceived destructiveness and explicitness were correlated with one another. The first scenario series produces r = -.48 (p<.001), and the second r = -.51 (p<.001). These results replicate both Benoit and Hample’s (1997) and Hample, Benoit, et al.’s (1998) findings, because both these papers report an association between destructiveness and explicitness, as in the present report. Perceived destructiveness and nondisclosiveness were also correlated with one another. In the first scenario, r = .35 (p<.001), and in the second, r = .24 (p< .001). Finally, the associations between disclosiveness and explicitness are r = .06 (ns) for the first series of vignettes, and r = .33 (p<.001) for the second.

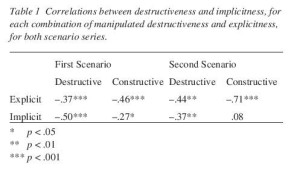

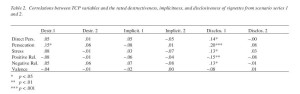

The two previous studies examined respondents’ argument diaries, and the researchers observed a strong tendency for destructiveness and explicitness to co-occur in those accounts. The systematic manipulation of destructiveness and explicitness in the present design guards against such co-occurence, but therefore produced a systematically different sample of arguments to be rated. Consequently, we also examined the destructiveness-explicitness correlations in the present study after dividing the data set by manipulated destructiveness and explicitness. Table 1 displays the correlations between perceived destructiveness and implicitness, by manipulation condition.

Table 1 Correlations between destructiveness and implicitness, for each combination of manipulated destructiveness and explicitness, for both scenario series.

The overall destructive/explicit correlations of -.48 and -.51 reported above are obviously depressed by the constructive/implicit conditions, which would probably have been rarest in the diaries data. The destructive/explicit conditions are perhaps most representative of the diaries data. This manipulation produces a moderate association between perceived destructiveness and perceived explicitness. The overall results, combined with the correlations subdivided by manipulation condition, indicate that our respondents persist in associating explicitness and destructiveness, but not at the exceptionally high levels reported for diarists (Hample, Benoit, et al. 1988). When these two variables are manipulated to be orthogonal in the stimulus set, as was done here, the destructiveness/explicitness correlation is somewhat reduced, but still clearly evident.

These results are supportive of explanation 2, because the design temporarily eliminates the possibility that the world supplies only explicit, damaging arguments to people.

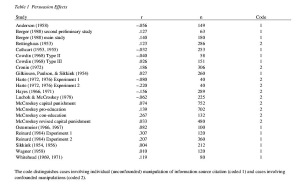

Taking Conflict Personally

The TCP scales were correlated with respondents’ ratings of the destructiveness, implicitness, and nondisclosiveness of each scenario.

Since each person responded to two vignettes, each pair of variables produces two correlations. Results appear in Table 2. The table shows few significant results, and little consistency among them. Since the scenarios were randomly distributed, and each occurred as often as the first stimulus as it did the second, the differences between the pairs of columns can only be attributed to some sort of fatigue effect. The table gives no evidence that there is any connection between people’s trait TCP and their estimate that the argument would have been destructive or explicit, and weak evidence of a small connection between TCP and estimates of disclosiveness (such that people high in TCP may be somewhat less likely to be disclosive). In short, TCP appears to have little effect on one’s perception of an argument’s destructiveness, explicitness, or disclosiveness.

Table 2. Correlations between TCP variables and the rated destructiveness, implicitness, and disclosiveness of vignettes from scenario series 1 and 2.

3.3. Perceived Destructiveness, Explicitness, and Disclosiveness as Dependent Variables

This set of results clears the way for an examination of whether the manipulations (destructiveness, explicitness, relationship with other, and replication) had effects on perceived destructiveness, explicitness, or disclosiveness. We therefore undertook 2x2x2x2 ANOVAs, doing each analysis twice, once for the respondents’ first vignette, and once for the second.

When perceived destructiveness is the dependent variable, the first vignette yields several significant results. Significant main effects appear for the constructiveness manipulation (F = 111.4, df = 1, 282, p .001; the destructively intended scenarios have higher means, as expected, 22.7 versus 16.5), the explicitness manipulation (F = 5.4, df = 1, 282, p .05; the implicit arguments are rated as more destructive, 20.5 versus 18.8), relationship with other (F = 19.4, df = 1, 282, p .001; the roommate conflicts are more destructive than those with romantic partners, 21.0 versus 18.6), and replication (F = 4.4, df = 1, 282, p .05). The only significant interactions involved the replication manipulation, and are therefore of no substantive interest here.

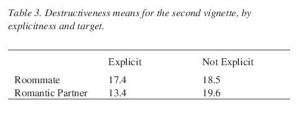

The analysis was repeated for the respondents’ second imagined interaction, with similar results. Significant main effects appear for the constructiveness manipulation (F = 122.0, df = 1, 281, p .001; the destructively intended vignettes are seen as more destructive, 24.4 versus 17.2), the explicitness manipulation (F = 24.1, df = 1, 281, p .001; the implicit interactions are again more destructive, 22.8 versus 19.3), and the relationship with other (F = 11.3, df = 1, 281, p .001; the roommate conflicts are again seen as more destructive, 22.3 versus 19.8), but not for replication (F 1). The only significant interaction not involving the replication factor is a two-way interaction between manipulated explicitness and relationship with other (F = 5.1, df = 1, 281, p .05). The means, displayed in Table 3, indicate that the effects of explicitness are strongly influenced by relationship: the destructiveness of the inter-action is greatest when romantic partners have implicit conflicts, and is most manageable when romantic partners have explicit arguments.

The destructiveness results are nicely consistent. The main effects for constructiveness indicate merely that the manipulation worked. The main effects indicate that arguments with one’s roommate (compared with one’s romantic partner) are felt to be more dangerous, as are implicit conflicts. This last finding is inconsistent with the positive association between perceived destructiveness and perceived explicitness, and raises the question of whether the respondents and experimenters are viewing explicitness in the same way.

Similar analyses of variance were done, using explicitness as the dependent variable. Results for the first scenario series are as follows. Significant main effects appear for replication (F = 7.0, df = 1, 284, p 01) and destructiveness (F = 50.2, df = 1, 284, p .001, with means indicating that the destructively intended vignettes are seen as more explicit, 7.2 versus 9.4). Argument partner has no effect (F = 1.0, df = 1, 284, ns), and neither does manipulated explicitness (F 1). This last results points to a manipulation failure. The only significant interaction not involving the replication factor is a two-way between argument partner and destructiveness (F = 6.1, df = 1, 284, p .05; means indicate that destructiveness had the least effect on romantic partners, with their explicitness means showing less difference than those of roommates).

The second scenario produced comparable results. Significant main effects appear again for replication (F = 4.8, df = 1, 281, p .05) and destructiveness (F = 122.1, df = 1, 281, p .001, with means again showing that the destructively intended vignettes are seen as being more explicit, 6.5 versus 9.9). The second scenario series also yields a significant effect for argument target (F = 15.9, df = 1, 281, p .001, with means indicating that the roommate conflicts are seen as more explicit, 7.6 versus 8.8). Here, too, however, we obtain the disappointing failure to confirm the manipulation, with the explicitness effect being insignificant (F = 1.9, df = 1, 281, ns, although the means are in the correct order, 8.0 versus 8.4). The only significant interaction effect not involving the replication factor is between explicitness and destructiveness (F = 4.4, df = 1, 281, p .05; means show that the greater perceived explicitness for destructive arguments is more marked for explicitly intended episodes).

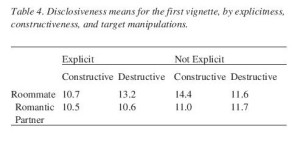

Finally, we undertook parallel analyses, using perceived disclosiveness as the dependent variable. For the respondents’ first scenario, the only significant main effects are for relationship with other (F = 8.0, df = 1, 284, p .01; romantic partner arguments are seen as more disclosive, 12.4 versus 11.0) and replication (F = 7.2, df = 1, 284, p .01). The main effect for explicitness was not significant (F = 2.01, df = 1, 284, p = .15), although the means are the direction of explicit arguments having fuller disclosure, 11.2 versus 12.1. Several significant interactions not involving the replication factor appear. A two-way interaction between manipulated constructiveness and manipulated explicitness is significant (F = 4.2, df = 1, 284, p .05), as is a three-way interaction involving constructiveness, explicitness, and relationship with other (F = 7.3, df = 1, 284, p .01).

Table 4. Disclosiveness means for the first vignette, by explicitness, constructiveness, and target manipulations

The means illustrating this three-way interaction (and, of course, including the information necessary to see the two-way interaction), are in Table 4. These means indicate that the most disclosive arguments are those with romantic partners. For roommates, the arguments are seen as disclosive when they were intended to be explicit and constructive, and are seen as nondisclosive when they were intended to be implicit and constructive.

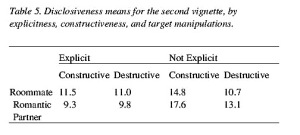

The parallel analysis on the second vignette for each respondent produced these results. Significant main effects appear for constructiveness (F = 11.1, df = 1, 282, p .001; destructive arguments are more disclosive, 11.2 versus 13.3), explicitness (F = 36.4, df = 1, 282, p .001; explicitly intended scenarios are seen as more disclosive, 10.4 versus 14.0), and replication (F = 14.1, df = 1, 282, p .001). The only significant interactions not involving the replication factor are between the constructive and explicitness manipulations (F = 12.6, df = 1, 282, p .001), and between the explicitness manipulation and relationship with other (F = 13.4, df = 1, 282, p .001).

The means for these interactions are in Table 5. These means indicate that the most disclosively perceived arguments are those that were supposed to be implicit and constructive for romantic partners. The least disclosively perceived ones are those that were intended to be explicit and between romantic partners. The results for romantic partners are the most variable, suggesting that these relationships involve more exaggeration of (or, perhaps, more salience for) the manipulations.

Table 5. Disclosiveness means for the second vignette, by explicitness, constructiveness, and target manipulations

The results for perception of disclosiveness are not entirely consistent. The two scenarios do not produce quite the same pattern of significant results, in spite of their containing the same scenarios in the same proportions. Results suggest that arguments with romantic partners are seen as having fuller disclosure, and that destructive arguments are also seen the same way, although these effects are qualified by interactions. When compared to the explicitness results, these findings suggest that we may have been somewhat more successful in manipulating disclosiveness than explicitness, in spite of having intended only to vary the latter.

4. Discussion

In this final section, we wish to discuss our leading results, and then to return to the issues that stimulated the study.

Perhaps the two most interesting empirical findings in this paper are that (1) destructiveness and explicitness are positively correlated, and (2) roommate conflicts are more destructive than conflicts with romantic partners. Both findings deserve some comment.

First, let us consider the destructive-explicit association. As in the diary studies, our respondents made a clear connection between the explicitness of an argument and its inherent danger. The diary data (Hample, Benoit, et al. 1998) produced a stronger correlation than appeared here, and the effectiveness of this study’s explicitness manipulation is open to question. Still, this investigation both replicates and triangulates the earlier finding. The chief benefit of the present design is that our attempt to vary destructiveness and explicitness orthogonally means that the earlier findings cannot be explained by our instructions to diarists, or by their search for paradigm cases of face to face argument.

We were faced with an unanticipated complication in our study of the association between destructiveness and explicitness, however, and this centered around our own understanding of explicitness. We generated a number of scales to reflect our own construct for explicitness: that an episode would have clear disagreement, that it would obviously be mutually framed as an argument, that both people would speak their minds, and that they would put their claims and counter-claims on the table. Our respondents had a more sophisticated view of all this, however, and saw two things being indexed in those scales: the explicitness and obviousness of the episode-as-argument, and the degree to which our respondents would have been willing to express their true thoughts and feelings. Dividing this into two separate scales was not a problem, of course. The problem occurred when we tried to translate our understanding of explicitness into varying scenarios. The explicitness manipulation did pretty much work as far as disclosiveness was concerned, but it did not produce supportive means on the measure of perceived explicitness. This necessarily qualifies all our findings relating to the so-called manipulation of explicitness.

On reflection, we now think that it may be important to consider that some sorts of argument may involve a failure to self-disclose, an unwillingness to expose one’s thoughts and feelings to the other. This might be thought dangerous and destructive in and of itself, and might also be seen as symptomatic of an already damaged interaction or relationship. Thus, arguments in which participants do not say what they think are perceived as bad, harmful, and damaging, but this may have less to do with recognizing whether the episode is an argument, than with the view that a non-disclosive interaction is already fundamentally flawed. So a nondisclosive argument might indicate damage, rather than cause it.

The second empirical finding of note is that roommate conflicts were rated as more fraught with danger than romantic conflicts. One would suppose that the stakes would be higher with romantic partners, making intense hurt and extreme danger more possible in that setting. But roommates evoked more apprehension here. We wonder if two factors – other than the stakes – might be at work here. First, in our sample, people were living with their roommates, but not necessarily with their romantic partners. One can simply go home after a date, but still has to sleep in the apartment. This would make conflicts less avoidable for roommates, and so more dangerous. Second, the intimacy of a romantic relationship may well have generated norms for handling conflict, in part because of the greater value placed on the relationship by both parties. Table 3 showed an interaction effect, such that implicit arguments were rated as particularly destructive for romantic couples. Even though intimate partners may have better developed conflict management norms, ambiguous episodes can be threatening, and the high stakes may exacerbate this more than for roommates.

Perhaps the most substantial issue raised by our results is whether they are compatible with those of Benoit and Hample (1997) and Hample, Benoit, et al. (1998). The present findings replicate the earlier ones. The connection between destructive potential and explicitness was unmistakable in all these investigations. In the present study, we created a stimulus set that destroyed any possible natural connection between explicitness and destructiveness. This design strategy permitted us to test whether the earlier result was due to the peculiarity of the argument sample we were dealing with. In fact, the clear association between perceived destructiveness and perceived explicitness does not appear to depend on the argument sample, and this considerably improves our confidence in the finding. However, it also points toward the more troubling explanation for the association, namely, that people have a fundamental, stereotyped pessimism about arguments.

This leads us toward several conclusions regarding our title question, Must arguments be explicit and violent? (1) Left to their own devices, and asked to identify clear arguments from their lives, people will report explicit, dangerous episodes. (2) Given a systematically neutral stimulus set, people still see a strong connection between explicitness and destructiveness. (3) This derives from their perception of what an argument is, and this view is one argumentation scholars wish to alter. (4) Therefore, we should worry about our students’ most basic understandings of argumentation, and not take for granted that they believe us when we tell them that arguments are alternatives to violence.

REFERENCES

Benoit, P. J., & Hample, D. (1997, July). The meaning of two cultural categories: Avoiding interpersonal arguments or cutting them short. Paper presented at the Summer Conference on Argument, Alta, UT.

Benoit, P. J. (1982, November). The naive social actor’s concept of argument. Paper presented at the Speech Communication Association, Louisville, KY.

Coovert, M. D., & Reeder, G. D. (1990). Negativity effects in impression formation: The role of unit formation and schematic expectations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 26, 49-62.

Ehninger, D., & Brockriede, W. (1963). Decision by Debate. New York: Dodd.

Gilbert, M. A. (1997). Coalescent Argumentation. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hample, D. (in press). The life space of personalized conflicts. Communication Yearbook.

Hample, D., & Dallinger, J.M. (1995). A Lewinian perspective on Taking Conflict Personally: Revision, refinement, and validation of the instrument. Communication Quarterly 43, 297-319.

Hample, D., Dean, C., Johnson, A., Kopp, L., & Ngoitz, A. (1997, May). Conflict as a MOP in conversational behavior. Paper presented to the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Montreal.

Infante, D. A., Chandler, T. A., & Rudd, J. E. (1989). Test of an argumentative skill deficiency model of interspousal violence. Communication Monographs 56, 163-177.

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argument (trans. J. Wilkinson & P. Weaver). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Trapp, R. (1990). Arguments in interpersonal relationships. In: R. Trapp & J. Schuetz (Eds.), Perspectives on Argumentation: Essays in Honor of Wayne Brockriede (pp. 43-54). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland.