ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Giving Reasons In Intricate Cases: An Empirical Study In The Sociology Of Argumentation

Introduction

Introduction

No, at the moment there is no such thing as a sociology of argumentation; but it would be nice to have one. The aim of this paper is to show how a sociological approach could possibly enrich our understanding of argumentation.

This is the fourth Amsterdam conference on argumentation, but sociology is still missing from the wide range of disciplines present in argumentation studies. There is a whole branch of sociology, the sociology of knowledge, which should have been interested in argumentation studies from the very beginning – but it was not. Habermas’ landmark work, The Theory of Communicative Action, should have drawn a crowd of sociologists into argumentation theory – but it did not. I think this is an unfortunate situation but one that will change soon. Sociologists are already active in such neighboring fields as discourse analysis, conversation analysis – even rhetorical studies. It is only a matter of time that they discover the importance of argumentation.

We cannot foresee how a future sociology of argumentation will look like, but we can be pretty sure that it will be organized around two main questions: first, how social reality shapes argumentation; and second, how argumentation shapes social reality.

The first question is easier to answer. The unequal distribution of knowledge and skills is a commonplace in sociology. It would be easy to show that the willingness to argue and the skills of arguing as well as the types of arguments actually used are unequally distributed in society and depend on social factors like the gender, the educational level and other social characteristics of the arguers. Standard statistical methods can be used to show the correlation between the social characteristics of the arguers and their arguments.

The second part of this paper will present some exercises of this kind. I will analyze the responses given to an open-ended why-question in a survey on political opinions conducted recently in Hungary. The question first asks whether the 1992 decision of Hungary to abandon the building of the Danube Dam – a huge and environmentally risky barrage system on the border river, a ìjoint investmentî with former Czechoslovakia – was good or bad, and then asks why the respondent thinks so.

This question was recently discussed in the Hague International Court of Justice by experts of international law. The negotiations between the two countries were unfruitful, so they opted for the judgment of this supranational institution. The judgment came out last year and was solomonic. It said that Hungary was not right when it abandoned the project unilaterally, but Czechoslovakia was not right either when it continued it unilaterally.

The mere fact that there is an international court of justice and that the controversy between Hungary and Slovakia had a happy ending, that the end of the conflict was not a bloody war, but a scholarly dispute between polite lawyers, brings us back to the second main question of the sociology of argumentation: how argumentation shapes social reality. I will address this question in the first part of my paper. Taking the decade-long debate on the building of the Danube Dam as a historical example, I will show why the use of arguments (instead of force) was one of the most important stakes of the debate.

1. How argumentation shapes social reality

The Case

In 1977 the Hungarian and the Czechoslovakian government signed an agreement on the joint construction of a river barrage and hydroelectric station on the Danube, between Gabcikovo and Nagymaros, where the river forms the common border of the two countries. The plan was a typical example of those gigantic industrial projects that have been built in the socialist countries since the Stalinist era. There is no need to tell here the whole history of the project. It is a long and sometimes boring history, with lot of dates and names and technical details. However, I have to tell the beginning of the story to show how an economic issue became first an environmental and then a political one. The following narrative is based on an excellent political science article (Galambos, 1992), which summarizes the history of the debate well.

Czechoslovakia started construction already in April 1978, two months before official ratification. The Hungarians were less enthusiastic: shortly after work began on the Hungarian side, public debates over the project began, first in professional associations.

In November 1981, an article harshly criticizing the project was published by a biologist, Janos Vargha, who later became a leading figure of the environmental movement in Hungary. Czechoslovakia resented that the publication of such an article was allowed in Hungary. The nervousness of the Czechoslovakian government was understandable. Two months earlier, the two countries agreed to suspend construction work, because of lack of necessary financing. The Hungarian government unilaterally decided to postpone all work until 1990, and initiated a study on the ecological consequences of the dam system. However, in the several expert committees that were formed, dam engineers managed to assert their point of view.

The Hungarian state and party leaders were more concerned about th Therefore they proposed that Czechoslovakia should build the whole project alone – in exchange Hungary would pay off half of the investment costs with electric energy.

The Hungarian state and party leaders were more concerned about the lack of investment capital than about ecological consequences. Therefore they proposed that Czechoslovakia should build the whole project alone – in exchange Hungary would pay off half of the investment costs with electric energy.

The Hungarians did not manage to “escape” from the project – Czechoslovakia only agreed to take over some of the work. In October 1983 the prime ministers of the two countries signed a modification of the 1977 treaty, according to which the completion of the project was postponed by five years. The Hungarian Politburo had already made a secret decision in favor of project completion in June.

In December of 1983 the Hungarian Academy of Science completed a report, according to which construction should not be continued until an environmental impact assessment is prepared. In the spring of 1984 public debates were held in university clubs and professional associations.

The first grass-root environmental group in Hungary, the Danube Committee, was established in January 1984. The movement collected more than 10,000 signatures in support of a petition, addressed to the Parliament and government, demanding a halt to the construction. The movement grew in size but was not structured. It was therefore sought – unsuccessfully – to found an official association.

But the political leadership toughened its position, prohibiting public discussion and publications against the dam system. Finding itself unable to be registered as an association, the movement founded the unofficial Danube Circle.[i] The Danube Circle broke the ban on public discussion of the dam system by publishing the News of the Danube Circle in samizdat. The bulletin contained documents of debates, information on the historical and political background of the project, and an account of the debate in Austria on the Hainburg hydroelectric plant. In December 1985 the Danube Circle received the Right Livelihood Award (the so-called Alternative Nobel Prize).

Three other movements appeared for a short period: one gathered signatures, demanding a referendum; the Blues demanded that Parliament should discuss the case and decide on it; the Friends of the Danube demanded that at least the construction of the dam at Nagymaros should be stopped. In January 1986, a letter with 2,500 signatures, protesting the project and calling for a referendum, was submitted to the Hungarian Presidential Council (a body which exercised the functions of the head of state.)

Negotiations between Hungary and Austria for a credit agreement were underway. The government would not have been able to continue the construction without finding a solution for the financial problems: it came from Austria, where the construction of the Hainburg water power station had failed to materialize due to the citizens’ protest.[ii]

In January 1986 the Danube Circle, together with Austrian and German environmentalists, held a press conference, protesting against the Austrian financing of the project. The Danube Circle also sent a petition to the Austrian Parliament. In February a “Danube Walk” was organized by the Danube Circle and the Austrian Greens, which was violently disrupted by the Hungarian police. The governmentís action was internationally condemned and the European Parliament passed a protest resolution.

In April prominent Hungarian intellectuals published an advertisement in an Austrian daily, Die Presse, asking the Austrians to protest against their governmentís involvement in the dam system. However, the agreement between Austria and Hungary was signed in May 1986. Austrian banks were to supply loans for the construction of the project, and Austrian companies were to be given 70% of all building contracts; Hungary was to repay the loans by delivering electric energy to Austria, from 1996. Two thirds of Hungary’s share of electricity produced by dam system was to be paid to Austria over a period of 20 years, mainly during the winter months, when the level and the flow of the Danube are at its lowest, therefore the dam system alone could not have provided the required amount of electricity, and new Hungarian power stations would have had to be built in order to amortize the energy debt. The Austrian companies began construction at Nagymaros in August 1988.

I stop the story at this point. Now we are in 1998. Ten years after the construction began at Nagymaros, and half a year after the decision of the Hague International Court of Justice, the debate still goes on. This year, the liberal-socialist coalition has lost the elections – partly because some leaders of the Socialist Party and some bosses of the water-management bureaucracy had the bad idea that it was time to return to the project and realize it. It is not without symbolic significance that one of the first moves of the new government was to nominate Janos Vargha as chief adviser in environmental issues.

Before analyzing the debate, we should have a look at the arguments themselves.

The Arguments[iii]

The Arguments[iii]

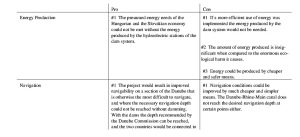

With the exception of the argument of waste, all other arguments are strictly professional. It is difficult to asses their respective strength, but some of the counter-arguments are definitely stronger than the corresponding pro-arguments and in general the counter- argumentation as a whole seems to be stronger. This is probably so because the opponents can propose cheaper and safer alternatives while the supporters must defend an obviously costly and risky project. An other advantage of the opponents is the possibility to use irony and paradox: for instance in showing that the benefits are actually harmful, that the proposed good thing is actually a bad thing.

As expected, and as it is indicated by the number of arguments, the two critical points are the environmental risks and the financial losses. We find here the weakest pro-arguments and the strongest counter-arguments.[iv] The weakest point of the supporter side is the financial one. It is significant that besides the argument of  waste, they do not have any financial argument to defend the project. In fact, they can not have any: profitability was out of question from the beginning.

waste, they do not have any financial argument to defend the project. In fact, they can not have any: profitability was out of question from the beginning.

However, in spite of these weaknesses on the supporter side, the two sides were in equilibrium. The arguments on the opponent were somewhat stronger, but this was balanced by the power position of the other side: the dam builders had all the support of the State and the Party.

A Note on the Argument of Waste

It is interesting to note that the argument of waste has two forms: it can be used as a pro-argument and as a counter-argument as well. As a pro-argument, it says that if you have already invested in a project, you have to continue, because abandoning it means losing money and losing money is bad. But, with a little modification, by adding the choice between more and less, the same argument can be used as a counter-argument. If losing money is bad, then losing less is better than losing more. So, if we must choose between losing less and losing more, we have to choose losing less. Note that the use of the modified form presupposes that in any case, there will be no returns, only losses.

Actually, when the Hungarian government had to decide about the eventual abandonment of the project, an independent expert committee made a cost-benefit analysis. They found that both continuing the project and abandoning it will cause economic losses, but the highest losses would be caused by delaying the decision. On the short run it is more advantageous to abandon the project, on the long run there is no significant difference between its continuation and halting.

If this analysis was correct, the use of both forms of the argument of waste was right, although, again, the counter-argument seems slightly better grounded. The moral of this case is that expert opinions are not always better than those of lay people. In this case, scientific expertise could not really help the politicians, who, not surprisingly, opted for the worst alternative, that of delaying the decision. That was certainly wrong from a financial point of view, but politics has its own priorities. Hungary did not abandon the project until 1992.

Weapons and Reasons

Saying that argumentation shapes social reality may mean many things. It is clear for instance, that public debates can have great influence, but this is trivial. In this trivial sense the debate on the Dam shaped social reality because a little group of concerned scientists, ecologically minded people and political dissidents succeeded to build a strong opposition movement and to activate the public opinion against the project.

What is perhaps more interesting from a sociological point of view is the interplay between the use of power and the use of arguments in society.

In our case it is clear for instance, that the possibility of resolving a major conflict between states with arguments, that is without weapons, was not always granted in history. International law is a relatively recent invention (a Dutch invention, by the way), the Court of Hague is only ninety years old and its real working only started after WW2. Nevertheless, it seems to be a general characteristic of modern societies that they tend to resolve all kind of conflicts in a peaceful way, that is by negotiations. We have got diplomacy and international law to prevent war, parliamentary debates to prevent revolution and civil war, collective bargaining to prevent industrial conflicts, and family therapy to prevent indoor killing, that is, domestic violence. The substitution of weapons with reasons can be viewed as part of this general tendency of rationalization already familiar from Max Weber. The success of these nonviolent solutions, and the fact that they are a lot cheaper than the violent versions, has surely contributed to their diffusion.

However, in spite of this general tendency of rationalization, our society is still very violent. The use of arguments is still an exception, the use of weapons being the rule. Considering argumentation from this point of view, it seems that the most interesting things happen not inside the argumentative framework, but rather on the unsure frontier between the peaceful oasis of argumentation and the large outside world of violence. The most interesting moves, at least from a sociological point of view, are those the aim of which is to force the opponent into the oasis, that is, to transform the bloody war into a rational discussion – where, in principle at least, only the force of arguments counts. This is always difficult, because the opponent has other choices, for instance he/she can use his/her weapons instead.

Now this is America: everybody has weapons, but some people have more powerful weapons than others. We live in a social world where power is unevenly distributed. In this hierarchy of power positions, each of us, even those on the top of the top, can find him/herself in an underdog position if his/her opponent has more power than he/she has. And this is our luck, because as an underdog, we are more interested in rational discussion than in war-making. So we propose cease-fire and rational discussion. The problem is that our opponent, being more powerful than we are, has the opposite interest: he/she is more interested in war-making than in rational discussion. What can we do in this situation? We have three choices:

1. We can try to persuade him/her that rational discussion is a much better solution. This is pure argumentation. It works in the textbooks, but rarely in real life.

2. We can try to force him/her into a rational discussion by using non-argumentative means: this is not argumentation, but it works. The only problem is that, as Habermas says, a constrained consensus does not count as consensus.

3. We can use a mixture of argument and force to drive him/her into a rational discussion. I call this dirty argumentation. It has the best results.

Anyway, in the first and third cases, we use arguments – exclusively or in a combination with other, non-argumentative means – to persuade. This means that arguments are used not only inside but outside the oasis as well.

In fact, we have three concentric circles. Forget the oasis; imagine instead a hotel where the mafia bosses have their annual meeting. They are sitting in a big conference room, where weapons are not allowed. Here argument rules. Anyone who wants to enter the room, has to leave his weapons in the lobby. Outside, in the street, there is war. There are no arguments here, only weapons against weapons. And between the two, the lobby. Here we find weapons and arguments as well: armed gorillas try to persuade mafia bosses to leave their weapons outside. They use arguments to persuade them, but they can use their weapons, if necessary.

In fact, reality is a little bit more complex, because sometimes there are shootings in the conference room and rational discussions take place in the street; but these are exceptions and we do not have to deal with them here. What is important for us is that we are all members of the mafia and spend most of our life in the street and in the lobby. Occasionally, we enter the conference room and spend there some time, but not very often.

Now Argumentation Theory, as far as I can see, spends most of its time in the conference room. This is OK, since most pure argumentation occurs there. There is nothing wrong with this choice: if you want to study pure argumentation, this is the right place for you. Even if some interesting dirty argumentation occurs in the lobby, Argumentation Theory has all the right to say: there is nothing wrong with me; it is true that I am sitting in the conference room, but I can see very well from here what happens in the lobby.

Well, maybe it can. But my point is just this: Argumentation Theory observes the whole world from the conference room. That is, the whole world of argumentation from the point of view of pure argumentation. I am afraid this is not the best perspective, since in real life, most argumentation belongs to the dirty type. I accept that pure argumentation is an important subject and even that dirty argumentation can be studied – maybe with some extra work – from the perspective of pure argumentation. The problem is that things look different from this conference room perspective; I mean different from what they really are.

I take the example of pragma-dialectics, the version of Argumentation Theory I know the best, and I like the best. In pragma-dialectics the world of argumentation looks as if scientific discussion was the dominant type of argumentation. For this clean world of pure argumentation to exist, the whole problem of violence and power must be eliminated at the very beginning. And in fact, it is. The only place where this world of violence is mentioned at all is in the first rule of the “Ten Commandments” where it is treated as the ad baculum fallacy (van Eemeren and Grootendorst, 1992: 107-110).

Of course, if the use of force makes any kind of rational discussion impossible, the appeal to force is a fallacy of the worst kind and must be treated as one. However, eliminating it analytically will not resolve the problem. The problem is that the possibility of using force instead of arguments is always present in real life situations and its presence influences argumentation to a great extent. Even in a real conference room, the persuasive force of an argument depends not only on its inherent quality, but also on the real life power of the arguer. Everybody is aware that life continues after the end of the discussion and arguments are evaluated in the light of this knowledge. Arguments tend to be perceived as strong if they are advanced by someone who has power and weak if they are advanced by someone who has not.

Social life is a power game and argumentation is only a remarkably nonviolent variety of it.[v] Sometimes we opt for the nonviolent variety and it can be very consequential what happens in these short argumentative interludes. This is why the study of pure argumentation is so important.

However, these episodes of pure argumentation are always embedded in and preceded by vast bodies of dirty argumentation. Perhaps we should pay more attention to dirty argumentation and to these rare but critical moments when the rules of the game suddenly and unexpectedly become more powerful then the most powerful of the players; when those who are armed put aside, for some reason, their arms and accept to fight with naked hands; when the players, even those who could do otherwise, really give a chance to the best argument to win. They may have many reasons to do this: to save their face, their dignity, to show their talents, their ability, to gain popularity – or simply because they are too stupid to recognize the danger. Anyway, these are great moments, because they let us pass in a different world where we are all equals, there is no violence and the best argument wins.

After this short theoretical introduction, we will see in a different light what happened in the debate about the Dam.

Dirty Moves: Case Analysis

Perhaps the most important observation we can make is that the conference room situation is characteristically absent from the public debate. It appears only outside the debate, as the working of the Hague International Court of Justice for example, or in its pores, as the expert discussions in the committees of the Academy of Sciences. But the debate as a whole was not a rational discussion. It was about the need and the possibility of a rational discussion, but it was a lobby debate. The protest movement people tried to persuade the public and the decision-makers that there is a risk situation and that is good reason enough to begin a rational discussion about the project. On the other side, the decision-makers tried to persuade the public that there is no risk and persuade the protest people that, even in a soft dictatorship, they have much to lose.

The most important consequence of the first few moves of the protest group was the politicization of the debate, something what probably was not intended by the group. At the beginning, the group was composed of concerned scientists and a few green activists, but members of the democratic opposition were absent yet.

The group desperately needed freedom of press and freedom of expression as means to realize its main goal, the activation of the general public. Now freedom of press and freedom in general were the main goals of the democratic opposition, so environmentalists and dissidents discovered that they share some important common goals. This made the partial fusion of the two movements possible.

One of the consequences of this fusion was the activation of quite large fractions of the civil society. People who sympathized with the democratic opposition but did not manifest these sympathies because they were afraid to lose their job or to be harassed by the police, now recognized the opportunity and became followers of the movement. They exploited the opportunity that now they could be proud members of the opposition without taking too much risk. After all, protection of the environment is a non-political issue, and every concerned citizen has the right to express his anxiety if the environment is in danger. Both the environmentalist and the political dissident wings of the movement were happy with this reaction because the growth of the movement was their common interest.

However, the Politburo and the government were not so stupid to believe that this suddenly discovered concern for the environment was without political motives. They perceived the growth of the movement as a politically dangerous development and wanted to react accordingly. Nevertheless, their situation was delicate. On the one hand, the movement was politically dangerous, but it seemed even more dangerous to ban every manifestation. After all, it was not an outright political movement. Persecuting it would mean to recognize it as an authentic political opposition movement, and to declare war. Now the government was not interested in making war because the image of the late Kadar era was that of a tolerant, laissez-faire reform regime. On the other hand, the government realized that the movement could be used as an argument, together with the reports of the expert committees, in its discussions with Czechoslovakia. The government was not concerned by the ecological risks of the Dam, but it was concerned by an eventual financial crisis, and wanted to abandon this costly project. Nevertheless, it desperately needed good arguments, so it made some concessions to the opposition in order to gain popularity and be able to use the ecological argument in its discussions with Czechoslovakia. It was in this complex situation that the opposition succeeded to force the government to enter into a dialogue with the movement and with the civil society.

Both sides used dirty argumentation in this dialogue, because it was a real life, public debate with great risks, so they could not permit the luxury of a fair and rational discussion. Arguments and force were equally used, and most of the arguments were fallacious.

There is no need here to discuss the use of force. It is evident that both sides used non-argumentative means, the most spectacular examples being the violent dissolution of the ìDanube Walkî by the police and the prohibition of public discussions and publications against the Dam. There is a difference, though: the protest movement has never used violence. The non-argumentative means used by them consisted almost exclusively of the force of public sphere: collecting signatures in support of a petition, founding an unofficial pressure group (the Danube Circle), or publishing samizdat literature, etc., they used and at the same time created their only “weapon”: the activation of the general public. Ironically, however, their use of non-argumentative means threatened the government more, than the use of violence by the government threatened them.

Now let us see the basic argumentation of the two parties. Although ad hominem and ad baculum arguments were abundantly and routinely used, I will focus here on the appeal to expertise.

At the beginning, the protest movement is powerless, so their main strategy is to challenge the government. The implicit but unmistakable challenge behind their actions reads something like this: “Let us talk about your project! If it is really good, you do not have to be afraid of discussing it.”

At first sight, it seems that the government must face a dilemma. If it does not accept the challenge, this is a proof that the project is not good enough; but accepting it may also suggest that the project is not good enough, and, in addition, proves the weakness of the government. Moreover, accepting the challenge and entering into a discussion may lead to a disastrous defeat.

However, the government does not have to face the dilemma: it has other choices as well. One of its possible responses is this: “The project is good, and we are not afraid of discussing it. But this is experts’ business and you are not experts. So we will not discuss it with you.” This is the classical form of evading a challenge without losing face. It is very common, even young children use it: “You are not strong enough to fight with me.” Basically, this is an appeal to equality and fairness: only equals can have a fair fight; we are not equals; so we will not fight. If the challenged uses it well, he/she can save his/her own dignity without insulting the other, but it can be used as an insult or as a face saving device as well.

The appeal to expertise is frequently used in public debates. It has formally the same structure as the appeal to equality and fairness, but it is applied usually as a face saving device. Ironically enough, the appeal to equality is used here to make the transition into a rational discussion impossible. The invitation of the weaker party to fight with naked hands, that is, with arguments, so that both parties have equal chances to win, is rejected by the stronger on the ground that the weaker party lacks the necessary expertise.

The appeal to expertise used by the government was really a combination of an ad hominem and an appeal to authority: This combination of the two arguments seems to be strong, but it has five premises, which gives five points of attack to the opponents.

In fact, the protest movement attacked all five premises. First, by recruiting a large number of scientists from a great variety of specialties, they succesfully refuted (5). Second, by introducing the environmental issue, they refuted (1) and (4) on the ground that the protection of the environment is everybody’s business. Finally, by pointing out the contradictions and the divergences between various expert opinions, they discredited (2) and (3).

As the image of the protest movement changed, the government also changed its strategy. For example, when the expertise of the opponents could not be denied any more, the government used a slightly modified version of the appeal to expertise: “Yes, you are experts, but this is a political (a foreign relations) affair and you do not know about politics (foreign relations).” When the movement found an ally in the democratic opposition, the government used a circumstancial ad hominem: “Yes, you are experts, but you have a political interest in the matter.”

Unfortunately, there is no room here to give a more detailed analysis. I hope that I said enough to show the general direction of my argument and to justify my critical position concerning the perspective of Argumentation Theory.

2. How social reality shapes argumentation

The Data

The data I am going to analyze here are from a representative survey made in Hungary, in December 1997. It was conducted by Róbert Angelusz (ELTE University of Budapest, Institute of Sociology) and Róbert Tardos (Academy of Sciences, Communication Theory Research Team).[vi] The sample consisted of thousand persons. The questionnaire consisted of ten parts. Parts G, H and I were about political opinions. Part G asked questions about foreign relations, for example about Hungary’s plans to join the NATO and the EC. At the end of this panel there was a question about the decision of the Hague International Court, and another one about Hungaryís decision to abandon the building of the Dam in 1992.

This second question was open-ended and formulated in these words: What is your opinion about Hungary’s 1992 decision to denounce the treaty with Slovakia; was it right? If the person answered yes or no, he/she was asked to argue in defense of his/her standpoint: Why do you think so?

Among the 995 people who answered the questionnaire, a rather high percentage, 38.5 % did not answer this question or answered by “I do not know.” The rest, 61.5 % answered by yes or no and most of them advanced at least one reason to defend their standpoint. As this was an open-ended question, they were allowed to advance several arguments, but only a minority of them advanced more than one.[vii] The distribution was the following:

14.1 % said only yes or no, but had no arguments;

39.6 % advanced one argument, and

7.8 % advanced two arguments.

The Arguments

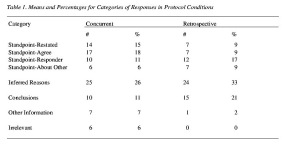

During the coding process, the researchers found no less than 17 different types of argument. Here I present only the five most frequently mentioned pro-arguments and the five most frequently mentioned counter-arguments.

The pro-arguments:[viii]

14.8 % said yes, it was a good decision because of ecological reasons;

7.0 % said yes, because it was a bad treaty anyway;

2.6 % said yes, because the project was a waste of money;

1.2 % said yes, because there was no way to negotiate with the Slovaks;

0.6 % said yes, because that was what the opposition was fighting for; and finally 1.8 % advanced other reasons.

On the other side,

10.9 % said no, it was a bad decision because it would have been better to finish the project;

6.8 % said no, because we already invested a lot of money in the project;

3.0 % said no, because we need the electric energy the Dam will produce;

1.7 % advanced the argument of pacta sunt servanda, that is, if you have a contract, you have to observe it;

1.1 % said no, because the Hague decision found that Hungary had no right to abandon the project unilaterally; and finally

2.1 % advanced other arguments.[ix]

The second and third pro-arguments and the first and second counter-arguments are different versions of the argument of waste. (Although the bad treaty and the better to finish arguments can be interpreted as cases of petitio principii as well.) Here too, it is used in both senses: as a pro-argument and as a counter-argument as well.

There are two political arguments on the side of the opponents. We may feel the taste of some ethnic prejudice in one of them, but I think there is no prejudice here: in fact there was no way to find a solution with the Slovak party.[x] The other political argument introduces the role of the opposition: this one is something between a petitio principii and an appeal to authority. (It was good because it was good and it was good because an authority said so.)

It is interesting that on the supporter side there are no less than four arguments appealing to the law. There is only one making explicit reference to the Hague decision, (an appeal to authority and/or to law) but there is the pacta sunt servanda argument and there are two others between the less frequently mentioned arguments that have roughly the same character: one says that it is not good to go to court, the other says that it is better to negotiate. These are what rhetoricians call sententia. The pacta sunt servanda argument makes appeal to an age-old legal principle, the two others are proverb-like principles of common sense, but all three are used here as appeals to common sense.

Finally, we can find here the two most important arguments used by the experts: the appeal to ecological damages on the opponent side and the appeal to energy needs on the supporter side. Strictly speaking, only these two are issue-dependent arguments. If we compare this pattern with that of the expert debate, where only the argument of waste was more or less issue-independent, we can venture the conclusion that lay people are more likely to use issue-independent arguments.

1. This is experts’ business.

2. What experts say in experts’ business is true.

3. Experts say that the project is good.

4. Only experts can have a say in experts’ business.

5. You are not an expert. Therefore it is good. Therefore you cannot have a say in this business.

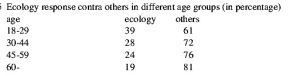

One more word about the relationship between social characteristics and argument types. Regression analysis has shown that the use of the most frequently mentioned ecological argument is determined by the age of the respondents: young people (under 30) are two times more likely to use the ecological argument than senior citizens (over 60).[xi] However, there is a difference here between men and women: in the case of women, there is no significant relationship between young age and the use of the ecological argument.

Argumentative Skills and the Willingness to Argue

Theoretically, we may suppose that the ability to choose a standpoint and to advance arguments in defense of it depends on certain learned skills, on something we may call argumentative competence. Those who perform well, that is those who have fewer difficulties to choose a standpoint and to advance arguments when they are explicitly asked to do so, can be considered more skilled, more competent. But it is not sure at all that this is really so. We know from sociolinguistical studies – especially important are here the studies of William Labov – that the situation influences enormously the performance of the speakers. (Labov 1972) As a result, there is very little ground to say anything sure on the competence of the speakers on the basis of their performance.

People from lower social strata (or – and this is quite the same – with lower educational level) especially tend to employ risk-evading strategies in situations they feel menacing – for instance in exam situations. Now a survey interview situation is much like an exam situation, at least for some people – again, especially for people from lower social strata. If they feel that a question is “too difficult”, that answering it demands some political knowledge, they are more likely not to answer it at all or to take only minimal risks. The question about the Dam was definitely of this kind, so it is not surprising that the rate of non-answering was high. Those people did not take any risk at all. The same can be said about differences in presenting arguments. Those who opted for minimal risk-taking, advanced a standpoint, but were not willing to advance arguments in defense of it.

That is why I use the expression “the willingness to argue” instead of “argumentative skills.” Argumentative skills can be very good even if the given performance is poor. At other times, at other places, the performance of the same people can be surprisingly good. People who did not answer this question or did only with minimal risk-taking, are perhaps very talkative on the same issue in a pub or between friends. In general, it can be said that survey data give very little ground to evaluate argumentative skills. If we really want to know about skills, direct observation is a much better method.

On the other side, it can be said that people have to use their skills in real, sometimes menacing social situations, so the question of competence is not really important, because in real life, only the performance counts. So survey data are perhaps more informative on real life, then data from direct observation or from laboratory experiments.[xii]

This is only to say that, after all, survey data can be interesting. The only thing I want to show here is that argumentative skills – measured by the willingness to argue – are unevenly distributed in society. I use a very simple indicator for measuring the willingness to argue: I suppose that providing two arguments is better than providing one, one is better than none, and opting for a standpoint is better than saying nothing.

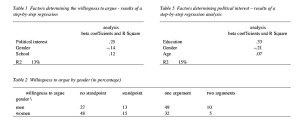

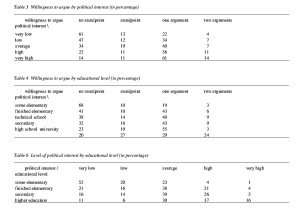

Regression analysis has shown that the willingness to argue depends on three factors: the respondentís gender, educational level and degree of political interest.

Here are some simple tables. They show how the independent variables influence the argumentative performance of the respondents. While the non-response rate of men is less than 30 %, half of the women had no answer to this question. Sixty per cent of the men present one or two arguments, while only 37 % of the women do this. This is not surprising. As Bourdieu says in his famous article “L’opinion publique n’existe pas” (Bourdieu, 1973), if we want to know which questions have political coloring, we only have to examine the response rates of men and women: the bigger the difference between the response rates, the more political a question is.

I have to note that there is no significant difference between men and women at the lowest and highest educational level, which probably means that men with unfinished elementary school behave more like women, that is they are timid, while women with university level behave more like men, that is they feel strong enough to argue, even about politics.

As this is a political question, there is a significant relationship between the level of political interest and the willingness to argue. If the level of political interest is very low, only one quart of the respondents present arguments, if it is moderate, half of them, and if it is very high, three quarts of them presents arguments.

Next comes the influence of schooling (table 4). This is a very clear picture. The big gaps are between “some elementary” and the others and between “university” and the others. Almost seventy percent of those who have not finished elementary school, have no standpoint.

At the other end of the hierarchy, we can note the extremely high percentage of university level respondents who advanced a second argument. There is no need to say that political interest itself is a dependent variable. Regression analysis has shown that it depends on three factors: gender, educational level and age.

Men and educated people are significantly more interested in politics, than women and less educated people. While the percentage of men interested or very interested in politics is 36.2, the same value for women is only 20.5. The following table shows that education has an even stronger influence on the level of political interest: the percentage of people with higher education interested or very interested in politics is 53, while the same value for people with unfinished elementary school is only 5.

Here too, the big gaps are between ìsome elementaryî and the others and between “higher education” and the others.

To summarize: according to our data, argumentative performance – measured here by the willingness to argue – depends on the respondents’ level of political interest, educational level and gender. As political interest itself depends on the respondents’ educational level and gender (the effect of age being negligible), and as gender itself is the product of education (or socialization), the single most important factor determining argumentative performance is education (or socialization).

A Lesson from Simmel

A received view in rhetorical studies is that the ability to use rhetorical devices is evenly distributed among the members of a society. A scholar of rhetoric says  somewhere that the language of the fish market is as rich in tropes and other rhetorical devices as the language of the most educated class.

somewhere that the language of the fish market is as rich in tropes and other rhetorical devices as the language of the most educated class.

If this is true, and if rhetoric has something to do with argumentation (and we know it has), we should infer that argumentative skills too, are evenly distributed among the members of a society. Unfortunately, this is not so. Sociology can show us that these skills, like most other goods and privileges, are unevenly distributed.

This has clearly to do something with power relationships. Women are more timid than men not by nature: they are socialized this way. Men have more power and so they have more self-confidence, more self-esteem. This is why they are more likely to answer questions, to choose a standpoint, to advance arguments. The same is true for people with higher educational levels or with higher social status.

There is an interesting contradiction here. On the one hand, argumentation presupposes the equality of participants, the neglect of power differentials, the suspension of the use of power and violence. On the other hand, it is clear that the social context is always a power context and that even the ability of arguing is determined by the place of the individual or the group in the hierarchy of power relations.

In his famous study on ‘Sociability’, Simmel analyzes a somewhat analogous situation. A social gathering, just as a rational discussion, presupposes the equality of the participants. Socializing, just like the resolution of differences by using persuasive arguments, has an essentially democratic character. In both cases, one has to leave his/her social status outside to be able to play the game and let the others play. This is a difficult thing to do, and even in the case of socializing, it cannot be done but within certain limits. Here is what Simmel says:

Sociability emerges as a very peculiar sociological structure. The fact is that whatever the participants in the gathering may possess in terms of objective attributes – attributes that are centered outside the particular gathering in question – must not enter it. Wealth, social position, erudition, fame, exceptional capabilities and merits, may not play any part in sociability. (…)

[The principle of sociability] shows the democratic structure of all sociability. Yet, this democratic character can be realized only within a given social stratum: sociability among members of very different social strata often is inconsistent and painful. (…) Yet the democracy of sociability even among social equals is only something played. (…)

Yet, this world of sociability – the only world in which a democracy of the equally privileged is possible without frictions – is an artificial world. (…) Sociability is a game in which one ‘does as if’ all were equal… (Simmel, 1950:45-49) (All emphases from Simmel.)

What Simmel says here about “sociability” is highly relevant for us. One can even replace the word “sociability” with “rational discussion” and reread the citation above. It makes perfectly sense, because a rational discussion must meet the same requirements of equality. Just like socializing, a rational discussion is “a social work of art”, a game in which one does as if all were equal, an artificial world in which the strong makes himself the equal of the weaker.

But the analogy is not perfect. Even sociability, says Simmel, can only be realized within a given social stratum, because to play the game, people must take no notice of the different social status of the participants, which can be difficult if members of very different social strata are present. However, with some extra work, it can be done. Although equality is faked, and each of the participants knows this, they still may want to play the game, because it is rewarding.

In the case of a rational discussion, the name of the game is the same – “we are all equals now” –, but one should be able to leave outside not only his/her social status, but his/her socialized self as well; and this cannot be done. People entering in a rational discussion cannot change themselves for this occasion: they were socialized in a particular way, according to their position in the power hierarchy, and now they act according to their different habitus. It is not surprising then that their argumentative skills are unequal and, consequently, they have unequal chances to participate in the discussion and to advance good arguments. Their current performance in the discussion is limited by their competence, which was forged before and outside the equality conditions of the discussion.

Conclusion

In argumentation studies, it is a common presumption that arguments have some inner persuasive force. Some arguments are strong, some others are weak. Moreover, there are bad and good arguments. Fallacies, for example, are bad arguments. We assume that in a rational discussion, bad arguments are eliminated and the best argument has to win.

This is certainly so in an ideal speech-situation, and I think Habermas is not wrong when he says that even in normal conditions, when the situation is far from the ideal, these expectations work and regulate somehow our behavior. We know how it should be done, even if it cannot be done that way.

This is a great insight, but it does not change the fact that in real life debates, the inner force of arguments is rarely as important as the power position of the arguers. This does not mean that arguments do not have some inherent force; they do, but in real life situations they have this extra force as well. The inner force of arguments can make a difference, but only if certain very special conditions are met.

These conditions are, of course, social conditions. In some cases it is so important to make a distinction between bad and good arguments, that there are a few strictly regulated forms of communication specifically designed for pure argumentation. A few important social activities, like law or sciences, are expressly organized around the requirements of pure argumentation. From time to time, pure argumentation occurs even in everyday life, but only as an exception. Otherwise, we use power, and, at the very best, dirty argumentation.

When, in a discourse on ‘Argumentation and Democracy’, van Eemeren introduces certain “higher order conditions” as preconditions of a rational discussion (the respect of the rules of conduct prescribed in the pragma-dialectical model being a “first order” condition), he implicitly acknowledges that the inner force of arguments makes a difference only if certain very special conditions are met. According to his distinction, “second order” conditions are the “psychological conditions” of the arguers, among them “their ability to reason validly”. “Third order” conditions are the social conditions of the discussion, among them the “socio-political” equality of the arguers. Here is the relevant section of his text:

We can think of the assumed attitudes and intentions of the arguers as ‘second order’ conditions that are preconditions to the ‘first order’ rules of the code of conduct. The ‘second order’ conditions correspond, roughly, to the psychological make-up of the arguer and they are constraints on the way the discourse is conducted. Second order conditions concern the internal states of arguers: their motivations to engage in rational discussion and their dispositional characteristics as to their ability to engage in rational discussion.

Second order conditions require that participants be able to reason validly, to take into account multiple lines of argument, to integrate coordinate sets of arguments, and to balance competing directions of argumentation. The dialectical model assumes skills and competence in the subject matter under discussion and on the issues raised. (…)

But not only must participants be willing and able to enter in a certain attitude, they must be enabled to claim the rights and responsibilities associated with the argumentative roles defined by the dialectical model. To say that in dialectical discourse everyone should have the right to advance his view to the best of his ability is to presuppose a surrounding socio-political context of equality. This means that there are conditions of a still higher order to be fulfilled than second order conditions: ‘third order’ conditions. Third order conditions involve ideals such as non-violence, freedom of speech, and intellectual pluralism. The dialectical model assumes the absence of practical constraints on matters of presumption in standpoints. The goal of resolution of differences ‘on the merits’ is incompatible with situations in which one standpoint or another may enjoy a privileged position by virtue of representing the status quo or being associated with a particular person or group…. [T]he conditions I am referring to are also among the necessary conditions for the operation of the democratic method… (van Eemeren, 1996:13)

Van Eemeren admits that the dialectical approach is “a little bit” – “but not too much” – “Utopian”, but he hopes that with more and better education the idealistic requirements of the pragma-dialectical model can be met (van Eemeren, 1996:14).

It must be clear for now that the author of this paper entertains doubts as to the validity of the above assumptions and the well-foundedness of this hope. We have to realize that these assumptions are really theoretical postulates: they have very little to do with the reality of social life. For it is simply not true that people are equally motivated and able to engage in rational discussion; that they are equally able to reason validly, to take into account multiple lines of argument, and so on; that they all have the assumed skills and competence; that they always have the right to advance their view to the best of their ability – and so on.

What Argumentation Theory presupposes – equality – Sociology has to deny. Society – and there is countless empirical evidence for this – is a system of inequalities. The real question, for Sociology, is the following: How in this system of inequalities argumentation is possible at all? As I see it, this question can only be answered from a power perspective. Interestingly enough, what makes dirty argumentation possible or frequent is the same thing what makes pure argumentation impossible or, at least, rare and limited, namely, the unequal distribution of power in society.

The Sociology of Argumentation has to begin its work where Argumentation Theory abandons it: at the frontier of pure and dirty argumentations. In this way, with the cooperation of Argumentation Theory and the Sociology of Argumentation, a coherent and tenable theory of argumentation can be built, based on more realistic assumptions.

For this future Sociology of Argumentation, I propose the following theses to consider:

1. The ability to reason validly is in a great measure socially determined. Social inequalities (reproduced first by primary socialization, then by the educational system) make the distribution of reasoning abilities uneven, which

2. makes the equality of the participants of most discussions illusory, and, as a result,

3. makes the problem solving capacity of most discussions limited.

4. However, the same social inequalities – especially the uneven distribution of power in society – make the use of arguments (instead of power) necessary and desirable for the powerless (that is, for each of us), while, on the other hand,

5. the uneven distribution of power in society makes the practice of resolving disputes by means of pure argumentation socially limited.

NOTES

[i] It only became a registered organization in 1988.

[ii] The Austrian companies were looking for new opportunities after the construction of the Hainburg hydroelectric plant had been stopped by popular protest in 1984. The well-established Austrian dam-building industry, facing a decreasing selection of new sites and growing public opposition at home, became a major dam-builder abroad, especially in the Third World and in Eastern Europe. Several controversial hydropower projects have been built with the contribution of Austrian money and technology all over the world. Dam-builders had to face fewer obstacles in countries where public protest was illegal, decision-making was done in secrecy, and economic and ecological considerations were overrun by political ones.

[iii] This presentation of arguments is also based on (Galambos, 1992).

[iv] To evaluate the strength of ecological counter-argument #1, one have to know that the underground fresh water reserve in question is the largest in Europe, and that the expected climatic changes caused by the greenhouse effect make water a strategic asset.

[v] In a way, and paraphrasing Clausewitz, argumentation is nothing but the continuation of war with other means. This is why we talk about arguments in terms of war. “We can actually win or lose arguments. We see the person we are arguing with as an opponent. We attack his positions and we defend our own. We gain and lose ground. We plan and use strategies. If we find a position indefensible, we can abandon it and take a new line of attack. Many of the things we do in arguing are partially structured by the concept of war.” (Lakoff, 1980 : 4) On the other hand, and this is one of the main points of this paper, argumentation is just the cessation of war.

[vi] I would like to thank Robert Angelusz and Maria Szekelyi for their invaluable help in writing this part of the paper.

[vii] Maybe some of them advanced more than two, but only the first and second arguments were coded.

[viii] Here, the pro-arguments are those in favor of the decision, that is those of the opponents of the project.

[ix] Namely, that it is not good go to court; that it is better to negotiate; that it would be better for the environment to continue the project; that we lost the Danube; that we lost workplaces; and so on.

[x] The argument was used by a few people with some elementary education. I have no room here to argue in defense of my opinion that there is no prejudice here, but I have some, well, rather weak, arguments.

[xi] Ecology response contra others in different age groups (in percentage):

[xii] This is a difficult question, because we have to deal here with two kinds of ‘reality’. Both are social, but in a way different. One can say that we have to observe argumentation in a pub, because the real argumentative competence of people appears only there. In a sense, this is true, but this is a different kind of reality. No doubt, this is real life, too, but has very little to do with this other ‘real life’ outside the pub, where we have exams sometimes. Let me use an analogy: a survey on party preferences may say very little about ‘real preferences,’ because some people do not want to talk about their preferences. But the survey can give a pretty good prognosis on the results of the next elections, because most of these people will be absent, and most of the other people will vote for the party they preferred. And what is more real then the results of an election?

[xii] This is a difficult question, because we have to deal here with two kinds of ‘reality’. Both are social, but in a way different. One can say that we have to observe argumentation in a pub, because the real argumentative competence of people appears only there. In a sense, this is true, but this is a different kind of reality. No doubt, this is real life, too, but has very little to do with this other ‘real life’ outside the pub, where we have exams sometimes. Let me use an analogy: a survey on party preferences may say very little about ‘real preferences,’ because some people do not want to talk about their preferences. But the survey can give a pretty good prognosis on the results of the next elections, because most of these people will be absent, and most of the other people will vote for the party they preferred. And what is more real then the results of an election?

REFERENCES

Bourdieu P. (1973) L’Opinion publique n’existe pas. Les Temps Modernes, Janvier 1973. 1292-1309.

van Eemeren F.H. and Grootendorst R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication and Fallacies. A Pragma-Dialectical Perspective (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, Hove and London).

van Eemeren F.H. (1996). Argumentation and Democracy. Speech Communication and Argumentation 2, 4-19.

Galambos J. (1992). Political Aspects of an Environmental Conflict: The Case of the Gabcicovo-Nagymaros Dam System. In:

Perspectives on Environmental Conflict and International Relations. Kaukúnen J., ed. (Pinter Publishers, London and New

York).

Labov W. (1972). The Logic of Nonstandard English. In Language and Social Context. Giglioli P.P., ed. (Penguin Books, New

York).

Lakoff G.J. and Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphores We Live By. (University of Chicago Press, Chicago).

Simmel G. (1950) The Sociology of Georg Simmel. (The Free Press, Glencoe, Illinois).