ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Arguing Emotions

These reflections on emotions in rhetorical argumentative discourse build on Walton’s pioneer work while re-evaluating the role of emotion in argument. First, I’ll list some important questions which, nevertheless, can’t be dealt with here since they would go beyond my present scope. Second, I’ll present the general framework of the study ; third, I’ll propose a method permitting a systematical treatment of emotion in some kind of discourses, and, by way of conclusion, I’ll give a brief illustration.

These reflections on emotions in rhetorical argumentative discourse build on Walton’s pioneer work while re-evaluating the role of emotion in argument. First, I’ll list some important questions which, nevertheless, can’t be dealt with here since they would go beyond my present scope. Second, I’ll present the general framework of the study ; third, I’ll propose a method permitting a systematical treatment of emotion in some kind of discourses, and, by way of conclusion, I’ll give a brief illustration.

In the discussion, I’ll use the following two examples (these texts are analyzed more fully in Plantin, to appear a, b, c.) :

– A militant text about Ex-Yugoslavia, entitled “Sarajevo : Citizenship Assassinated” [Sarajevo : La citoyenneté assassinée]. This text constructs in an ideal audience, emotions ranging from apathy to pride, via shame. It is a classical written rhetorical address, delivered by a leader of a democratic movement ICE “Citizens Initiative in Europe” [Initiative des Citoyens en Europe], calling for democratic action and intervention in Ex-Yugoslavia. This address, which will be referred to as (D1), introduces a leaflet entitled “Ex-Yugoslavia – Proceedings of the Third ICE Meeting, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Ulm Street, Paris, December 1992” [Ex-Yougoslavie – Compte-rendu de la troisième rencontre ICE, ENS Ulm, Paris, décembre 1992].

– A paper from the newspaper Le Figaro (moderate wing of the right) February 13, 1997, about the evolution of the structure of the French population since the beginning of this century : more and more people live in town, less and less people in the country. As shown by the title “The empty parts of France : the frightening figures” [La France du vide : les chiffres qui font peur], this text exemplifies the rhetorical construction of fear ; it will be referred to as (D2).

1. Preliminary questions

To investigate the emotional involvement of participants in a communicative event would be a whole program, maybe a domain, in itself. It goes without saying that essential problems can’t be touched here, such as :

– The problem of the universality of so-called basic emotions : are they universal or language and culture specific ?

– The connection emotion – action.

– The conceptual / terminological distinction between emotion, affect, feeling, or psychological state. All these terms will be used indifferently in this paper, “emotion” being considered as an “umbrella term”.

– The question of emotion as drawing a dividing line between rhetorical studies and argumentation studies won’t be tackled, either as a conceptual question or as a historical legacy.

– and finally, the problem of the evaluation of “emotional interventions”.[i]

We’ll focus on the discursive / rhetorical dimension of emotion.

2. A basic situation : dissenting about emotions

If we turn now to the general framework, one fundamental point must be made first.[ii] Some situations or events are intrinsically perceived as “emotional”, for example dangerous and fearful (imagine a big truck speeding towards you). In other situations the same information, linguistic or perceptual, doesn’t elicit the same emotional reaction : One person may feel nothing while the other may overreact ; it’s an individual matter, rather like a musical event. Consequently, some psychologists (though not all) argue that there is a cognitive component in emotion. Thinking of the link language-cognition, a rough formulation of our research question would be : are there linguistic counterparts or correlates of this cognitive component ? Such a program can build on a whole set of research in pragmatics, pyschology, discourse analysis and grammar. The following ones are particularly interesting : Cosnier (1994) ; Scherer (1984a, 1984b) ; Caffi & Janney (1994) ; Ungerer ; Balibar-Mrabti (1995). Classical rhetoric should appear right on the top of this list (Lausberg, 1960) : actually, it is very often possible to trace back some modern “principle of inferencing” or “emotional axis”, or “cognitive facet” to some well-known old rhetorical topos or rhetorical recipe. So, to use Scherer’s words, I would say that I’m interested in the structure of the linguistic component of emotions. Now, this is a very general theme, how is it related to argumentation studies ?

Argument will be considered as basically a discursive activity, developping in specific languages and cultures[iii]. Argumentative interactions and addresses are very good objects to start with when one studies emotion in discourse, for two reasons. First because in argumentative discourse, people are deeply involved in what they say, maybe even more than in any other form of discourse. There is a striking discrepancy between the rich emotional texture of argumentative discourse – and the poverty, the lack of systematicity of the tools at our disposal to deal with this texture.

The second reason is that argument supposes a dissensus ; once again, contradiction makes us see something interesting. Example :

(1)

A : – I’m afraid !

B : – Me too !

B assents to A’s utterance and shares her feelings. The temptation here is to consider that these two people agree just because the situation is frightening in itself : they share the situation, they have the same perceptual system, a causal process took place, producing fear in these two people; so their common fear seems to be perceptually/physically induced by the situation. Now, dissensus reveals that such is not obligatorily the case :

(2)

A : – I’m not afraid

B : – You should be !

Disagreement is linguistically richer than agreement. B’s dissenting utterance opens up on a justificatory sequence : now B has to explain why she disagrees. In other words, B has to argue for her emotion.[iv] Under its most general definition, argumentative discourse is a discourse supporting a thesis, something one should believe ; or a discourse providing reasons for something one should do. In the same way, speakers argue their emotions. They give reasons for what they feel and for what you should feel. They can do so because emotions are not something that fall on people like a book falls on the ground in virtue of a physical law.Because they are linguistic-cultural entities, emotions can be questioned :

(3)

That is not a reason to be in such a state!

Crude facts do not determine emotions. If P is dead, some emotion is certainly in order, but according to one’s ideological system (that is, principles of inferencing), it is possible to argue for joy or for sadness:

(4)

A : – Let’s rejoice, the tyrant is dead !

B : – Let’s mourn the death of the Father of our Country[v]

(5)

X : – Our brand new townhall is the most beautiful, I’m proud of it !

Y : – When I think of the cost, and all the unemployment, I’m ashamed !

To take an example from real political life, the following exchange gives evidence of the importance of discursive emotional display in political discourse[vi] :

(6)

The distress I feel concerning the repeated and tragic actions that you have undertaken as Head of the Israeli Government is real and truly profoun.

La détresse que j’éprouve suite aux actions tragiques et répétées que vous avez prises à la tête du gouvernement d’Israël est réelle et profonde.

First sentence of the letter adressed on March 9, 1997, by King Hussein of Jordan to the Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahou.

I have read your letter with deep anxiety, the last thing I would wish is to provoke your doubt and bitterness

J’ai lu votre lettre avec une profonde inquiétude, je ne voudrais surtout pas susciter le doute et l’amertume chez vous.

First sentence of the answer addressed on March 9, 1997, by the Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahou to King Hussein of Jordania. Quoted from Le Mond, March 15 1997, p. 3 (translation translated).

Maybe one of these political partners doesn’t feel distressed and the other one doesn’t feel anxious. Maybe militants and/or future historians will tell us that these linguistic emotional displays were just emotional lies, serving machiavelic strategies. Discourse analysis, led from a linguistic point of view, gives no access to the reality of the feelings.

The conclusion will be that the discursive dimension of emotions appears with a particular clarity when emotion is in debate, I mean when the object of debate is emotion itself. So, our point of departure will be a/ disagreement about emotions, then, extending the perspective, b/ doubt cast on an emotional state, or finally c/ the construction of an emotion by linguistic means, by a speaker adressing a hearer who is just supposed to feel nothing or to feel differently of what he/she should feel in the speaker’s opinion.

Disgreement about an emotion, doubt cast on an emotion, construction of an emotion by linguistic means : all this implies that we’ll have to start with openly declared emotions. A clear distinction must be drawn between words and inner states, between what is really experienced (if anything is experienced at all) in a given situation and what is said to be experienced in this situation. This will be one of the permanent puzzling points of this investigation, and maybe even an irritating one. But, for sure, sometimes people say that they feel something and attribute feelings to other people.

Our basic object being the organization and development of dissensual, value-loaded discourses about expressed emotions, we’ll consider as basic data for this investigation discourses in which emotions are expressed, thematized and openly declared.

2. A method: Two ways to emotions

As there is a place for emotion in argument – she fired because she

was afraid – there is a place for argument in emotions :

(7)

A : – She was frightened by the young men shouting and running around

B : – But they were not threatening, they were rejoicing!

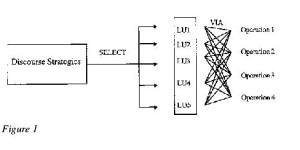

If we acknowledge the fact that the rightfulness or the legitimacy of an emotion can be called into question, that reasons for / against emotions can be given, we now have to give some thoughts to the specificity of this kind of discourse as argumentative discourse, namely to the characteristics of their conclusions and their arguments. Consequently, the program will run as follows :

– First, the general form of the conclusion has to be determined ; we have to know what kind of emotion is aimed at and who is the person affected : who feels / should feel what ? A core definition must be provided for this concept of conclusion, that will be called in what follows “emotion sentences”[vii].

– Second, what kind of arguments can be put forward to (de)legitimate such a conclusion ? Here we have to provide the basic guidelines along which the structure of a discourse oriented towards an “emotion sentence” can be investigated.

2.1 Emotion sentences : who feels what ?

An emotion sentence asserts or denies that a particular individual (who ?) is in the grip of a particular emotion, or in such and such psychological state (what ?). In linguistic terms an emotion sentence is defined as a sentence connecting an experiencer to an emotion term ; both of which must be defined.

Experiencers

Prototypical experiencers are human beings, so the basic set of potential experiencers corresponds to the list of [+Human] terms or phrases (terms referring to humans) : proper names, personal pronouns, definite descriptions. Animals can also be experiencers : a sad cow is not a sad landscape (the cow is sad, and maybe that makes you sad ; the landscape makes you sad). It might be interesting to study the emergence of animals as experiencers in our culture. Note that the speaker must be considered as an experiencer. If somebody says :

(8)

I think this is frightful news

Certainly the locutor (the linguistic being to which refers the first personal pronoun, and who is characterized by her ethos) is frightened ; and, by application of the sincerity rule, the emotion is ascribed to the speaker as a person.

(9)

This is frightful news

Here the news must be considered as frightening per se ; everybody should be frightened. The difficult question of the linguistic tools of empathy must be faced here.

From a practical point of view, a distinction must be drawn between experiencer and potential experiencer. The first move in investigating the emotional dimension of a discourse is to list the potential experiencers. For example, in (D2) the main potential experiencers are :

(10)

I

We

A list of positive individuals belonging to the we -set

The victims

The crazy men from Pale

A list of negative individuals associated to The crazy men of Pale – set The opponents :

our military and political leaders

As a rule, the potential experiencer will be designated by one of the terms mentioned in the text[viii]; no external (“neutral”) designation is needed. The set of terms or expression referring to one potential experiencer will be called the “designative paradigm” characterizing this actor. For example, in (D2) the “designative paradigm” of the crazy men from Pale is :

(11)

– some feudals who have mistaken this century for another / quelques féodaux qui se sont trompés de siècle

– some political leaders who have withdrawn into their own identity which quickly evolved into madness / quelques dirigeants politiques [qui] ont sombré dans un repli identitaire qui s’est vite transformé en folie

– the crazy men from Pale / les fous de Palé

– men who have interpreted in their own way what is sometimes called “the epic vertical” of the great medieval narratives / des hommes ayant interprété à leur manière ce que d’aucuns appellent la « verticale épique » des grands récits du Moyen Age

Emotion terms

Emotion terms can be defined or listed. The list includes probably some hundred of terms, basically the classical emotion terms, such as fear, anger, shame…, but not exclusively. For example the following predicates are emotion terms:

(12)

to piss sb off ; to be fed up…

Simple lists of terms of affect are very good instruments to start with ; they largely correspond to the lists provided by psychologists who pay attention to what they call “verbal labels attached to emotions”[ix] This basic set of emotion terms can be extended. Consider for example the sentence:

(13)

Peter was boiling

(13) contains no emotion term. But, for sure, the experiencer, Peter, really experiences something, and certainly not shame nor fear or joy ; maybe something like indignation, maybe impatience. Consequently, the emotion sentence associated to (13) will be : {Peter : /indignation/ /impatience/} – the slashes show that the emotion terms have been reconstructed and not directly taken in the text. Along these lines, some emotions can be easily identified on such purely lexical grounds. Other forms of extension are equally possible. The general conclusion is that a rich set of linguistic data can be exploited to reconstruct emotion terms.

Examples : Reconstructing emotion sentences

With these simple notions of experiencers, emotion terms and emotion sentences, we can have a look at a text or a corpus with our very simple question in mind : who experiences what ? In (D2), the emotion sentence determining the emotional orientation is given in the title of the paper:

(14)

The empty parts of France : the frightening figures / La France du vide : les chiffres qui font peur.

The emotion term is fear (peur), the experiencer /everybody/, so the reconstructed emotion sentence will be :

(14’){/everybody/, fear}.

(14’) determines the general emotional orientation, which will remain stable throughout the paper. The emotional situation is much more sophisticated in (D1), “Sarajevo : The Assassinated Citizenship”. The first reason is that the text stages several emotionally well differenciated experiencers:

– The enemies, the crazy men from Pale, feel a kind of joy.

– In our text, the class of the victims has not been qualified from the emotional point of view. This might be an important aspect helping to tell apart this kind of militant political intervention from horror tales.

– The opponents feel nothing, they are apathetic.

The second reason is that the we-class, which includes the ideal audience, is richly endowed with emotions, and goes through a series of emotional transformations in the address. At the beginning “we” adhere to the opponent’s thesis and is apathetic ; then the arguer turns this apathy into shame ; finally, the call for action having been accepted “we” feels proud. Let’s consider this process of emotional attribution in more detail. Consider (15), the first sentence of the text:

(15)

Bosnia has now been at war for more than nine months, and the consequences should make everyone’s conscience shudder / Cela fait plus de neuf mois que la Bosnie-Herzégovine connaît la guerre, et un bilan à faire frémir toutes les consciences.

The verb frémir [to shudder] denotes a kind physical vibration which can be determined by a physical or, as in this sentence, by a mental-linguistic emotional stimulus. The French language says frémir de joie [to quiver with joy], which is clearly inappropriate in the context “ – conscience” ; the same is true for frémir d’horreur [to shudder with horror]. The only possible interpretation is to be found in the series frémir d’indignation [to shiver with indignation]… So, the emotion sentence associated to (14) will be:

(15’){/everybody/, /indignation, anger/}.

Consider now the sentence (16):

(16)

Le rouge nous montera au visage et nous resterons muets devant les questions gênantes de nos enfants / We’ll become red in the face and we’ll remain speechless in reaction to our children’s questions

In French, colère [anger] and honte [shame] are linguistically associated with this kind of red which monte au visage [rises to the face] ; the coordinated sentence is a cliché associated to shame[x], never to anger. We get here two very different emotions : anger and shame. Applied to emotion denoting terms, the principle of coordination reduction excludes anger. So, the emotion sentence associated to (15) will be :

(16’){we, /shame/}.

This is not the end of the emotion story. Consider sentence (17):

(17)

It seems that no crime against humanity can shock us and that we are getting used to horror / Il semble qu’aucun crime contre l’humanité ne nous choque et que nous nous habituions à l’horreur.

“Not being shocked by any crime”, “getting used to horror” : this lack of affect can be rephrased as “being apathetic”. The third emotion sentence is:

(17’){we, /apathy/}

So, in a few lines, three different emotions are attributed to “we” : our interpretation is that this experiencer corresponds to the ideal audience, first apathetic (believing in the the discourse of the Opponents “our governments”, “our political and military leaders”) ; then convinced by the orator’s arguments, turning indignant. Different modalities are attributed to these two emotional states, “we” is apathetic when it should be indignant : this is a rather good definition of shame. Shame is a value-based emotion, an incentive to action ; and the last lines of the speech are in a very different emotional tone, something like pride:

(18)

Like us, [our guests] think that war criminals that have initiated the ethnic purification must know that they won’t remain unpunished / Comme nous, [nos invités] estiment que les cirminels de guerre qui ont entrepris la purification ethnique doivent savoir qu’ils ne resteront pas impunis.

Note that this sentence contains no emotion term. This suggests that radically different ways of reconstructing emotion must be considered now. I would suggest something like the following emotional stereotype : « the proposed action is basically in agreement with the deepest political value of the audience [so we must be proud to fight for such a goal] ». This stereotype corresponds to topos T6, which will be introduced in the next paragraph.

2.2 Pathemes: Emotional facets, principle, axes, topoi… argumentative features

The emotion sentence being reconstructed as previously mentioned, the emotional conclusions of the discourse are now at our disposal. We must now ask for what explains, justifies, or argues for… for this conclusion, what counts for a reason backing this conclusion, what makes the surrounding discourse coherent with it ? This construction / argumentation of emotion can be systematically investigated. The basic element of this reconstruction could be called “argumentative emotional features” (or “pathemes”, from “pathos”).

In this second phase of the work, emotions are not diagnosed from their subsequent manifestations, but constructed from their antecedents. If the discourse is emotionnally coherent, constructed emotion and diagnosed emotion coincide. In empathic communication, emotion is identified and transmitted both by expression and justification.

An event can be emotionally evaluated / constructed along the following emotional axes, roughly defined here as classical topoi considered in their relation with the experiencer as a person – a person being defined as a set of values.

(T1) Position of the event on the euphoric / dysphoric axes (pleasant/unpleasant) ? This position of the event can be directly asserted, or constructed along the following axes. Often both processes are used :

(19)

This consequence would be unpleasant (S1). Our interests would be harmed (S2)

Here the emotional quality of the event is first directly asserted in (S1), and then argued in (S2). According to the normal argumentative interpretation, (S2) is an argument for (S1).

(T2) Category of people affected ? Is there a link between these people and the experiencer ? For example, in our culture the maximal emotional investment is on children : “children/ordinary citizens are dying” is emotionally most efficient than “adults/militia are dying”. Here we are in the realm of emotions socio-culturally associated with different categories of people or groups (or emotional stereotypes, commonplaces or clichés, all these designations being not obligatorily pejorative). Such emotional inferences are necessary to account for the use of but in sentences like (20):

(20)

Children are dying from hunger, but that doesn’t move him The kind of person affected is not exclusively defined by such broad stereotypes. The link between these people and the experiencer plays an essential part in the construction of emotion : what affects a citizen of my country / my village, or my children, is more moving that what affects other people.

(T3) Analogy ? Is there a correspondance between the event to be emotionally evaluated / constructed and domains where emotion is socially / personally stabilized?

(T4) Quantity, intensity ? The bigger the number of victims, the bigger the shock – and the time on TV. It seems that this emotional parameter is not capable of creating emotion just to stress a pre-existing emotion. But big / small is beautiful and it seems that low/high quantity can create enthusiasm whatever the object may be (cf. The Book of Records).

(T5) What are the causes ? Who are the agents ? How are they linked to the (potential) experiencer’s interests, norms and values (personal / group / social)?

(T6) What are the consequences ? Do they affect the (potential) experiencer’s interests, norms and values?

(T7) Control? : Can the event be controlled by the (potential) experiencer?

(T8) Distance ? Spatio-temporal construction of the event ? Global distance from the (potential) experiencer ? This set of principles can be illustrated by examples taken from our corpus.[xi]

4. Illustration

4.1 Building an orientation towards /indignation/ : Text (D1) “Sarajevo : the assassinated Citizenship” (see the first paragraph in Annex).

This orientation is built in two moments : first as a kind of /horror/, associated with a dysphoric field ; then, by mentioning the agents, as /indignation/.

– Topos (T1) : the events are basically oriented towards the dysphoric side by the following terms and expressions :

(21)

war, dead, refugees / guerre, morts, réfugiés

(22)

camps where people are tortured and killed / des camps où l’on torture et massacre

– Topos (T2), Who ? Mainly civilians (vs military people, militia…)

(23)

80% civilians / 80% de civils

– Topos (T3), Analogy ? Second World War camps : (28) camps / des camps the biggest extermination enterprise since World War II / la plus grande entreprise d’extermination depuis la seconde guerre

– Topos (T4), Quantity ? Big quantity :

(24)

165 000 dead / 165 000 morts

(25)

tens of thousands of civilians trapped in camps / des dizaines de milliers de civils enfermés dans des camps

– Topos (T8), Distance ? Near :

(25)

under our eyes / sous nos yeux

(26)

to morrow … the day after tomorrow… / demain… après demain

This set of topoi builds a feeling of the type /horror/.

– Topos (T5), Cause and Agent ? The following designations are extracted from the designative paradigm (11) :

(27)

feudals who have mistaken this century for another / quelques féodaux qui se sont trompés de siècle political leaders… withdrawn into their identity… evolving into madness / dirigeants politiques…repli identitaire … folie the crazy men from Pale / les fous de Palé.

The reponsible agents are clearly designated (some of them are explicitly mentionned) ; they are the embodiment of counter-values for an experiencer posited as a “citizen” (cf. the title of the address) ; the situation calls for action. The feeling is turned from /horror/ into /indignation/. One last point : Starting from the same situation, other types of feelings could be rhetorically- argumentatively constructed, for example by a discourse locating the process far away somewhere in the Balkans, depicting the events as a tribal war, etc : this will create the orientation towards /apathy/ characterizing the Opponent’s discourse.

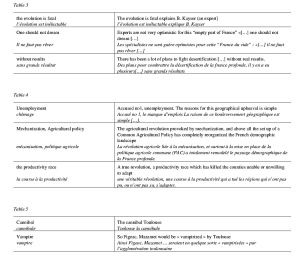

4.1 Building an orientation towards /fear/ : Text (D2) “The empty part of France : the frightening figures”. What are these “frightening figures”?

(28)

Two French people out of ten lived in town at the beginning of this century, five out ot ten after the Second World War, eight out of ten nowadays, that is to say 47 out of 58,5 millions of inhabitants of the Hexagon / Deux Français sur dix vivaient dans une ville au début du siècle, cinq sur dix après la seconde guerre mondiale, huit sur dix aujourd’hui, soit 47 des 58,5 millions d’habitants de l’Hexagone.

Is this “really” frightening ? A euphoric discourse could be very easily built on these figures : “France is no longer an outdated rural country, its main cities are now reaching a critical size, they are able to attract international investments…”. The option chosen by the paper is quite different, and clearly dysphoric. This negative picture is built according to the following topical lines.

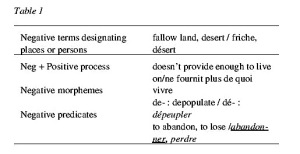

– Topos (T1) : The description of the “empty part of France” is built on basically dysphoric terms.

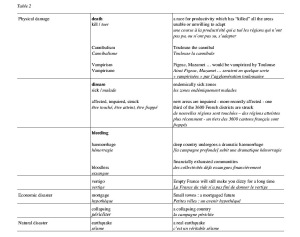

On this dysphoric basis, the specific feeling of “fear” is constructed along four “emotional lines”, or classical topoi : analogy, causality and control.

– Topos (T3), Like what ? Analogy turns more precisely this description towards fear by assignating to the dysphoric process an interpretation in the field of disease, death and disasters. The choice of such an interpretant for the described phenomenon commits to a certain conception of control (cf. infra, Topos T5).

(T7) Control ? The process escapes all real possibility of control.

– Topos (T5), Cause and Agent ? This “death” is attributed to abstract agents, “unemployment”, “mechanization”, “productivity race”.

Note the difference it would make if the agents were not these ones but for example :

(29)

The bureaucrats from Brussels

Mr So and So, our Minister of Agriculture

This second kind of agents might provide for grounds for a call to action or revolt ; in this case, the appropriate emotion would be /indignation/, not “fear”. This orientation towards non-political feelings is confirmed by a last set of fictional agents, “cannibals” and “vampires”.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, I have tried to show that argumentative situations can be considered basic for investigating the emotional dimension of discourse. The concept of emotion sentence has been defined. I have suggested that an experiencer- oriented set of emotional axes or topoi is basic for the construction / orientation of discourse towards emotion. The examples chosen show that these methods and notions are operative as regards real discourse. One important problem still has to be discussed : a set of basic emotions should be defined in agreement with the topical rules ; such a definition would be rhetorical, that is based on stereotypes or commonplaces (cf. Aristotle’s Rhetoric, Book 2).

Annex : Text (D1) :

Sarajevo : la citoyenneté assassinée Cela fait plus de neuf mois que la Bosnie-Herzégovine connaît la guerre, et un bilan à faire frémir toutes les consciences : 165000 morts, dont 80% de civils, plus de 9 millions de réfugiés et des dizaines de milliers de civils enfermés dans des camps dont certains – cela a été prouvé – sont des camps où l’on torture et massacre. Sous nos yeux e déroule la plus grande entreprise de nettoyage ethnique depuis la dernière guerre. Demain il suffit au général hiver d’intervenir à sa manière pour achever le programme de nettoyage entrepris par quelques féodaux qui se sont trompés de siècle. Et lorsque après-demain, quand il faudra faire les compte, nous réaliserons la quantité de dégâts humains causés par la folie nationaliste, le rouge nous montera au visage et nous resterons muet devant les questions gênantes de nos enfants.

Impuissance de nos gouvernants, démobilisation de l’opinion, l’Europe reste interdite. Il semble que plus aucun crime contre l’humanité ne nous choque et que nous nous habituions à l’horreur Contrairement à ce que les responsables politiques et militaires occidentaux tentent de nous faire croire […].

Bosnia has now been at war for more than nine months, and the consequences should make everyone’s conscience shudder : 165 000 dead of whom 80% are civilians, more than 9 millions refugees and tens of thousands of civilians trapped in camps some of which are – it has been proved – camps where people are tortured and massacred. Under our eyes the biggest enterprise of ethnic purification since World War II is in progress. Tomorrow “general winter” has only to intervene in its own way to complete this cleaning program initiated by some feudals who have mistaken this century for another. And when, the day after tomorrow we’ll have to take stock, we’ll realize the quantity of human damages provoked by nationalist madness, we’ll become red in the face and we’ll remain speechless in reaction to our children’s embarrasing questions. Ineffectiveness of our governments, demobilization of our governments, Europe remains mute. It seems that no crime against humanity can shock us and that we are getting used to horror. Contrary to what our political and military leaders try to make us believe […]

NOTES

[i] This is not to deny the importance of a critical approach to emotions; it could even be argued that an investigation of the linguistic – rhetorical dimension of emotions is basic for a real education of emotions, particularly in public life.

[ii] This paragraph deals with my “external hypotheses”; the following one with my “internal hypotheses”. These two kinds of hypotheses must be distinguished; cf. Ducrot, Les mots du discours, Paris: Le Seuil, 1980, p. 20; the concept can be traced back to the philosopher Pierre Duhem (1861-1916). Internal hypotheses are intra-theoretical hypotheses, and are currently considered as the only kind of hypotheses on which a theory is built. The external hypotheses are the set of hypotheses made on the object of investigation. Internal hypotheses are not independant of external hypotheses. In our field, a much needed reflexion of argumentative genres, or on the method for collecting corpora would be instrumental to the constitution of an (explicit) set of external hypotheses.

[iii] My examples are taken from French, and the method implies that one has to stick to the original linguistic data. An approximative translation is provided.

[iv] If her argumentation succeeds, she will have convinced A that he should be afraid. Will A really be afraid? Maybe she will, but this is another question. I should believe but I don’t; I should do, but I don’t; I should feel, but I don’t: I certainly know, but nonetheless … Je sais bien, mais quand même.

[v] The utterance “Let’s rejoice, the tyrant is dead! ” refers to the dead person, X via the nominalized predicate “is a tyrant”, and the conclusion follows analytically from the argument, in virtue of the common place “One must rejoice when a tyrant is dead” (“one must cry when a tyrant is dead”). Idem, mutatis mutandis, for the other case. In other words, when X is dead, under the predicate “is a tyrant” one rejoices; under the predicate “is the father of our country” , one cries; cf. Plantin, 1996: 58 on this kind of hologrammatic phenomenon.

[vi] This might be characteristic of a genre of political discourse, and/or of a period in time.

[vii] The expression “emotion sentence” translates “énoncé d’émotion”. It conveys a different meaning from “emotional sentence”.

[viii] Quotations from (D1) and (D2) are underlined.

[ix] For the French language Cosnier (1994) has provided a list of basic emotion terms in French language and culture. The fact is that the linguist list and the psychologist list do coincide.

[x] American-English informants tell that the expression “to become red in the face”is associated with anger or shame/embarrassment, and “blood coming up to the brow”associated with anger only.

[xi] To quote fully (D1) and (D2) is not possible here. See a less incomplete analysis in Plantin 1997.

REFERENCES

Balibar-Mrabti A. (ed.) (1995). Grammaire des sentiments, Langue Française 105.

Battachi M. W., Th. Suslow, M. Renna (1996). Emotion und Sprache. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Caffi Cl. & R. W. Janney (1994). Toward a pragmatics of emotive communication. Journal of pragmatics 22, 325-373.

Cosnier J. (1994). Psychologie des émotions et des sentiments. Paris : Retz.

Fiehler R. (1990). Kommunikation und Emotion. Theoretische und empirische Untersuchungen zur Rolle der Emotionen in der verbalen Interaktion. Berlin/NexYork : de Gruyter.

Gross M. (1995). Une grammaire locale de l’expression des sentiments. Langue Française 105, 70-87.

Hoffman M. L. (1984). Interaction of affect and cognition in empathy. In: Izard C. E., J. Kagan & R. B. Zajonc, Emotions, cognition and behavior. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 103-131.

Kövecses Z. (1990). Emotion concepts. New York : Springer Kerbrat-Orecchioni.

C. (1980). L’énonciation De la subjectivitédans le langage. Paris : A. Colin.

Lausberg H. (1960). Handbuch der literarischen Rhetorik. Munich: Max Hueber.

Lewis M. (1993). Self-conscious emotions : embarrassment, pride, shame and guilt. In LEWIS M. & J. M. HAVILAND, (eds), Handbook of emotions. New York : Guilford Press, 563-573.

Plantin Ch. (1996). L’argumentation. Paris : Le Seuil (“Mémo”).

Plantin Ch. (1997). L’argumentation dans l’émotion. Pratiques 96, 81-100.

Plantin Ch. (to appear a). Les raisons des émotions. In M. Bondi (Ed.), Forms of argumentative discourse / Per un’analisi linguistica dell’argomentare, Bologne.

Plantin Ch. (to appear b). La construction rhétorique des émotions. Proceedings of the 1997 IADA conference in Lugano Rhétorique et argumentation.

Plantin Ch. (to appear c). “Se mettre en colère en justifiant sa colère”. Proceedings of the conference Les émotions dans les interactions communicatives, Lyon 1997.

Rimé B. & K. Scherer (éds) (1993). Les émotions. Neuchâtel : Delachaux et Niestlé (1st ed. 1989).

Scherer K. R. (1984a). Les émotions : Fonctions et composantes. Cahiers de psychologie cognitive, 4, 9-39.

Scherer K. R. (1984b). On the Nature and function of emotion : A component process approach. In Scherer K. R., & P. Ekman (eds) (1984). Approaches to emotions. Hillsdale, N. J. : Lawrence Erlbaum. 293-317.

Ungerer F. (1995). Emotions and emotional language in English and German news stories. In S. Niemeyer et Dirven (eds), The Language of emotion. Amsterdam/Philadelphia John Benjamins. 307-328.

Walton D. (1992). The place of emotions in argument. University Park : The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Walton D. (1997). Appeal to Pity. Albany : State University of New York Press.