ISSA Proceedings 2014 – Consideration On The Notion Of Reasoning

Abstract: I started my discussion from Ralph H. Johnson’s view, and examined the phenomenon that theorists have used the notion of reasoning in different way and tried to explain why they use it in a confusing manner. I compared the notion of reasoning with the notions of argument and argumentation. I also pointed out some misunderstood concepts related to reasoning, such as soundness, completeness and validity. And hence proposed a new definition of reasoning.

Keywords: Argument, Argumentation, Reasoning

1. Introduction

It is known to us that informal logic has been developed over thirty years since the late 1970s last century. During decades, discussions that mainly concerns on the issues on interpretation, construction and evaluation of argumentation have led to remarkable accomplishment. Although they first started from the demand of pedagogical reform that launched by students and teachers in universities of Canada by rejecting the way symbolic logic treated to our daily arguments, these research were carried out from distinct perspectives, and rapidly developed in north America, Europe and now Asia. Gradually researchers gained accumulated agreement that the strict and artificial symbolic language only can never be enough for us to construct and evaluate arguments in natural discourse.

And argumentation theory has been benefited from examining the way we look at logic. Under this naturalizing turn of logic, reasoning has also been studied from a different manner than what traditional symbolic logic has done. Not only did researchers start to pay attention to those who deduction and probability were hard to resolve, but among them, they incorporate a number of various reasoning types to reasonable use in different contexts.

However, although the discussion of reasoning has all the way accompany discussion on argumentation theory (a broad sense including informal logic so), it is still far away from what we should achieve. As Ralph Johnson has pointed out, if we type “the theory of reasoning” and try to look up through The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, then we will find no entry, nor standard indices of The Philosopher’s Index, whereas the other related concepts are given intensive discussion, say, “rationality” (Johnson, 2000). As we have seen, although different reasoning under different contexts has been studied under the title of informal reasoning, there is still little research on the notion reasoning itself from a perspective of philosophy. However, understanding reasoning means not only how much we know about itself, but also vital in understanding the other related concepts. As Johnson also pointed out the First Form of Network problem, it is significant for us to understand the concept and the interrelationship of critical thinking, problem solving, metacognition, argumentation, informal logic and reasoning (Johnson, 2000). And only in understanding these definition and interrelationship of them all can we situate what we have known in a comprehensive and confusion-avoiding location, which leads to the Second Form of Network Problem “How does reasoning relate to argumentation? How is reasoning related to rationality? to intelligence? to knowledge? to thinking? to argument?”[i]And to constitute a “theory of reasoning”, Johnson made a list for us to answer:

1. What is reasoning? Is reasoning either identical to, essentially the same as, or else reducible to, inference, implication, and entailment… How does reasoning differ from thinking?

2. What is the relationship between reasoning and rationality? Are they the same concept under different guises? And what about reasoning and intelligence? reasoning and knowledge?

3. Is there a discernible pattern in the historical development of the various exemplifications of reasoning? And what can we learn from various historical theories of reasoning?

4. Are there universal principles of reasoning? Or are substantive principles of reasoning always field dependent?

5. What is an appropriate conceptual scheme (or framework) for the theory of reasoning? How can reasoning be most plainly categorized?

6. What are the criteria of adequacy that a theory of reasoning must satisfy?[ii]

Beside Johnson, Finocchiaro also had clarified what he called the theory of reasoning “By theory of reasoning I mean the attempt to formulate, to test, to clarify, and to systematize concepts and principles for the interpretation, the evaluation and the sound practice of reasoning. I claim that the theory of reasoning so defined is a legitimate philosophical enterprise which is both viable and important. ” (1984, p. 3). To sum up, if there is anything we call “theory of reasoning”, then the first issue for us to approach is to answer the question “what is the notion of reasoning?”

2. The popular definitions of reasoning

2.1 Operational view

In realm of formal logic, reasoning and argument have been defined as a sequence of formulas, the very last of which is conclusion and the remainders are premises. Each formula comes either from the set of axioms or follows from the previous members by application of specific reasoning rules. This definition is widely applied in various branches of symbolic logic, and even has been regarded as a standard definition in logic to introduce into other disciplines. There are also, although privately, some logicians even believe that the application of reasoning rules themselves is already reasoning, for instance, modus ponens. However, more commonly, logicians treat reasoning and argument as the same thing; and they have no interest in differentiating these two notions. These logicians hold the view that it makes no sense in distinguishing reasoning and argument as they have little difference in the dealing way in symbolic language system, in that all the corresponding natural language have been abstracted into formulas composed of mere variables and connectives that represent specific meaning.

According to this, reasoning as well as argument can be classified into different categories, by criteria that how strong the link between premises and the conclusion. Hence, we have deduction and induction. By deduction, it refers to those reasoning whose conclusion follows necessarily from premises that have been known as true; while by induction, it refers to reasoning that the conclusion is probably true, instead of being necessarily true, if their premises are true.

Looking at this point of view, we can see that scholars agree on it regard reasoning as purely abstract operation (or calculation). It is by no means that I am denying that reasoning has close relationship with abstract calculation, however, in daily life, there is not a single kind of real reasoning can be carried out regardless of real subject and real environment that subject has been situated. For instance, we can of course complete an abstract operation of mathematical proof by systematic calculation. However, we must complete it out of some real reasons. We may do it to complete our homework, or to satisfy our curiosity, or sometimes just for time-killing. But any reason is out of human practical purpose, which means real reasoning that conducted by human subject can never be separated from practical appeals. This is to say, by real reasoning, it by no means equals to abstract mathematical operation, rather, it is a kind of practical activity that also closely related to pragmatic environment and specific context. This also explained that why results from psychological experiments went so against logic.[iii] Although formal logicians regard reasoning as pure abstract operation through their normative concern and characteristic of discipline, if we treat the operation view as the only legitimate manner to study reasoning, we simply overlooked the diversity and flexibility of human reasoning in real life. And real reasoning has so much for us to explore, it deserves a new and complete consideration of its notion.

2.2 Inferential view

Unlike formal logicians who concentrate on transformation of logical structure between statement forms and the truth-value calculation of formulas in symbolic system, informal logicians paid more attention on considering the content and context of reasoning from a pragmatic point of view. One popular point of view goes that reasoning is inference, or a sequence of inference. Take these definitions for example,

Dagobert D. Runes:

“Reasoning is the process of inference; it is the process of passing from certain propositions already known or assumed to be true, to another truth distinct from them but following from them; it is a discourse or argument which infers one proposition from another, or from a group of others having some common elements between them.”[iv]

Douglas Walton:

“Reasoning is the making or granting of assumptions called premises and the process of moving toward conclusions (end points) from these assumptions by means of warrants.”[v]

Stephen Toulmin:

“The term reasoning will be used, more narrowly, for the central activity of presenting the reasons in support of a claim, so as to show how those reasons succeed in giving strength to the claim.”[vi]

These definitions seem that they emphasized the centre status of the roll that inference played in process of reasoning, and supporting structure played in inference. Beside the scholars I mentioned above, Jaakko Hintikka, C.L. Hamblin are also on the list, which reflects how popular this point of view is. However, it seems to me that, the definition that defines reasoning to inference or superimposition of inference seems too narrow, which reminds us to be vigilant. According to Johnson, inference is “the transition of the mind from one proposition to another in accordance with some principle; at its best, guided by the theory of probability.”[vii] If we admit reasoning equals to inference, then we simply overlooked the fact that reasoning can be very flexible. Reasoning can not only be proceeded forward to the product of our mind, but also backward to the state of mind that can complete our problem space. For instance, problem solving is very typical. In many cases we search the arithmetic from not only beginning stage to end stage, but also do it inversely to search problem space. And sometimes it even goes circular, like A ⊨ A. And second, reasoning can repeat, stop and restart whenever the subject wants to, for

instance, mathematical calculation. If we calculate the value of n in equation “n = m+1”, we can start from wherever “m = 1, n = 2; m = 2, n = 3; m = 3, n = 4……” or stop whenever we like to stop in this sequence. And if it is in need, we can surely repeat the process from necessary part. And third, reasoning can conduct not only in language but also on image, and sometimes reasoning on image can speed up our reaction. Fourth, reasoning can correct itself, and correctional reasoning takes place frequently among our everyday life.

So the question is, can inference behave the same all? Or, even if it can, do inference and reasoning follow the same process or proceed in same mental mechanism? The answer to these questions would be very tricky and it is better for us to combine the related discipline’s results, say, cognitive psychology. However, before that, we have to be careful with this inferential view.

3. Conceptual confusion

Till now, it seems that the notion of reasoning has been confused with a bunch of related concepts. Among those concepts I see argument is a highly appearing term. If we look at the views we have discussed above, it would not be surprise for us to see the confusion between the notion of argument and reasoning. In fact, not only in formal logic, but also in informal logic it has also been full of this conceptual confusion. For instance Toulmin (1984), after defined “reasoning” as I mentioned above, he immediately offered his definition of “argument”, which says “An argument, in the sense of a train of reasoning, is the sequence of interlinked claims and reasons that, between them, establish the content and force of the position for which a particular speaker is arguing.” From here we can observe, for Toulmin, the chain of inference makes reasoning, and the chain of reasoning makes argument. This point of view is endorsed by countless scholars which spreaded widely within informal logic. It seems make sense in the first place. However, if inference cannot be as equal as the only component of reasoning as we had expected, then how come the longer length and larger size of reasoning makes argument? If the notion of reasoning and the notion of argument only differ in its complexity, then what is the distinction between these two in nature?

The problem lies whenever we mentioned the notion of reasoning, we seldom really separate it from the notion of argument. There are countless logic textbooks starting with introduction to argument and then immediately tell students that reasoning can be classified as deduction and induction… as if “argument” and “reasoning” are the same words which can be used in turn. No matter in formal logic and informal logic, the notion of reasoning has all the way been bundled with the notion of argument. However, even we often try to convince other people by displaying our line of reasoning, it by no means that they are the same thing essentially in equal. One can surely experience that we always reason before we argue. And even Newton had indeed been hit by an apple which inspired him the law of gravity, he would never had composed his paper by the way he was inspired. Instead, he would certainly choose the normative treatment according to his own discipline. Why? Because reasoning is different from arguing.

Besides, if we trace the earlier root of history all the way back to this confusion, we would find that even in Aristotle’s works, he also used these two terms as interchangeable, although he did distinguish reasoning and argument. And hence Aristotle influenced all the way that we look at reasoning and argument.

4. Clarification

In order to clarify this confusion, we still have to return to formal logic, where validity has been complained quite a lot since last century. If we look at formal logic, no matter proposition logic, predicate logic, or non-monotonic logic, although formal logicians had studied logic by making use of symbolic mathematical treatment, their research object are human reasoning with distinctive characteristics, instead of single argument in everyday life. Precisely, what they study is the abstract form of reasoning; and symbolic systems are used to simulate the specific reasoning phenomenon with different characteristics. Theoretically, anyone can construct a symbolic system without considering its interpretation meaning. If all the propositions of this system are valid under the semantic interpretation that the system tried to describe and simulate, then it means this system successfully re-displayed this kind of reasoning phenomenon that the system tried to simulate. And in turn, if all the semantic interpretation can find its corresponding proposition within formal system, it means that the system constructed can completely show the reasoning phenomenon that the system intends to simulate. In this sense, formal logic used strict mathematical tools to describe, simulate and predict the different characteristics of reasoning phenomenon. And validity should be understood as the micro nature of both syntactic system and semantic model. It functioned as a kind of media which connects and guarantees the macro nature of symbolic system constructed can fit its semantic interpretation very well. In other words, what formal logic study is reasoning, instead of argument as informal logicians have focused on. Therefore, the term “validity”, “soundness” and “completeness” should be understood from the macro nature of logic system and its corresponding semantic interpretation that the formal system tries to capture. However, those criticisms from informal logicians had mixed the difference between reasoning form that formal logicians focused on and the real arguments that we come across in daily life. For instance, if we take A ⊨ A as an argument, then it surely is not a successful one, however, if we take it as a piece of self-evident reasoning, then no one can deny it is no wrong.

As Johnson had pointed out, if we want to clarify the notion of reasoning, then it is better for us to understand it in a network of its related concepts. To understand the notion of reasoning, one has to understand its relationship with argument, as well as the relationship with argumentation. To free the notion of reasoning from the bundling of argument, I think there are some key points that we have to consider:

– Reasoning is a mental process. Although logicians may feel uneasy about this point as it seems drifted away from encompass of logic, we have to face it. In saying so, one must realize that the notion of reasoning has become into a broad sense. The truth is, the notion of reasoning was too narrow from what I have discussed above. And this narrowness seriously hindered our understanding of reasoning and placed a lot of terms that caused confusion in degree. For instance, under the previous narrow sense of reasoning, problem solving, critical thinking and argumentation would seem close but still difficult to explain each other in a proper relationship. However, under this broad sense of reasoning, these concepts would be covered as application of reasoning practice that conducted through the product of reasoning, which will be discussed later. Only in admitting this, can we make distinction between reasoning and argument, in that, argument, no matter oral or written, is a kind of product of reasoning process. While argumentation is essentially a kind of social activity that is the application of the product of reasoning.

– Reasoning has practical purpose which leads reasoning to be situated in diverse contexts. As we have discussed before, in real life, there is no such reasoning can be conducted without any practical purpose, even conducting mathematical proof. This is to say, to study reasoning under different titles requires exploration that differs from formal logic which focused on the nature of symbolic system and its corresponding interpretation; rather, we should take more things into account as the research for real reasoning process can never be satisfied with the only mathematical treatment. And real reasoning is real because it conducted in a real environment that lots of factors have to be taken into account. This is to say, as Finocchiaro had proposed, if there is anything can be called the theory of reasoning, it has to incorporate “the attempt to formulate, to test, to clarify, and to systematize concepts and principles for the interpretation, the evaluation and the sound practice of reasoning.”[viii]

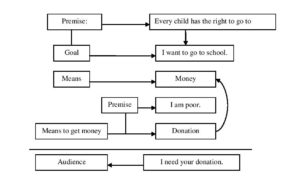

– Reasoning seeks to obtain products of mind which can be belief, argument, plan, solution, and image, etc. This explained why people prefer to persuade others by displaying their reasoning line, as it is an effective convincing method by simply revealing how they arrive at their mental product. This is to say, reasoning differs from argument in persuasion. Argument aims to convince other people that might disagree with the arguer, but reasoning has no such function, in that reasoning is only proceeded to arrive something. If anything is in charge of being convincing, that’s argument. So, construct argument means selecting useful things among all sorts of reasoning products. And it can explain why the theory of argument always related to dialectics and pragmatics, for they are all related to convincing.

– Reasoning has operation (or calculation) level. Cognitive psychology has proved that human can conduct mental operation by not only language but also image. This also explains why for many years formal logic has been taken as the born legitimate discipline aims to study reasoning and why visual image could also influence our state and product of mind. Although real reasoning takes place everywhere in our life, we surely have the ability to calculate or to operate on abstract state of mind while conducting reasoning. And by operation and calculation, we obtain our thinking product. However, the quality of this ability differs from context to practical environment which reasoning is being conducted.

What is reasoning? After so much discussion, it is time for us to consider the notion of reasoning from a distinctive perspective. In saying reasoning in the realm of informal logic, it is a kind of mental process which proceeds through mental operation to arrive at thinking products under practical environment. This seems like a descriptive definition; however, it helps us to understand reasoning under a real and broad environment of our daily life. And in saying theory of reasoning, it aims to capture and explain the conceptual natures and principles of reasoning that is conducted by real subject in pragmatic environment; it aims to formulate, interpret and evaluate the practice of reasoning.

5. Conclusion

Although for all the time, the notion of reasoning has been used in a very narrow sense while the notion of argument to the contrary very broad, we finally have to clear up the conceptual confusion that caused from this narrowness. To better understand reasoning, we should look at formal logic from a fair angle and check its definition by contrast of argument and argumentation.

Finally I discussed the fundamental natures that reasoning has, and explained the new definition of reasoning and the main contents that a theory of reasoning should cover.

To sum up, the theory of reasoning comes from also the philosophical demand and the practical needs of our understanding of real reasoning that takes place in everyday life. In this point, it has no conflict with formal logic treatment as they function differently in study of reasoning. Formal logic is more interested in abstracting the mathematical rules of human reasoning phenomenon; and the theory of reasoning is interested in understanding real reasoning with its relationship of the related concepts and practical application in real life.

To complete informal logic, the theory of reasoning plays significant role in the development of the theory of argument and argumentation, only in clarity of the fundamental issues of reasoning that the related concepts can gain greater progress in understanding themselves.

Besides, the theory of reasoning should be friendly with its related disciplines as cognitive science needs a cooperative work. And in doing this, it can explain the conflict conclusions that are from research of distinctive disciplines. In this sense, the theory of reasoning can function as bridge for us to coordinate with each related disciplines. In turn, the development of other subjects can also help us understand reasoning.

NOTES

i. Johnson, & H. Manifest Rationality: A Pragmatic Theory of Argument, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, (2000), 23.

ii. ibid. 97.

iii. Dunbar, G. L.Traces of reasoning with pragmatic schemas, Thinking & Reasoning (2000), 6:2, 173-181.

iv. Dagobert D. Runes, Dictionary of Philosophy, Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Allanheld, (1984). 281.

v. Douglas. Walton, WHAT IS REASONING? WHAT IS AN ARGUMENT? Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 87, (1990), 403.

vi. Stephen Toulmin, Richard Rieke, Allan Janik, An introduction to reasoning, 2nd edition, New York, Macmillan Publishing Company (1984).14.

vii. Johnson, & H. Manifest Rationality: A Pragmatic Theory of Argument, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, (2000), 94.

viii. Maurice A. Finocchiaro Informal Logic and the Theory of Reasoning, Informal Logic, Vol.6, (1984), 4.

References

Aristotle (2010). The works of Aristotle. Translated into English under the editorship of W.D. Ross. Oxford: Nabu Press.

Dunbar, G. L (2000). Traces of reasoning with pragmatic schemas, Thinking & Reasoning, 6:2, 173-181.

Eemeren, F. H. van & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The pragma-dialectical approach, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Finocchiaro, M. A. (1984). Informal Logic and the Theory of Reasoning, Informal Logic, 6, 3-7.

Hamilton, A. G. (1988). Logic for Mathematicians, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd.

Johnson, & H. (2000). Manifest Rationality: A Pragmatic Theory of Argument, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Runes, D.D. (1984). Dictionary of Philosophy, Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Allanheld.

Toulmin, S. E. & Rieke, R & Janik, A (1984). An introduction to reasoning, 2nd edition, New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Walton, D. (1990). What is reasoning? What is an argument? Journal of Philosophy, 87 , 399-419