ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ Persuasion,Visual Rhetoric And Visual Argumentation

Abstract: It is often said that images are excellent persuasive means. However, if images are persuasive, can they also be argumentative? After discussing authors who have tried to fill the gap between rhetoric and argumentation (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, Reboul, Bonhomme), I will argue that the same figures or tropes can have both a persuasive and an argumentative function.

Keywords: metonymy, persuasion, visual argumentation, visual rhetoric.

1. Introduction

The relationship between visual rhetoric and visual argumentation is a topic to which several essays have been dedicated. Some scholars deal with it in a general way (Blair, 2004; Kjeldsen 2012). Others focus on figures or tropes in particular (for antithesis, van Belle, 2009). Indeed, it has becoming a sub-field in the domain of visual argumentation. That said, the way in which visual rhetoric and visual argumentation have been related is not completely satisfactory. I will try to show that most attempts to link rhetoric and argumentation are based on the assumption that figures of rhetoric are above all persuasive. This assumption has a dramatic consequence upon visual argumentation, specifically because one argument against visual argumentation is that images are merely persuasive. As a result, considering visual rhetoric as persuasive would not reinforce visual argumentation, but rather critiques against it. Furthermore, another critique must be taken into account: in the frequent case of mixed media, i.e. when an argument is displayed in both words and images (such as in ads or commercials), the text alone is supposed to be argumentative, while the image would be merely persuasive (Adam & Bonhomme, 2005, p. 194 & 217).

So, in the first part of this paper, I will examine some of the principal ways figures of rhetoric and argumentation have been related in order to determine the extent to which figures have been considered as arguments. Then, in the second part, I will argue that some figures of rhetoric can be persuasive and argumentative at the same time.

Simply stated, I am interested in the argumentativity of figures. In saying this, I am using a French concept (argumentativité) that was coined by Ducrot and is used in the French theory of argumentation in order to refer to figures (Bonhomme, 2009; Plantin, 2009). This concept essentially suggests that an utterance can have an argumentative value instead of being limited to providing merely informational value (Anscombre et Ducrot, 1986, p. 91). Such an argumentative value comes from the fact that we can find, in an enunciate, elements that allow for a given conclusion by way of a commonplace, which Ducrot calls a topos (Ducrot, 1992). However, this concept is used in a slightly different way when applied to figures: in this case, it refers to their argumentative value, which can be considered as persuasive or argumentative, in this case when figures provide reasons to support a claim. Note that in what follows, I use the adjective “argumentative” with this restrictive meaning, unlike those who use it in a broader way, i.e. including all mean of influencing the addressee.[i]

Yet, why is the issue of the argumentativity of figures so important? Simply put, if figures are considered to mainly have a persuasive role, it is hardly possible to see them as arguments, at least for those who believe argumentation and persuasion are mutually exclusive (Plantin 2012; Doury 2012; Micheli 2012).

It is generally accepted that persuasion is an important feature of images (Scott & Batra, 2003). It seems even that the syntagm “visual persuasion” is almost pleonastic since the supposed “essence” of image is closely related to persuasion (Hill, 2004). The problem, however, is that this understanding of images as persuasive does not have a positive connotation, as it is very often linked to propaganda. Propaganda and persuasion are indeed often seen as techniques for manipulating (Jowell & O’Donnel, 1992 ; Pratkanis & Aronson, 2001; Spangenburg & Moser, 2002), in particular regarding political posters (Seidman 2008) as well as advertising (Messaris 1997). This shows that we must be very careful when dealing with issues of visual persuasion. As we will see, this is all the more the case because figures of rhetoric are usually considered as persuasive, at least in French scholarship.

2. Figures of rhetoric and arguments

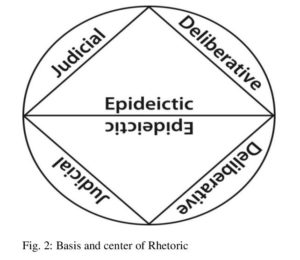

2.1 Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca

Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca are amongst the first to have drawn our attention to the relationship between figures of rhetoric and argumentation. These scholars were indeed interested in “showing why and how the use of certain figures of rhetoric can be explained by the need for argumentation” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 227). At its core, their theory aims to call into question the old understanding of figures of rhetoric as pure ornament, i.e. without any other function than “embellishment”. This would explain their need to distinguish between times when a figure is purely ornamental, and those when it may play a part in an argumentative process. For this reason, they consider “a figure to be argumentative if it brings about a change of perspective, and its use seems normal in relation to its new situation. If, on the other hand, the speech does not bring about the adherence of the hearer […], the figure will be considered an embellishment, a figure of style” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 229; authors’ emphasis).

To be sure, the idea of considering figures from an argumentative standpoint was an important step forward for the field. However, it is insufficient to say that a figure is argumentative simply if it is accepted. Insofar as Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca consider that “the same figure, recognizable from its structure, doesn’t necessarily produce the same argumentative effect” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 232), they proposed their own classification of figures, aimed at emphasizing how figures can help argumentation. They organized figures into three categories: choice, presence, and communion. Indeed, this classification has the purpose of showing that “the effect, or one of the effects, certain figures have in the presentation of data is to impose or suggest a choice, to increase the impression of presence, or to bring about communion with the audience” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 232-233).

From this point of view, figures are considered as argumentative if they increase the adherence of the audience, which is a consequence of the concept of argumentation developed by Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, i.e. a concept aimed toward influencing a given audience (Plantin, 1990, p. 16).

2.1.1 Hypotyposis

Interestingly, the first example of a figure they give is hypotyposis. This figure has a lot to do with images. According to Fontanier, for instance, “Hypotyposis paints things in a such a lively and dynamic way that it puts them, so to say, in front of our eyes and turns a narrative or a description into an image, a painting, a tableau vivant” (Fontanier, 1968, p. 390). They comment on this figure by writing: “It is therefore a way of describing events that make them present to our conscience. Could we negate the eminent part it plays as a factor of persuasion?” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 226). And they added: “If we neglect this argumentative role played by figures, their study will quickly be a vain hobby”.

We can see in this quotation that hypotyposis is considered as a factor of persuasion. In turn, persuasion is assimilated to the argumentative role played by figures. The aim of the chapter on the relationship between figures of rhetoric and argumentation is indeed “to resituate argumentation figures in their proper place concerning the phenomenon of persuasion” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 231). Such a conception is not surprising, given that Perelman aims to reconcile rhetoric and argumentation. But it has, however, important consequences. From my point of view, playing a persuasive role is not enough to warrant seeing a figure as argumentative. If hypotyposis is eminently visual, we need to be sure that, beyond its effectiveness, it is also argumentative.

Yet within Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s own classification of figures, hypotyposis belongs to the category of figures of presence. Besides hypotyposis, other figures belong to the same category: ekphrasis and energeia, among others, since they have the same purpose: namely, to make the object of the discourse present (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 235). However, once again, if such a figure is highly persuasive and contributes to the effectiveness of the discourse, is it also argumentative? I am not sure it is.

As we know, presence is very often visual. A well-known example of energeia – that Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca use when dealing with “presence” – is that of Caesar’s bloody tunic. This is a classic example that illustrates the use of concrete objects to move the audience (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 157). Once more, I wonder whether such a very persuasive device can be considered as argumentative, since it is explicitly intended to move the audience through an appeal to pity. Aristotle described energeia as vividness, liveliness, “bringing-before-the-eyes”, (Rhetoric 1411b 24), but also limited its use and that of similar figures in so far as “it is not right to pervert the judge by moving him to anger or envy or pity” (Aristotle, Rhetoric 1354a 24-26). Unlike Cicero, Quintilian also wished to limit its use in courts (Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, VI, 2, 1).

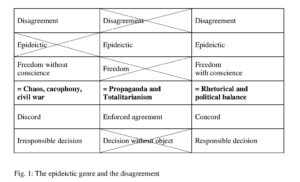

2.1.2 Phryne

A famous example of a similar rhetoric device is that of Phryne, a Greek courtesan known for her beauty. It has been said that Praxiteles used her as a model for his famous Aphrodite of Knide. She is also known for the legendary trial in which she was probably charged with impiety. According to some of the sources, such as Quintilian (Institutio Oratoria, II, 15, 9), the trail had a surprising turn of events. Just when it seemed that the verdict would be condemnation, her lawyer, Hypereides, (who was also, by the way, one of her lovers), removed Phryne’s robe and bore her breasts before the judges. Awe-struck by her beauty, and undoubtedly impressed with a sense of pity, they acquitted her.

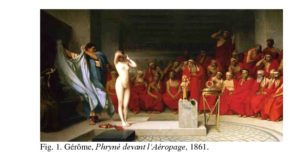

The anecdote soon became a topos used to illustrate the persuasive power of rhetoric in Greek and Latin rhetoric treatises (Vouilloux, 1995, p. 102 & 109). It also illustrates quite well an appeal to pity based on sight (Lévy & Pernot, 1997, p. 6). For this reason, it is known to have inspired painters, like Baudouin and Gérôme (fig. 1).

Not surprisingly, Gérôme’s painting has been used as an illustration in books on rhetoric and persuasion (fig. 2 & 3).

This shows again that we must be very careful when dealing with visual rhetoric and its relationship to argumentation. Hypotyposis and energeia belong, as we said, to figures of presence according to Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s classification. However, increasing the feeling of presence (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 236) is not necessarily an argumentative tool. To round up the story about Phryne, it’s worth noting that after her acquittal, Athens published an official decree forbidding the use of the “appeal to pity” figure, in particular by exposing an accused individual to the judges (Lévy & Pernot, 1997, p. 6).

Once again, why is presence so effective? It must be said that the word “presence” is rather deceiving in this usage. For Perelman, it is important because it makes something more present and “enhance[s] the value of some of the elements of which one has actually been made conscious” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 235). This is true. However, why is visual presence so effective? One way of understanding this effect is that presence is evident, or even self-evident. It should be noted that the effect of presence can also be rendered by another rhetorical tool, enargeia, sometimes confused with energeia[ii]. Interestingly, when Cicero translated enargeia from Greek, he decided to invent a new word, instead of using adjectives available in Latin like clarus or perspicuus. As we know, the term created is “evidencia” (Lévy and Pernot, 1997, p. 10), based on videre, to see. Ironically, Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca – who have renewed the field of argumentation by explicitly rejecting the Cartesian concept of “évidence” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1970, p. 4) – take for granted the argumentative value of presence as enargeia or evidencia!

The same holds true for another category of figures that, according to Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, plays an argumentative role: that of communion. Its purpose is to create or confirm communion with the audience. Again, this is a very persuasive means. Also, from these examples, it should be clear that, for Perelman, the argumentativity of figures corresponds to their persuasiveness. Furthermore, Charles Hill, in his essay on the psychology of rhetorical images, shows that “vividness is almost a direct synonym of visualization”, and that “vividness enhances persuasiveness”, so that “vividness, emotional response and persuasion have all been shown to correlate to each other” (Hill, 2004, p. 32). So, even if presence is one of the four major rhetorical qualities of images – and is therefore crucial for visual argumentation (Kjeldsen, 2012, p. 240) – one can still wonder whether it is argumentative or persuasive. The problem, here, arises from Perelman’s understanding of argument as aiming to provoke or increase the adherence of the audience. Yet such an understanding doesn’t make it easy to distinguish between argumentative means (i.e. giving reasons to support a point of view) and non-argumentative means. Indeed, not all means used to influence an audience can be considered as argumentative. For this reason, it seems to me that it is not enough for visual argumentation to rely on The New Rhetoric to found the argumentativity of figures.

2.2 Reboul and Bonhomme

The same position has been adopted by some of Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s followers. As is often the case, followers have a tendency to exaggerate when they adopt a systematic idea, i.e. in this case, considering that all the figures can be understood as argumentative. For example, in his book Introduction à la rhétorique, Olivier Reboul dedicates a chapter to the argumentative role that the figures of rhetoric may play. When Reboul writes about the “argumentative strength” of a figure, he is above all referring to its persuasive force. For him, a figure is rhetorical only “to the extent that it contributes to persuading” (Reboul 1991, p. 121). Hence the fact that his chapter includes figures – like rhythm – that are based on the sound of the words. This is not surprising, given his objective. As he puts it, “the rhythm produces a feeling of obviousness able to satisfy the mind, but also to enroll it” (Reboul 1991, p. 124). Indeed, how would it be possible to claim that all figures can be argumentative? Only from a broadened understanding of argumentation associated to persuasion, but also to pleasure. According to Reboul, Perelman’s theory on the relationship between figures and argumentation “is too intellectualist, too oblivious of the figure pleasure, a pleasure deriving either from emotion or from comic, but always from pathos” (Reboul, 1991, p. 122).

Another interesting case in point is found in Marc Bonhomme. At the end of his book Les figures clés du discours, a few pages are dedicated to “argumentation through figures”, in which he posits that besides their aesthetic function, figures also have “a practical end oriented toward the productivity of utterances. In this case, figures are seen as argumentation tools, influencing the opinions of their addressees and stimulating their adherence to the discourse that has been produced. More precisely, they work like persuasive speech acts playing with reasoning (to persuade), but above all on the affects (to hit)” (Bonhomme 1998, p. 88). Such an understanding is again very close to that of Perelman.

This same author developed this issue in a paper focused on the argumentativity of figures. In the introduction, he explains that, for him, there are three ways of understanding the relationship between rhetoric and argumentation. The first one is convergence: an argumentative discourse is considered to be rhetorical if its aim is to persuade. The second is differentiation: from this point of view, a discourse can be seen as rhetorical without being argumentative. And the third one is inclusion: in this case, argumentativity is only one amongst the different dimensions of a rhetoric discourse. As a rhetorician, Bonhomme adopts this third option. This explains why he distinguishes five functions in a rhetoric discourse: aesthetic, phatic, pathemic, cognitive, and finally argumentative. According to the definition he gives, a rhetoric discourse plays “an argumentative function when, through different factors […] the figures contribute to persuasion, acting on the addressee’s capacity to change their behavior. When it succeeds, such persuasion reinforces their beliefs and their convictions” (Bonhomme 2009, § 20).

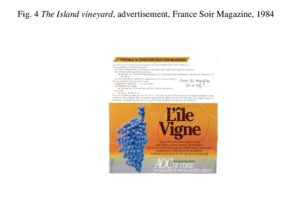

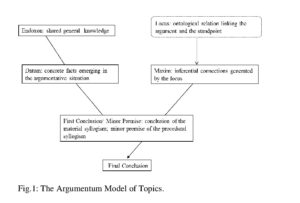

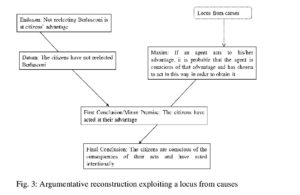

According to this understanding, argumentation is a province of rhetoric, and rhetoric is (again) reduced to persuasion. This, in turn, has consequences on the way Bonhomme conceives of the argumentativity of visual figures. For example, for him, metonymy works as a transfer from agent to product, matter to product, product to place, and so on. He explains: «These isotopic transfers make it possible for advertising to manipulate the universe of the products so as to make them desirable for the public and trigger the act of buying» (Bonhomme 2009, § 46). An example given by Bonhomme in another paper (Bonhomme, 2008, p. 221) is an ad for a Corsican wine, The Island vineyard (fig. 4).

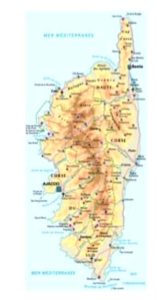

It relies upon the fact that the grapevine is shaped like the island of Corsica (fig. 5).

Hence Bonhomme’s analysis of the metonymy as a transfer from product to place. Here, it seems that this visual metonymy has a purely persuasive function, as it helps the consumer, at the moment of purchase

choice, to associate wine and Corsica. Even though it is important to show that some figures play an important persuasive role in images, visual rhetoric cannot be confused, however, with visual argumentation if we consider the latter as providing reasons to support a claim. (Fig. 5 Map of Corsica)

2.2.1 Metonymy

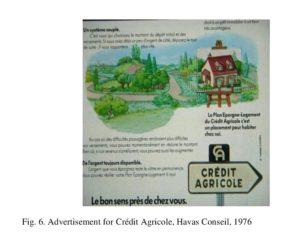

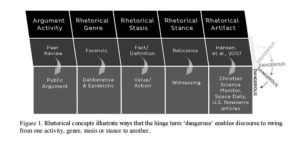

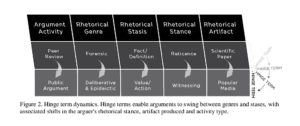

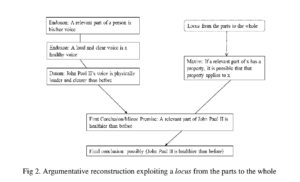

In fact, Bonhomme’s conception of the argumentativity of figures depends on his theoretical presuppositions, namely the rhetorical approach he applies to figures. But, besides this understanding of the rhetorical function of metonymy as persuasive, others interpretations are possible. For instance, Christian Plantin suggests that the mechanism that explains how metonymies work is like the mechanism that makes it possible to derive a conclusion from an argument. “In the metonymy of effect, the designation of the effect is replaced by that of the cause associated to it. In argumentation through consequences, the value judgment given to a consequence is transferred to its cause. The laws governing this kind of substitution of signifiers in a trope are not different from those that conclude to the acceptability of a cause from that of its effect (argument by consequences). We could therefore speak of a metonymic argumentation” (Plantin 2009, § 22). For sure, there are many images corresponding to this kind of metonymy of effects and causes. Let me examine one (Fig. 6).

I previously focused on this ad precisely because it recycles a series of paintings by Magritte (La Belle Captive) (Roque, 1983, p. 111-113). Here, I will analyze its argumentativity. So I’ll first describe the contents and context of the ad. It is taken from an ad campaign used by a French savings that focuses on housing. The text in bold just below the house reads: “The Crédit Agricole savings housing plan is an investment to live at home”. And below the road sign that points to the bank, there reads an inscription: “common sense close to your home,” which served as a slogan as well as an identification code for the bank in the eighties, across multiple ad campaigns.

This ad represents a case of a mixed media argument. According to a classification I proposed, it is what I call a joint argument, i.e. an argument produced by using visual as well as verbal elements (Roque, 2012, p. 283). It is also important to note that in a joint argument, both parts (verbal and visual) contribute to the argument. In this case, the text alone doesn’t advance all the reasons to open a savings account: the body text, printed in small letters, is a description of the savings program. The text below the picture of a house is also informative, explaining the purpose of the savings plan (to live in one’s own house). And finally, the text “Common sense close to your home” could serve as a conclusion to the argument (in addition to its role of reinforcing the bank’s brand), but not as the argument itself.

The image is based on a famous painting by Magritte that shows a canvas painting of a house that blends into the landscape in its background. The image relies upon a visual pun that pivots on the word “plan”, namely a savings plan and a house plan on paper. Rhetorically, it corresponds to a visual syllepsis, since the same graphic element can be perceived as being simultaneously part of two distinct sets (Noguez, 1974, p. 120). Now the house plan blends into the land where it is to be built. We could see it a metonymy of effect or otherwise of product and place. I have also suggested elsewhere (Roque, 2005, p. 275-276) that it could be understood as a particular case of metonymy, i.e. a metalepsis, since there is an inversion of cause (a savings plan) and consequence (building a house): in the image, the house is presented as having already been built.

The Magrittean image is quite effective, since it shows that the plan to have one’s own house is not just a dream but can easily become real thanks to Crédit Agricole’s savings plan. It is very persuasive, too: the house has a strong presence and helps suggest that it is easy to turn a dream into a house. If we consider the image as persuasive, it would be interesting to ponder whether it is also argumentative. But first of all, what is the visual argument here? We could say that it is something along the lines of: a saving account is a good investment because soon you’ll be the owner of your own home. Therefore a savings account is a common sense investment. The reference to the “common sense” is important as a way of suggesting that opening a savings plan is a rational and good decision. Furthermore, if one accepts that the visual might be dialogic (Roque, 2008), I would like to suggest that this is the case here: the visual part of the argument also seems to be a proleptic[iii] response to a possible objection about time: how many years would I have to save money before having my own house? Yet the image collapses the distance between cause and effect, project and realization. Therefore it helps to think that a savings plan is a good investment.

So how are we to analyze the visual rhetoric used in such an ad? As persuasive or as argumentative? The response is: both. The syllepsis can be considered as persuasive, as it suggests that the house simultaneously belongs to representation (painted on a canvas) and reality (built in the estate). As for the metonymy, it can be seen as persuasive, like Bonhomme does, if we understand the metonymy as a transfer through contiguity, between the product (a house to be built thanks to a savings plan) and the place (the private housing estate where the house has to be/is built). Conversely, we can see it as argumentative, like Plantin does, in so far as the acceptability of the consequence (to be landlord) is transferred to the cause (to buy a savings plan). Finally, the prolepsis, when it is used to anticipate a possible objection, is argumentative, too. The conclusion we can draw from it is that the same figure, in this case a trope (metonymy), can be understood either as persuasive or as argumentative. Therefore, these points of view are not exclusive. The fact that some visual figures are persuasive doesn’t prevent them from also being argumentative, at least in some cases. This first conclusion already has an important consequence: visual images cannot be easily rejected from the field of visual argumentation for being persuasive if we succeed in showing that they also work argumentatively.

3. Peersuasion and argumentation

In a previously published paper, I made the following argument: since a figure can be persuasive and argumentative at the same time, a distinction should be made between a strong and a weak notion of visual argumentation. I proposed to call a visual argumentation “strong” when an image is fully argumentative, i.e. when it gives reasons in order to support (or criticize) a point of view. Conversely, it should be qualified as “weak” when it is merely persuasive and influences the addressee (Roque 2011, p. 98-99). Such a suggestion doesn’t seem satisfying any longer. Why? Because it supposes that it would be possible to clearly distinguish which images would be “purely” persuasive and which are “purely” argumentative. In practice, such a distinction is challenging to apply. It turns out that persuasive and argumentative elements are often closely combined. The reason for distinguishing between strong and weak visual argumentation was to fortify visual argumentation as a well-founded field because it excluded visual persuasion from it. However, such a view also presupposes that persuasion is not rational. But there are indeed cases of rational persuasion, sometimes even ones that use emotional means of arousal (O’Keefe, 2012).

So, instead of separating persuasive and argumentative aspects, it is more convenient to accept that they often work together. This is, nevertheless, a controversial issue. Some authors hold that persuasion and argumentation should be carefully separated. My opinion is that in some cases – and visual argumentation is certainly one of them – persuasion and argumentation intersect and are intertwined (Nettel & Roque, 2012). This understanding corresponds to that held by informal logicians, like Ralph Johnson and Tony Blair, who claim that argumentation is rational persuasion (Johnson 2000, p. 149-150; Blair, 2012). Blair’s analysis of different types of advertising is a good case in point (Blair, 2012, p. 75-77). In some advertisements, there is a mix of rational and non-rational – or irrational – reasons given for preferring one brand over others. Yet, if “the argument is the effective persuasive tool […] persuasion occurs through the use of arguments” (Blair, 2012, p. 76) and we have a case of rational persuasion.

Now, once we stop considering persuasion and argumentation as mutually exclusive, it becomes essential, when analyzing images, to determine whether or not persuasion is accompanied by a set of rational reasons provided to support a claim. Indeed, adversaries of visual argumentation could claim that in such cases, even though it is true that there is persuasion as well as argumentation, the persuasive role would be that of images.

For this reason it is important to better understand the relationship between figures of rhetoric and argumentation. Two different kinds of relationship have been envisaged: either figures help better present arguments, or figures are arguments themselves (Reboul, 1986, p. 184; Bonhomme, 1998, p. 88; Tindale, 2004, p. 59). In the first case, the relationship between figure and argumentation is extrinsic. In the second, it is intrinsic. When the relationship is extrinsic, the figure cannot be considered properly “argumentative”; it remains exterior to the argument and is merely persuasive most of the time. In the second case, it must be recalled that when a figure itself is an argument, this doesn’t necessarily mean that it cannot also be persuasive. Yet, what happens for the general relationship between persuasion and argumentation holds true, too, for the figures.

As we already saw, a trope like metonymy can be simultaneously seen as persuasive and argumentative. So it turns out that it is hardly possible to separate persuasive and argumentative aspects of a given figure. Furthermore, the distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic relationship is itself relative. Indeed, at the end of his 1986 paper, Reboul considers that the two different cases, extrinsic and intrinsic “are almost always indistinguishable” (Reboul, 1986, p. 186). For this reason, he relinquished the distinction when reprinting his paper as a chapter of his book (Reboul, 1991).

4. Conclusion

1. By examining the relationship between figures of rhetoric and argumentation, it turns out that, for most authors, when a figure is used in discourse, its function is primarily persuasive. Consequently, we must be careful when transposing their idea to the field of visual argumentation, since images are generally considered as more persuasive than argumentative.

2. This is particularly true for what Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca call figures of “presence” (hypotyposis, energeia). The fact that they are effective and impress the audience doesn’t necessarily transform them into argumentative tools.

3. Some figures (like metonymy) appear to be considered as persuasive and also argumentative. Furthermore, it is hardly possible to separate figures that would be persuasive from figures that would be argumentative.

4. If we admit that persuasion and argumentation are very often combined, the fact that many images are persuasive doesn’t prevent them from being simultaneously argumentative (at least in some cases). This point is quite important to counter the argument according to which images would be mainly persuasive. However, this raises the need to distinguish between these two complementary functions of images.

5. The concept of strategic maneuvering can be helpful here because it “refers to the continual efforts made in all moves that are carried out in argumentation discourse to keep the balance between reasonableness and effectiveness” (van Eemeren, 2010, p. 40). Similarly, I would like to suggest that something similar occurs in visual images. When there is a balance between reasonableness and effectiveness, visual images can be considered as successfully displaying a visual argument. But when effectiveness (i.e. persuasiveness – even though van Eemeren warns us that effectiveness and persuasiveness are not completely synonymous: van Eemeren, 2010, p. 39) gets the better of reasonableness, visual images are mainly persuasive.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Marc Bonhomme for giving me a reproduction of fig. 4.

NOTES

i. I will leave aside the complex issue of the relationship between verbal rhetoric and visual rhetoric, i.e. examining to what extent the verbal rhetoric terms can be transposed into visual rhetoric.

ii. Both deal with rhetoric and visuality, and their names are very similar. However, « energeia, » usually translated as « activity, » means « vividness, » while « enargeia » has the general meaning of visual clarity, but also pictorial vividness. As it has been noted, Aristotle uses the first one in his Rhetoric, not the second one (Zanker 1981, note 40 p. 307).

iii. On the prolepsis as persuasive and argumentative, see Nettel and Roque, 2012, p. 64-65.

References

Adam, J.-M., & Bonhomme, M. (2005). L’Argumentation publicitaire. Rhétorique de l’éloge et de la persuasion. Paris: Armand Colin.

Anscombre, J.-C., & Ducrot, O. (1986). Argumentativité et informativité. In M. Meyer (Ed.), De la métaphysique à la rhétorique (pp. 79-94). Brussels: Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

Aristotle. (2005). Poetics and Rhetoric, Ed. E. Garver. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Belle, H. van (2009). Playing with Oppositions. Verbal and visual antithesis in the media. In J. Ritola (Ed.), Argument Cultures: Proceedings of OSSA 09, CD-ROM (pp. 1-13), Windsor, ON: OSSA.

Blair, T. (2004). The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments. In C. A. Hill and M. Helmers (Eds.), Defining Visual Rhetorics (pp. 41-61). Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Blair, T. (2012). Argumentation as Rational Persuasion. Argumentation 26-1, 71-81.

Bonhomme, M. (2009). De l’argumentativité des figures de rhétorique. Argumentation et analyse du discours, 2, special issue, Rhétorique et argumentation (http://aad.revues.org/index495.html).

Bonhomme, M. (1998). Les figures clés du discours. Paris: Seuil.

Bonhomme, M. (2008). Peut-on parler de métonymie iconique? In S. Badir & Klinkenberg, J.-M. (Eds.), Figures de la figure. Sémiotique et rhétorique générale (pp. 215-228). Limoges: Presses Universitaires de Limoges.

Doury, M. (2012). Preaching to the converted. Why Argue when Everyone Agrees. Argumentation 26-1, 99-114.

Ducrot, O. (1992). Argumentation et persuasion. In W. De Mulder, F. Schuerewegen & L. Tasmowski (Eds.), Énonciation et parti-pris: Actes du Colloque d’Anvers, février 1990 (pp. 143-158). Amsterdam & Atlanta: Rodopi Bv Editions.

Eemeren, Frans H. van. (2010). Strategic Maneuvering in Argumentative Discourse. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Fontanier, P. (1968). Les figures du discours. Paris: Flammarion.

Hill, Charles A. (2004). The Psychology of Rhetorical Images. In C. A. Hill and M. Helmers (Eds.), Defining Visual Rhetorics (pp. 25-40). Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Johnson, R. H. (2000). Manifest Rationality: A Pragmatic Theory of Argument. Mahwah, NJ/London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Jowett, G. S. & O’Donnell, V. (1992). Propaganda and Persuasion. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, Cal. & London: Sage.

Kjeldsen, J.E. (2012). Pictorial Argumentation in Advertising: Visual Tropes and Figures as a Way of Creating Visual Argumentation. In F. H. van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Topical Themes in Argumentation Theory. Twenty Exploratory Studies (pp. 239-255). Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London & New York: Springer.

Lévy, C. & Pernot, L. (1997). Phryné dévoilée. In C. Lévy & L. Pernod (Eds.), Dire l’évidence (Philosophie et rhétorique antiques) (pp. 5-12). Paris: L’Harmattan.

Messaris, P. (1997). Visual Persuasion. The Role of Images in Advertising. Thousands Oaks, Cal., London & New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Micheli, R. (2012). Arguing without Trying to Persuade? Elements for a Non-Persuasive Definition of Argumentation. Argumentation, 26-1, 115-126.

Nettel, A. L., & Roque, G. (2012). Persuasive Argumentation Versus Manipulation. Argumentation, 26-1, 55-69.

Noguez, D. (1974). Petite rhétorique de poche pour servir à la lecture des dessins dits “d’humour”. L’Art de masse n’existe pas. Special issue. Revue d’esthétique, 1974, 3/4, 107-137.

0’Keefe, D. (2012). Conviction, Persuasion and Argumentation: Untangling the Ends and Means of Influence. Argumentation, 26-1, 19-32.

Perelman, C. & Olbrechts-Tyteca L. (1970). Traité de l’argumentation: La Nouvelle Rhétorique. Brussels: Editions de l’Institut de Sociologie, Université Libre de Bruxelles.

Plantin, C. (1990). Essais sur l’argumentation. Introduction à l’étude linguistique de la parole argumentative. Paris: Kimé.

Plantin, Christian. 2009. Un lieu pour les figures dans la théorie de l’argumentation. In Argumentation et analyse du discours 2. http://aad.revues.org/215. Accessed 23 July 2011.

Plantin, C. (2012). Persuasion or Alignment? Argumentation, 26-1, 83-97.

Pratkanis, A., & Elliot Aronson E. (2001). Art of Propaganda: The Everyday Use and Abuse of Persuasion. New York: W.H. Freeman & Company.

Reboul, O. (1986). La figure et l’argument. In M. Meyer (Ed.), De la métaphysique à la rhétorique (pp. 175-187). Brussels: Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

Reboul, O. (1991). Introduction à la rhétorique: Théorie et pratique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Roque, G. (1983). Ceci n’est pas un Magritte. Essai sur Magritte et la publicité. Paris: Flammarion.

Roque, G. (2005). Sous le signe de Magritte. In J. Pier & J.-M. Schaeffer (Eds.), Métalepses. Entorses au pacte de la représentation (pp. 263-276). Paris: Editions de l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences sociales.

Roque, G. (2008). Political Rhetoric in Visual Images. In E. Weigand (Ed.), Dialogue and Rhetoric (pp. 185-193). Amsterdam/Philadelphy: John Benjamins Publishing Company,

Roque, G. (2011). Rhétorique visuelle et argumentation visuelle. Semen 32, 91-106.

Roque, G. (2012). Visual Argumentation: A Further Reappraisal. In F. H. van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Topical Themes in Argumentation Theory. Twenty Exploratory Studies (pp. 273-288). Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London & New York: Springer.

Scott L. M., & Batra R., (Eds.) (2003). Persuasive Imagery: A Consumer Response Perspective. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Seidman, S. A. (2008). Posters, Propanganda and Persuasion in Election Campaigns around the World and through History. New York: Peter Lang.

Spangeburg, R., & Moser K. (2002). Propaganda. Understanding the Power of Persuasion. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers, Inc.

Vouilloux, B. (1995). Des deux statuts rhétoriques de l’image et peut-être d’un troisième. In L.H. Hoek & K. Meerhoff (Eds.), Rhétorique et image. Textes en hommage à Á. Kibédi Varga (pp. 101-114). Amsterdam & Atlanta: Rodopi.

Zanker, G. (1981). Enargeia in the Ancient Criticism of Poetry. Rheinisches Museum fur Philologie 124, 297-311.